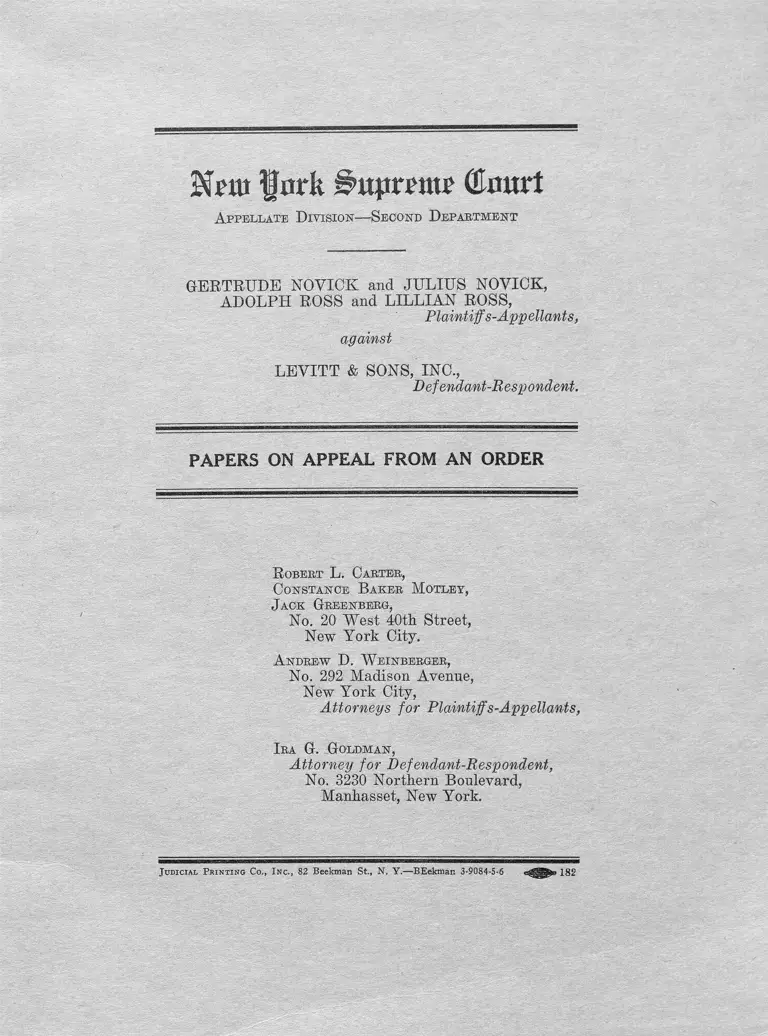

Novick v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. Papers on Appeal from an Order

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Novick v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. Papers on Appeal from an Order, 1951. 301ccc0e-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74b3aa7e-63cb-4b57-b975-33a3705c7780/novick-v-levitt-sons-inc-papers-on-appeal-from-an-order. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

Jfatu |jork Glmtrt

A ppellate D ivision— S econd D epartm e n t

GERTRUDE NOVIOK and JULIUS NOVICK,

ADOLPH ROSS and LILLIAN ROSS,

Plaintiffs-App ellants,

against

LEVITT & SONS, INC.,

Defendant-Respondent.

PAPERS ON APPEAL FROM AN ORDER

R obert L. Carter,

C onstance B ak er M otley,

J ack G reenberg,

No. 20 West 40th Street,

New York City.

A ndrew D. W einberger,

No. 292 Madison Avenue,

New York City,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants,

I ra G. G oldm an ,

Attorney for Defendant-Respondent,

No. 3230 Northern Boulevard,

Manhasset, New York.

J u dic ia l P r in t in g Co., I n c ., 82 Beekman St., N. Y.—BEekman 3-9084-5-6 ggggjifep 182

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement Under Rule 234 ................................ 1

Notice of A ppea l................................................. 2

Order Appealed F ro m ................................ 3

Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J.................... 28

Stipulation Waiving Certification................... 33

P apers R ead in S upport of M otion

Notice of Motion .......................................... 5

Summons .......................................................... 6

Complaint ......................................................... 7

Exhibit A—Letter from Bethpage Realty

Company to Tenants, dated March 15,

1949 ........................................................... 17

Exhibit B—Copy of lease........................... 18

Exhibit C—Copy of amendment to the

Administrative Rules of the Federal

Housing Commission under Title VII

of the National Housing A c t ............... 26

Exhibit D—Letter, dated August 3, 1950,

from Levitt and Sons to Mrs. Ger

trude N ovick............................................ 27

1

Km fork i>uprrmp Olourt

A ppellate D ivision— S econd D epartm ent

G ertrude N ovick and J u l iu s N ovick , A dolph

R oss and L illian R oss,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

against

L evitt & S ons, I n c .,

, Defendant-Respondent.

Statement Under Rule 234

This is an appeal by the plaintiffs herein from

an order of Special Term Part II of the Supreme

Court, Nassau County (Cuff, J.) made and en

tered in the office of the Clerk of the County of

Nassau on March 1, 1951 granting defendant’s

motion to dismiss the complaint for failure to

state facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action.

This action was commenced by the service of a

summons and verified complaint on November 30,

1950.

Notice of Appeal was served March 12, 1951.

The plaintiffs are represented by Robert L.

Carter, Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley

and Andrew D. Weinberger as their attorneys.

Defendant appeared by Ira G. Goldman.

There has been no change of parties or at

torneys.

2

4 Notice of Appeal

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF

NEW YORK

C o u n t y of N assau

5

6

--— — —— - .....

Gertrude N ovice and J u liu s N ovice, A dolph

R oss and L il l ia n R oss,

Plaintiffs,

again st

L evitt & S ons, I n c .,

Defendant.

P lease take notice that the plaintiffs herein

hereby appeal to the Appellate Division of the

Supreme Court, Second Department, from the

order made in the above entitled action and en

tered in the Office of the Clerk of the County of

Nassau on the 1st day of March, 1951, which

granted in all respects defendant’s motion to dis

miss the complaint and which dismissed the com

plaint for the reason that it fails to state facts

sufficient to constitute a cause of action, and this

appeal is taken from the whole and from each

and every part of said order.

Dated: March 12, 1951

C onstance B aker M otley

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

A ndrew D. W einberger

292 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

3

Order Appealed From 7

To:

I ka G. G oldm an , Esq.

3230 Northern Boulevard

Manhasset, New York

Cleek of t h e C o u n ty of N assau

Order Appealed From

At a Special Term Part II of the Su- g

preme Court held in and for the

County of Nassau at the Nassau

County Courthouse, Old Country

Road, Mineola, N. Y., on the 1st day

of March, 1951.

Present:

Honorable T h om as J. Cu f f ,

Justice.

[S a m e T it l e ]

The defendant having moved this Court for 9

judgment pursuant to Rule 106 of the Rules of

Civil Practice, dismissing the complaint upon the

ground that upon the face thereof it does not state

facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action;

and the motion having duly come on to be argued

before me on January 10, 1951; and after hear

ing Ira G. Goldman, Esq., attorney for the de

fendant, by John F. Havens, Esq., of counsel, in

support of the motion, and Andrew D. Wein

berger, Esq., one of the attorneys for the plain

tiffs, in opposition thereto; and due deliberation

having been had and the decision of the Court

4

dated February 21, 1951 having been duly filed

herein;

Now upon reading and filing the notice of this

motion, dated the 15th day of December, 1950, to

gether with proof of due service thereof, the sum

mons and complaint verified November 29, 1950,

and the Exhibits A, B, C and D annexed thereto

and the memoranda of the defendant, in support

of the motion; and the memorandum of the plain

tiffs in opposition thereto;

11 It is upon motion of Ira G. Goldman, Esq.,

attorney for the defendant, hereby

O rdered that the m otion be and the sam e hereby

is in a ll resp ects g ra n ted and that the com pla in t

h erein be and the sam e h ereb y is d ism issed fo r

the reason that it fa ils to state fa c ts sufficient to

constitu te a cause o f a ction togeth er w ith costs

and $10 m otion costs to the defen dan t.

Enter.

T homas J. C u ff

12 J. S. C.

Granted

Mar.—1, 1951

Chas. E. R ansom

Clerk

Entered

Mar. 1, 1951

Chas. E. R ansom

County Clerk of Nassau County

XO Order Appealed From

5

Notice of Motion

SUPREME COURT

N assau C o u nty

[S ame T itus]

Silts:

P lease take notice that upon the complaint

herein, verified November 29, 1950, the under

signed will move this Court at a Special Term

Part II to be held in and for the County of Nassau

at the Nassau County Courthouse, Old Country

Road, Mineola, New York, on the 27th day of

December, 1950, at 10 o ’clock A. M. or as soon

thereafter as counsel can be heard, for judgment

pursuant to Rule 106 of the Rules of Civil Prac

tice, dismissing the complaint upon the ground

that upon the face thereof it does not state facts

sufficient to constitute a cause of action and grant

ing to the defendant such other and further relief

as to the Court may seem just and proper.

Dated: December 15, 1950.

I ra G. G oldman

Attorney for Defendant

Office and Post Office Address

3230 Northern Boulevard

Manhasset, New York

To:

R obert L. Carter, Esq.,

J ack G reenberg, Esq.,

C onstance B aker M otley , Esq., and

A ndrew D. W einberger, Esq.,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF

NEW YORK

C o u nty op N assau

Plaintiffs designate Nassau County as the place

of trial.

Summons, Read in Support of Motion

G ertrude N ovick and Junius N ovick , A dolph

Ross and L illian R oss,

Plaintiffs,

against

L evitt & S ons, I n c .,

Defendant.

Plaintiffs resides in Nassau County.

To the above named Defendant:

You are hereby sum m oned to answer the com

plaint in this action, and to serve a copy of your

answer, or, if the complaint is not served with

this summons, to serve a notice of appearance,

on the Plaintiff’s Attorney within twenty days

after the service of this summons, exclusive of the

day of service; and in case of your failure to ap

pear, or answer, judgment will be taken against

7

you by default, for the relief demanded in the

complaint.

Dated, November 29,1950

R obert L. Carter

J ack G reenberg

C onstance B aker . M otley

Attorneys for Plaintiff

Office and Post Office Address

20 West 40th Street 20

New York 18, N. Y.

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion 39

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion

SUPREME COURT OP THE STATE OF

NEW YORK

C o u n ty of N assau

[S a m e T it l e ]

Plaintiffs complaining of the defendant by

Robert L. Carter, Jack Greenberg, Constance

Baker Motley, and Andrew D. Weinberger, their

attorneys, respectfully allege and show to this

court as follows:

I. That the plaintiffs, Gertrude and Julius

Novick, man and wife and the parents of two

minor children, presently reside and at all times

hereinafter mentioned resided in Levittown,

County of Nassau, State of New York.

II. That the plaintiffs, Adolph Boss, a veteran

of World War II, and Lillian Ross, man and wife

and the parents of two minor children, presently

reside and at all times hereinafter mentioned

resided in Levittown, County of Nassau, State of

New York.

III. That the defendant, Levitt and Sons, Inc.,

is a New York corporation incorporated under

the laws of the State of New York with principal

offices in Manhasset, Nassau County, New York.

IV. That the said defendant is engaged in the

business of constructing homes and has con

structed a community of homes known as Levit

town, situated in Nassau and Suffolk Counties in

the State of New York; and that said community

consists of approximately 10,000 small homes, ap

proximately 1,500 of which have been leased by

defendant for dwelling purposes and the remain

ing number sold by defendant for the same pur

pose.

V. That said community of homes was built with

the aid of the federal government through the

Federal Housing Administration which insured,

pursuant to the provisions of Title 12, IJ. S. Code,

Sec. 1707 et seq., all of the mortgages on said

homes, which were secured from various mort

gagees by defendants and others as mortgagors,

conforming to various requirements of the Fed

eral Housing Administration as to such matters

Complaint, Bead in Support of Motion

9

as ultimate sole price, size, quality of building

materials, site, location, probable resale ability

and value, etc.

VI. That defendant without said aid from the

federal government would not have been able to

construct the community of homes known as Levit-

town on the large scale on which it has been con

structed.

VII. That the plaintiffs, Gertrude and Julius

Novick and Adolph and Lillian Ross, are the

lessees of two of said homes in Levittown which

are owned by the defendant and leased from de

fendant and known as 50 Honeysuckle Road and

52 Honeysuckle Road, Levittown, New York, re

spectively.

VIII. That plaintiffs, Gertrude and Julius No

vick, leased their premises from defendant on

December 22, 1949.

IX. That plaintiffs, Adolph and Lillian Ross, first

leased their premises from defendant on Novem- 2*3

ber 15, 1947, and last renewed said lease on De

cember 1, 1949.

X. That the said leases are presently in force

and presently binding upon both lessor and lessees

but, by their own terms, expire November 30,

1950.

XI. That neither the defendant lessor nor the

plaintiff lessees have breached any of the provi

sions of said leases.

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion 25

10

28 Complaint, Read in Support of Motion

XII. That it is the policy, custom, and practice of

the defendant as lessor, just prior to the expira

tion date of a lease, to send to each lessee a letter

and two copies of a new lease to he signed by the

lessee and returned to the defendant lessor in ac

cordance with said letter, a copy of which is at

tached hereto and marked Exhibit A. These let

ters usually provide as follows:

“ The efficient and economical manage

ment of huge rental project like Levit-

29 town necessitates our knowing in advance

whether you wish to renew your lease. If

you do, you must sign and return both

copies of the enclosed lease within two

weeks. Otherwise, we shall conclude that

you do not desire a renewal. This will re

quire your moving out when your present

lease expires.

“ This renewal is not effective unless and

until we send back to you one copy of the

lease signed by us.”

30

XIII. That unless the lessee breaches some pro

vision of the lease itself and is so notified by de

fendant, leases are always renewed in the man

ner indicated by said letter.

XIV. That in the past the leases of the plaintiffs,

Adolph and Lillian Ross, have been thus re

newed.

XV. That in the past the leases given by the

defendant and its subsidiaries, the Bethpage

Realty Corporation, and the Island Trees Realty

11

Corporation, domestic corporations, to their vari

ous lessees contained a provision which stated as

follows:

“ 24. T h e T e n a n t agrees n o t t o perm it

THE PREMISES TO RE! USED! OR OCCUPIED BY ANY

PERSON OTHER THAN MEMBERS OF THE CAU

CASIAN RACE BUT1 THE EMPLOYMENT AND1 MAIN

TENANCE OF OTHER THAN CAUCASIAN DOMESTIC

SERVANTS SHALL BE PERMITTED. ’ ’

A copy of said lease is attached hereto and 32

marked Exhibit B.

XVI. That when a lessee objected to this provi

sion in the lease, the defendant would, upon the

expiration of such lease, refuse to renew.

XVII. That the Federal Housing Administration,

approximately in June of 1949, compelled the de

fendant to remove such provision from all of its

leases.

XVIII. That the defendant removed said provi- 33

sion as a result of such compulsion but has con

tinued to enforce said provision and is presently

enforcing such provision in fact against these

plaintiffs who have permitted their premises to be

used by persons other than Caucasians.

XIX. That the rules and regulations of the Fed

eral Housing Administration were amended, effec

tive February 15, 1950, to provide that no mort

gage insurance shall be granted by the Federal

Housing Administration where any racial restric

tive covenant, such as that previously appearing

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion 31

12

34 Complaint, Bead in Support of Motion

in defendant’s leases, appear in deeds to or mort

gages on any properties sought to be insured. A

copy of the amendment is attached hereto and

marked Exhibit C.

XX. That this amendment was made in order to

bring the policies and practices of the Federal

Housing Administration in line with the Supreme

Court decisions in the Restrictive Covenant cases,

Shelley v. Kramer, Sipes v. McGhee, 334 IT. S. 1,

92 L. ed. 1161 (1948); Hurd v. Hodge, Urciolo v.

Hodge, 334 IT. S. 24, 92 L. ed. 1187 (1948), wherein

the United States Supreme Court held that a

party to a private restrictive covenant restricting

sale of private property to Caucasians may not

invoke the jurisdiction of any court, whether state

or federal, to enforce such an agreement.

XXI. That in July, 1950, plaintiffs Gertrude No-

vick and Lillian Ross invited certain Negro chil

dren, who are the children of some of their per

sonal friends, to play with their own children two

or three times a week on their lawns adjoining

their said leased premises.

XXII. That on August 3, 1950, the defendant

herein wrote a letter to Gertrude Novick and

Adolph Ross, a copy of which is attached hereto

and marked Exhibit D, notifying them that their

leases to the above-described premises expire on

November 30, 1950, and that they would be re

quired to vacate the premises on or before that

date and that upon their failure to do so, legal

proceedings would be immediately instituted to

remove them forthwith.

13

XXIII That tlie usual letter referred to above,

which is sent to defendant’s lessees just prior to

the expiration date of their leases, was not sent

to any of the plaintiffs and no reason was given

the plaintiffs by the defendant for refusing and

failing to renew their leases.

XXIV. That the plaintiffs attempted to inquire

of the defendant whether the defendant intended

to renew their leases but the defendant failed and

refused to reply. 38

XXV. That the plaintiffs never received any

complaint from the defendant with respect to the

manner in which they were carrying out the pro

visions and obligations of their leases.

XXVI. That on information and belief, the de

fendant has refused to renew the leases of the

plaintiffs for the reason that the said Gertrude

Novick and Lillian Ross invited the children of

their Negro friends to play with their children on

the defendant’s premises, which the plaintiffs

have leased, contrary to the policies of defendant, 39

formerly expressed in leases given by defendant

to its lessees and now enforced by defendant in

fact.

XXVII. That the defendant has an announced

policy of refusing to lease or sell property in

Levittown to Negroes contrary to the meaning

and intent of the amended rules of the Federal

Housing Authority referred to above.

XXVIII. That the defendant by enforcing as a

matter of fact the race restrictive covenant provi-

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion 3<

sion of its leases, which it was compelled by the

Federal Housing Authority to remove, is con

trolling its lessees in the choice of their guests

and is attempting to so control the plaintiffs con

trary to the laws and public policy of this state.

XXIX. That if the defendant successfully in

vokes the aid of a court of this state to evict the

plaintiffs, as defendant has threatened to do in its

letter to the plaintiffs, because defendant disap

proves of the race and color of the plaintiffs’

guests, such aid on the part of any court of this

state would he contrary to the public policy of this

state, the prohibition of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Federal Constitution, and the holding,

spirit, and intent of the Restrictive Covenant

cases cited above.

XXX. That the plaintiffs have no adequate rem

edy at law and will suffer irreparable harm unless

this court declares the rights and legal relations

of the parties and enjoins the defendant from

carrying out its threat to invoke the aid of a court

to evict the plaintiffs.

XXXI. That by reason of defendant’s refusal to

renew the leases of the plaintiffs, the plaintiffs

are in constant jeopardy of being evicted as hold

over tenants as threatened by defendant.

XXXII. That such eviction proceedings as threat

ened by defendant against plaintiffs would be

wholly without merit and contrary to the laws and

public policy of this state and should be so de

clared and enjoined.

Complaint, Read in Support of Motion

XXXIII. That unless this court enjoins the de

fendant during the pendency of this action and

until a final judgment in this cause is rendered

by this court from proceedings to invoke the juris

diction of any court in this state, the plaintiffs

will suffer irreparable injury and damage and are

without any other remedy at law.

XXXIY. That the plaintiffs are entitled to an in

junction restraining the defendant from invoking

the jurisdiction of any court in this state for the

purpose of assisting the defendant in evicting the

plaintiffs because the defendant disapproves of

the race, creed, color or national origin of the

plaintiffs’ guests.

W herefore, plaintiffs pray that this Court issue

a temporary injunction restraining the defendant

from proceeding to invoke the jurisdiction of any

court in this state to evict the plaintiffs at any

time during the pendency of this action and re

straining the defendant from proceeding with

such eviction proceedings until this court has ren

dered a final judgment in this case.

A n d wherefore, p la in tiffs p ra y f o r a ju d gm en t o f

this cou rt d e c la r in g :

1. That the defendant may not seek the aid of

any court in this state to evict the plaintiffs

from the premises leased to them by the de

fendant for the reason that the defendant

disapproves of the race, creed, color or na

tional origin of the plaintiffs’ guests.

2. That the plaintiffs have a right to have in

their home as guests of themselves or of

Complaint, Bead in Support of Motion

16

their children any persons whom they may

choose, regardless of their race, creed, color

or national origin, and the defendant as

lessor may not, consistent with the laws and

public policy of this state, seek to control

this choice in this respect.

3. That the public policy of this state would

prohibit the defendant from seeking the aid

of any court in this state to evict the plain

tiffs because the defendant disapproves of

^ the race, creed, color or national origin of

the plaintiffs’ guests.

4. That the Fourteenth Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution prohibits the courts of this

state, as well as any agency or subdivision

thereof, from giving aid to the defendant in

evicting the plaintiffs because the defendant

disapproves of the race, creed, color or na

tional origin of the plaintiffs’ guests or be

cause the plaintiffs have violated the defend

ant’s policy of restricting the use of its

48 premises to members of the Caucasian race.

5. That an injunction shall issue restraining

the defendant from invoking the jurisdiction

of any court in this state for the purpose of

assisting the defendant in evicting the plain

tiffs because the defendant disapproves of

the race, creed, color or national origin of

the plaintiffs’ guests or because the plain

tiffs have violated the defendant’s policy of

restricting the use of its premises to mem

bers of the Caucasian race.

46 Complaint, Read in Support of Motion

17

6. For such, other, further, or additional relief

as to this Court may appear just and proper.

R obert L. Carter

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

J ack G reenberg

20 West 40th Street

New York 18, New York

C onstance B ak er H otkey

20 West 40th Street 50

New York 18, New York

A ndrew D . W einberger

292 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

(Verified by Plaintiffs on November 29, 1950.)

Exhibit “A ” , Annexed to the Complaint

[Letterhead of]

BETHPAGE REALTY CORP.

March 15, 1949 51

The efficient and economical management of a

huge rental project like Levittown necessitates

our knowing in advance whether you wish to

renew your lease. I f you do, you must sign and

return both copies of the enclosed lease within

two weeks. Otherwise we shall conclude that you

do not desire a renewal. This will require your

moving out when your present lease expires.

This renewal is not effective unless and until

we send back to you one copy of the lease signed

by us.

Exhibit “ A ” , Annexed to the Complaint 49

B ethpage R ealty C obp.

18

BETHPAGE— RENEWAL 1

B e t h p a g e R e a l t y Corp., of 3230 Northern

Boulevard, Manhasset, New York, hereby leases

to

Exhibit “ B” , Annexed to the Complaint

for one year beginning

May 1, 1949

53 the premises described above, upon the following

conditions and covenants:

1. The Tenant agrees to pay rent at the annual

rate of $780.00 payable $65.00 monthly in advance

on the first day of each month.

2. The Tenant agrees to take good care of the

premises and of the household equipment fur

nished therewith, and forthwith at the Tenant’s

expense to make all repairs thereto not neces

sitated by the Landlord’s fault, except that the

54 Landlord, at its expense, will make all major struc

tural repairs to the premises not necessitated by

the Tenant’s fault or that of the Tenant’s family,

employees, invitees or licensees. The Tenant

agrees to deliver up the premises and equipment

in good condition at the expiration of the term.

3. The Tenant agrees not to assign this lease or

underlet the premises or any part thereof.

4. The Tenant agrees to allow the Landlord to

enter the premises at all reasonable hours to ex

amine the same or make repairs.

5. The Tenant agrees that the Landlord shall be

exempt from liability for any damage or injury

to person or property except such as may be

caused by its negligence.

6. The Tenant agrees that this lease shall be

subordinate to any mortgages now or hereafter

on the premises.

7. The Tenant agrees to comply with all of the

statutes, ordinances, rules, orders, regulations

and requirements of the Federal, State and Mu

nicipal governments, departments and bureaus,

applicable to the premises.

8. The Tenant agrees not to do, bring or keep or

to permit to be done, brought or kept on the prem

ises anything which will in any way increase the

fire insurance premium rate thereon.

9. T h e , S u m oe $100.00, H eretofore D eposited

B y th e T e n a n t W it h th e , L andlord as S ecurity

for th e P erform ance of a P rior L ease, S h a l l B e

R eturned W ith o u t I nterest to th e , T en an t

A fter th e , E xpiration of th e T erm : H ere in , P ro

vided th e T e n an t H as F u l l y P erformed. T he

T en an t A grees N ot to A ssign or E n cu m ber th e

S ecu rity .

10. The Tenant agrees that the failure of the

Landlord to insist upon a strict performance of

any of the conditions and covenants herein shall

not be deemed a waiver of any rights or remedies

that the Landlord may have, and shall not be

deemed a waiver of any subsequent breach or de-

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

fault in the conditions and covenants herein con

tained. This instrument may not be changed,

modified or discharged orally.

11. The Tenant agrees that should the premises

or any part thereof be condemned for public use,

this lease, at the option of the Landlord, shall be

come null and void upon the date of taking, and

rent shall be apportioned as of such date. No

part of any award, however, shall belong to the

Tenant.

12. The Tenant agrees that if, upon the expira

tion of the term, the Tenant fails to remove any

property belonging to the Tenant, such property

shall be deemed abandoned by the Tenant and

shall become the property of the Landlord.

13. The Tenant agrees thafithe obligation of the

Tenant to pay rent and perform all of the other

conditions and covenants hereof shall not be

affected by the Landlord’s inability, because of

circumstances beyond its control, to supply any

service or to make any repairs or to supply any

equipment or fixtures.

14. The Tenant agrees to employ and pay the

garbage and rubbish collector designated by the

Landlord, in default of which the Landlord may

make such payment and charge the same to the

Tenant as additional rent.

15. The Tenant agrees that the premises are

being rented “ as is” and that the Landlord shall

not be obligated to make any alterations, improve

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

ments or renovations therein, nor any repairs

other than those expressly provided for herein.

16. T h e T en an t A grees to A ssume th e R espon

sibility of E nsu rin g T h a t N o P erson S hall

W alk and N o th in g S h a ll B e P laced U pon th e

U n fin ish ed S ection of th e A ttic F loor, and T h a t

in th e E vent T h is C ondition I s V iolated and

D am age R esults to S u c h A ttic F loor and/ or to

t h e Ceilin g B elow , t h e T e n an t W il l P ay U pon

D em an d as A dditional R en t th e . C ost of R epairs

W h ic h A re E stimated at a M in im u m of $60.00.

17. The Tenant agrees that the Landlord assumes

no obligation for the servicing or repair of the

oil burner, washing machine, cooking stove, re

frigerator, or ventilating fan installed in the

premises. Solely for the convenience of the Ten

ant, the Landlord has arranged with Meenan, Oil

Company, Inc. to service the oil burner without

charge to the Tenant if and so long as the Ten

ant purchases fuel oil from that company.

18. The Tenant agrees not to erect or permit to be

erected any fence, either fabricated or growing,

upon any part of the premises.

19. The Tenant agrees not to keep or permit to be

kept any animals, pigeons or fowl upon the prem

ises except not more than two domestic animal

pets.

20. The Tenant agrees not to install or permit to

be installed any laundry poles or lines outside of

the house, except that one portable revolving

laundry dryer, not more than seven feet high, may

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

be used in the rear yard on days other than Satur

days, Sundays and legal holidays, provided that

such dryer shall be removed from the outside

when not in actual use on such permitted days.

21. The Tenant agrees not to place or permit to

be placed any garbage or rubbish outside of the

house except in a closed metal receptacle located

to the rear of the kitchen door and not more than

one foot from the exterior of the house and ex

cept when placed at the curbline before removal

in accordance with the regulations of the collecting

agency.

22. T h e T en an t A grees N ot to R u n or P ark or

P erm it to B e R u n or P arked A n y M otor V ehicle

U pon A n y P art of t h e P rem ises .

23. T h e T e n a n t A grees to C u t or Cause to B e

Cu t t h e L a w n and R emove or Cause to B e R e

moved T all Grow ing W eeds at L east O nce a

W eek B etw een A pril F ifte e n th and N ovember

F ifteen th . U pon t h e T e n a n t ’s F ailu re the

L andlord M ay D o S o and C harge th e C ost

T hereof to th e T e n a n t as A dditional R e n t .

24. T h e T e n a n t A grees N ot to P e r m it th e

P remises to B e U sed or O ccupied B y A n y P erson

O th er T h a n M em bers op the C aucasian R ace

B u t t h e E m plo ym en t and M ain ten an ce of O th er

T h a n Caucasian D omestic S ervants S h a ll B e

P erm itted .

25. The Tenant agrees not to place or permit to

be placed upon the premises any sign whatsoever

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

except a family or professional name or address

plate whose size, style and location are first ap

proved in writing by the Landlord.

26. The Tenant agrees not to use or permit the

premises to be used for any purpose other than

as a private one-family dwelling for the tenant

and the tenant’s immediate family or as a profes

sional office of a physician or dentist resident

therein.

27. The Tenant agrees not to erect or permit to

be erected on the premises any building or struc

ture, or to make or permit to be made any altera

tions or additions to the premises, or paint or

permit to be painted the exterior of the house

other than in the original colors, unless appro

priate plans, specifications and/or colors are first

approved in writing by the landlord.

28. The Tenant agrees not to do or permit to be

done on the premises anything of a disreputable

nature, or constituting a nuisance, or tending to

impair the condition or appearance of the prem

ises, or tending to interfere unreasonably with

the use and enjoyment of other premises by other

Tenants in Levittown.

29. The Tenant agrees that, if default be made in

the performance of any of the conditions or cove

nants herein, or if the premises shall become

vacant, or if the Tenant shall file a petition in

bankruptcy or be adjudicated a bankrupt or make

an assignment for the benefit of creditors, the

Landlord may (A) re-enter the premises by force,

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

24

summary proceedings or otherwise, and remove

all persons therefrom, without being liable to

prosecution therefor, and the Tenant hereby ex

pressly waives the service of any notice in writing

of intention to re-enter, or (B) terminate this

lease on giving to the Tenant 5 days’ notice in

writing of its intention so to do, and this lease

shall expire on the date fixed for the expiration

hereof. Such notice may be given by mail to the

Tenant addressed to the premises. The Tenant

agrees, in either event, to pay at the same times

as the rent is payable hereunder a sum equivalent

to such rent; and the Landlord may rent the prem

ises on behalf of the Tenant, (for a period of

time beyond the original expiration date of this

lease, if it so elects), without releasing the Ten

ant from any liability, applying any moneys col

lected, first to the expense of resuming or obtain

ing possession, second to the restoration of the

premises to a rentable condition, and then to the

payment of the rent and all other charges due and

to become due to the Landlord, any surplus to be

rj2 paid to the Tenant, who shall remain liable for any

deficiency.

30. The Landlord agrees that the Tenant on per

forming the conditions and covenants aforesaid

shall and may peacefully and quietly have, hold

and enjoy the premises for the term aforesaid.

31. It is mutually agreed that the conditions and

covenants contained in this lease shall be binding

upon the parties hereto and upon their respective

successors, heirs, executors, administrators and

assigns.

70 Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint

25

In W itn ess W hereof , the Landlord has caused

these presents to he signed by its authorized officer

and caused its corporate seal to be hereto affixed

and the Tenant has hereunto set his hand and seal.

B ethpage R ealty C oep.

By: ..................................................

Authorized Officer

Exhibit “ B ” , Annexed to the Complaint 73

Tenant 74

NO NOTICES WILL BE MAILED.

RENT IS DDE AND PAYABLE

ON THE FIRST OF EACH MONTH

AT THE RENTAL OFFICE

ON THE NORTH VILLAGE GREEN

If rent is paid by Check or Money Order,

please write job number on it.

75

26

A m e n d m e n t to th e A dm inistrative R ules, of the

F edera l H ousing C om m issioner U nder T itle

V I I OE t h e N ation al H ousing A ct

Section III of the Administrative Rules of the

Federal Housing Commissioner under Title VII

of the National Housing Act, issued November 12,

1948, as amended, is hereby amended by adding at

the end thereof the following new subsection:

77 “ 7. An investor must establish that no

restriction upon the sale or occupancy of

the project, on the basis of race, color, or

creed, has been filed of record at any time

subsequent to February 15, 1950, and must

certify that so long as the insurance con

tract remains in force he will not file for

record any restriction affecting the project

or execute any agreement, lease, or convey

ance affecting the project which imposes

any such restriction upon its sale or occu

pancy.”

78

This amendment is effective as to all projects

on which a commitment is issued on or after

February 15, 1950.

Issued at Washington, D. C., this 12th day of

December, 1949.

Exhibit “C” , Annexed to the Complaint

F ran k lin D. R ichards

Franklin D. Richards

Federal Housing Commissioner

27

(Letterhead of)

LEYITT AND SONS

INCORPORATED

August 3,1950

Mrs. Gertrude Novick

50 Honeysuckle Eoad

Levittown, New York

Madam: 80

You are hereby notified that your lease of prem

ises 50 Honeysuckle Road, Levittown, New York,

expires on November 30, 1950, and that you will

be required to vacate the premises on or before

that date. Upon your failure to do so, legal pro

ceedings will be immediately instituted to remove

you forthwith from the premises as a hold-over.

We are giving you this early notice, notwith

standing that there is no legal obligation on our

part to do so, so that you may proceed without

delay to find other housing accommodations. 8 l

79

Exhibit “D” , Annexed to the Complaint

W illiam F. I I aberm eh l ,

L evitt and S ons, I ncorporated

This is a motion by defendant to dismiss the

complaint for insufficiency. The action is for an

injunction and for declaratory judgment. Factual

allegations and the inferences which naturally flow

therefrom pleaded in a complaint when a motion

of this kind is made are deemed established.

(Locke v. Pembroke, 280 N. Y. 430.)

The complaint, given its best complexion al

leges : That plaintiffs are two families who reside

at Levittown, Nassau County, New York, occupy

ing their houses under written leases from defend

ant (VIII and IX)* expiring, by their terms, No

vember 30, 1950, but which “ are presently in

force” ( X ) ; that defendant, engaged in the con

struction business, has developed into a residen

tial community the hamlet known as Levittown,

Nassau-Suffolk Counties, by erecting therein about

ten thousand small homes of which about fifteen

hundred have been occupied by tenants of de

fendant (IV ) ; that construction of said homes was

financed “ with the aid of the Federal Housing

Administration * * *” and the mortgages on them

were insured by said Federal Housing Administra

tion “ conforming to various requirements of the

Federal Housing Administration” (V ) ; that plain

tiffs have not breached their leases (X I ) ; that it

is “ the policy, custom and practice of the defend

ant * * * just prior to the expiration date of a

lease, to send” a renewal form of lease to the

tenant with a letter of instructions, inviting the

tenant to sign same and return it to defendant

(X II ) ; that leases are always renewed unless the

Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J .

* (N ote) Roman numerals indicate paragraphs of the complaint.

Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J.

lessee “ breaches some provisions of the lease it

self and is” notified of such breach by defendant

(X III); that plaintiffs Ross’ leases in the past

“ have been thus renewed” (X IY ); that in the

past leases made by defendant and its subsidiaries

have contained a clause (not in plaintiffs’ ) by

which the tenant would agree not to permit the

use of the rented premises by negroes (X V ); that

if a lessee objected to the above clause defendant

would refuse to renew the lease (X V I); that the

said Federal Housing Administration, in June

1949, compelled defendant to remove the above

clause from its leases (XVII) and defendant did

so in form, but in fact continued to impose the

restriction upon tenants (X V III); that in July

1950 plaintiffs allowed negro children to use their

rented premises (X X I); that on August 3, 1950,

defendant wrote plaintiffs that their leases would

not be renewed; that they would be required to

vacate on the expiration date of their leases (No

vember 30, 1950) and failing to do so defendant

would take legal proceedings against them (com

plaint, Ex. D) (X X II ); that plaintiffs did not re

ceive the usual letter sent to a tenant just prior

to the expiration of his lease and no reason was

given by defendant for such omission (X X III);

that inquiry by plaintiffs of defendant as to

whether their leases were to be renewed brought

no reply (X X IV ); that plaintiffs received no com

plaint from defendant as to any violations of the

leases by them (X X V ); that upon information

and belief defendant’s refusal to renew plain

tiffs’ leases was based upon the incident in July

when plaintiffs allowed negro children to use the

demised premises (X X V I); that defendant “ has

30

an announced policy of refusing to lease or sell

property in Levittown” to negroes (X X V II); that

defendant’s action seeks to control its lessees’

guests contrary to the laws and public policy of

the state (X X V III); that any court which would

aid defendant to evict plaintiffs would violate the

public policy of the state and the United States

Constitution (X X IX ); that plaintiffs have no

adequate remedy at law (X X X ); that plaintiffs

are in constant, jeopardy of being evicted because

gg defendant has not renewed their leases (X X X I);

that unless an injunction is granted against de

fendant’s evicting plaintiffs, plaintiffs will suffer

irreparable damage (XXXIII and XXXIV). In

addition to the injunction, plaintiffs seek a judg

ment declaring in their favor many enumerated

rights.

The complaint is rife with allegations of evi

dence ; immaterial and irrelevant matters in addi

tion to conclusions of law and of fact. Defend

ant has made no objection on this motion to the

form or contents of the pleading; it is a straight

90 frontal attack that the complaint fails to state a

cause of action. Under such circumstances, Spe

cial Term should give the document a liberal

interpretation (Sec. 275, C. P. A.) in quest, if at

all possible, of some actionable wrong by defend

ant against the plaintiffs (Tripp, “ A Guide to

Motion Practice” (Revised) p. 243).

In his brief (p. 2) plaintiffs’ attorney states his

cause of action as follows:

“ The gravamen of the complaint herein

is that the defendant seeks to invoke the

aid of the courts of this state to evict the

88 Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J.

plaintiffs from their homes, which they had

leased from defendant, for the reason that

the plaintiffs invited Negro children to play

with their children on the said leased prem

ises in violation of defendant’s prohibition

against the use of said premises by persons

other than Caucasians.”

If that statement of plaintiffs’ case states a cause

of action at all (and I do not think it does), it

goes beyond the allegations of the complaint. But

to take the statement at its face value, its premise

is that defendant may not choose to whom it shall

rent its houses. Plaintiffs submit no support for

such a legal theory and I find the law to be to the

contrary. (Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68

S. Ct. 836; Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corpora

tion, 299 N. Y. 512, 536.)

Plaintiffs’ counsel states in his brief that

“ plaintiffs do not question the defendant’s

right to select its own tenants” (page 3),

but they do in the complaint and unless they deny

that right of choice to defendant, in their own

statement of their case, they have alleged no

actionable wrong.

Plaintiffs’ counsel asserts (brief p. 3) that the

right which the plaintiffs are projecting is that

defendants be prevented from invoking the proc

esses of a court to evict them. He bolsters that

argument up with the conclusion that defendant

has not renewed their leases because they (plain

tiffs) permitted negro children to use the demised

premises last July. There is no proper allegation

Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J.

Memorandum Opinion of Cuff, J.

in the complaint to support that contention, if a

proper allegation would make any difference.

Plaintiffs stress the fact that defendant wrote

them a letter (complaint, Ex. D) in which it stated

that if plaintiffs did not move from the rented

premises on or before the expiration of their

leases (Nov. 30, 1950), that legal proceedings

would be brought to evict them. There is no men

tion of discrimination in that letter; no reason is

assigned for the refusal to renew the leases. Of

course there was no provision in the leases even

referring to the subject of negroes, and although

the entity, Federal Housing Administration, is

freely disconnectedly and improperly used in the

complaint, the leased premises are a pure private

enterprise. The complaint does not even suggest

government subsidy or other financial interest.

There is absolutely no factual basis for the state

ment that defendant has declined to renew the

leases for the reasons assigned by plaintiffs. The

complaint fails to state any cause of action at all.

The motion to dismiss is granted with costs and

$10 motion costs.

T h om as J . C u f f ,

J . s. c.

33

Stipulation Waiving Certification

Pursuant to Section 170 of the Civil Practice

Act, it is hereby stipulated that the papers, as

hereinbefore printed, consist of true and correct

copies of the notice of appeal, the order appealed

from and all the papers upon which the Court

below acted in making the order appealed from,

and the whole thereof, now on file in the office of

the Clerk of the County of Nassau.

Certification thereof in pursuance of Section 616

of the Civil Practice Act, is hereby waived. 98

Dated, New York, N. Y., June , 1951.

R obert L. Carter,

J ack G reenberg,

C onstance B aker M otley ,

A ndrew D. W einberger,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

I ra G. G oldm an ,

Attorney for Defendant-Respondent.

97

99

(3716)