Background on Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education (N.C.) and Wright v. The Council of the City of Emporia (VA)

Press Release

May 24, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Background on Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education (N.C.) and Wright v. The Council of the City of Emporia (VA), 1971. 9f0b9582-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/75cee574-fa57-4327-a08b-29d68ef86268/background-on-cotton-v-scotland-neck-city-board-of-education-nc-and-wright-v-the-council-of-the-city-of-emporia-va. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

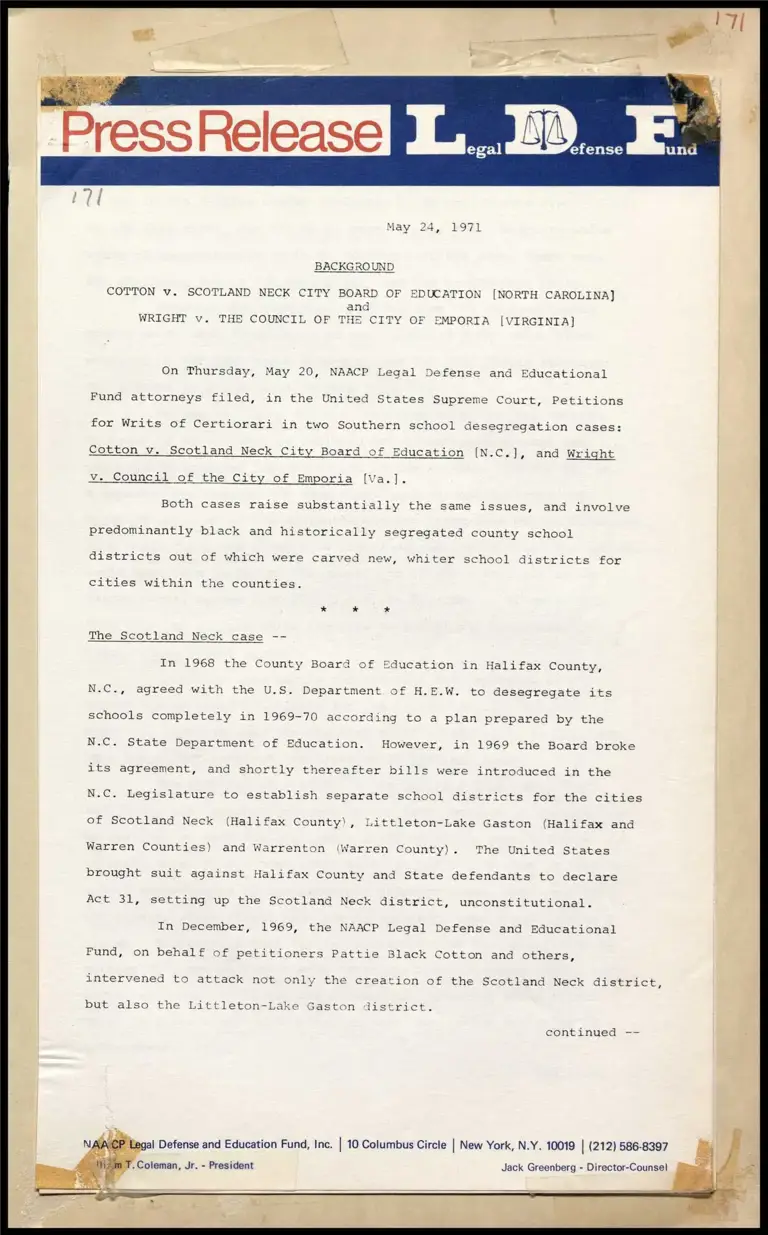

‘Press Release =

May

BACKGROUND

COTTON v. SCOTLAND NECK CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION [NORTH CAROLINA]

and

WRIGHT v. THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF EMPORIA [VIRGINIA]

On Thursday, May 20, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund attorneys filed, in the United States Supreme Court, Petitions

for Writs of Certiorari in two Southern school desegregation cases:

Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education (N.c.], and Wright

v. Council of the City of Emporia [Va.].

Both cases raise substantially the same issues, and involve

predominantly black and historically segregated county school

districts out of which were carved new, whiter school districts for

cities within the counties.

The Scotland Neck case --

In 1968 the County Board of Education in Halifax County,

N.C., agreed with the U.S. Department of H.E.W. to desegregate its

schools completely in 1969-70 according to a plan prepared by the

N.C. State Department of Education. However, in 1969 the Board broke

its agreement, and shortly thereafter bills were introduced in the

N.C. Legislature to establish separate school districts for the cities

of Scotland Neck (Halifax County), Littleton-Lake Gaston (Halifax and

Warren Counties) and Warrenton (Warren County). The United States

brought suit against Halifax County and State defendants to declare

Act 31, setting up the Scotland Neck district, unconstitutional.

In December, 1969, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, on behalf of petitioners Pattie Black Cotton and others,

intervened to attack not only the creation of the Scotland Neck district,

but also the Littleton-Lake Gaston district.

continued --

egal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

«Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

SCOTLAND NECK AND EMPORIA SCHOOL CA PAGE TWO

The district court noted that during the 1968-69 school year

of the 10,655 Halifax County students, 8,196 or 77% were black, 2,357

or 22% were white, and 102 or 1% were Indian; for a black-to-white

ratio of approximately 34 to 1. Within Scotland Neck, there were

695 children: 296 or 43% were black, and 399 or 57% were white.

Removing Scotland Neck students from the Halifax County

system would have resulted in an enrollment of 7,900 (80%) black

students, 1,958 (1 %) white students, and 102 (1%) Indian students;

for a black-to-white ratio of more than 4 to 1.

On May 23, 1970, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern

District of North Carolina declared Act 31 unconstitutional and

permanently enjoined implementation of the statute. On May 26, in

a separate proceeding, the same court held unconstitutional and

enjoined creation of the Warrenton and Littleton-Lake Gaston districts.

(The court found the cumulative effect of setting up these two systems

would have been to reduce the proportion of white students in the

Warren County system from 27% (1,415) to 7% (260) -- allowing more

than four out of five white students to escape the predominantly

black county school system).

Littleton-Lake Gaston and Scotland Neck appealed to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which on

March 23, 1971 affirmed the district court's injunction in Littleton-

Lake Gaston but reversed its decision in Scotland Neck.

The Appeals Court said, in the Scotland Neck case, that

Act 31 was not “unconstitutional on its face" because it appeared to

be designed to meet the legitimate goals of giving Scotland Neck

citizens more control over their schools, permitting them to increase

school expenditures by supplementary property taxes, and preventing

anticipated white flight from the desegregated county public school

system. Recognizing that the legislation served the latter goal by

setting up a system with a more favorable black-to-white ratio, the

Court declared: “It is not the purpose of preventing white flight

which is the subject of judicial concern, but rather the price of

achievement."

continued --

SCOTLAND NECK AND HMPORIA SCHOOL CA

PAGE THI

Because the residual county school system's black proportion

would be only 4:1, compared to 34:1 in the combined unit, the Court

held that the "primary purpose" of the legislation was not to

"maintain as much of separation of the races as possible" and that

it was therefore constitutional.

The Appeals court did sustain the lower court's rejection

of the transfer plan which originally accompanied Act 31, and which

would have permitted 350 white students to transfer into Scotland

Neck and a net of 34 black students to transfer to the residual

Halifax County system, resulting in a 74% white Scotland Neck district.

The appellate court agreed that to permit such a shift would have been

equivalent to resegregation.

The Emporia case --

This suit was begun in 1965 in the U.S. District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia by the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund on behalf of petitioners Pecola Annette Wright and

others, to desegregate the public schools of Greensville County, Va.

After the failure of a "freedom of choice" desegregation plan, the

district court in June, 1969 ordered all six county schools paired,

which prompted the officials of the City of Emporia to seek State

authority to operate a separate city school system. (Prior to this

move, city schoolchildren were educated by the county school board).

On August 1, 1969, LDF asked the district court to enjoin

the proposed separation, and offered evidence from which the court

concluded that the city's actions were racially motivated. A transfer

provision between the separate systems similar to that in the Scotland

Neck case was proposed in this case as well. The district court

temporarily restrained operation of separate districts and scheduled

a full hearing for December. In the interim, according to LDF, the

city changed its tactics and brought in experts to draft an expensive

budget for operation of an independent city school system "superior"

to the county's educational program.

continued --

SCOTLAND NECK AND EMPORIA SCHOOL CASES PAGE FOUR

At the December hearing, city officials testified that, in

their opinion, the county had not and would not make available the

additional funds necessary to maintain educational standards in a

desegregated system, but that city residents would be willing to

pay the increased taxes necessary to operate the “superior” educational

program proposed by the city.

The district court focused on the racial shifts which would

be occasioned by the secession. First, noted the court, the two

school buildings which the city school district would use were those

which had historically been attended by white students prior to the

start of the lawsuit and during the years of "free choice." The

remaining schools had traditionally been attended only by blacks,

and all but one were located outside the Emporia city limits.

The county's school population was 65.9% (2,477) black and

34.1% (1,280) white; a black-to-white ratio of 2 tol. The City of

Emporia had 580 (51.7%) black children and 543 (48.3%) white children;

a black-to-white ratio of 1 to 1.

Pulling the city children out of the county system would

leave 1,999 (72.2%) black students and 728 (27.9%) white students

increasing the black-to-white ratio in the remaining county schools

to) 3 to. 5.

The district court recognized that if the city actually did

spend as much as it proposed in its own school system, it would be

offering a better educational program in some respects than was

available in the county system. However, the court felt the city's

motives were far from entirely non-racial, and in view of its conclusion

that secession of the city would seriously harm the chances for

successful desegregation of the county schools, it refused to permit

the establishment of a new district.

In reversing this decision, as in Scotland Neck, the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit iauded the efforts to provide a

“quality education" for city children, and said that when creation of

a new Cistrict results in "merely a modification . .. rather than

continued --

SCOTLAND NECK AND EMPORIA SCHOOL CASES PAGE FIVE

effective resegregation," separation should be prohibited only if

the "primary purpose . . . is to maintain as much of separation of

the races as possible." As in Scotland Neck, the Court of Appeals

accepted the city's claims that its motives were to have a voice in

the education of its children.

* * *

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorneys are

asking the Supreme Court to hear the case on the grounds that the

Fourth Circuit's “primary purpose" approach and standard for

deciding whether any governmental action is racially motivated:

1) Threatens the rights of black school children guaranteed by

Brown (I),

2) Encourages the creation of new school districts where whites would

enjoy a more favorable racial ratio,

3) Could produce a "quagmire of litigation" in district courts,

4) Conflicts with the Supreme Court's decree that a compelling state

interest be shown where state action has a racially discriminatory

effect,

5) Conflicts with the burden which Green placed upon school boards to

justify desegregation plans less effective than available

alternatives,

6 Fails to give proper weight to the judgments of district judges

charged with framing and implementing desegregation plans, and

7) Conflicts with the decisions of other Courts of Appeals.

oe Ole

NOTE: Please bear in mind that the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. is a completely separate and distinct organization,

even though we were established by the NAACP and retain those

initials in our name. Our correct designation is NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., frequently shortened to LDF.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Attorney Norman Chachkin or ;

Sandy O'Gorman (Public Information

212-586-8397