Marshall v Holmes Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 8, 1974

33 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marshall v Holmes Brief of Appellants, 1974. cc456814-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/759e9cf2-f6d3-4436-bf6c-00422d85d18b/marshall-v-holmes-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

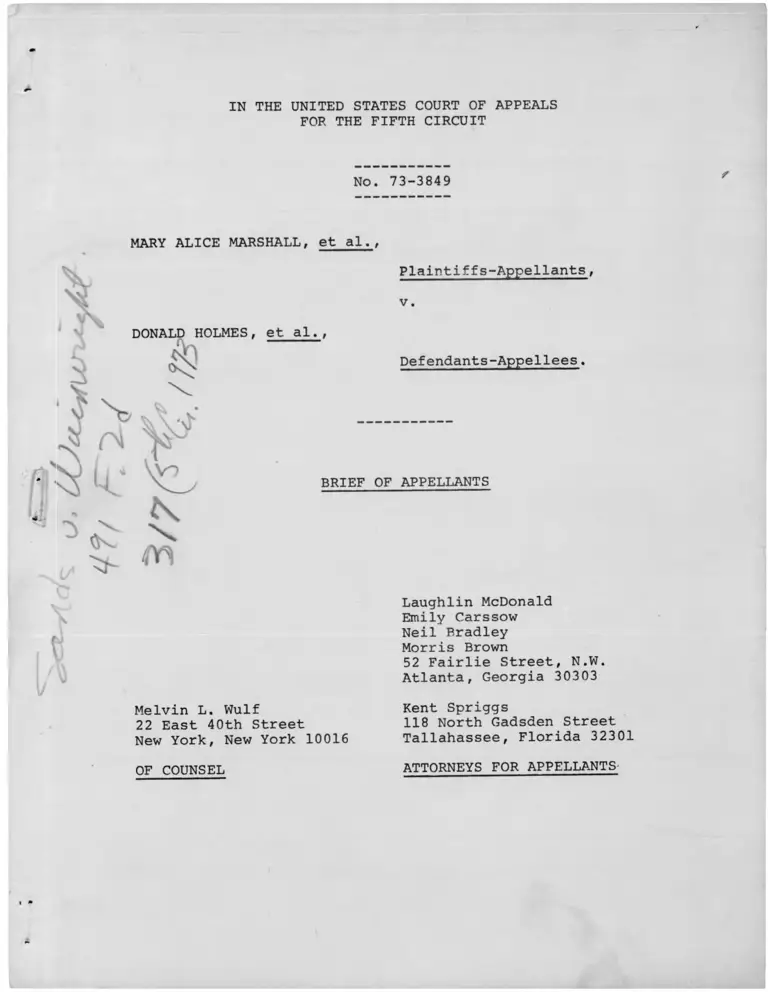

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3849

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, et al.,

Laughlin McDonald

Emily Carssow

Neil Bradley

Morris Brown

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Melvin L. Wulf

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

OF COUNSEL

Kent Spriggs

118 North Gadsden Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-3849

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

DONALD HOLMES, et al.,

Pefendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have caused two copies of the Brief of

Appellants to be served on the -Honor-ab-le -Reber^ETTevin,

Attorney--GenerarL^—Th-e--Capitol Tallahassee , Florida

32301,-by placing them In an envelops.,— aix. mail postage

prepaid , and depositing them in the United States mail.

Done this 8t’n day of January, 1974.

s/Neil Bradley

Neil Bradley

No. 73-3849

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

DONALD HOLMES, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

The undersigned, counsel of record for appellants, certi

fies that the following listed parties have an interest in the

outcome of this case. These representations are made in order

that the judges of this Court may evaluate possible disquali

fications or recusal pursuant to local Rule 13(a).

1. Mary Alice Marshall

2. William Hunt

3. Fannie Mae Jamison

4. Willie Mae Allen

5. Rosa Lee Brown

6. Joe E. Scott

7. Andrew Lee

8, Will, lam F . Gavin

9. J. Willard Smith

10. Marshall D . Cannon

The interest of each of the above is that he or she is a party.

Attorney for Appellants

i

INDEX

Page

Certificate of Counsel

Issues Presented -

I The district court erred in failing to

convene a three-judge court to adjudicate

the constitutionality of the mother's

exemption provision of the Florida jury

law: the exemption is invalid on its face

II The women's exemption renders an uncon

stitutional result in Levy County; the

district court had jurisdiction and should

have decided the question in favor of

the plaintiffs........ \ ...................

Ill The defendants have discriminated against

black citizens as a class in the selection

of persons for the jury l i s t .............

V

Statement of theXase^..............................

hi ^

Point I The district court erred in

failing to convene a three-judge

court to adjudicate the constitu

tionality of the mother's exemption

provision of the Florida jury law:

the exemption is invalid on its facfe.

Point II The women's exemption renders an un

constitutional result in Levy County;

the district court had jurisdiction

and should have decided the question

in favor of the plaintiffs . , . . .

Point III The defendants have discriminated

against black citizens as a class in

the selection of persons for the jury

11s t ................. ..

/

. 1

1

1

1

3

16

20

Conclusion 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1971) . . .

Astro Cinema Corp. v. Mackell, 42 2 F. 2d

293 (2nd Cir. 1970) ..........................

Atkins v. Charlotte, 296 F. Supp. 1068 (D.N.C.

1969) .........................................

• 3 G K 2 V -

Broadway v, Culpepper, 439 F. 2d 1253 (5th

--Cir. 1971) .....................................

17

19

5

't t

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966) . .

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) .

Cleveland v. United States, 323 U.S. 329 (1945)

Data Processing Service v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150

(1969) ......................................... 4

DeKosenko v. Brandt, 63 Misc. 2e 895, 313 N.Y.S.

2d 827 (S. Ct. 1970) ..........................

Ford v. White, 430 F. 2d 251 (5th Cir. 1970) . .

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U. S. 677 (1973) .

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464 (1948) . . . .

Grimes v. United States, 391 F. 2d 709 (5th Cir.

1 9 6 8 ) ........................................... ..

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) . . .

Hall v. Garson, 430 F. 2d 430 (5th Cir. 1970). . .

Healy v. Edwards, 363 F. Supp. 1110 (E.D. La.

I U ( V I i t - r . __ - i rs / -» /-• a h v •*- \x ̂ « w / \ j ŝ uui. • • • • s • s 9 v # a 0

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ...........

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961) ...............

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F. 2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966) . .

iii

Mayhues Super Liquor Store v. Meiklejohn, 426

F. 2d 142 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ...................... 3

McGowan v. Maryland, 306 U.S. 420 (1961) . . . . 7

McMannaman v. United States, 327 F. 2d 21 (10th

Cir. 1 9 6 4 ) ........................................ 4, 5

Cases Cont'd Page

1 !

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala.

! 9 6 6 ) ........................................... 4, 10

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972)............. 6

Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246 (1941) . . 18

J ? /3/Xnl.lum v. Greene, 396 F. 2d 251 (5th Cir. 1968) . *-- 7~

Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971)............... 6, 13

Rorick v. Board of Commissioners, 307 U.S. 208(1939) 18

Rowe v. Peyton, 383 F. 2d 709 (4th Cir. 1967) . . 9

\D Smith v. Yeager, 4 65 F. 2d 272 (3rd Cir. 1972), 5

— / i/, H /$* ^ */f7 £ r-

Spencer v. Kugler, 454 F. 2d 839 (3rd Cir. 1972). 18

Stainback v. Mohock Ke Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368 (1949) 18

7, /Z'Turner v. Fouche, 396 U. S. 346 (1970)........... o\ /

a j ^ u - y/ )l, rtfs. c

United States v. Pentado, 463 F. 2d 355 (5th Cir.

1 9 7 2 ) ............................................. 5

White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966) . 5, 15

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 100 (1970) . . . 2$ ̂ __

Constitution of the United States

Fourteenth Amendment ............... ,

JLloxida Statutes § 4 0 . 0 1 ............

? ̂ 7 / 7 1 /” * ^28 U.S.C. §§' 2281 and 2284 ..........

N.J.S.A. § 93-1304(12) ...............

5

13

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No.. 73-3849

Summary Calendar*

MARY ALICE MARSHALL, ET AL.,

For themselves and For all

others similarly situated,

versus

Plaintiffs-Appc 1 iants ,

DONALD HOLMES, ET AL.,

Etc. , .

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Florida

( May 30 , 1974)

Before COLEMAN, DYER and RONEY, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

We affirm the judgment of the district court for the

reasons set forth in its adjudication 365 F.Supp. 613 . See

1/

Local Rule 21.

*Rule 18, 5 Cir., see Isbell Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizens Casualty

Company of New York, et al., 5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 409, Part I.

1J See NLRB v. Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, 5 Cir. 1970,

430 F .2d 966.

I

Page

Other Authorities

Anno. 15 L. Ed. 904, 918 (1966) . . . . . . . 17

Johnston and Knapp, Sex Discrimination by Law:

A Study in Judicial Perspectives, 46 N.Y.U.L.

Rev. 675 (1971)......................~T~7 . 11

Nagel and Weitzman, Women as Litigants, 23 Hast

ings L. J. 171 (1971)................... “ 4

U. S. Women's Bureau-Dept of Labor, Highlights of

Women's Employment and Education (1973) T . ̂ \ 14

V , $ ■ , M u s 'k a u

a'f ft.4 0 ^ - s s s , - 4 L - J ^ / > J * 1

L-Lzx.jL___ A s .t A-k - j

^ J t/ { K .

V

ISSUES PRESENTED

I. The district court erred in failing to convene a

three-judge court to adjudicate the constitutionality of

the mother's exemption provision of the Florida jury law:

the exemption is invalid on its face.

II. The women's exemption renders an unconstitutional

result in Levy County; the district court had jurisdiction

and should have decided the question in favor of the plaintiffs.

III. The defendants have discriminated against black

citizens as a class in the selection of persons for the jury

list.

-C-v*

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On January 13, 1972, a group of black men and women citi

zens filed the complaint, alleging that blacks and women were

underrepresented on the Levy County juries. The issues were

framed and the case tried on the amended domplaint. R. 61.

On April 20, 1973, plaintiffs moved to convene a three-judge

court for the purpose of adjudicating the constitutionality of

that portion of Florida Statutes § 40.01 which allows women

with children under 16 to opt out from jury service. R. 92.

The case was adjudicated on stipulated facts. R. 94-95,

100-02, 106-07. The court entered an Opinion-Order on Septem

ber 28, 1973, declining to convene a three-judge court and

resolving all issues in favor of the defendants. T. 108.

Judgment was entered that day. T. 120. The notice of appeal

was filed October 23, 1973, T. 121.

Because the facts were stipulated and have been reduced

to several stipulated pages, it will be more expeditious for

the Court to read those pages verbatim in the Appendix. R.

100-02 , 94-95 , 106-07.

-2-

POINT I

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO CONVENE A THREE-JUDGE COURT TO

ADJUDICATE THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF

THE MOTHER'S EXEMPTION PROVISION

OF THE FLORIDA JURY LAW:

THE EXEMPTION IS INVALID ON ITS FACE

Plaintiffs requested that a three-judge court be convened

as authorized by 28 U.S.C. §§ 2281 and 2284. R.'92. The sub

stantive test in determining the propriety of a three-judge

court is simple, although its application is not always so easy:

"unless the claim of validity/invalidity is insubstantial a

three-judge court is required." Mayhue1s Super Liquor Store,

Inc, v. Meiklejohn, 426 F .2d 142, 144 (5th Cir. 1970). In

light of recent Supreme Court decision dealing with discrimi

nation on the basis of sex, the contention that the Florida

Statute is a denial of equal protection to potential female

jurors is neither insubstantial nor without merit.

The right and obligation of female citizens to partici

pate in the administration of justice on the same basis as male

citizens is appropriately regarded as an essential accoutre

ment of the constitutional right to an impartial jury drawn

from all segments of the community. Carter v. Jury Commission,

396 U.S. 320, 330 (1970); cf. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S.

479 (1965). The right flows as a matter of equal protection to

women as potential jurors and litigants and to society as a whole

as a matter ot due process, helping to insure that the judicial

system functions to provide the fair trials that representative

juries promote. Carter, supra; Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972).

Without women as triers of fact, women litigants suffer a

-3-

demonstrable "injury in fact." Data Processing Service v.

Camp, 397 U.S. 150, 152 (1969). "The two sexes are not fungible;

a community made up exclusively of one is different from a community

composed of both." Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187, 193 (1946).

A female personal injury plaintiff, for example, is likely to

suffer a significant disadvantage from the absence of women on

her jury. Empirical studies indicate that male-dominated

juries, such as those which sit in Florida courts as a result of

the challenged jury selection provisions, award greater

damages to male than to female plaintiffs in civil cases, and

are likely to give male defendants lighter sentences than fe

male defendants in criminal cases. Nagel & Weitzman, "Women

as Litigants," 23 Hastings L.J. 171, 192-97 (1971).

Many of the jury discrimination cases appear to blend

"equal protection" and "due process" analysis without sharp

distinction between the two. See, e.g. , Labat v. Bennett, 3 65

F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966); Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp.

117 (M.D. Ala. 1966). Cf. Ford v. White, 430 F.2d 951 (5th

Cir. 1970); McMannaman v. United States, 327 F.2d 21 (10th

Cir. 1964). At base, the jury selection decisions appear to

rest on a formulation tailored to the special concerns entailed

in safeguarding lay participation in our system of justice in

a manner reflective of the larger community served.

In effect, courts have applied to the exclusion from jury

service of any "cognizable group or class of qualified citi

zens" the almost per se rule until recently reserved for dis

crimination against blacks. Grimes v. United States, 391 F . 2d

-4-

709 (5th Cir. I960); see also McMannaman, supra. The excluded

group, to be considered "cognizable," must represent simply a

"distinct class" in the community. In the seminal decision

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 478 (1954), the Supreme Court

stated:

Throughout our history differences in race and

color have defined easily identifiable groups

which have at times required the aid of the

courts in securing equal treatment under the

law. But community prejudices are not static,

and from time to time difference from the com

munity norm may define other groups which need

the same protections.

Significantly, the Court pointed out in Hernandez that "the

Fourteenth Amendment is not directed solely against discrimi

nation due to a 'two-class theory' — that is, based on dif

ferences between 'white' and 'Negro'." Moreover, more recent

.decisions have not required that excluded groups demonstrate

discrimination against them in the community. Groups labelled

"cognizable" include daily laborers, Labat v. Bennett, supra;

members of any "economic class," Smith v. Yeager, 465 F .2d 272

(3rd Cir. 1972); and non-alien Spanish-Americans, United States

v. Pentado, 463 F .2d 355 (5th Cir. 1972).

Recognizing that "the two sexes are not fungible; a com

munity made up exclusively of one is different from a community

composed of both," Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187, 193

(1946) , a number of courts have characterized women as a "cog

nizable group" for purposes of jury discrimination equal pro-

tPo-Hnn analysis. Spp. e .g . . Smith v. Yeager, supra; White v.

Crook, 251 F. Supp 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966). These courts have

held unconstitutional discrimination against women in jury

selection just as they have invalidated discrimination against

other groups. Most significantly, the Supreme Court itself

-5-

has indicated its approval of this approach. In Peters v.

Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 503 (1972), the Supreme Court stated:

When any large and identifiable segment of the

community is excluded from jury service, the

effect is to remove from the jury room quali

ties of human nature and varieties of human ex

perience, the range of which is unknown and

perhaps unknowable. It is not necessary to

assume that the excluded group will consistently

vote as a class in order to conclude . . . that

their exclusion deprives the jury of a perspec

tive on human events that may have unsuspected

importance in any case that may be presented.

A. The Challenged Florida Jury Selection Pro

visions Work an Invidious Discrimination.

With some notable exceptions, until the current decade,

courts employed a narrow scope of review for equal protection

challenges to legislation according different treatment to

women and men. No line drawn between the sexes, however sharp,

failed to survive constitutional assault. Gross generaliza

tions concerning woman's place in man's world were routinely

accepted as sufficient to justify discriminatory treatment.

See, e.g., Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464 (1948); Hoyt v.

Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961).

In 1971, a new direction was signalled by the Supreme

Court. In Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), the Court invali

dated an Idaho statute that gave a preference to men over wo

men for appointment as estate administrators. Explicitly re

pudiating one-eyed sex role thinking as a predicate tor legis

lative distinctions, the Reed opinion declared, "[the statute]

provides that different treatment be accorded to the applicants

on the basis of their sex: it thus establishes a classification

-6-

subject to scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause." 404

U.S. at 75. Recognizing that the governmental interest urged

to support the Idaho statute was "not without some legitimacy,"

404 U.S. at 76, the Court nonetheless found the legislation

constitutionally infirm because it provided "dissimilar treat

ment for men and women who are similarly situated." 404 U.S.

at 77.

Although the Reed opinion was laconic, it was apparent

that the Court had departed from the "traditional" equal pro

tection analysis familiar in review of social and economic

legislation. Sex-based distinctions were to be subject to

"scrutiny," a word until Reed typically reserved for race dis

crimination cases where the term was paired with a requirement

that the legislation meet a "compelling interest" standard.

"Traditional" equal protection rulings, by contrast, mandated

judicial tolerance of a legislative classification unless it

is "patently arbitrary." McGowan v. Maryland, 306 U.S. 420,

426 (1961).

On May 14, 1973, in Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677,

686, the Court made explicit the incurable flaw in governmental

schemes that accord different treatment to males and females

solely on the basis of their sex:

Since sex, like race and national origin, is an ̂ * X- —% l» 1 —. 1 — — .— * — .— “1 1 1 ’

xuUuu t.a i rr i s i i i ■ wr t i u i n tr# - --------- -------------------J. ~ J.

the accident of birth, the imposition of special

disabilities upon the members of a particular

sex because of their sex would seem to violate

the basic concept of our system that legal bur

dens should bear some relationship to individual

responsibility. . . . And what differentiates

sex from such non-suspect statuses as intelli

gence or physical disability, and aligns it with

-7-

the recognized suspect criteria, is that the

sex characteristic frequently bears no relation

to ability to perform or to contribute to so

ciety. As a result, statutory distinctions

between the sexes often have the effect of in

vidiously relegating the entire class of females

to inferior legal status without regard to the

actual capacities of its individual members.

Despite the obviously sweeping ramifications of .rejection of

this pervasive legislative pattern, the Court was unwilling to

perpetuate the distinction. The message of Frontiero is clear

persons similarly situated, whether male or female, must be

accorded even-handed treatment by the law. Legislative clas

sifications may legitimately take account of need or ability;

they may not be premised on unalterable sex characteristics

that bear no necessary relationship to an individual's need,

ability or life situation.

The plurality opinion in Frontiero, delivered by Justice

Brennan, declares with unmistakable clarity that classifica

tions based upon sex, like classifications based on race,

alienage or national origin, are inherently suspect and must

therefore be subject to close judicial scrutiny. While four

justices characterized sex classifications as "suspect," Jus

tice Stewart, concurring in the judgment, preferred to label

the distinction "invidious." All of the Justices, save the

lone dissenter, rejected "administrative convenience" as jus

tification for dissimilar treatment of men and women.

Frontiero concerned, as this case does, the assumption

that women are destined for the care of husbands, home and

children, men for participation in the world outside the home.

Law-sanctioned assumptions of this kind, that fail to account

-8-

for the substantial and dramatically increasing population of

women and men who do not organize their lives according to the

stereotype, have been relegated to the scrap heap by Frontiero.

Hoyt no longer impedes federal courts confronted with

jury selection practices that exclude or exempt women.

For the Supreme Court has rejected "minimal rationality"

equal protection analysis for legislation that establishes

sex-based classifications. Such classifications are now

recognized to be "suspect" or "invidious." Frontiero v .

Richardson, supra. Nor is this court required to wait until

the Supreme Court reconsiders and overrules Hoyt. In Healy

v. Edwards, 363 F. Supp. 1110 (E. D. La. 1973) (three-judge

court), declaring unconstitutional Louisiana's laws exempting

women from service on juries absent the filing of a written declaration

of desire to serve, the court acknowledged, quoting from Rowe

v. Peyton, 383 F. 2d 709, 714 (4th Cir. 1967), affirmed 391 U.S.

54 (1967), "there are occasional situations in which subsequent

Supreme Court opinions have so eroded an older case, without explicitly

overruling it, as to warrant a subordinate court in pursuing what

it conceives to be a clearly defined new lead from the Supreme

Court to a conclusion inconsistent with an older Supreme Court

case." Healy concluded that Hoyt was "yesterday's sterile precedent"

and considered it "no longer binding." 363 F. Supp, at 1117.

The court declared the provisions of law before it, which are

analogous to those involved here, unconstitutional in that they

were an "interference" with the right to a jury comprising a fair

cross section of the population in violation of due process and

denied women equal protection of the law.

-9-

B. Jury Selection Entails a Fundamental Right.

A three-judge court is mandated not only because of the

invidious discrimination that the statute works but also be

cause the case involves a question concerning a fundamental

right — the right to serve on a jury. The existence of a

right to be eligible for jury service cannot be disputed —

numerous decisions, in both actions by members of allegedly

excluded classes and actions by litigants alleging improper

indictment or trial, have plainly recognized it. These de

cisions classify jury service as a "badge of citizenship"

closely analogous to the vote. Carter v. Jury Commission, 396

U.S. 320, 330 (1969); Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117,

121 (M.D. Ala. 1966). While this right is not explicitly

guaranteed by the words of the Constitution, an implicit guar

antee may be identified, for the right to jury service is

appropriately viewed as an essential Sixth Amendment accoutre

ment, cf. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) , with

out which the right to trial by an impartial jury of one's

peers could not be secured.

C . The "Benign" Classification that Serves to

Keep Women m Their Place.

It might be argued by persons who overlook the harmful

effects of "special treatment" for women that the question of

-10-

whether a "suspect" or "invidious" classification, or a "fun

damental right" is involved in this case is irrelevant, at

least insofar as it concerns female plaintiffs as potential

jurors. For the nature of the classification, on surface in

spection, may not appear invidious -- women are afforded the

"special benefit" of not having to serve on juries. This su

perficial assessment may explain the Court's unwillingness in

Hoyt to consider classification of women in a context similar

to this as "suspect" — apparently, in the Court's view, Flo

rida women were being advantaged by that classification. But

absence of responsibility for jury service is hardly an un

mixed blessing. Jury duty, as noted above, cannot be charac

terized simply as a burden — it is a vital right, a "crucial

citizen responsibility," Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F .2d 1253

(5th Cir. 1971).

The automatic exemption from jury service which Florida

extends to women is an indicator of second class citizenship,

a reflection of the state's conception of women as a class

not capable of shouldering the same civic rights and respon

sibilities as men: "statutes exempting women from jury service

. . . reflect the historical male prejudice against partici

pation in activities outside the family circle." Johnston &

Knapp, Sex Discrimination by Law: A Study in Judicial Perspec

tive, 46 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 675, 718 (1971). In short, while the

provisions challenged here do not work an absolute denial to

women of their right to serve on juries, they are founded on a

premise, similar to the premise once responsible for the ex-

-11-

elusion of blacks from juries, that women are not equipped to

participate in important community affairs: the Florida pro

visions betray "a view of woman's role which cannot withstand

scrutiny under modern standards." Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 U.S. 625, 639-40' (1971)(concurring opinion).

A clear illustration of the invidious effect of the sup

posedly "benign" classification is the response of a New

York trial court in 1970 to the challenge of a female plain

tiff to a jury system providing automatic exemption for any

woman on request. Plaintiff's "lament," the judge stated,

should be addressed to her sisters who prefer "cleaning and

cooking, bridge and canasta, the beauty parlor and shopping,

to becoming embroiled in plaintiff's problems. . ..." DeKosenko

v. Brandt, 63 Misc.2d 895, 898, 313 N.Y.S.2d 827, 830 (Sup. Ct.

1970). Ignored by the court was the fact that "neither man

nor woman can be expected to volunteer for jury service,"

Alexander, supra at 643 (concurring opinion), that few persons,

male or female, would voluntarily assume all the varied civic

responsibilities imposed on them, and that in failing to re

cognize women as persons with full civic responsibilities as

well as rights, New York, like Florida, displays a view of

women as something less than mature adult citizens.

No compelling state interest could possibly be advanced

f fir i im i rn '^ i m' nrf -r no r>yorir>r»4- <-«“ t JZ 4. u - _______________ _ _ _rr

*----------•* — - * . - * * 5 v—OV—1* C- ^ J - U O O x i XV^U. L.XWU « _L X. L11C U. J_ CS kJ J_

the classification is to provide for the care of young children,

to ensure that they are not left without caretakers when their

parents are called for jury service, the gross technique em

-12-

ployed cannot pass constitutional muster, for it is at the

same time appallingly overbroad and stereotypically under-

inclusive. As the record in this case indicates, almost

one-third of those women who chose the exemption held out

side employment. R. 10 6, 1[ 2. Women whose children are in

school and women whose children are cared for by others are

accorded the same "special treatment" as women in fact re

sponsible for the care of young children; men responsible for

the care of young children are not part of the statutory clas

sification. Other, far more appropriate alternatives are

available to advance the legitimate interest in assuring care

for young children, for example, jury laws which provide

exemption for any "person" responsible for a young child's

care. See N.J.S.A. § 93-1304(12), Thus, under strict scru

tiny, the challenged jury laws and the classification they em

body must necessarily be declared unconstitutional -- no com

pelling interest can be advanced to support them, and other

methods are available to the state to accomplish any legitimate

objectives that the statute might serve.

Frontiero has expressly held that in the realm of "strict

judicial scrutiny . . . any statutory scheme which draws a

sharp line between the sexes, solely for the purpose of achiev

ing administrative convenience necessarily commands 'dissimi

lar treatment for men and women who are . . . similarly situated,'

and therefore involves the very kind of arbitrary legislative

choice forbidden by the Constitution." Reed v. Reed, supra at

77» 76; Frontiero, supra at 690. The argument that women, as

-13-

housekeepers and mothers, do not hold jobs from which absence

is manageable, ignores the reality that many women do not per

form the housekeeper-mother role, that some who do perform that

role have ample assistance at home, and that, particularly in

young families, the home burden is increasingly shared by men

and women. In Levy County fully 31% of the women who were ex

empted from jury service in 1973 have some form of employment

outside the home. R. 10 6, 1[ 2. The Hoyt image of women "as

the center of home and family life," of dubious accuracy for

many women in 1961, is today recognized as a stereotype of the

same order as those firmly rejected as a basis for legislative

line-drawing in Frontiero and Reed.

In 1972, 60% of all married women living with their hus

bands were gainfully employed, and 42% of all working women

were employed full-time the year round. U.S. Women’s Bureau,

Dept, of Labor, Highlights of Women's Employment and Education

(1973). Thus, the Florida jury service exemption for women

covers a substantial population of wives and mothers for whom

homemaking and child care concerns do not preclude active in

volvement outside the home. The Florida classification is

overinclusive and, under Frontiero and Reed, inevitably un

constitutional. The legislative classification here challenged

makes an arbitrary choice premised upon wholly mistaken concep

tions of the role of women in today's world. If it ddvemces

any legitimate objective, it does so in a manner inconsistent

with equal protection standards.

-14-

D » Male Plaintiffs Are Injured as a Matter of Law.

Male plaintiffs claim that the exemption from jury service

extended to women by Florida constitutes an arbitrary, irra

tional and overbroad classification, discriminating against

them and the class they represent in violation of the equal

protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. Recognizing

the important "right" aspect of jury duty, these plaintiffs

point out that jury service has its onerous side, that it is

both "a right and a responsibility that should be shared by

all citizens regardless of sex." White v. Crook, supra at 408.

It is unconstitutional, they claim, to impose upon them, solely

on the basis of their sex, so disproportionate a share of the

'jury service right-responsibility.

The basic premise of the Frontiero and Reed decisions is

that legislative classifications must treat men and women

"similarly circumstanced" alike. The jury service exemption

for women does not treat alike all "similarly circumstanced"

persons — women in precisely the same situation as men for

purposes of the provisions are recipients of "special treat

ment." This exemption places a burden upon men not justified

by any fair and substantial relation to the statutory objective.

The exemption overbroadly relieves women from sharing the bur

den. Men and women similarly circumstanced with regard to an

underlying purpose of the classification in that they are re

sponsible for the care of small children are not treated alike.

In sum, the classification does not advance a legitimate legis

lative objective in a fashion consistent with the constitutional

mandate. -15-

POINT II

THE WOMEN'S EXEMPTION RENDERS AN UNCONSTITUTIONAL

RESULT IN LEVY COUNTY; THE DISTRICT COURT

HAD JURISDICTION AND SHOULD HAVE DECIDED

THE QUESTION IN FAVOR OF THE PLAINTIFFS

A. The Impact is Great-.

The population of Levy County in April of 1970 was 51%

female (Florida Statistical Abstract 1973, Population, By Sex

and Race, By Region and County, in Florida; Table 2.455), Yet

from 1969 to 1973, an average of only 37% of the jury lists

were female. R. 102.

Under the procedures employed by the defendants, each

registered elector receives a questionnaire. See sample ques

tionnaire, R. 94-95. As of April 23, 1973, the active file

of returned questionnaires indicated that 623 women had

exempted themselves under the provisions of Florida Statutes

§ 40.01, which allows pregnant women and mothers of children

under 18 to exempt themselves from jury service. R. 106.

Under the existing system, the names of 1,372 women were

placed in the eligibility file, the file of those whose ques

tionnaires indicated that they were eligible for jury service.

R. 100. Assuming that the 623 women had no other basis for

being exempt, 31% of the women eligible for service used the

exemption to escape their civic obligation.

The rationality of this policy, to say nothing of a test

of compelling state interest, is severely questioned by the

fact that 195 of those who obtained the exemption indicated

that they were employed outside the home. Sixty percent of

all married women living with their husbands were gainfully

-16-

employed. U.S. Women's Bureau, supra.

B . No Three-Judge Court Need Be Convened.

No three-judge court is necessary because (1) no state

officer is a defendant and (2) the plaintiffs are suffering

from an unconstitutional result of a constitutional statute.

1. The Constitutionality of the Statute Itself

is not Attacked, Only the Unconstitutional

Results Reached When They are Enforced.

For purposes of § 2281, there'is a distinction to be

drawn between direct attacks on the constitutionality of a

statute and attacks on the unconstitutionality of the results

obtained by the enforcement of a state statute. In the lat

ter case, an injunction may be issued without concerning it

self with the constitutionality of the statute and it is not

required that a three-judge court be convened for disposition

of the case. Anno., 15 L.Ed. 904, 918 (1966). The present

case fits into this second category. Plaintiffs do not con

tend in their alternative argument that the statutes under

which defendants act are facially invalid. Plaintiffs do al

lege that as a result of their enforcement in their particular

county, illegal results are obtained.

The case law relating to this issue seems to be consis

tent and no conflict between the circuits exists. The Second

Circuit, in Astro Cinema Corp. v, Mackell, 422 F .2d 293 (2nd Cir.

1970) , ruled that a three-judge court need not be convened if

-17"

the attack on the unconstitutionality of the results obtained.

The Third Circuit reached the same result in Spencer v. Kugler,

454 F .2d 839 (3rd Cir. 1972).

2. The Defendants are not "State Officers" for

Purposes of § 2281.

The plaintiffs contend that for purposes of bringing into

operation § 2281, the defendants here are not "state officers."

Whether the officers sued are state officers depends not on

the formal status of the officials, but on the sphere of their

functions regarding the matters in issue. Rorick v. Board of

Comm'rs of Everglades Drainage District, 307 U.S. 208 (1939).

In Rorick, a state officer was charged v.7ith certain duties under

a state statute which had no statewide impact. His execution

of the state statute only affected his locale. He was held not

to be a state officer within the intendment of the predecessor

of § 2281. Such is the case here. The defendants' execution

of the state statutes involved here only affects Levy County.

Since § 2281 is a technical enactment and should be nar

rowly construed, Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246 (1941);

Hall v. Garson, 430 F .2d 430 (5th Cir. 1970), the term "state

officer" should be given its plain meaning and clearly complied

with. A state officer is one with the authority to execute or

administer a statewide policy. Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po,

336 U.S. 368 (1949). State officers are those officers who en

force state laws that embody a statewide concern and the state's

interest. They are not officers who, though acting under a

-18-

state law, do so only as local officials and on behalf of a

locality. Cleveland v. United States, 323 U.S. 329 (1945),

It is clear that the defendants here do not possess the

authority to execute or administer a statewide policy. Nor

are their actions of statewide concern or impact. But they

are officers who, though acting under a state statute, act

only as local officials and on behalf of a locality. Defen

dants' execution of its statutory duty plainly only affects

Levy County. Its actions are not felt outside the boundaries

of its locale. For purposes of § 2281, they are not state

officers. There is no need to convene a three-judge panel.

Although the state of law in this area is inconsistent,

unclear, and in a general condition of disrepair, there seems

to exist a presumption that to be a state officer the indi

vidual must be functioning in a state position and have an

official state title. There have been a few exceptions carved

out, though. For example, a police chief enforcing statutes

of statewide application has been designated a state officer.

Atkins v. Charlotte, 296 F. Supp. 1068 (W.D.N.C. 1969). But on the

whole, there seems to be a requirement that the individual,

to be designated a state officer, must have an official state

title or position.

-19-

POINT III

THE DEFENDANTS HAVE DISCRIMINATED AGAINST BLACK

CITIZENS AS A CLASS IN THE SELECTION OF

___________ PERSONS FOR THE JURY LIST____________

The jury panel should represent a cross-section of the

community, Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396 U.S.

320 (1970); Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 100 '(1970); Labat

v . Bennett, 365 U.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966). In Levy County, the

source for the jury panel is the voter registration list. Sec

tion 40.01, Florida Statutes states that "Grand and petit ju

rors shall be taken from male and female persons . . . who are

fully qualified electors."

In Carter v, Greene County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970), the Su

preme Court held constitutional on its face the Alabama statute

requiring jury commissioners to select for jury service those

persons who are generally reputed to be honest and intelligent

and esteemed in the community for their integrity, good charac

ter and sound judgment. In a dictum the court alluded approv

ingly to a number of traditional qualifications for potential

jurors used by the several states. The Court did not discuss

the requirement that persons selected for jury service be elec

tors. More importantly, it was not faced with a record which

indicated that voter registration would be a grave impediment

to jury service.

While holding the statute constitutional on its farp. on

the same day the Court in Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970),

found a pattern and practice of discrimination. The Court

found that 60% of the persons residing in the county were black,

but only 37% of those on the jury list were black. Id. at 359.

-20-

This statistical disparity is the key to the finding of dis

crimination. These two cases frame the appropriate considera

tion of the claims of racial discrimination in this case.

Levy County is 25% black. R, 101, The lists of persons

from which venires are chosen has varied between 7% and 18%

from 1969 to 1973. R. 102. They have averaged 13.2%. This

means that black strength or representation on juries is ap

proximately 50% of what it should be. This is a much more

dramatic statistical showing than in Turner v. Fouchef supra.

There are three different ways of remedying this depriva

tion. Each way is signficiantly different.

A. Choose Blacks at a Rate Higher than Whites from

the List of Electors

A constitutional result may be reached without tampering

with the existing base for jurors — the elector roll. The

district court could correct the overrepresentation of whites

and the underrepresentation of blacks on the voter registra

tion list by drawing blacks at a higher rate than whites for

the jury panel in order that the jury panel represent a cross-

section of the community. Brooks v. Beto, 366 F .2d 1 (5th Cir.

1966), is authority for drawing blacks at a higher rate. There

the Court stated:

. . . [The Supreme] Court has never treated

Cassell as a declaration against conscious inclu

sion [of blacks] where this is essential to satis-

fy constitutional imperative. Rather, it has Peen

treated as a case of exclusion through a system of

limited inclusion. . . . Id. at 21 (emphasis added).

. . . Although there is an apparent appeal to

the ostensibly logical symmetry of a declaration

forbidding race consideration in both exclusion and

inclusion, it is both theoretically and actually

unrealistic. Id. at 24.

-21-

B. Declare that the Florida Statute Limiting Jurors

to Electors Produces an Unconstitutional Result

and Mandate Selection of Blacks from Other Sources

In Pullam v. Greene, 396 F.2d 251, 257 (5th Cir. 1968),

it was recognized that the constitutional command was "to place

sufficient names on the jury list and in the jury box as to

obtain a full cross-section of the county." A new Georgia

statute on jury selection had been passed which made voter

lists the presumptive source of names for the jury list. But

this Court in looking at the record in the defendant county

noted that only 13% of the voters were blacK while 55% of the

population was black. The Court stated that it was "highly

likely" that affirmative action would be necessary to compen

sate for the inadequacies of the voter roll as a source of ju

rors. Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F .2d 1253 (Sth Cir. 1971),

stands for the same proposition.

The difference in the Florida and Georgia statutes is that

the Georgia statute permits use of other sources to supplement

the yoter rolls, the Florida statute does not. But the result

cannot be different. As Pullam states, these are "federal

constitutional commands."

Because the results in Levy County are unusually severe•

because of the low percentage of black persons registered to

vote, this Court could hold that under the "unconstitutional

result" doctrine of three-judge court jurisprudence, it is un

necessary to convene a three-judge court. See Point II, supra.

C . The Court Could Hold that a Three-Judge Court Be

Convened to Adjudicate the Constitutionality of the

Provision on its Face

-22-

The district court held the question of the constitution-

ality Florida statute to be insubstantial as a matter

of law and failed to convene a three-judge court. The district

court relied on Carter. R. 110-11. First, Carter did not

speak to this question. At best, it spoke in dicta around the

question. Second, and much more important, what Carter did

not present and this case does is a factual context in which

under the current system the limitation of jurors to electors

necessarily yield an unrepresentative panel of jurors.

Carter dealt with vague qualifications which if enforced in

good faith could lead to a constitutional panel. Here we deal

with a clear objective basis which absolutely precludes a cons

titutional result under the procedures now in effect in Levy

County, i.e., random selection from a population of electors.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore plaintiffs-appellants respectfully request that

this court reverse the court below and order the convening of

a three-judge court to adjudicate the constitutionality of

Florida laws exempting women from jury service and

rule that defendants-appellees have discriminated

against black citizens in the selection of

-23-

persons for the jury lists or in the alternative enter its

own order finding such statutes unconstitutional and granting

the relief requested.

Respectfully submitted,

Kent Spriggs

118 N. Gadsden Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

Laughlin McDonald

Emily Carssow

Neil Bradley

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

By s/Neil Bradley_______________

Neil Bradley

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Of Counsel:

Melvin L. Wulf

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

24-