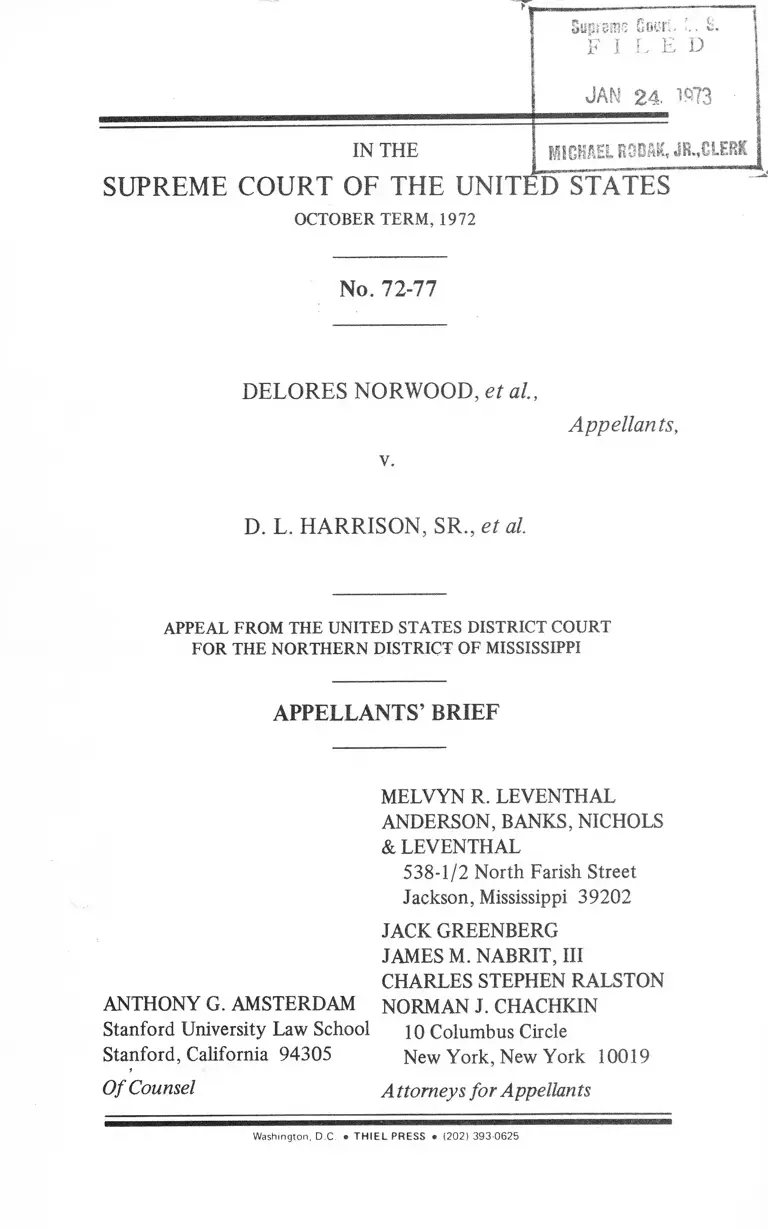

Norwood v. Harrison Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 24, 1973

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Norwood v. Harrison Appellants' Brief, 1973. f718d902-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74bcc1be-d00a-4c79-88f9-cf1993f18493/norwood-v-harrison-appellants-brief. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court, S.

F I L E D

JAN 2 4 1973

IN THE MICHAEL RDDASC, JR.,CLERK

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITEFSTATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

No. 72-77

DELORES NORWOOD, et al,

v.

Appellants,

D. L. HARRISON, SR., et al.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

APPELLANTS’ BRIEL

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Of Counsel

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

ANDERSON, BANKS, NICHOLS

& LEVENTHAL

538-1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Washington, D C. • T H IEL PR ESS • (202) 393 0625

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINION B E L O W ................ ...................................... . . . 1

JURISDICTION .......................................................................... . 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVI

SIONS INVOLVED ........... .. ................................................. 2

QUESTION PRESENTED............................................................. 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE:

I. Proceedings B e lo w ................... 3

II. The Growth of Private Academies and Their

Impact on Public Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

A. Statewide Perspective ............................................... 8

B. Impact o f Private Academies on Public

School Desegregation in Specific School

Districts .............. . 13

1. Holmes County School District ...................... 14

2. Canton Municipal Separate School District . . 15

3. Jackson Municipal Separate School D istrict. . 16

4. Amite County ..................................................... 17

5. Indianola Municipal Separate School District . 18

6. Grenada Municipal Separate School District. . 19

III. The State’s Textbook Program ....................................... 19

A. The Program Generally ............................................ 19

B. The Extent o f Textbook Aid to Private

Racially Segregated Academies ............................... 22

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 23

ARGUMENT ........... 24

CONCLUSION . . . ................. 34

APPENDIX A — Private Non-Secretarian Academies

Participating in State’s Textbook Program ....................... la

APPENDIX B - State-Wide Enrollments................................ lb

(i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Ch. 1958) ........... .. 28

Adams v. Richardson,___ F. Supp. ___(D. D. C. 1972). . 25n

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19(1969) ................... ........................... 3, 5, 9, 11

Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate School

District & Madison County School Dist., No.

28030 (5th Cir., Dec. 22, 1969) ............................... .. 28

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) . ............................... 29

Blackwell v. Anguilla Line Consolidated School Dist.,

No. 28030 (5th Cir., Nov. 24, 1969) 28

Board of Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236 (1968) . . . 8, 32, 33

Bradford v. Roberts, 175 U.S. 291 (1889) ............................... 31

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 ( 1 9 5 4 ) . . . . . . . 5, 9

Brown v. South Carolina Board of Education, 296 F.

Supp. 199 (D. S. C. 1968), affirmed per curiam,

393 U.S. 222 (1968) .............................................................. 27

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) -2 9

Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission,

296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1 9 6 9 ) ................ 11, 12, 1 4 ,2 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) . ................................. 24, 29

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................................... 9n

Everson v. Board o f Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947)................... 8

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 337 F. Supp. 22

(M.D. Ala. 1 9 7 2 ) .......................................................................... 28

Jo Ann Graham v. Evangeline Parish School Board,

C.A. No. 11053, W.D. La., July 28, 1972, appeal

pending, 5th Cir. No. 72-3033 ............................................... 24n

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D. D.C.

1971), affirmed sub nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S.

997 ( 1 9 7 1 ) .........................................., ..........................

<ii)

25, 26n

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ................. .. 3, 5, 9, 11, 24, 25

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127 (D. D.C.

1970), appeal dismissed for want o f jurisdiction,

sub nom. Cannon v. Green, 398 U.S. 956 (1970) . . 14, 25, 26

Griffin v. State Board o f Education, 239 F. Supp.

560(E .D . Va. 1965) ................................................................- 3 1

Griffin v. State Board of Education, 296 F. Supp.

1178 (E.D.Va. 1 9 6 9 ) .......................................................... 2 7 ,2 8

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 940 (1969) 9n

Jackson Municipal Separate School District v. Derek

Jerome Singleton, cert, denied, 402 U.S. 944 (1971) . . . . 17n

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, Civ.

No. 10,687 (W.D. La., Sept. 25, 1 9 7 0 ) .................................... 28

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1 9 7 1 ).............................. 31, 32

McGlotten v. Connally, 338 F.Supp. 448

(D.D.C. 1972)............................................................... ................ 30

North Carolina Board o f Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971) ..............................................................................25n

Norwood v. Harrison, 340 F. Supp. 1003 (N.D. Miss.

1972 ..................................................................... 7, 8, 21, 29

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ......................... 29, 30

Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925) ................. • • 33

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Com

mission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967),

judgment affirmed, 389 U.S. 571 (1968) ................... .. • • • 27

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 ( 1 9 6 7 ) .................................... 29

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) . .................................. 29

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) ..................................... 33

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d

959, (4th Cir., 1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S.

938 (1 9 6 3 )........................................................................................ 31

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 5 ) ...................... .. 10

Swann v. Charlotte- Mecklenburg Board o f Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..................................................... 12, 25n

Taylor v. Coahoma County School District, 345 F.

Supp. 891 (N.D. Miss. 1972) ...................... .. ................ .. 28

Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672 ( 1 9 7 1 ) . ................................. 31

United States v. Covington County School Dist.,

No. 28030 (5th Cir., Dec. 17, 1969) ........... .. ........................ 28

United States v. Hinds County School Board, 433

F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1969) ..........................................

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F.2d 836, affirmed en banc, 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) .................................... .. ............. .. -25n

United States v. Tunica County School Dist., 323

F. Supp. 1019 (N.D. Miss. 1970), a ffd , 440 F.2d

377 (5th Cir. 1971) ........... .............................................. 3n, 4n, 5

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215, affirming per

curiam, Lee v. Macon County Board of Education,

267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967) . ....................................... 27

Wright v. City of Brighton, 441 F.2d 447 (5th Cir.),

cert denied, sub nom. Hoover Academy, Inc. v.

Wright, 404 U.S. 915 (1971) ............................ .......................28

Wright v. City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) . . . . 26, 28, 30

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ................................................................................ 2

28 U.S.C. § 2101(b) .................................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. § § 2281 ,2284 .............. .. ................................... ............. 1

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l ........................................................................... 11

Emergency School Assistance Act, 1970 ........... .. ......................21n

Miss. Code, 1942, § 6656 .................................................................. 2

Miss. Code, 1942, § § 6634-6659.5 ......................... 19, 20, 21, 22

U.S. Code Congressional & Administrative News, P.L.

91-381 ,84 Stat. 806, September 5, 1970 ...............................21n

(iv)

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

No. 72-77

DELORES NORWOOD, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

D. L. HARRISON, SR., et al.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi is reported at 340

F. Supp. 1003 (N.D. Miss. 1972).

JURISDICTION

This is an appeal from a final judgment entered by a

three-judge district court, convened pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §§ 2281 and 2284, denying a permanent

injunction enjoining state officials from enforcing a state

1

2

statute having state-wide application. Jurisdiction accord

ingly vests in this Court under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

Final judgment was entered on April 18, 1972. Notice

of Appeal was filed in the district court on May 16,

1972—within 60 days from the final judgment (28 U.S.C.

§ 2101(b)).1 A jurisdictional statement was filed and the

case docketed in this Court on July 14, 1972—within 60

days from the filing of the notice of appeal (U. S.

Supreme Court Rule 13). October 10, 1972, this Court

noted probable jurisdiction.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

This case also involves § 6656 of the Mississippi Code,

1942 (volume 5, pp. 495-96 of the Mississippi Code,

1942, Chap. 152, Laws of 1940), which states:

Plan.-This act is intended to furnish a plan for the

adoption, purchase, distribution, care and use of

free textbooks to be loaned to the pupils in all

elementary and high schools of Mississippi.

The books herein provided by the board shall be

distributed and loaned free of cost to the children of

the free public schools of the state, and all other

schools located in the state, which maintain

educational standards equivalent to the standards

established by the state department of education for

the state schools.

JIn accordance with standard practice in three-judge district

court cases plaintiffs also perfected an appeal to the United States

Court o f Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

3

Teachers shall permit all pupils in all grades of

any public school to carry to their homes, for home

study, the free text books loaned to them, and to

carry to their homes, for home study, all other

regular text books used in the public schools of the

state whether they be free text books or not.

(Emphasis added.)

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Miss. Code, 1942, § 6656 to the extent that

it provides for the distribution of state owned textbooks

to private racially segregated academies formed for the

purpose and/or having the effect of providing white

students and faculty with an alternative to public

integrated schools, violates the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I.

PROCEEDINGS BELOW

January 23, 1970, the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Mississippi entered an order

requiring the integration of all public schools of Tunica

County, Mississippi, no later than February 2, 1970, in

accordance with standards established by this Court in

Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), and Alexander v. Holmes County Board

o f Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969).2 Upon the entry of

this order the parents of all white students of Tunica

2The history of public school desegregation in Tunica County is

reviewed in United States v. Tunica County School District, 323 F.

Supp. 1019, 1021-23 (N.D. Miss. 1970).

4

County withdrew their children from public schools and

formed a private academy housed in church facilities.

(Petty Deposition, p. 8.) The principal and 17 high school

teachers of the Tunica County system resigned in

mid-year to assume positions with the new private school.

(Isbell Deposition, pp. 16, 28.)

December 4, 1969, the Executive Secretary of the

Mississippi Textbook Purchasing Board, appellee herein,

had circulated a memorandum to “County and Separate

District Superintendents” which stated:

Subject: Textbooks for Private Schools.

We have many disturbed parents since the Court

decisions. Many of them are going to organize

private schools, and they are going to need books.

Since all the money has been allotted for this year,

it will be necessary for the superintendents to

transfer books with the student as he transfers to

the private school. . . .

We appreciate your cooperation in this difficult

situation. (Snowden Deposition, June 28, 1971,

Exhibit 1)

As a result of this memorandum the textbooks used by

white students fleeing integrated education in Tunica

County and throughout the state were transferred from

public schools to private segregationist academies in

January, 1970. (Floyd Deposition, pp. 16-17, S3)3

3The first challenge to the transfer of state textbooks from

public to private schools o f Tunica County was entered in United

States v. Tunica County Board o f Education, 323 F. Supp. 1019

(N.D. Miss. 1970). There, black public school children challenged

the transfer of state textbooks from Tunica public schools to the

Tunica Church School which discontinued its program and

returned all textbooks to the public schools at the conclusion of

the 1969-70 school year. The issue was, in the context of that

Mgation, moot. 323 F. Supp. at 1028. f/oomofe continued)

5

October 8, 1970, four black students of Tunica

County filed this class action to enjoin the Mississippi

Textbook Purchasing Board and its Executive Secretary

from distributing state-owned textbooks to the Tunica

Institute of Learning4 and all other academies of

Mississippi formed in response to the implementation of

this Court’s Brown, Alexander and Green decisions.5

Plaintiffs alleged, inter alia, that:

[T]heir right to a racially integrated and otherwise

non-discriminatory public school system, vindicated

by order of . . . [the district court] dated January

23, 1970 [United States and Driver v. Tunica

County School District, . . .] and their right to the

elimination of state support for racially segregated

schools, have been frustrated and/or abridged by the

creation of the racially segregated Tunica County

Institute of Learning and the policies and practices

of defendants as set forth below. . .

(footnote 3 continued)

The instant lawsuit, however, named the Tunica Institute of

Learning as the private academy of Tunica County enrolling all

white students o f the district and receiving state owned textbooks.

During the 1970-71 school year that academy held in excess of

2,000 volumes costing the State $7,000. (See Appendix A. hereto,

p. 2a).

4Tunica County public school officials continued to pay the

salaries of the white teachers and the principal who abandoned the

public schools in favor of the newly formed church academy. This

practice was enjoined and restitution ordered. United States v.

Tunica County School District, 323 F. Supp. 1019 (N.D. Miss.

1970), affirmed, 440 F.2d 377 (5th Cir. 1971).

5 Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). (Brown /);

Alexander v. Holmes County Board o f Education, 396 U.S. 19

(1969); Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968).

6

Beginning with the 1964-65 school year-when

the first school districts in Mississippi were required

to integrate under freedom of choice—and through

the present, numerous private schools and academies

have been either formed or enlarged, which schools

have established as their objective and/or have had

the effect of affording the white children of the state

of Mississippi racially segregated elementary and

secondary schools as an alternative to racially

integrated and otherwise non-discriminatory public

schools.

The defendants have provided these racially

segregated schools and academies and the students

attending such schools, . . . textbooks purchased and

owned by the State of Mississippi and have thereby

provided state aid and encouragement to racially

segregated education and have thereby impeded the

establishment of racially integrated public schools in

violation of plaintiffs’ rights assured and protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

(A. 20-21)

Appellants prayed for an order enjoining the Mississippi

Textbook Purchasing Board from any further distribution

of state owned textbooks to segregationist academies and

for an order recalling state textbooks which had already

been distributed to such institutions. (A. 21-22) After

stipulations were filed and depositions taken, appellants

refined their prayer for relief: we sought an order

withdrawing state textbook aid from 148 specifically

named all-white private academies, enrolling 42,000

students, formed or enlarged for the purpose and/or with

the effect of providing white students with an alternative

7

to public integrated education. Norwood v. Harrison, 340

F. Supp. at 1011.6

6There were 202 private schools operating in Mississippi during

the 1970-71 school year:

Number of Schools Enrollment

Private segregationist

Academies receiving

State textbooks 107 34,000

(all white)

Private segregationist

Academies eligible but

not participating in

State’s program 41 8,000

(all white)

Sub-Totals 148 42,000

Catholic Schools 47 12,100

(9,200 white

2,900 black)

Other 7 1,800

(1,000 white

800 black)

Sub-Totals 54 13,900

(10,200 white

3,700 black)

Total for all private

schools: 202 65,900

(Norwood v. Harrison, supra, 340 F. Supp. at 1011, A. 4 0 4 3 )

Appellants did not challenge textbook aid to the Catholic

School System o f the State because that system has generally not

been made available to white students fleeing integrated public

schools. In addition, we excluded the 7 academies, referred to

above as “Other,” because they were either all-black, integrated or

serving the needs o f abandoned, orphaned or retarded children.

8

April 17, 1972, the district court rendered its opinion

holding that: (a) plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate that

textbook aid was vital to the private schools, i.e., that

whites would return to public schools if only textbook

aid was withdrawn; moreover, public integrated education

was secure since 90% of the student population of the

state continued to enroll in public schools; (b) the statute

under challenge was enacted in 1940 and was hence free

of any specific intent to aid private racially segregated

academies; (c) the statute under challenge provides

textbook aid to students and not to schools; and the

state’s duty to educate all of its youth permitted the

distribution of textbooks to students attending segrega

tionist academies for the very reasons expressed by this

Court in upholding similar aid to parochial schools against

a First Amendment challenge, Board o f Education v.

Allen, 392 U.S. 236 (1968); Everson v. Board o f

Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).

II.

THE GROWTH OF PRIVATE ACADEMIES AND

THEIR IMPACT ON PUBLIC EDUCATION

A. Statewide Perspective.

The district court found that by the commencement of

the 1970-71 school year a network of 148 private

segregated academies enrolling approximately 42,000

students had been formed in the state to provide white

students with an alternative to integrated public schools.

Norwood v. Harrison, supra, 340 F. Supp. at 1011, and

footnote 5 therein. As we demonstrate below the creation

and enlargement of these academies occurred simul

taneously with major events in the desegregation of public

9

schools and frustrated the attainment of fully integrated

public schools and the promise of Brown, Green and

Alexander.

The decade immediately following Brown—1954-

1964-was marked by “Massive Resistance” and public

schools were operated on an absolutely segregated basis.

Accordingly, as late as the 1963-64 school year there was

virtually no private segregationist school system in the

State.7

In 1963, black students in Jackson, Leake County,

Biloxi and Clarksdale filed the state’s first school

desegregation suits.8 In 1964, these four districts were

required to admit black first graders into white schools

and the private segregationist academy appeared for the

first time. White Citizens’ Council School #1 and

Southside Academy opened their doors in Jackson.

Clarksdale Baptist School began an elementary program

for the first time; and St. George Day School, also of

Clarksdale, doubled its enrollment and added three grades

to its curriculum. The Leake County Academy opened

7 During the 1963-64 school year there were 17 private

non-Catholic academies enrolling 2,362 students operating in the

state. Five enrolled black students only; two were schools for

retarded, orphaned or abandoned children; one was a military

academy; two were parochial schools now operated on an

integrated basis; two operated part-time programs enrolling only 25

students. The five remaining schools enrolled only 722 students.

(A. 4 0 4 1 )

8Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District; Hudson v.

Leake County School Board; Mason v. Biloxi Municipal Separate

School District, 328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964). The early history of

school desegregation in Clarksdale is reviewed in Henry v.

Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District, 409 F.2d 682, 684

(5th Cir. 1969).

10

with a curriculum limited to first graders.9 These five

schools were the only new or enlarged private academies

operating in the state during the 1964-65 school year.10

1965-66 witnessed the implementation of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and the beginning of a concert of

effort involving the Department of Justice, Department of

Health, Education and Welfare and private litigants to

promote integrated public schools. Prodded by Singleton

v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d

729 (5th Cir. 1965), most public school districts in the

state integrated at least four grades under freedom of

choice during the 1965-66 school year. (Henderson

Deposition, Exhibit 9.) And by 1965-66, Mississippi

counted 41 private segregationist academies enrolling

3,841 white students.

9 The Leake County Academy closed after one year of

operation. It then reopened in January, 1970 upon this Court’s

order in Alexander. All of the Academy’s 333 students and 13 of

its 15 teachers had enrolled or taught in the public schools during

the first semester of the 1969-70 school year. The school is housed

in an abandoned public school building (Sheppard Deposition, pp.

5,9-13).

One witness said that the Leake County Academy might have

opened during the 1963-64 school year, one year before the public

first grade was desegregated under freedom of choice. (Sheppard

Deposition, pp. 4-5.) However, the school desegregation suit was

by then notorious. See footnote 8, above.

10The facts recorded in this paragraph are contained in the

following parts of the record: Supplement to Record entered in the

district court on August 10, 1971, Chart, Interdependence o f

Public School Desegregation and the Formation and Growth o f

Private Academies; Wright Deposition, Exhibit One, thereto;

Bounds Deposition, Exhibit 10, thereto; Sheppard Deposition, pp.

4-10; Oral Argument Exhibit Two, entered into record by order of

the district court, May 15, 1972.

11

[D]uring the 1965-66 school year twenty new

private schools . . . were added [to the twenty-one]

that had been in operation in 1964-65. In each

instance the new schools opened in public school

districts which either were under court order to

desegregate or had submitted voluntary desegre

gation plans to the United Stated Department of

Health, Education and Welfare. Coffey v. State

Educational Finance Commission, 296 F. Supp.

1389, 1391 (S.D. Miss. 1969).

Green and Alexander, implemented in Mississippi

during the 1969-70 or 1970-71 school year, signalled the

end of freedom of choice and token desegregation; all

students in Mississippi public schools were then assigned

under “terminal” plans for desegregation. 1969-70 also

witnessed the opening of 55 new private academies and

the withdrawal of 21,875 white students from public

schools. During the 1970-71 school year an additional

11,061 white students withdrew from public schools to

enroll in 31 new academies. (Appendix B hereto; A. 42)u 11

11 “Voluntary” desegregation, pursuant to directives of the

Department of HEW issued under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000d-l), proceeded at approximately the

same pace as desegregation mandated by court order. According to

Dr. Lloyd Henderson, Director, Education Division, Office for Civil

Rights, the first set of regulations promulgated upon the passage of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were distributed to all school districts

in the Nation during the 1964-65 school year. The first guidelines,

requiring the desegregation of several grades under freedom of

choice, were entered in April, 1965. In March, 1968, immediately

prior to this Court’s Green, supra, decision, HEW promulgated

guidelines requiring the formulation of plans which achieved

desegregation; freedom of choice was thereafter unacceptable

(Henderson Deposition, pp. 9-10, 20-22, Exhibit 9 thereto).

12

In summary, there were two major thrusts in the

history of public school desegregation in the state of

Mississippi. The first occurred in 1965 when freedom of

choice plans for four grades were implemented in most

school districts. The second occurred in September and

December, 1969, or by September, 1970, upon the

implementation of Green and Alexander. And the record

shows that virtually all of the 148 segregationist

academies of the State opened or substantially expanded

their enrollment or curriculum concurrently with these

two major events in public school desegregation.12 (A.

42; Appendix B, hereto.)

In almost all cases the private segregationist academies

were opened without any meaningful planning and on the

“thinnest financial basis.” Coffey v. State Educational

Finance Commission, 296 F. Supp. 1389, 1392 (S.D.

Miss. 1969). No less than 19 were opened in obsolete and

abandoned public school buildings; an additional 26 were

opened in church facilities intended for Sunday School

purposes only; seven academies were opened in private

homes or in buildings that were not constructed to house

educational facilities. Of the approximately 100 acad

emies for which information is available through

deposition, only four opened in newly constructed

facilities designed to house an educational program. (A.

44-49) Many of the schools operated without any formal

12 The Jackson Municipal Separate School District was the only

public school district in the state required to enter substantial

changes in its plan of pupil assignment upon this Court’s decision

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971).

13

budget and a few depended upon contributions rather

than tuition.13

Virtually all of the academies obtained the majority of

their teachers and administrators from the public school

systems. Virtually all rely upon opposition to desegre

gation of public schools and “white flight” for their

survival.

B. Impact of Private Academies on Public School

Desegregation in Specific School Districts.

Although the district court found that 90% of the

state’s school population continues to attend public

schools it carefully refrained from any specific finding

that private academies have not undermined public

integrated education. In fact, the state-wide retention

statistic of 90% depends upon the inclusion of many

school districts which have only a token number of black

students. In the entire “gulf coast” of Mississippi and

several of the northernmost school districts of the state,

for example, there has been less resistance to public

school desegregation.14 But in districts where public

13See, for example, Minor Depositon, p. 16; Wilson Deposition,

pp. 10, 13. There were a few private schools which were well

organized and financed but they were exceptions. For an example

of a segregationist academy with a new physical plant and a

substantial budget, see Deposition of Dillon, Administrator o f

Pillow Academy o f Greenwood, Mississippi.

14Indeed, the record shows that such districts were generally

desegregated without litigation and at least one year in advance of

compliance in other parts of the state. Biloxi Municipal Separate,

one of the districts in the original school desegregation cases of

1963-64, is 85% white and without any private academy. It

desegregated all twelve grades under freedom of choice by the

1965-6Tsthbol year although it could have easily obtained a stay

until the 1967-68 school year. (Henderson Deposition, Exhibit 11.)

14

officials have provided no leadership for desegregation

and blacks constitute a larger percentage of the student

population, the implementation of freedom of choice or

terminal plans of pupil assignment triggered the

decimation of the white public school enrollment and the

resegregation of public schools.

The following desegregation histories of specific school

districts illustrate the pattern which emerged upon

desegregation in all school districts wherein blacks

constitute a substantial segment of the student enroll

ment.

1. Holmes County School District15

In September, 1965, the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi ordered Holmes

County to desegregate grades 1-4 under freedom of

choice. Concurrently three private academies (Central

Holmes Academy, Cruger-Tchula Academy, East Holmes

Academy), limited to grades 1-4 or 1-6 and enrolling

approximately 450 students, were opened. By the close of

the 1967-68 school year, when the Holmes County

system was desegregated under freedom of choice for all

twelve grades, the private schools had expanded their

program to twelve grades and their combined enrollment

to 650 white students.

Holmes County desegregated its schools under a

terminal plan in September, 1970.16 At that moment one

15 The interdependence o f public school desegregation and the

formation and growth of private academies in Holmes County was

discussed in Coffey v. State Educational Finance

Commission, 296 F. Supp. 1389, 1391, n. 7 (S.D. Miss. 1969), and

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127, 1133 (D.C. 1970).

16Holmes County was one of three districts consolidated under

the Alexander caption which was given until September 1970 to

implement a “terminal” plan.

15

additional private school opened in the county (Four

County Academy) and all but a handfull of white

students formerly enrolled in the county’s public schools

withdrew to attend private segregationist academies.

Holmes County presently has two school systems; one

public, staffed and attended by blacks; the other private,

and staffed and attended by whites who abandoned the

public schools upon this Court’s mandate in Alexander,

The appellees treat both school systems as equals under

the state’s textbook program. (Henderson Deposition,

Exhibits 9 & 10; Chart, Interdependence of Public School

Desegreation and the Formation & Growth of Private

Academies.)

2 Canton Municipal Separate School District

The Canton Academy was opened in September, 1965

concurrently with the implementation of a freedom of

choice plan for grades 1-4 in the public school system. At

the close of the freedom of choice stage of desegregation

(1968-69), the Canton Academy enrolled 140 students in

curriculum limited to grades 1-8. On January 19, 1970, at

the precise moment public schools opened under the

terminal plan of pupil assignment mandated by this Court

in Alexander, the Canton Academy expanded to serve

grades 1-12. Its enrollment surged to 1,322, or virtually

the entire white student body of the Canton Municipal

Separate School District. At the same moment, the

academy was moved into an abandoned tent factory with

a staff of 20 white teachers who had left the public

schools and with textbooks supplied by appellees herein.

(The experience of the Tunica County system, wherein

named plaintiffs attend school, was identical to that of

Canton and Holmes County; supra, pp. 3-5).

16

3. Jackson Municipal Separate School District

Prior to the 1964-65 school year Jackson and the

surrounding Hinds County counted only three white

private academies.17 All were limited to the elementary

grades and their combined enrollment totaled 411. The

1964-65 school year witnessed the desegregation of grade

one under freedom of choice and White Citizen’s Council

School #1 and Southside Academy opened as small

elementary schools serving grades 1-4. In September,

1965, Jackson and Hinds County desegregated four

grades under freedom of choice and announced that all

twelve grades would be so desegregated by 1967-68.

During the same month White Citizen’s Council #1

expanded its program to all twelve grades and increased

its enrollment from 25 to 103 students while Southwest

Academy and First Presbyterian Day School opened for

the first time. When all twelve grades of the public system

had been desegregated in 1967-68, there were nine

segregationist academies enrolling 1,250 students oper

ating throughout Jackson and Hinds County.

Terminal plans of pupil assignment were implemented

in Jackson and Hinds County in January and September,

1970. In September, 1969, the White Citizen’s Council

operated three schools enrolling 449 students. In

January, 1970, enrollment at Council Schools rose to

2,920 and other groups opened three new academies. In

September, 1970, when further changes in the plans of

pupil assignment were implemented, the White Citizen’s

Council opened three new academies while other private

groups opened two more. By the 1970-71 school year

17St. Andrews Episcopal (integrated), Jackson Academy

(opened in 1959) and Jackson Christian. (A. 40-41)

17

there were at least 18 private academies18 enrolling over

10,000 students operating in the Jackson-Hinds County

area.19 Jackson public school officials recently explained

the impact of private academies upon their system to the

court:

For this pattern is emerging: the Courts will attempt

to achieve a percentage result on the basis of

projected enrollments; these enrollments will be

rendered inaccurate by continued loss of white

students. . . .

It is an undeniable fact that desegregation cannot be

accomplished without the presence of white

students in the public schools. Surely it is not

absolutely necessary for a community to watch

more than 40% of its white students leave the

public schools Lto attend private academies] in the

space of one year. Enrollment of white students in

the system was 20,966 in September, 1969 and

12,095 in September, 1970.20

4. Amite County

Amite County was one of the school districts

consolidated in Alexander v. Holmes County Board o f

Education, supra. In January, 1970, upon remand from

this Court, two private schools, the Amite County School

Corporation and the Pine Hills Academy opened with

1 E xam ples o f Jackson-Hinds academies receiving textbooks

are: Woodland Hills Baptist, Terry, Bearss, Flowood.

19 These 1970-71 statistics are estimates accepted by the district

court.

20 Jackson Municipal Seperate School District v. Derek Jerome

Singleton, cert, denied, 402 U.S. 944 (1971); Petition for Writ of

Certiorari, pp. 29-30.

18

enrollments of 597 and 426 white students respectively-

virtually the entire white student population of the

school district. (Henderson Deposition, Exhibit 9; Chart,

Interdependence of Public School Desegregation and

Formation and Growth of Private Academies; Nowell

Deposition, pp. 5-6; Home Deposition, p. 5.) The Amite

County Private School houses grade one in the local

Mormon Church, grades two and three in the Methodist

and Presbyterian Churches, grades four and five in the

“Old Baptist Parsonage,” and grades seven through 12 in

the Baptist Church.

5. Indianola Municipal Separate School District

Indianola Academy, serving grades 1-2 and enrolling 79

pupils, opened in September, 1965 concurrently with

integration of grades 1-4 of the public schools under

freedom of choice. As additional grades of the public

schools were desegregated the academy added grades to

its curriculum and students to its rolls so that by

September, 1969, it housed 578 students in grades 1-12.

During the first semester of the 1969-70 school year

the public school district enrolled 991 white students.

However, in February, 1970, the district was required to

implement a terminal plan of pupil assignment pursuant

to Green and Alexander; and at that precise moment all

white students and 30 white teachers of the district

withdrew to the security of the segregated Indianola

Academy. Accordingly, the Indianola Academy’s enroll

ment surged from 578 white students in December, 1969

to 1,504 such students by February 9, 1970. (Cain

Deposition, pp. 5, 9; Floyd Deposition, p. 13; Henderson

Deposition, Exhibit 9; Chart, Interdependence of Public

School Desegregation and the Growth of Private

Academies.)

19

6. Grenada Municipal Separate School District

The failure of HEW to obtain voluntary desegregation

of the Grenada public schools during the 1965-66 and

1966-67 school year resulted in the termination of all

federal financial support for this district as of September

22, 1966. However, a court order was subsequently

entered requiring freedom of choice desegregation for

grades 1-12 effective September, 1967. Enter the Kirk

Academy, in September, 1967, serving grades 1-12 and

enrolling 133 students. This academy grew to an enroll

ment of 412 white students by September of 1969, to

511 by February of 1970, and to 639 by September,

1970.

Effective March 1, 1970, the public school district was

required to implement a terminal plan of pupil

assignment. On the same day a second private academy,

Grenada Lake Academy, opened in an abandoned public

school building for 180 white students formerly enrolled

in Grenada public schools. (Jaudon Deposition, pp. 3, 5.)

The histories reviewed above are not exceptional. The

pattern—public school desegregation followed by the

withdrawal of a substantial number of white students to

private academies and the resegregation of public

schools—was repeated in school district alter school

district throughout the state.

III.

THE STATE S TEXTBOOK PROGRAM

A. T he Program G enerally

Sections 6634-6659.5 of the Miss. Code of 1942

(Appendix B, Jurisdictional Statement) provide the

framework for the selection, purchase and distribution of

20

textbooks used in the state’s schools.21 The laws were

enacted in 1940 and amended, insignificantly, in 1942,

1944, 1946, 1960 and 1966. Prior to the initiation of the

free textbook program, parents were required to purchase

textbooks (§6511). Initially the Act provided textbooks

for the elementary curriculum only; in 1942, the

legislature extended the program to high school grades

(§6658).

Sections 6634 and 6641 establish the Mississippi

Textbook Purchasing Board and assign to that agency

plenary authority over the state’s multi-faceted program.

Board members are the Governor, the State Superin

tendent of Education, and three others—who must have

served 5 years in public schools of the State—appointed

by the Governor for terms of four years. The Board

employs an Executive Secretary who serves as full-time

administrator. All members of the Board and the

Executive Secretary are appellees herein.

Textbooks may only be purchased “for use in those

courses set up in the state course of study adopted by the

State Board of Education, or courses established by

special acts of the legislature” (§6646). For each such

course of study there is a “rating committee” consisting

of educators, and other “persons competent in the

appraisal of books” appointed by the Governor and State

Superintendent of Education (§6641(d)). No textbook

may be adopted or purchased by the appellees unless it is

first approved by the responsible rating committee.

Once approved, textbooks are purchased under

contracts between appellees and publishers at a price

21 The following nine states provide free textbooks to private

schools: California, Connecticut, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska,

New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island.

21

“not . . . higher than the lowest prices at which the same

books are being sold elsewhere in the United States

(§6646(1)). The publishers are required to “maintain a

depository at a place within Mississippi to be named by

the Board [Jackson] where a stock of books sufficient to

meet all reasonable and immediate demands [is] kept”

(§6641(f)).

Appellees send to each school district (and now each

private school)22 requisition forms which list all

textbooks available free through the state. The school

district or private school completes the requisition form

and returns it to the Purchasing Board where it is

22Prior to 1970 each County Superintendent o f Education was

required to requisition textbooks for all schools, public and

private, geographically located within his county. The requisition

was then approved by the Textbook Purchasing Board and

thereafter shipment was made by the School Book Depository

directly to the consignee specified by the County Superintendent

of Education.

In 1970 Congress enacted the Emergency School Assistance Act

appropriating funds to aid school districts converting to unitary

systems. The act made it unlawful for any recipient to “engage . . .

in the gift, lease or sale of real or personal property or services to a

non-public elementary or secondary school or school system

practicing discrimination on the basis of race, color or national

origin.” P.L. 91-381, 84 Stat. 806, U.S. Code Congressional and

Administrative News, September 5, 1970, pp. 3318-3319. Public

school officials wishing to participate in this federal program were

forced to disassociate themselves from the private segregationist

academies. As a result, the Textbook Board, in 1970, established

new distribution regulations which eliminated County Superin

tendents as conduits for the distribution of textbooks to private

academies. The distribution regulations are reproduced in the

district court’s opinion, footnote 2, Appendix A, pp. 5a-6a,

Jurisdictional Statement. Norwood v. Harrison, 340 F.Supp. at

1006.

22

reviewed by the Executive Secretary. After approval, the

form is sent to the Textbook Depository in Jackson

which fills the order and ships the textbooks directly to

the school district or private school. All shipping charges

are billed to the Textbook Purchasing Board

(§ §6641(f)).

B. The Extent of Textbook Aid to Private

Racially Segregated Academies.

Appendix A hereto lists the 107 academies which

receive textbooks from the State of Mississippi and which

were found by the district court to have been “formed

throughout the state since the inception of public school

desegregation.”

During the 1970-71 school year these academies

enrolled approximately 34,000 students and held 175,-

000 volumes costing the state of Mississippi approxi

mately $490,000. The annual per pupil expenditure

for new or replacement textbooks approximates $6.00,

which will result in an annual recurring state expen

diture for these academies of approximately $207,000.

The total expenditure for textbooks by the appellee

board for the 1970-71 school year was $2,819,070

(Snowden Deposition, Exhibit 12).

The district court found that there are 8,000 students

enrolled in an additional 41 private segregationist

academies which do not, at this time, participate in the

state’s program. Accordingly, an additional $120,000 in 23

23There is, o f course, an additional recurring and significant

expenditure by the state for the shipment o f textbooks from

Jackson to private schools (§ 6 6 4 1 (l)(f), Appendix B, Juris

dictional Statement).

23

initial inventories and $50,000.00 annually thereafter is

available to private segregationist academies.24

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The provision of state owned textbooks to the private

segregated academies of Mississippi is in conflict with

appellee’s affirmative duty to promote racially integrated

public schools and constitutes significant state aid to

racial segregation in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause. Neither the absence of a specific intent by the

legislature to aid the segregationist academies nor the

absence of proof that textbook aid is vital to such

academies relieves the state of its Equal Protection

obligation not to support segregation.

The lower court’s reliance upon the distinction

between aid to the student and aid to the school,

recognized by this Court in First Amendment cases, was

improper because the standards for reviewing state aid in

the context of Fourteenth Amendment and First

Amendment challenges differ substantially.

ARGUMENT

The decision of the court below upholds the action of

the State of Mississippi in providing financial assistance to

buy textbooks for pupils attending almost 150 racially

segregated private schools which were formed to promote

evasion of public school desegregation in the State. The

court below held inapplicable prior precedents striking

24 The Executive Secretary testified that the program was not

administered strictly on a per pupil allotment basis. Rather, they

sought to provide all textbooks requested and a school could

exceed its allotment by merely filing a supplemental requisition.

24

down as unconstitutional other forms of state aid to

these same segregationist academies. It upheld the

supplying of textbooks, bought with tax money and

distributed by state officials to these segregationist

institutions, on the grounds that the state acted under a

statute which had no racial motive, that the textbook aid

was not essential to continued operation of the

segregationist academies, and that similar aid has been

held consistent with the Establishment of Religion Clause

of the First Amendment.

We believe that the first ground is legally insufficient.

The second ground is both incorrect and legally irrelevant

because the Constitution forbids all public support of

school segregation. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19

(1958). The third ground relating to the Establishment

Clause is not decisive of racial discrimination issues under

the Equal Protection Clause.25

The State of Mississippi and all of its agencies must be

guided by their “affirmative” and continuing duty to

remedy and undo the effects of past racial discrimination

and convert school systems from dual to unitary

operation. The provision of free textbooks to academies

which drain public schools of white students and faculty

and which thereby frustrate the attainment of fully

integrated public schools is inconsistent with this

paramount duty.

In Green v. County School Board o f New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 437-38, the Court was confronted

25 Relying on Judge Coleman’s opinion in this case, a district

court in Louisiana has approved state textbook and transportation

aid for the segregationist academies of that state. Jo Ann Graham,

v. Evangeline Parish School Board, Civil Action No. 11053, W.D.

La., July 28, 1972, appeal pending, 5th Cir. No. 72-3033.

25

with the very argument relied upon by the court below.

There the defendant school board asserted that its only

duty under the Equal Protection Clause was to adopt a

neutral stance and permit “every student regardless of

race . . . [to] ‘freely’ choose the school he will attend.”

The Court held that the state could not remedy its long

history of support and encouragement for racial

segregation by standing neutrally aside. Rather, state

agencies were charged with an “affirmative” duty to take

whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary

system.26

This mandate which commands appellees to align

themselves unequivocally with public integrated educa

tion was recently imposed upon the federal government

in Green v. Kennedy, 309 F.Supp. 1127 (D. D.C. 1970),

appeal dismissed for want o f jurisdiction, sub nom.

Cannon v. Green, 398 U.S. 956 (1970); and see Green v.

Connally, 330 F.Supp. 1150 (D. D.C. 1971), affirmed

sub nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 9 97 (1971 ).27 There

26In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971), the Court again relying upon the state’s duty to

formulate a meaningful remedy for past policies and practices of

segregation, upheld the use of a variety o f techniques aimed at

uprooting an entrenched dual system. In North Carolina Board o f

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971), a statute tending to

interfere with the formulation of a remedy for racial segregation

was held unconstitutional.

See also United States v. Jefferson County Board o f Education,

372 F.2d 836, 869, affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.

1967);

“The only adequate redress for a previously overt system-wide

policy of segregation directed against Negroes as a collective

entity is a system-wide policy of integration.” (Emphasis in

original)

27See also Adams v. Richardson, ___ F. Supp. ----- (D. D.C.

1972).

26

the Court was confronted with mere indirect aid to

private academies and with a neutral statute enacted

without any discriminatory motive. The Court held on

motion for preliminary injunction—28that donations to

segregationist academies of Mississippi could not be offset

against income as charitable contributions for federal

income tax purposes because:

Where there is a showing, as here, that a dual system

of segregated schools was established and main

tained in the past either under State mandate or

with substantial help from State involvement and

support, the State and the school districts are under

a present, continuing and affirmative duty to

establish a “unitary, non-racial system of public

education * * * a system without a ‘white’ school

and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools.” * * * The

Federal Government is not constitutionally free to

frustrate the only constitutionally permissible state

policy, of a unitary school system, by providing

government support for endeavors to continue

under private auspices the kind of racially segregated

dual system that the state formerly supported.

{Green v. Kennedy, 309 F.Supp. 1127 at 1137)

(Emphasis added).

The affirmative duty principle of Green, supra,

underlies the recent decisions of this Court holding that

the constitutionality of a state policy in the context of

dual school systems is measured by “whether it hinders

or furthers the process of school desegregation.” Wright

v. City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972). The same

affirmative duty principle underlies the decisions of this

Court holding unconstitutional legislation providing

28The final decision reached the same result on statutory rather

than constitutional grounds, but the decision has obvious strong

constitutional overtones. See Coit v. Green, supra.

27

tuition grants for students attending private segregated

academies. Brown v. South Carolina Board o f Education,

296 F.Supp. 199 (D. S.C. 1968), affirmed per curiam,

393 U.S. 222 (1968); Poindexter v. Louisiana Finance

Commission, 275 F.Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), affirmed

per curiam, 389 U.S. 571 (1968). See Wallace v. United

States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967), affirming Lee v. Macon

County Board o f Education, 267 F.Supp. 458, 475 (M.D.

Ala. 1967). And relying entirely upon this Court’s

decisions in Brown and Poindexter, a district court stated

the rule of law in Griffin v. State Board o f Education,

296 F.Supp. 1178, 1181 (E.D. Va. 1969):

“ [T] he validity of a tuition plan is to be tried on a

severer issue: whether the arrangement in any

measure, no matter how slight, contributes to or

permits continuance of segregated public school

education.

* * * * *

To repeat, our translation of the imprimatur placed

upon Poindexter by the final authority is that any

assist whatever by the State towards provision of a

racially segregated education, exceeds the pale of

tolerance demarked by the Constitution. In our

judgment, it follows that neither motive nor purpose

is an indispensable element of the breach. The effect

of the state’s contribution is a sufficient determi

nant. . . .” (Emphasis in original)

Under this test the Court held that the Virginia

statutes were void:

Indisputably, the State supplies the money; it comes

from the public treasury; it goes to individual

residents who may expend it for a segregated

classroom. Thus, the Virginia payments are made

available to help in giving life to an educational

forum decried by the Federal Constitution. . . .

2 8

An absolute and unequivocal prohibition is the

logical effectuation of the intendment flowing from

the recent rulings of the Supreme Court. . . .

(Griffin supra, at 1181)

The courts have similarly outlawed a variety of other

forms of public aid to private racially segregated schools.

See Wright v. City o f Brighton, 441 F.2d 447 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied sub nom. Hoover Academy, Inc. v. Wright,

404 U.S. 915 (1971); Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th

Cir. 1958); United States v. Hinds County School Board,

433 F.2d 598 (5th Cir. 1969). Accord: Blackwell v.

Anguilla Line Consolidated School Dist., No. 28030 (5th

Cir., Nov. 24, 1969) (“No abandoned school facility

under this plan, if any, shall be used for private school

purposes”); United States v. Covington County School

Dist., No. 28030 (5th Cir., Dec. 17, 1969) (“It is further

ordered that the Lincoln Elementary School facility shall

not be used, leased, or sold for private school purposes”);

Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate School Dist. &

Madison County School Dist., No. 28030 (5th Cir., Dec.

22, 1969) (rule to show cause why injunction should not

issue); Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, Civ. No.

10,687 (W.D. La., Sept. 25, 1970) (granting injunction

against use of public school athletic field for game

between two private schools; field had been leased by

Lions Club, sponsor of game); Taylor v. Coahoma County

School District, 345 F.Supp. 891 (N.D. Miss. 1972);

Gilmore v. City o f Montgomery, 337 F.Supp. 22 (M.D.

Ala. 1972).

The proper inquiry, then, is whether state textbook

aid “contributes to” or “furthers” (Griffin, supra,

Emporia, supra) public school segregation. The question

almost answers itself: textbook aid enables private

segregationist academies operating on the “thinnest

2 9

financial basis” (Coffey, supra, 296 F.Supp. 1389, 1392

(S.D. Miss. 1969)) to avoid expending sums for a vital

aspect of their educational programs; it obviously aids the

segregationist schemes to have textbooks selected,

purchased and distributed by the State. And it places the

State’s “power, property and prestige behind the . . . dis

crimination,” 0Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U.S. 715, 725 (1961)), thereby frustrating the

paramount objective of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the face of these authorities the district court has

held that, to prevail, plaintiffs must prove textbook aid

vital to segregationist academies, i.e., that whites would

return to public schools if only textbooks were

withdrawn. Norwood v. Harrison, 340 F.Supp. at 1013.

However, in neither the tuition grant nor tax exemption

case was there any evidence that whites would return to

public schools if only such benefits were terminated. In

fact, segregationist academies persisted after tuition

grants and tax exemptions were withdrawn. Accord

ingly, the district court’s standard would argue for the

restoration of tuition grants and tax benefits to the

academies of Mississippi. The absurdity of this result and

the authorities cited above are sufficient answer to the

test advanced by the district court.

Moreover, the Equal Protection inquiry is not whether

the state by withdrawing aid can destroy private racial

discrimination; rather the question is whether the state is

lending its support to racial discrimination “through any

arrangement, management, funds or property.” Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19 (1958). Palmer v. Thompson, 403

U.S. 217 (1971); Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399

(1964); Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967); Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra; Shelley v. Krae-

mer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). Judge Bazelon phrased it thusly

in holding tax benefits to segregated fraternal orders

unconstitutional:

3 0

We have no illusion that our holding today will put

an end to racial discrimination or significantly

dismantle the social and economic barriers that may

be more subtle, but are surely no less destructive.

Individuals may retain their own beliefs, however

odious or offensive. But the Supreme Court has

declared that the Constitution forbids the Govern

ment from supporting and encouraging such beliefs.

By eliminating one more of the “nonobvious

involvements of the State in private conduct” we

obey the Court’s command to quarantine racism.

(Citing Burton, supra.) McGlotten v. Connally, 338

F.Supp. 448, 462 (D. D.C. 1972).

The district court also upheld Mississippi’s textbook

statute on the grounds that the statute is neutral on its

face and devoid of any purpose to aid private

segregationist academies. But this Court has made it

abundantly clear that state legislation and policy,

especially in the field of education and in the context of

a state converting from dual to unitary operation, must

be measured by its effect rather than its purpose:

[A] n inquiry into the “dominant” motivation of

school authorities is as irrelevant as it is fruitless.

The mandate of Brown II was to desegregate schools

and we have said that “the measure of any

desegregation plan is its effectiveness.” . . . Thus, we

have focused upon the effect—not the purpose or

motivation—of a school board’s action in deter

mining whether it is a permissible method of

dismantling a dual system. The existence of a

permissible purpose cannot sustain an action that

has an impermissible effect. Wright v. Council o f the

City o f Emporia, supra, 407 U.S. 451 (1972).

(Citing Palmer, supra, 403 U.S. at 225.)

31

The district court’s holding, that aid to students (as

opposed to schools) shields the state from an Equal

Protection challenge, is transparent. “ [I]t is the right of

the State . . . to make, and not the right of the pupils,

parents or schools to take” the textbook grants which is

at issue. Griffin v. State Board o f Education, 239 F.Supp.

560, 563 (E.D. Va. 1965). All of the tuition grant

legislation provided grants directly to students and not to

schools and all such legislation has been held

unconstitutional by this Court. Although the distinction

between aid to a student and aid to a school may be

relevant in the context of aid to parochial education and

the First Amendment, it finds no support in the Equal

Protection decisions of this Court.

This Court has never confused or found interchange

able equal protection and establishment of religion

standards. Thus, a “federal construction grant to a

hospital operated by a religious order” is not

unconstitutional (Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672,

679 (1971) (opinion of the Chief Justice, citing Bradford

v. Roberts, 175 U.S. 291 (1899), but racial discrimina

tion by a hospital so constructed is unconstitutional

(Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d

959, (4th Cir., 1963), cert, denied 376 U.S. 938 (1963).

And in Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 611. f.n. 5,

671, f.n. 2, the Chief Justice, speaking for the Court, and

Mr. Justice White, both recognize that the considerations

controlling in establishment of religion cases are quite

distinct from those controlling in equal protection cases.29

29“ [I]f the evidence in any of these cases showed that any of

the involved schools restricted entry on racial or religious grounds

. . . the legislation would to that extent be unconstitutional.”

Lemon, supra, 403 U.S. at 671, f.n. 2.

3 2

Board o f Education v. Allen, supra, 392 U.S. at 245

and cognate Establishment Clause cases proceed from the

premise that “religious schools pursue two goals, religious

instruction and secular education,” and that the State

may assist the second so long as it does not thereby

become entangled in the first. The function of the

“entanglement” doctrine and the aid “to student vs.

school” distinction is to identify the line between the

two missions of a parochial school, and to keep the state

on the permissible side—the secular side—of the line. But

education and segregation are inextricably interwoven in

a school restricted to whites; and there can be no

permissible role for the State in such a school.

“Entanglement” doctrines and aid to “student vs.

school” distinctions are therefore meaningless in an Equal

Protection Clause context-as a comparison of Allen,

supra, and Lemon, supra, makes clear. The Court

distinguished textbooks from teachers in those First

Amendment cases primarily because a textbook could be

confined to its secular role but a teacher could not. A

similar distinction for Equal Protection purposes would

be inconceivable: state-paid teachers and state-paid

textbooks reserved for whites in a school that excludes

blacks both violate the Equal Protection Clause i f either

does. The rules for First Amendment cases, therefore,

cannot rationally be mirrored in racial segregation cases;

the issues are, very simply, noncomparable.

The First Amendment is designed to protect religion:

it recognizes the value of religion, as nothing in the

Constitution recognizes any value in racial discrimination.

Under the First Amendment, the State may no more

forbid parochial schools than it may establish them; and

its denial of generally available benefits to parochial

school students because they attend parochial schools

3 3

would at least trench upon, if it would not invade, Free

Exercise concerns. Cf. Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398

(1963). This consideration no doubt informs both the

reference in Allen (392 U.S., at 245-47) to Pierce v.

Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925), and Allen's

conclusion that the “line between state neutrality to

religion and state support of religion is not easy to

locate” (392 U.S. at 242).

However, while the State must tolerate religious

instruction in private educational institutions, it need not

tolerate racial discrimination by them (cf Allen, supra,

392 U.S. at 247); and a segregated school-especially one

providing whites with an alternative to public integrated

schools-unlike a religious school, can invoke no

legitimate interest that the State may even acknowledge.

Moreover, religious schools may well perform, “in

addition to their sectarian function, the task of secular

education,” (Allen, supra, 392 U.S. at 248), and thereby

“serve a ‘public purpose’.” But schools which exclude

blacks and provide a segregationist alternative to public

schools serve no public purpose that the Equal Protection

Clause allows; and an underwriting of any part of then-

segregated educational function by the State is

constitutionally forbidden.

In short, the court below was plainly wrong in holding

that the present case could be resolved by reference to

Allen and First Amendment principles.

3 4

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the opinion and judgment ot

the court below should be reversed and the case

remanded with instructions to enter an order enjoining

appellees from distributing textbooks to the private

segregated academies of Mississippi.

Respectfully submitted,

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

ANDERSON, BANKS, NICHOLS

& LEVENTHAL

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Of Counsel

la

APPENDIX A*

PRIVATE NON-SECTARIAN ACADEMIES PARTICIPATING

IN STATE’S TEXTBOOK PROGRAM1

1970-71

Name of School2

1. Adams County Christian

2. Adams County Private

3. Amite School Corporation

4. Bearss Academy

5. Beeson, J.A. Academy

6. Benton Academy

7. Bentonia Academy

8. Brandon Academy

9. Brookhaven Academy

10. Calhoun Academy

11. Canton Academy

12. Carroll Academy

13. Central Academy

14. Central Delta Academy

15. Central Holmes

16. Centreville Academy

17. Chamberlain Hunt Academy

18. Chickasaw Academy

19. Children’s Academy (The)

20. Christ Episcopal Day School

21. Citizens School

22. Claiborne Educational Foundation

23. Clarke Academy

24. Clarksdale Baptist

25. College Hill Academy

26. Columbia Academy

27. Copiah Academy

28. Covington School Foundation

29. Cruger-Tchula Academy

30. Deer Creek School

31. East Holmes Academy

32. East Lowndes Academy

33. East Rankin Academy

34. First Baptist Parochial

35. First United Methodist

36. Flowood Academy

37. Four County Academy

38. Gospel Lighthouse Crhistian

39. Gray Academy

Number of Number of

Books Cost to State Students'

3,452 $ 8,918.07 535

2,513 8,327.34 1,006

3,950 11,875.26 581

417 1.146.18 117

1.531 4,229.04 265

3.148 8,432.85 421

874 1,951.35 82

3,912 11,447.46 589

2,675 6,457.74 307

294 655.14 127

8,437 25,506.60 1,225

358 1,084.83 305

1,858 5,329.29 751

1,933 4,878.66 216

3,861 12,787.11 501

3,750 10,295.55 407

829 3,398.82 360

1,420 3,586.17 164

726 2,588.70 148

2,075 5,218.28 265

1.776 4,589.91 255

2,032 4,792.38 253

387 1,478.04 340

2,356 5,937.45 427

513 1,701.51 199

1,514 4.914.35 379

2,472 7,312.20 483

512 1,494.36 75

2,299 7,712.64 438

1,821 5,126.76 496

2,776 7,791.60 619

1,745 5,056.02 247

1,341 3,149.16 180

630 1,499.64 78

1,305 3,029.25 169

443 1,251.93 227

815 1,905.90 76

119 472.95 22

1,320 3,932.43 177

This Appendix is identical to Appendix “D” ol the Jurisdictional Statement except that schools have been

arranged in alphabetical order.

!This Appendix derives entirely from compilation filed by appellees in the District Court (entered by order

of District Court, August 9, 1971). (A. 32-37)

2The District Court found that all of the “ church schools” recorded herein are essentially non-sectarian and

were formed in response to the desegregation of public schools.

All students (and all faculty members) are white except for “ 15 Chinese, 16 Oriental, 2 Indians and 2 Latin

American" students.

2 a

40. Greenwood Private Jr. High

41. Grenada Lake Academy

42. Happy Day School

43. Heidelberg Baptist Academy

44. Heritage Academy

45. Highway Baptist School

46. Hillcrest Academy

47. Humphreys Academy

48. Indianaola Academy

49. Jackson Academy

50. Jefferson Davis Academy

51. Jesus Name Faith

52. Kemper Academy

53. Kirk Academy

54. Lawrence County Academy

55. Leake Academy

56. Live Oak Academy

57. M & L Academy

58. Magnolia Heights

59. Madison-Ridgeland Academy

60. Manchester Academy

61. Marshall Academy

62. Montgomery Carroll Academy

63. Mount Pleasant Christian Academy

64. Newton County Academy

65. North Central Miss. Schools

66. North Delta Schools, Inc.

67. North Miss. Academy

68. North Sunflower Academy

69. Northwest Academy

70. Oak Hill Academy

71. Paynes Academy

72. Parklane Academy

73. Pearl River Academy

74. Pheba Academy

75. Pillow Academy

76. Pine Hills Academy

77. Pines Academy

78. Pioneer Academy

79. Prentiss Christian Schools

80. Presbyterian Day School

81. Presbyterian Day School

82. Quitman County Educational Foundation

83. Rankin Academy

84. Saint George Episcopal

85. Saint John’s Day School

86. SanFcrd Academy

87. Scott County Christian

88. Sharkey-Issaquena Academy

89. Shaw Educational Foundation

90. Simpson Academy

91. Southwest Academy

92. Southwest Christian Academy

93. Starkville Academy

94. Sylvarena Baptist Academy

95. Terry Academy

96. Tri-County Academy

97. Tunica Institute

98. Union Private

99. Walnut Hills School

1,160 4, 288.95 330

2,523 7, 119.58 381

652 884.73 110

1,993 5, 557.50 295

1,593 4 ,029.81 350

1,304 2, 839.83 104

547 1,495.26 165

3,480 10,000.71 398

7,985 24,029.01 1,209

3,071 6, 652.56 575

1,054 3 ,701.10 356

85 170.70 44

3,849 10,654.85 432

842 3 ,061.74 639

717 2, 149.32 177

2,369 6 ,809.19 500

218 822.21 412

844 2 ,013.18 42

1,930 5, 674.80 228

448 1, 151.01 136

1,004 2, 356.92 550

1,153 3 ,012.36 600

699 1, 629.49 174

1,254 3,498.30 149

887 2 ,046.92 78

723 1, 602.87 67

1,021 3, 373.19 268

442 1,230.96 95

2,243 7, 841.28 626

1,613 4 , 347.15 239

2,348 6,739.17 450

1,288 3, 635.73 96

1,539 3, 887.01 228

660 1, 209.06 104

675 1, 636.14 133

2,453 7,802.87 1,189

1,839 5, 194.44 328

156 404.82 44

438 922.65 45

779 1,975.95 180

264 576.45 135

1,247 2 ,323.11 141

727 3 ,008.91 480

1,510 5, 302.47 284

1,340 2 ,885.54 169

1,130 2 ,465.85 184

787 2 , 277.54 136

2,235 6,325.58 320

1,051 3 , 815.35 664

1,480 4 ,443.00 905

1,266 3 ,427.89 270

1,167 2,649.12 131

564 1, 689.09 361

3,229 9 , 562.77 553

1,671 4 ,255.77 236

1,378 3 ,884.61 157

1,217 4 ,327.71 438

2,189 6 , 851.52 495

1.578 4 , 526.16 202

317 816.42 114

3 a

100. Wayne County School Foundation

101. West Marion Academy

102. Westminister Academy

103. West Panola School

104. West Tallahatchie Academy

105. Wilkinson County Christian

106. Winston Academy

107. Woodland Hills Baptist Academy

TOTALS

814 2,064.21 103

2,073 6,336.78 383

252 773.86 132

1,143 3,134.67 203

666 1,856.85 178

4,002 11,359.74 404

1,781 5,036.76 288

2,279 5,598.42 428

73,424 $490,292.39 34,532

lb

APPENDIX B 1 2

STATEWIDE ENROLLMENTS

Private

Non-Sectarian Pufo!fg

Total

Change

No. of No. of Schools Opened

Schools for First Time Change