Abbot v. Thetford Brief Amicus Curiae on Appeal NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abbot v. Thetford Brief Amicus Curiae on Appeal NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1976. 349d03b4-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/757d2c83-e61a-482c-b747-8fb0e46dc2bd/abbot-v-thetford-brief-amicus-curiae-on-appeal-naacp-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

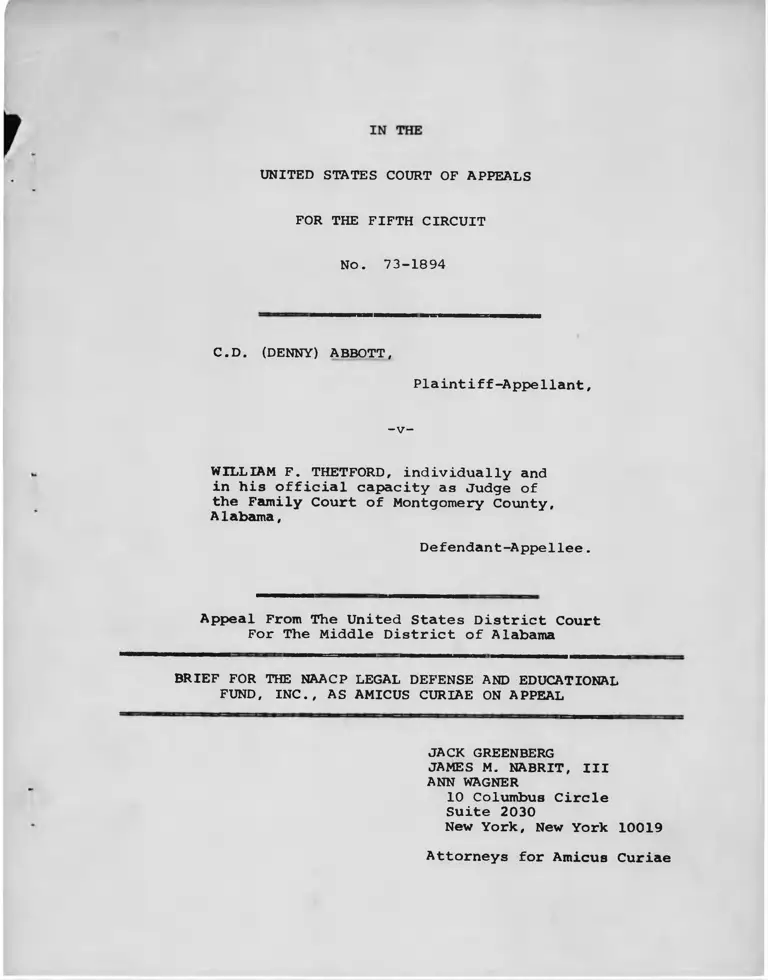

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1894

C.D. (DENNY) ABBOTT,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v-

WILLIAM F. THETFORD, individually and

in his official capacity as Judge of

the Family Court of Montgomery County, Alabama,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE ON APPEAL

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III ANN WAGNER

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

I N D E X

Page

Interest of the Amicus .............................

Argument ........................................... 3

I. IN FILING A FEDERAL LAWSUIT ON BEHALF OF

THE RIGHT OF BLACK NEGLECTED CHILDREN TO

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAW,DENNY ABBOTT

WAS EXERCISING HIS FIRST AMENDMENT FREE

DOMS OF SPEECH, PETITION AND ASSEMBLY ... 3

II. JUDGE THETFORD'S ORAL INSTRUCTION

PROHIBITING ALL JUVENILE COURT STAFF

FROM FILING xAWSUITS, WITH POSSIBLE

EXCEPTIONS, IS FACIALLY UNCONSTITUTIONALAS BOTH VAGUE AND OVERBROAD ............ 7

III. THE ORAL INSTRUCTION OF JUDGE THETFORD

WAS UNCONSTITUTIONALLY APPLED TO PRO

HIBIT AND PUNISH PRESUMPTIVELY-PROTECTED FIRST AMENDMENT EXPRESSION WITHOUT

SUBSTANTIAL AND MATERIAL DISRUPTION OF JUVENILE COURT ADMINISTRATION, EITHER

ACTUAL OR REASONABLY-FORESEEABLE ........ 18

Conclusion ......................................... 30

Table of Cases:

Battle v. Mulholland, 439 F.2d 321 (5th Cir. 1971)... 18,25

Brooks v. Auburn University, 412 F.2d 1171

(5th Cir. 1969) 10

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia, 377U.S. 1, 5(1964) 6

Hobbs v. Thompson, 448 F.2d 456, 474 (5th Cir. 1971). 13

Page

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177, 181 <4th Cir.1966).. 22

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ............... 5,6,14

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S.563(1968)... 13,18,19,

20,23,28

Russo v. Central School District No.l, Towns of

Rush, etc. N.Y., 469 F.2d 623 (2nd Cir.1972)... 17

Shanley v. Northeast Ind. School Dist., Bexar

County, Tex., 462 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1972).... 9,10,29

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 L(1960)............. 17

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School

District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969) ................ 18,22,26,

28

United Mine Workers of America v. Illinois State

Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967).......... 6

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U.S. 364, 395 (1948) ......................... 18

Statute:

Code of Alabama, Tit. 13 §361 ...................... 27

ii

* *

The assistance of Daphne McFarlane in the preparation

of this Brief is gratefully acknowledged.

iii

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Fifth Circuit

No. 73'

C.D. (Denny) ABBOTT,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v-

WILLIAM F. THETFORD, individually and

in his official capacity as Judge of

the Family Court of Montgomery County, Alabama,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District Court For

The Middle District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE ON APPEAL

Interest of the Amicus

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. has

been the principal legal arm of the civil rights movement in this

country for many years. it has vrorked to establish the constitu

tional rights of black people to equality in education, employment,

voting, municipal services and public accommodations as well as to

equal justice under law. But the legal precedents that have been

set represent only the culmination of the long struggle by black

people to assert and secure recognition of their rights, as well

as the beginning of the equally arduous task of enforcing these

rights. This is a process which depends primarily upon fearless

and determined people who are willing to place their lives and

their livelihoods on the line to protest racial discrimination

and injustice. Such people are the prime movers of peaceful social

change and they are the only ones who can make the legal promise of

equality into a reality.

Because of its recognition of the importance of such

peaceful protest as a vehicle for social change, the Fund has

represented civil rights demonstrators from the early days of the

Montgomery bus boycott, as well as teachers and other government

employees who have been fired as a result of their civil rights

activity. The holding of the lower court, which upholds the dis

missal of Denny Abbott, a juvenile court probation officer, by

Judge Thetford, his employer, for filing a civil rights lawsuit in

violation of the judge's oral instruction, represents a serious

impairment of the right of government employees to pursue through

litigation or any other form of First Amendment expression the

lawful objectives of equality of treatment by all government for

black people in this country.

The Fund has an interest in this case for an additional

reason. Within the past year the Fund has started a juvenile

justice project, one purpose of which is to pursue equality of

treatment for black children in the juvenile justice and child

welfare systems. The Fund has joined in the federal civil rights

2

action filed by Denny Abbott on behalf of black neglected children

in Alabama, because the Fund believes that that lawsuit raises

novel and significant issues concerning the obligation of the

State to provide equal treatment to black neglected children, as

well as the obligation of the State to provide adequate treatment

to neglected children of all races.

The Fund believes that the lower court has seriously under

rated the magnitude of the constitutional rights which Denny Abbott

has exercised in filing a civil rights action as "next friend" for

black children. The Fund also believes that the lower court has

sanctioned governmental action which represents a shocking invasion

of the First Amendment rights of government employees, including

the right to peacefully protest racial discrimination. It is for

this reason that the Fund joins the plaintiff-appellant in urging

this Court to reverse the decision of the court below and to remand

the case to the district court with directions to grant the plaintiff-

appellant's prayer for relief.

Argument

I. IN FILING A FEDERAL LAWSUIT ON BEHALF OFTHE RIGHT OF BLACK NEGLECTED CHILDREN TO

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAW, DENNY ABBOTT

WAS EXERCISING HIS FIRST AMENDMENT FREE

DOMS OF SPEECH, PETITION AND ASSEMBLY

The Court below concluded its opinion by finding "that Mr.

Abbott exercised his rights of free speech, if not his right to

access to the courts," in filing a federal lawsuit on behalf of

the right of black neglected children to equal opportunity.(R.683)

3

This is the only place in its entire opinion that the court ex

pressed any assurance that Denny Abbott exercised an̂ . constitutional

rights in filing the lawsuit. Except for this one reference to

Mr. Abbott's right to free speech, the court below consistently

characterized the interest of Mr. Abbott which must be weighed

against the interest of the State as his employer in determining

the constitutionality of Abbott's discharge as "the rights of Plain

tiff to file a suit for others not then within his court's juris

diction and without any proof that others were not available to

file such a suit."(R.682; see also, R.674-75, 676). The court

expressed uncertainty concerning whether the "right to file a suit

for others" is constitutionally protected by raising and leaving

unanswered the question whether the Constitution guarantees access

to the courts " . . . for the purpose of righting wrongs for persons

other than the person seeking to assert the right." (R.674)

The court below seriously underrated the constitutional

magnitude of the interests of Denny Abbott which it was required

to weigh against the interest of the State as his employer. But

not only did the court fail to appreciate the constitutional

magnitude of the rights exercised by Mr. Abbott in filing a lawsuit

on behalf of black neglected children, but also the court clearly

concluded that it was not at all important that Mr. Abbott exercise

these rights In its opinion the court suggests that Mr. Abbott

could have substituted "any other adult" to appear as "next friend"

on behalf of the black children Mr. Abbott seeks to assist and that

Mr. Abbott could have thereby avoided a confrontation with his

4

employer, Judge Thetford, resulting in his discharge. The court

erroneously equates filing a lawsuit as "next friend" on behalf of

a child, whereby the "next friend" assumes a responsibility to pro

tect the best interest of that child, with lending "nominal" support

to a lawsuit or allowing one's name to be used in civil rights

litigation (R.675). Happily, Denny Abbott takes his responsibility

for children much more seriously than the lower court would have

yhim do.

The lower court also failed to understand that in filing

the suit on behalf of three black neglected children, Denny Abbott

not only was doing what he believes is in the best interest of those

children (R.343) but also was pursuing through litigation broader

objectives which have been characterized by the Supreme Court as

"a form of political expression": "the lawful objectives of equality

of treatment by all government, federal, state and local, for the

members of the Negro community in this country." N.A.A.C.P v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 429 (1963). (R.85, 121, 404, 411, 419). The undis

puted evidence in this case is that on many occasions Denny Abbott

expressed his concern over the lack of facilities for the placement

1/ Denny Abbott believes that his probation department has a duty "to work in the interest of all children that come into our

contact and we have knowledge of." (R.384). He initially

decided to file a civil rights lawsuit against the state

welfare department and several segregated group homes for

children on behalf of a fourteen year old black boy who had

been in the state training school since he was ten (in viola

tion of state law) because he had nowhere else to live.

Abbott first met the boy at the Montgomery Youth Aid facility

where Abbott is employed and, through contacts with various

administrators including the Deputy Director of the state

welfare department, endeavored unsuccessfully to find a

suitable placement for the boy. (R.84-87, 331, 398, 409, 415)

5

of black children adjudicated neglected or dependent by the juvenile

court. (R.372, 413). There can be no question that in filing a

lawsuit on behalf of the right of black children to equal oppor

tunity Denny Abbott was exercising his constitutionally protected

freedoms of speech, petition and assembly. The Supreme Court has

on three separate occasions in recent years affirmed " . . . that

the First Amendment's guarantees of free speech, petition and

assembly give [individuals] the right to gather together for the

lawful purpose of helping and advising one another in asserting

[ their] rights . . . " Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia,

377 U.S. 1, 5 (1964); In accord. United Mine Workers of America v.

Illinois State Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967); N.A.A.C.P. v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).

The First Amendment freedoms of speech, assembly and

petition which Denny Abbott exercised in filing a lawsuit to achieve

equality of treatment for black children have been described by the

Supreme Court as "delicate and vulnerable, as well as supremely

precious in our society." N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at

433. But in striking a balance between the interests of Denny

Abbott in exercising his constitutional rights and the interests

of the State as his employer, it is not these supremely precious

rights that the court placed in the scale but rather the right "to

file a suit for others not then within his court's jurisdiction

and without any proof that others were not available to file such

a suit." (R.682). After striking the balance and concluding that

"Abbott's rights pale in comparison"[R.683] the court then summarily

6

acknowledged that Abbott had exercised his constitutional right of

free speech- This belated reference to Abbott's freedom of speech

cannot cure the serious error that the court committed by greatly

underestimating the constitutional magnitude of the rights Denny

Abbott is exercising.

II. JUDGE THETFORD'S ORAL INSTRUCTION PROHIBITING

ALL JUVENILE COURT STAFF FROM FILING LAWSUITS,

WITH POSSIBLE EXCEPTIONS, IS FACIALLY UNCON

STITUTIONAL AS BOTH VAGUE AND OVERBROAD

The undisputed evidence is that Judge Thetford's sole

ground for firing Denny Abbott was Abbott's "wilful and deliberate"

2/disobedience of Thetford's oral instruction. This was the sole

ground stated in the letter dated November 22, 1972, that informed

Denny Abbott that he was discharged immediately (R.501-502), the sole

ground stated in the personnel record notice (R.503), and the sole

ground stated by Judge Thetford at the hearing on a motion for pre

liminary injunction and at the trial (R.57, 511-512). In view of

the undisputed evidence, the court below erroneously refused to

determine the facial constitutionality of Judge Thetford's oral

2/ At the trial, counsel for Judge Thetford stated as grounds

for an objection to the question whether Judge Thetford agreed

with the relief sought in the suit filed on behalf of black

neglected children, that "Consistently throughout this trial

Mr. Mandell has tried to make the firing related to the filing

of the lawsuit. I understand that theory. But the facts and

the evidence indicates without any dispute that the judge

fired Mr. Abbott because he violated a direct order." The

objection was sustained. (R.557)At the beginning of the trial, the court ruled that evidence

concerning the reputation of Mr. Abbott is irrelevant and would

not be admitted (R.255). The court also ruled evidence concerning the competency of Mr. Abbott inadmissible as immaterial

stating: "I understand that there is no contention Mr. Abbott

is not competent in this case."(R.259)

7

instruction, although this claim was clearly raised in the com

plaint (R.4-5) and was pressed throughout the trial (see, e.g.

3/R.391-393).

3/ The following colloquy occurred between the court and Abbott’s

counsel at the trial:

MR. MANDELL: . . . I think one of our grounds I allege that

the order is overbroad. It includes lawsuits that may be

justifiable.THE COURT: You haven't got such a lawsuit. If the order

were overbroad there are two answers. In the first place

you haven't got a lawsuit like that. You knew and he knew

that this is the sort of lawsuit, the very sort of lawsuit

that this order was written for. And he can't very well take

the position that this rule would have prevented me from

suing my wife for a divorce when he wasn't trying to sue

his wife for divorce. He brought a suit that was completely

related — and this may be an issue in the case, but this is

the contention — completely related to the function of the

court.

X X X

MR. MANDELL: . . . But the thing is if an order is overbroad

you have a right to challenge that overbreadth even if your

case is being unconstitutionally abridged.

THE COURT: Well, I don't think you do because you got to

show that you have a standing to challenge it. And yourstanding would be limited to the factual situation in which

you find yourself. Now, he could have gone into the state

proceeding. There is a state proceeding provided by statute,

as I read the law, under which he could have challenged this

situation when the rule first came out. But he saw fit notto do that. He waited and he deliberately violated the rule

and he deliberately filed the suit knowing that it was a

violation of the rule. According to the theory of defense,

as I understand it, he knew that this was clearly exactly the

sort of thing that Judge Thetford did intend to prohibit.

X X X

MR. MANDELL: Could I give you the case that holds that he

has a right to raise a question that is broader than the

particular case?

THE COURT: Yes. Do you have it?

MR. MANDELL: NAACP versus Button case. (R.391-393)

8

Under the principles set out by this Court in Shanley v .

Northeast Ind. Sch. Dist., Bexar County, Tex.. 462 F.2d 960 (5th

Cir. 1972), a facial approach is required in this case. "Especially

if the regulation is the sole rationale for punishment, the regula

tion must have a rationale constitutionally sufficient on its face."

Id., 462 F.2d at 975. Judge Thetford's application of his oral

instruction to prohibit and punish Denny Abbott's exercise of his

First Amendment freedoms and in addition Judge Thetford's con

struction of his instruction revealed in his testimony in this case

should convince this Court that a facial approach is compelled.

The circumstances under which Judge Thetford issued his

oral instruction are described in the Findings of Fact:

Judge Thetford, upon being informed in October, 1972,

that Chief Probation Officer Abbott was spending con

siderable time in the office of a lawyer known to be

interested in civil rights matters and suspecting that

he proposed to file another lawsuit, called together

three persons. Miss Goodwin, Mr. Franklin and Mr. Abbott, as department heads of court personnel, and issued an

order directing that no suit, with possibly some ex

ceptions, be filed by court personnel. While recollec

tions are in conflict as to the conditions of the pro

hibition, some of the witnesses testified that the

prohibition involved only suits which might involve

the operation of the Circuit Court and excepted those

suits wherein the Judge1s previous knowledge and consent was secured. (R.666-667).

This court need not resolve the conflict in recollections

as to the conditions of the prohibition in order to review the con

stitutionality of the oral instruction, because the oral instruction

even as recollected by Judge Thetford cannot pass the constitutional

tests required by the First Amendment.

9

According to Judge Thetford's recollection, he told his

supervisors "that I wanted no suit filed by any member of our staff

which would affect the work of the court without my knowledge and

approval" (R.495); he also prohibited his staff from assisting in

the filing of any lawsuit. (R.53, 538).

The need to speculate at large concerning the possible

implications of this oral instruction has been eliminated by Judge

Thetford's testimony in this case. That testimony, along with

Judge Thetford's reaction to Denny Abbott's exercise of his First

Amendment freedoms of speech, petition and assembly, confirms the

"worst fears regarding the variations of interpretation that could

pervert the regulation." Shanley v. Northeast Ind. Sch. Dist., Bexar

County, Tex., supra, 462 F.2d at 976. Judge Thetford's testimony

affirms that he intends to exercise an unconstitutional prior res

traint on his employees' exercise of their First Amendment freedoms,

see, e.g., Brooks v. Auburn University, 412 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.1969);

that his interpretation of his instruction sweeps protected activity

*wholly unrelated to the sound administration of the juvenile court;

that the language of the instruction is such that reasonable men

can differ and should differ substantially as to its meaning; and

finally that he does not restrict his interference with his employees'

First Amendment freedoms to lawsuits which interfere in a material

and substantial way with the proper administration of the juvenile

court:

Q. Now, suppose a member of your staff had contributed

money which would be used to assist in the frame of the

cost of the filing of a lawsuit which would affect Youth Aid Facilities?

10

A. Knowing my staff I doubt if they have it. My

thinking had not gone that far. I mean I wasn't being technical with them. I was simply—

x x

Q. How about making a speech to some group or civic

club with regard to the need of filing a lawsuit?

A. I had not thought of that possibility.

Q. Would that be included within the scope of your oral directive?

A. Well, as I say, I have never considered that possibility. I don't know.

Q. Suppose a member of your staff on his own time or

on her own time interviewed potential parties or witnesses?

A. To a suit that was going to be filed that would

affect my court? I think that would have been prohibited

by my order. I think that would have been within the purview of my order. Lets put it that way.

Q. How about writing a letter to a newspaper magazine

urging someone to file a lawsuit and expressing a need for such filing?

A. i would think that under the wording of my statute I should have been notified.

MR. STEWARD: Lets correct the words statute. Your instructions?

A. My instructions. (PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72,21-23)

x x

Q- . . . I would like for you to define, if you would

of the term affecting the operations of the court . . .

A. i think it means what it says.

x x

Q. I would appreciate it if you would define as best you can what you mean by that term.

A . In a lawsuit that would hamper or hinder any of my work as Judge of Juvenile Court.

x x

Q. Does it mean having any effect on the juvenile court

or having, as you said, would hinder or hamper you. Suppose

it had a positive effect on your job performance?

11

A. No. I expected to be notified of anything— well,

yes. I think anything that— I think you are getting

the picture. Anything that wDuld affect ray court, I

want to know about it.

A. Now—

A. Good, bad, or indifferent. That is not to say I

wouldn't have approved it if I thought it would help it.

(PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pg.24)

x x

Q. How about a lawsuit of a female probation officer

who alleging sex discrimination at the youth aid facility?

Your answer?

A. I had not contemplated that in my order, but it seems

that would affect our operation.

Q. It is not?

A. It would not affect our operation because we have

no sexual discrimination out there. (PI. Ex.4,12/20/72,

pg.25)

In response to the question whether a suit by a black staff

member charging racial discrimination in employment would fall within

the scope of the instruction, Judge Thetford replied:

A. I had certainly never thought about that. That

was not the kind of lawsuit I had in mind.

Q. Well, I am asking you why that would not affect

the operations of your court?

A. I don't think it would.

Q. Well, I am asking you why not?

A. Because I think they could win it and I don't think—

I just never have thought about it. I mean you are asking

questions now that never remotely occurred to me.

Q. Well, would not a lawsuit like that affect the

operations of your court?

A. I don't know whether it would or not. (PI.Ex.2,12/20/72,

pg.27)

x x

12

Q. Suppose one of your black staff members filed a

suit, as was recently filed before the Supreme Court, to integrate (sic.) the Kiwanis Club or the Moose or

the Elks or one of those similar clubs?

A. Well, I would have thought that if they had filed

a suit to integrate (sic.) the Kiwanis Club when I was

there asking for a $10 0 ,0 0 0 to build a home, yes, I

would have thought it would have affected the operation

of my court. The Moose Club— I don't know what the

Moose Club is and I don't know anybody that belongs to it.

Q. Well, lets say a female employee suing the Junior League— a black female— I don't know if you have any,

but lets assume that you had a black female probation officer

suing the Junior League.

A. Yes, I would have thought that would have adversely

affected my court and the project of what I was planning

for the court.

Q. And that you would not then have allowed them to file

that lawsuit?

A. No. Not as long as I was trying to get them to sponsor

a project. (PI.Ex.4, 12/20/72, pp.49-50).

There can be no question that the oral instruction as con

strued by Judge Thetford fails to meet the tests of constitutional

exactness required by the First Amendment. This Court has held

that in light of Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968)

and related cases, governmental regulations of the political activities

of public employees must be tested by traditional overbreadth prin

ciples. Hobbs v. Thompson, 448 F.2d 456, 474 (5th Cir. 1971). This

Court recognized in Hobbs that "the government should be able to

regulate activities which directly interfere with the proper per

formance of its employee's duties," but cautioned that restrictions

upon First Amendment freedoms "should not lightly be imposed", 448

F.2d at 470:

13

. . . a blanket prohibition upon political activity,

not precisely confined to remedy specific evils, would

deal a serious blow to the effective functioning of

our democracy. In this area, the overbreadth doctrine

plays an important role, for it requires the legislature

to focus narrowly on the particular evils it wishes to

combat when speech is at stake. 448 F.2d at 471.

Judge Thetford's instruction evidences no narrow focus or precision

of regulation whatsoever. It is "a vague and broad [rule which]

lends itself to selective enforcement against unpopular causes,"

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 435, and Judge Thetford's

testimony leaves no doubt that he intends to enforce his instruction

selectively. In addition, there is substantial evidence in this

case that the very purpose of the instruction was "selective enforce

ment" against causes unpopular with Judge Thetford. Judge Thetford's

oral instruction does not reflect the thoughtful attempt of an

administrator to regulate activities of his employees which sub

stantially and materially interfere with the sound administration

of the juvenile court or with the proper performance of their duties,

but rather reflects his personal reaction to the vigorous advocacy

of Denny Abbott on behalf of children.

Judge Thetford readily admits that the advocacy of Denny

Abbott prompted him to issue his oral instruction:

Q. And would you please state again in detail why you

felt at this time it was necessary to formulate such a

rule and directive?

A. I didn't want any lawsuit filed which would hurt

the work of my court.

Q. Now, why— my point is, at this time it had been

almost three years after Mr. Abbott had filed his initial

lawsuit, what prompted you at this particular time?

14

A. Because someone out at the court, and I am unable

to say who it was because I don't remember, telling me

Mr. Abbott was spending a lot of time in your office.

Q. Now, Judge, isn't it a fact that some members of

your court, without going into who they are or what the

purposes were, have filed lawsuits in the past two years?

A. Oh, yes. (R.534)

Although Judge Thetford initially denied that the fact that Mr.

Abbott was "going to a civil rights lawyer" affected his thinking,

he then testified:

Q. In other words, if you had seen Mr. Abbott in any

attorney's office you would have issued this directive?

A. No.

Q. Why wouldn't you issue it if he went into any attorney"s office?

A. Well, I think I know the lawyers in Montgomery.

Q. Why then — (interrupted)

A. The type of litigation they handle.

Q. So, it does have to bear on the type of litigation I

handle, is that correct?

A. No. Really, I can't honestly say. (R.535)

A reasonable inference based upon this testimony is that Judge

Thetford's sole purpose in issuing the oral directive was to prevent

Denny Abbott from filing another civil rights lawsuit. Judge Thetford

4/ In January, 1969 Denny Abbott brought a suit as "next friend"

on behalf of "indigent, scholastically retarded Negro children"

who v/ere confined at the Montgomery County detention center

awaiting admission to the state training school which had

refused to accept them due to overcrowding. The complaint

charged that the conditions of confinement at the detention

center and at the state training school constituted cruel and.

unusual punishment. (PI. Ex.8 , 12/20/72).

15

admitted that, had Denny Abbott complied with the oral instruction

(as recollected by Judge Thetford), Judge Thetford would not have

approved Abbott's filing the lawsuit on behalf of black neglected

children (R.262) Judge Thetford also admitted that he does not

think that the children's homes sued by Abbott should be forced to

integrate by a federal lawsuit (PI. Ex 4 12/20/72 pg 41)

The conclusion that the sole purpose of the oral instruction

was selective enforcement against Denny Abbott's advocacy is also

supported by the manner in which Judge Thetford issued the instruc

tion. Judge Thetford explained that he did not issue his oral

instruction to all of his court employees but only to the employees

at the juvenile court because "I had never had the problem before with

any of my employees in any other court." (PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pp.31-32)

He issued an instruction which substantially impairs the First

Amendment freedoms of his juvenile court staff and never bothered

to write it down because "I didn't expect to meet it in federal

court." (R.495). Because of Judge Thetford's failure to write

down the instruction, "recollections are in conflict as to the

conditions of the prohibition." (R.667). He admits that he "wasn't

being technical" (PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pg.21) and that he never

considered the scope of his instruction (PI.Ex.4, 12/20/72, pp.21-23).

Judge Thetford did not succeed in deterring the exercise

of Denny Abbott's First Amendment rights. But the danger is real

that in xssuing an oral instruction susceptible of sweeping and

improper application and then firing the Chief Probation Officer

for violating that instruction, Judge Thetford has deterred the

16

exercise by the remainder of his juvenile court staff of their most

5/precious freedoms. The fact that this instruction has been issued

by a Circuit Court judge can only magnify its inhibitory impact.

It is difficult to conceive of a more compelling case for a declara

tion of facial unconstitutionality.

Should this court declare Judge Thetford's oral instruction

facially unconstitutional, then Denny Abbott's discharge for exer

cising his First Amendment freedoms in violation of that instruction

cannot stand. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ; Russo v.

Central School District No.l, Towns of Rush, etc., N.Y., 469 F.2d

623 (2nd Cir., 1972)

5/ The Judge's reaction to the lawsuit filed by Denny Abbott in

1969 against the state training school and the county detention

center has also undoubtedly had an inhibitory impact on the

exercise by his employees of their First Amendment rights. The

Judge's reaction to the lawsuit was to have a bill introduced

in the legislature to have Abbott's position removed from the

merit system and placed at his discretion. (R.49-51, 270). At

the trial Judge Thetford explained why he feels he has closer

control Over his employees who are excluded from the merit

system: "Because if they don't do what I tell them to do then they know their job is in jeopardy without any if's, and's, or

but's."(R.271). When Denny Abbott spoke to the press about the bill to remove his position from the merit system, Judge Thetford

suspended him for 15 days, claiming that he had instructed Abbott

not to make any statements to the press relating to the lawsuit

because it was "damaging the image of the court." (R.43-44,266-269)

17

III. THE ORAL INSTRUCTION OF JUDGE THETFORD WAS UNCONSTITUTIONALLY APPLIED TO PROHIBIT AND

PUNISH PRESUMPTIVELY-PROTECTED FIRST AMEND

MENT EXPRESSION WITHOUT SUBSTANTIAL AND

MATERIAL DISRUPTION OF JUVENILE COURT ADMIN

ISTRATION, EITHER ACTUAL OR REASONABLY-

FORESEEABLE.

If this Court declines to take a facial approach to Judge

Thetford's oral instruction, this Court must then determine whether

under the circumstances of this case Judge Thetford has applied

that instruction unconstitutionally. This is the issue confronted

by the court below.

Judge Thetford may constitutionally "prohibit and punish"

Denny Abbott's exercise of his First Amendment freedoms of speech,

assembly and petition only if Abbott's exercise of those freedoms

has substantially and materially impaired his effectiveness as Chief

Probation Officer or substantially and materially interfered with

the administration of the juvenile court. Tinker v. Des Moines

Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969); Pickering

v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968); Battle v. Mulholland,

439 F.2d 321 (5th Cir., 1971).

A review of the entire evidence in this case will leave

this Court "with the definite and firm conviction" that the con

clusion of the lower court that Judge Thetford has sustained his

burden to show that Abbott's exercise of his First Amendment rights

has materially and substantially impaired his effectiveness as Chief

Probation Officer is a mistake. United States v. United States Gypsum

Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1948). The record in this case is barren

18

of any evidence that Denny Abbott's exercise of his First Amendment

freedoms of speech, assembly and petition by filing a lawsuit on

behalf of black neglected children has ". . .in any way either

impeded the . . . proper performance of his daily duties in the

[Youth Aid Facility] or . . . interfered with the regular operation

of the [juvenile court] generally.” Pickering v. Board of Education,

supra, 391 U.S. at 572-573.

Denny Abbott's primary responsibility as Chief Probation

Officer is to supervise the other probation officers (R.231). All

of the evidence in the record relating to the effect of Abbott's

appearance as "next friend" on behalf of black neglected children

in a federal lawsuit upon his ability to carry out this responsibility

indicates that his ability to supervise has in no way been impaired.

The evidence consists of the testimony of probation officers who are

under Abbott's supervision, the testimony of the other supervisors

at the Youth Aid Facility with whom Abbott has daily contact (R.72),

and the testimony of community agency representatives who have almost

daily contact with the Chief Probation Officer (R.36) including the

attendance supervisor and an attendance field social worker of the

county board of education, the director of social service for the

Montgomery Community Action Headquarters, and the assistant director

of the Montgomery Police Department Youth Aid Division.

Every probation officer who appeared testified that the

filing of the lawsuit on behalf of black neglected children by Abbott

has had no "adverse effect" upon his ability to perform his job and

that if Abbott were reinstated as Chief Probation he could continue

19

to have a close working relationship with Abbott (R.271, 278, 287).

Both supervisors who work with Abbott at the Youth Aid Facility

testified that they have had a good working relationship and could

continue to have a good working relationship with Abbott if he were

reinstated (R.573-74, 589). Each representative of a community

agency who appeared testified that the filing of the lawsuit has

had no "adverse effect" upon his working relationship with the

Youth Aid Facility and that he could continue his working relation

ship if Abbott were reinstated (R.259, 262, 265, 268).

Concerning Abbott's working relationship with Judge Thetford,

the undisputed evidence is that Judge Thetford is responsible for

the Domestic Relations Division of the Circuit Court as well as the

Juvenile Court (R.478), and is responsible for over 40 employees

at the Youth Aid Facility, including Denny Abbott and the six proba

tion officers he supervises (R.479). Abbott and Thetford work at

different locations and generally see each other no more than one

afternoon each week when Judge Thetford comes to the Youth Aid

Facility to conduct juvenile court hearings (R.73). They have no

other contact with each other except for infrequent staff meetings

(PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pg.15) or telephone conversations. (R.73)

Abbott's employment relationship with Judge Thetford is

" . . . not the kind of close working relationship for which it

can persuasively be claimed that person loyalty and confidence are

necessary to their proper functioning." Pickering v. Board of Education

supra, 391 U.S. at 570. This conclusion is supported by the un

disputed evidence that Judge Thetford lost his trust in Denny Abbott

20

as early as January, 1969, when Abbott filed the lawsuit against

a state training school and the county detention center (R.351)

and in spite of that they continued their working relationship for

almost four years to November, 1972 when Judge Thetford fired Denny

Abbott. Judge Thetford's testimony at the trial that Montgomery

County has one one the finest Youth Aid staffs in the State of

Alabama (R.564) indicates that trust is not a necessary element

of his working relationship with Denny Abbott.

The finding of the lower court that Abbott's exercise

of his First Amendment freedoms by filing the lawsuit on behalf

of black neglected children has destroyed the necessary trust

between Abbott and Judge Thetford and is evidence of a material

and substantial impairment of Abbott's effectiveness as Chief

Probation Officer is clearly erroneous. The undisputed evidence

is that although Judge Thetford lost trust in Denny Abbott as early

as 1969, they continued to work together with the result that

Montgomery County has one of the finest Youth Aid facilities in the

State.

The lower court's finding is erroneous for another reason.

Nowhere in the record of this case is there a suggestion by Judge

Thetford that the lack of trust between himself and Denny Abbott

was a ground for his discharge of Abbott. The only time Judge

Thetford even mentioned trust in connection with Abbott's activities

in 1972 was in response to a leading question at the trial (R.563).

The court below made its own independent finding that lack of trust

21

was a ground for Abbott's discharge and that finding is therefore

irrelevant. Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177, 181 (4th Cir. 1966).

As there is no evidence in the record that Abbott's

exercise of his First Amendment freedoms in any way impeded the

proper performance of his daily duties, his discharge can only be

sustained if his exercise of his constitutional rights substantially

and materially interfered with the regular operation of the juvenile

court generally, or if the record demonstrates facts "which might

reasonably have led [Judge Thetford] to forecast substantial dis

ruption of or material interference with [juvenile court] activities."

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, supra,

393 U.S. at 514.

Aside from its finding concerning the lack of trust between

Judge Thetford and Denny Abbott, the lower court based its conclusion

that Abbott's exercise of his First Amendment rights has "materially

and substantially impaired his usefulness as chief probation officer"

entirely on its finding that "the proposal for a new black children's

home before the United Appeal has been suspended until Abbott's suit

against Brantwood is decided." (R.683). This effect of Abbott's suit

upon a black children's home project is the only "adverse effect"

upon the juvenile court which Judge Thetford was able to describe

at. the trial (R.541) .

This "adverse effect" described by Judge Thetford and relied

upon by the court below does not constitute a substantial and material

interference with the regular operation of the juvenile court for

22

two reasons. First, the "adverse effect" was not upon the regular

operation of the juvenile court but was upon a civic project in

which Judge Thetford is participating to establish three homes for

"predominantly Negro children*1 (R.274-275) . Working with Judge

Thetford on the project are the Kiwanis Club, of which he is member

(PL. Ex.4 12/20/72, pg.46), the Junior League, the Jewish Ladies

Federation and the Alabama Montgomery Christian Ladies Organization

(R.524). Judge Thetford is a member of the steering committee of

the project along with a clergyman, a professor, a radio announcer

and others (R. 52 5)1 Although the purpose of this project is to

create a resource which can be utilized by the juvenile court and althoug

the Circuit Judge in charge of the juvenile court is actively involved

in the project, the project is not an operation of the juvenile court

nor is it closely related to the day-to-day operations of the juvenile

court. It is a cooperative, charitable project of a number of civic

organizations and as such is a matter of general public interest.

In relation to this project, Denny Abbott must be regarded as a member

of the general public. Pickering v. Board of Education, supra.

Second, even if this project were part of the regular

operation of the juvenile court, there is insufficient evidence in

the record that Abbott's filing of the lawsuit substantially and

materially interfered with this project. The only evidence relating

to this question is Judge Thetford's testimony. He testified at the

trial on January 14 and 15 that the project hopes to obtain the

support of the United Appeal, which presently supports Brantwood— one

of the segregated children's homes sued by Denny Abbott on behalf

23

of black children (R.526, 532). According to Judge Thetford,

Abbott's lawsuit represents a threat to the project because "if

Brantwood were integrated then there would be — or the general

consensus seems to be no need or possibly no need for an additional

children's home." (R.527). This "general consensus of opinion—

. . . that nothing could be done until after this suit was teminated

because if the suit was successful the United Appeal would not under

write it because it would be a duplication of effort"— emerged at

a meeting on January 4, 1973. Judge Thetford clarified this

testimony by adding that " . . . there were many opinions expressed

but that is what I got — the consensus."(R.526).

At his deposition on December 12, 1972 Judge Thetford had

no evidence but "simply a feeling" that Abbott's lawsuit might

jeopardize the "Negro home" project (PL.EX.4 12/20/72, pp.29,47).

At the hearing on December 20, Judge Thetford based his conclusion

that the lawsuit might adversely affect the project on "common

knowledge". (R.64).

The only evidence in the record that the lawsuit filed by

Abbott on behalf of black neglected children has interfered with

Judge Thetford's project is Judge Thetford's view of the "consensus"

at a meeting held less than two weeks before the trial. There is

no evidence that any representative of the United Appeal has taken

the position that the United Appeal may not make a substantial

commitment to the project until Abbott's lawsuit has been resolved

and may decline to support the project if Brantwood is integrated.

24

Nor is there any evidence that a representative of the United Appeal

was even at the meeting on January 4 where this "consensus" emerged.

"As to private citizens, it is exactly this type of restrictive

response, based on theoretical reactions by others in the actions

of the accused, which has long been condemned." Battle v. Mulholland

439 F.2d at 324.

Thus the only evidence presented by the defense of substantial

and material interference with the work of the juvenile court is

speculation about the reactions of others. But even if one takes as

the truth Judge Thetford's speculation about the reaction of the

United Appeal, these facts are not evidence of an interference with

the proper administration of the juvenile court. Judge Thetford

may characterize the effect of Abbott’s lawsuit on his project as

an "adverse effect" or "interference" but this Court is not bound

by Judge Thetford's labels. In fact Abbott's litigation does not

clash with Judge Thetford's project. On the contrary, the relief

sought in the lawsuit and the goal of Judge Thetford's project are

the same: the provision of adequate homes for black neglected children.

Judge Thetford's concern is not that Abbott's lawsuit in

any way obstructs the provision of adequate homes for black children

but rather that, if Abbott's litigation is successful, then the

bores for predominately Negro children" which Thetford's project

seeks to build may not be needed. In other words, if the existing

segregated homes are required to integrate, then the need to build

separate facilites for black children is eliminated.

25

Abbott's litigation may well have this effect on Judge

Thetford's project but whether one characterizes that effect as

beneficial or adverse depends upon one's political and social

philosophy. Judge Thetford does not believe that the segregated

homes in which he places children should be compelled to integrate

by a federal court (PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pg.41). As he stated at

the trial, "it is certainly my philosophy that you can do a lot more

with honey than you can with vinegar." (R.546). But Judge Thetford

cannot constitutionally impose his political and social philosophy

upon his employees by firing them when they file lawsuits opposed to

his philosophy and that is precisely what Judge Thetford has done in

this case. Aside from the elimination of the need for separate

homes for black children, Judge Thetford was not able to describe

any other "adverse effect" of Abbott's lawsuit upon his court at

the trial:

Q. Other than the fact that you mentioned there

might be a duplication of efforts, what other adverse effect to your knowledge had the filing of that lawsuit

had on your court?

A. As of now, none; that I know of. (R.541).

Thus this Court is confronted with a record which contains no evidence

that Abbott's exercise of his constitutional rights has in any way

interfered with the proper administration of the juvenile court.

The record is also devoid of facts "which might reasonably

have led [Judge Thetford] to forecase substantial disruption of or

material interference with [juvenile court] activities." Tinker v.

Des Moines Independent Community School District, supra, 393 U.S.

26

at 514. Aside from the evidence already discussed, the only

other circumstances which arguably might have led Judge Thetford

to forecast material and substantial interference with juvenile court

administration relate to the working relationship between the juvenile

court and the defendants in the lawsuit filed by Abbott on behalf of

black neglected children — the state child welfare department

(Department of Pensions and Securities) and the private group homes

for children.

Alabama law provides that Judge Thetford may commit a

neglected child to "any orphanage, institution, association or agency

approved by the State Department of Public Welfare " . . . which is

willing to receive such child" or may commit to the Department of

Pensions and Securities such neglected children as it is "equipped

to care for and agrees to receive". Code of Ala., Tit. 13 §361.

[emphasis added]. Because the State does not operate its own

group homes for children, the only resources presently available to

Judge Thetford for the placement of neglected children, aside from

foster parent placements, are the group homes sued by Denny Abbott.

Judge Thetford explained his belief that Abbott's lawsuit could

damage these resources at his depositon:

He filed suit abainst at least four of my resources

for the placement of children which may well result in

them shutting them down or them refusing to take any

more children from Montgomery because they can do it.

(PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72 pp. 27-28).

The record of this case is barren of any objective evidence to

support Judge Thetford's belief. Concerning the working relation

ship between the Department of Pensions and Security and the juvenile

27

court, Judge Thetford testified that his Youth Aid staff has

continued to work with that Department on a daily basis since

the filing of Abbott's lawsuit (R.546) and yet he could describe

no adverse effect of the filing of the lawsuit on that relationship

(R.541). The only other evidence relating to the Department of

Pensions and Security is the testimony of two probation officers

that the probation staff has continued to enjoy a good working

relationship with that Department since the filing of the suit

(R.270, 275-276).

The only evidence in support of Judge Thetford's belief

that the filing of the lawsuit would harm relations between his

court and the private group homes is the Judge's testimony that the

administrators of two homes " . . . have told me they figured this

suit was going to badly cripple them as far as donations were con

cerned." (R.65, 548). His belief that the homes would retaliate

against his court by refusing to accept placements is contradicted

by evidence that since the filing of the suit by Abbott, Brantwood

Home has accepted the placement of a child from Judge Thetford's

court (R.653) and no other placements have been attempted (R.546-547)

The evidence is also undisputed that the total number of placements

made to the home*annually by Judge Thetford is small. In 1972,

Judge Thetford made a total of nine placements to the six homes

sued by Abbott (7 to Brantwood, 1 to Baptist Home, and 1 to the

Sheriffs’ Boys Ranch)(R.547).

When the Tinker/Pickering standards are applied to this case

"it is beyond serious question that the activity punished here does

28

not even approach the 'material and substantial' disruption that

must accompany an exercise of expression, either in fact or in

reasonable forecast." Shanley v. Northeast Ind. Sch. Dist., Bexar

County, Tex., supra, 462 F.2d at 970. In Shanley, this court

stated the guidelines applicable to the "reasonable forecast of

disruption" standard:

We emphasize, however, that there must be demonstrable

factors that would give rise to any reasonable forecast

by the school administration of "substantial and material"

disruption of school activities before expression may be

constitutionally restrained. While this court has great

respect for the intuitive abilities of administrators,

such paramount freedoms as speech and expression cannot

be stifled on the sole ground of intuition . . .[the administrators'] viewpoint [must be] substantiated by

some objective evidence to support a reasonable "forecast"

of disruption or by actual disruption. [emphasis added]

The entire record of this case contains no "demonstrable factors"

or "objective evidence" to support a reasonable forecast by Judge

Thetford of interference either with the proper performance of

Abbott's duties or with the regular operation of the juvenile court.

When Judge Thetford fired Denny Abbott, he had "simply a feeling"

that the lawsuit filed by Abbott would damage the relations between

his court and the children's homes and would harm his "predominantly

Negro" children's home project (PI. Ex.4, 12/20/72, pp.29, 477.

Under the Shanley guidelines, Judge Thetford's forecast of inter

ference must be based on more than a feeling.

A review of the entire evidence in this case will leave

this Court with the firm and definite conviction that the filing

of a federal suit by Denny Abbott on behalf of black neglected

children has in no way impeded the proper performance of his daily

29

duties, has in no way interfered with his working relationships,

and has in no way interfered with the regular operation of the

juvenile court. In support of Judge Thetford's fear that the

lawsuit would interfere with his "predominantly Negro" home project —

which is not even part of the regular operation of the juvenile

court — the defense presented only the Judge's speculation that

the United Appeal may determine that the "predominantly Negro"

homes are not needed. In support of Judge Thetford's fear that

the lawsuit would harm the relations of his court with the Department

of Pensions and Securities and the children's homes, the defense

presented only the Judge's testimony that the administrators of two

children's homes have told him that integration of the homes may

affect donations. The defense has not met its burden to show

substantial and material interference, either actual or reasonably-

foreseeable, with the performance of Abbott’s employment duties or

with the administration of the juvenile court, and therefore the

oral instruction of Judge Thetford has been unconstitutionally

applied to prohibit and punish Abbott's exercise of his First

Amendment freedoms.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the court below

should be reversed and this case remanded with directions to grant

30

the relief requested by plaintiff-appellant.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III ANN WAGNER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

\

31