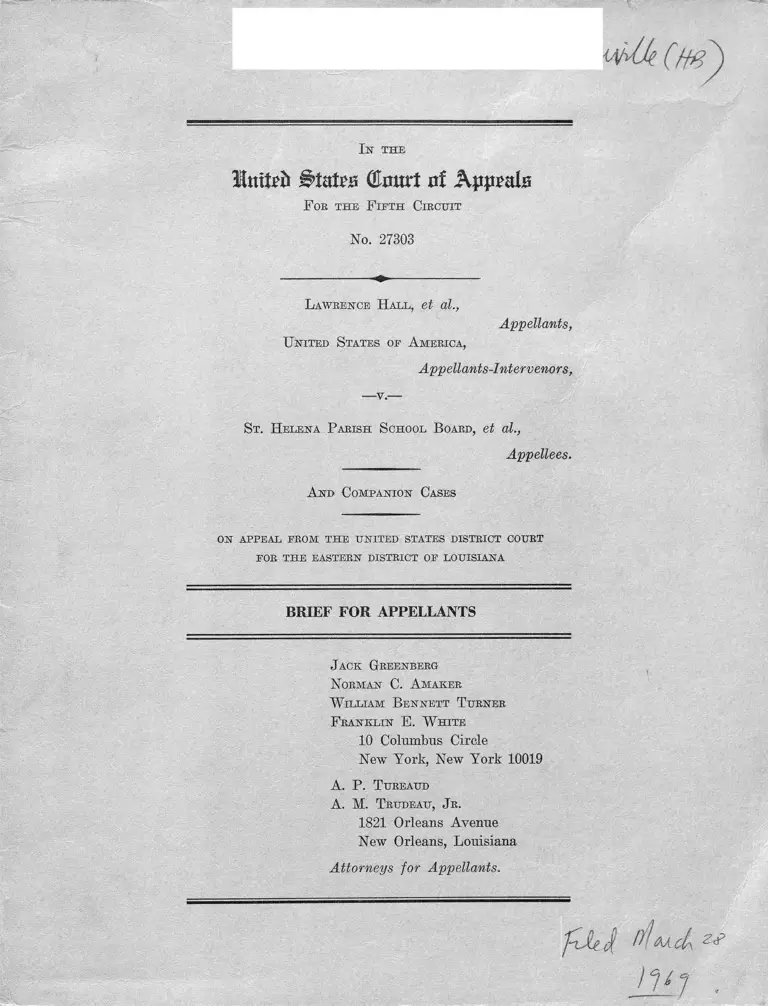

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 25, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1969. a23cc627-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7510d007-24dc-4a05-9c32-d9a88004606f/hall-v-st-helena-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

Initri* BtnttB (£m*rt at Kppmh

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 27303

L awrence H all, et al.,

Appellants,

United States of A merica,

Appellants-Intervenors,

— v .—

St. H elena P arish School B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

A nd Companion Cases

on appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

Norman C. Amaker

W illiam Bennett Turner

F ranklin E. W hite

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. Trudeau, J r.

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants.

INDEX

Table of Cases

Issue Presented

Statement

I . History of the Litigation

II. Proceedings Since Green

a. Initial Hearing -- loss of the

1968-69 school year.

b. The Evidence at the Final Hearing

III. The District Court's decision

Argument

I . Introduction

II. Appellees may no longer constitutionally assign

students pursuant to their choice

a . Jefferson

b . Green and Greenwood

c. Continuation of Racially Identifiable

Schools

d. Some observations on the District Court's

Opinion

III. This Court Must Prescribe Procedures Guarantee

ing The Implementation of Other Plans by the

Opening of the 1969-70 School Year.

Page

11

vi

1

1

2

3

4

6

7

7

12

12

13

16

20

23

IV. Conclusion 28

l

TABLE OF CASES

Cases Page

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181, 188 (5th

Cir. 1968) 4, 16

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 1,7,9,18

Carter v. Feliciana School Board, CA No.

3249 3

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 7 18

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Educa

tion, 273 F.Supp. 289, aff'd 394 F.2d 410

(4th Cir. 1968) 20

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th cir. 1960) 9

George v. Davis, President, East Feliciana

Parish School Board No. 3253 3

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of

Dade County, 272 F.2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) 9

Graves v. Walton County Board of Education,

403 F .2d 189 (5th Cir. 1968) 16

Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430, 441-2

(1968) 1,2,4,13,19

Hall v. West, 335 F.2d 481 (5th Cir. 1964) 24

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

District, No. 23255, March 6, 1969

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District, No. 22, 378 F.2d 483,

490 (8th Cir. 1967)

16

1919

Cases (cont.)

Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178, 183 (8th

Cir. 1968)

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, 276

F.Supp. 834, 838, 851 (E.D. La. 1967)

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

1965)

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F.2d 836, aff'd with modi

fications on rehearing en banc. 380 F.2d

385, cert, denied sub, nom. Caddo Parish

School Board v. United States, 389 U S

840 (1967)

Other Authorities

Campbell, Cunningham and McPhee, The

Organization and Control of American

Schools. 1965

Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment

of Pupils to Public Schools, 45 Va.L .Rev.

517 (1959)

M. Hayes Mizell, The South has Genuflected

and Held on to Tokenism, Southern Educa-

tion Report, Vol.3, No. 6 (Jan./Feb. 1968)

Southern School Desegregation. 1966-67, A

Report of the United States Commission on

Civil Rights, July, 1967

Survey of School Desegregation in the

Southern and Border States. 1965-1966,

United States Commission on civil Rights,

February, 1966

Page

11

8, 10

23

1,2,6,12,21

7,8

7

11

10

10

1 X 1

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 27303

LAWRENCE HALL, et al.,

Appellants,

UNITED STATES,

Appellant-Intervenors,

v .

ST. HELENA PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

JAMES WILLIAMS, JR., et al. ,

Appellants,

UNITED STATES,

Appellant-Intervenors,

v .

IBERVILLE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

IV

YVONNE MARIE BOYD, et al.,

Appellants,

UNITED STATES,

Appellant-Intervenors,

v.

THE POINTE COUPEE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

TERRY LYNN DUNN, et al.,

Appellants,

UNITED STATES,

v.

LIVINGSTON PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

DONALD JEROME THOMAS, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

WEST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

v

#

WELTON J. CHARLES, JR., et al. ,

Appellants,

UNITED STATES,

Appellant-Interveners,

v.

ASCENSION PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, and GORDON WEBB,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ISSUE PRESENTED

Whether the district court erred in approving the

continued use of free choice without requiring appellee

school boards to submit alternative plans eliminating

racially identifiable schools, where only a small fraction

of Negro students are enrolled in previously all-white

schools and where free choice has permitted the mainten

ance in each district, of several all-Negro schools.

v i

STATEMENT

Appellants in these six school desegregation cases seek the

elimination of the racially identifiable schools maintained by

each of these school districts in violation of their rights under

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (Brown I) 349 U.S.

(Brown II).

These cases bear many "service stripes." The instant appeals

are from orders denying motions for further relief seeking to

implement the decision of the United States Supreme Court in Green

v. County School Board of New Kent County, Va., 391 U.S. 430, by

securing the adoption of plans other than freedom of choice.

I. History of the Litigation

None of these school districts took any steps toward desegre-

i /gation until ordered to do so. During 1965, the district court,

the Honorable E . Gordon West, entered in each case desegregation

plans which provided for a right to transfer after an initial racial

assignment under the old dual zones.

After the decision of this Court in United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 U.S. 836 (5th Cir. 1966) affirmed

with modifications on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385, cert den. 389

U.S. 840, appellants and/or the United States, intervenor in all

The St. Helena case is well known in this Circuit having been

here on numerous occasions; it was commenced in 1952. The other

cases were filed in 1964 and 1965. Until then, and in complete

and total defiance of Brown, each district maintained separate

systems for Negro and white students.

V

f

but the West Baton Rouge case, filed motions for further relief

to conform the 1965 order to the model decree prescribed in

Jefferson. On May 19, 1967, Judge West entered in each case

identical "amending and supplemental orders" which purported to

change and/or make such additions to the earlier plans as was

necessary to bring them into conformity with the Jefferson decree.

However, the amended orders failed to conform to Jefferson in many

important respects not the least of which was that it left intact

the procedure for initial racial assignments with the right to

transfer out and failed to require the filing of reports.

Appellants sought and were granted, on August 4, 1967, summary

reversals of the May 19, 1967 orders. On August 7, 1967, the district

court entered in each case the free choice model decree prescribed

by Jefferson.

II. Proceedings Since Green

Following the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in Green, appellants and/or the United States filed, in June and

July 1968, motions for further relief alleging, in each case, that

the freedom of choice plans had failed to effect unitary systems,

that other methods of pupil assignment promised speedier conversions

and requesting that the Boards be directed to prepare and implement,

by the opening of the 1968-69 school year, plans incorporating

o the r me tho ds.

2

a. Initial Hearing -— loss of the 1968-69

school year

On July 19, Judge West conducted a joint hearing in some

2/eight cases, these six and two others. After argument of counsel,

but without evidentiary hearing, he denied so much of the motion

that sought relief for the 1968-69 school year. Although most of

the parishes only had between 10 and 15 schools, Judge West stated

that:

these questions simply cannot be

intelligently answered or a new

plan implemented or rejected before

the commencement of the school year

in September 1968. (July 19th

transcript p. 38).

He continued the cases for a further hearing on November 4, 1968.

Some of the questions he wanted time to review before ruling

on Green were:

1. Whether he had the power to modify the decree

of this Court in Jefferson.

2. Whether this was not, in fact, a new lawsuit.

3. Whether or not the relief requested would violate

the so-called "anti-busing" provisions of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

Believing that these questions were insubstantial and that it

was possible to develop plans for most, if not all of these districts,

2/ Carter v . West Feliciana parish School Board; C.A. No. 3248;

George v . Davis, President, East Feliciana parish School Board,

Civil Action No. 3253.

It was quite clear, even then, that zoning would eliminate

needless busing made necessary by free choice.2/

f

appellants sought summary reversal in this Court. On August 20th,

1968, the motion was denied, along with similar motions in some 40

other cases. Adams v. Mathews, 403 F .2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968).

However, the Court announced careful procedures to be observed by

district courts in this Circuit faced with Green motions. They

were directed (1) to hold hearings no later than November 4, 19 69;

(2) to decide whether the existing plan was adequate to effect the

conversion to a unitary system now; (3) that, in determining the

adequacy of the existing plan, the following rule applied: (403

F.2d at 188) .

If in a school district there are still

all-Negro schools, or only a small

fraction of Negroes enrolled in white

schools, or no substantial integration of

faculties and school activities then, as

a matter of law, the existing plan fails

to meet constitutional standards as

established in Green.

The cases were remanded for further proceedings.

b. The Evidence at the Final Hearing

Briefs were filed with the district court prior to November 4,

1968. At the hearing held that day, appellants rested on the

board's own reports. We contended that such reports showed on their

face that freedom of choice had failed to and was incapable of

disestablishing the dual system and that the court was bound under

Green and Adams to require the submission of alternate plans. The

United States went further; it submitted depositions of the various

superintendents, in which they were examined concerning, inter alia,

4

f

the feasibility of other methods of pupil assignment. Thus, the

Court had before it not merely the results of the free choice plans,

but also alternate proposals of pupil assignment.

The record then before the district court discloses the

following:

(1) Each of the school boards had utilized some kind of

free choice plan, whether permissive or mandatory for at least

four years (St. Helena and Iberville are in their fifth year);

(2) In none of these districts has a white child ever chosen

or actually attended a previously all-Negro school, so that each

district maintained its all-Negro schools as before;

(3) During the 1968-69 school year less than 10% of the

Negro students in each of these parishes actually attend formerly

all-white schools. In four of the six the percentage is less than

five. And, most importantly, the percentage declined in two:

Pointe Coupee and Livingston. In Pointe Coupee it went from 6.7%

in 1967-68 to 4.5% in 1968-69. In Livingston from .8% in 1967-68

to .4% (7 children) in 1968-69.

i/The following table reveals the extent of student desegregation

and the number of all-Negro schools for the 1968-69 school year.

Parish

% of Negro Students

In Previously all-

White Schools

All-Negro Years of Use

Schools of Free Choice 5/

St. Helena 3.6 7 5

Iberville 9.8 9 5

Pointe Coupee 4.5 5 4

Livingston .4 4 4

Ascension 4.0 5 4

West Baton Rouge 5.8 5 4

4/ Based on Fall 1968 reports to the Court.

5/ The re suits in each of the prior years is summarized in

great detail in the Appendix to the Government's brief.

5

Ill. The District Court's Decision

On January 7, 1969, Judge West filed his opinion and order

denying the motions for further relief in these six cases and

6/

in the two Feliciana cases (Note 2, supra.) He found that the

imposition of the Jefferson decree had resulted in an increase

from .8% to 5.0% in the number of Negroes attending white schools

"in the eight parishes”; he concluded that "considerable progress"

has been made and that "further progress, as hereinafter indicated

can be made under this plan."

While conceding that the dual system had not been disestablished,

he put the blame on the failure of the boards to implement fully all

provisions of the Jefferson decree. He found in particular, that

several of the Boards had not — as the Jefferson decree required --

assigned students failing to exercise a choice to the geographically

nearest school. Said the Court;

a strict adherence to these requirements

will resuit in the disestablishment of a

state imposed dual system of schools such

as is forbidden by existing law, while

at the same time preserving the freedom of

choice that this Court sincerely believes

to be a constitutionally guaranteed right

of every pupil. (Slip Op. 9.)

On the question what if the free choice decree were fully

carried out, completely unfettered — but it nonetheless continued

schools attended solely by white or Negro children, the Court

said;

6

such would be the result of free choice

or of de facto segregation, which, under

the present state of the law, does not,

in this Court's opinion, violate constitu

tional mandates. Certainly there is nothing

more democratic than freedom of choice. This

simply must be preserved, (ibid).

Notice of Appeal was filed January 23, 1969. a motion to

Expedite these cases and for leave to proceed on the original

record was filed February 7, 1969, and granted March 12, 1969.

ARGUMENT

I . Introduction

Fourteen years ago the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional

the maintenance of separate schools for white and Negro children.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Separate schools

for the races, however, are being maintained in all of the cases

be fore this court. For a decade after Brown the de fendant school

boards made no attempt to dismantle their dual racial school

systems. They have made but token efforts since the commencement

of these actions. The right to desegregated educational opportunities

established by Brown has never been realized by the overwhelming

majority of Negro children in these parishes. They will never be

enjoyed if the free choice plans now being used are permitted to

continue.

The most marked and widespread innovation in school administra

tion in southern and border states in the last fifty years has been

ythe change in pupil assignment method in the years since Brown,

from geographic attendance zones to so-called "free choice." Prior

6/ See generally, Campbell, Cunningham and McPhee, The

Organization and Control of American Schools, 1965. ("As

a consequence of [Brown v. Board of Education, supra],

the question of attendance areas has become one of the most

significant issues in American education of this Century" (at 136) .)

t° Brown, systems in the north and south, with rare exception,

1 /assigned pupils by zone lines around each school.

Under an attendance zone system, unless a transfer is granted

for some special reason, students living in the zone of the school

serving their grade would attend that school.

prior to the relatively recent controversy concerning segrega

tion in large urban systems, assignment by geographic attendance

zones was viewed as the soundest method of pupil assignment. This

was not without good reason; for placing children in the school

nearest their home would often eliminate the need for transportation,

encourage the use of schools as community centers and generally

8/

facilitate planning for expanding school populations.

7/ "In the days before the impact of the Brown decision began

to be felt, pupils were assigned to the school (corresponding,

of course to the color of the pupils ' skin) nearest their

homes; once the school zones and maps had been drawn up, nothing

remained but to inform the community of the structure of the

zone boundaries." Ventrees Moses v. Washington parish School

Board, 276 F . Supp. 834 (slip op. 15-16) (E.D. La. 1967).

See also Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment of Pupils

to Public School, 45 Va. L . Rev. 517 (1959), "until now the

matter has been handled rather routinely almost everywhere by

marking off geographical attendance areas for the various

buildings. In the South, however, coupled with this method

has been the factor of race."

8/ Campbell, Cunningham and McPhee, supra, Note 6 at p. 7.

By showing that zone assignment was the norm prior to Brown,

we intend merely to indicate the background against which

free choice was developed. We recognize that the use of zones

is not always the most desirable method of pupil assignment.

8

In states where separate systems were required by law, this

method was implemented by drawing around each white school

attendance zones for whites in the area, and around each Negro

school zones for Negroes. In many areas lines overlapped because

there was no residential segregation. Thus, in most southern

school districts, school assignment was largely a function of three

factors: race, proximity and convenience.

After Brown, southern school boards were faced with the problem

of "effectuating a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory system"

(Brown II at 301). The easiest method, administratively, was to

convert the dual attendance zones into single attendance zones,

without regard to race, so that assignment of all students would

Vdepend only on proximity and convenience. With rare exception,

however, southern school boards, when finally forced to begin

desegregation, rejected this relatively simple method in favor of

the complex and discriminatory procedures of pupil placement laws,

1 0 /and when those were invalidated, switched to what has m practice

9/ Indeed, it was to this method that this Court alluded in

“ Brown II when it stated " [t]o that end, the courts may consider

problems related to administration, arising from . . . revision

of school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a non-racial basis" (349 U.S. at 300-301).

10/ For cases invalidating or disapproving such laws, see

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302

F.2d 818 TSth Cir., 1962); Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction

of Dade County, 272 F.2d 763 (5th Cir., 1959); Manning v. Board

of Public Insturction of Hillsboro County, 277 F.2d 370 (5th

cTr. ,~1960) ; Dove vT parham7~~282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir., I960) .

9

worked the same way — so-called free choiceT-

Permitting students to assign themselves under free choice

produced a greater administrative difficulties than normal methods

of pupil assignment. in Moses v. Washington Parish School Board. 276

F. Supp. 834 (E.D. La. 1967), the Court observed:

Free choice systems, as every southern

school official knows, greatly complicate

the task of pupil assignment in the system

and add a tremendous workload to the alreadv

overburdened school officials. Y

* * *

If this Court must pick a method of assigning

students to schools within a particular school

district, barring very unusual circumstances,

we could imagine no method more inappropriate,

more unreasonable, more needlessly wasteful~in

every respect, than the so-called' "-Fr-oo 'Choice»

system. (Emphasis added.) (id at 848, 851).

Given the administrative difficulties of free choice and given

the plain fact that it placed on the shoulders of Negro students a

burden which was rightly the Boards' — why did it achieve such

Ij-/ According to the Civil Rights Commission, the vast majority

of school districts in the south use freedom of choice plans.

See Southern ScIiqq I Desegregation, 1966-67, A Report of the

at p p ^ l f 011 °n CiVil RightS' July 1967* The rep°rt states,

Free choice plans are favored overwhelmingly by the

1,787 school districts desegregating under voluntary

pt^-ns. All such districts in Alabama, Mississippi,

and South Carolina, without exception, and 83% of

such districts in Georgia have adopted free choice plans. . . .

The great majority of districts under court order

also are employing "freedom of choice."

See also Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-1966, United States Commission on Civil

Rights, February, 1966, at p. 47.

10

widespread use? The opinions by and large do not deal with the

question at all. It remained largely ignored until The Washington

parish case. But the answer is plain: School boards generally, and

these boards in particular, adopted and seek to maintain free

choice because it is the method most likely to maintain the status

quo: racially separate schools. They know full well that only a

few Negro students will choose white schools and that white students

12/

will never choose Negro schools. And, indeed, none have ever done

so in any of these parishes in the more than four years of free

choice. Most importantly, they know that more rational methods of

pupil assignment -- i.e., by zoning and/or pairing — would, because

of the lack of residential segregation, produce immediate and total

integration of the races, and that is the last thing they want.

One non-lawyer has put it extremely well:

Freedom of choice. . . has not brought significant school

desegregation. . . simply because it is a policy which has

proved too fragile to withstand the political and social forces

of Southern life. The advocates of freedom of choice assumed

that school desegregation would somehow be insulated from

these forces while, in reality, it was central to them.

In embracing the freedom of choice plan Southern school

systems understood, even if HEW did not, that man's choices

are not made within a vacuum, but rather they are influenced

by the sum of his history and culture. M. Hayes Mizell, The

South Has Genuflected and Held on to Tokenism, Southern

Education Report, Vol. 3, No. 6 (january/February 1968) at

p . 19.

11

II

Appellees May No Longer Constitutionally

Assign Students Pursuant to Their Choice

a . Jefferson

In Jefferson II, this Court proclaimed that school officials

in this circuit (380 F .2d 385, 389):

have the affirmative duty under the

Fourteenth Amendment to bring about

an integrated unitary school system

in which there are no Negro schools

and no white schools -- just schools.

While it did so in the context of approving the continued use of

free choice (but under much more stringent conditions), the Court

made it plain that "the only school desegregation plan that meets

constitutional standards is one that works" (Original emphasis)

Jefferson I, 372 F.2d at 847; and it gave notice that if freedom

of choice failed, other methods would have to be employed:

If the [freedom of choice] plan is

ineffective, longer on promises than

performance, . . . school officials

. . . have not met the constitutional re

quirements of the Fourteenth Amendment;

they should try other tools. Jefferson II,

380 F .2d at 3 90.

The plans in this case have clearly been ineffective. In only

one of these Parishes are more than 6% of the Negro students en

rolled in previously white schools: and even there, Iberville,

it is only 9.8%. In none of the Parishes has a single white child

ever attended a Negro school. Thus, 15 years after Brown, and four

and sometimes five years after the adoption of free choice, more

than 90% of the Negro children in these Parishes still attend all-

Negro schools. How much more ineffective can desegregation plans

be? Unless the quoted language in Jefferson is to be rendered

12

entirely nugatory, it must in these circumstances require the

development of alternate plans. Jefferson alone, we submit,

would require — - without reference to the later cases — that the

decision below be reversed,

b. Green and Greenwood

Applying standards developed in the cases since Jefferson,

reversal is even more dear. In Green v. County School Board of

New Kent County, va., 391 U.S. 430, the court formulated a more

stringent rule. There, the question was whether a school district

could utilize free choice where Negroes and whites resided all over

the County and where the free choice plan had resulted in the

enrollment of only 15% of the Negro students in white schools, and

no white children in Negro schools. The Supreme Court declared the

plan unconstitutional. Said the court (391 U.S. at 441):

The New Kent School Board's 'freedom of

choice' plan cannot be accepted as a

sufficient step to 'effectuate a

transition' to a unitary system. In

three years of operation not a single white

child has chosen to attend [the Negro

school] and. . . 85% of the Negro children

in the system still attend the all-Negro

Watkins School. In other words, the school

system remains a dual system.

It framed the governing principle this way:

[Freedom of choice must be held unacceptable]

. . . if there are reasonably available other

ways, such for illustration as zoning,

promising speedier and more effective conver

sion to a unitary, nonracial school system.

It emphasized that the "time for deliberate speed had run out"

and that conversions to unitary systems must be made "now" (Id at

438-9); finally it defined the affirmative duty to be "to take

13

whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch"

(Id at 437-8).

All of defendant districts have utilized some kind of free

choice plan for at least four years -- longer than in New Kent.

Yet they all maintain (and will continue to maintain if permitted

to retain it) schools plainly identifiable as 'white' and others

as 'Negro.' Since none have even come close to achieving the 15%

transfers by Negro students to white schools, which has been declared

insufficient, it would hardly seem debatable that they should be

required to develop other methods.

Significantly, the Green test is not whether free choice is

working to produce some desegregation, but whether other methods

promise to work better. The court below, in keeping with its view

of the issue, did not even consider whether any alternative to free

choice would more effectively dismantle the dual system. Although

conceding that the dual system had not been disestablished, the

Court did not require the submission of alternatives. Given the

dismal performance of free choice, that failure alone made it

error, to approve its continued use.

The record shows that other methods promising speedier conversions

do exist. And, in fact, alternate proposals of the United States

were put to each of the Superintendents during the depositions.

Under either plans of zoning and/or pairing, all children in each

of these districts would attend school with children of the other

race. There simply is no significant residential segregation in

14

t

these parishes. We reemphasize again that defendants seek so

passionately to retain free choice only because more rational

methods of pupil assignment would, because of the lack of

residential segregation, produce immediate and total integration

of the races.

The opinion of this Court in United States v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School District, ___ F. 2d ____ , No. 25714,

February 4, 1969 seems conclusively to require reversal of the

decision below. There the free choice plans, had, after three

years of operation resulted in only 1.8% of the Negro students in

white schools and no white students in Negro schools. Said the

court (slip op. 12):

Looking at these enrollment figures

for the two previous school years,

we cannot escape the conclusion that

freedom of choice has not been

successful in bringing about a

transition to a unitary nondiscriminatory

school system.

* * *

The statistical showing in Greenwood

has been much worse [than in New Kent];

therefore freedom of choice must be

abandoned in favor of some other plan. . .

Evaluating results from the perspective of the percentage of Negro

children still in all-Negro schools, the same decision is required

in all these cases, unless, that is, the difference between 90.2%

15

13/

and 98.2% is deemed significant.

G * Continuation of Racially Identifiable Schools

Other decisions of this Court construing Green also require

reversal. Well in advance of the decision below, this Court;

in Adams v. Mathews, supra, interpreted Green to require and

directed the districts courts to apply, the following rule:

If in a School district there are still

all-Negro schools, or only a small fraction

of Negroes in white schools, or no

substantial integration of faculties and

school activities then, as a matter of law,

the existing plans fail to meet

constitutional standards as established in

Green. (Emphasis added.) (403 F.2d 181, 188)

In subsequent cases the court reaffirmed its ruling that all all-

Negro schools must be eliminated (by closing or by the assignment

of white pupils) by the start of the 1969-70 school year. See

14/Graves v. Walton County Board of Education, 403 F.2d 189; United

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, f .2d

_________ No. 25714 (5th Cir. February 4, 1969) ; and in Henry v.

Ciarksdale Municipal Separate School District, No. 23255, ___

F . 2d _______ (March 6, 1969) the court repeated (at slip op 16)

13 / 90.2% is that achieved in Iberville Parish — the "best"

of those before the Court; 98.2% was the figure in Greenwood.

The performance in Livingston parish is even worse than in

Greenwood. There 99.6% of the Negro students are still in

all-Negro school and that was higher than the previous year.

14/ In Graves the court stated (403 F.2d 189,):

In its opinion of August 20, 1968, this

Court noted that under Green (and other cases),

a plan that provides for an all-Negro school

is unconstitutional.

It added that the all-Negro schools in this circuit:

Are put on notice that they must be

integrated or abandoned by the commence

ment of the next school year. . . .

(Emphasis added.)

1 6

verbatim the sentence from Adams v. Mathews, quoted above.15/

Incredibly the district court's opinion makes no reference at

all to the principles enunciated in Adams and Graves, although, as

evidenced by the briefs below, they were brought forcefully to his

attention. His decision effectively ignores them; for, as shown by

the table on p. 5, supra, free choice has permitted, in each of

these Parishes the continuation of several all-Negro schools. There

is no claim either by the boards or the court that they will be

eliminated in the forseeable future much less by Fall 1969. Thus,

because free choice promises to continue Indefinitely these all

Negro schools the district court erred in approving its continued use.

The district court was obliged to require each Parish to

devise new methods of pupil assignment which would immediately

eliminate all such schools either by the abandonment of the

facility or by the assignment thereto of substantial numbers of

white children. As we have previously indicated such plans are

possible and do, in fact, exist. (cf. pp. 4-5 supra).

To be sure it may be argued that Green does not by its terms

require the elimination of all all-Negro schools. But, we submit,

the cases announcing that rule correctly interpret Brown and Green.

15/ In Greenwood, the Court said (slip op. 14):

"We do say that a new plan must be devised to

eliminate the remaining, glaring vestige of a

dual system: the continued existence of all

Negro schools with only a fraction of Negroes

enrolled in white schools."

17

Brown condemned not only compulsory racial assignments

but also, more generally, the maintenance of a dual public

school system based on race — where some schools are maintained

or identifiable as being for Negroes and others for whites. It

presupposed major reorganization of the educational systems in

affected states. The direction in Brown II, to the district courts

demonstrates the thoroughness of the reorganization envisaged.

They were held to consider:

problems related to administration, arising

from the physical condition of the school

plant, the school transportation system,

personnel, revision of school districts and

attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a non-racial basis, and revision of

local laws and regulations which may be necessary

in solving the foregoing problems (349 U.S. at

300-301). 16/

If a "racially non-discriminatory system" could be achieved

with Negro and white students continuing as before to attend schools

designated for their race, none of the quoted language was necessary.

It would have been sufficient merely to say "compulsory racial

assignments shall cease." But the Court did not stop there. It

ordered, rather, a pervasive reorganization which would transform

the system into one that was "unitary and non-racial," one, in other

words, in which schools would no longer be identifiable as being for

Negroes or whites.

Much the same was implied in Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at 358

U.S. 7: "state authorities were thus duty bound to devote every

effort toward initiating desegregation. . ."

1 6 /

#

Hie only way the racial identification of a school — consciously

imposed by the state during the era of enforced segregation — ■ can be

erased is by having it serve students of both races, through teachers

of both races. Only when racial identification of schools has thus

been eliminated will the dual system have been disestablished.

The court in Green recognized the importance of eliminating

identifiable Negro and white schools. It observed that:

the fact that in 1965 the Board opened

the doors of the former "white" school

to Negro children and of the "Negro"

school to white children merely begins,

not ends, our inquiry whether the Board

has taken steps adequate to abolish its

dual, segregated system.

Finally, echoing this court in Jefferson, it directed the Board to

fashion steps to convert to a system without a "white" and a "Negro"

school, but just schools.

Even before Green the Eighth Circuit had intimated that view of

Brown. Thus, in Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178, 183 (8th Cir, 1968),

the court said;

Perpetuation of this all-Negro school

in a formerly de_ jure segregated school

system is simply constitutionally

impermissible.

And in Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22,

378 F .2d 483, 490 (8th Cir. 1967):

The appellee school district will

not fully be desegregated nor the

appellants assured of their rights

under the Constitution so long as the

Martin School remains identifiable as a

Negro school.

19

In sum, we submit that the decisions of this Court

interpreting Brown and Green are eminently correct and require

the reversal of the decision below.

d. Some Observations on the District Court's Opinion

The court's opinion is composed of so many divergent strands,

most of which are legally erroneous, that it is difficult, if not

impossible, to draw from it a rational, consistent and cohesive

line.

The fundamental error the court made, however, is in its

misreading of Green. It ruled that (slip op. 7).

If a school is, in fact, attended solely

by Negro children or solely by white

children as a result of a bona fide,

unfettered freedom of choice, the

segregation that thus resuits is not state

imposed but is instead de facto segregation.

The court is obviously mistaken; moreover, there is no support,

legally or sociologically, for that conclusion. The Supreme Court

ruled precisely the reverse. The law had already been that free

choice was improper if conducted in an atmosphere of fear, threats

of intimidation and reprisals. See Coppedge v. Franklin County

Board of Education, 273 F. Supp. 289, affirmed 394 F, 2d 410 (4th Cir.

1968); Cf. Jefferson I, 372 F.2d at 889.

The question in Green was what if an "unrestricted and

unencumbered" (the Fourth's Circuit description) free choice plan

still failed to effect desegregation. The court answered that plainly

by saying that the Board there had not discharged its responsibilities

that it must use other methods, and, prescribed a new rule: that

free choice could not be used at all if other methods would effect

greater integration.

20

Finally, in no case has segregation resulting from the

failure of children to choose schools theretofore identified for

the other race been termed "de facto." Such segregation, rather,

is the result of the failure to disestablish what has previously

been state imposed.

17/

The other ground of the decision is equally incredulous.

In the first place the court states that "there is no evidence in

the record that students failing to choose were assigned to the

nearest school"; of course, there is not; the reports required by

the Jefferson decree did not require that such assignments be

separately reported or enumerated. Put another way, it is not

possible for the district court to tell what was done with such

pupils. Thus, it was error to have asserted that as a ground

for the decision.

More importantly, however, the attorneys in this case had no

notice at all that the judge was concerned about compliance with

that provision. It was not discussed at either the July 19th or

November 4th hearing and its advancement for the first time here

comes as a complete surprise. If the court was concerned why did

he not instruct counsel to develop evidence on the point? Was it

5% or 50% of the children that failed to choose? This was obviously

critical to the issue whether if it were complied with, free choice

would succeed. None of the briefs below discussed these questions.

17/ The other ground, see p. 6 , supra, was that the plan had not

worked because some of the boards had failed to assign children

failing to choose to the geographically nearest school, and, if

they had, all constitutional requirements would be satisfied.

21

Having armed himself with this spurious basis for decision,

the lower court stands free choice on its head. Emphasizing the

critical nature of the "ommission", he concludes:

to ignore the geographic assignment

provision of the plan largely defeats

the purpose of the plan (slip op. 10).

But that is disingenuous. The point of the free choice Jefferson

decree was to encourage all students to exercise their choice.

While it was hoped that the overwhelming majority would do so, it

was nontheless recognized that a few would not and it was to those

few that the provision in question was directed.

As we have said it was impossible to tell (1) whether the

boards complied or (2) even if they did not, the extent of the

harm caused thereby. Under these circumstances it was error to

approve its use for that reason.

Finally the court suggested that since the Jefferson free choice

plan had been in effect for only a year, it had not had an

18/opportunity to prove itself. That approach, of course, suggests

gradualism and ignores the Supreme Court's directive that the time

is now. More importantly, however, it avoids the critical issue.

The fact is that these boards have for some four or five years

permitted children to assign themselves. While Jefferson effected

a change to a system in which each child would exercise a choice

rather than just those seeking transfers, its success nonetheless

depends upon the same phenomenon: the willingness of Negro children

to assign themselves voluntarily to white schools and, more

importantly, the willingness of white children to do the same

regarding Negro schools. But that will not happen. The reality

18/ The Court is mistaken. They have twice conducted free choice periods under Jefferson standards. The first was following the

entry of the Jefferson Decree in August, 1967. The second was

in March 1968.

22

is that only a few, if any, Negro students will choose white schools,

and white students will never choose Negro schools. That being

the case, given the customs and habits in these Parishes, no system

in which assigrmarts are based entirely upon the choices of students

will ever succeed. And the record of the last five years amply

demonstrates that fact.

Ill

THIS COURT MUST PRESCRIBE PROCEDURES GUARANTEEING

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF OTHER PLANS BY THE OPENING

OF THE 1969-70 SCHOOL Y E A R . _____

The history of these cases and indeed, all the school deseg

regation cases in the Baton Rouge Division of Eastern District of

Louisiana underscores the importance of this Court's insuring that

its orders will be observed. In the face of Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F 2d 729 (June 22, 1965),

which decreed that at least four grades were to be desegregated

in Fall 1965, the Court below entered (July 8, 1965) orders pro

viding for the desegregation of only two and on July 30 denied

motions to conform them to Singleton In the face of Jefferson

I 's declaration that "The decree [was] to be applied uniformly

throughout this circuit . . . " (372 F.2d at 894), the lower court

lg/ See July 8 and July 30, 1965 orders in the Pointe Coupee

and Livingston Parish cases.

f

allowed inter alia, the continuation of initial race assignments

2 0/

with transfers out and was summarily reversed. In the face of the

clearest possible language in Adams v. Matthews, and Green it

permitted the continuation of free choice in circumstances obviously

violating the Constitution as interpreted in those cases.

This pattern is not of recent vintage. As early as 1963

Negro litigants in school desegregation cases have been aware that

Judge West would comply with orders of this Court only under sus

tained and unremitting compulsion. The same conclusion was reached

by this Court in Hall v. West, 335 F.2d 481 (5th Cir. 1964). There

Judge West had for several years refused to enter an order requiring

desegregation of St. Helena Parish Schools, albeit the suit had

been filed prior to Brown. In its opinion granting a writ of

mandamus directing him to enter such an order, this Court said:

There would appear to be little to be gained

if we were to restrict our order to a require

ment that the trial court make a judgment in

the matter, without directing the nature of

the judgment to be entered. The respondent has

had ample admonishment, both from the Supreme

Court and this Court, as to what is required of

him in the premises. His failure to respect

these admonishments makes it reasonably clear

that an order from us directing merely that he

enter a judgment in the case would mean simply

that the case would be back here again because

of his clear indication that he does not pro

pose to enter the proper order until directed

to do so. Such further delay and such further

consumption of judicial time is not only unneces

sary but it would tend to destroy the confidence

of litigants in our judicial system.

Id at 485.

20/ Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, No. 25092, August 4, 1967.

2 4

Each of the most recent refusals described above has had a

direct impact on the progress - or lack of it - toward a unitary

system. Thus in 1967 the mandatory choice period was not instituted

until August because of the necessity to come to this Court for

relief. So too the failure to follow Green in July 1968 meant the

needless loss in all the districts - most of which are very small —

of yet another school year.

Where will this end? Sooner or later this Circuit must face

the fact that the segregation that still characterizes most school

districts in the South is due in large part to the refusal of dis

trict judges to meet their responsibilities. It is not enough to

blame school boards. They believe they have a constituency —

the white majority — and that they are duty bound to carry out

its wishes, which have been to preserve the status quo. The plain

fact is that school boards in this circuit, and certainly in

Louisiana, are going to take no steps promising seriously to bring

about integration except under the compulsion of a court order.

And neither avowals of, nor appeals to, "good faith" will change that.

The burden then — if real change is to be effected — has always

been and still is on the local district judge. It is his willing

ness to insist that the decisions of higher courts be implemented,

which will determine whether Brown will be complied with.

The record of the district court in these cases suggests that

absent the clearest possible instructions from this Court —

appellants will lose the 1969—70 school year. Hearings on remand

25

will be delayed, unduly long time given the Boards to devise

alternative plans, the wait for a decision etc. It should not go

unnoticed that the district court solemnly stated "freedom of

choice must simply be preserved" (slip op.).

Under these circumstances, we believe it absolutely necessary

for this Court to remand these cases to the district court with

at least the following instructions:

1. To enter, immediately upon the issuance of the mandate,

and without scheduling a further hearing, an order:

(a) prohibiting the assignments of students for

the 1969-70 school year pursuant to their choices;

(b) directing each board to file within two weeks

from the date of the order, a plan for the assign

ment of all pupils for the 1969-70 school year by

means of geographic attendance zones and/or by the

pairing of schools;

(1) the plan must be devised in such manner

that no school shall be attended only by Negro

students; to achieve that end the plan shall

provide for the assignment of substantial

numbers of white children to previously Negro

schools, or, where a particular facility is

inadequate, that it be closed;

2 6

(2) each plan shall contain a sheet listing

all schools, which sheet shall state in tab

ular form, the grades it will serve and the

number and percent of white and Negro students

to be enrolled in each grade of each school;

(c) directing each Board to file, no later than

four weeks therefrom, a plan for the assignment of

teachers, as well as principals, assistant principals

and supervisory personnel on a non-discriminatory

basis, based on the plan for the assignment of

students. The plan for teacher assignments shall

be so devised that the ratio of white and Negro

teachers in each school shall approximate the ratio

21/

of such teachers in the entire system;

21/ We have not discussed faculty desegregation herein, only because

of the press of time under which this brief is being prepared and

because the issue of students is more directly involved. Examination

of the data in the record will reveal that faculty desegregation has

barely begun. See the summaries of the relevant statistics contained

in the appendix to the brief for the United States. That aspect of

the desegregation plan must obviously be dealt with.

In West Baton Rouge, only 13 of some 125 white teachers are

assigned to Negro schools, and only 12 of 122 Negro teachers are

assigned to previously white schools. These figures do not include

itinerant teachers. See Report to Court Filed September 18, 1968.

27

f r

2. That plaintiffs shall have five days to file amendments

or objections to the proposed plan regarding students; that, in

the event no objections are filed, the plan shall thereupon be

approved if it otherwise meets the standards prescribed in Adams

v . Matthews and other cases;

3. Where objections or amendments are filed, a hearing

shall be conducted thereon within fifteen days from the filing

thereof;

4. That school desegregation cases are entitled to the high

est priority and that any adjustments in the scheduling of other

cases shall immediately be made, where such adjustments are necessary

to ensure the orderly implementation by Fall 1969, in each of these

districts, of the new zoning and pairing plans.

Wherefore for the foregoing reasons it is respectfully

submitted that the judgment below be reversed and the cases re

mended with the instructions suggested above.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

FRANKLIN E. WHITE

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A .P . TUREAUD

A.M. TRUDEAU, JR.

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

upon counsel for defendants and intervenor, toy United States

mail, postage prepaid, as follows:

The Honorable Jack P. F. Gremillion '7

Attorney General of Louisiana

State Capitol Building

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70804

John F. Ward, Esq.

206 Louisiana Avenue

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

70802

HarryJ. Kron, Jr., Esq.

202 Audubon Street

Thibodeaux, Louisiana 70301

The Honorable Thomas McFerrin

Assistant Attorney General

/ State of Louisiana

> State Capitol Building

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The Honorable Samuel C. Cashio

District Attorney

18th Judicial District

Plaquemine, Louisiana 70764

f" The Hon. Leonard Yokum

District Attorney

21st Judicial District

Amite, Louisiana 70422

Hugh W. Fleischer, Esq.

Joseph Ray Terry, Jr., Esq.

Department of Justice

Masonic Temple Building

Room 1723

333 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

70130

The Honorable Aubert D. Talbot

/ District Attorney

23rd Judicial District

Napoleonvilie, Louisiana 70390

The Honorable Jerris Leonard

The Honorable Myrle Loper

United States Dept, of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Washington, D. C.

Attorney for Appellants

RECORD PRESS, INC. — 95 Morton Street — New York, N. Y. 10014 — (212) 243-5775

38