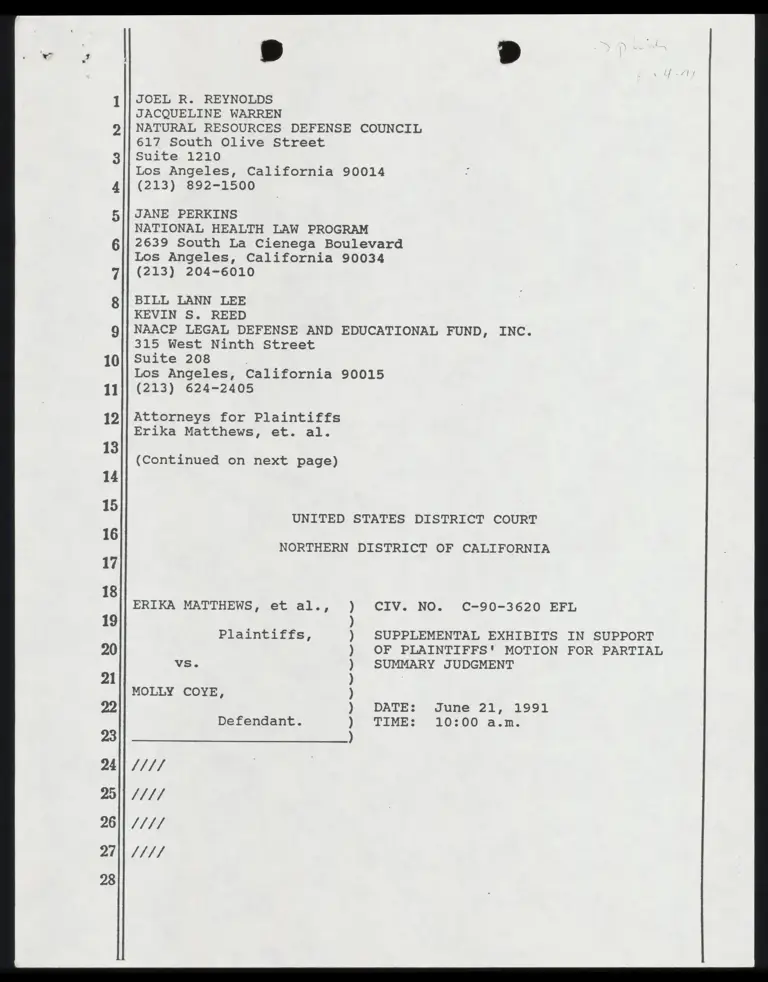

Supplemental Exhibits in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement

Public Court Documents

June 21, 1991

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Supplemental Exhibits in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement, 1991. 084ddbaf-5c40-f011-b4cb-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74e45702-426a-4439-85ec-1c3dec4b7552/supplemental-exhibits-in-support-of-plaintiffs-motion-for-partial-summary-judgement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1{{ JOEL R. REYNOLDS

JACQUELINE WARREN

2{| NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL

617 South Olive Street

3|| Suite 1210

Los Angeles, California 90014

4] (213) 892-1500

5|| JANE PERKINS

NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

6/] 2639 South La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90034

711 (213) 204-6010

g|| BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

g|| NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 West Ninth Street

10|| Suite 208

Los Angeles, California 90015

111] (213) 624-2405

12|| Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et. al.

13

(Continued on next page)

14

15

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

16

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

17

18

ERIKA MATTHEWS, et al., ) CIV. NO. C-90-3620 EFL

19 )

Plaintiffs, ) SUPPLEMENTAL EXHIBITS IN SUPPORT

20 ) OF PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR PARTIAL

vs. ) SUMMARY JUDGMENT

21 )

MOLLY COYE, )

22 ) DATE: June 21, 1991

Defendant. ). TIME: 10:00 a.m.

23 )

24(1 7/77

25{1 7/77

26) //7//

271 7/77

28

WO

00

=

~

OO

O

v

i»

WW

NN

=

DN

NO

pw

d

pk

ph

pe

d

ed

pe

d

be

d

fee

d

pe

d

ee

d

O

O

O

O

0

0

3

OH

O

v

o

W

N

=

m

OO

MARK D. ROSENBAUM

ACLU FOUNDATION OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

633 South Shatto Place

Los Angeles, California 90005

(213) 487-1720

SUSAN SPELLETICH

KIM CARD

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

1440 Broadway

Suite 700

Oakland, California 94612

(415) 451-9261

EDWARD M. CHEN

ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street

Suite 460

San Francisco, California 94103

(415) 621-2493

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et al.

////

////

////

////

////

////

[tL

/[1//

////

////

////

//1/

////

////

1/1 /

/7//

©

00

=~

OO

O

v

x

L

W

NN

m=

NN

NN

N

N

N

DN

ND

te

d

bu

d

pe

d

pe

d

ed

ed

Pee

d

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

0

3

OO

Gv

3]

N

_

LO

©

00

NI

OY

W

N

m

o

O

Exhibit X --

Exhibit Y¥ --

Exhibit 2 --

Exhibit AA --

Exhibit BB --

EXHIBITS

Declaration of Dr. Philip J. Landrigan

U.S. Congress, Office. of Technology Assistance,

Children's Dental Services Under the Medicaid

Program-Background Paper, OTA-BP-H-78 (Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 1990

H.R. Rep. No. 100-1041, lead Contamination Control

Act of 1988, reprinted in 1988 U.S. Code Cong. &

Admin. News 3793.

Supplemental Declaration of Dr. John F. Rosen

Declaration of Mark D. Rosenbaum

i o eX

DECLARATION OF DR. PHILIP J. LANDRIGAN

I, Dr. Philip. J. lLandrigan, declare and say:

1. The facts set forth herein are personally known to me

and I have first hand knowledge of them. If called as a witness,

I could and would testify competently thereto under oath.

2. I am currently Ethel H. Wise Professor and Chairman of

the Department of Community Medicine at Mount Sinai School of

Medicine of The City University of New York. Since 1985, I have

been Director of the Division of Environmental and Occupational

Medicine at Mount Sinai, where I am also a Professor in the

Department of Pediatrics. I am a Fellow of the American Academy

of Pediatrics ("Academy") and of the American College of

Epidemiology, and a member and past Chairman of the Academy's

Committee on Environmental Hazards. Since the early 1970s, I

have been actively involved in research on the epidemiology and

toxicology of pediatric exposure to lead, and I have been

involved in the clinical treatment of children with lead

poisoning since the late 1960s. (See CV Exhibit A hereto.)

3. I am familiar with the Academy's 1987 Statement on

Childhood Lead Poisoning and was directly involved in its

preparation as Chairman of the Committee on Environmental

Hazards. At the time the Statement was written, it was the

virtually unanimous sense of the Committee on Environmental

Hazards that universal lead testing of all children was required

in order to address the critical problem of childhood lead

poisoning in the United States. That sense is reflected in the

1 % .

Academy's recommendation that "ideally, all preschool children

should be screened for lead absorption by means of the

erythrocyte protoporphyrin test." The subsequent "priority

guidelines" were inserted as a practical compromise dictated by

the practitioner committee of the Academy in recognition of the

possibility of limited resources available to practitioners and

the lower risks of exposure to affluent children -- a compromise

agreed to by the Committee on Environmental Hazards only to

ensure that a statement on childhood lead poisoning would be

issued by the Academy.

4. Since that Statement was issued, scientific research has

confirmed that the effects of even low level lead exposure are

far more toxic than previously believed. On the basis of this

research, the Centers for Disease Control are preparing to

recommend that the blood lead level threshold be lowered from a

blood lead level of 25 ug/dL to a level of 10 ug/dL and that

universal blood lead testing of all children be required. These

new data from the CDC clearly confirm the medical necessity for

mandatory periodic blood lead testing of all children in order to

detect and treat excessive lead exposure in children in a timely

and effective manner. Timely detection and, if necessary,

treatment are required to prevent brain damage, learning

deficits, and other irreversible damage to the nervous system

caused by excessive exposure of children to lead.

5. Even as currently written, however, the Academy's

Statement reflects the Academy's view that periodic testing of

all preschool children is medically necessary. Particularly as

applied to Medicaid-eligible children -- virtually all of whom

exhibit one or more of the risk factors identified in the

Academy's Statement -- blood lead testing is essential, and it

would be a serious misreading of the Academy's Statement to

suggest that, in the Academy's view, such testing is not a

required element of any minimally adequate lead screening program

for all such children. To the contrary, because lead poisoning

is frequently asymptomatic in young children, periodic blood lead

testing is the only certain method to detect excessive lead

exposure. For young low income and minority children in

particular, it was unquestionably the intention of the Academy to

recommend mandatory periodic blood lead level testing.

6. It is simply nonsense to suggest that the benefits of

early lead poisoning detection by a blood lead level test are

outweighed either by the costs of the tests or the invasiveness

of the testing procedure. Not only is the drawing of blood a

common practice in a typical medical examination, but the long-

term benefits of early detection and treatment are incalculable.

Although an oral examination may perhaps be cheaper and less

invasive, it is an unreliable screening tool and inevitably will

result in lead-exposed children going undetected and untreated.

In issuing the Statement on Childhood Lead Poisoning, the

Academy's Committee on Environmental Hazards never considered

verbal screening to be even a remotely valid alternative to lead

blood tests.

, l

fw

Executed at New York, New York this /7 day of June 1991.

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is

aA

true and correct.

DR. PHILIP J. ey IGAN

June 1991

CURRICULUM VITAE

Name : Philip J. Landrigan, M.D., M.Sc., P.1.H.

Born : Boston, Massachusetts, June 14, 1942

Wife : Mary Florence

Children: Mary Frances

Christopher Paul

Elizabeth Marie

Education:

High School: Boston Latin School, 1959

College: Boston College, A.B. (magna cum laude), 1963

Medical School: Harvard - M.D., 1967

Internship: Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital, 1967-1968

Residency: Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Boston,

(Pediatrics), 1968-1970

Post Graduate: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 1976-77

Diploma of Industrial Health (England) - 1977.

Master of Science in Occupational Medicine,

University of London (with distinction) - 1977

Positions Held:

Ethel H. Wise Professor of Community Medicine and

Chairman of the Department of Community Medicine,

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1990-Present.

Director, Division of Environmental and Occupational Medicine, Department

of Community Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1985-Present.

Professor of Pediatrics, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1985-Present.

Director, Division of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations and Field Studies,

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health,

Centers for Disease Control, 1979-1985.

Chief, Environmental Hazards Activity, Cancer and Birth Defects Division,

Bureau of Epidemiology, Centers for Disease Control, 1974-1979.

Director, Research and Development, Bureau of Smallpox Eradication,

Centers for Disease Control, 1973-1974.

Epidemic Intelligence Service {E1S) Officer,

Centers for Disease Control, 1970-1973.

Philip J. Landrigan, M.D.

Adjunct Positions:

Clinical Professar of Environmental Health,

School of Public Health and Community Medicine,

University of Washington, 1983 - Present.

Visiting Lecturer on Preventive Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology,

Harvard Medical School, 1982 - Present.

Visiting Lecturer on Occupational Health,

Harvard School of Public Health, 1981 - Present.

Assistant Clinical Professor of Environmental Health,

Department of Environmental Health, College of Medicine,

University of Cincinnati, 1981 - 1986.

Visiting Fellow, TUC Institute of Occupational Health,

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 1976 - 1977.

Clinical Instructor in Pediatrics: Harvard Medical School, 1969 - 1970.

Memberships:

Fellow, American Academy of Pediatrics

Member, American Association for the Advancement of Science

Member, Society for Epidemiologic Research

Member, American Public Health Association

Elected Fellow, Royal Society of Medicine

Member, International Commission on Occupational Health, *

Scientific Committee on Epidemiology

Member, American Academy of Clinical Toxicology

Fellow, American College of Epidemiology

Member, American College of Epidemiology,

Board of Directors, 1990 - 1993.

Elected Member, American Epidemiological Society

Fellow, Collegium Ramazzini

Member, Herman Biggs Society

Fellow, New York Academy of Sciences

Member, New York Occupational Medicine Association,

Board of Directors, 1988 - 1990.

Fellow, American College of Occupational Medicine

Elected Fellow, New York Academy of Medicine

Member, The PSR Quarterly - Advisory Board

Specialty Certifications:

American Board of Pediatrics - 1973

American Board of Preventive Medicine:

General Preventive Medicine - 1979

Occupational Medicine - 1983

Philip J. landrigan, M.D.

Awards and Honors:

Department of Health, Education and Welfare - Volunteer Award - 1973

U.S. Public Health Service, Career Development Award - 1976

Centers for Disease Control, Group Citation as

Member of Beryllium Review Panel - 1978

U.S. Public Health Service, Meritorious Service Medal - 1985

Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences - 1987

Visiting Professor of the Faculty of Medicine,

University of Tokyo - September 1989

Visiting Professor of the University, University of Tokyo - July 1990

Committees:

American Academy of Pediatrics - Committee on Environmental Hazards,

1976 - Present. Chairman, 1983 - 1987.

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences,

Assembly of Life Sciences. Board on Toxicology and Environmental

Health Hazards, 1978 - 1987; Vice-Chairman, 1981 - 1984.

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Assembly of

Life Sciences, 1981-1982; Commission on Life Sciences, 1982-1984.

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, Committee for a

Planning Study for an Ongoing Study of Costs of Environment-

Related Health Effects, 1979 - 1980. .

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences, Assembly of

Life Sciences. Panel on the Proposed Air Force Study of

Herbicide Agent Orange, 1979 - 1980.

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences: Committee on

the Epidemiology of Air Pollutants, Vice-Chairman, 1984 - 1985.

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences: Committee on’

Neurotoxicology in Risk Assessment, 1987 - 1989.

National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences: Committee on

the Scientific Issues Surrounding the Regulation of Pesticides

in the Diets of Infants and Children. Chairman, 1988 - 1990.

Governor's Blue Ribbon Committee on the Love Canal, 1978 - 1979.

Harvard School of Public Health, Occupational Health Program,

Residency Review Committee, 1981 - 1983; Chairman, 1981.

World Health Organization. Contributor to the WHO Publication:

Guidelines on Studies in Environmental Epidemiology

(Environmental Health Criteria, No. 27), 1834.

International Agency for Research on Cancer, Working Groups on Cancer

Assessment, October 1981 and June 1986.

(IARC Monographs No. 29 and No. 42).

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Third Task Force

for Research Planning in the Environmental Health Sciences.

Chairman, Subtask Force on Research Strategies for Prevention

of and Intervention in Environmentally Produced Disease, 1983-1984.

National Institutes of Health, Study Section on Epidemiology and

Disease Control, 1986 - 1990.

3

Philip J. Landrigan, M.D.

Committees (continued):

Association of University Programs in Occupational Health and Safety,

1985 - Present. President, 1986 - 1988.

New York Lung Association: Research and Scientific Advisory Committee,

; 1986 - 1989. Board of Directors, 1987 - 1990.

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Clinical Research Center Advisory

Committee, 1986 - Present.

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Clinical Research Center,

Acting Program Director, 1987 - 1988;

Associate Program Director, 1987 - Present.

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Executive Faculty, 1988 - Present.

Milbank Memorial Foundation: Technical Board, 1986 - 1988.

State of New Jersey, Meadowlands Cancer Advisory Board,

Chair, 1987 - 1989.

State of New York, Asbestos Licensing Advisory Board,

Chair, 1987 - Present.

New York Academy of Medicine, Working Group on Housing and Health,

1987 - 1989, Chair, 1989.

Centers for Disease Control, Alumni Association of the Epidemic

Intelligence Service, 1972 - Present. President, 1988 - 1990.

Editorial Boards:

Consulting Editor: American Journal of Industrial Medicine, .

1979 - Present. :

Associate Section Editor for Environmental Epidemiology:

Journal of Environmental Pathology and Toxicology, 1980 - Present.

Consulting Editor: Archives of Environmental Health, 1982 - Present.

Editorial Board: Annual Review of Public Health, 1984 - Present.

Senior Editor: Environmental Research, 1985 - 1987.

Editor-in-Chief: Environmental Research, 1987 - Present.

Editorial Board: American Journal of Public Health, 1987 - Present.

Editorial Board: New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and

Occupational Health Policy, 1990 - Present.

Editorial Board: The PSR Quarterly: A Journal of Medicine

and Global Survival. 1990 - Present.

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES OFFICE OF TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT

EE re

CHILDREN’S DENTAL

SERVICES UNDER THE

MEDICAID PROGRAM

P

W

G

O

P

9

S

P

O

R

e

y

S

O

O

=

September 1990

00

D

e

w

e

e

0

4

-

0

W

v

e

3

A

E

D

E

I

D

E

I

D

W

e

d

,

a

t

t

,

'

7

FJ

Background Paper

pa

t

ad

Ri

a

E

a

f

e

F

od

y

PA

N

UN

AR

TR

L

A

0

— ” ae i a ——————— -———_ TT ST AT NS We I 8 — C3 Ae a Yr rT a

KJ

Chapter 3—Medicaid and the EPSDT Programs e 15

Nationally, less than half the children under age 13

living in poverty were covered by Medicaid for any

medical or dental services in 1986 (12).

Services

States are required to provide certain services to

categorically needy people and are allowed to

provide certain optional services’ under the Medi-

caid program. Although they are not required to do

so, most States who cover medically needy people

provide them with the same range of benefits offered

to categorically needy people in their State. States

may also impose limitations on any of the services

offered, generally to reduce unnecessary use and

control Medicaid outlays. See chapter 4 for further

discussion on the relevance of service limitations to

this study.

Reimbursement Policies

Except for a few instances,5 States generally

design their own payment methodologies and de-

velop payment levels for covered services. The only

* two universal reimbursement rules are that Medicaid

providers must accept payment in full and that

Medicaid is the ‘ ‘payer of last resort’ (i.e., Medicaid

pays only after any other payment source has been

exhausted).

Institutions, such as hospitals and long-term care

facilities, are paid differently than individual practi-

tioners. Payments to institutions are usually based

on either retrospective’ or prospective? methodol-

ogy. Individual practitioners are usually paid in one

of two ways: the lesser of their usual charge and the

State-allowed maximum, or based on a fixed fee

schedule. Reimbursement policies affect the access

of low-income children to dental care, as discussed

In chapter 4.

The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis,

and Treatment Program (EPSDT)

The EPSDT program was legislated in 1967, and

implemented in 1972.° The program is unique in that

it provides for comprehensive health care, including

preventive services, to children under Medicaid. The

five basic components of the program ensure its

comprehensiveness: informing, screening, diagno-

sis and treatment, accountability, and timeliness.

EPSDT is jointly administered and funded by

Federal and State Governments primarily through

the Medicaid program, although some States admin-

ister the programs separately.

The EPSDT program is structured on a case

management approach, to ensure comprehensive-

ness and continuity of care, though specific combi-

nations of services and providers vary by State. In

addition, since 1985 States have been allowed to pay

a ‘‘continuing care provider’’ to manage the care of

EPSDT children. This means that this provider or

provider group is responsible for ensuring that each

child receives his or her entitled services. These

entitled services include notifying the child about

periodic screens and performing, or referring, appro-

priate services, as well as maintaining the child’s

medical records.

Informing

States must inform all Medicaid eligibles, gener-

ally within 60 days of eligibility determination, of

the EPSDT program and its benefits, particularly:

e about the benefits of preventive health care;

e about the services available under EPSDT,

where and how to obtain them;

eo that the services are without cost to those under

age 18 (or up to 21, agency choice) except for

any enrollment fee, premium, or other charge

imposed on medically needy recipients; and

“States are required to provide: inpatient and outpatient hospital services, physician services, EPSDT for children under age 21, family planning

services and supplies, laboratory and x-ray procedures, skilled nursing facilities for persons over 21, home health care services for those entitled to skilled

nrsing care, rural health clinic services, and nurse midwife services (12). The EPSDT program includes dental services for children under 21.

3 S tates have the option of also providing these services: clinic services, including dental care; drugs; intermediate care facilities; eyeglasses; skilled

nursing facilities for those under age 21; rehabilitative services; prosthetic devices; private duty nursing; inpatient psychiatric care for children or the

elderly; and physical, occupational, and speech therapies (12).

Payment rules and limits are established by law for rural health clinics, hospices, and laboratories.

TA retrospective system is based on the actual cost of providing the services rendered, after they are provided.

*A prospective system is based on a predetermined rate for defined units of service, regardless of the actual cost of providing the service.

fegulations became effective on Feb. 7, 1972.

4 Periodic. The Social Security Amendments of 1967 (Public Law 90-248) added the EPSDT benefit and required implementation by July 1, 1969. Final

16 e Children’s Dental Services Under the Medicaid Program

e that transportation and scheduling assistance

are available on request.

Most States provide the information at the time of

application for welfare, though some States employ

additional outreach methods.

Screening

The program also requires that all eligible chil-

dren who request EPSDT services receive an initial

health assessment. Generally, the screening should

be performed within 6 months of the request for

EPSDT services. This screening service should

include:

e a health and development history screening,

including immunizations;

¢ unclothed physical examination;

e vision testing;

¢ hearing testing;

e laboratory tests, such as an anemia test, sickle

cell test, tuberculin test, and lead toxicity

screening; and

e direct referral to a dentist for a dental screening.

Periodic medical examinations are based on the

periodicity schedule recommended by the American

Academy of Pediatrics. The recent Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act of 1989 (Public Law 101-239)

specified that, among older children, dental exami-

nations should occur with greater frequency than is

the case with physical examinations.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Further diagnosis of conditions indicated in exams

and their treatment are also components of the

EPSDT program. Specific diagnostic and treatment

services should be part of a State’s benefit package,

though States may provide a range of services to

children enrolled in EPSDT that go beyond the

scope of benefits for other Medicaid beneficiaries.

Accountability

States are required to prepare quarterly reports

which must contain utilization data by two age

groups, 0 to 6 and 6 to 21: :

¢ number eligible for EPSDT;

¢ number of eligibles enrolled in continuing care

arrangements (and of these, the number receiv-

ing services and the number not receiving

services);

¢ number of initial and periodic examinations;

and

e number of examinations where at least one

referrable condition was identified.

Initially, the Federal Government enforced the

EPSDT provisions by imposing a monetary penalty,

a 1-percent reduction in AFDC payments, on States

not informing or providing care to eligible children

(see the Social Security Amendments of 1972

(Public Law 92-603)). This penalty was eliminated

in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981

(Public Law 97-35) and, instead, the adherence to

the EPSDT provisions became a condition of

Federal funding for Medicaid. OTA was unable to

find any evidence that any State was penalized

before 1981 or that any State has lost Medicaid

Federal funding since that time as a result of not

complying with the EPSDT provisions.

JRY

649

1R. 418 THE

UTHORIZATIONS cok ON (NSF)

otentia] uen

id subsequently i esearch vessel with joe,

qd With an option t,

located In the Unj

meritorious (that is, to

<3 Into US. jobs), the

Ties when bidd; 2s

e goals of the Fou A is

pete internationa]) 1

‘ompanies who would ' contract retribution

erica” provision cop.

Df Partners as a vio-

o a ie reverse

Y damagin

t of the retribution

Committee to 1

@ can bid ar feos

n effort to hold the

1 House, we recom.

mpact of in =

tions fo the GATT

ma crucial

with this Provan sess the impact on

iken by this provi-

R.

R.

UGHTER, Jr.

H.

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT OF 1988 ©

P.L 100-572, see page 102 Stat. 2884 ~ =

DATES OF CONSIDERATION AND PASSAGE

House: October 5, 1988

Senate: October 14, 1988

House Report (Energy and Commerce Committee) No. 100-1041,

Oct. 3, 1988 [To accompany H.R. 4939]

Cong. Record Vol. 134 (1988)

No Senate Report was submitted with this legislation.

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

[page 1)

The Committee on Energy and Commerce, to whom was referred

the bill (H.R. 4939) to amend the Safe Drinking Water Act to con-

trol lead in drinking water, having considered the same, report fa- vorably thereon with an amendment and recommend that the bill

as amended do pass. :

J J [J J [ J]

[page 5)

J $ : [J [J]

PURPOSE AND SUMMARY

This legislation provides programs intended to help reduce lead contamination in drinking water, especially for children. Its major provisions include a mandate for the Consumer Product Safety Commission to recall drinking water coolers with lead-lined water reservoir tanks; a ban on the manufacture or sale of drinking water coolers that are not lead free; a Federal program to help schools evaluate and respond to lead contamination problems, in- cluding Federal technical and financial assistance; and a lead

[page 6]

screening program for children to be administered by the Centers for Disease Control.

BACKGROUND AND NEED FOR THE LEGISLATION

The EPA estimates that 42 million Americans have tap water that contains more lead than permissible under the proposed EPA drinking water standard of 20 parts per billion (ppb), then under consideration at the Agency. (EPA has since moved to a standard

3793

ne

A

e

3

{

]

R

R

O

Sv

P

o

SH

OP

S

S

R

I

LE

T

I

OT

DM

a

S

A

N

L

Af

fe

PT

P

L

R

,

5

+

E

I

A

I

M

I

T

E

A

A

P

A

AL

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

of 5 ppb.) ! Included in this figure are 3.8 million children under

age 6.

Children are especially vulnerable to lead exposure. Experts ex-

plain that their developing nervous system is particularly sensitive.

Also, they commonly have nutrient deficiencies that cause them to

absorb and retain more lead than adults. In a 1979 study, one of

the Nation's leading experts, Herbert Needleman of the University

of Pittsburgh, found that such characteristics as reduced 1.Q.

scores, lower academic achievement, reduced language skills and

reduced attention span were associated with levels of lead in the

blood that were once considered too low to affect health.2

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

every year more than 241,000 children under age 6 are exposed to

lead in drinking water at levels high enough to impair their intel

lectual development.® The National Health and Nutrition Survey,

published in 1982, found that 9.1 percent of America’s preschool

children—a total of 1.5 million children under age 6—have lead

levels that meet the U.S. Centers for Disease Control's (CDC) defi-

nition of acute lead poisoning.

A 1986 EPA study lists the health problems that could be avoid-

ed if lead levels in tap water were reduced to the level of the pro-

posed standard then under consideration (20 parts per billion).

The study finds that in addition to the 241,000 children at risk of

mental impairment, each year some 680,000 expectant mothers in

the United States are exposed to lead levels in drinking water high

enough to be associated with miscarriage, low birth weight and re-

tarded growth and development of the fetus.$

The EPA also concludes that some 82,000 children each year are

at risk of growth impairment, and another 82,000 are at risk of ef-

fects on their blood cell formation. Nor are adult males free of risk.

EPA estimates that 130,000 cases of hypertension yearly can be as-

sociated with current drinking water lead levels, as well as a

number of heart attacks and strokes.®

! United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Reducing Lead in Drinking Water: A Ben-

efit Analysis,” (1986), p. 8.

? H. Needleman, C. Gunnoe, A. Eviton, R. Reed, H. Perisie, C. Maher and P. Barrett, “Deficits

in Psychological and Classroom Performance of Children with Elevated Dentine Lead Levels,”

New England Journal of Medicine, 300 (1979), 689-675.

? United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Reducing Lead in Drinking Water: A Ben-

efit Analysis” (1986), p. 24.

* Ibid.

$ Ibid. p. 19.

® Ibid. p. 24.

[page 7)

SOURCES OF LEAD

There are a number of other important sources of exposure to

lead in addition to drinking water. In gasoline, the use of lead has

been reduced, but not eliminated. Hence, automobile exhaust con-

tinues to release lead into our air supply and deposit it in the soil

and surface areas around the Nation's roadways. Leaded paint in

older buildings is a continuing threat to small children who might

put paint chips in their mouths.

3794

pg ——

AR

Sh

a r

o

ae

a

a

a

Ba

al

sh

alt

a

f

e

e

a

0

LEAI

But the threat f

severe and almost

sources of lead in

in drinking water

into the water su]

sive water.

L

An important

brought to light a

mittee on Health

drinking water. A’

Service report to

that some electric

or lead-lined wate

tribute.”

The Public Hea

coolers at a U.S.

authors by the U.

nation from some

lead standard the

problem was rep:

lined water tanks

In an effort to «

tamination probl«

ronment Subcom:

and requested in!

Subcommittee als

the manufacture

water comes in ¢

tanks.

The manufactu

Guiry. They provi

Marnufactu

lion water co

hundreds of 1

dreds of thou

ious, Relvinc

Thre2 ma’

used in at le

? Testiraony of Dr Pa

the Health ard Eaviror.

Congress, 1st Session, (LC

Halsey Ta

merous mod

and the last

1; S3/5/10 C

1; HWC1/H

and 8880 FT

ldren under

Experts ex-

ly sensitive.

use them to

t University

their intel-

ion Survey,

3 preschool

-have lead

(CDC) defi-

1 be avoid-

of the pro-

r billion).+

at risk of

nothers in

vater high

ht and re-

1 year are

risk of ef-

ee of risk.

can be as-

well as a

Nater: A Ben-

rett, “Deficits

Lead Levels,”

Vater: A Ben-

osure to

lead has

ust con-

the soil

paint in

0 might

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572 :

But the threat from drinking water stands out as a particularly

severe and almost wholly uncontrolled part of the problem. The

sources of lead in tap water are mainly lead pipes and lead solder

in drinking water lines and home plumbing, which release lead

into the water supply, especially in areas with particularly corro-

sive water. A

LEAD IN DRINKING WATER COOLERS

An important new lead contamination source was recently

brought to light at the December 10, 1987 hearing of the Subcom-

mittee on Health and the Environment on lead contamination of

drinking water. At the hearing, the authors of a U.S. Public Health

Service report to Congress on Childhood Lead Poisoning warned

that some electric drinking water coolers may contain lead solder

or lead-lined water tanks that release lead into the water they dis-

tribute.”

The Public Health Service warning is based on a study of water

coolers at a U.S. Navy facility. Data were supplied to the report's

authors by the U.S. EPA’s Office of Drinking Water. Lead contami-

nation from some coolers was found at levels up to 40 times the

lead standard then under consideration at EPA. The source of the

problem was reported to be lead solder and in some cases, lead-

lined water tanks used inside the water coolers.

In an effort to determine which water coolers have potential con-

tamination problems and which do not, the Health and the Envi-

ronment Subcommittee surveyed each of the major manufacturers

and requested information on the use of lead in their coolers, The

Subcommittee also asked their cooperation in immediately halting

iT

i

it

¢ A

L

a

n

b

d

r

Li

lo

a

A

A

1

e

a

n

a

rp

nn

ih

Se

r

1)

w

te

ms

o

iy

ue

-

fy

E

h

e

wt

S

E

pe

~

Ma

e

EY

a

rio

d

ri

—

-“

UBL

+ i

on

the manufacture and sale of any water coolers where the drinking 4 3 water comes in contact with lead solder, or is stored in lead-lined Ex

The manufacturers cooperated fully with the Subcommittee in- i 14 quiry. They provided the following information: Ages Manufacturers’ submissions indicated that close to one mil- REL lion water coolers now in use contain lead. This figure includes 3 5 hundreds of thousands of Halsey Taylor water coolers and hun- EE § dreds of thousands of EBCO (also sold under the names Aquar- Ag ious, Kelvinctor and Oasis) water coolers. ‘FE Threz major marufacturers indicated that lead had been 4 bo used in at least some models of their drinking water coolers. i |

1 F ? Testiaony of Dr Paul MushaX, Hearing on Lead Contamination in Drinking Water, Before : KY 3 the Health ard Environinent Subcomm.ittee of the Committee ci Energy and Commerce, 12th 33 Congress, 1st Session, tDec. 10, 1988, ir. press.

A

: - 38: SA [page 8] ; hj Ha Halsey Taylor Company reported use of lead solder in nu- $1 i merous models of water coolers manufactured between 1978 BY 1 i and the last weeks of 1987. (Including models: WMA-1; SWA- tits I; S3/5/10 C&D; S300/500/1000D; SCWT/SCWT -A; DC/DHC- Bf hs 1; HWC7/HWCT7-D; BFC-4F/F4FS/TFS; 5656 FTN; S5800FTN; EEF and 8880 FTN) Ee So

Le

2.8 An >

3795 $3

: 3 2

NE

EE

rr Tr resresrereeprpeger t= Anat Fra tea die Ming tate A WATE Dn ne I A SS WE Rel nN 2 2M 1 TAI LTR

oh

ie

on

R

e

y

E

C

P

o

Pr

Te

E

Y

=

e

vey

R

I

L

R

E

E

JE

vl dma het A TH

S

O

A

4

N

S

E

o

w

T

e

ME

S

A

T

,

- “

a

t

v

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

EBCO Manufacturing Company (whose products are also marketed under the names “Oasis , “Kelvinator,” and “Aquar- ious,”) reported the use of lead/tin solder (50 percent lead) in the bubbler valve seal in all pressure bubble coolers manufac- tured between 1962 and 1981.

A third major supplier, the Sunroc Corporation, reported the use of lead solder as a secondary seal in a limited number of bottled water coolers manufactured prior to 1983. Because of greatly reduced contact with drinking water, lead solder in a secondary seal would be expected to release less lead into the drinking water than lead solder in a primary seal. (Models USB-1, USB-3, T6Size 3, BC and BCH.)

One major supplier, Elkay Manufacturing Company, report- ed never having used lead in any of their drinking water cool- ers. Elkay coolers are also sold under the names ‘“Temprite” and “Cordley.” In addition, the Filtrine Manufacturing Compa- ny, a smaller supplier, also reported never having used lead in sny of their coolers.

nly very limited information was provided concerning water coolers manufactured prior to the 1960's, The industry has existed since before the 1520's,

The most serious problems are believed to be associated with water coolers that have water reservoir tanks that are lined with lead. In response to the Subcommittee inquiry, all of the manufac-

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY,

Washington, DC, June 21, 1988. Mr. DoyLE RAYMER,

Director, Research and Development,

Halsey Taylor, Freeport, IL.

DEAR MR. RAYMER: This letter is in reply to your correspondence dated June 10, 1988 and a follow-up to your telephone conversation with Mr. Peter Lassovszky of my staff, on May 31, 1988. At that time, Mr. Lassovszky provided you with an update of the Environ-

[page 9]

mental Protection Agency's (EPA) progress of identifying the pres- ence of lead solder-lined water tanks in 22 water coolers the Navy provided to the EPA.

Twelve of the water coolers included in this lot were manufac- tured by Halsey Taylor. EPA’s Water Engineering Rrsearch Labo-

3796

BARA

e

b

0

R

S

E

ratory (WEI

coolers man

voir tanks. /

reservoir ta

excess of 20

WERL ide

lined reserv(

Halsey Tay

Model Nun

WTS8A

WT 8A

GC10ACR

GC-10-A

GC 10A

GC 10A

The rema’

were missin

lowing iden!

5.

As reques

with the fol

1. The dat

None of the

in the list

assume that

2. The nu:

3. i

in the late

manufactur

notice.

4. Please

lead solders

tured by Hs

5. Please :

coolers havi

pany.

6. I unde

ment parts

vide inform:

I apprecis

looking for

contact Mr.

———————

120 mill;

liter.

,

a

i

-

—

P

a

BE

a

S

r

n

a

products are also

ator,” and “Aquar-

30 percent lead) in

e coolers manufac-

ation, reported the

limited number of

)» 1983. Because of

r, lead solder in a

less lead into the

ary seal. (Models

Company, report.

inking water cool-

1ames “Temprite”

ifacturing Compa-

aving used lead in

vided concerning

0's. The industry

e associated with

at are lined with

1 of the manufac-

ad tanks,

r of EPA’s Drink-

coolers tested by

»und to have lead

Subcommittee in

manufactured a

sus public health

coolers found to

e associated with

amount allowed

The EPA letter,

y Taylor coolers

-

N AGENCY,

June 21, 1988.

~

* correspondence

ne conversation

1, 1988. At that

of the Environ-

tifying the pres

s00lers the Navy

: were manufac-

Research Labo-

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572

ratory (WERL) examined these coolers and found that eight of the

coolers manufactured by Halsey Taylor had lead solder-lined reser-

voir tanks. Analysis of water samples in contact with one of these

reservoir tanks overnight revealed lead concentration levels in

excess of 20 milligrams per liter.?

WERL identified the following water coolers to have lead solder

lined reservoir tanks: :

Halsey Taylor ji

Model Number Serial number

WT SA 66 421303

WTS A 66 421268

GC10ACR 65 361559

GC-10-A 69-598593

GC 10A 142378

GC 10A 113383

The remaining two water coolers manufactured by Halsey Taylor

were missing identification tags. However, one of them had the fol-

lowing identification number on its compressor: 65643364 BM 2565

5.

As requested by Mr. Lassovezky, would you please provide me

with the following information:

1. The date of the manufacture of the water coolers listed above.

None of the model numbers identifying these coolers were included

in the list you provided to Congressman Waxman’s office, so I

assume that they may have been manufactured before 1978.

2. The number of units of each type of cooler manufactured.

3. During previous meetings with EPA staff, you indicated that

in the late 1970’s you voluntarily recalled coolers as a result of

manufacturing malfunction. Please forward a copy of this recall

notice.

4. Please forward copies of any reports dealing with the use of

lead solders in the manufacture of certain water coolers manufac-

tured by Halsey Taylor.

5. Please identify and provide information about any other water

coolers having lead solder-lined tanks manufactured by your com-

pany.

6. I understand that Halsey Taylor provides lead-free replace-

ment parts for coolers containing lead solder coolers. Please pro-

vide information about these retrofit units.

I appreciate your cooperation regarding these requests and I am

looking forward to your reply. If you have any questions please

contact Mr. Peter Lassovszky at 202 475-8499.

8 ' 20 milligrams/liter equals 2000 micrograms/liter. Proposed EPA standard is 5 micrograms/

iter.

\

h

a

t

e

ed

i

am

u

g

x1

Sh

it

RR

R:

Mv

rte

gr

of.

ip

o

d

e

h

cha

udh

i

c

LUE

B

E

GE

G

T

I

F

R

N

O

E

A

R

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

[page 10]

I will contact Mr. Thomas Sorg of WERL, to make suitable ar-

rangements to have portions of Xe reservoir tanks removed from

Halsey Taylor water coolers available to you.

Sincerely,

MicHAEL B. COoK,

Director, Office of Drinking Water.

LEAD CONTAMINATION IN SCHOOL DRINKING WATER

The discovery of lead in water coolers is especially disturbing be-

cause of the widespread use of water coolers in the Nation's

schools. Unfortunately, many of the water coolers currently in use

at our schools and offices go back to well before the early 1980's,

when all but one manufacturer halted the use of lead. In fact,

many school water coolers date back to well before 1960, an era

sho which we have little information regarding the use of lead in

coolers.

There may be a serious problem with lead contamination of

drinking water at man schools. A July 1986 survey of school

water coolers by the Maryland Department of Education found

that 67 percent of the schools surveyed had lead levels above the

EPA standard of 20 parts per billion (ppb) then under consideration

(the Agency has since proposed a level of 5 ppb). A similar survey

in Minnesota found lead at levels above 20 ppb in 40 percent of

their samples. Other surveys have found high levels of lead con-

tamination at schools in California, North Carolina, New Jersey

and New Hampshire. More exhaustive surveys are now underway

in these and several other States.

The Public Health Service report on childhood lead poisoning ex-

plains why high levels may be expected to be a particularly serious

problem in school drinking water.

1. Water-use patterns in schools (school periods, weekends, vaca-

tions) involve long standing times of water in these units, which

rmit leaching.

2. Both water cooler-fountains and building plumbing may have

lead-soldered joints and other sites of leachable lead, such as lead-

containing surfaces in cooling tanks or loose solder fragments in

pipes.

3_ Unlike the case with lead-containing plumbing in private resi-

dences, which affects only the occupants, a single ho conteining

cooler-fountain could expose a large number of users.®

FEDERAL LEAD POISONING PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Regardless of its source, lead poisoning in infants and children

has become a major public health problem, especially in inner-city

neighborhoods. Left undetected and untreated, it can cause severé

disability, including mental retardation, behavioral difficulties, and

learning disorders.

In response to this concern, Congress enacted the Lead-Based

Paint Poisoning Prevention Act (P.L. 91-695) in 1971 to establish

programs designed to test and treat children with elevated blood

8 US. Public Health Service, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, The Nature

and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress, Volume L

July 1988, p. VI-12.

3798

lead levels anc

ing. That

in areas of gre

the highest ris.

its final year ¢

based projects

Of these, 22,00

Despite this

incorporated i

Grant (Title V

other public L

about the use

there have bet

have been gre:

Lead-Based Pe

MCH Block G:

(GAO) study ¢

that lead scree

emphasis.” Ar

tion in Maten

lead poisoning

With the pu

Nature and FE

States: A Rep

poisoning prol

dren—one ou

levels. Most of

cause of struc

on various pi

effort designe

sive public bh

making impor

The Commi

held 1 day of

Safe Drinki

lative hearing

ceived from 1

tional materi:

The Healt}

problem of le

effectiveness (

1982 (Ser. Nc

including a

Human Sod

On August

ment met in

as amended,

met in open

amendment }

Y

M1

» to make suitable ar.

r tanks removed from

ICHAEL B. Cook,

e of Drinking Water.

NKING WATER

pecially disturbing be-

Jlers in the Nation's

olers currently in use

fore the early 1980's,

use of lead. In fact,

1 before 1960, an era

ling the use of lead in

ad contamination of

986 survey of school

: of Education found

lead levels above the

n under consideration

Pb). A similar survey

ped in 40 percent of

th levels of lead con-

sarolina, New Jersey

7/8 are now underway

od lead poisoning ex-

a particularly serious

iods, weekends, vaca-

n these units, which

plumbing may have

le lead, such as lead-

solder fragments in

nbing in private resi-

ingle lead-containing

"users.®

PROGRAMS

infants and children

pecially in inner-city

, 1t can cause severe

ioral difficulties, and

sted the Lead-Based

in 1971 to establish

with elevated blood

disease Registry, The Nature

teport to Congress, Volume I,

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572

[page 11] 3

lead levels and to eliminate the causes of lead-based paint poison-

ing. That program was very successful in targeting grant projects

in areas of greatest need and in screening infants and children at

the highest risk of having elevated blood lead levels. Indeed, during

its final year of operation, the program supported 54 community-

based projects through which some 535,000 children were screened.

Of these, 22,000 were found to have lead toxicity.

Despite this work, the program was terminated in 1981 and was

incorporated into the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Block

Grant (Title V of the Social Security Act), along with a number of

other public health programs (P.L. 97-35). Although information

about the use of the MCH Block Grant funds is difficult to obtain,

there have been a number of reports that lead screening activities

have been greatly reduced in several States since the repeal of the

Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act and the creation of the

MCH Block Grant. For example, a 1984 General Accounting Office

(GAO) study on the MCH Block Grant (GAO/HRD-84-35) found

that lead screening projects had received “the greatest reduction in

emphasis.” And a 1987 survey by the National Center for Educa-

tion in Maternal and Child Health indicated that 10 States had no

lead poisoning prevention activities at all.

With the publication of the Public Health Service’s report, “The

Nature and Extent of Lead Poisoning in Children in the United

States: A Report to Congress,” it is now clear that America’s lead

poisoning problem is still quite significant. Up to one million chil-

dren—one out of every 15—below 2p six have high blood lead

levels. Most of them will go undetected and untreated, however, be-

cause of structural and financial constraints that have been placed

on various public health programs. Without a targeted Federal

effort designed specifically to address this devastating and expen-

sive public health problem, there can be little expectation of

making important—and long overdue—progress in the near future.

HEARINGS

The Committee’s Subcommittee on Health and the Environment

held 1 day of oversight hearings on the proposed changes to the

Safe Drinking Water Act on December 10, 1987, and 1 day of legis-

lative hearings on H.R. 4939 on July 13, 1988. Testimony was re-

ceived from 19 witnesses, representing 17 organizations, with addi-

tional material submitted by 8 individuals and 5 organizations.

The Health Subcommittee also held 1 day of hearings on the

problem of lead poisoning in children and on the importance and

effectiveness of lead poisoning prevention programs on December 2,

1982 (Ser. No. 97-184). Testimony was received from 9 witnesses,

including a representative from the Department of Health and’

Human Services.

CoMMITTEE CONSIDERATION

On August 3, 1988, the Subcommittee on Health and Environ-

ment met in open session and ordered reported the bill H.R. 4939,

as amended, by voice vote. On September 29, 1988, the Committee

met in open session and ordered reported the bill H.R. 4939 with

amendment by voice vote.

3799

-

voi

e

n

s

"

t

o

m

$

a

E

E

r

t

2

R

r

A

A

EN

N

Pa

R

R

PL

E

R

a

AI

a

a

M

U

R

U

E

E

E

a

n

- e

n

T

m

~

W

M

E

R

E

SY

Ay

-*

H

E

>

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

[page 12]

ComMITTEE OVERSIGHT FINDINGS

Pursuant to clause 20X3XA) of rule XI of the Rules of the House

of Representatives, the Subcommittee held oversight hearings and

made findings that are reflected in the legislative report.

CoMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS

Pursuant to clause 20X3XD) of rule XI of the Rules of the House

of Representatives, no oversight findings have been submitted to

the Committee by the Committee on Government Operations.

CoMMITTEE COST ESTIMATE

In compliance with clause (a) of rule XIII of the Rules of the

House of Representatives, the Committee believes that the cost in-

curred in carrying out H.R. 4939 would be not more than

50,000,000 for fiscal year 1989, $52,000,000 for fiscal year 1990, and

$54,000,000 for fiscal year 1991.

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE ESTIMATE

U.S. CONGRESS,

CoNGRESSIONAL BupGEeT OFFICE,

Washington, DC, October 8, 1988.

Hon. JouN D. DINGELL,

Chairman, Committee on Energy and Commerce,

U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, DC.

Dear Mg. CHAIRMAN: The Congressional Budget Office has pre-

pared the attached cost estimate for H.R. 4939, the Lead Contami-

nation Control Act of 1988.

If you wish further details on this estimate, we will be pleased to

provide them.

Sincerely,

Yamal BiH

Acting Director.

1. Bill number: H.R. 4939.

2 Bill title: Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988.

3 Bill status: As ordered reported by the House Committee on

Energy and Commerce, September 29, 1988.

H.R. 4939 would authorize the appropriation of

grants to initiate and expend state programs for lead poisoning

screening, treatment and education.

This bill would direct the Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) to identify and publish a list of the brands and models of

drinking water coolers that are not lead free, including those which

have lead-lined tanks. Further, the bill would prohibit the sale of

those water coolers, and would direct the Consumer Product Safety

Commission (CPSC) to order within one year, manufacturers or im-

rters to repair, replace, or recall and provide a refund for coolers

po

with lead-lined tanks.

5. Estimated cost to the Federal Government:

3800

i

:

¥

¥

i

H

Authorization level...

Estmated outlays...

In addit:

velop a lis

agency ab

required r

the CPSC

year 1989.

The cost

Basis of E:

For the

would be e

priated ea:

authorized

that year.

patterns fc

6. Estim:

require ste

and remec

authorize

for grants

the amour

tration to

costs for t}

and $6 mil

_ Dependii

is found i

exceed the

extent of ¢

es of the House

at hearings and

sport.

es of the House

'n submitted to

perations.

ae Rules of the

hat the cost in-

ot more than

| year 1990, and

CE,

:tober 8, 1988.

Office has pre-

Lead Contami-

11 be pleased to

L. BLum,

ting Director.

88.

+ Committee on

ppropriation of

1ssist schools in

Irinking water.

hree years for

lead poisoning

tection Agency

and models of

‘ng those which

ibit the sale of

Product Safety

‘acturers or im-

‘und for coolers

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572

[page 13]

[By fiscal year, in millon of dollars]

—————

1989 19%0 1991 1952

Authorization level S0 52 54

——

In addition, CBO estimates that the requirement for EPA to de-

velop a list of water collers that are not lead free would cost the

agency about $0.5 million over 3 years. In order to carry out the

required recall of coolers with lead-lined tanks, we estimate that

the CPSC would have to spend about $0.2 million, mostly in fiscal

year 1989. ; :

The costs of this bill fall within budget function 300.

Basis of Estimate

For the purpose of this estimate, CBO assumes that H.R. 4939

would be enacted and that the authorized amounts would be appro-

priated early in fiscal year 1989. We also assume that the amounts

authorized in the bill for each fiscal year would be appropriated in

that year. The outlay estimates are based on historical spending

patterns for similar programs.

6. Estimated cost to State and local government: H.R. 4939 would

require states to establish programs to assist schools in testing for

and remedying lead contamination in drinking water, and would

authorize $30 million annually for fiscal years 1989 through 1991

for grants to states to pay for these programs. The bill would limit

the amount of the grant that could be used for program adminis-

tration to five percent. We estimate that total state administrative

costs for this program would be about $2 million in fiscal year 1989

and $6 million in fiscal years 1990 and 1991.

Depending upon the number of schools where lead contamination

is found in the water, the total cost of remedial actions could

exceed the amounts provided in the bill. CBO cannot predict the

extent of contamination, however, or the type of action that would

be taken to remedy the situation in each case. Because some

schools are already taking steps to remove contamination in drink-

ing water, not all the future costs associated with removing lead

from the drinking water in schools could be attributed to this bill.

The bill would also authorize the appropriation of $20 million in

fiscal year 1989, $22 million in fiscal year 1990, and $24 million in

fiscal year 1991 for grants to states to develop community pro-

grams designed to prevent lead poisoning.

7. Estimate comparison: None.

8. Previous CBO estimate: None. :

9. Estimate prepared by: Marjorie Miller.

10. Estimate approved by: C.G. Nuckols (for James L. Blum, As-

sistant Director for Budget Analysis).

INFLATIONARY IMPACT STATEMENT

Pursuant to clause 2(1X4) of rule XI of the Rules of the House of

Representatives, the Committee makes the following statement

3801

-

rl

=

=

F

I

L

S

—

—

—

A

E

E

g

e

s

A

s

-

S

R

I

-

p

e

;

L

A

ge

ai

a

a

I

E

A

.

od

.

er

at

ar

WA

FE

R:

ET

eA

a

it

n

i

S

T

E

t

n

i

e

s

gi

d

a

r

s

aw

a

R

d

4

a

a

y

Aah

f

r

S

r

u

d

s

i

n

n

iy

4

h

E

E

C

E

E

TE

ATR

HA

T

L

m

S

A

Po

d

-

T

R

I

E

A

A

T

ea

e

3

F

A

T

E

r

y

M

E

WE

RE

T

o

=

=

2

dp

S

e

n

(

n

i

h

RG

A

Ap

H

H

:

A

D

I

T

IE

R

ph

A

1

LE

Fa

T

E

T

N

A

A

R

S

n

He

Pr

in

BO

E

v

i

i

}

bei

¥

4

E

x

h

,

ae

d

i

R

R

A

E

T

I

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

[page 14]

with regard to the inflationary impact of the reported bill: The bill

will have no impact on inflation.

SECTION-BY-SECTION ANALYSIS

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT OF 1988

Section 1 :

Section 1 provides that this Act may be cited as the Lead Con-

tamination Control Act of 1988. :

Section 2

Section 2 includes provisions addressing contamination problems

from lead-containing water cooler, as well as provisions to address

lead contamination in school drinking water.

Section 2 includes the following amendments to the Public

Health Service Act.

Section 1461

Section 1461 includes definitions for terms used in this part. Sec-

tion 1461(2) defines “lead free” with respect to a drinking water

cooler. This term is defined with regard to the acceptable lead con-

tent of substances in contact with the drinking water. Water cool-

ers are not to be considered “lead free” where, in the course of

usual usage, corrosion is likely to place lead in contact with drink-

ing water, even if there is no direct contact at the time or manufac-

ture. The Administrator is authorized to establish more stringent

requirements for the acceptable lead content. The Committee ex-

pects the Adminstrator to examine carefully the issue of whether

water coolers with brass parts in contact with the water contribute

lead contamination in amounts comparable to other coolers not

considered lead free, in which case they should also be considered

not lead free.

Section 1462

Section 1462 directs the Consumer Product Safety Commssion to

issue an order requiring manufacturers or importers of water cool-

ers with a lead or a lead-lined water reservoir tanks to repair, re-

Place, or recall and provide a refund for, such coolers. This order is

to require that the repair, replacement, or recall and refund action

be completed within one year after enactment.

The Committee expects that the order will be issued promptly

following notice and opportunity for public comment, including a

public hearing, in order to provide sufficient time for the repair,

replacement, or recall and refund, action to be completed within

one year.

Section 1462 reflects a determiantion that water coolers with

lead-lined tanks present an imminent hazard that should be rapid-

ly addressed. EPA reports that eight of twelve tested coolers manu-

factured by Halsey Taylor have lead-solder lined tanks, and that

such coolers are associated with lead contamination levels of 2000

micrograms per liter. This contamination level is 400 times greater

than the 5 microgram per liter standard which the Agency has pro-

posed for lead contamination.

3802

In the oom

signle matter

og have I

by the US. E

the CPSC no

repair, replac

mined that a ©

Section 1468

This section

ers which are

This list is to

ing lead in cc

include on thi

fined in sectic

the course of

tact with drir

time of manu

ministrator tc

with brass pa:

nation in amc

free, in which

The Admin

brand and mc

these coolers

mittee, their

igh priority.

Section 146

of any water «

1988 subcomr

all reported t

not lead free.

such coolers «

1463(b) is int

longer be sol

they distribut

tions 1463(c) ¢

Section 1464

The Comm:

of lead conta

Impacts of ex

opment of ct

Public Healt

vides a thorot

tamination i;

dren each ye:

The recent

soning warns

Ee ————

* US. Public He.

and Extert of Leag

'° United States

Benefit Analysis,”

ted bill: The bill

{988

s the Lead Con-

nation problems

isions to address

+ to the Public

in this part. Sec-

drinking water

aptable lead con-

ater. Water cool-

in the course of

itact with drink-

ime or manufac-

1 more stringent

¢ Committee ex-

issue of whether

water contribute

ther coolers not

so be considered

ty Commssion to

ars of water cool-

aks to repair, re-

ers. This order is

ind refund action

issued promptly

ent, including a

e for the repair,

sompleted within

iter coolers with

. should be rapid-

ed coolers manu-

tanks, and that

ion levels of 2000

400 times greater

> Agency has pro-

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572

(page 15)

In the comment and public hearing stage of the CPSC action, the pl

signle matter at issue concerns whether the coolers in question do

in fact have lead-lined water tanks, and therefore should be listed

by the U.S. EPA under Section 1463. The Committee has.allowed

the CPSC no discretion to take any action other than ordering

repair, replacement, or recall and refund, once it has been deter-

mined that a water cooler has a lead or lead-lined tank.

Section 1468 “

This section directs EPA to publish a list of drinking water cool-

ers which are not lead free within 100 days following enactment.

This list is to specify the brand and model of water cooler contain-

in contact with drinking water. The Administrator is to

include on this list all water coolers which are not lead free as de-

fined in section 1461(2). Water coolers are to be included where, in

the course of usual usage, corrosion is likely to place lead in con-

tact with drinking water, even if there is no direct contact at the

time of manufacture. In addition, the Committee expects the Ad-

ministrator to examine carefully the issue of whether water coolers

with brass parts in contact with the water contribute lead contami-

nation in amounts comparable to other coolers not considered lead

free, in which case they should also be listed as not lead free.

The Administrator is also directed to separately identify each

brand and model of water cooler with a lead or lead-lined tank.

these coolers are considered imminent health hazards by the Com-

mittee, their prompt identification is expected to be treated as a

high priority.

Section 1463(b) includes a prohibition on the manufacture or sale

of any water cooler which is not lead free. In response to a January

1988 subcommittee inquiry, surveyed water coolers manufacturers

all reported that they had halted the sale of any coolers that are

not lead free. (One company, Halsey Taylor, had halted the sale of

such coolers only the previous month.) The prohibition in Section

1463(b) is intended to provide legal certainty that coolers will no

longer be sold which might elevate the level of lead in the water

they distribute. Civil and criminal penalties are established in Sec-

tions 1463(c) and 1463(d) for violation of this prohibition. ;

Section 1464

The Committee is extremely concerned about the health impacts

of lead contamination in school drinking water. The very serious

impacts of exposure to lead on the intellectual and physical devel-

opment of children is well documented. A recently released U.S.

Public Health Service Report on Childhood Lead Poisoning pro-

vides a thorough review.® EPA estimates that exposure to lead con-

tamination in drinking water is keeping more than 240,000 chil-

dren each year from realizing their full intellectua! capacity.'®

The recent Public Health Service Report on Childhood Lead Poi-

soning warns that water usage patterns in schocls—where water

» US. Public Health Service. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, “The Nature

and Extert of Lead Puisoning in Children in the United States: A Report to Congress, July 1988.

10 United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Keducing pond in Drinking Water. A

Benefit Analysis,” (1986), p. 24.

3803

ca

m

T

e

r

E

s

a

i

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

HOUSE REPORT NO. 100-1041

[page 16]

often sits untouched in pipes and water coolers nights, weekends,

and over summer and Christmas vacation—are especially condu-

cive to the accumulation of high lead contamination levels. Surveys

in a number of States, including California, Maryland, Minnesota,

New Jersey, North Carolina, and New Hampshire, have found high

lead levels at tested schools.

Under the program established in section 1464, public and pri-

vate schools in every state are to move as rapidly as possible to test

the lead contamination levels in their water, and take remedial

action as necessary to lower lead levels.

EPA is directed to distribute to the States within 100 days of en-

actment a list of drinking water coolers which are not lead free, as

well as a guidance document and testing protocol. The Committee

intends that the guidance document and testing protocol, as well as

the list of coolers, should assist schools and the general public in

evaluating the level of lead contamination from coolers and tap

water, and in taking remedial action to lower lead levels. States

are directed to distribute this material to local education agencies,

private schools, and day care centers.

States are given nine months after enactment to establish a pro-

gram to assist local education agencies in testing for and remedy-

ing lead contamination problems. These programs are to encom-

pass efforts to eliminate all sources to lead contamination in school

drinking water, including lead solder and lead pipes in school

plumbing, lead service lines, and lead containing water coolers. The

Committee also ex such programs to include efforts to secure

the water supplier's cooperation in lowering the corrosivity of the

drinking water, and therefore its tendency to leach lead. With spe-

cific regard to water coolers that are not lead free, the state pro-

grams are to assure that, within 15 months of enactment, all such

coolers within the jurisdiction of local education agencies are re-

paired, replaced, permanently removed, or rendered inoperable,

unless and found not to coma lead to drinking water.

At least one company, the Water Test Corporation of Manches-

ter, New Hampshire has offered to conduct free lead in drinking

water testing for public and private schools and day care centers

across the nation.

Section 1465

Section 1465 directs the Administrator to establish a grant pro-

fom to assist States in carrying out the school programs under

tion 1464. Grants under this program are to be available to help

defray the costs of testing for lead contamination, and remedial

action including efforts to remove lead pipes or solder, or to repair,

replace, permanently remove, or render inoperable water coolers

that are not lead free. No more than five percent of the grant

funds are to be used for program administration. Funds authorized

for this grant program are $30,000,000 for fiscal year 1989,

$30,000,000 for fiscal year 1990, and $30,000,000 for fiscal year 1991.

Section §

Section 3 establishes a program of technical and grant assistance

for the initiation and expansion of projects to detect and prevent

lezd poisoning in infants and children, regardless of its source.

3804

I

V

R

Grants are to

which must aj

and Human Se

retary is to g1

intend to serve

blood levels in

legislation aut

1990; and $24 r

As the legis]

to provide a m

ices to identify

(2) referral ser

of, and the er

with such bloo

ices to inform

ment, and pre

believes that €

an effective le:

plicants provic

for providing €

other, addition

application as

Among the 1

those for the °

and environme

medical treatr

sources, the le

priated under

Nonetheless.

children for le

tive are not gi

ronmental int

expected to pr

ate treatment

available and :

Once fundec

and children -

various medic

the State Mec

mandates tha

these two prog

can have easy

families with

or environme

have the oppo

of lead and, +

their children’

The Commi

grant funds b

poisoning prev

to continue ¢

being support.

should come -

Child Health

ts, weekends,

«cially condu-

ve found high

iblic and pri-

ossible to test

ake remedial

)0 days of en-

t lead free, as

1e Committee

sol, as well as

ral public in

Jlers and tap

levels. States

tion agencies,

tablish a pro-

and remedy-

re to encom-

tion in school

es in school

r coolers. The

rts to secure

osivity of the

ad. With spe-

‘he state pro-

sent, all such

;ncies are re-

d inoperable,

iter.

1 of Manches-

1 in drinking

' care centers

. a grant pro-

grams under

alable to help

and remedial

, or to repair,

water coolers

of the grant

ds authorized

| year 1989,

cal year 1991.

int assistance

. and prevent

of its source.

LEAD CONTAMINATION CONTROL ACT

P.L. 100-572

[page 17]

Grants are to be made available to State and local governments

which must apply to the Secre of the Department of Health

and Human Services for approval. In making such grants, the Sec-

retary is to give priority to those applications for programs that

intend to serve geographic areas with a high incidence of elevated

blood levels in infants and children. To carry out this purpose, the

legislation authorizes $20 million in FY 1989; $22 million in FY

1990; and $24 million in FY 1991. ’

As the legislation makes clear, grant projects must be designed

to provide a minimum of three types of services: (1) screening serv-

ices to identify infants and children with elevated blood Icad levels;

(2) referral services to provide access to program for the treatment

of, and the environmental intervention for infants and children

with such blood levels; and (3) outreach and public education serv-

ices to inform families and communities about the dangers, treat-