Furnco Construction Company v. Waters Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Furnco Construction Company v. Waters Brief for Respondents, 1977. a66bad84-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74b7d1c6-2bd6-428f-954f-6887c182e86c/furnco-construction-company-v-waters-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

219

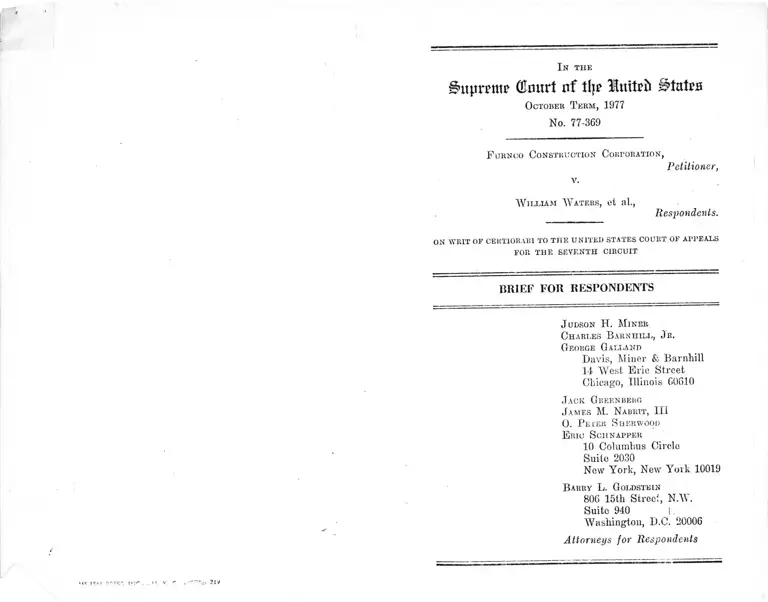

I n the

§>upx*pntc (Emtrt nf Jlj? Ĵ tateB

October T erm, 1977

No. 77-369

F urnco Construction Corporation,

Petitioner,

W illiam W aters, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS * 10

J udson H. Miner

Charles B arnhill, Jr.

George Galland

Davis, Miner & Barnhill

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabiht, III

0 . P eter S herwood

E ric Sen naffer

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New' York, New York 10019

B arry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940 I.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Attorneys for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Questions Presented .................................................... ' ^

Statement of F ac ts .............................—- .................... ^

The Three Plaintiffs ................................................. 9

Summary of Argument .............................. - ........... ----- 12

A r g u m e n t —

I. Plaintiffs Proved Intentional Racial Discrimina

tion Under McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green .... 15

A'. Plaintiffs’ Prima Facie Case .......................... 1*5

B. Fm-nco Failed To Rebut Plaintiffs’ Prima

Facie Case ......................................................... ^

1. Dacies’ Hiring Practices............................ I 8

a. Smith and Samuels................................ I 8

b. Nemliard................................................. 29

2. The Statistical Defense................................ 26

If. Furnco’s Failure To Hire Nemliard AY as The

Result Of Unlawful Perpetuation Of Infonlional

Discrimination ......................................................... 89

A. The Referral System......................................... 30

B. Prior Intentional Discrimination Against

Nemliard ............................................................ 33

III. Furnco’s Employment Practices Had The Effect

Of Discriminating Against Blacks And AVere Not

Justified By Business Necessity ............. - .......... 35

11

PAGE

A. Since The Seventh Circuit Did Not Consider

The Griggs Issues, A Remand Is Appropriate 35

B. Disparate Impact ............................................ 37

1. Dacies’ List ................................................ 38

2. Applicants ................................................. 45

3. Furnco’s Hiring Prior To October 10, 1971 46

C. Business Necessity ...... 48

IV. The “Clearly Erroneous” Rule Docs Not Require

Or Permit Affirmance Of The District Court’s

Judgment For Petitioner ..................................... 53

V. The “Questions Presented” In The Petition Are

Not Presented By This Case ............................... 61

Co n c lu sio n ............................................................. 62

T able of A u t h o h it ie s

Cases:

Albemarle Pager Co. v. Moody, 411 IT.S. 405 (1977)

37, 4a, 48

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) ............. 54

A miner man v. Miller, 488 F.2d 1285 (I).C. Cir. 1973) .. a.J

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 429

U.S. 252 (1977) ................................................... 17,23,27

Asbestos ll'orhers Local 53 v. Voglcr, 407 F.2d 1047

(5th Cir. 1969) ................................................... 13,30,31

Batiste v. Furnco Corporation, 3a0 F.Supp. 10 (N.D.

Til. 1972) ..............................................................7,8, 9, 29^

Baumgartner v. United States, 322 U.S. 665 (1944) .... 56

m

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Company,

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) ................................. 17> 34

Castcncda v. Partida, 51 I,Ed. 2d 498 (1977) ........ ..... 17

Denofre v. Transportation Inc. Bating Bureau, 532

F 2d 43 (7th Cir. 1976) ........................... .................. ,̂0

Dothard v. Bawliuson, 53 L.Ed. 2d 786 (19.7). 37, 41,48, 54

East v. Bomgue, Inc., 518 F.2d 332 (5th Cir. 1975) .... 56

Eubanlis v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 5S4 (1958) ................. -U

Flowers v. Crouch-Waller, Inc., 552 F.2d 1277 (7tli

Cir. 1977) ............................................................ "I-"18’ 5(>

Franhs v. Bowman Transportation Company, 424 U.S.

747 (1976) ................................................................. 33

Green v. Missouri Pacific Railroad Company, 523 F.2d

1290 (8th Cir. 1975) ................................................... 42

Origasx. Pule Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ....14,26,30,

35, 36, 37, 38, 41,43, 44, 46, 48, 49, 50, 62

Harrison v. Indiana Auto Shredders Co., 528 1‘ .2d 1107 ^

(7th Cir. 1976) ................................................... 33

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 53 L.fcrt

2d 768 (1977) .................................._..... y ..............

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) .................... 3

In re Las Gorlinas, Inc., 426 F.2d 1005 (1st Cir.

1972) .......................................................................... 55

Interstate Circuit Inc. v. United States, 306 U.S. 208 ^

(1939) ................................................... ............... • 19

James v. Stochham Valves and Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977) .................................................

PAGE

55

IV

PAGE

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5tli Cir.

1968) .......................................................................... 29

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire J Rubber Co., 491 F.2tl 1364

(5th Cir. 1974) ....................................................... 41,53

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 1S9 (1973) ....17, 23

Kinsey v. First Regional Securities, Inc., 557 F.2d 830

(D.C. Cir. 1977) ........................................................ 17

Kirkland v. ATew York Stale Department of Correc

tional Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361 (S.D.N.Y.) ........... 42

League of United Latin American Citizens v. City of

Santa Ana, 410 F.Supp. 873 (D.C. Cal. 1976) .......... 42

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)

12,14,16,17, 36, 40, 54, 57, 58, 62

Martinez v. Dixie Carriers, 529 F.2d 457 (5th Cir. 1976) 53

Norris v. Alabama, 394 U.S. 586 (1935) ........................ 54

Owen v. Commercial Union Fire Ins. Co. of New York,

211 F.2d 488 (4th Cir. 1954) ..................................... 53

Durham v. Southwestern Bell-Telephone, 433 F.2d 421

(8th Cir. 1970) ............... ...................................... 31,32

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257 (4th

Cir. 1976)..................................................................... 27

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939)........................ 19

Recce v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ............................ 54

Bitter v. Morion, 513 F.2d 942 (9th Cir. 1975) ............ 53

Roberts v. Boss, 344 F.2d 747 (3rd Cir. 1965) ............. 55

Rock v. Norfolk and Western B.B., 473 F.2d 1344 (4th

j Cir. 1973) ................................................................... 31

v

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 (8th

Cir. 1975) .............................-..................................; - 42

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972) .........................................................................17,53

Sellers v. Wilson, 123 F.Supp. 917 (M.D. Ala. 1954) .... 24

Senior v. General Motors, 532 F.2d 511 (6th Cir. 1976)

17, 53

'The Severance, 152 l*1.2d 916 (4th Cir. 1945) ..... ........ 55

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ..........................•- ^

Smith v. Troyan, 520 F.2d 492 (6th Cir. 1976) ............ 42

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 366 F.Supp. 87 (E.D.

Mich. 1973) .......................................................... 31

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445 (7th

Cir. 1976) ....................................................... 17

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) .... 16.20,

27, 28, 29, 33, 35, 57, 61

Tcrminicllo v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) .................... 36

United Stales v. El Paso Natural Gas, 376 U.S. 651

(1964) .......................................... -............................. 53

United Stales v. Forness, 125 F.2d 928 (2d Cir. 1942) 55

TTnitcd Slates v. Georgia Power Co., 414 F.2d 906 (;>th

Cir. 1973) ....................................................... ---....... 32

United States v. Ironworkers Local No. 8, 315 F.Supp.

1202 (W'.ll.W'ash. 1970) .............................................. 23

United States v. Matlock, 514 U.S. 164 (1974) ............. 4

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, etc., Local ,?f>,

.416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) .................... ■■-i:!::.......24,33

United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 374 U.S. 174 (1973) 53

United States v. United Stales Gypsum Co.K 333 U.S.

364 (1948) .............-........ .....................'■'"7.7,7''’.......53,54

PAGE

M l ! •

VI

Ward v. Apprice, 6 Mod. 2G4, 87 Eng. Rep. 1011 (Q.B.,

1705) .................................................. 19

1 Vhclan v. Penn Central Co., 50.3 F.'2d 88G (2nd Cir.

1974) .......................................................................... 53

Whit us v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (19G7) .................... 41,54

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 19G4.................passim

Executive Order 11246 ......... 41,47

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 52(a) ........53,55

Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 615 ......................... 58

Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 801 ......................... 4

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

42 F.R. 65512 (Dec. 30, 1977) ................................... 43

J. Wigmore, A Treatise on the Anglo-American System

of Evidence (3rd Ed. 1940) ........................................ 19

Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure,

§ 2578 (1971) .............................................................. 55

Code of Judicial Conduct, Canon 3(A)(3) ................... 59

PAGE I n t h e

intpnmte (Enurt nf tljc States

OoToiiER T erm, 1977

No. 77-369

F urnco C o n stru ctio n C orporation ,

Petitioner,

v.

W i ix ia m W aters , et ah,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Questions Presented

1. a. Does an employer violate Title VI1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 when its job superintendent fills posi

tions bv hiring from an all-white list of bricklayers from

which black plaintiffs have been intentionally excluded

on account of their race?

b. Was the job superintendent’s claim that he did not

consider applicants who sought employment by coming to

the job site—the only method by which blacks bad his

torically obtained employment with the employer a pre

text for discrimination?

2. Did plaintiffs’ establish that Furnco’s hiring prac

tices, including its preference for former employees from

2

a period when it hired only whites, perpetuated the effects

of past intentional discrimination?

I

3. When qualified black joh applicants are rejected be

cause of an employer’s hiring practice that excludes blacks

from most of its jobs and that is not justified as a busi

ness necessity, can the employer defend against Title VII

liability to those applicants on the ground that it has

filled certain jobs with other blacks under an “affirmative

action program”?

4. Did the Seventh Circuit err in declining to apply

the “clearly erroneous” standard to the district court’s

ultimate findings on the discrimination issues when the

district court misunderstood the hiring practice that plain

tiffs were challenging, misconceived the controlling legal

principles in plaintiffs’ lawsuit, and failed to consider

plaintiffs’ case in a fair and impartial manner?

5. Since the issues upon which certiorari was obtained

are not presented by this case, was certiorari improvi-

dcntly granted?

Statement of Facts

The question before this Court is whether three fully

qualified and experienced black bricklayers, plaintiffs

Smith, Samuels and Xendiard,1 were discriminatorily de

nied employment by petitioner Frrnco when it refused

1 Originally there were five additional plaintiffs. Two, Williams

and Gilmore, were found not to have applied at the Interlake job

and were denied relief. Onp, William Waters, was found to have

been denied a job because he had been discharged by the super

intendent from a job in 4002. Finally, two, Pearson and Hawkins,

were lured at a later stage of the job and then fired; the trial court

found that the firing was for cause. These findings were affirmed

by the Seventh Circuit.

3

to consider them for employment and subsequently filled

8b percent of its jobs from an all-white list. In its State

ment of Facts, Furnco described the type and the require

ments of the work performed, its alleged program to hire

a certain percentage of minorities, some general facts con

cerning hiring at the Tnterlakc job and the conclusoiy

findings of the district court. Consistent with its view

that it acquired immunity from further scrutiny under

Title VII by hiring a certain percentage of minorities,

Furnco’s brief describes neither the details of its hiring

practices, historically or at the Interlake job, nor the spe

cific circumstances concerning the refusal to hire the re

spondents. Notably omitted was any explanation of the

origin or use of the all-white list from which most of

Furnco’s bricklayers were selected. Because these facts

are essential to the resolution of this case, we summarize

the relevant evidence.

Furnco contracts with companies to do construction

work, primarily the relining of blast furnaces. These jobs

may last from several months to over a year. Furnco does

not maintain a permanent work force of bricklayers.

Bather, the company hires a superintendent for a specific

job who is responsible for hiring the employees. Mr.

Wright, the vice-president and general manager of Furnco,

agreed that “each superintendent is free to fill the joh

as he sees fit.” 1 This procedure depends on the practices

of individual supervisors and results, according to A\ right,

in bricklayers being selected in many different ways. The

superintendent may hire bricklayers whom he knows, may

request referrals from supervisors or from bricklayers, or

may recruit and screen possible employees in any other

way he chooses. (Tr. 671).

2 Tr. G8G; see Brief of Petitioner p. 6.

4

All of the superintendents selected by Furnco to oversee

bricklaying jobs in the Chicago geographical area have

been white. (Tr. G93). The record indicates that prior to

1969 Furnco had never hired a black bricklayer.3 In 1969

one or more superintendents employed by Furnco began to

hire black bricklayers by accepting applications made by

black bricklayers at the site of a Furnco joh at the South

Works plant of United States Steel Corporation.4 Respon

dent Smith was hired subsequently at another Furnco job

in 1971 after he had applied at the entrance gate. (Tr. 315).

Prior to the Interlake job involved in this case, every black

bricklayer hired by Furnco obtained employment by apply

ing at the job site. Furnco’s supervisors recommended

that black bricklayers in search of work apply in this man

ner for work on the Interlake job. (Tr. 237, 327).

Prior to the Interlake job in 1971 Furnco had operated

what was, in effect, a dual hiring system. Black brick

3 Waters, a plaintiff, testified that, lie had personally heard

Furnco superintendents Urban ski and Larkin testify before the

Illinois Fair Employment Practices Commission that Furnco to

their knowledge had not hired a black before 1969. Tr. 513-14.

This was admissible as an admission by a party opponent. Rule

801(d)(2), Federal Rules of Evidence; cf. United Stairs v.

Mattock, 415 U.8. 104, 172. n. S (1074). The black plaintiffs who

bad been working in the firebrick industry in the Chicago area for

many years had not been omph yed by Furnco before 1900. Furnco

offered no proof that it had, hired blacks prior to 1909 or that.

Waters had not accurately described the testimony of T'rbanski

and Larkin. Furnco's failure to do so is hardly surprising in view

of the fact that the company was represented at the F.E .l’.C.

hearing hv the same counsel who represented it in this case. At

that hearing Larkin, for example, testified, “I have worked for

. Furnco since almost they have been Furnco. . . . To tell the truth,

I don’t recall any colored bricklayers on any other jobs (prior to

. that in 1909].” Transcript of Hearing of August 10, 1970, pp.

! 203-05.

. 4 Four black bricklayers gave uncontroverted testimony that they

' applied for jobs at the gate at the South Works job and were hired''

by Furnco: Samuels. Tr. 234-30; Smith, Tr. 314-15; Waters, Tr.

509/; Pearson, Tr. 502.

5

layers were hired by Furnco only after they applied for

work at the* job site.I 5 6 White bricklayers were hired by be

ing personally contacted by the job superintendent or by

being referred by foremen or other Furnco bricklayers.6

The critical obstacle to minority employment was the fact

that Furnco never advertised, posted notices of, or other

wise made generally known the existence of vacancies at a

given site. Black bricklayers had to learn of these secret

vacancies through rumor and surmise, while white biick-

layers were individually recruited and told of the job op

portunities. For the Interlake job this dual hiring practice

was affected by two factors: pending litigation and the

particular superintendent, Joe Dacics, hired by Furnco.

Facies had worked in the firebrick industry since 1939.

(Tr. 767). Facies was first employed by Furnco in 1964

as a bricklayer and in 1965 as a superintendent. Facies

hired 85 percent of the bricklayers for the Interlake job by

referring to a list which he maintains. (Tr. 769) :7 *

5 The black workers who had previously worked for Furnco had

never prior to the Interlake job been called by a Furnco superin

tendent and requested to report for work without having fust

presented themselves at the particular job site and requested work.

6'Furnco in its statement of facts states that it was not the

“practice” of Furnco or the industry to accept applications. The

district court so found, A14-15. As to Furnco this is true only

for white employees.

The Court’s findiugs and Furnco’s statement as to the industry

are inconsistent with their opposition at trial to' the consideration

of evidence as to the industry practice. Counsel for Furnco

argued strenuously in objecting to the plaintiffs attempt to intro

duce evidence, as to industry practice that the evidence was

irrelevant. Tr. 59, 241-44. The Court at one point simply

stated, “I’m not interested in what the practice is in the industry.

Tr. 561. See infra at n.34. The Court rejected plaintiffs’ proffered

evidence on the ground that the issue was irrelevant, but subse

quently resolved the issue in defendant’s favor.

7 Dacies routinely filled the job with employee? on his list. Tr.

769-70. In fact, 30 of the 37 whites who were hired by Furnco

6

"Well, I have a list of bricklayers. There are various

notes, I don’t have a direct file system, but it is people,

prior to even working with Fnrnco, I had worked with

bricklayers all over the country, and in this area. I

have kept their telephone numbers, because they were

good mechanics. So when I have a job, 1 try to con

tact them.

1 hides’ list did not contain a single black bricklayer,8 even

though Dacies had worked with black bricklayers since

1958, had supervised five to eight black bricklayers in

1962 for another contractor (Tr. 873), and had supervised

jobs for Fnrnco in 1969 and in 1971 on which blacks were

employed. (Tr. 777; 873-75).9 Respondent Smith had

worked for Dacies on four separate occasions (Tr. 343-45)

and respondent Samuels on one occasion.10 11 Neither Dacies

between August 2G and the end of September were called by

Dacies from bis list; the 37th was recommended by one of the

white bricklayers whom Dacies had hired from the list. Tr. 780-86;

Joint Exhibit 1.

8 Dacies testified.

“Q. Now, did you know the names of any black bricklayers?

A. 1 knew a couple that was at South Works, but T didn’t

have their addresses or telephone numbers. . . ..”

Tr. 778.

9 The record is vague ns to h w many jobs and how many black

bricklayers Dacies supervised, because the district court ruled

that “It does not make any difference how many jobs he super

vised” and sustained an objection by Furnco’s counsel to questions

concerning Dacies’ work history. Tr. 874-75.

10 Although Samuels did not recall working with Dacies, it is

clear from Dacies’ testimony that they worked together on the

D.S. Steel South Works job in 1969. Dacies worked as a super

visor on the job (Tr. 806. 874-75), while Samuels was the third

black hired and worked at least five months as a bricklayer on the

job. Tr. 234, 249. Although Samuels was hired (Tr. 235-36) and

directed (Tr. 266) by another supervisor, Dacies had an oppor- ^

tunity on this job to become familiar with Samuels’ work.

7

nor Furnco offered any explanation why Smith, Samuels

or other qualified and experienced black bricklayers known

to Dacis were excluded from the list.

Dacies’ customary hiring practice was modified on the

Interlake job by Furnco’s response to prior charges of

discrimination and to the pendency of a related Title VI1

case.11 Wright, a company general manager, testified that

he called Dacies prior to the commencement of the job and

said that Furnco wanted him to hire “a minimum of 10 per

cent black bricklayers on the job if at all possible”. (Tr.

075). Work began on the Interlake job on August 20, 1971,

and continued through November. Between August 20

and September 30, Dacies employed 41 bricklayers, of

whom 37 were white. (Joint Exhibit 1). Thirty-six of the

37 whites were hired by Dacies from his all white list;12 the

4 blacks were employed after Dacies contacted another

Furnco superintendent, Mr. Urbanski.13 Two of the blacks

The district court erroneously prevented plaintiffs’ counsel from

inquiring as to the extent of this opportunity. Tr. 875:

“Q. [By plaintiffs’ counsel] Could you [Dacies] tell me who

these black bricklayers were [with whom he recalled work

ing on the South Works job] ?

Tiie Court : The objection is sustained [there was no objec

tion]. It doesn’t make any difference who they were. The

thing involved here is Furnco’s policy about hiring brick

layers and not what some other policy was on some other

years before."

Plaintiffs’ counsel argued that the question was proper and

relevant. But the district court ruled, “You may think it [the

question] is [relevant], but I am not concerned about review of

»ai/ objections either”, (emphasis added) Tr. 876.

11 Batiste v. Furnco Corporation, 350 F.Supp. 10 (N.D. 111.

1972), rrv’d 503 F.2d 447 (7th Cir. 1973), ccri. denied 420 U.S.

928 (1975).

12 See supra at n.8.

13 One of the four blacks was actually hired upon the recom

mendation of his brother whom Urbanski had referred to Dacies.

Tr. 781.

8

employed in this period were not in fact hired at all, but

were merely transferred from another Furnco job to the

one at Interlake.14

The focus of this case is on the hiring by Furnco in Au

gust and September. Settlement negotiations in a related

Title VII case between Furnco and several black brick

layers, including the, plaintiffs in this case, began in the

summer but broke down towards the end of September.

After the termination of the settlement talks and after

several of the plaint ill’s in this action had filed charges with

the E.E.O.C.,15 16 Wright telephoned Dacies and instructed

him to consider hiring several black bricklayers involved

in those negotiations. (Tr. 678, 77S-79). Between October

12 and 18 Dacies hired six workers, all black bricklayers

who were among those mentioned by \\ right to Dacies,

whom Wright and Dacies knew were threatening legal

action against Furnco, and who were the ‘ focus of the

settlement negotiations.” (Tr. G77).1G Thereafter Dacies

14 One black, 1LD. Jones, testified that Larkin, a Furnco foreman

approached him on the Bethlehem job and told him to report for

work at Interlake. Tr. 913-14. Plaintiffs offered into evidence, as

their exhibit 10, a list of employees on the Bethlehem job

which Furnco was operating contemporaneously with the Interlake

job. This list was supplied as part of Furnco s Answers to Imei-

romitories Tr. 331. Ii indicates that Joseph Alston, a black brick

layer, was employed on the Bethlehem job until September 7,

1971; the following week he was employed on the Interlake job.

Joint Exhibit 1. Clearly, Alston like Jones was transferred to the

Interlake job. The district court erroneously denied the plaintiffs

offer of the exhibit because ‘i t does not prove a thing.” Tr. 383.

However, counsel for Furnco subsequently asked B.D. Jones a

question concerning the list. Tr. 920, and the district court stated

to Furnco's counsel “1 don't care whose exhibit it is. As lie [plain

tiff's’ counsel] said, you made it up and you have got it here .

Tr. 922.

15 See Pre-trial Order, p. 5; Tr. 139, 201, 494, 608.

16 The six men hired were William Smith and Willie Pearson

(plaintiff’s in this ease). Sylvester Williams and Vainly Hawkins

(plaintiffs in both this case and the Dative case), and Charles

9

resumed hiring from bis usual list, employing seven addi

tional workers, all white, until the completion of the job.

The Three Plaintiffs

The three plaintiffs for purposes of this appeal are A1) il-

liam Smith, Donald Samuels and Robert Nemhard. All

three are competent bricklayers who had between 18 and 30

years experience in their craft at the time of the trial,17

and had firebrick experience.18 All three sought employ

ment on the Interlake job by going to the job and.attempt

ing to leave their telephone numbers with the superinten

dent.19

AVilliam Smith has worked continuously as a bricklayer

since 1944 (Tr. 311), and first worked on a firebrick job m

19A0 (Tr 311). Furnco stipulated at trial that Smith was

both experienced and qualified. (Tr. 313-14). Smith first

worked on jobs with Dacies in 195S and again in 1962. (Tr.

343-5). In 1969, Smith first secured employment on a

Furnco job at the U.S. Steel South AVorks plant by going

to the joli site, where he was hired by a Furnco foreman.

(Tr 314-15). Dacies was Furnco’s assistant superintendent

on that job. After the South AVorks job, Smith applied for

employment on a Furnco job at the Bethlehem Steel Mill

Indiana bv going to the gate and leaving his name and

telephone number. AYhile he was not hired on that particu

lar job, he reapplied in 1971 for another. Furnco job at

the Bethlehem Mill bv going to the Arid on a number of

occasions and was ultimately hired by Furnco’s bricklayer

Temple and Raymond Pendarvis (plaintiffs in the Batiste case

only). All six were among the alleged victims df discrimination

being discussed in the Batiste negotiations.

17 Tr. 66, 227, 310. J,'

18 Tr. 66, 229-35, 310-15.

15 Tr. 74-8, 327-30, 519-24.

10

superintendent on that job, Albert Urbanski. Dacies was

also employed on this job as the Assistant Superintendent

and thus the two men worked together for the fourth time.

(Tr. 315, 32(5-7). At the time he was laid off the Bethlehem

job, Smith was told by Urbanski that there would be a

Furnco job at Interlake and according to Smith, Urbanski

said, “I don’t know who is going to run the job but . . . if

you go there you might got on.” (Tr. 327). As suggested by

Urbanski, and consistent with the way he had secured

every other job he had ever worked in the firebrick in

dustry—including all Furnco jobs—Smith began going to

the Interlake job site to seek employment. Smith testified

that he went to the site on numerous occasions and had

seven or eight conversations with Dacies between the time

Dacies first appeared in August and the date Smith was

eventually hired, October 12, 1971. (Tr. 327-30). Dacies

could specifically recall only one conversation with Smith

and Dacies testified that he had said “You can go—you

might as well go home, Smitty. I will call you when the job

is ready, when I am ready to hire people.” (Tr. 871). How

ever, Smith was not called when Dacies was hiring in

August and September, 1971, and was not hired until

October 12, 1971.

Donald Samuels lias been a bricklayer since approximately

1957. (Tv. 227). Beginning around 1957 Samuels worked

for six or eight different firebrick contractors prior to the

Interlake job. (Tr. 229-34). Samuels first worked for

Furnco, Dacies and Urbanski on the U.S. Steel South Works

job in 1909, after having gone to the job site and applied

to Larkin, a bricklayer foreman. (Tr. 235-7). lie worked

for Furnco on the South Works job for approximately five

months. Samuels next sought employment with Furnco

at the Interlake job in August, 1971. According to Samuels,

he went to the job site on three or four occasions. (Tr."

11

249-59). On one occasion he and another of the plaintiffs

stopped Dacies’ car as Dacis was leaving the job site, told

him they were bricklayers looking for work and slipped a

piece of paper with their names and telephone numbers, as

well as the names and phono number of two other black

bricklayers, into the side vent window ot the car. Howcvci,

Dacies merely “balled it up and threw i t . . . on the ground.”

(Tr. 521-2; Plfs. Ex. 7). Samuels also recalled a second

conversation with Furnco’s general superintendent in which

the superintendent was asked to tell Dacies that thoie wcic

bricklayers at the gate looking for work. The superinten

dent returned to tell them that Dacies was not hiring. (Tr.

25S-9, 524). Samuels was never hired on the Interlake job.

Robert Nemhard has worked as a bricklayer since 1945

and, before Interlake, had worked two firebrick jobs. (Tr.

G6, 68, 72). Nemhard began going to the Interlake job in

August and continued to visit the site through mid-Septem

ber. (Tr. 74-6). Nemhard testified that on a number of

occasions he sought to speak to Dacies, but that Dacies

had avoided him. (Tr. 74). On one occasion, while trying to

speak to Dacies, he was almost run over by Dacies’ car.

As a result of that incident, Nemhard wrote a letter to

Furnco expressing his outrage at its superintendent’s

conduct and asking the company for a job. (Tr. 76-79).

Nemhard never succeeded in talking with Dacies. Like

Samuels, Nemhard was never employed on the Int'-rlake

j°b.20

20 Dacies testified that lie did not know that there were any black

bricklayers seeking work at the gate. (Tr. 8C8). '(he trial court

made no finding as to this matter and Dacies’ testimony is difficult

to reconcile with the facts that: (a) Dacies recalled at least one

conversation with Smith at the job; (b) Dacies recalled that Ins

ear Was stopped by Samuels and that he was slipped a piece of

paper; (e) Dacies’acknowledged that on a couple of occasions a

"Hard'called him to tell him that there were bricklayers looking

for work (Tr. 869-70) ; and (d) Smith testified to a subsequent

*£? ■

V

12

Respondents sued Furnco because they were not hired

when they sought to apply in August, 1971, although 4421

white bricklayers who had never sought jobs, and whose

qualifications were not better Ilian those of respondents,

were hired after respondents were rejected.22

■

Summary of the Argument

Furnco’s argument fails to address the specific details

of its hiring practices—particularly the use of Dacies’ all-

white list—which led to the refusal to hire plaintiffs.

I. Plaintiffs unquestionably proved that they were black,

were qualified bricklayers, had sought work at Furnco, and

had been rejected, and that Furnco subsequently recruited

and hired at least 37 white bricklayers. This evidence was

sufficient to establish a prima facie, case under McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), and shifted the

burden to Furnco to prove a legitimate, nondiscriminatory

business reason why plaintiffs were rejected. Furnco failed

to carry that burden.

Furnco attempted to justify the rejection of plaintiffs

by asserting that their supervisor, Dacies, followed a policy

of not accepting applications at the job site and of hiring

instead off a list of bricklayers known to him personally.

This was inadequate to explain why plaintiffs Smith and

conversation with Dacies in'which Dacies said that lie was not

hired earlier because lie was with ‘‘those other fellows’’ (Tr. 334),

a conversation Dacies never denied.

21 Of the 44 whites hired by Dacies, 42 were hired in September

and October. Respondents had sought work at the Interlake site

in August.

1 22 Samuels and Nemhard were never employed at the Interlake

job. Between Smith’s initial rejection and Dacies’ decision to hirtT

him in October, 37 white bricklayers were hired.

13

Samuels were not hired, since both Smith and Samuels

were known to Dacies and had worked with him on Fuinco

jobs in tbe past. Furnco gave no explanation why Dacies

had neither put Smith or Samuels (or any other black

bricklayer) on his list nor called thorn when he knew they

were looking for work. More broadly, the evidence over

whelmingly showed that Dacies’ refusal to accept applica

tion at the job site was a pretext for discrimination.

Furnco also attempted to rebut plaintiffs prima facie

case by showing that Dacies had, at the insistence of a

higher company official, hired a percentage of blacks al

leged to be comparable to tbe minority percentage of the

area work force. This action was irrelevant to Dacies’

motivation, since it occurred at tbe direction of a different

Furnco employee. “Affirmative action” which benefits one

group of blacks cannot constitute a defense to claims of

other blacks who were the victims of intentional discrimina

tion.

II. Dacies’ practices limited hiring to persons known

to him or referred by another Furnco employee. These

practices perpetuated tbe effect of past discrimination by

Furnco and Dacies in two ways.

First, special treatment for persons referred by Furnco

employees necessarily perpetuated any past discrimination

in the selection of Furnco employees. Asbestos II orlcers

Local 53 v. Vogler, -i07 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969). By in

tentionally discriminating against Smith, Dacies foreclosed

the one remaining avenue to employment for blacks not

known to Dacies or Furnco but only known to Smith. Re

spondent Nemhard was injured in this manner since be

was an acquaintance of Smith and had applied to Furnco

with Smith.

Second, the record demonstrated that Dacies and Furnco

had a history of racial discrimination prior to tbe Inter

14

lake job. Furnco bad not hired any blacks prior to 19G9,

and thereafter operated separate hiring systems for blacks

and whites. Dacies had never hired a black prior to the

Interlake job. These discriminatory practices prevented

plaintiff Nemhard from acquiring experience with Dacies

or Furnco, and Dacies’ prior experience requirement oper

ated “to freeze the status quo of prior discriminatory em

ployment practices.” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424, 430 (1971).

III. This case presents a variety of important legal

issues as to (he meaning of disparate impact and business

necessity under Griggs. The court of appeals, however,

never considered these issues, since it concluded that plain

tiffs had established intentional discrimination under

McDonnell Douglas. Although the district court rejected

plaintiffs’ Griggs argument in a conelusory manner, its

opinion contains no consideration of the legal theories

pressed by petitioner and respondents. Accordingly, re

spondents urge that this Court not address these issues, but

remand them instead to provide the court of appeals with

an opportunity to do so.

Should this Court not do so, respondents offer three bases

for finding a disparate impact under Griggs. First, Dacies’

practice of filling the bulk of the jobs with an all-white list

violated Griggs because it excluded blacks from all jobs

filled off that list. Second, only blacks sought to apply for

work at the gate, so only blacks were adversely affected by

Dacies refusal to consider such applications. Third, during

the relevant time frame, Furnco’s practices resulted in the

{hiring of a minority work force of only 5 percent, compared

■ with a relevant labor market that was actually at least 13.7

'percent black. Furnco failed to establish that the disputed

practices were required by business necessity.

15

IV. The Seventh Circuit properly declined to apply the

“clearly erroneous” standard to the findings of the district

court. The findings themselves are conelusory and fail to

address most of the contested factual issues. I he findings

provide no indication as to the District Judge’s view of

the legal significance of the evidence adduced by plaintiffs.

The District Judge totally misconceived the controlling

legal principles of Title VII and erroneously excluded

much of the evidence afforded by plaintiffs. Having re

jected some of this evidence on the ground that it related

to irrelevant issues, the judge then ruled for the defendants

on those issues and relied on those findings in rendering

decision for defendants. The findings of the District Judge

were apparently written by counsel for defendant after the

case was decided, and thus provided no guide as to the

reasoning that led the judge to rule in favor of defendants.

Finally, the trial of this action was punctuated by intemper

ate and unwarranted remarks by the District Judge directed

at the court of appeals, Title VII, plaintiffs and plaintiffs’

counsel.

V. The “Questions Presented” asserted in the Petition

for Writ of Certiorari are not in fact presented by this case

at all. The court of appeals did not hold that evidence ot

substantial minority employment is “irrelevant,” or that

“discriminatory effect” can lie found in the absence of

“disparate impact.” Petitioner’s brief does not focus on

these issues, but deals largely with arguments not fairly

comprised within the questions presented. Under these

circumstances, certiorari was impro\idently gianted.

\*t' ■

16

A R G U M E N T

I.

Plaintiffs Proved Intentional Racial Discrimination

Under McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green.

A. Plaintiffs’ P rim e Facie Case

In McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,* 23 * 411 U.S. 792,

800 (1973), this Court considered “the order and allocation

of proof in a private, non-class action”. The plaintiff

meets his burden by showing that be is qualified, a member

of a racial minority group, and “bad unsuccessfully sought

a job for which there was a vacancy and for which the

employer continued thereafter to seek applicants with sim

ilar qualification”, Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

358 (1977). There is no question that the plaintiffs in the

instant case belong to a racial minority, that “they did

what they could to apply”,54 that they were qualified, that

they were rejected and that Furneo thereafter hired more

than 37 white bricklayers who, unlike plaintiffs, had not

even sought employment at Interlake, and whose qualifica

tions were not demonstrably better than plaintiffs’.

That was all plaintiffs were required to show to estab

lish a prima facie case under McDonnell Douglas and

Teamsters.25 * In addition, plaintiffs demonstrated that

23 The court of appeals carefully followed the McDonnell Douglas

standards in analyzing the evidence. AG, A9. The district court

did not consider those standards at all.

24 Both the district court (A17) and the court of appeals (AG)

found that, the respondents sought employment. The white brick

layers. on the other hand, never had to seek work at Furneo or

express any interest in being hired.

25 Furneo does not deny that plaintiffs proved the four elements

of a prima facie case identified in McDonnell Douglas, but ap-

17

Furneo had established no objective standard to he applied

in selecting bricklayers, but had left Daeics “free to fill the

job as he [saw] fit”. (Tr. G86). The standardless discretion

thus afforded to Dacies by Furneo was the type of system

which this Court has repeatedly warned “is susceptible of

abuse” and thus buttresses plaintiffs’ prima facie case.

See Castcncda v. Partida, 51 L.Ed. 2d 498, 512 (1977).

B. Furneo Failed To Rebut P laintiffs’ Prim a Facie Case

Once plaintiffs established this prima facie case, the

burden27 shifted to Furneo to rebut it by establishing “some

legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason” for the refusal to

hire, McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S.

at 802. Furnco’s burden was to present sufficient proof to

demonstrate that discriminatory “intent was not among

the factors that motivated” the failure to hire the plain

tiffs, Kegcs v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 1S9, 210

(1973) ; cf. Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977).

nnrentlv urges that plaintiffs were also required to prove a fifth

element, “discriminatory motive or intent”. Brief of Petitioner,

pp 45-50. Evidence establishing those four elements is a pnam

facie ease of such motive or intent. Teamsters v. I mted States, 4 41

U.S. at 335, n .l5, 358, n.44.

23 Six Circuits have held that employment decisions which

depend upon the subjective evaluation of an immediate forum

and which are not reviewed are “a ready mechanism forOisrmnnina

tion". Rowe v. Genual Motors Corp.. 457 F.2d 348 3o9 (ot i Fir.

1972); Kinsey v. First Regional Securities Inc., o.u h -d 8-iJ,

838 (D C Cir 1977); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine

Company, 457 F.2d 1377, 1383 (4th Cir. 1972) errf denied 409

IT 8 86° (197°) ; Senior v. General Motors, o32 F.2d o il, o_8 (6th

Cir' 1976) cert, denied 429 U.S. 870 (1976); Stewart v General

Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445, 450-51 (7th Cir. 1976) cert denied

54 L.Ed 2d 1105 (1977) ; Muller v. United States Steel Coip.. oO.)

F.2d 923 (10th Cir.), cert, denied 423 U.S. 825 (lO/'o).

27 Both the burden of proof and the burden of going forward

with the evidence shifted to Furneo. It was the former which it

did not meet.

18

Although Furnco argues at length, and on this record

without foundation,28 * that laying firebricks is an extremely

difficult and specialized job, Furnco does not contend that

it rejected respondents because it believed them unqual

ified. Furnco stipulated that Smith was fully qualified.

Tr. 313-14. Samuels had extensive firebrick experience,

and had done such work for Furnco itself.20 Nemhard too

had firebrick experience, and Furnco concedes that in his

as in the other cases the “rejection for employment was

not the product of any determination as to their individual

qualifications”.30

Furnco sought to rebut plaintiffs’ prima facie case in two

ways. First, Furnco attempted to prove that plaintiffs

were rejected because Dacies had a practice of only hiring

bricklayers known to him and of refusing to accept or

consider applications. Second, Furnco urges that the pro

portion of blacks on the Interlake job was comparable to

that in the area work force, and contends that such evidence

is conclusive proof that it did not engage in racial discrim

ination.

I. Dacies Hiring Practices

a. Smith and Samuels: Furnco’s general rebuttal is

that the Company does not “hire at the gate”, that Facies

28 The president of the local bricklayers union testified that any

experienced bricklayer could do firebrick work if he were willing

to work hard. Tr. S29. Consequently, the union provides no train

ing or apprenticeship in firebrick work, and bricklayers who do

this work acquire the necessary skill through on the job training.

Tr. 58-59. Although a witness recalled a single instance in winch

a blast furnace exploded, no testimony was offered that this was

in any way connected to the brickwork involved Tr. 660.

29“ [T]he employer’s acceptance of his work with.out express

reservation is sufficient to show that the plaintiff was performing

satisfactorily. . . .” Flowers v. Crouch-Walker Corp., 552 F.2d 1277,

1283 (7th Cir. 1077).

30 Brief of Petitioners, p. 16.

19

only hired bricklayers known to him or who were referred

by an insider, a foreman or another bricklayer. Whether

this is true and, if true, whether motivated by racial con

siderations, are in dispute. But the dispute does not need

to he resolved as to Smith and Samuels. Smith had worked

with Dacies on four separate occasions; Samuels had

worked for five months on a job at the South Works of

U.S. Steel Corporation where Dacies was a supervisor.

Both were qualified bricklayers who had performed satis

factorily on Furnco jobs under the supervision of Dacies.

Furnco offered no justification of Dacies’ refusal to recruit

Smith and Samuels for the job as he recruited forty-two

white bricklayers with whom he had also previously

worked.31

The record reveals that Smith and Samuels were not

offered jobs merely because they, as all the other blacks

with whom Dacies had ever worked, were omitted from his

list. Dacies sought to justify this omission by asserting

that he did not have the telephone number of any black

bricklayers. (Tr. 778.) But he did not explain why he

had only recorded the telephone numbers of white brick

layers32 or why lie did not obtain the telephone numbers

31 The failure of Furnco to present evidence explaining why

Dacies did not recruit any of the black bricklayers who bad

formerly worked with him supports the inference that Dacies was

motivated by racial considerations. This evidentiary principle is

well-established. The Court of Queen’s Bench articulated the rule

over two hundred and seventy years ago:

[B]ut if very slender evidence be given against him, then, if

lie will not produce his books, it brings a great slur upon his

cause.

Ward v. Apprice, 6 Mod. 264, 87 Eng. Kep. 1011 (Q.B., 1705); see

also Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354, 361-62 fj'939); Interstate

Circui* Inc. v. United States, 306 U.S. 208, 221 (1939) ; 2 J. Wig-

more, A Treatise on the Anglo-American System of Evidence

§291 at 187 (3rd. Ed. 1940). ‘• ‘ i ,

32 There is no question that Dacies had worked with a number

of black bricklayers at many different jobs. The district court

20

of known black bricklayers from the company’s own rec

ords or the telephone directory. Despite Dacies’ knowledge

of Smith, Samuels and other qualified blacks, the number

of blacks on bis list remained the “inexorable zero”. Team

sters v. United States, supra, 431 U.S. at 342, n.23.

Dacies, moreover, did not need telephone numbers for

Smith and Samuels, since be met them personally at the

gate when they sought to apply for work at the Interlake

site. Most importantly, Dacies approached Smith at the

job site in August and stated “ [y]ou can go—you might

as well go home, Smittv, J will call you when the job is

ready, when I am ready to hire people” (Tr. 871). Despite

this representation Dacies did not call or hire Smith until

two months later, after he had recruited and hired thirty-

seven whites who bad not sought work on the Interlake

job, and only after be had been directed by Wright to

consider employing Smith because of the threat of litiga

tion.33

b. Nemharrh Since Nemhard was not known to Dacies

prior to the Interlake job, it is necessary in resolving his

claim to consider in detail whether Furnco’s asserted de

c-iToneously sustained Furncos objection to the plaintiffs question

directed to Dacies concerning the number of times he worked with

blacks and the number of blacks with whom he had worked. See

supra at n.lU.

In its brief petitioner suggests Dacies lacked these telephone

numbers because he had been working outside of Chicago prior to

the Interlake job. Brief for Petitioner, p. 8, n.8. Dacies himself

adduced no such explanation at trial. Nothing in the record sug

gests that Dacies had ever had a black on his list. The record shows

that prior to the Interlake job Dacies was employed by Furnco

■ at another job in the Chicago area. Tr. 343-44.

33 There is substantial evidence that Dacies did not hire Smith

because this might have led to hiring other black bricklayers as

well. See infra at p. 32.

21

fenses—that Furnco and Dacies do not “hire at tlie gate”,34

that they do not accept applications and that Dacies only

hires persons known to him or “referred” by another ap

propriate person35 * * *—are true and, if true, whether they were

neutrally motivated and applied. The record demonstrates

not only that Furnco failed to meet its burden of demon

strating such neutral motivation and application, but also

that these policies were a pretext adopted and manipulated

by Dacies in order lo minimize the number of black brick

layers at the Intcrlake job.

Insofar as petitioner suggests that Furnco had a prac

tice of not accepting applications at the gate, the record

in the case conclusively demonstrates that that was not the

case. No witness ever testified that Furnco in fact forbade

accepting such applications. Furnco’s general manager

Wright testified that the company imposed no rules what

ever on superintendents, but permitted them to hire as they

34 The difference between Furneo’s and Dacies’ practices is

obscured by the use of the phrase “hire at the gate.”

At times the phrase is used fairly literally to denote hiring as

bricklayers men standing at the gate of a job site without inquiring

into their skills and experience. Thus IVright testified Furnco had

a “policy”, admittedly not enforced, of not hiring at the gate

because there was no assurance of a man’s ability. Tr. 671. Sim

ilarly Larkin testified at the FEPC hearing that, although he did

take names of men at the gate and consider them for future vacan

cies, he did not “hire at the gate.” Transcript of hearing of August

10, 1670, pp. 200-207.

Petitioner uses the phrase to refer to “the accepting of applica

tions at the job site gate." Brief of Petitioner, p. 6, n.6. Thus

when petitioner asserts Furnco “never hired at the gate”, the

assertion is true literally but false in the sense intended by peti

tioner. See Appendix pp. 18, 19.

35 Petitioner in its brief variously describes the persons from

whom Dacies would accept a referral as another supervisor, a

Furnco bricklayer and any other reliable source. Brief of Peti

tioner, pp. 6, n.4, 8, 18, n.14, 21, 25, 26. The district court opinion

states somewhat ambiguously that Dacies hired those “who were

recommended as being skilled in such work.” A. 13.

22

saw fit. Wright suggested that he or the company had

“guidelines”, embodying possibly preferable practices, but

conceded that these were neither binding nor enforced and

offered no claim that they were adhered to by most or any

supervisors.36 The record makes clear that prior to the

Tnterlakc job blacks had in fact obtained employment with

Furnco by applying at the job site, and that this was the

only way blacks had been able to work for Furnco.37 Two

Furnco supervisors, Larkin and Urbanski, advised plain

tiffs that the way to get hired by Furnco was to apply at

the job site.3S The critical fact about the practices used

to exclude Nemhard is that thejr were fashioned and

adopted by Daeies, not imposed by higher management.

The issue is thus whether Daeies’ policies of hiring only

bricklayers whom he knew and of refusing to consider

blacks who applied at the gate—policies at variance with

those of other Furnco supervisors—were adopted and ap

plied in a nondiscriminatory manner. The evidence clearly

demonstrates that they Avere not.

First, Daeies’ policies were, as we have shown, inten

tionally manipulated to exclude Smith and Samuels on the

basis of race. Daeies’ creation and use of an all-white list,

excluding all blacks with whom he had ever worked, was an

act of intentional discrimination. If, as petitioner asserts,

Daeies had always applied the same practices and hired

from his list, that compels the conclusion that Davies had

never hired a black before the Interlake job, and demon

strates that the practices were part of a consistent policy

of racial discrimination. At the least these other acts of

discrimination by Daeies were “highly relevant to the issue

36 Tr. 68G.

37 See supra at nn.4-5.

3S Tr. 237, 327.

23

of [his] intent” in refusing to accept or consider applica

tions at the Interlake job. Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. at 207.

Second, Daeies’ decision to refuse to accept applications

at the gate abruptly sealed off the only avenue previously

open to blacks to get jobs with Furnco. Such departures

from past practice are inherently suspect. Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 4'2'J U.S. at 2G7.

Daeies apparently did not disclose this change in practice

to other Furnco supervisors, who continued to advise black

bricklayers to apply for work at the Interlake site. Al

though petitioner contends that this change in practice

would also have foreclosed whites from so applying, there

is no evidence in the record that whites had ever sought

employment in that manner.

Third, Daeies’ behavior toward the blacks who applied

at the gate was deceitful, hostile, and evasive. He lied to

Smith and others39 telling them he was not yet hiring,40 and

falsely told Smith he would call him when the job Avas

ready41 but did not do so. lie took the name and address

of another black bricklayer, Pearson, in August, but never

called him.42 On another occasion lie threw aAvay a list of

four qualified black bricklayers given him by Samuels and

32 Tr. 163-61, 251-52, 255, 457, 525, 556, S71.

40 The record makes clear that Davies commenced work as a

supervisor oil August 14, began recruiting whites within 10 days

and thereafter hired continuously until the end of September.

Although the exact dates of Daeies’ statements to the black

applicants are not clear, there Avas no time after he began work

Avlien it would have been accurate to assert that lie was not hiring.

Tr. 805. A similar false assertion that no work was availab'e was

condemned in United States v. Ironworkers Local No. 8, 315 F

Supp. 1202, 120G. 1207, 1208 (W.D. Wash. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d

544 (9th Cir. 1971).

41 Tr. 871.

42 Tr. 5GG-67.

24

Waters.43 He purposefully avoided Nemhard and other

blacks by leaving the job from different gates and by re

fusing to stop to talk to them, and on one occasion almost

ran Nemhard down while trying to avoid him.44 Such be

havior cannot be reconciled with the good faith policy peti

tioner alleges Dacies was following. Cf. United States v.

Sheet Metal Workers, etc., Local 36, 41G F.2d 123, 128, n.8

(8th Cir. 1969).

Fourth, and most importantly, Dacies never advised any

of the black job seekers of the hiring policies which peti

tioner asserts Dacies was following throughout this period

—that Dacies would not hire bricklayers applying at the

job site, that Dacies would not accept applications, or that

Dacies would consider those black applicants it, but only

if, a Furnco employee would “refer” their names to him.

The existence of these alleged policies was first disclosed

to plaintiffs in Furnco’s Answer and subsequent deposi

tions. The very secrecy of this ostensible policy is ciitical,

not merely because it calls into question Dacies’ good faith,

but because the information would have greatly assisted

the black jobseekers to obtain work. If plaintiffs had known

in 1971 that Dacies would have considered them had they

been “referred” to him by another Furnco employee, plain

tiffs could readily have contacted Furnco employees whom

they knew, or sought to meet one and requested such a

referral. Instead, Dacies compounded the discriminatory

practice of keeping secret, the existence of vacancies by also

keeping secret the procedure to be followed in obtaining

consideration for such a position.

Dacies’ conduct is particularly difficult to reconcile with

petitioner’s claim of non-discrimination when that conduct

13 Tr. 251-52, 521-22.

z44 Tr. 74, 7G. A similar attempt to evade black applicants was

condemned in Sellers v. 11 ilson, 123 F.Supp. 917 (M.D. Ala. 1954).

25

is compared with the instructions Dacies received from

Wright. Although Wright imposed no constraints on

Dacies method of hiring, he did direct him to hire if pos

sible enough black bricklayers to constitute “at least” 16%

of the work force. Although Dacies told Wright that he

would implement Wright’s professed desire for substan

tial minority employment by getting the names of qualified

blacks from Urbanski,13 45 * Dacies actually hired only a single

black in this manner.40 Despite the fact that Dacies’ prac

tices resulted prior to October 10 in the employment of

only 4 blacks of 41 bricklayers, less than 10%,47 compared to

Wright’s minimum goal of 16%, and despite Wright’s in

struction that the goal be reached “if possible”, Dacies

continued to refuse to consider or hire blacks whom he

knew were seeking work and whose qualifications he either

knew personally or could readily have confirmed. The stark

contrast between Wright’s goals and Dacies’ actions not

only fails to establish that Dacies was implementing a non-

discriminatory policy selected for non-discriminatory rea

sons, but compels the opposite conclusion.

There is, moreover, no claim advanced in this case that

Dacies rejected Nemhard because Nemhard was, or Dapies

believed him to be, unqualified.48 Dacies simply refused to

consider the qualifications of the blacks at the job site, or

to consider their proffered verbal or written49 applications.

45 Tr. 777.

40 See supra at p. 8, n.l l.

47 J. Alston and lt.D .Jones were merely transferred from other

Furnco job. A third black, Theodore Alston, was hired upon the

referral of bis brother. See supra at n.13. If the transferees are

disregarded, blacks constituted less only 5% of those actually hired

by Dacies prior to October 10. ' • n -

. • ‘ 1 ! ) ! I ; * i

48 Indeed, Wright admitted it was possible thfjt, t^e. bricklayers

who unsuccessfully sought work at the gate were more competent

than the bricklayer.; actually hired for the Interlake job. Tr. GS9-90.

49 See supra at p. 11.

26

While such a practice, like secret vacancies and secret hir

ing procedures, is not per se unlawful, it is necessarily sus

pect. Ordinarily the primary legitimate interest of an

employer is in hiring the host qualified workers, an interest

that is frustrated, not served, by refusing to consider the

comparative qualifications of interested job seekers. In

adopting Title VII, “ [f]ar from disparaging job qualifica

tions as such, Congress has made such qualifications the

controlling factor, so that race, religion, nationality, and

sex become irrelevant”. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424, 436 (1971). Where, as here, an employer seeks

to justify the rejection of black applicants by resort to a

criterion which was not and did not purport to be a mea

sure of their actual qualifications, the burden which the

employer must bear in proving the criterion was not

adopted or applied in a discriminatory manner is par

ticularly heavy.

The record in this case compels the conclusion that

Dacics’ refusal to hire at the gate was not a neutral, noil-

discriminatory policy common to all Furnco supervisors,

but his own improvised means of sealing off a flow of blacks

lie did not want to hire. Xot only did Furnco fail to estab

lish that the exclusion of Xemliard was the result of legiti

mate practices, fairly adopted and applied, but the uncon

tradicted evidence also demonstrated that those policies

were a mere pretext for discrimination.

2. The Statistical Defense

Furnco urges in the alternative that it adopted in 1971

a voluntary “affirmative action” plan that resulted m a

work force on the Interlake job that was approximately

13% black, and that this exceeded the proportion of blacks

27

in the area work force.2 60 61 Proceeding from this Court’s re

cent decisions on statistical evidence in Title VII cases,

Furnco contends that these statistics are conclusive proof

that there was no racial discrimination.

Although statistics may be adduced by either party in

a Title VII action, such evidence does not preclude further

factual inquiry. This Court has repeatedly held that a

disparity between an employer’s work force and that of

the labor market is evidence of intentional discrimination,

but that it is not conclusive. Even where an employer has

no minority employees, it is entitled to attempt to rebut

that weighty evidence of discrimination by proving that

the absence of minority employees was the result of noil-

discriminatory business practices adopted and applied in

a non-discriminatory manner. Hazelwood School District

v. United States, 53 L.Ed.2d 768, 77S-79 (1977); Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 339 (1977). Conversely,

where the proportion of blacks hired by an employer is

comparable to the area work force, that fact is evidence

of non-discrimination, but it is not conclusive of that issue;

a plaintiff is still entitled to an opportunity to show that

there were individual or systematic acts of discrimination.

Cf. Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. at 266, n.14 (1977).51

If an employer refuses on the basis of race to hire

blacks, it cannot subsequently cure that act of discrimina

tion by merely adopting a program which might be denoted

60 Respondents maintain that the proportion of blacks in the

area work force exceeded 13%. See infra at p. 47.

61 “If the company discriminates against a black or a woman, it

can be called to account for violating Title VII, regardless of the

percentage of blacks and women among its [employees].” Patter

son v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257, 275, n.18 (4th Cir.

1976), ccrt. denied 429 U.S. 920 (1976).

28

“affirmative action”. “The company’s later changes in its

hiring . . . could be of little comfort to the victim of the

earlier post-Act discrimination, and could not erase its

previous illegal conduct or its obligation to afford relief

to those who suffered because of it”. Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. at 341-42. Such a violation gives rise to

an obligation to provide the victims with back pay and

offers of the unlawfully withheld employment. To the ex

tent that voluntary action provides to the victims the relief

that a court would order, it reduces the employer’s liability

to suit, and such action is of course encouraged by Title

VII. But voluntary action, however denoted, which bene

fits other blacks does not place the victims in the position

which they would have occupied but for the act of dis

crimination. Similarly, an employer could not by hiring

a large number of blacks at the outset of a job acquire a

license to discriminate thereafter against other blacks.

Although statistics showing a substantial minority work

force might in some cases help to rebut a prima facie.

case, such evidence was largely irrelevant here. In light

of the detailed evidence as to the hiring practices at the

Interlake site, Furnco was called upon to adduce evidence

as to why Dacies had refused to put Smith, Samuels, or

any other black bricklayer on his list, and, more broadly,

why Dacies had refused to consider black applicants at all.

Although Furnco did employ ten black bricklayers at the

Interlake job, none of these were hired by Dacies on his

own initiative. On the contrary, Dacies only hired these,

or indeed any blacks at all, under orders from Wright.

The fact that Wright’s orders resulted in a significant

number of blacks being hired may be evidence as to

Wright’s motivation, but it tells us nothing about why

Dacies acted as he did when not carrying out those orders.

Both the four blacks employed in September and the six-'

29

blacks employed in October were hired at the insistence

of Wright. The only statistic that matters in evaluating

Dacies’ motive is the percentage of blacks he hired for

the positions which he had untrammeled freedom to fill

as he wished. That percentage is an “inexorable zero.”

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. at 342, n.23 (1977).

Even if Dacies had not been acting at the direction of

Wright, the manner in which the blacks were employed

vitiated any evidentiary value of Furnco’s statistics. Of

the ten black employees, six were referred to and hired by

Dacies because of threatened litigation.62 “Such actions

in the face of litigation are equivocal in purpose, motive,

and performance.” Jenleins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d

28, 33 (5th Cir. 1908). Of the other four blacks, two were

not hired at all, but were merely transferred from other

Furnco jobs.63 Of the remaining two blacks, one was a

brother of a transferee who was hired after being “re

ferred” by his brother.64 Although Furnco asserts that it

“went out and actively recruited and hired qualified black

bricklayers”,66 at most only a single black was ever hired

in this manner.66 Such a statistic is clearly of no eviden

tiary significance in rebutting plaintiffs’ prima facie case.

3- Petitioner insists that Wrigiit acted in good faith in asking

that Daeies hire the blacks involved in the Batiste case. Brief of

Petitioner, p. 7. But petitioner does not and could not plausibly

claim that Wright would have referred these blacks, or even known

them, had it not been for the threatened action in Batiste.

62 R.D. Jones and Joseph Alston.

64 Theodore Alston. \

65 Brief of Petitioner, p. 38.

66 Cannon. Tr. 781.

30

II.

Furnco’s Failure To Hire Nemhard Was Tlic Result

Of Unlawful Perpetuation Of Intentional Discrimina

tion.

In addition to direct acts of intentional discrimination,

Title VII prohibits the implementation of employment

policies which perpetuate the effect of prior discrimination.

“Under the Act, practices, procedures, or tests neutral on

their face, and even neutral in terms of intent, cannot be

maintained if they operate to ‘freeze’ the status quo of

prior discriminatory employment practices”. Griggs v.

Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. at 430. The record in this

case demonstrates that Daeies* policies had just such an

effect on blacks, such as Nemhard, seeking employment on

the Interlake job.

A. T he Referral System

Daeies testified that, in addition to hiring bricklayers

known to him personally, he would hire qualified brick

layers who were “referred” or nominated by a bricklayer

already employed by Furneo. (Tr. 770). This required not

that a bricklayer apply for a job and list a Furneo employee

as a reference, but that the existing employee volunteer the

applicant’s name to Daeies without waiting for an inquiry

from Daeies himself. Several bricklayers were in fact hired

in this manner for the Interlake job. (Tr. 781, 784). The

key to entry into the job via this route was personal ac

quaintance with a Furneo employee.

This system was similar to that which was held unlawful

Asbestos Workers Local 53 v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1909), and which this Court condemned in Teamsters,

431 U.S. at 349, n.32. In Asbestos Workers the union only"

31

considered for membership persons related to present

members by blood or marriage. Since, as a result of prior

pre-Act discrimination, all those members were white, the

exclusionary rule precluded minorities from “any real op

portunity for membership”. 407 F.2d at 1054. In Asbestos

Workers the minorities intentionally excluded in the past

and those who were the victims of the perpetuation were

necessarily different ; the latter were the relatives of the

former. The case illustrates how a practice can perpetuate

ami extend to one minority worker the effect of past dis

crimination against another.57 58

Daeies’ internal referral system worked in a manner

similar to that in Asbestos Workers. Hiring through this

system required that prospective employees have some

friendship or acquaintance with present Furneo employees

who would be willing to take the initiative and refer them.55

In the instant case, however, the overwhelming majority

of the workers on the Interlake job were hired off Daeies’

list and were white. Since white employees were more

likely to know and refer white friends, it is not surprising

that the whites hired by Daeies in this manner had been

proposed by whites, and that the only black thus hired

had been referred by a black. The existence and dis-

57 See also Hock v. Norfolk and Western It.It., -173 F.2d 1344,

1347 (4th Cir. 1973); Parham v. Southwestern Dcll-Tclephonc,

433 F.2d 421, 427 (8th Cir. 1970); Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co..

3ti(i F.Supp. 87, 103 (F T). Mich. 1973). tiff’d sub nom. E.E.O.C.

v. Detroit Edison, 51.7 F.2d 301, 313 (0th Cir. 1975), vac. and

remanded on other grounds 53 Tj.Fcl.2d 207 (1977).

58 This is not a situation in which the employer accepted applica

tions and required applicants to demonstrate their skill by means

of a recommendation from a company employee or other reliable

source. In such a case any applicant would have ,'at least some

opportunity to establish his qualifications. Here, even though

respondents could doubtless have established their skills in this

manner, they were not afforded a chance to do so amless a present

employee nominated them for consideration. -V • '

32

criminatory impact of intra-race referral patterns have

been recognized in a variety of other Title \ II cases. See,

e.g., United Slates v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 925-

26 (5th Cir. 1973); Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone

Co., 433 F.2d 421, 427 (8th Cir. 1979).

The application of this discriminatory system to Nem-

hard is readily apparent. Smith, as we demonstrated

earlier, was intentionally excluded by Dacies on the basis

of race from Dacies’ list and from employment at Interlake

in August of 1971. Had Smith been hired at that time, ho

would have been in a position to refer other bricklayers

whom he knew. Nemhard was just such a bricklayer. Not

only was Smith acquainted with Nemhard, it was Smith

who had told Nemhard about the Interlake job. (Tr. 74).

On several occasions Smith and Nemhard went together to

Interlake to seek work as bricklayers. (Tr. 76, 104, 330).

Instead of hiring Smith in August, nvlien the period of

substantial hiring lay ahead, Dacies did not hire Smith

until mid-October, when the job was nearing completion

and layoffs were imminent. By then it was too late for

Smith to refer anyone. There is, moreover, no indication

that Dacies, who never told the black applicants about the

insider referral rule, ever revealed it to the black brick

layers he employed either.

The record strongly suggests that Smith was rejected

in August precisely because he might have referred other

blacks. Smith testified, and Dacies did not deny, that when

Smith asked Dacies why he had been hired only toward

the end of the job, Dacies replied “if you [had gotten]

off to yourself away from the other fellows, I would have

hired you”. (Tr. 334). Nemhard, of course, was one of “the

other fellows”.

33

B. Prior Intentional D iscrim ination

Against Nem hard58

As has been discussed, Dacies primarily selected em

ployees from a list of bricklayers who had previously

worked with or for him.59 60 This list was tainted by dis

crimination not only because of Dacies’ actions in selecting

only whites from the pool of employees with whom he had

worked, but also because black bricklayers in the area, such

as Nemhard, were denied an opportunity to enter that

pool because of Furnco’s and Dacies’ earlier practice of

discriminating against black bricklayers.61

The evidence in the record, uncontradicted by Furnco,

is that Furnco employed only white superintendents in the

Chicago area62 and that until 1969, the company employed

only white bricklayers.63 Dacies’ practice of discrimina