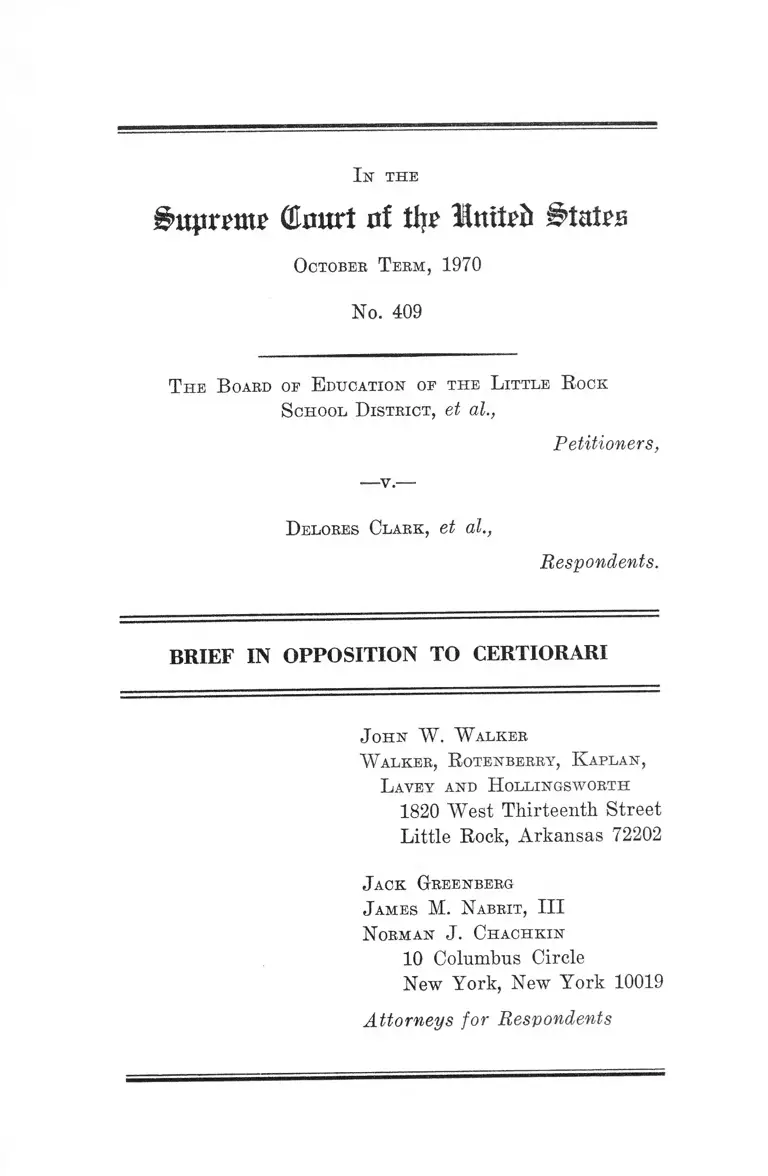

The Board of Education of the Little Rock School District v. Clark Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The Board of Education of the Little Rock School District v. Clark Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1970. dec23b6d-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/75444a40-c59e-4c71-92b4-1f67e882687b/the-board-of-education-of-the-little-rock-school-district-v-clark-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(ta rt nf % lntiT& States

O ctober T e e m , 1970

No. 409

T h e B oard of E d u c a t io n of t h e L it t l e R ock

S c h o o l D ist r ic t , et al.,

Petitioners,

-v -

D elores Cl a r k , et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J o h n W . W a l k e r

W a l k e r , R o t e n b e r r y , K a p l a n ,

L a v e y a n d H o l l in g s w o r t h

1820 West Thirteenth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

J a c k G reenberg

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions B elow ............. .......... .............. ....... 1

Jurisdiction .... 2

Questions Presented ................................... 2

Statement .............................................................................. 3

The Little Rock School District ................ 6

The Oregon and Parsons Plans ............................... 9

Development of the Plan Rejected by the Court

of Appeals ....... 11

Alternatives Available to the District ............ 16

A rgument ...................................................................... 19

Conclusion ........................................................... 26

A p p e n d ix :—

Defendants’ Exhibit 24 .............................................. la

Defendants’ Exhibit 25 .................................. 2a

Defendants’ Exhibit 8 ................................................ 4a

Defendants’ Exhibits F and G- ............................. 6a

Exhibit H ...................................................................... 8a

PAGE

11

T able oe C ases

page

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956),

aff’d 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957); 2 Race Eel. L. Rep.

934-36; 938-41 (E.D. Ark. 1957), aff’d 254 F.2d 808

(8th Cir. 1958); 156 F. Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark. 1957),

aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797

(8th Cir.), aff’d 358 U.S. 1 (1958), 261 F.2d 97 (8th

Cir. 1958); 169 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark. 1959) ....1, 2, 4, 5

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark. 1958),

cert, denied 357 U.S. 566 (1958) was reversed 257

F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958), aff’d sub nom. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ...................................... ....... 4

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.),

aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959) 2, 5

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark. 1960),

rev’d sub nom. Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798

(8th Cir. 1961) ...... ............................................... ....... 2, 5

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .................................................................. 24

Andrews v. City of Monroe, No. 29358 (5th Cir., April

23, 1970) ......... ................................................................ 21

Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ. and Thomie v.

Houston County Bd. of Educ., No. 29,121 (5th Cir.,

Feb. 5, 1970) .................................................................. 20

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Va.,

No. 14,544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970) cert, denied 38

U.S.LAV. 3522 (June 29, 1970) ............................. 20,21

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....4, 24, 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) .... 4

Byrd v. Board of Directors of Little Rock School Dist.,

Civ. No. LR 65-C-142 (E.D. Ark. 1965) ................... 9

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S.

940 (1967) ........................................................................ 23

I l l

Christian v. Board of Education of Strong, Civ. No.

ED-68-C-5 (W.D. Ark., Dec. 15, 1969) ................. ..... 24

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Bock School

District, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966) ...............1, 2, 5, 8

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................... 4

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s of Mobile, No. 436

O.T. 1970 .......................................................................... 22

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734, 742 (E.D. Mich. 1970) .......................................... 25

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

423 F.2d 203, n. 7 (5th Cir. 1970) ............................... 21

Graves v. Board of Educ. of North Little Rock, C. A.

No. LR-68-C-151 (E.D. Ark.) ...................................... 20

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) .......................................... 5, 22, 23

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.) cert, denied, 396 U.S.

940 (1969) ..... 22

Hilson v. Ouzts, No. 28491 (5th Cir., April 3, 1970) .... 20

Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, 416 F.2d 380

(8th Cir. 1969) ............................................................. 22

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Educ. of Nash

ville, Civ. No. 2094 (M.D. Tenn., July 16, 1970) ....... 23

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, No. 28643 (5th Cir., May 11, 1970) .... 22

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson, No. 19720

(6th Cir., June 19, 1970)

PAGE

23

IV

Northcross v. Board of Education of the Memphis City

Schools, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) ...................................... 20

Safferstone v. Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W. 2d 3

(1962) ............... - ......................................................... .... 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No.

14.517 (4th Cir., May 26, 1970), cert, granted on

other issues, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522 (June 29, 1970) .......21, 22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No.

14.517 (4th Cir., May 26, 1970) cert, granted on

other issues, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522 (June 29, 1970) .......21, 22

United States v. Board of Educ., Independent School

Dist. No. 1, Tulsa, No. 338-69 (10th Cir., July 28,

1970) ....... .......... .......... ....................... -........................... 20

United States v. State of Georgia, No. 29067 (5th Cir.,

June 18, 1970) ................................................................ 20

PAGE

S t ate S t a t u t e s

Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.A. §§3601 et seq.

(Supp. 1970) .................................................................... 25

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors, 233 (1955) ................... 25

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 201-02, 254, Legal

Appendix at 255-56 ........................................................ 25

Race and Place—A Legal History of the Neighborhood

School, Weinberg, (U.S. Gov’t Printing Office, Cat

alogue No. FS 5.238:38005, 1967) ................................ 19

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto, 71-73 (1948) ...................... 25

Is- THE

dttprem? Qlmtrt of % Initrd BtnUs

O ctober T e r m , 1970

No. 409

T h e B oard oe E d u c a t io n of t h e L it t l e R ock

S ch o o l D ist r ic t , et al.,

Petitioners,

-v.-

D elores Cl a r k , et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals issued May 13, 1970,

of which review is sought by Petitioners, is not yet re

ported; it is appended to the Petition at pp. A -l to A-25.

The opinion of the district court was unreported and

appears as an Appendix to the Petition, pp. A-27 to A-57.

Prior reported opinions in this case and its predecessor

action1 appear as follows: Aaron v. Cooper, 143 P. Supp.

855 (E.D. Ark. 1956), aff’d 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957);

1 The district court and the Court of Appeals recognized that

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Bock was but the continuation

of the original Aaron v. Cooper suit brought in 1956 to desegregate

the Little Rock public schools. See Joint Appendix below, at p. 7;

Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, pp. A-2 to A-3.

2

2 Race Eel. L. Rep. 934-36; 938-41 (E.D. Ark. 1957), aff’d

254 F,2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958); 156 F.Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark.

1957), aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d

797 (8th Cir. 1958); 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark), rev’d 257

F.2d 33 (8th Cir.), aff’d 358 U.S. 1 (1958); 261 F.2d 97

(8th Cir. 1958); 169 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark. 1959); Aaron

v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.), aff’d sub nom.

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959); Aaron v. Tucker,

186 F. Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark. 1960), rev’d sub nom. Nor

wood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961); Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966).

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional prerequisites are adequately set forth

in the Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

Questions Presented

Respondents are unable to agree that the five “ Questions

Presented” in the Petition for Writ of Certiorari at pp.

4-5 appropriately describe the issues posed by this litiga

tion. Each of the “ Questions Presented” described by Peti

tioners assumes “fairly drawn attendance zones” although

respondents contended, and the Court below found, that

in the context of the forms discrimination and school seg

regation took in Little Rock, the school board’s zoning plan

was not fairly or constitutionally drawn.

The following statement of the Questions Presented is

adapted from Respondents’ brief in the Court of Appeals:

1. Does a school district formerly segregated by law

fulfill its constitutional obligation to convert to a uni

tary system by adopting an assignment plan which

conforms to racial residential patterns and which fails

3

to appreciably alter the pattern of racially separate

school attendance characteristic of the dual system?

2. Can such an assignment plan be justified on the

ground that it is a “ neighborhood school” plan where

the school district formerly assigned students to

schools outside their “neighborhoods” in order to pre

serve segregation?

3. Can such an assignment plan be justified on the

ground that changing the segregated attendance pat

terns in the public schools of the district may require

the expenditure of funds to provide pupil transporta

tion?

Statement

The Petition for Writ of Certiorari does not contain a

reasonably detailed statement of the facts, the pleadings,

or the desegregation plans presented to the district court;

petitioners do not substantially rely upon the facts of rec

ord as grounds for review. Yet the decision of the Court

of Appeals is founded upon an assessment of the practical

effects of the zoning plan in the light of the history of

desegregation or the lack thereof, in this district since

1954, and not upon abstract discussions of “racial balance.”

See Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, pp. A-13,

to A-16. Accordingly, and in view of the lengthy record,

we think it appropriate to make available to the Court the

following detailed recitation of the facts adapted from our

Brief in the Court of Appeals.2

2 We have also reprinted as an Appendix to this Brief some of

the trial exhibits reprinted in our Court of Appeals brief. The

parties agreed that the joint Appendix would contain only the

pleadings and the transcript but that either party might put before

the Court of Appeals in the form of an appendix to its brief, such

trial exhibits as it desired.

4

The current proceedings3 were formally commenced in

Juy 1968 with the filing of a Motion for Further Relief

3 After Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the Little

Rock school board adopted a plan of very gradual integration.

When that plan was not implemented, Negro students and their

parents brought suit in 1956. The initial plan, calling for complete

desegregation by 1963, was approved by the district court that

year, Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956). The

Court of Appeals rejected arguments that more rapid desegrega

tion should be required, in part for the reason that the first plan

had been voluntarily adopted by the school board even before the

second Brown decision (Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294

(1955)). Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957). Subse

quently, when white parents obtained a state injunction to prevent

implementation of the plan in 1957-58, the district court restrained

compliance with the order of the Arkansas court and mandated

execution of the plan. Aaron v. Cooper, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 934-36,

938-41 (E.D. Ark. 1957), aff’d 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958). The

Governor of Arkansas then took measures to prevent Negroes from

attending classes at the previously-white Central High School, in

cluding the stationing of National Guardsmen with fixed bayonets

at the school with orders to prevent the entry of Negro students.

This conduct was enjoined in Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220

(E.D. Ark. 1957) aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d

797 (8th Cir. 1958). However, intervention by federal troops under

direct order of the President of the United States was required to

effectuate compliance with the district court’s orders and with

the Constitution. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 12 (1958).

After the conclusion of the 1957-58 school year, the board sought

to delay implementation of the plan for at least three additional

years because of the extent of white opposition to integration. The

district court’s order approving a delay, Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F.

Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark. 1958), cert, denied, 357 U.S. 566 (1958), was

reversed, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958), aff’d sub nom. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

Pursuant to emergency measures passed by the Arkansas Legisla

ture in special session, the Governor of Arkansas then ordered all

Little Rock high schools [the desegregation plan at that time ex

tended only to the high school grades] to be closed indefinitely.

Thereupon, the board undertook to lease its high school buildings

to a segregated private school corporation. The district court denied

an injunction against the leasing of the facilities, but the Court of

Appeals reversed and required issuance of the decree, Aaron v.

Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958). However, Little Rock public

high schools remained closed during the 1958-59. school year, see

5

based upon Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and companion cases.

In that Motion (A. 5a-14a),4 plaintiffs sought—and plain

tiff--intervenors sought in their Complaint (see A. 27a-31a)

—an order requiring the Little Rock School District to

abandon its free choice plan of desegregation and to adopt

and implement a plan of desegregation which “promises

realistically” to convert now to a unitary school system.

Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark. 1959), until the

Arkansas school closing legislation was declared void by a three-

judge district court in Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D.

Ark. 1959) (per curiam), aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S

197 (1959).

The board then assigned pupils during the 1959-60 school year

on the basis of regulations adopted by it pursuant to the Arkansas

Pupil Placement laws, which required consideration of a. multitude

of factors other than residence (e.g., “ the possibility of breaches of

the peace or ill will or economic retaliation within the community” ).

An attack upon these laws was rejected by the district court,

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark. 1960), but its judg

ment was reversed in Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798, 802 (8th

Cir. 1961), where the Court said, “ [wjhile we are convinced that

assignment on the basis of pupil residence was contemplated under

the original plan of integration, it does not follow that the school

officials are powerless to apply additional criteria in making initial

assignments and re-assignments.” The board’s use of the pupil

placement laws was “motivated and governed by racial considera

tions,” id. at 806, said the Court, and the board’s “obligation to

disestablish imposed segregation is not met by applying placement

or assignment standards, educational theories or other criteria so

as to produce the result of leaving the previous racial situation

existing as it was before.” Id. at 809.

The Clark plaintiffs in 1965 complained of continued manipula

tion of the Pupil Placement laws to limit the movement of Negroes

into previously all-white schools. The district court so found. See

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Bock, 369 F.2d 661, 665 (8th

Cir. 1966). While the district court’s opinion in that case was being

prepared, the board determined to abandon the Pupil Placement

laws in favor of a “freedom of choice” plan, subsequently approved

by the district court and by the Eighth Circuit with certain di

rected modifications. Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Bock, supra.

4 Citations are to the Joint Appendix below.

6

After further proceedings, the district court approved a

geographic zoning plan submitted by the board.

The Little Rock School District

At the present time there are five high schools, seven

junior high schools, and thirty-one elementary schools

(Defendants’ Exhibit No. 24, p. la infra)* 6 in the Little

Rock School District, which served an estimated 1969-70

student enrollment of 15,377 white students and 8,281

Negro students (Defendants’ Exhibit No. 25, p. 3a

infra). As the Court of Appeals noted in its opinion (See

Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, p. A-6), the

district generally forms an irregular rectangle with the

longer side running from east to west along the Arkansas

River. The most prominent exception to this pattern is

the extension of the district in two finger-like projections

at its northwest end. These have resulted from the district’s

annexation, since 1956, of the white residential subdivisions

of Walton Heights and Candlewood. Between the two “ fin

gers” lies a Negro residential area known as Pankey (A.

485-589).

Since 1956 the district has expanded almost exclusively to

the west.6 Of thirteen new school facilities opened since

6 See note 2 supra.

6 Expansion of the district has not benefited both white and Negro

citizens of Little Rock. Various urban renewal projects since 1954

have eliminated areas of Negro residences near the present Hall

High School (A. 289), and in Pulaski Heights (A. 290-91). Of

more than one hundred and seventy-five subdivisions developed in

Little Rock between 1950 and 1968 (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 4), only

two— Granite Mountain and University Park—have Negro res

idents (A. 746). On the other hand, William Meeks, a member

of the Little Rock School Board and Little Rock “Realtor of the

Year” in 1967, testified of discrimination against Negroes in the

sale of housing (A. 743-44). He said that he knew of no Little

7

that year, only three have been located in the east-central

section of the city: Booker Jr. High, Ish and Gillam Ele

mentary Schools. All were named for prominent Negroes

(A. 473, 482); all were initially opened as Negro schools

(A. 473, 477, 482) with all-Negro faculties {Ibid).

On the other hand, the district built nine schools7 in West

ern Little Rock between 1956 and 1969: Parkview High

School, Henderson Junior High and Southwest Junior

High Schools, Bale, McDermott, Romine, Terry, Western

Hills and Williams Elementary Schools. In each instance,

these schools were initially filled with an all-white faculty

(A. 154) and they have remained identifiable as “white”

schools.

The district court accepted “as obvious the proposition

that the Little Rock District located new schools in the

center of concentrations of one race and limited the capac

ities of those schools to service only that particular com

munity” (A. 155-56). Faculty assignments to these schools

were then based on the racial composition of the neighbor

hood (A. 153). Schools built since 1956 have been either

nearly all-white or all-Negro (A. 152); they have never

been located so as to promote desegregation and achieve

ment of a unitary school system (A. 476, 486, 508), although

the district has been aware since 1956 of the trend of popu

lation movement, including the tendency of whites to move

Rock realtor, even up to the time of the hearing in this case, who

would knowingly sell a lot in a “white” subdivision to a Negro

(A. 294). Newspaper advertisements reflecting listings of sale prop

erty by race were also introduced in evidence (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit

No, 3).

7 The thirteenth facility opened since 1956 was Metropolitan

High School, a vocational-technical school serving both Little Rock

and the Pulaski County Special School District. It is located out

side the district’s boundaries.

west and of Negroes to remain in the center or eastern

section of the city (A. 286-296, 637).8

8 Between 1956 and 1969 there were many instances of specific

actions taken by the district which developed or reinforced the

racial identifiability of its schools:

Bale and Williams Elementary schools were constructed prior

to 1961 in all-white neighborhoods and staffed with all-white facil

ities.

In 1961, the district decided to “convert” the previously all-white

Rightsell elementary school to an all-Negro school in order to

relieve overcrowding at nearby all-Negro elementary schools. No

consideration was given to the possibility of operating all schools

in the area on an integrated basis (A. 166-67; Safferstone V.

Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W. 2d 3 (1962)).

In 1963-64, while Henderson Junior High School was under con

struction, white pupils living in the far western section of the

city were transported by school district bus past West Side and

Dunbar Junior High Schools to attend the previously all-white

East Side Junior High (A. 171). No attempt was made to bus

these students to the nearest “neighborhood school” and/or to in

tegrate Dunbar. When construction of Booker Jr. High was com

pleted and East Side closed, however, only the Negro East Side

students were assigned to Booker; the white students went to West

Side (A. 478). Booker also drew students from overcrowded Dunbar

Jr. High (A. 496). Thus, the district did not make use of an op

portunity presented to it in 1964-65 to disestablish the identities

of West Side and Henderson as white junior high schools and

Booker and Dunbar as Negro junior high schools.

In 1963-64 the district opened Gillam Elementary School, located

in an all-Negro area, as a Negro school with an all-Negro faculty

(A. 473). Gillam was constructed nearly adjacent to the existing

Negro Granite Mountain Elementary School. Both schools are pres

ently operating under capacity, but when the district contemplated

construction of Gillam, no consideration was given either to ex

panding existing capacity at other elementary schools or to locating

a new facility so as to promote desegregation (A. 474).

In 1965 another primary school named for a Negro citizen was

opened with an all-Negro faculty— Ish Elementary School (A. 481-

82). At the same time, all-Negro Capital Hill Elementary School

was closed and its students assigned to other all-Negro schools, in

cluding Ish, rather than to nearby white elementary facilities (A.

482). Although the district was supposed to be operating under

freedom of choice at the time, see Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little

Rock, supra, 369 F.2d at 665, students assigned to Ish were not

afforded a choice of schools until the district was ordered to permit

9

The Oregon and Parsons Plans

In 1966, the school board contracted with a team from

the University of Oregon to prepare a long range plan of

desegregation for the district (A. 61-62). The findings of

that team were reported in early 1967 and became known

as the “ Oregon Report” (Defendants’ Exhibit No. 7). Ba-

ehoiee in Byrd v. Board of Directors of Little Bock School Dist.,

Civ. No. LR 65-C-142 (E.D. Ark. 1965).

When all-Negro Pfeifer and Carver schools became overcrowded,

the district did not offer Negro students a second choice of schools

(A. 315-16), but moved portable classrooms to the site to expand

the capacity of the schools and contain the Negro student popula

tion (A. 498-99). In contrast, Hall High School was declared over

crowded under the freedom-of-choice plan, necessitating the estab

lishment of an attendance zone. However, when the board drew

the zone it made no attempt to maximize desegregation in the

school (A. 222-23).

In addition to staffing new schools with all-white or all-Negro

faculties, the district hired teachers on a strictly racial basis

through 1964-65 (A. 28) ; thereafter, all attempts to achieve fac

ulty integration were on a purely voluntary basis only (A. 255).

And prior to July 1968, except for two white principals at Negro

schools, the district maintained a racial allocation of prineipalships,

with white principals at traditionally white schools and Negro

principals at “Negro” schools (A. 121-22).

In 1966, the district purchased a school site in Pleasant Valley,

an exclusively white upper-middle class subdivision (Defendants’

Exhibit No. 30; A. 213, 485), again without any consideration of

the racial composition of the neighborhood or the past history of

segregation (A. 486). Any school constructed on the site (there is

still a sign announcing that a school will be built on the site) would

be all-white; were Pleasant Valley, Walton Heights and Candle-

wood subdivisions not within the Little Rock district, the closest

school would be a predominantly Negro school in the Pankey area

(A. 488-89).

Finally,— and this list is by no means exhaustive of the means

by which this district maintained the segregated character of its

system—the school district undertook to build a new senior high

school (Parkview) in the far western section of the city in 1967

despite the availability of over four hundred vacant classroom

spaces at Horace Mann High School (A. 144-45). Three high

schools could still serve the high school population of the district

(A. 131) ; the overcrowding at the time was in junior high schools

(A. 617-18).

1 0

sically, the report recommended abandonment of the neigh

borhood school concept and restructuring of the district’s

schools through a capital building program combined with

pairing to create an educational park system (Ibid). The

cost of implementing the “ Oregon Report” in its entirety

was estimated to be some ten million dollars; howmver, as

the chief author and director of the study (Dr. Goldham-

mer) explained, much of this amount would have had to be

expended for building replacement and remodeling anyway

(A. 367). The Oregon Report would also have required a

transportation system for the school district (Ibid).

Following issuance of the Oregon Report, a school board

election was held in November 1967. Two incumbent mem

bers of the board who supported the recommendations of

the Oregon Report were replaced by candidates who cam

paigned against it (A. 416-18), and the vote was interpreted

as an indication (a) that the public would not support

implementation of the recommendations, and (b) that the

public would not vote bond monies or tax levies sufficient

to implement them.

The school board then directed the Superintendent and

his staff to prepare their own recommendations of a deseg

regation plan for Little Rock (A. 69). The Superintendent’s

proposals quickly became known as the “Parsons Plan”

(A. 70). The Parsons Plan proposed measures to deseg

regate Little Rock high schools and two groups of elemen

tary schools, but made no proposals for other elementary

schools or for junior highs. In March 1968, the board placed

a $5 million bond issue for implementing the Parsons Plan

on the ballot (A. 73-74). The millage increase for the bonds

was rejected (A. 75) and again, candidates favoring no

change in the status quo defeated incumbents who sup

ported the Superintendent’s plan (A. 180-81. See also, A.

417-21).

1 1

Development of the Plan Rejected by the

Court of Appeals

After the school district had responded to the Motion

for Further Relief, the district court set a hearing for

August 15, 1968 and suggested that the Board devise a

geographic zoning plan (A. 32a). The district did present

a geographic attendance zone plan at the August hearing

(A. 76). However, this plan was characterized as an “ in

terim” measure (A. 320) which required further study (A.

91) ; the district opposed making any change from freedom-

of-choice for 1968-69 and the hearing was limited to whether

or not a shift ought to be required for 1968-69. After the

second day of testimony, the hearing was recessed in order

to allow the district to develop and present a final plan

to completely disestablish the dual system effective with

the 1969-70 school year (A. 403-04). That plan was sub

mitted November 15, 1968 (A. 408d-408g).

Although cost was a major factor in the decision to

submit a zoning plan, no cost analysis of various alterna

tive approaches was ever requested or made (A. 513-14,

548-49).

The plan of the school board established mandatory at

tendance areas for all schools except the district-wide vo

cational-technical facility, Metropolitan High School. The

zones were approved as submitted except that the district

court required (A. 912-13) that the Hall High School zone

be redrawn in accordance with the October 10th proposal

of the Superintendent putting 80 Negro students in Hall

High School (which had been rejected by the Board).

The results under the two zoning plans and the past

enrollments at Little Rock schools are shown in the follow

ing table:

TABLE 1

(Pupil (Limited

Segregation) ' Placement) Free Choice) (Free Choice) (Aaron)

1956

Enrol-

1960-61

Enrol-

196U-65

Enrol-

1968-69

Enrol-

Zones

1956

(Clark I )

Zones

1965

(Clark II)

Zones

8/68

Zones

11/68

Faculty

Assignments

School j w ..... M l ■■■" w w N W N W N ~ y N w N w

f

N

f

HIGH SCHOOLS

White:

Central 21*75 1686 7 2206 76 151*2 512 2107 337^ 2005 210 121*9 61*1* 11*1*7 1*81 85 15

Hall ' . . . . . . 881* 5 15U0 18 11*36 l* 835 0 11*58 60 11*08 3 1361 U 81* 16

Parkview — — — — — — 519 1*6 — — — — 863 56 729 52 81* 16

Negro:

Mann 0 582 0 821 0 1239 0 801 363 1*13 359 1065 233 912 66 978 71 29 ^

JR. HIGH SCHOOIs

White:

East Side 852 0 606 0 — — — — 355 255 — — — — — - — —

West Side 1268 0 1006 0 91*7 36 657 318 807 283 252 738 1*71 398 1*95 395 80 20

Pulaski Heights 1*83 0 880 0 800 12 613 36 61*1* 1*0 779 39 672 65 61*9 56 78 22

Forest Heights 678 0 851* 0 975 1* 101*0 8 760' 0 937 1 908 0 i 901* U 81. 19

Henderson — —- — — 1*52 1* 822 16 — — 683 66 808 2 | 813 0 79 21

Southwest 938 0 991* 2 987 27 866 5U 966 1*2 859 62 911* 1*1 80 20

TABLE 1 (continued) P- 2

{Segregation)

1956

Enrol

lment

(Pupil

' Placement)

1960-61

Enrol

lment

(Limited

Free Choice)

1961**65

Enrol

lment

(Free Choice)

1968-69

Enrol

lment

(Aaron)

Zones

1956

Plan

(Clark I>

Zones

1965

Plan

(Clark II)

Zones

8/68

Plan

Zones

11/68

Plan

Faculty

Assignments

11/68 Plan

School E 1 W N W N W N W N W N W N W N w N

JR. HIGH SCHOOljS % %

Negro;

Dunbar o 1053 0 11*07 0 95 2 0 685 283 717 289 661* 79 800 27 71*1 57 1*3

Booker — — 0 669” 0 756 0 703 .................. 252 738 136 705 89 71*7 56 1*1*

ELEMENTARY SCH( OLS

White;

Bale 1*1*2 •■o 508 0 501 3 31*9 0 1*61 11 1*61 11 67 33

Brady U85 p 669 o • 669 1 657 0 665 0 665 0 68 32

Centennial 283 0 30 6 10 138 202 217 29 129 11*9 109 231 57 1*3

Fair Park 35U 0 266 0 253 0 208 0 227 0 227 0 67 33

Forest Park 532 0 5hh 0 383 2 1*51 0 370 1 370 1 71 29

Franklin 706 0 61*9 0 511 11 607 56 526 61 526 61 72 28

Garland 1*37 0 371 0 283 15 263 1 213 7 260 62 71 28

Jackson 21*6 0 278 3 — — 250 89 — — — — — —

Jefferson 672 0 612 0 513 0 623 0 531* 0 531* 0 71 29

Kramer 3U7 0 283 0 91 76 139 63 118 95 78 70 63 37

■ Lee 1*33 0 376 2 210 155 267 11* 218 70 219 70 62 38

TABLE 1 ( continued) P- 3

{Segregation)

1956

Enrol

lment

(Pupil

' Placement)

1960-60.

Enrol

lment

(Limited

Free Choice)

196U-65

Enrol

lment

|JVee Choice)

1968-69

Enrol

lment

(Aaron)

Zones

1956

Plan

(Clark I>

Zones

1965

Plan

(Clark II)

Zones Zones

8/68 11/63

Plan Plan

Faculty

Assignment

11/68 Plan

School w to ------w N \ T N t r IT TT 53 N W N w N w N

%

ELEMENTARY SCHCOLS

White?

McDemott — — — — 1*1*8 1 — — — Ull* 0 1*12 0 69 31

Meadowcliff. 1*2? 0*- 1*99 0 579 0 , 1*85 0 553 0 553 0 73 27

Mitchell 379 0 355 27 1*1 331* 276 25 102 292 97 290 . 67 33

Qakhurst 1*73 0 396 2 281 53 360 31 330 21* 330 21* 69 31

Parham 1*38 0 1*07 0 270 81 209 130 187 151* 199 161 71 29

Pulaski Height? 569 0 500 0 1*1*6 5 1*50 7 333 0 333 0 69

Romine 336 0 1*81 7 316 97 1*35 86 380 100 380 100 72 2S

Terry — — 267 0 1*90 0 21*2 0 1*1*2 0 1*1*2 0 72 ae

Western Hills — — 178

Tf/

12““ 206 6 — — 201* 0 201* 0 67 33

Williams 1*23 0 615 0 71*5 6 592 2 616 3 616 3 67 33

Wilson 81*3 0 551 10 1*11 77 521 11 1*37 1*6 1*37 1*6 70 30

Woodruff 329 0 328 2 212 62 235 0 216 18 232 1*6 70 30

Negro:

Bush 0 196 0 199 0 113 — — — — — — — —

Capital Hill 0 1*57 0 237 — ™— — — “““ ****

TABLE 1 (continued) p . 1*

(Pupil (Limited

(Segregation) ' Placement) Free Choice) (Free Choice)

1956

Enrol

lment

1960-61

Enrol

lment

196U-65

Enrol

lment

1968-69

Enrol

lment -

School W N"~ ■W N W N W N

ELEMENTAL SCH( OLS

Negro:

Carver 0 785 0 901* 0 81*2

Gibbs 0 839 0 1*97 0 390

Gillam 0

2

188”1 0 185 0 213

Ish — — 0 587^ 0 589

Granite Mounta: n 0 557 0 1*76 0 U66

Pfeifer 0 136 0 178 0 190

Rightsell 0 373 0 901 0 390

Stephens 0 1*86 0 582 0 369

Washington 0 538 0 580 0 506

Including Te hnical High S :hool students Initial Enrollment

Initial Enro! .lment 1966-67 % $ / Carver- Pfeifer

(Aaron) (Clark I ) (Clark II)

Zones Zones Zones Zones Faculty

1956 1965 8/68 11/68 Assignments

Flan Plan _________ Plan__________Plan________ 11/68 Plan

N W N w N w N W N

% %

281*

%

731 16 79U 16 791* 56 1*1*

70 289 20 317 1*8 389 56 1*1*

— 18 11*1 18 lltl 56 1*1*

391 355 13 606 8 1*81* 56 u i*

12 61U 0 1*71 0 1*71 59 1*1

281* 731 11* 11*1 11* 11*1 57 1*3

109 329 51 39U 5U 390 56 1*1*

11*5 369 83 365 31* 313 57 1*3

1*1* 1*99 10 505 7 1*83 58 1*2

’/ Initial EnrcIlment 1961-6 >

y Initial Enrcllment 1965-6

16

Fewer Negro students would attend predominantly white

schools under the zoning plan than had been enrolled in

such schools under freedom of choice (A. 534-35); there

would he “very little” integration under the zoning plan

(A. 162) since the zones were drawn in a manner that al

lowed schools to remain all-white and all-Negro (see A.

434).

Most of the witnesses at the hearing agreed that the

Parsons Plan was a better integration plan, albeit incom

plete, than the board’s zoning proposal (A. 129 [superin

tendent Parsons], 194 [Board President Barron], 298-99

[Board member Meeks], 678 [Dr. Dodson], 819 [Dr. Gold-

hammer, principal author of the Oregon Report]). The

Superintendent also testified that various zones drawn in

the board’s plan, such as those for Gillam Elementary and

Hall High Schools, did not further the goal of integration

(A. 158). From his study of the board’s proposals, Dr.

Goldhammer concluded that they did not provide for a

unitary school system, and would not be an improvement

over free choice (A. 381-82).

Alternatives Available to the District

Plaintiffs’ expert witness Dr. Dodson said that the zones

froze in the segregated character which the schools had

developed in the past (A. 686). He recommended imple

mentation of a plan not based on the neighborhood school

concept (A. 673-74). He traced the origin of the concept

to the “common school” notion at the base of public educa

tion (A. 658-59) but said that the neighborhood school had

become “ a place where people who are more privileged try

to hide . . . and it’s been made sacred in recent thinking

about in proportion as Negroes get close to it. It has be

come an exclusive device, that is the opposite of the com

17

munity school” (A. 659). Dr. Dodson pointed out that in

a city with racially segregated housing patterns, effective

desegregation could not be accomplished if the neighbor

hood school concept were adhered to (A. 673-74). Only by

eliminating the racial identities of the schools and allowing

them to take on new identities as common schools could an

integrated unitary system be achieved (A. 681-82). He dis

cussed alternative approaches used in other districts (A.

674-76). He was of the opinion that if Little Rock’s high

schools were to be zoned to desegregate them, the zones

should have been drawn from east to west as in the Parsons

Plan (A. 678).

Dr. Gfoldhammer testified that the initial study of the

Little Rock School District by the team which drafted the

Oregon Report demonstrated that the district’s progress in

eliminating the dual system was much slower than could

have been expected; that considering the rapid growth in

enrollment in the school system, free choice would never

have worked (A. 357-59).9 Whereas the board’s plan pro

posed to zone all schools, the University of Oregon team

had concluded that in a residentially segregated commu

nity such as Little Rock, no single approach would do the

entire job of conversion to a unitary system (A. 365). The

Oregon team’s recommendations therefore incorporated

several different features: a capital construction program

to develop educational parks and larger attendance cen

ters, pairing some schools and a busing system of student

transportation (A. 365-67). Although the report carried

a cost estimate of $10 million, this price included consider

able replacement or modernization of facilities which would

have had to be carried out irrespective of any desegrega

9 Superintendent Parsons stated that he had never expected

white students to choose identifiably Negro schools under freedom

of choice (A. 330-31).

18

tion plan (A. 367). The cost of coming as close to the

Report as possible without abandoning or remodeling build

ings would require less than $500 thousand, for busing,

inservice training and compensatory education programs

(A. 368-69).

Dr. Goldhammer said that the Parsons Plan, the Oregon

Report and the “Walker”10 plan were each better means

of desegregating the schools than the board’s zoning pro

posals (A. 399, 819). (He estimated that the “Walker”

plan would be the least expensive to implement, A. 821).

The Board President, also, was of the opinion that these

plans would result in more integration in the Little Rock

public schools than would be accomplished under the zoning

plan. They would thus eliminate the racial identifiability

of the schools, something which the zoning plan would fail

to achieve (A. 762. See also, A. 298, 636).

The district rejected these alternatives because they each

required expenditure of funds which Little Rock voters

had demonstrated, by their votes on the bond issues, that

they would not provide (A. 334, 337-40, 415-23, 428, 456,

653-54). The Superintendent said, in fact, that the com

munity had “turned down every educationally desirable

plan and now we are left with only zoning as a feasible

plan” (A. 556-557). Some funds were available to the dis

trict, however, including State monies for a transportation

system (A. 341-43, 641-46) and Dr. Goldhammer suggested

that funds might have to be diverted in order to accom

plish unification of the system (A. 821).

The District Court approved the Board’s zoning plan.

The Court of Appeals held that action was error.

10 A plan developed by a group of Negro citizens and organiza

tions which combined grade restructuring, pairing and transporta

tion with recommendations for future development of larger, more

centralized attendance centers.

19

ARGUMENT

As we read the Petition, the Little Rock School Board

urges review of the decision below on two major grounds:

that the Eighth Circuit has required Little Rock to abandon

the “neighborhood school” method of assignment, and that

the Courts of Appeals are divided in their interpretations

of this Court’s school desegregation decisions.

Petitioners assert (p. 11) that

[t]he effect of the majority opinion below is to deny

to the Little Rock School District the right to assign

its public school students as they are assigned, and

have been for decades, by the vast majority of the

nation’s school districts.

The fact is that “neighborhood schools” have been paid lip

service only, and not much more, not only in Little Rock

but throughout most of the country. See Weinberg, Race

and Place—A Legal History of the Neighborhood School

(U.S. Gov’t Printing Office, Catalogue No. FS 5.238:38005,

1967). When “neighborhood schools” would have meant

integrated schools, this school system was unwilling to draw

geographic attendance zones.

Petitioners correctly state that when this litigation was

begun plaintiffs suggested the remedy of attendance zoning.

That remedy would have meant desegregation so the school

district opposed it while it built white schools in western

Little Rock. However, to say, as petitioners do (p. 7), that

when zoning was adopted in 1969 “plaintiffs achieved the

basic relief they had earlier sought in the suit” is to con

fuse form with substance. Surely the majority of the Court

of Appeals was correct in not assigning any magic value to

“neighborhood schools” but investigating whether there

would be integrated schools.

2 0

No other Court of Appeals would have approved the

Little Rock plan.11 In an opinion remarkably similar to

that below, for example, the Tenth Circuit has recently

held:

The attendance zones as originally formulated were

superimposed upon racially defined neighborhoods and

were, therefore, discriminatory from their inception

[citing Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 397

F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1967)]. . . . Similarly, the pattern

of new school construction has preserved, rather than

disestablished, the racial homogeny of the Tulsa at

tendance zones.

As conceived and as historically and currently admin

istered, the Tulsa neighborhood school policy has con

stituted a system of state-imposed and state-preserved

segregation, a continuing legacy of subtle yet effective

discrimination.

United States v. Board of Educ., Independent School Dist.

No. 1, Tulsa, No. 338-69 (10th Cir., July 28, 1970).

11 Virtually every district court opinion which petitioners claim

(Petition, pp. 13-14) evidences confusion about the meaning of this

Court’s decisions has been reversed, and appropriate guidelines

given by the Courts of Appeals. Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ.

and Thomie v. Houston County Bd. of Educ., No. 29,121 (5th Cir.,

February 5, 1970) ; Hilson v. Ouzts, No. 28491 (5th Cir., April 3’

1970) ; United States v. State of Georgia, No. 29067 (5th Cir.,

June 18, 1970) (permitting intervenors to contest adequacy of

desegregation formulas and suggesting their facial invalidity) ;

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, No. 14,544 (4th Cir., June

22, 1970), cert, denied, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522 (June 29, 1970). The

Northcross decision cited by petitioners was reversed by this Court,

397 U.S. 232 (1970). In Graves v. Board of Educ. of North Little

Rock, where the parties are represented by the same counsel as in

this litigation, it was agreed that plaintiffs’ appeal be dismissed on

the condition that further proceedings in the district court would

be governed by the outcome of the Little Rock appeal.

2 1

The Fourth Circuit since 1968 has consistently held that

“neighborhood schools” cannot abort the constitutional im

perative. Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, supra;

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 14,517

(4th Cir., May 26, 1970), cert, granted on other issues, 38

U.S.L.W. 3522 (June 29, 1970).12

The Fifth Circuit has approved plans which it views as

preserving “neighborhood schools” only where such plans

establish unitary school systems; no plan has been approved

which results in as little actual desegregation as Little

Rock’s. E.g., Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, 423 F.2d 203, 208, n. 7 (5th Cir. 1970) (“Under

the facts of this case, it happens that the school board’s

choice of a neighborhood assignment system is adequate to

convert the Orange County school system from a dual to a

unitary system” ) ; Andrews v. City of Monroe, No. 29358

(5th Cir., April 23, 1970) (typewritten slip opinion at p. 4:

“However, we do not reject the School Board’s plan solely

on the ground that it does not fit the Orange County defini

tion of a ‘neighborhood’ system. Even if, as presently

constituted, the plan were a true neighborhood plan, we

would reject it because it fails to establish a unitary sys

12 “ The District Court should not tolerate any new scheme or

‘principle,’ however characterized, that is erected upon and has the

effect of preserving the dual system. This applies to the ‘neighbor

hood school’ concept, a shibboleth decisively rejected by this court

in Swann (Judge Bryan dissenting), as an impediment to the per

formance of the duty to desegregate. The purely contiguous zoning

plan advanced by the Board in that case was rejected by five of

the six judges who participated. A new plan for Norfolk that is

no more than an overlay of existing residential patterns likewise

will not suffice.” Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, No.

14,544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970) (concurring opinion of Sobeloff

and Winter, JJ., pp. 1-2), cert, denied, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522 (June 29,

1970).

2 2

tem.” ) ; Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills

borough County, No. 28643 (5tli Cir., May 11, 1970).13

Finally, the Sixth Circuit has recently rejected the argu

ment that zoning is per se constitutional.

The District Court, in examining the record before it,

has apparently determined that revision of the atten

dance zones is necessary to insure the Board’s compli

ance with its affirmative duty to disestablish segrega

tion with a plan which “promises realistically to work

now.” There is nothing in the record, including the

failure of the prior reviewing courts to disturb the zon

ing, which would justify disturbing the District Court’s

determination. Nor does the absence of a finding that

the present zones were racially gerrymandered or that

the Board acted in bad faith preclude the District Court

from ordering this remedial relief. Green v. County

School Board, supra, at 439; JacJcson v. Marvell School

District No. 22, 416 F.2d 380, 385 (8th Cir. 1969);

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682, 684 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S.

940 (1969).

The Board’s assertion that the District Court’s order

requiring revision of the zones was designed to achieve

a predetermined racial balance [footnote omitted] in

13 In noting our view, based on our reading of the decisions, that

none of the Courts of Appeals would have affirmed the district

court’s acceptance of the Little Rock zoning plan, we do not mean

to suggest agreement with the Fourth Circuit’s limitation of remedy

by its “reasonableness” doctrine, see Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., No. 281, O.T. 1970,

cert, granted, June 29, 1970, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522, or with the Fifth

Circuit’s use of the “neighborhood school” doctrine to justify a

lesser number of segregated schools in a district than Little Rock’s

plan would have produced, see Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s of Mobile, No. 436, O.T. 1970.

23

the schools in violation of section 407(a)(2) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6) is also

without merit. . . .

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson, No. 19720 (6th

Cir., June 19, 1970) (slip opinion at pp. 5-6). See also,

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Educ. of Nashville,

Civ. No. 2094 (M.D. Tenn., July 16, 1970).

This matter is best put in its proper perspective by ex

amining what the Court of Appeals did, and not what peti

tioners say it did! Little Rock’s plan was not rejected

because “ several” (Petition, p. 8) schools remained racially

identifiable. Compare Appendix to Petition, pp. A-15 to

A-16, pp. 13-15 supra. It was rejected because it effected

at most a de minimus change in the patterns of racially

segregated school attendance which characterized the dual

system in Little Rock. All that has been decided is that

“desegregation” plans which don’t work are not constitu

tional; racial balance has been neither required nor pro

hibited. The arguments of Petitioners are thus much like

those made three years ago by school boards when the Fifth

Circuit indicated that free choice plans would not be in

definitely approved if they failed to produce integration.

Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 940

(1967).

The decision below is completely in accord with the spirit

of Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), where in the context of free choice this

Court refused to view any particular method of desegrega

tion as sacrosanct, emphasizing instead the result. The

Court of Appeals properly concluded that “geographic

attendance zones . . . must be tested by this same standard.”

(Appendix to Petition, p. A-14). Petitioners attempt to

circumvent application of so pragmatic a test to their zon-

24

mg plan by interpreting Brown v. Board of Educ. to have

sanctioned attendance zoning for all time.

This Court in Brown recognized geographic districting

as the normal method of pupil placement and did not

foresee changing it as the result of relief to be granted

in that case. . . . the original command of Broivn that

public school systems must operate free from racial

classifications has not been altered by this Court’s sub

sequent decisions in the matter. This was confirmed

as recently as Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), in which this Court said

it was the constitutional duty of every school district

to operate “ school systems within which no person is

to be effectively excluded from any school because of

race or color.”

(Petition, pp. 11, 16). Even if this Court in Brown had

viewed zoning as a sufficient remedy in the cases before it14

(perhaps in all cases) and had not foreseen changing it,

we think it is also fair to say that this Court anticipated

compliance with its decision rather than the fourteen years

of evasion and continued discriminatory practices which

mark this case. “Defendants contend that they have ex

cluded no one from any school, but they are still effectively

operating dual schools.” Christian v. Board of Educ. of

Strong, Civ. No. ED-68-C-5 (W.D. Ark., Dec. 15, 1969).

One final argument of the Petitioners deserves note. They

seek to characterize a school district’s choice of the zoning

attendance assignment method as an innocent choice, which

may produce racially identifiable schools only “ [bjecause

of the tendency of the people in this country, north, south,

east or west, to reside in those areas of a city populated

14 As noted above, geographic zoning in Little Eock in 1956

would have meant desegregation. See p. 19 supra.

25

by other citizens of their race” . . This pernicious argu

ment is, first, totally unsupported by any evidence in this

record. In fact, this record contains uncontradicted evi

dence to the contrary concerning racial discrimination

which is pervasive in Little Rock (A. 294, 743-44, Plaintiffs’

Exhibit No. 3; cf. A. 289-91, 746). Second, petitioners’ bald

assertion is rebutted by innumerable studies by govern

mental bodies., Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A

Report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 201-02, 254,

Legal Appendix at 255-56, and private authors, e.g.,

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors 233 (1955); Weaver, The

Negro Ghetto 71-73 (1948). Third, it is disproved by re

cent affirmative action of the Congress, Fair Housing Act

of 1968, 42 U.S.C.A. §§3601 et seq. (Supp. 1970). Finally,

it ignores the very real complicity, through site selection,

staffing, etc., of the school district in the existing pattern

of racially identifiable schools. See the opinion below,

Appendix to Petition, pp. A-15 to A-16, nn. 19-22 and ac

companying text. “ The question is no longer where the

first move must be made in order to accomplish equality

within our society; the question has become and possibly

always has been who has the power and duty to make those

moves so as to advance the accomplishment of that equal

ity.” Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.

734, 742 (E.D. Mich. 1970).

This case is an inappropriate one for review, then, be

cause (1) there is no difference of opinion between the

various Courts of Appeals on the constitutionality of a

zoning plan which produces as little real desegregation as

Little Rock’s; (2) the opinion below neither forbids “neigh

borhood schools” nor mandates “ racial balance” in the pub

lic schools—it is the rejection of a specific plan evaluated

in the context of the specific factual circumstances of this

district; (3) the Court was clearly correct in insisting that

26

desegregation plans achieve desegregation in order to win

judicial approval. This school district’s distortion of Brown

v. Board of Educ., supra, is deserving of no less rapid dis

patch by this Court than the similarly twisted interpreta

tion of that decision offered by the Norfolk School Board.

(Review of the Fourth Circuit’s rejection of their theory

was denied by this Court one week after the Court of Ap

peals’ decision). At best, this case is one for summary

affirmance.

CONCLUSION

W h e r e f o r e , Respondents respectfully pray in light of

the foregoing that the writ be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n W . W a l k e r

W a l k e r , R o t e n b e r r y , K a p l a n ,

L a v e y a n d H o l l in g s w o r t h

1820 West Thirteenth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

J a c k G reenberg

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

APPENDIX

LITTLE P.OCK SCHOOL DISTRICT

FACULTY DESEGREGATION

1969-70

The L it t le Rock P ublic Schools w i l l assign and reassign teachers fo r the

1969-70 sch ool year to achieve Che fo llow in g :

1. The number o f Negro teachers w ithin each sch oo l o f the d i s t r i c t w i l l

range from a minimum o f 15% to a maximum o f 45%.

2. The number o f white teachers w ith in each sch oo l o f the d i s t r i c t w i l l

range from a nininun o f 55% to a maximum o f 85%.

A p p lica tion o f the above regu la tion s to incumbent personnel would

re su lt in the fo llo w in g fa cu lty assignments fo r 1969-70. However, lo s s o f

incumbent personnel through normal a t t r i t io n and resign ation s due to these

proposed reassignm ents, and the re su ltin g n e cess ity to employ replacement

personnel, make i t im possib le to cake a p re c ise estim ate o f the fa cu lty

assignments by race fo r 1969-70 at th is time.

School N

1968-69

teachers

. W T N

1969

teach

T.J.

-70

T

Negro

No. %

White

No.

4*

•7

or -

teach

N

in

ers

W

Sr. High

Central 5 93 98 14 78 92 14 15 78 85 + 9 -15

H all 1 68 69 10 54 64 10 16 54 84 + 9 -14

Mann 36 5 41 14 34 48 14 29 34 71 -2 2 +29

M etropolitan 2 39 41 7 34 41 7 17 34 83 + 5 - 5

Parkview 7 24 31 6 31 37 6 16 31 84 - 1 4- 7

T ota l Sr. H. 51 229 280 51 231 282 51 231

J r. High

Booker 31 4 35 17 22 39 17 44 22 56 -14 +18

Dunbar 30 4 34 16 21 37 16 43 21 57 -14 +17

For. H ts. 1 44 45 8 34 42 8 19 34 81 + 7 -1 0

Henderson 4 36 40 8 31 39 8 21 31 79 4- 4 - 5

Pul. Hts. 1 30 31 7 25 32 7 22 25 78 4* 6 - 5

Southwest 1 44 45 9 25 44 9 20 35 80 4- 8 - 9

West Side 5 39 44 8 33 41 8 20 33 80 + 3 - 6

73 201 274T ota l Jr. H. 73 201 274 73 201

1968-69

teachers

1969-70

teachers Negro White

+ or - in

teachers

School N W T N W T No. % No. % N W

Elementary O

Bale 2 16 18 6 12 18 6 33 12

1 :

67 + 4 - 4

Brady 2 22 24 8 17 25 8 32 17 68 + 6 - 5

Bush 5 1 6

Carver 29 4 33 16 20 36 16 44 20 56 -13 +16

Centennial 4 9 13 6 8 14 6 43 8 57 + 2 - 1

Fair Park 1 9 10 3 6 9 3 33 6 67 + 2 - 3

For. Park 2 13 15 4 10 14 4 29 10 71 + 2 - 3

Franklin 2 20 22 7 18 25 7 28 ' 18 72 + 5 - 2

Garland 1 12 13 4 10 14 4 28 10 71 + 3 - 2

Gibbs 16 0 16 8 10 18 8 44 10 56 - 8 +10

Gillam 7 2 9 4 5 9 4 44 5 56 - 3 + 3

Gr. Mtn. 13 3 16 7 10 17 7 41 10 59 - 6 + 7

Ish 15 5 20 8 10 18 8 44 10 56 - 7 + 5

J e ffe rso n 2 18 20 6 15 21 6 29 15 71 + 4 - 3

Kramer 2 6 8 3 5 8 3 37 5 63 + 1 - 1

Lee 3 11 14 5 8 13 5 38 8 62 + 2 ~ - 3

McDermott 3 14 17 5 11 16 5 31 11 69 + 2 - 3

M eadowcliff 2 20 22 6 16 22 6 27 16 73 + 4 - 4

M itch e ll 3 11 14 5 10 15 5 33 10 67 + 2 - 1

Oakhurs t 2 10 12 4 9 13 4 31 9 69 + 2 - 1

Parham 3 10 13 4 10 14 4 29 10 71 + 1 0

P fe ife r 7 1 8 3 4 7 3 43 4 57 - 4 + 3

Pul.. Hts 1 17 18 4 9 13 4 31 9 69 + 3 - 8

R ig h tse ll 13 4 17 8 10 18 8 44 10 56 - 5 + 6

1968-69 1969-70 + or - in

teachers teachers Negro White teachers

School N W T N W T No. % No. % N w

Romine 2 14 16 5 . 13 18 5 28 13 72 + 3 - 1

Stephens 12 2 14 6 8 14 6 43 1 8 57 - 6 + 6

Terry 1 18 19 5 13 18 5 28 13 72 + 4 - 5

Washington 16 3 19 8 11 19 8 42 11 58 - 8 + 8

Western R i l l s 1 8 9 3 6 9 3 33 6 67 + 2 - 2

W illiams 2 23 25 7 17 24 7 29 17 71 + 5 - 6

Wilson 2 17 19 6 14 20 6 30 14 70 + 4 - 3

Woodruff 1 9 10 3 7 10 3 30 7 70 + 2 - 2

T ota l Elem. 177 332 509 177 332 509 177 332

I f a l l teachers in the L it t le Rock :School System returned fo r the 1969-70

sch oo l year, the fo llo w in g numbers o f Negro and white teachers would be

tran sferred from th e ir 1968-69 sch oo l o f assignment.

Negro White

Senior High 23 34

Junior High 28 35

Elementary 60 63

Total 111 132

Grand T ota l 243

la

Defendants’ Exhibit 24

2a

Defendants’ Exhibit 25

(See Opposite) SKr”

STUDENT DESEGREGATION’ 1969-70 Q

Tlic Little Rock School District will he divided into geographic attendance zones

for elementary, junioi high, and senior high schools as indicated on the accompanying map.

The distribution of students according to race will be approximately that indicated in

* Tables I, II, and III.

TABLE I

si:',toe high

accoufartn

school ait:::

Hi 1903-69:

SCHOOL PROJECTIOliS IT)?. 1909-79 ! ’SING ZONES

MAP WITH 11th AND 17th SPADE STUDENTS COL

ITT 111 1908-09 ALP TIE RACIAL CBURDSITION

AS SHOT! O:J THE

TINUING i;i THE

OE EACH SCHOOL

High School

1968-6 9 Enrollment 1969--70 P ro je ction s

N Vi Total I T W T ota l

Central 517 1,542 2,054 481 1,447 1,920

Hall U 1,436 1,440 4 1,361 1,365

' lan.n 801 0 801 978 66 1,044

Parkview i*G 519 565 52 729 781

-Parkview co n s is te d o f grader, 8 , 9 , and 10 in 1908-G9.

I t w i l l serve grades 9 , 10, and 11 in 19G9-70,

TABLE II

JUNIOR HIGH

ACCOUNT ATT

SCHOOL ATiT?

IN 19G8-G9:

SCHOOL PROJECTIONS FOR 1969-70 USING ZONES AS SHOWN ON THE

j TAP WITH 1969-70 NINTH GRADE STUDENTS CONTINUING IN TIE

•TEI) IN 19G3-69 AND THE RACIAL COMPOSITION OF EACH SCHOOL

Jun ior High School

1960-69

N

Enrollment ------g ---------- T ota l

1969-70

IT-------

Prognotions

W Total

Booker 703 0 703 747 . 89 836

Dunbar 685 0 605 741 21 768

Forest Heights 8 1,040 1 ,043 4 904 908

I ler.dcrson 16 822 838 0 813 813

Pulaski Heights 36 613 649 56 649 705

Southwest 27 987 1 ,014 41 914 955

West: Side 657 • 318 975 495 395 890

tab u : h i

ELITIENTARY SCHOOL PROJECTIONS FOR 19G9-70 !JS I NS ZONES AS SHOWN Oil THE

ACCOMPANYING MAP KID THE RACIAL COMPOSITION OF EACH SCHOOL IN 1968-69

Elenentary

Capacity -

28 x No. o f

1968--69 EmxxLlnent 1969--70 P ro jection s

School Classrooms N W T ota l N W T otal

Bale 532 3 501 504 11 461 472

Brady 644 . 1 669 670 0 665 665

Carver 840 822 0 822 794 ’ 16 810

Centennial 336' 202 138 340 231 109 340

F air Park 308 0 253 253 0 227 227

Forest Park 532 2 383 385 1 370 371

Franklin 700 11 511 522 .61 526 587

Garland 392 15 283 298 62 260 322

Gibbs 504 390 0 390 389 48 437

Giiiain 364 213 0 213 141 18 159

Granite Mount. 504 466 0 466 471 0 471

Ish 504 589 0 589 484 8 492

J e ffe rso n 672 0 513 513 0 534 534

Kramer 308 76 91 167 70 78 148

Lee 448 155 210 365 70 219 289

McDermott 364 1 448 449 0 412 412

.Ueadcwcliff 672 0 579 579 0 553 553

M itch e ll 364 334 41 375 290 97 387

Oakhurst 392 53 281 334 24 330 354

Parham 364 81 270 351 161 199 360

P fe ife r 112 190 0 190 141 14 155

Pulaski Hgts. 448 5 446 451 0 333 333

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS, Continued, pape 2

Capacity - 1968-69 Enrollment 1969-70 P ro je ction s

Elementary

School

28 x No. o f

Classrooms N W

R ip h tso ll 448 390 0

Rornine 504 97 316

Stephens 560 369 0

Terry 532 0 490

VJashington 560 506 0

Western H ills 280 6 206

VJilliams 700 6 745

VJilson 504 77 411

Woodruff 336 62 212

T otal N W T otal

390 390 54 444

413 100 380 ■ 480

369 313 34 347

490 0 442 442

506 483 7 490

212 0 204 204

751 3 616 619

488 46 437 483

274 46 232 273

3a

4a

Defendants’ Exhibit 8

(See Opposite) SST’

L IT T L E ROCK PU BLIC SCHOOLS

If non-overlapping attendance d istricts were created at all levels

(elem entary, junior high school, and senior high school), the pattern

of enrollm ent by races would c lose ly approxim ate the follow ing:

Senior High School Efficiency

Capacity

White Negro Total

Central High School 2, 400 2, 005 210 2, 215

Hall High School 1 ,4 0 0 1 ,4 5 8 60 1, 518

Mann High School 1 ,4 0 0 359 1 ,0 6 5 1 ,4 2 4

Totals 5, 200 3, 822 1 ,3 3 5 5, 157

Junior High School

E fficiency

Capacity White Negro Total

Booker 900 252 738 990

Dunbar 1 ,0 0 0 289 664 953

F o rest Heights 1 ,0 0 0 937 1 938

Henderson 750 683 66 749

Pulaski Heights 750 779 39 818

Southwest 1 ,0 0 0 966 42 1 ,0 0 8

West Side 900 538 316 854

Total 6, 300 4,4G 9 1 ,8 6 6 6, 355

E L E M E N T A R Y S C H O O L S

E ffic ie n cy

School Capacity White Negro Total

Bale 532 349 0 349

Brady 672 657 0 657

C a rv er-P fe ifer 1003 284 731 1015

Centennial 336 217 29 246

Fair Park 336 208 0 208

Forest Park 560 451 0 451

Franklin 728 607 56 663

Garland 532 263 1 264

Gibbs 784 70 289 359

Granite Mt, 896 12 614 626

Jackson 308 250 89 339

Jefferson 700 623 0 623

Kramer 336 139 63 202

Lee 504 267 14 281

M eadow cliff 504 485 0 485

M itch ell 420 276 25 301

Oakhurst 448 360 31 391

Parham 392 209 130 339

Pulaski Heights 588 450 7 457

R ig h tse ll 448 109 329 438

Romine 532 435 86 521

Stephens 560 145 369 514

Washington 560 44 499 543

Williams 532 592 2 594

Wilson 532 521 11 532

Woodruff 336 235 0 235

30th § Pulaski 504 391 355 746

Terry 364 242 ___ 0 242

Total 14952 8891 3730 12621

GRAND TOTAL 26452 17202 6931 24133

5a

6a

Defendants’ Exhibits F and G

(See Opposite) H r1

EXH IBIT F

Residence Location of White and Negro Senior High

School Students by School Attendance Areas and

G radcs— November 1955

Central, and T echnical H igh S chool

10th 11th 12th Total'

T otal W h i t e ................. 902 821 752 2475'

H orace M anx H igh S chool

T otal N egro .................. 248 204

T otal W hite aNii N egro

EXH IBIT G

School District Enumeration— May, 195G

Little Rock Public Schools

Senior High School Attendance Areas

Grades 10-12 Inclusive

%

White Colored Total Colored

Horace Mann High School 3(53 413 77G 53.2%

Central High School and

Tech High School ........ 2107 007 * >« > ( 2444 13.6%

West End High School

(Est. 1957) .................... 835 0 835 0 .0 %

Grand T o t a l ............ 4055

130 582'

3057'

7a

8a

Exhibit H

(See Opposite) Kir’

EXH IBIT It

Forecast of Junior High School Pupils Entitled to Free

Public Education by Junior High School Attendance Areas

for the School Year 1957-58 Based Upon the Enumeration

Completed May, 1956

% of % of Total

No. School Jr. Hi. Age

Pupils Membership Enumeration

East Side White 355 58.2

Kcgro 255 41.8

Total 610 100.0 12.14

West Side White 807 74.1

Negro 283 25.9

Total 1090 100.0 21.30'

Pulaski Heights White 644 92.7

Negro 40 7.3

Total 684 100.0 13.56'

Forest Heights White 760 100.0

Negro 0 0.0

Total 760 100.0 15.10'

Southwest White 866 94.4

Negro 54 5.6

Total 920 100.0 18.20

Dunbar White 283 28.3

Negro 717 71.7

Total 1000 100.0 19.70

Grand T otal . . 5084 100.00

9a

M E 1 L E N P R E S S I N C . — N . Y . C . 2 1 9