Ruling on School Plans Submitted

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1970

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Ruling on School Plans Submitted, 1970. deaecd67-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/74eb3271-9402-42e2-ad85-810f980315e9/ruling-on-school-plans-submitted. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

ft ft # *

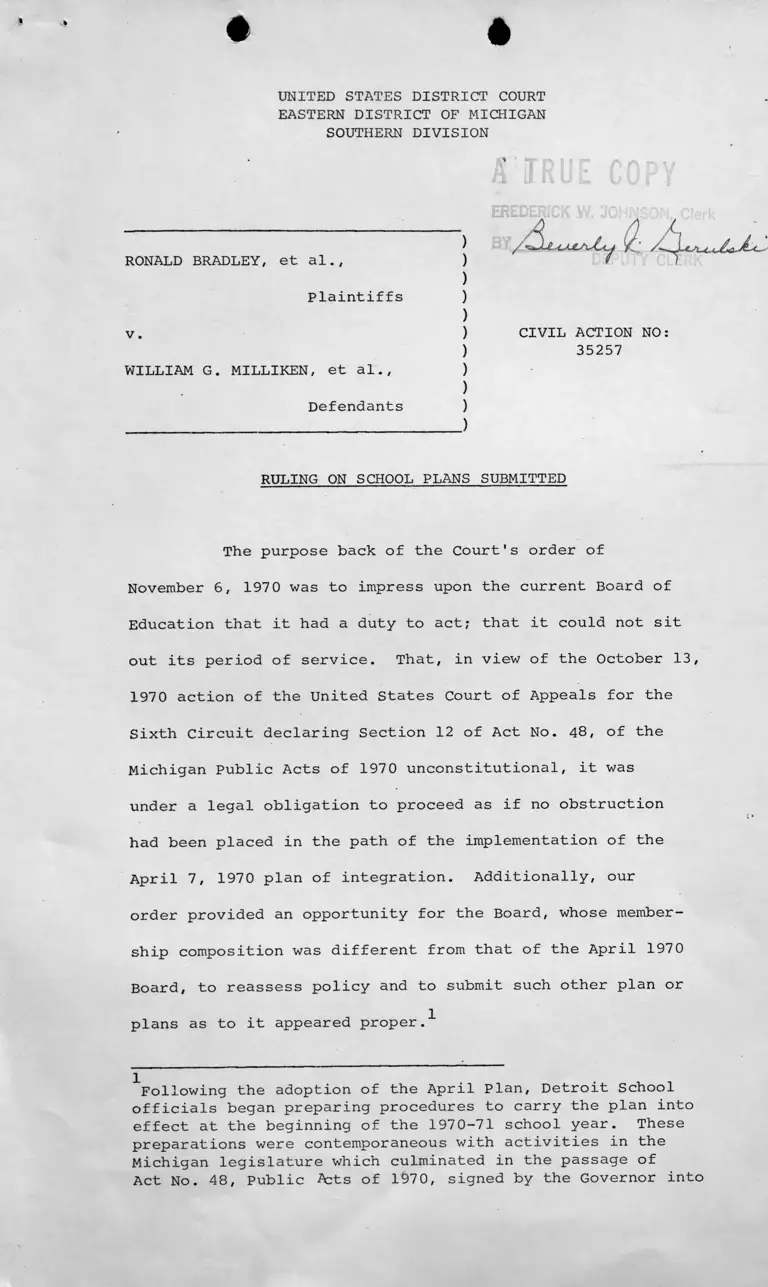

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)

RONALD BRADLEY, et al. , )

)

Plaintiffs )

)

v . )

)

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

)

Defendants )

___________ __________________________________________ )

CIVIL ACTION NO:

35257

RULING ON SCHOOL PLANS SUBMITTED

The purpose back of the Court's order of

November 6, 1970 was to impress upon the current Board of

Education that it had a duty to act; that it could not sit

out its period of service. That, in view of the October 13,

1970 action of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit declaring Section 12 of Act No. 48, of the

Michigan Public Acts of 1970 unconstitutional, it was

under a legal obligation to proceed as if no obstruction

had been placed in the path of the implementation of the

April 7, 1970 plan of integration. Additionally, our

order provided an opportunity for the Board, whose member

ship composition was different from that of the April 1970

Board, to reassess policy and to submit such other plan or

plans as to it appeared proper.1

Following the adoption of the April Plan, Detroit School

officials began preparing procedures to carry the plan into

effect at the beginning of the 1970-71 school year. These

preparations were contemporaneous with activities in the

Michigan legislature which culminated in the passage of

Act No. 48, Public A^ts of 1970, signed by the Governor into

The Board complied with the timetable set by

the Court and.submitted two plans differing from the April

plan, and indicated its "priorities" or preferences with

respect to the three plans. For the sake of brevity we

shall refer to the three plans as the McDonald, the

oCampbell and the April Plans.

Procedurally the Court has before it for

disposition the motion of plaintiffs to order immediate,

that is, February 1, 1971 (the beginning of the next

semester), implementation of the April Plan, and the

defendant Board's alternates in the form of the McDonald

and Campbell Plans.

We begin our consideration of the three plans

with some generalizations and basic concepts. Society is

but a group of beings organized to meet common needs.

Child-raising, that is, education, is the first and

largest industry of every species, including man. If a * 2

law on July 7, 1970. One of the effects of the Act was to

delay the implementation of the April Plan for at least a

year. Meanwhile, a recall movement was initiated against the

four members of the Board who had voted in favor of the

April Plan; a movement which, on August 4, 1970, resulted in

the removal of the said members of the Board. These four

seats on the Board were vacant at the time of the filing of

the complaint in this action, but were filled by appointment

by the Governor on August 31, 1970 (terms expiring December 31,

1970). The present Board will cease to exist at the end of

this year, and a thirteen-member Board will come into

existence on January 1, 1971. Only three of the present Board

members will continue on the new Board. The new Board will

be composed of five members at large and the eight chairmen

of the regional boards.

2It should be noted that neither Mr. McDonald nor Mrs. Campbell

claims sole credit for the formulation of these plans, but

they are their principal architects and spokesmen. Each of

these plans represents a composite of contributions from

other persons, including, in no small way, those of school

staff people.

- 2 -

• #

given society is to survive it must discharge its responsi

bility to its young. Fortunately for us, there is something

in the nature of man which drives him to develop his

peculiar endowments, and it is through learning that we

make the best or worst of those endowments. A school

system is but one, and perhaps the most important, way in

which the human society discharges its responsibility to

its young, to itself and to its survival. When we do this

well the educator calls it "quality education." In a

heterogenous society such as ours we are satisfied that

such an education cannot be attained without integration.

Our objective then, as the Court sees it, is not integration

in itself - which, if achieved in the wrong way, can be

counter-productive - but the best education possible,

with its sine qua non: integration. Integration for

integration's sake alone is self-defeating; it does not

advance the cause of integration, except in the short haul,

nor does it necessarily improve the quality of education.

To put it simply, a good education, to say nothing of the

best education, cannot be achieved without integration.

To place us in our particularized situation, we

have in Detroit a community (society) generally divided by

racial lines. To make it an effective society in discharging

its most important function it is necessary that the people

of the city recognize their true goal and take such steps as

will assure its attainment. A society best fulfills its

educational function when it presents its members, and

particularly its young, with equal opportunities to achieve

identity, experience stimulation, and attain a decent

measure of security. There is within each child an innate

- 3 -

force pressing upon him to fulfill whatever potentials he

possesses, and an educational system which recognizes

this and programs its efforts in this direction is the one

most likely to succeed in attaining its goal.

Keeping these basic truths in mind, we turn to

a consideration of the plans before the Court. We shall

not here recite in detail the features of the three plans

which, however, are before us as part of the record.

For the purposes of our present ruling we consider

the Campbell, or "Magnet Curriculum" Plan, albeit perhaps

an "exciting concept of secondary education," as one which

does not lend itself to early implementation because of the

programming and operational difficulties which attend it.

It is a distinctive departure from past and present

practices, and lacks a background of experience. The most

obvious question mark concerning it is its impact upon the

achievement of identity. It is best viewed as an

educational concept meriting study by our educators.

Laying aside the Campbell Plan, we turn to the

remaining plans: the April Plan and the McDonald or

"Magnet School" Plan. It is the plaintiffs' view, as we

understand it, that the Court is limited to considering

only the April Plan at this time. This view we do not share.

The defendant Board takes the position that, absent a

finding that the Detroit school system is a segregated one -

an issue necessarily relegated by us to the hearing on the

merits - the Court lacks authority to order any plan into

effect. It will become plain in the course of our ruling

that the Court does not believe this to be so.

- 4 -

The McDonald Plan is intended to achieve

integration by providing a specialized curriculum at

certain high schools. Each of such specializing schools

would serve two of the eight regions of the school system,

with the expectation of drawing students from a wider area,

thus bringing about a built-in and, hopefully, a greater

degree of integration. The categories of specialization

would be Vocational, Business, Arts and Science. The

plan is voluntary, and all high schools, including the

so-called magnet schools, would offer a regular high

school curriculum for students living in the present high

school attendance areas.

The April Plan would redraw the school feeder

patterns for 11 of the city's 21 high schools (not counting

Cass Technical High School) so as to improve integration in

the affected schools. It is designed to be progressive in

application, affecting some 3,000 students graduating from

junior high schools in each of three successive years.

Both the McDonald and April Plans have other

features which we do not here detail, but which we take into

account in our appraisals.

Comparing the McDonald and April Plans, it appears

to us that the April Plan's principal aim is to improve

integration by the "numbers,1 as several witnesses

described it. Whether in the long run it will do even that

is a serious question. It is a plan which does not take

into account the basics which we have heretofore mentioned,

and it does not offer incentive to or provide motivation

for the student himself. Instead of offering a change of

- 5 -

diet, it offers forced-feeding. The McDonald Plan on the

other hand, we believe, offers the student an opportunity

to advance in his search for identity, provides stimulation

through choice of direction, and tends to establish security.

That it will promote integration to the extent projected

remains to be seen, but based on the experience in this

same school system, i.e., Cass Technical High School, it

holds out the best promise of effective, long-term integration.

It appears to us the most likely of the three plans to

provide the children of the City of Detroit with quality

education as we have defined it. The McDonald Plan has

been characterized by the plaintiffs as an experiment. The

short answer to this is that all plans are experiments,

just as is life itself. To sum up, in our view the McDonald

Plan is the best of the plans before the Court.

We pass now to considering the role of the Court

so far as implementation is concerned. Whether we view

the present situation from Court—side or Board-side, it

appears to us that the Board is required to proceed with

the implementation of the plan. It has on its own shown a

preference for the McDonald Plan - we believe justifiably so.

The question remaining is when to put the plan into effect.

There have been expressions by some of the witnesses that any

of the three plans could be implemented by February 1, 1971.

It appears to us that the McDonald Plan, calling as it does

for rather radical and comprehensive changes, cannot be

properly implemented until September 1971 - the beginning

of the next school year. (We do not mean to imply that any

less time would be need for implementation of the other plans.)

- 6 -

#

If to integrate is "to combine to form a more

complete, harmonious or coordinated entity,"3 then the

plan we have chosen is, of the three, most likely to be

productive. It places the emphasis not on "desegration"

4(representing the legal rights of Blacks), but on

5"integration" (an ideal of social acceptability).

Added to the already serious problems of administer

ing the affairs of their offices, the members of the Detroit

Board of Education, past, present and future, the Superin

tendent, the administrative staff and the faculty, are

beset by a decentralization decree which cannot but involve

every aspect of school administration and school programming.

The ordered decentralization has been characterized by the

Superintendent as a novel one - one never before attempted

in any other school district in the United States regardless

of size. It introduces confusion over the proper roles of

the regional and central boards. That it will lead to

controversies between them appears evident; that it

aggravates, not lessens, the problems besetting the

administrators is plain; and that it may fan the fires of

discontent among the citizenry is likely. If a unified

school system for the City of Detroit is the aim, then

the combination of centralization and decentralization,

with their attendant questions of jurisdiction, control

and responsibility, appears to have missed the mark. At

3

Webster's Third New International Dictionary.

4A Dictionary of American Social Reform.

5

Ibid.

- 7 -

#

the least it will require time and call for much effort

on the part of all involved in their several official

stations/ working cooperatively, to stabilize the Detroit

school system into a smoothly working framework of

management

We turn next to the legal posture of the case.

Plaintiffs have cited Alexander v . Holmes County Board of

Education/ 369 U.S. 19/ 24 L.Ed.2d 19 (1969), and

Keyes v. School District No. One/ Denver/ Colorado/

313 F. Supp. 61 (D. Colo. 1970). We consider neither

to be in point so far as our present issue is concerned.

We cannot at this point proceed on the assumption that

plaintiffs will succeed in proving their claim/ in the

hearing on the merits, that the Detroit school is a

segregated school system, de jure or de facto.

While the question of whether the United States

Constitution, as interpreted by the Supreme Court of the

United States, not only prohibits discriminatory segregation

according to races, but also requires integration, has

7not yet been decided by that Court, we believe that

6

What further and additional problems will result from the

passage of the so-called Parochiaid Amendment to the Consti

tution of the State of Michigan, we cannot say. What is

obvious is that the proposed closing of some or all Catholic

parochial schools in the Detroit diocese will put further

strains on the school system of the city.

7

There are school cases now pending before the Supreme Court

in which it may well have an opportunity to answer that

question and respond to the call of Chief Justice Burger to

"clear up any confusion concerning the Court's prior mandates

in school desegregation cases, and to resolve some of the

basic practical problems * * * including whether, as a

constitutional matter, any particular racial balance must be

- 8 -

8

consistent with that Court's rulings, where a school

district has taken steps enhancing integration in its

schools it may not reverse direction. In the setting of

our case nonaction is (or amounts to) prohibited action.

This is also our reading of the opinion of our court of

appeals in ruling upon the appeal taken from our former

decisions in this case. The court said:

" * * * In the present case the Detroit Board

of Education in the exercise of its discretion

took affirmative steps on its own initiative

to effect an improved racial balance in twelve

senior high schools. This action was thwarted

or at least delayed, by an act of the State

legislature."

It also pointed out that "State action cannot be interposed

to delay, obstruct or nullify steps lawfully taken for the

purpose of protecting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment." It follows from this that any action or failure

to act by the Board of Education designed in effect to

"delay, obstruct or nullify" the previous (April 7th) step

toward improving racial balance in the Detroit schools is

prohibited State action.

It is our judgment that the McDonald Plan is superior

to the other two plans before the Court in advancing the

cause of integration, and that preparations should be

achieved in the schools, to what extent school districts and

zones may and must be altered as a constitutional matter, and

to what extent transportation may or must be provided to

achieve the ends sought by prior holdings of the court."

See Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. of Memphis, 397 U.S. 232,

25 L.Ed.2d 246 (March 9, 1970).

8

See cases cited in the opinion of the Sixth Circuit Court

of Appeals in the prior appeal in this cause, pages 10 and

11 of the slip sheet.

- 9 -

-» * * # #

started immediately for its institution at the beginning

of the next full school year in September 1971. The

administrative work involved in a transformation to the

McDonald Plan requires, and the staff deserves, lead time

in which to program and prepare for its establishment.

The course of action taken by the Court will

provide the present and incoming Boards a sense of

direction, give the administrative staff both direction

and time for an orderly transition, and allow students an

opportunity to anticipate the changes in educational

offerings so that they may exercise the choices which will

open to them. It is our belief that in this way the

students, in their quest for identity and in their inherited

drive for realizing their potentials, will bring about such

integration as no coercive method could possibly achieve.

The foregoing constitutes our findings of fact and

conclusions of law.

An appropriate order may be submitted.

DATED: December 3, 1970_____

at Detroit, Michigan.

- 1 0 -