Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1980. 5291d8fa-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74e55520-4b19-4da2-987f-de37eb7fdcc2/carson-v-american-brands-inc-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

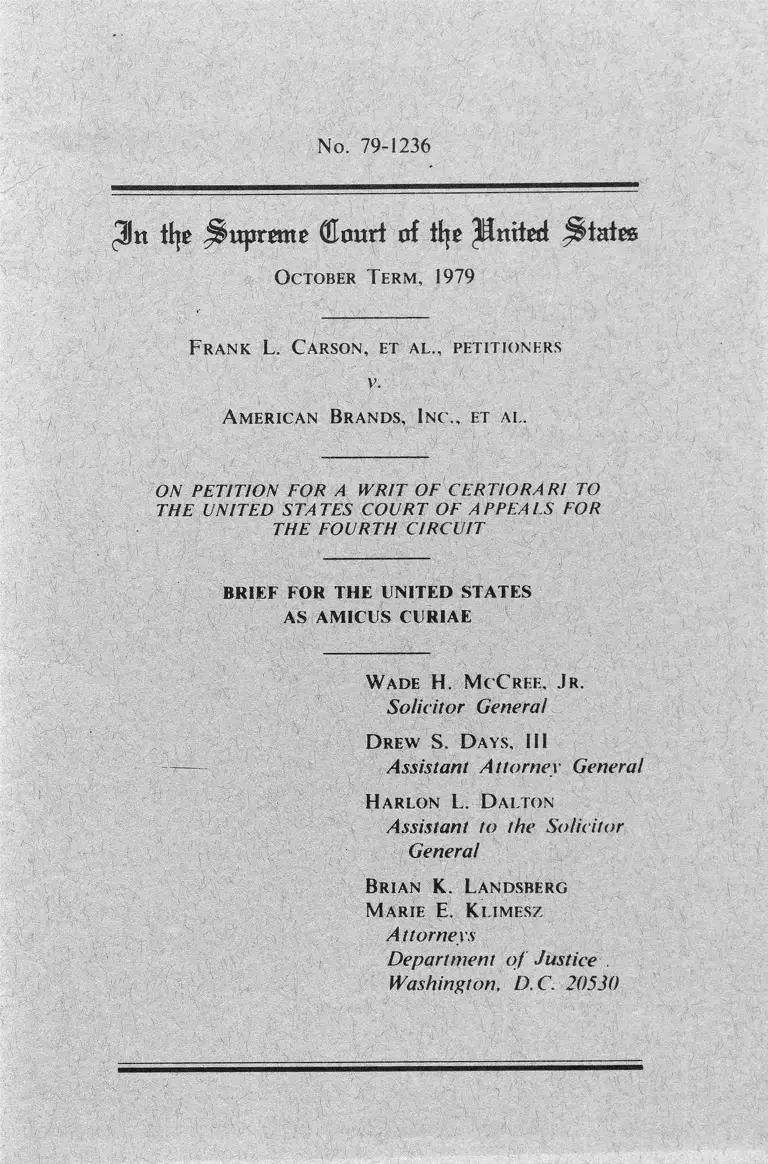

No. 79-1236

3n ttje Supreme Court of ttjt gutted States

October T erm, 1979

Frank L. Carson, et al., petitioners

v.

A merican Brands, Inc ., et al.

ON PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

W ade H. McC ree, J r.

Solicitor General

D rew S. D ays, III

Assistant Attorney General

Harlon L. D alton

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

Brian K. Landsberg

Marie E. Klimesz

A ttom e vs

Department of Justice ,

Washington, D.C. 20530

INDEX

Questions presented

Statement ..............

Discussion .............

Conclusion ...........

Page

2

5

1 I

CITATIONS

Cases:

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 ............................ ............. ................ 6

Baltimore Contractors, Inc. v. Bodinger,

348 U.S. 176 ............................... .................... . 7

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Cor/).,

337 U.S. 541 ..... .......... ........ ....... ........ ......... 7, 9

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesav,

437 U.S. 463 ................................................... 6, 9

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co.,

437 U.S. 478 ................................................... 5, 7

Massachusetts Mutual Life Co. v. Ludwig,

426 U.S. 479 ............. !.......................................... 2

NLRB v. Sears, Roebuck & Co.,

421 U.S. 132 ........................................................ 2

Norman v. McKee, 431 F. 2d 769 ................ 6, 10

Switzerland Cheese Ass’n v. E. Horne’s

Market, Inc., 385 U.S. 23 ............................ 5, 7

United States v. City o f Alexandria,

614 F. 2d 1358 ..................................................... 5

l

Page

Statutes and rule: .

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, Pub. L.

No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 253, 42 U.S.C.

2000e et seq.............................................. 2, 4, 6, 9

28 U.S.C. 1291 ....................... 1, 4, 6, 9

28 U.S.C. 1292 ........................................................ 7

28 U.S.C. 1292(a)(1) ............................ 1, 4, 5, 7, 9

42 U.S.C. 1981 .... .................... .............................. 2

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(e) ............................................. 2

ii

3n % Sitpmne Court of the United States

O ctober T erm , 1979

No. 79-1236

F rank L. C arson , et a l ., petition ers

v.

A m erican Brands , In c ., et al.

ON PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED S T A TES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

This brief is filed in response to the Court’s invitation

of April 14, 1980.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district court’s order refusing to

approve a consent decree providing for injunctive relief in

a Title VII case was appealable under 28 U.S.C.

1292(a)(1) as an order refusing an injunction.

2. Whether the district court’s order refusing to

approve a consent decree was an appealable final decision

under 28 U.S.C. 1291.'

'The remaining questions presented by the petition (Pet. 6-7), while

raised below, were not passed upon by the court of appeals since the

court determined that it lacked jurisdiction over the appeal. Under

(1)

2

STATEMENT

1. Petitioners, representing a class of black present and

former seasonal employees and applicants for employ

ment at the Richmond Leaf Department of the American

Tobacco Company, a subsidiary of respondent American

Brands, Inc., brought this suit on October 24, 1975 under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L.

No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 253, 42 U.S.C. 2000e el seq. and

under 42 U.S.C. 1981, alleging that the company and

respondent union had discriminated against black

workers in hiring, promotion, and transfer opportunities.

After conducting extensive discovery, the parties

reached an agreement settling petitioners’ claims, and

jointly moved the district court for approval of the

settlement pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(e) and entry of

a proposed consent decree. The district court, in a

memorandum opinion and order filed June 2, 1977,

refused to enter the proposed decree on the ground that it

illegally granted racial preferences to black employees

(Pet. App. 28a-51a).

On September 14, 1979, the court of appeals, sitting en

banc, dismissed petitioners’ appeal for lack of jurisdiction,

with Chief Judge Haynsworth and Circuit Judges Winter

and Butzner dissenting (Pet. App. la-27a).

2. The facts accepted as true by the district court for

the purpose of considering the consent decree

demonstrated that American Brands, Inc. has two

categories of employees—regular employees who work

year-round and seasonal employees who work an average

of six months a year (Pet. App. 29a-30a). Prior to

September 1963, certain of the regular job classifications

such circumstances, this Court ordinarily declines to consider issues.

See NLRB v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 421 U.S. 132, 163-164 (1975);

Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co. v. Ludwig, 426 IJ.S. 479

(1976).

3

were reserved for whites and all seasonal employees were

black (Pet. App. 30a). Although blacks were hired after

September 1963 into regular job classifications and, as of

February 1976, constituted 66% of the regular employees,

seasonal employees continue to be all black (ibid.).

Separate seniority rosters are maintained for regular

and seasonal employees. Seasonal employees may transfer

to regular positions only when no regular employee is

interested in the particular position, and in so doing they

lose all accumulated seniority (Pet. App. 30a). Since

seniority governs promotions, demotions, layoffs, recalls

and vacations, the loss incurred by transfer to a regular

position is significant (Pet. App. 31a).

Although blacks constitute 66% of the company’s

regular employees and 84% of its production unit, only

20% of the supervisory positions are held by blacks (Pet.

App. 31a).

The consent decree negotiated by the parties proposed

modifications of the seniority and transfer policies which

would allow seasonal workers to maintain their seniority

upon transfer to regular positions and would require that,

prior to hiring from the outside, seasonal employees be

given the opportunity to fill vacancies not filled by regular

employees for all hourly paid permanent production jobs

and for the job of watchman, formerly reserved for

whites (Pet. App. 32a-33a).2 The decree also eliminated

the requirement that seasonal employees serve an

additional probationary period after transfer to regular

positions (Pet. App. 33a). In addition, the decree set a

2Of 16 watchmen employed by the company in February 1976, only

one was black (Pet. App. 30a).

4

goal for the filling of production supervisory positions

with qualified blacks so that 1/3 of such positions would

be held by blacks by December 31, 1980 (Pet. App. 33a).

Finally, the proposed decree contained an injunction

prohibiting respondents from discriminating against black

workers and a three-year reporting requirement so that

compliance with its provisions could be monitored (Pet.

14).

3. The district court concluded that because

respondents expressly denied having discriminated against

the class of petitioners, the foregoing provisions of the

decree (which benefitted only seasonal employees all of

whom are black) constitute preferential treatment

prohibited by Title Vll and the Constitution (Pet. App.

32a, 45a-48a). The court also concluded that even if there

was evidence of present discrimination or the present

effects of past discrimination, the relief envisioned by the

decree would be inappropriate because it was not limited

to actual victims of that discrimination (Pet. App. 39a-

42a, 46a).

4. The court of appeals dismissed the appeal, holding

that the district court’s order refusing to approve and

enter the consent decree was neither a final decision

appealable under 28 U.S.C. 1291 nor an order refusing an

injunction under 28 U.S.C. 1292(a)(1) since “[t]he

immediate consequence of the order is continuation of the

litigation and * * * the merits of the decree can be

reviewed following final judgment” (Pet. App. 2a). The

court analogized the order to the denial of a motion for

summary judgment which, if granted, would include

injunctive relief, and to the denial of class certification

where the complaint seeks broad injunctive relief. Noting

that in both of those circumstances this Court has held

5

that no appeal would lie (Switzerland Cheese Ass’n v. E.

Horne’s Market, Ine., 385 U,S. 23 (1966); Gardner v.

Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., 437 U.S. 478 (1978)), the

court of appeals concluded that the result should be the

same here (Pet. App. 5a-6a).

Three of the seven judges dissented, concluding in an

opinion by Judge Winter that the order declining to

approve the consent decree was appealable under 28

U.S.C. 1292(a)(1) (Pet. App. 18a). The dissenting judges

distinguished the district court’s order from the refusal to

certify a class in Gardner, supra, reasoning that a refusal

to enter a consent decree cannot be effectively reviewed

following final judgment (Pet. App. 2Qa-21a). Similarly,

the dissenters distinguished the challenged order from the

denial of summary judgment in Switzerland Cheese,

supra, reasoning that here the district court conclusively

determined important issues adversely to petitioners’

claims (Pet. App. 21a).3

DISCUSSION

The decision below is in conflict with the Fifth Circuit’s

decision in United States v. City o f Alexandria, 614 F. 2d

1358 (1980), regarding whether a district court order

refusing to enter a consent decree containing injunctive

provisions is an order refusing an injunction within the

meaning of 28 U.S.C. 1292(a)(1).4 It is also in conflict

•Turning to the merits of the appeal, the dissenting judges

concluded that the district court abused its discretion in refusing to

approve the decree (Pet. App. 22a-26a). They would have modified

the decree, however, to give notice and an opportunity to object to a

sub-class for whom no relief was provided in the settlement.

T he court in City o f Alexandria sought to distinguish the instant

case as “relating to” a class action. 614 F. 2d at 1361 n.5. However,

“[t]he appealability of any order entered in a class action is

6

with the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Norman v. McKee,

431 F. 2d 769 (1970), regarding whether an order refusing

to enter a consent decree is a “final decision” within the

meaning of 28 U.S.C. 1291, Accordingly, review by this

Court is warranted.

Furthermore, the decision below frustrates an impor

tant congressional policy embodied in Title VI1 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. As this Court recognized in

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974)

(citations omitted):

Congress enacted Title VII * * * to assure equality

of employment opportunities by eliminating those

practices and devices that discriminate on the basis of

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

* * * Cooperation and voluntary compliance were

selected as the preferred means for achieving this

goal.

If appellate review of a district court’s refusal to enter a

consent decree is not available until after the case has

been tried and a final judgment entered, the benefits

envisioned by Congress from voluntary resolution of

employment discrimination claims will be irrevocably lost

to the parties. For this reason as well, further review is

warranted.

1. As a general rule, appellate review of district court

orders is limited by statute to final decisions. 28 U.S.C.

1291; Coopers & Lvbrandv. Livesav, 437 U.S. 463 (1978);

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra.

However, exceptions to the rule have been recognized

determined by the same standards that govern appealability in other

types of litigation.” Coopers & Lvbrandv. Livesav. 437 IJ.S. 463, 470

(1978).

7

both by judicial decision (see, e.g., Cohen v. Beneficial

Industrial Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541, 545-547 (1949)), and

by statute (28 U.S.C. 1292) where interlocutory review

would serve the interests of justice.

Section 1292(a) provides that “[t]he courts of appeals

shall have jurisdiction of appeals from: (1) [ijnterlocutory

orders * * * granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or

dissolving injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify

injunctions, except where a direct review may be had in

the Supreme Court.” An order refusing to approve a

consent decree providing for injunctive relief would

appear to come within that Section’s plain language.

However, this Court has stressed that Section 1292(a)(1)

“does not embrace orders that have no direct or

irreparable impact on the merits of the controversy.”

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra, 437

U.S. at 482. Thus, the touchstone for determining whether

an order falls within the Section is whether it is “of

serious, perhaps irreparable, consequence.” Baltimore

Contractors, Inc. v. Bodinger, 348 U.S. 176, 18! (1955).

In Switzerland Cheese Ass’n v. E. Horne's Market, Inc.,

supra, this Court held that an order denying a motion for

summary judgment was not “interlocutory” within the

meaning of Section 1292(a)(1) because it related only to

pretrial procedures and did not touch on the merits of the

claim. The Court noted (385 U.S. at 25) that the order

was “strictly a pretrial order that decides only one thing—

that the case should go to trial.” And in Gardner v.

Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra, this Court held

(437 U.S. at 480-481) that a denial of class certification

was not appealable under Section 1292(a)(1) because “[i]t

could be reviewed both prior to and after final judgment;

it did not affect the merits of [the plaintiffs] own claim;

and it did not pass on the legal sufficiency of any claims

8

for injunctive relief.” In contrast, the district court’s order

here did much more than merely advance the case to trial.

It determined that the relief agreed upon by the parties

could not legally be approved by the court. Since nothing

short of an admission of discrimination by the

respondents or a full trial on the merits (resulting in

findings of fact different from those to which the parties

stipulated for purposes of settlement) could have

persuaded the district court to grant the relief provided in

the consent decree, the parties were denied the opportuni

ty to settle their dispute voluntarily.

That opportunity, of course, cannot be recaptured once

the case goes to trial.5 Nor can the propriety of the court’s

refusal to enter the decree be reviewed after final

judgment. A settlement agreement reflects the parties’

assessment at a given point of the strengths and

weaknesses of their respective cases, and their assessment

of the advantages and disadvantages of, and risks and

uncertainties inherent in, going to trial. That state of

facts, of mind, and of perspective cannot faithfully be

reconstructed once intervening events have altered the

Notwithstanding the court of appeals’ observation (Pet. App. 8a)

that “[w]hen a district court objects to the terms of a decree,

alternative provisions can be presented, and perhaps a disapproved

decree may be entered with further development of the record,” as a

practical matter a refusal to enter a consent decree should be viewed

as a conclusive determination. Where alternative provisions prove

satisfactory to the parties, no appeal would be taken even if available.

On the other hand, where agreement cannot be reached, the

theoretical existence of alternatives should not foreclose appeal if the

court refuses to enter a decree for which agreement in fact has been

reached. Moreover, in the instant case there is no realistic possibility

of agreement on an alternative settlement since the district court’s

decision hinged not on any unfairness to either side in the agreed

upon settlement, but rather on the legal question whether the relief

sought in the proposed decree violates Title VII and the Constitution

in the absence of proven or admitted discrimination.

9

parties’ (and the court’s) view of the case. Moreover, to

the extent the facts adduced at trial vary materially from

the facts as they appeared at the time the consent decree

was rejected by the court, entry of a judgment based on

the terms of the decree is at least arguably improper.

Therefore, the district court’s order—given its un

reviewability at a later date, its roots in the premise that

the relief sought by the parties lacks a legal basis and is

itself unlawful, the fact that it deprives the parties of the

chance to settle their differences voluntarily, and the fact

that it prolongs rather than expedites resolution of this

case—comes within the purposes as well as the literal

terms of Section 1292(a)(1).

2. For the same reasons, the district court’s order is

appealable under 28 U.S.C. 1291 as a “collateral order.”

As this Court has said (Coopers & Lvbrand v. Livesav,

supra, 437 U.S. at 468), “[t]o come within the ‘small class’

of decisions excepted from the final-judgment rule by

Cohen [v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp. ], the order

must conclusively determine the disputed question,

resolve an important issue completely separate from the

merits of the action, and be effectively unreviewable on

appeal from a final judgment.” Viewed one way, the

district court’s order in this case touched significantly on

the merits in that the refusal to enter the consent decree

was based on the court’s opinion regarding what relief is

proper under Title Vll and what constitutes “preferential

treatment” under that statute. Viewed another way, the

order is wholly separate (or separable) from the merits.

Whether the consent decree should have been entered is a

question separate and apart from whether the plaintiffs

would prevail on the merits at trial were the facts

underlying the settlement agreement proved. Moreover, a

10

judgment on the merits would rest on facts actually

proved at trial rather than on the findings anticipated by

the parties for purposes of settlement. As the Ninth

Circuit observed in Norman v. McKee, supra, 43! F. 2d

at 773: “The proposed settlement is independent of the

merits of the case, it would not merge in final judgment.

Disapproval of the settlement is not a step toward final

disposition and it is not in any sense an ingredient of the

cause of action. In itself, the district judge’s order is final

on the question of whether the proposed settlement

should be given judicial approval.”6

Respondents argue (Br. in Opp. 6-10) that the questions presented

in the petition have been rendered moot by respondents’ withdrawal

of consent to the entry of the decree: We disagree. In submitting the

proposed decree to the court, the parties impliedly agreed to abide by

its terms if they are judicially approved. Had one of the parties

wished to repudiate the agreement before the district court had an

opportunity to act, it would not have been free to do so under the

terms of the agreement, though it would have remained free to argue

to the court that because of unforeseeable changed circumstances the

decree should not be entered (just as a party on like grounds can seek

modification of a decree). The same rule should apply on appeal.

Otherwise, a party’s right to take an appeal is conditioned on the

acquiescence of its adversary. Nothing in the proposed decree agreed

to by the parties to this case requires that result.

Parties should, of course, remain free to limit and condition their

assent to a settlement agreement as they see fit. Here the parties did

not enter into a separate agreement, but instead submitted a joint

proposed consent decree. Nevertheless, underlying every settlement

agreement, written or implied, is the implicit expectation that in

deciding whether to approve the settlement the district court will act

nonarbitrarily and in conformity with the law.

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

W ade H. M cC ree, J r .

Solicitor General

D rew S. D ays, HI

Assistant Attorney General

H arlon L. D alton

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

Br ia n K. Landsberg

M arie E. K lim esz

Attorneys

May 1980

D O J-1980-05

p [ i ■

* ̂ . . . s . / ■ \ - • ; '

ftkfft ; .]Ui,r. ftft\ i - ft.

;

.—;-feft, ftA.

ft? Xi

ft SM

f t

ftft KMMtt

.

vJfesafe i f i

:f tf t ■

;:- M M

> ■ ' •.■ f tf tf t ft* ft..: f t .ftft*ft. ':.v ' f t ' !

■ 8 M J

v: f t : ftft: . i ft ■ , !

Vv-r ftffctwS . *5 ■ : S H

' '

f t .' ' P '

.ft.ftO.ft gggpfc

.

f t v ft f ■ :

■ ' ft > ' . !

'

.< ■? - * -ft/y

, '-;X

' i - •... ,4s ;;W

iSSS

31

. ■

’

« f t

■ft ift

Ip?

ftil

k ft, ft. ft ,:k