Jenkins v. Missouri Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 16, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Missouri Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellants, 1985. f774aacb-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/754e37ac-2059-44ed-8770-69d46beba8aa/jenkins-v-missouri-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

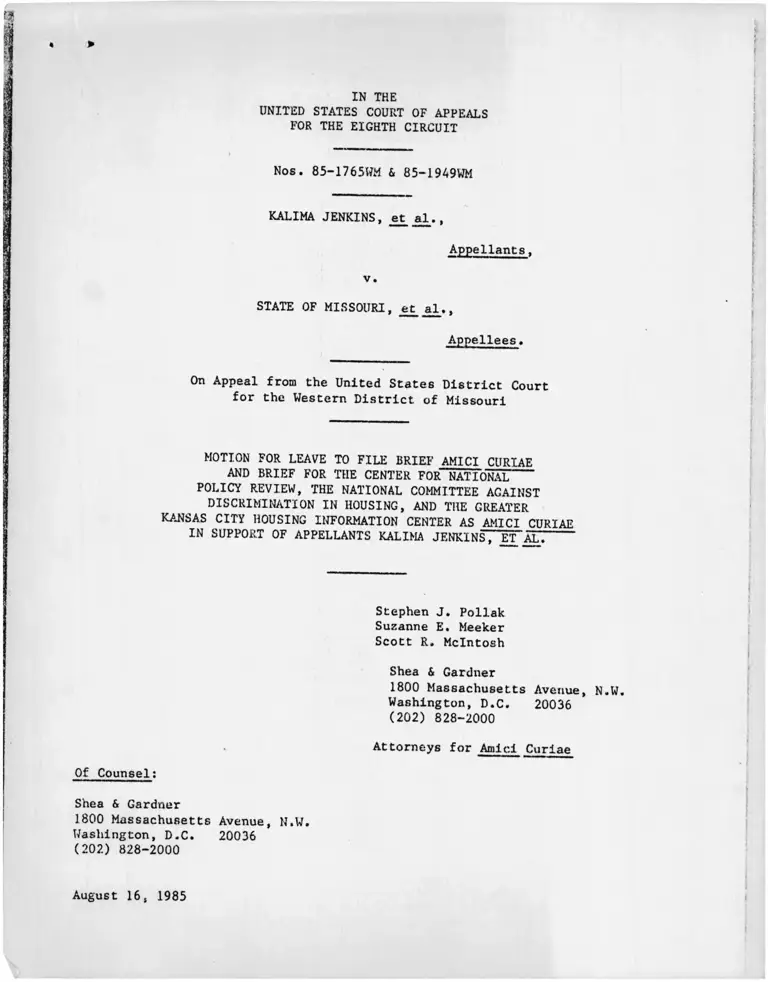

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-1765UM & 85-1949WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et al.t

Appellants.

v.

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al.t

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Missouri

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF FOR THE CENTER FOR NATIONAL

POLICY REVIEW, THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE ACAINST

DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING, AND THE GREATER

KANSAS CITY HOUSING INFORMATION CENTER AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINST ET aH ----

Stephen J. Poliak

Suzanne E. Meeker

Scott R. McIntosh

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

. Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Of Counsel:

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

August 16, 1985

- i -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.........................

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE.............

BRIEF FOR THE CENTER FOR NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW THE

NATIONAL COMMITTEE AGAINST DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING

AND THE GREATER KANSAS CITY HOUSING INFORMATION CENTER

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINS ET AL. *

I. WHERE RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING BY

STATE AND FEDERAL AGENCIES PERPETUATES

SEGREGATED SCHOOLS, THOSE AGENCIES HAVE AN

OBLIGATION TO REMEDY THEIR PAST WRONGS

AS PART OF A SCHOOL DESEGREGATION DECREE...........

H . HUD AND ITS PREDECESSOR AGENCIES HAVE ENGAGED

IN UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DISCRIMINATORY POLICIES

THAT HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO THE PRESENT DUAL

HOUSING MARKET IN THE KANSAS CITY AREA.............

A. HUD and Its Predecessor Agencies Have

Violated the Fifth Amendment by Engaging

in Purposeful Racial Discrimination and

and by Knowingly Supporting Racial

Discrimination by Other Housing Agencies

in the Kansas City Metropolitan A r e a . ,

1. Discriminatory FHA Appraisal Policies......

2. Federal Support of Discriminatory Public

Housing...... ........... .........

3. Federal Support of Discriminatory

Relocation.............................

B. The Segregatory Policies of HUD and Its

Predecessor Agencies Have Contributed

Substantially to the Continuing Dual

. Housing Market in the Kansas City Area..........

ii

vi

2

7

8

8

11

16

17

CONCLUSION 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases;

Adams v. United States. 620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir. 1980)....... .

Arthur v. Nvquist, 415 F. Supp. 904 (W.D.N.Y. 1976)..........

Barrows v. Jackson. 346 U.S. 249 (1953)................

~'l977)V * Starkvllle Academy. 442 F. Supp. 1176 (N.D. Miss.

Bolling v. Sharpe. 347 U.S. 497 (1954)........................

Brown v. Board of Educ.. 347 U.S. 483 (1954)...............

Brown v. Board of Educ.. 349 U.S. 294 (1955)...........

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board. 190 F. Supp. 861

(E.D. La. 1960), aff'd. 366 U.S. 212 (1961).................

.City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center. 53 U.S.L.W.

5022 (U.S. 1985)...............'.......................

Clients’ Council v. Pierce. 711 F.2d 1406 (8th Cir. 1983)....

Cooper v. Aaron. 358 U.S. 1 (1958)...........................

Dayton Board of Educ. v. Brinkman. 443 U.S. 526 (1979).... .

^1955) H°USing Comnlsslon v » Lewis. 226 F.2d 180 (6th Cir.

Evans_v. Buchanan. 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.), aff'd.

423 U.S. 963 (1975)...........................77777.

Garrett v. City of Ham track. 503 F.2d 1236 (6th Cir. 1974)....

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority. 296 F. Supp. 907

(N.D. 111. 1969)........ .......... ........

1, 4

3

8

14, 15

2, 6

1* 2 , 8 , 11

1, 2 , 6

3

11

15

3

1

13

4

7, 14, 17

13

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority. 503 F.2d 930

(7th Cir. 1974), aff'd sub nom. Hills v. Gautreaux.

425 u . s . 284 ( 1 9 7 6 ) . . . .7 7 7 .7 7 7 7 .7 7 7 7 7 ... .7771-------- 7, 13

- ill -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - continued

Gautreaux v. Romney. 448 F.2d 731 (7th Cir. 1971).......

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery. 417 U.S. 556 (1974).......

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C.), aff'd

sub nom Colt v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971).............

Green v. County School Board. 391 U.S. 430 (1968).......

Griffin v. County School Board. 377 U.S. 218 (1964).....

Hills v. Gautreaux. 425 U.S. 284 (1976)..................

Jaimes v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority. 758 F.2d

1086 (6th Cir. 1985)....................................

Jenkins v. Missouri. 593 F. Supp 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984)....

Kelsey v. Weinberger. 498 F.2d 701 (D.C. Cir. 1974).....

Keyes v. School District No. 1. 413 U.S. 189 (1973).....

Lombard v. Louisiana. 373 U.S. 267 (1963)................

Mingo v. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

et al•» C.A. No. H-77-1626 (S.D. Texas, filed

April 20, 1980).........................................

National Black Policy Ass'n y. Velde. 712 F.2d 569

(D.C. Cir. 1983), cert, denied. 52 U.S.L.W. 3791 fTT.s.

1984).............77777.777777.....................................

Norwood v. Harrison. 413 U.S. 455 (1973)................. .

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Board of Educ.. 368 F. Supp. 143

(W.D. Mich. 1973), aff'd, 508 F.2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975)...................... .

Otero v. New York City Housing Authority. 484 F.2d

1122 (2d Cir. 1973)....................................

14

2, 3, 6

14

14

3

vii

vii, 13, 14

passim

14, 17

4

11

vii

14, 15

14, 15, 17

3, 10

13

Palmore v. Sldoti. 52 U.S.L.W. 4497 (U.S. 1984) 10

- iv -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - continued

Poindexter v. Louisiana Fin. Assistance Co™n'n,

1* SuPP* 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff'd. 389 U.S. 571

Reed v. Rhodes, 607 F.2d 714 (6th Cir. 1979), cert.

denied. 445 O.S. 935 (1980)................ .77777..

Reed v. Rhodes, 662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981), cert.

denied. 455 U.S. 1018 (1982)................ .77777..

Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 D.S. 1 (1948)..................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educ.. 402 D.S. 1

Tedder v. Housing Authority of Paducah. 574 F. Supp. 240

(W.D. Ry. 1983)..................... ............ \.....

United States v. American Institute of Real Estate

-Appraisers, 442 F. Supp. 1072 (N.i). 111. 1977).......

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs. 456 F. Supp.

183 (S.D. Ind. 1978), aff1d in part and vacated in

-E?rt 837 F.2d 1101 (7th Cir.) cert, denied. 449 u7s.

United States v. Board of School Cftmni'rc, ^73 F.?d

400 (7th Cir. 1978)..... 7............

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs. 637 F.2d

1101 (7th Cir.), cert, denied. 449 U.S. 838 (1980)....

United States v. City of Parma. 494 F. Supp. 1049

(N.D. Ohio 1980), aff'd in part and rev’d in part

on other grounds, 661 F.2d 562 (6 th Cir. 1981)777.....

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency. 467 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972)77................................

United States v. Yonkers Board of Educ.. No. 80 CIV 6761

(S.D.N.Y., Mar. 19, 1984)...................

3

10

14

8, 9, 17

4

13

19

3

4, 5

5

10, 19

3

6

- V -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - continued

Pnlted States v. Yonkers Board of Educ.. 518 F. Sunn.

191 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)...... ........... ............ m\____

Watson v. Memphis. 373 U.S. 526 (1963)................ ...

Weiss v. Leaon. 225 S.W. 2d 127 (Mo. 1949)...............

Toung_v. Pierce, No. P-80-8-CA (E.D. Tex. July 31, 1985).,

Constitution and Statute:

Constitution of the United States:

Fif th Amendment.......................

Fourteenth Amendment.....................

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended:

Title VI...................................

Miscellaneous:

Center for National Policy Review, Breaking Down

Barriers: New Evidence on the Impact of Metropolitan

School Desegregation on Housing Patterns (Nov. 1980)......

Center for National Policy Review, Fair Mortgage Lendine:

A Handbook for Community Groups (July 1978)....'....... n“

Center for National Policy Review, “School and Residential

Desegregation, Vol. VII, No. 1, Clearinghouse for Civil

Rights Research (Spring 1979)..............................

Dee & Huggins, Models for Proving Liability of School

and Housing Officials in School Desegregation Cases

23 Urban L.J. Ill (1982)..... ........................

Note> Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Interdistrict

School Desegregation Remedies. 93 Yale L . j f w ) M Q t n v

A, 5

6

8

14, 15

passim

passim

16, 17

vii

vii

vii

5

5

Rule 29, Fed. R. App. P vi

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-1765WM & 85-1949WM

KALIMA JENKINS, et al..

Appellants.

v.

STATE OF MISSOURI, et al..

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Missouri

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINS. ET AL.

The Center for National Policy Review ("CNPR"), National Committee

Against Discrimination in Housing ("NCDH"), and the Greater Kansas City Housing

Information Center ("Center") hereby move, pursuant to Rule 29 of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure, for leave to file the attached brief amici curiae

in the above-captioned appeals.

The Center for National Policy Review is a nonprofit research and

advocacy organization affiliated with the Catholic University School of Law in

Washington, D.C., and dedicated to the pursuit of efforts to end discrimination

against minorities, women and the handicapped. Since its inception in 1970, one

of CNPR’s primary activities has been to seek to ensure that federal housing and

community development assistance programs counteract rather than reinforce segre

gation. Drawing upon its experience, CNPR has published legal and social science

- vi -

- vii -

studies on many issues, including fair housing, equal educational opportunity and

the link between discriminatory housing practices and public school segrega

tion. /

The National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing is a private,

nonprofit organization founded in 1950 to pursue the elimination of discrimina

tion in housing and the promise of equal housing opportunity nationwide. During

the 1950s and 1960s, NCDH worked for enactment of local, state, and federal fair

housing laws. Since that time NCDH has focused its efforts on promoting enforce

ment of these laws and toward that end has frequently litigated, either as coun

sel of record or as amicus curiae, issues involving alleged discrimination in

2/HDD-assisted programs.

The Greater Kansas City Housing Information Center, which began opera

tions in 1969, provides assistance to persons in the Kansas City metropolitan

area who are experiencing housing problems, including particularly discrimination

in the sale or rental of housing. Through its efforts to assist low- to

moderate-income families in their search for affordable housing, the Center has

become well versed in the barriers to housing for minorities outside of the areas

in Kansas City where they have historically resided and in the role that public

agencies and programs play in the continuation of those barriers.

— lg-lr- Mortgage Pending: A Handbook for Community Groups (July 1978)* Breaking

Down Barriers;— Ngw Evidence on the Impact of Metropolitan School Desere^ r - ! ™ ^ '

on Housing Patterns (Nov. 1980): "Sehnnl P^,'cgrcgatlo/ . * ■

V°l. VII» No. 1, Clearinghouse for Civil Rights Research (Spring 1979).’

2/ See, e.g., Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 D.S. 284 (1976); Jaimes v. Toledo

ggtropolitan Authority, 758 F.2d 1086 (6th Cir. 1985); Mingo v. Se^etarv of

f priin20an? 9 ^ ) an DeVel0?ment:> ^ 1 ^ * ' C*A* No* H-77-1626 (S.D. Texas, filed

- viii -

These three organizations seek leave of this Court to file the attached

brief amici curiae because the decision of the Court below absolving the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development ("HUD") of any responsibility for the

existing dual housing market and its segregatory effects on schooling in the

Kansas City area could have a broad impact. The housing patterns in Kansas City

and the role played in the development of those patterns by HUD and its predeces

sors and by the housing programs of state and local public agencies which it has

funded are similar to those found in many other metropolitan areas. Thus, the

decision of the lower Court could affect the achievement of equal opportunity in

education and housing well beyond the instant community.

In the attached brief, the amici address the facts and law respecting

the responsibility of HUD and the agencies whose housing programs it originated

and funded for the existing dual housing market in the Kansas City area and the

segregatory effects of that market upon area school systems. First, we analyze

the applicable cases respecting the duties of public agencies under the

Constitution when their discriminatory actions help to perpetuate unconstitu

tional dual school systems. We then review for the Court the most relevant facts

respecting the history and present segregatory effects of racially discriminatory

conduct by HUD and its predecessor agencies as well as the related state and

local public authorities funded by HUD. We believe that this analysis will be of

assistance to the Court in reviewing the decision of the District Court in light

of the record respecting the housing facts and the pertinent law.

Wherefore, the Center for National Policy Review, the National

Committee Against Discrimination in Housing, and the Greater Kansas City Housing

- ix -

Information Center move the court for leave to file the attached brief amici

curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

Poliak

Meeker

Scott R. McIntosh

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Attorneys for the Center for National

Policy Review, the National Committee

Against Discrimination in Housing, and the

Greater Kansas City Housing Information

Center

Of Counsel;

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

August 16, 1985

I

BRIEF FOR THE

CENTER FOR NATIONAL POLICY REVIEW,

THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE AGAINST DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING

AND THE GREATER KANSAS CITY HOUSING INFORMATION CENTER AS

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS KALIMA JENKINS, ET AL.

In 1954, when the United States Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of

Educ^, 347 U.S. 483 ("Brown I"), the Kansas City, Missouri, School District

( KCMSD ) and the defendant suburban school districts were operating racially

segregated, dual school systems under the mandate of the State of Missouri.

Jenkins, v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485, 1488 (W.D. Mo. 1984); see Adams v. United

Ŝtates, 620 F.2d 1277, 1280 (8th Cir. 1980). Although the State and the KCMSD

are under an affirmative constitutional duty to disestablish segregated schools,

Brown v. Board of Educ.. 349 U.S. 294, 301 (1955) ("Brown II"), the dual school

system in the KCMSD has never been dismantled. 593 F. Supp. at 1491, 1493,

1504. Moreover, the State of Missouri and the KCMSD engaged in post-1954 acts

that maintained and perpetuated the dual school system. 593 F. Supp. at 1493-94

(neighborhood schools, attendance zones, transfers, and intact busing). Each act

that has perpetuated the racially segregated, dual school system has "com

pound led]" the original constitutional violation, since "[pjart of the affirma

tive duty * * * is the obligation not to take any action that would impede the

process of disestablishing the dual system and its effects." Dayton Board of

Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 538 (1979) ("Dayton II").

The record in this case shows, however, that it is not only the actions

of the KCMSD and the Missouri educational authorities that have perpetuated the

dual school system. The discriminatory housing practices of the federal and

state governments and their agencies have established a dual housing market based

on race that continues to the present day and contributes to segregated public

education throughout the Kansas City area. See 593 F. Supp. at 1491, 1497-99,

1503 (State and state—created agencies).

- 2 -

In Part I of this brief, we review the significance of governmental

discrimination in housing to a school desegregation case. Racially discrimi

natory conduct of a federal housing agency that helps to maintain an unconstitu

tional dual school system gives rise to an affirmative duty to help disestablish

that dual school system through housing conduct. In Part II, we show that HDD

and its predecessor agencies have engaged in purposeful racial discrimination and

have knowingly supported racial discrimination by other housing agencies in the

Kansas City area, in violation of the Fifth Amendment. These discriminatory

policies and practices have contributed substantially to the present dual housing

market in the Kansas City area and, accordingly, to the existing dual school sys

tem in the KCMSD. The District Court therefore erred in dismissing HDD, and the

case should be remanded for a determination of appropriate relief.

I. WHERE RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HODSING BY

STATE AND FEDERAL AGENCIES PERPETDATES

SEGREGATED SCHOOLS, THOSE AGENCIES HAVE AN

OBLIGATION TO REMEDY THEIR PAST WRONGS AS

PART OF A SCHOOL DESEGREGATION DECREE.

Since Brown I, Brown II, and Bolling v. Sharpe. 347 D.S. 497 (1954), it

has been clear that the states and the federal government violate the

Constitution when they take steps that segregate or fail to desegregate

schools. HDD argued to the District Court that, quite apart from the question

whether its conduct in Kansas City was unconstitutionally discriminatory, as a

housing agency it should not be held liable in this school case because it is the

school authorities who are responsible for segregated schools. - The Supreme

Court has made clear, however, that "[a]ny arrangement, implemented by state

1/ HDD Mem. in Support of Mot. for Dismissal under Rule 41(b) (filed Mar. 6

1984) at 6. The State, in contrast to HDD, contended only that the present pat

tern of residential segregation could not be attributed to its past conduct. See

593 F. Supp. at 1489.

- 3 -

officials at any level, which significantly tends to perpetuate a dual school

system, in whatever manner, Is constitutionally impermissible.- Gilmore v. city

— °tf°"erT' 417 D -S’ 556' 566 <1S74> < 1 * 7 Darks Board policy permitting peri

odic exclusive use of parks by segregated private schools end affiliated groups

held unconstitutional, in part because it impeded school desegregation); accord.

COOEST v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 17 (1558) (state cannot indirectly nullify constitu

tional rights "through evasive schemes for segregation whether attempted

•ingeniously or ingenuously"). Federal courts therefore have invalidated myriad

strategies that intentionally perpetuate dual systems through the allocation of

authority among state agencies. See, e ^ , Griffin v. County School Bn.-s 377

B.S. 218 (1964) (tuition aid program for private school students; public schools

closed); Poindexter v. Louisiana Fin. Assistance Comm'n. 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D.

La. 1967), affM, 389 U.S. 571 (1968) (.per curiam) (tuition grant program);

— - leaM Parlsh Sch°o1 Boarj- 19° F- Supp. 861 (E.D. La. 1960), affd. 366

U.S. 212 (1961) (^er curiam) (removal of local school board access to bank

accounts), simply put, a state under a constitutional duty to desegregate can

neither use its non-school agencies to eviscerate efforts to dismantle a dual

system nor rely on the actions of its non-school agencies to defend the segre

gated condition of its schools as the product of factors over which it (or a

local school board) does not have control. ~

segregation specifically on grounds that government dlfcrtaL«Ion in C f “ i

responsible in substantial part for racial residential £ « e ™ “ S« °“c *

Dotted State, v. Texas Educ. Agency■ 467 F.2d 848, 863-64 n.22 (5th cir- ^ ^ 1

(en banc); United States v. Board of School Comm’rs. 456 F. Suon i,i „

?7rh ^ f'd ln M r t a°d gaeal:ed in cart on other grounds m a n F’2d lim 'D '(7th Cir. 1980); Arthur V . N^guist, 415 F. Supp. 904, 969 («.[ , ,

v- Kalamazoo Board of Educ. 368 F. Supp. 143 183 (W D B r i n , : OliverF.2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974). ’ l -D‘ Mlch- 197D . affM, 508

- A -

For these reasons, governmental housing agencies that implement segre

gative policies affecting public schools may not escape liability for the impact

of those policies on the schools on the ground that the schools are not within

their jurisdiction. The federal courts have often noted the close reciprocal

relationship between residential patterns and the racial makeup of the schools.

See Keves_ v. School Dlst. No. 1. 413 U.S. 189, 202 (1973); Swann v. Chariotte-

Mecklenburfi Board of Eduo, 402 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1971); Adams v. United States.

—U-F a» 620 F.2d at 1291; United States v. Board of School Comm'rs. 573 F.2d 400,

408 (7th Cir. 1978); Evans v. Buchanan. 393 F. Supp. 428, 434-35 (D. Del.)

(3-judge court), aff'd, 423 U.S. 963 (1975). Here, the District Court found that

there is an inextricable connection between schools and housing." 593 F. Supp.

at 1491 (emphasis added). Segregative government housing policies in an area

like Kansas City thus "compound*' the original constitutional violation and

impede the process of disestablishing the dual [school system] and its

effects." Dayton II, supra. 443 U.S. at 538.

Accordingly, the discriminatory conduct of governmental housing offi

cials has been considered to be actionable as a contributing cause of school

segregation. In United States v. Board of School Comm'rs, supra. 573 F.2d at

408-09, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held:

if residential segregation results from current or past

segregative housing practices, * * * [and] the state has

Par"ĥ cipated in or contributed to these segregative housing

practices * * *, it can be said that the state has caused,

at least in part, the segregation in schools."3/

3/ See also United States v. Yonkers Board of Educ.. 518 F. Supp. 191 193- qa

196-97 (S.D.N.Y. 1981) (Justice Department sued City Community Development

Agency for housing relief connected to school desegregation). The school board

Itself, of course, may be one of the governmental actors contributing to residen

ts*1 segregation. See, e.g., Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1. supra. 413 U.S. at

202; Swann v. Charlotte—Mecklenburg Board of Educ., supra. 402 U.S. at 20-21.

(Footnote Continued)

- 5 -

That Court went on to rule that housing agencies could be held responsible for

school segregation upon the following proof:

(1) [T]hat discriminatory practices have caused segrega—

tive residential housing patterns and population shifts;

(2) that state action, at whatever level, by either direct

or indirect action, initiated, supported, or contributed to

these practices and the resulting housing patterns and

population shifts; and (3) that although the state action

need not be the sole cause of these effects, it must have

had a significant rather than a de minimis effect." Id.

The Court subsequently affirmed a school decree that included injunctive relief

against the Indianapolis housing authority. 637 F.2d 1101 (7th Cir. 1980).

Where the present effect of discriminatory governmental housing prac

tices assists the perpetuation of a dual school system, that impact warrants

appropriate housing relief to facilitate school desegregation. Under such cir

cumstances, the vestiges of dual schools in areas like Kansas City cannot be dis

mantled without some affirmative effort to dismantle the dual housing market as

well. Governmental agencies which have engaged in segregatory housing conduct

therefore are appropriately charged with an affirmative duty to disestablish the

dual housing market to the extent feasible, in order to help remedy the school

consequences of that conduct. The nature of this duty is suggested by

JI?Afed States v. Yonkers Board of Educ., supra. where HUD was named a third-party

defendant. The claims against HUD, based on its discriminatory housing practices

contributing to segregated schools, were settled by a consent decree requiring

HUD to take affirmative steps to promote the integration of the white area of

Yonkers through, among other things, construction of new public housing and issuance

Some commentators have suggested that proof of governmental discrimination

with respect to housing alone could justify school desegregation relief. E.g.

Note* Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Interdistrict School DesegregaTT^*

_ ?P.£dies» 93 Yale L.J. 340 (1983); Dee & Huggins, Models for Proving Liability of

School and Housing Officials in School Desegregation Cases. 23 Urban L . .T . ni^ -------

147-56 (1982). The instant appeals, however, do not require this Court to decide

whether housing violations alone may establish school liability.

I

(•

►

I

!

of conditional rent-assistance certificates. No. 80-CIV-6761, slip. 0p. (S.D.N.Y

Mar. 19, 1984) (approving and setting out consent decree).

HUD may argue that, even if state or local housing authorities have an

affirmative constitutional obligation in appropriate circumstances to assist in

disestablishing a dual school system, HUD is free from any affirmative responsi

bility because it is not an instrumentality of the state government that

originally established that dual system. This argument should be rejected.

Since Brown II, it has been clear that where the United States and its agencies

have acted to establish or to perpetuate a racially dual school system, the Fifth

Amendment imposes on the United States an affirmative duty to dismantle every

vestige of that school system. See Bolling v. Sharpe. 347 U.S. 497, 500 (1954)

( In view of our decision that the Constitution prohibits the states from main

taining racially segregated public schools, it would be unthinkable that the same

Constitution would impose a lesser .duty on the Federal Government."). The amici

submit that this affirmative federal duty also exists where agencies of the

United States have acted so as to perpetuate a state-sponsored dual school system

by their intentionally discriminatory housing policies. As we now show in

Part II, the federal government, through intentional housing discrimination in

the Kansas City area, has perpetuated the unconstitutional dual school system

established by the State of Missouri. Under these circumstances, the federal

government, like the State, can be held responsible for the effects of its con

duct and can be ordered to take appropriate action to remedy those effects. —

4/ The affirmative duty to disestablish segregative institutions is not of

course, limited to schools. As the Supreme Court explained in Gilmore v! Citv nf

Montgomery, supra, a government is "under an affirmative constitutional dutv to—

eliminate every 'custom, practice, policy or usage' reflecting an ’impermissible

nScCe t0cS e^ ° y Choroughly discredited doctrine of 'separate but equal.417 U.S. at 566-67 (quoting Watson v. Memphis. 373 U.S. 526, 538 (1963)) This

affirmative obligation has been imposed on HUD and other housing authorities when

(Footnote Continued)

- 7 -

II. HUD AND ITS PREDECESSOR AGENCIES HAVE ENGAGED

IN UNCONSTITUTIONALLY DISCRIMINATORY POLICIES

THAT HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO THE PRESENT DUAL

HOUSING MARKET IN THE KANSAS CITY AREA.______

The evidence introduced at trial by the plaintiffs and the KCMSD showed

that the State of Missouri and Btate and local agencies have engaged in a variety

of discriminatory housing policies that have contributed to the present dual

housing market in the Kansas City area. See 593 F. Supp. at 1495-1503. The

plaintiffs also introduced extensive evidence that HUD and its predecessor agen

cies not only were aware of these discriminatory policies but participated in

them and supported them financially over a forty-year period. The District Court

recognized the discriminatory nature of the state housing policies, and in gen

eral acknowledged the degree of federal involvement in those policies, but none

theless concluded that none of the practices of HUD and its predecessors ran

afoul of the Constitution. Id. at 1495-1501. The Court also concluded that the

present effects of the most egregious form of federal discrimination, the

appraisal practices of the FHA, were at most de minimis. Id. at 1497.

Although the plaintiffs and the KCMSD introduced evidence that a wide

variety of federal housing programs had discriminatory consequences, we believe

the District Court's errors are most clear with respect to three categories of

federal housing policies and practices: (1) the FHA's use of racially discrimi

natory mortgage appraisal standards; (2) HUD's knowing financial support for the

they have been found to be in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments by

their purposefully discriminatory conduct. See, e.g., Garrett v. City of

Hamtramck, 503 F.2d 1236, 1247 (6th Cir. 1974) (where HUD violated Fifth

Amendment " [b]y failing to halt a city program where [it was aware] discrimina

tion in housing was being practiced and encouraged, * * * HUD is properly held to

be jointly liable with the City for an affirmative program to eliminate discrimi

nation from that project."); Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority. 503 F.2d

930, 939 (7th Cir. 1974) (constitutional violation by HUD required "adoption of

comprehensive metropolitan area plan that will not only disestablish the segre

gated public housing system * * * but will increase the supply of dwelling units

as rapidly as possible"), aff'd sub nom. Hills v. Gautreaux. 425 U.S. 284 (1976).

- 8 -

discriminatory siting and tenant assignment policies of the Housing Authority of

Kansas City ("HAKC"); and (3) HDD's parallel support for the discriminatory

relocation practices of the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Agency ("LCRA"). We

show that the federal government's conduct in each category violated its estab

lished duties under the Fifth Amendment, and that these violations have had a

significant continuing impact on present residential segregation in the Kansas

City area.

A. HUD and Its Predecessor Agencies Have Violated the Fifth

Amendment by Engaging in Purposeful Racial Discrimina

tion and by Knowingly Supporting Racial Discrimination

by Other Housing Agencies in the Kansas City Area,______

1* Discriminatory FHA Appraisal Policies. As the District Court

recognized, the State of Missouri maintained residential segregation by judi

cially enforcing racially restrictive covenants both before and after the Supreme

Court's decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). 593 F. Supp. at

1497. — The unconstitutionality of this policy of enforcing racial covenants

was settled in 1948 in Shelley and was not contested below. The Court found not

only that Missouri’s enforcement of racial covenants worked to segregate the

Kansas City housing market prior to Shelley and Brown I, but also that this

policy has had a continuing effect on Kansas City's dual housing market to the

present day by "placing the State’s imprimatur on racial discrimination" and

5/ Missouri courts continued to award damages for breaches of racial covenants

until 1953, five years after Shelley. Compare Weiss v. Leaon, 225 S.W.2d 127

(Mo. 1949), with Barrows v. Jackson. 346 U.S. 249 (1953). In addition to the

enforcement provided by the Missouri courts, the Missouri Real Estate Commission

disciplined realtors who sought to sell property to blacks in racially restricted

neighborhoods. T13,041-42 (Tobin).

The foregoing "T___" reference is to the consecutively numbered pages of the

trial transcript followed by the name of the witness in parentheses; "X "

references are to plaintiffs' exhibits in the record unless otherwise indicated;

and references to pages in particular depositions include the deponent's name

followed by "Depo. ___ " indicating the page number of the deposition.

- 9 -

'encourag[ing] racial discrimination by private individuals in the real estate

* * * i n d u s t r [ y ] I d . at 1503.

Although the District Court recognized that the federal government

participated in this state-enforced system of residential segregation through the

mortgage appraisal policies of the FHA, 593 F. Supp. at 1497, the Court mis

takenly disregarded the FHA’s affirmative encouragement of racial covenants and

other restrictive practices. From the FHA’s inception in 1934 through 1947, the

FHA’s underwriting manuals stressed the desirability of racial covenants, limited

the availability of mortgage insurance for new subdivisions that were not subject

to racial covenants, and downgraded appraisals in neighborhoods undergoing racial

integration. X1303-04. The FHA removed explicit racial references from its

underwriting manuals after 1947, but continued for over a decade thereafter to

stress the importance of "compatability among neighborhood occupants- and

required appraisers to take account of the presence of "mixture[s] of user

groups" that might "render the neighborhood less desirable to present and pros

pective occupants." X1305-1307, 1310. Testimony established that the FHA’s

post-1947 encouragement of "compatible" neighborhoods was understood to be a

continuation of its prior reliance on overtly racial considerations. T14,864,

15,199-201 (Orfield); T13,057-58 (Tobin). Although the FHA formally adopted a

policy in 1950 of not underwriting mortgages on properties subject to post-1949

racial covenants, the District Court disregarded testimony that the FHA continued

to refuse to underwrite loans in the Kansas City area for properties without

racial covenants until President Kennedy issued Executive Order 11063 in 1962,

fourteen years after Shelley. Thompson Depo. 73-76, 85-86.

The FHA's pronouncement of racially discriminatory appraisal standards

had a significant impact on the Kansas City housing market. The FHA underwrote

roughly 20Z of the single-family homes in the Kansas City area, and its influence

10 -

extended even further because private builders developed and marketed entire

subdivisions to comply with FHA standards even if some of the units ultimately

were not financed through the FHA. 114,044-45, 15,217, 15,639-40 (Orfield).

Equally important, the FHA's discriminatory appraisal standards were adopted as

national standards by the private lending and appraisal industries. 114,850-53

(Orfield); T13,078-81 (Tobin); X1310C, 2960. ~ More generally, the FHA's

endorsement of residential segregation significantly influenced how whites and

blacks viewed residential segregation and integration. 114,858-59 (Orfield). As

a result, blacks and whites in the Kansas City area felt the effects of the FHA's

discriminatory standards even in housing transactions in which the FHA did not

formally participate.

The invidious nature of the FHA's original appraisal policies has been

recognized by the courts. See, e.g., Reed v. Rhodes. 607 F.2d 714, 729 (6th Cir.

1979); United States v. City of Parma, 494 F. Supp. 1049, 1058 (N.D. Ohio 1980),

aff'd in part and rev'd in part on other grounds. 661 F.2d 562 (6th Cir. 1981);

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Board of Educ.. supra. 368 F. Supp. at 182-83. In exonerat

ing the FHA’s conduct on the ground that the FHA acted neither "arbitrarily nor

capriciously in giving [racial] covenants consideration in arriving at an

appraisal," 593 F. Supp. at 1497, the District Court disregarded both the nature

of the FHA's conduct and the constitutional standards applicable to that con

duct. Not only did the FHA give private discrimination "consideration" in its

own conduct, but it also intentionally encouraged private owners and developers

to engage in discrimination in order to obtain FHA financing. The Constitution

6/ By the FHA's own admission, no national appraisal standards existed when the

agency was founded in 1934 and the FHA itself had to establish standards for

assessing "sound properties and neighborhoods." X2960 at 10. In the FHA's

words, "[1]ending agencies and appraisers have viewed each edition of the FHA

Underwriting Manual as an authoritative book on mortgage lending." X1310C.

11

does not excuse either reliance on residential segregation or encouragement of it

as a "rational" governmental response to private racial biases. See Palmore v.

Sldoti, 52 U.S.L.W. 4497, 4498 (U.S. 1984) ("Private biases may be outside the

reach of the law, but the law cannot, directly or indirectly, give them effect");

accord, City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, 53 U.S.L.W. 5022, 5026 (U.S.

1985); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267, 273 (1963).

2. Federal Support of Discriminatory Public Housing. Public housing

in Kansas City has been intentionally segregated through much of its history.

HAKC employed deliberately discriminatory siting and tenant assignment policies

from before Brown I until at least 1964. — ■ Prior to 1958, HAKC maintained sepa

rate white housing projects sited in white neighborhoods and black projects sited

in black neighborhoods. T9,999-10,001; Bridges Depo. 59. HAKC purported to

abandon its race-based tenant assignment policy in 1958, but it used administra

tive means to maintain segregated assignments until at least 1964. Bridges Depo.

10-11. During this period of formal racial segregation in siting and tenant

selection and assignment, HAKC constructed seven family public housing projects

in Kansas City, all within a fourteen-block area of the inner city, containing

over 2100 units. 593 F. Supp. at 1498; Bridges Depo. 21-22.

HUD and its predecessor agency, the Housing and Home Finance

Administration ("HHFA"), provided financial support for HAKC throughout this

8 /period. “ HHFA was informed of the segregated nature of HAKC housing no later

than 1954, and HHFA and HUD were apprised of its segregated character regularly

JJ The District Court erred in stating that "[a]t the outset HAKC followed the

'freedom of choice plan.'" 593 F. Supp at 1498.

8J Between 1942 and 1976, HUD and its predecessors provided HAKC with over $54

million in construction and operating funds. X1595.

12 -

thereafter. “ Despite this longstanding knowledge of HAKC's conduct, neither

HHFA nor HUD made any effort until 1967 to prevent HAKC from discriminating in

its siting and tenanting policies, much less any effort to require HAKC to undo

the existing segregation engendered by those policies. HHFA's original policy,

adopted in 1939 and reiterated in 1951, was to allow local housing authorities to

distribute public housing on a racial basis. X1591, 1596XX. Thomas Webster, an

HAKC Commissioner from 1948 to 1960, complained to HHFA about HAKC's discrimina

tory actions throughout his tenure, but HHFA declined to take any action.

19,947-49. HHFA found in 1962 that three projects were completely segregated and

that while one project had made progress toward integration, the HAKC Board of

Commissioners had instructed HAKC staff to "proceed cautiously" in integrating

the projects. X1641F. Despite these findings, HHFA concluded that the desegre

gation process was working and did not recommend that any action be taken. Id.

In 1963, HHFA required public housing authorities to adopt nondiscriminatory

tenant assignment standards for public housing projects es-tablished after 1962,

but it failed to require the adoption of nondiscriminatory standards for existing

projects. X1596XX.

In 1967, HUD found that HAKC's "freedom of choice" tenant assignment

policy, which HAKC had put into practice in 1964, Bridges Depo. 10-11, "actually

fostered segregatory tenant selection and assignment policies." XFD105. HUD

then persuaded HAKC to require prospective tenants to choose from among the three

projects with the highest vacancy rates or be placed at the bottom of the waiting

list. Id. However, HAKC failed altogether to comply with this assignment policy

9/ HHFA and HUD received reports showing the segregated status of HAKC housing

projects in 1954 (T9,955), 1955 (X1641), 1962 (X1641F), 1969 (X1596III), 1971

(X382, X1596JJJ), 1975 (X1596LLL), 1976 (X1639), 1977 (XFD 132), 1978 (X1611),

and 1981 (X1610).

and instead maintained a "freedom of choice” policy for almost a decade longer.

Bridges Depo. 52-53. HUD found HAKC to be violating its 1967 selection plan as

early as 1969, but failed to require HAKC to abandon its "freedom of choice" plan

and did not conduct a formal investigation of HAKC’s tenant policies again until

1976. XFD105. HUD and HAKC eventually entered into a new compliance agree

ment in 1977, which created a limited minority assignment preference but also

allowed prospective tenants to choose in which project they would live, and HAKC

housing projects remained racially identifiable thereafter. X1596GGG, X1611

(1978), X1610 (1981).

Although the District Court did not address the validity of HAKC’s

racially discriminatory siting and tenant selection and assignment policies, the

unconstitutionality of those policies is plain. See, e.g., Detroit Housing

Commission v. Lewis, 226 F.2d 180 (6th Cir. 1955); Tedder v. Housing Authority of

Paducah, 574 F. Supp. 240, 245 (W.D. Ky. 1983); Gautreaux v. Chicago Rousing

Authority, 296 F. Supp. 907 (N.D. 111. 1969). Having built and maintained inten

tionally segregated public housing in Kansas City, HAKC thereafter was constitu

tionally obligated not only to cease its segregatory policies but to adopt tenant

policies that eliminated the segregated condition of Kansas City public hous

ing. See Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, supra. 503 F.2d at 939; Otero

v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F.2d 1122, 1133 (2d Cir. 1973). As a

result, HAKC’s subsequent reliance on a "freedom of choice" assignment policy

that HUD found to perpetuate past segregation was itself unconstitutional. See

Jaimes v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority. 758 F.2d 1086, 1090-92, 1101,

12/ In the intervening years, HUD found that HAKC's housing projects remained

racially identifiable but failed to take corrective action. X382, 1596JJJ.

Indeed, in 1975, HUD actually found that HAKC's "freedom of choice" plan was

acceptable because HAKC was willing to place nonminority applicants in minority

projects if they so desired. X1596LLL.

14 -

1107-09 (6th Cir. 1985); cf. Green v. County School Board. 391 U.S. A30 (1968)

("freedom of choice" plan for student assignment unconstitutional).

The District Court absolved HDD of constitutional responsibility for

its participation in HAKC's conduct on the ground that "HDD's monitoring of the

[public housing] program was neither arbitrary nor capricious and * * * the

[1977] compliance agreement entered into between HAKC and HDD was reasonable."

The Court's novel conclusion that HDD's conduct was constitutional as long as it

was "reasonable" and "neither arbitrary nor capricious” is unsound.

The Fifth Amendment prohibits HDD from knowingly funding unconstitu

tional discrimination by local housing authorities. Garrett v. City of

Hamtramck, supra. 503 F.2d at 1247; Gautreaux v. Romney. 448 F.2d 731, 737-39

(7th Cir. 1971); Young v. Pierce, No. P-80-8-CA, slip op. at 32-37 (E.D. Tex.

July 31, 1985). This rule reflects the broader principle that governmental agen

cies may not provide knowing support for racial discrimination by other institu

tions. Norwood v. Harrison. 413 D.S. 455, 467 (1973); National Black Police

Ass'n v. Velde, 712 F.2d 569, 580-83 (D.C. Cir. 1983) ("[I]t is a clearly estab

lished principle of constitutional law that the federal government may not fund

local agencies known to be unconstitutionally discriminating."); Reed v. Rhodes,

662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981); Bishop v. Starkville Academy. 442 F. Supp. 1176,

1180-82 (N.D. Miss. 1977); Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150, 1164-65 (D.D.C.)

(3-judge court), aff'd, 404 D.S. 997 (1971). Moreover, HDD's constitutional

obligation was not limited to refraining from funding local agencies that pres

ently are engaged in racial discrimination; instead, the Fifth Amendment pro

hibits the federal government from supporting agencies that have ceased actively

to discriminate but that have failed to eliminate the segregative effects of

their past discrimination. See, e.g., Kelsey v. Weinberger, 498 F.2d 701, 707-11

(D.C. Cir. 1974). By continuing to fund public housing programs in Kansas City

15 -

rithout requiring the elimination of the residential segregation intentionally

fostered by those programs, HDD therefore compounded its unconstitutional

conduct. Id.

As the Supreme Court’s decision in Norwood and its progeny make clear,

the Constitution prohibits federal funding of unconstitutional discrimination by

state agencies even if the federal government’s own purpose in providing the

funding is not discriminatory; "a government entity may not fund a discriminating

entity simply because the government’s purpose is benevolent." National Black

Ass>n v * I elde» 712 F.2d at 580; accord. Norwood v. Harrison.

-uPra» 413 D,S* at 466-67; Young v. Pierce, supra, slip op. at 36-37. As a

result, HOD's financing of the constitutional misdeeds of HAKC would have been

impermissible even if HUD’s purpose had not been to further residential segrega

tion in the Kansas City area. * 1 Were it necessary to establish intentional

discrimination, however, the pattern of HUD’s conduct -- its longstanding know

ledge of HAKC's discriminatory practices, its continued provision of funding for

those practices, and its repeated failure to take steps necessary to eliminate

the practices and their effects — is strikingly like the HUD conduct found to be

intentionally discriminatory by this Court"in Clients’ Council and by the

District Court for the Eastern District of Texas in Young. See Clients' Council

v. Pierce, .supra, 711 F.2d at 1410-23; Young v. Pierce, supra, slip op. at 14-32,

37-44.

— A panel of this Court suggested in dictum in Clients' Council v. v n

I 1406 (1983) that HUD could not be held liabl“ for funding d i s c r i ^ H ^ by

local agencies unless its own motives were discriminatory. See id. at 1409

This dictum is contrary to the Supreme Court’s decision in Norwood" and its

See> National Black Police Ass’n v. Velde, ^upra. 712 F.2d at-

581-82 (rejecting requirement of discriminatory animus by funding aeencv as

inconsistent with Norwood); Young v. Pierce, supra, slip op. at 36-37 (same)*

Bishop v. Starkville Academy, supra. 442 F. Supp. at 1180-82 (same). *

16

3. Federal Support of Discriminatory Relocation. Like the record of

Kansas City public housing, the record of relocation from Kansas City urban

renewal projects from the 1950s through the 1970s is one of intentionally dis

criminatory policies and practices by a local authority that HUD knowingly con

tinued to fund and failed to redress for an extended period of time. LCRA's

urban renewal programs were funded by HUD and its predecessors under the Federal

Housing Act of 1949 from LCRA's inception in 1953 to the present. 593 F. Supp.

at 1497-98; XFD204C, 1652. As late as 1973, LCRA employed a discriminatory relo

cation policy under which black relocatees were being relocated in black areas

within the KCMSD while white relocatees were being relocated throughout the

Kansas City area. 593 F. Supp. at 1497; T9,461-69 (Newsome); Til,388-89 (Rabin);

Til,517-25 (San Juan).

HUD's Kansas City office took no action regarding LCRA’s policies and

practices until November 1971 when it received a private complaint concerning

LCRA's relocation practices. X2659, 2676. In 1972, HUD confirmed that LCRA's

conduct violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but LCRA took no

action to discontinue its segregatory relocation practices and failed to provide

HUD with data respecting those practices in a timely fashion. 593 F. Supp. at

1497-98; X2659. Several subordinate officials in the Kansas City HUD office

urged that HUD discontinue funding of LCRA in 1973 because of its failure to com

ply with Title VI, but HUD refused to do so. Til,575-80 (San Juan); T20,713-23

(Kilbride). Instead, HUD continued funding and merely arranged for Kansas City

to assume LCRA's relocation authority after June 1973 and to provide each relo-

catee with at least one reference outside the inner city. 593 F. Supp. at

1498. At no point before or after 1973 did HUD require either LCRA or Kansas

City to take affirmative steps to eliminate the residential segregation caused by

the LCRA's past practices.

- 17 -

The District Court erred in excusing HDD's continued financial support

of LCRA. LCRA's administration of its relocation programs to steer black relo

cates to black areas and white relocatees to white areas violated not only Title

VI, as HUD found, but the Fourteenth Amendment as well. Cf. Garrett v. City of

Hamtramck, supra. By knowingly funding LCRA's discriminatory conduct, and by

failing to require LCRA and its successor agency to eliminate the segregative

consequences of LCRA's policies and practices, HUD violated its own constitu

tional obligations to "steer clear * * * of giving significant aid to institu

tions that practice racial * * * discrimination." Norwood v. Harrison, supra.

413 U.S. at 467; Kelsey v. Weinberger, supra. 498 F.2d at 707-11; see pp. 14-15,

supra.

B. The Segregatory Policies of HUD and Its Predecessor

Agencies Have Contributed Substantially to the Con-

tinuing Dual Housing Market in the Kansas City Area,

The District Court erred not only in failing to hold that the policies

of HUD and its predecessors were unconstitutional but also in failing to recog

nize their present impact on the dual housing market in the Kansas City area.

The District Court's most serious error in this regard was its finding that the

present effects of the FHA's past appraisal policies were no more than

de minimis. 593 F. Supp. at 1497. There is no serious dispute that at the time

they were in effect, both FHA's policy of encouraging residential segregation and

Missouri's policy of enforcing racial covenants had significant impacts on resi

dential segregation in the Kansas City area. Racial covenants covered a large

proportion of residential land uses in the three-county area immediately prior to

12/Shelley. T13,023-24 (Tobin). They were particularly common in areas

111 Over 1200 racial covenants were recorded in Jackson, Platte, and Clay

Counties prior to 1960. X1239, 1239A.

adjoining the black inner city, trapping blacks in deteriorating urban housing

and creating a "minefield" effect that discouraged blacks from attempting to

purchase housing in white neighborhoods even when particular neighborhood homes

were not themselves subject to covenants. T13,023-24, 13,036-37 (Tobin);

13/114,836-39 (Orfield). The FHA's role in this process was particularly

important because, as noted supra, p. 10, its discriminatory standards were not

only employed by the FHA but were widely adopted by private actors in the housing

and mortgage fields.

It is equally clear that the FHA's discriminatory appraisal policies

have had a continuing impact on the dual housing market in the Kansas City

area. As noted above, the FHA continued to insist on racial covenants in the

Kansas City area into the early 1960s. Except in the Southeast Corridor, which

provided an expansion area for the black ghetto, the residential patterns fos

tered by HDD prior to 1960 have persisted to the present: what was then white

housing has remained largely white, while then-black housing has remained

black. T13,425-26 (Tobin). As a result, the large volume of housing transac

tions that have occurred since the FHA ended its discriminatory practices has not

worked to undo the residential segregation encouraged by the FHA during the

critical suburbanization period of the 1940s and 1950s. — ' Moreover, although

the FHA eventually ceased to insure mortgages subject to racial covenants and

_1J3/ By confining blacks to the inner city and limiting the supply of housing

available to them, covenants also undermined the ability of blacks to accumulate

equity through home ownership. T14,858-59 (Orfield). Therefore, even after the

covenants were removed, blacks were disadvantaged in seeking housing in areas

outside the KCMSD.

_14/ Quite apart from the fact that housing transactions tended to be between

members of the same race, some 222 of all black homeowners and 282 of all white

homeowners in Jackson County occupied the same homes in 1980 that they had

occupied in 1960 -- placing a significant portion of Kansas City's owner-occupied

housing stock beyond the possible effects of housing turnover altogether. X3003.

19

adopted more neutrally phrased appraisal standards, the private lending and

appraisal institutions that adopted the FHA’s original discriminatory standards

in the 1930s and 1940s continued to rely on these standards as late as the mid-

1970s to justify lending policies based on neighborhood racial composition.

114,852-56, 15,204-07, 15,524-25 (Orfield); see City of Parma, supra. 494

F. Supp. at 1059; United States v. American Institute of Real Estate A ppraisers

442 F. Supp. 1072 (H.D. 111. 1977). Accordingly, the District Court's conclusion

that the FHA’s appraisal practices have had no more than a de minimis effect on

present racial housing patterns in the Kansas City area cannot be squared with

the record. —

The present impact of the FHA’s past policies on Kansas City’s dual

housing market would be sufficient even standing alone to make HUD responsible

for the segregative educational consequences of its actions. See pp. 2-6,

lupra. That impact, however, has been supplemented by the continuing segregative

effects of the discriminatory policies carried out by HAKC and LCRA and knowingly

funded by HUD. Given the high degree of exclusion of blacks from the housing

L5/ In reaching its conclusion, the District Court relied principally on a com-

E w S v ^ r S S n thean““ber FHA-financed mortgages in the KCMSD before 1950 Croughly 15,000) and the total number of housing transactions -fn nj

SMSA between 1950 and 1980 (roughly 2,000,000). 593 F. Supp. at 1497. This ^

comparison grossly overstates the impact of housing turnover on present housing

patterns. First, the 2,000,000-transaction figure includes all housing transac-

tions in the Kansas City SMSA, comprising five Missouri counties and two Kansas

counties as well, while the 15,000-transaction figure involves only the portion

a single county (Jackson) encompassed by the KCMSD. See 593 F Sunn af i/ov

T20 101-02 Second, two-thirds of the l . o S o . O O o S a c t ^ n ? ^ e r^es J n t s '

rental rather than owner-occupied transactions and thus is outside the^jwner-

occupied market in which the FHA operated. T20,101-02 (Berry) Third r>™»

parison assumes that all of the housing transactions after 1950 are free of that

“ 1”C °f ^criminatory FHA appraisal standards, yet the FHA continued to insist

on racial covenants throughout the 1950s in Kansas City. Thompson Depo. 73W6

o « « ™ / h r " P On lgnores both persistence of racial housing

FHA s S L f r d ! h°"Slng turnover and the continued reliance on discriminatory FHA standards by private actors into the 1970s. y

- 20

market outside the KCMSD, T12,978-13000 (Tobin), the consequences of siting and

tenanting over 2,000 public housing units on a discriminatory basis within the

KCMSD and steering hundreds of black relocatee-families into the KCMSD has been

to intensify residential segregation and the dual housing market in the Kansas

16/City area.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the judgment of the District Court in favor of

HUD should be reversed and this case remanded for a determination of the appro

priate relief.

Scott R. McIntosh

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Attorneys for the Center for National

Policy Review, the National Committee

Against Discrimination in Housing, and

the Greater Kansas City Housing

Information Center

Of Counsel:

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

August 16, 1985

Respectfully ̂ submitted

Poliak

Suzanne E7 Meeker

16/ The District Court found "that the relocations had no significant effect on

the racial composition of the enrollment in any [suburban school district]."

General Mem. and Order (June 5, 1984) at 37. Whatever the absolute impact of the

discriminatory relocation policies, the Court erred in evaluating those effects

in isolation from the segregatory effects of other federal housing programs.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 15th day of August, 1985, I served two

copies of the foregoing Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief for

the Center for National Policy Review, the National Committee Against

Discrimination in Housing, and the Greater Kansas City Housing Information Center

as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellants Kalima Jenkins„ et al., by overnight

express delivery to:

Bruce Farmer, Esquire

Assistant Attorney General

200 West High Street

Jefferson City, MO 65101

Eugene Harrison, Esquire

Assistant U.S. Attorney

811 Grand Avenue

Kansas City, MO 64106

On August 16, 1985, I hand delivered two copies to:

H. Bartow Farr III, Esquire

Onek, Klein & Farr

2550 M Street, N.W., Suite 250

Washington, D.C. 20037

David S. Tatel, Esquire

Allen R. Snyder, Esquire

Elliot M. Mincberg, Esquire

Patricia A. Brannan, Esquire

Hogan & Hartson

815 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

John C. Hoyle, Esquire

John F. Cordes, Esquire

Attorneys, Appellate Staff

Civil Division, Room 3127

U.S. Department of Justice

Tenth Street & Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

- 2 -

On August 16, 1985, I sent two copies by Express Mail to

Arthur A. Benson XI, Esquire

Benson & McKay

911 Main Street, Suite 1430

Kansas City, MO 64105

Julius Levonne Chambers, Esquire

James M. Nabrit II, Esquire

James S. Liebman, Esquire

Theodore M. Shaw, Esquire

Deborah Fins, Esquire

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

Michael Gordon, Esquire

1125 Grand Avenue, Suite 1300

Kansas City, M0 64106

James Borthwick, Esquire

600 Five Crown Center

2480 Pershing Road

Kansas City, M0 64108

Lawrence M. Maher, Esquire

James H. McLamey, Esquire

1500 Commerce Bank Building

922 Walnut

Kansas City, MO 64106

Gene Voights, Esquire

1101 Walnut Street

20th Floor

Kansas City, MO 64106

Julius M. Oswald, Esquire

Robert B. McDonald, Esquire

P.0. Box 550

Blue Springs, MO 64015

Hollis H. Hanover, Esquire

13th Floor Commerce Bank Building

922 Walnut

Kansas City, M0 64106

Jeffrey L. Lucas, Esquire

500 Commerce Bank Building

922 Walnut

Kansas City, M0 64106

- 3 -

Timothy H. Bosler, Esquire

Thomas Capps, Esquire

Suite 800

Westowne VIII

Liberty, MO 64068

Norman Humphrey, Jr., Esquire

123 West Kansas

Independence, MO 64050

Conn Withers, Esquire

17 East Kansas Street

Liberty, M0 64068

George Feldmiller, Esquire

Kirk T. May, Esquire

Daniel D. Crabtree, Esquire

P.0. Box 19251

Kansas City, M0 64141

Basil L. North, Esquire

North, Watson & Bryant

Suite 1201

1125 Grand Avenue

Kansas City, MO 64106

Donald C. Earnshaw, Esquire

Earnshaw & Earnshaw

23 East Third Street

Lee's Summit, MO 64063

Scott A. Raisher, Esquire

Room 431

615 E. 13th Street

Kansas City, M0 64106

Robert F. Manley, Esquire

4500 Carew Tower

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Curt T. Schneider, Attorney General

Attn: John R. Martin, Esquire

State Capitol Building

Topeka, KS 66612

John L. Vratil, Esquire

Lytle, Wetzler, Winn & Martin

P.0. Box 8030

Shawnee Mission, KS 66208

- 4 -

Earl W. Francis, Esquire

Francis & Francis

700 Kansas Avenue

Topeka, KS 66603

Jack W«R» Headley, Esquire

2345 Grand

26th Floor

Kansas City, MO 64108

P. John Owen, Esquire

1700 Bryant Building

1102 Grand Avenue

Kansas City, M0 64106

Hugh H. Kreamer, Esquire

Court Square Building

110 South Cherry

Olathe, KS 66061

Williard L. Phillips, Esquire

P.0. Box 1387

Kansas City, KS 66101

James P. Lugar, Esquire

Alpine East Building

7735 Washington Avenue

Kansas City, M0 66112