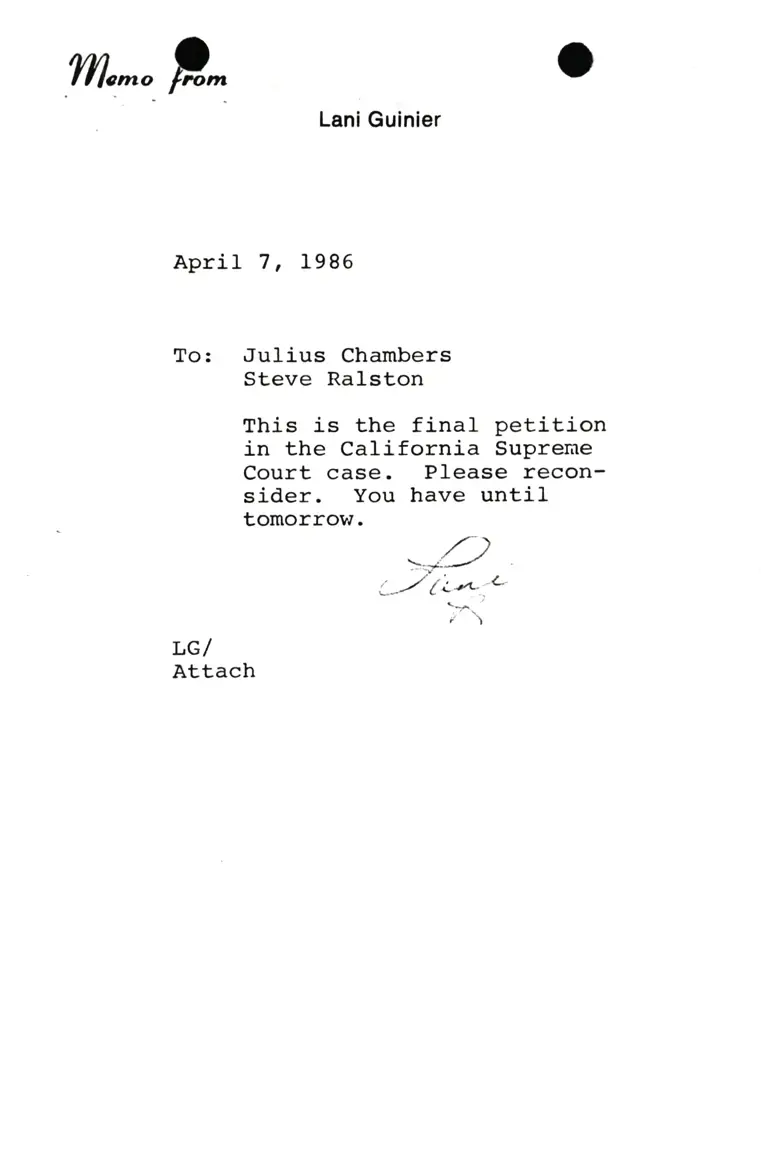

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Julius Chambers and Steve Ralston

Correspondence

April 7, 1986

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Julius Chambers and Steve Ralston, 1986. b16d55e8-e992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7484c84d-3569-42b4-8ab4-2cf363a917d5/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-julius-chambers-and-steve-ralston. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

//l",no Q^

Lani Gulnler

April 7, 1986

To: Julius Chambers

Steve Ralston

This is the final petition

in the California Supreme

Court case. Please recon-

sider. You have until

tomorrow.

=*CL-/ (;-+:L

'*r

LG/

Attach