The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals was asked today to order the operator of the Birmingham City bus line…

Press Release

April 28, 1960

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals was asked today to order the operator of the Birmingham City bus line…, 1960. bb2a569f-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74741fe3-8b1c-4975-bf0b-0a22830e6cfc/the-fifth-circuit-court-of-appeals-was-asked-today-to-order-the-operator-of-the-birmingham-city-bus-line. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

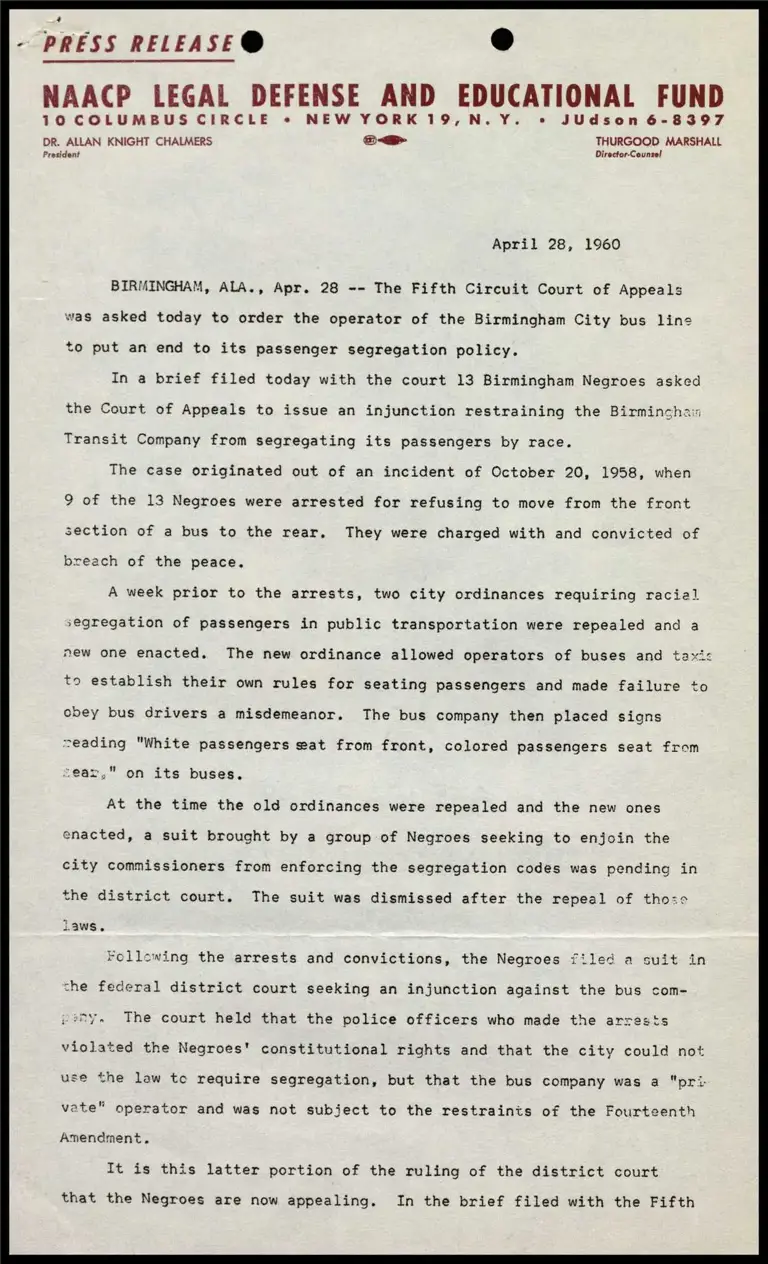

- PRESS RELEASE® ®

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS o> THURGOOD MARSHALL

Director-Counsel President

April 28, 1960

BIRMINGHAM, ALA., Apr. 28 -- The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals

was asked today to order the operator of the Birmingham City bus line

to put an end to its passenger segregation policy.

In a brief filed today with the court 13 Birmingham Negroes asked

the Court of Appeals to issue an injunction restraining the Birminchain

Transit Company from segregating its passengers by race.

The case originated out of an incident of October 20, 1958, when

9 of the 13 Negroes were arrested for refusing to move from the front

section of a bus to the rear, They were charged with and convicted of

breach of the peace.

A week prior to the arrests, two city ordinances requiring racial

segregation of passengers in public transportation were repealed and a

new one enacted. The new ordinance allowed operators of buses and taxic

to establish their own rules for seating passengers and made failure to

obey bus drivers a misdemeanor. The bus company then placed signs

seading "White passengers eat from front, colored passengers seat from

“ear,” on its buses.

At the time the old ordinances were repealed and the new ones

enacted, a suit brought by a group of Negroes seeking to enjoin the

city commissioners from enforcing the segregation codes was pending in

the district court. The suit was dismissed after the repeal of tho:ze

laws.

Follcwing the arrests and convictions, the Negroes filed a suit in

che federal district court seeking an injunction against the bus com-

any. The court held that the police officers who made the arrests

violated the Negroes’ constitutional rights and that the city could not

use the law te require segregation, but that the bus company was a "pri

vate" operator and was not subject to the restraints of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

It is this latter portion of the ruling of the district court

that the Negroes are now appealing. In the brief filed with the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals their attorneys argue that the district court

erred in denying the injunction against the bus company which continues

to require Negroes to ride in the back of its buses.

Attorneys representing the 13 Negroes are Thurgood Marshall, Ja

Greenberg and James M. Nabrit, III of the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund staff in New York City, and Arthur D. Shores of

Birmingham, Ala.

=n30e-