Reitman v Mulkey Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1967

55 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reitman v Mulkey Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. a206310d-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/75cf3b1e-a85b-4ec5-945d-1089049fa465/reitman-v-mulkey-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

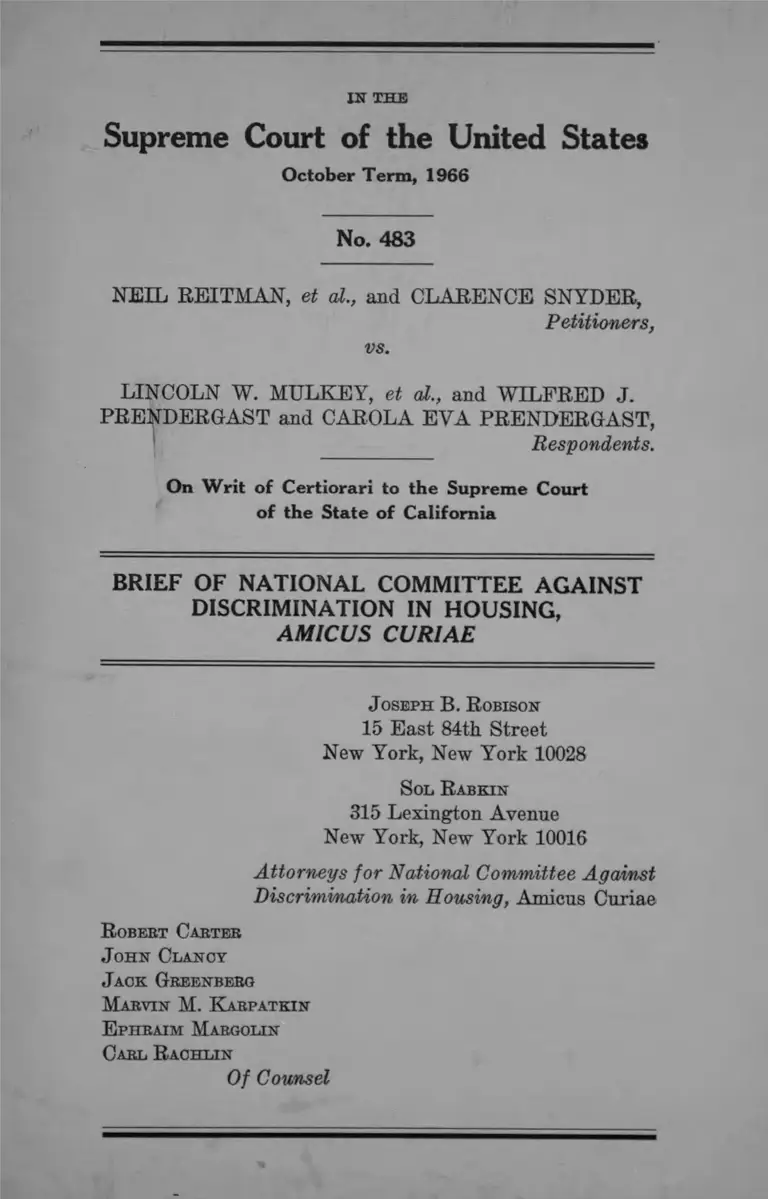

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1966

No. 483

NEIL REITMAN, et cd., and CLARENCE SNYDER,

Petitioners,

vs.

LINCOLN W. MULKEY, et at., and WILFRED J.

PRENDERGAST and CAROLA EVA PRENDERGAST,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

BRIEF OF NATIONAL COMMITTEE AGAINST

DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING,

AMICUS CURIAE

J oseph B. R obison

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Sol R abkin

315 Lexington Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Attorneys for National Committee Against

Discrimination in Housing, Amiens Curiae

R obert Cabteb

J ohn Clancy

J ack Greenberg

Marvin M. K arpatkin

E phraim Margolin

Carl R achlin

Of Counsel

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

PAGB

I nterest op the A mictjs .................................................... 2

Questions to W hich this Brief is A ddressed............. 5

A rgument

P oint One—The State of Califomia has given leg

islative recognition to the existence and evil

effects of discrimination in housing against

minority groups ................................................. 6

A. Discrimination against minority groups

dominates the housing market in California 6

B. Residential segregation in California has

harmful effects ............................................ 8

C. The State of California has recognized the

existence and harmful effects of racial dis

crimination in housing by enacting legis

lation against such discrimination ............ 17

P oint Two—Article I, Section 26 violates the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment by encouraging, empowering and facilitat

ing discrimination in housing against minority

groups .................................................................. 19

A. The Fourteenth Amendment requires the

states to take appropriate action to prevent

inequality in housing................................... 19

B. The momentum of California’s involve

ment in regulation of discrimination in

housing makes its facilitation of discrimi

nation state action within the reach of the

Fourteenth Amendment ............................. 21

IX

C. Article I, Section 26 places tlie support of

the legal system of California behind racial

discrimination in housing........................... 26

D. Article I, Section 26 violates the Equal

Protection Clause because it authorizes

and facilitates racial zoning ...................... 32

E. The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a

state from disabling itself from fulfilling

its constitutional responsibility to assure

equality in housing....................................... 36

P oint T hree— Article I, Section 26 violates the

guarantee in 42 TJ. S. C., Section 1982 of the

right of all citizens of the United States to

equal opportunity to purchase or lease prop

erty without discrimination based on race ...... 38

A. History of Section 1982 ............................. 38

B. The Thirteenth Amendment ...................... 40

C. The Fourteenth Amendment ...................... 41

D. The effect of Section 1982 on Article I,

Section 26 ..................................................... 46

PAGE

Conclusion 47

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Abstract Investment Co. v. Hutchinson, 204 Cal. App.

PAGE

2d 242 (1962) ........................................................... 28

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964) ..............27, 28, 30

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 IT. S. 249 (1953) ................... 28, 29

Bell v. Maryland, 378 IT. S. 226 (1964) ....................... 43

Block v. Hirsh, 256 H. S. 135 (1921) ............................. 25

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 280 F. 2d

531 (C. A. 5, 1960) ................................................. 28

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 H. S. 60 (1917) ..................... 27, 32

Burks v. Poppy Construction Co., 57 Cal. 2d 463

(1962) .................................................................12,17,18

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 H. S.

715 (1961) .............................................................. 27

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 22 (1883) 39,40, 41,44, 45

Clyatt v. United States, 197 U. S. 207 (1905) .............. 39

Eisentrager v. Forrestal, 174 F. 2d 961 (1949), re

versed on other grounds, 339 U. S. 765 (1950) .... 37

Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296 (1966) ...... 22, 23, 24, 25, 27

Gamer v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) .................. 43

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960) ............. 32

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U. S. 218 (1964) ............. 31

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915) ............. 32

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 (1927) ......................... 33

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F. 2d

718 (C. A. 4, 1966) ............................................23, 24, 25

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948) ............................ 41

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal.

2d 876 (1963) ........................................................... 18

X V

Lane v. Wilson, 307 IT. S. 268 (1939) ........................... 32

Lee v. O’Hara, 57 Cal. 2d 476, 370 P. 2d 321 (1962) .... 17

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) ......................25, 34

McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. Ry., 235 IT. S‘. 151

(1914) ...................................................................... 28

Mnlkey v. Reitman, 64 Cal. 2d 529, 413 P. 2d 825 ........ 2

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932) ......................... 26, 28

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U. S. 230 (1957) 23

Prendergast v. Snyder, 64 Cal. 2d 877, 413 P. 2d 847 2

Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704 (1930) .................... 33

Second Slaughter House Case, Butchers’ Union Co.

v. Crescent City Co., I l l U. S. 746 (1883) .......... 36

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ............27, 28, 33,44

Smith v. Albright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944) ..................... 27, 34

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 (1953) ......................... 27

Testa v. Katt, 330 U. S. 386 (1947) ............................. 37

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312 (1921) .................... 24

United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745 (1966) .............43,44

United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629 (1882) .......... 40

United States v. Morris, 125 Fed. 322 (1903) .............. 44

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U. S. 52 (1964) .................. 32

PAGE

y

Statutes:

PAGE

Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1681, pp. 4074-7, Health and Sanity

Code sections 35700-35741 .................................... 17

Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1866, p. 4424, Cal. Civil Code, Secs.

51-52 (1965) ............................................................ 17

Cal. Stats. 1963, c. 1853, Sec. 2, p. 3823 ....................... 18

Civil Rights Act of 1870, ch. 114, 16 Stat. 140 (1870) 39

Civil Rights Act of 1875 ............................................... 45

Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall We

Livef (1958) ....................................................7,9,10,13

42 United States Code:

Section 1982 ....................................................... 6,19,38

Other Authorities:

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors (1955) ....................... 7

50 Am. Jur., Statutes §441 ............................................ 42

California Real Estate Magazine, Yol. XLIY, Issue

No. 2 (1963) ........................................................... 30

Clark, Prejudice and Your Child (1955) 11

Departments of Commerce and Housing and Urban

Development, ‘ ‘ Construction Reports — Sale of

New One-Family Homes,” Series C25-26 (1963),

C25-27 (1964), C25-65-13 (1965) ........................... 33

Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962) 19

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(Johns Hopkins Press, 1908) ............................... 43

Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots

(Dec., 1965), Violence in the City—An End or a

Beginning ................................................................

Groner & Helfield, Race Discrimination in Housing,

57 Yale L. J. 426 (1948) ........................................ 12

V I

Maslow, De Facto Public School Segregation, 6 Vill.

PAGE

L. Rev. 353 (1961) .................................................. 15

McEntire, Residence and Race (IT. Cal. Press,

I960) ........... ..........................................................8,12,33

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) ....................... 7,15

National Committee Against Discrimination in Hous

ing, “ The Fair Housing Statutes and Ordi

nances” (June, 1966) ............................................

New York State Commission Against Discrimination,

In Search of Housing, A Study of Experiences

of Negro Professional and Technical Personnel

in New York State (1959) .....................................

President’s Committee on Civil Rights, Report, To

Secure These Rights (1947) ................................. 7,15

Robison, J. B., “ The Possibility of a Frontal Assault

on the State Action Concept,” 41 Notre Dame

Lawyer 455 (1966) .................................................. 43

United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Re-

,P °rt ............................................................. 7,9,11,12,15

United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Re

port, Book 4, Housing ........................................ 7; 12,13

United States Commission on Civil Rights, “ 50 States

Report” (1961) ....................................................7,14,16

21

15

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948) 7

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1966

No. 483

Neil R eitman, et al., and Clakence Snyder,

Petitioners,

vs.

L incoln W . Mulkey, et al., and W ilfred J. P rendergast

and Carola E va P rendergast,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

BRIEF OF NATIONAL COMMITTEE AGAINST

DISCRIMINATION IN HOUSING,

AMICUS CURIAE

The two proceedings before this Court on writ of cer

tiorari to the California Supreme Court present the single

question whether a provision recently added to the Cali

fornia Constitution violates the Constitution and laws of

the United States. In each case, it was asserted that the

owner of housing accommodations had violated a Cali

fornia statute prohibiting discrimination in the sale or

2

rental of lionsing on the basis of race, religion or national

origin. In each case, the owner asserted that the statute

had been invalidated by a clause added to the California

Constitution by action of the voters on Election Day in

1964, on what was popularly known as “ Proposition 14.”

The operative part of the clause, which is now Article I,

Section 26 of the California Constitution, reads as follows:

Neither the State nor any subdivision or agency

thereof shall deny, limit or abridge, directly or indi

rectly, the right of any person, who is willing or de

sires to sell, lease or rent any part or all of his real

property, to decline to sell, lease or rent such property

to such person or persons as he, in his absolute dis

cretion, chooses.

The Supreme Court of California, on May 10, 1966, is

sued its decisions1 in these cases holding that Article I,

Section 26, violated the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

interest of the Amicus

This brief is filed, with the consent of the parties, on

behalf of the National Committee Against Discrimination

in Housing. The National Committee was founded in 1950.

Its constitution specifies the following purpose:

To eliminate prejudice and discrimination, to lessen

neighborhood tensions, to defend human and civil

rights secured by law, * * *

1. Mulkey v. Reitman, 64 Cal. 2d 529, 413 P. 2d 825; Prender-

gast v. Snyder, 64 Cal. 2d 877, 413 P. 2d 847.

3

Its member organizations are as follows:

A FL-C IO

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of

America, a f l -cio

American Baptist Convention

American Civil Liberties Union

American Council on Human Rights

American Ethical Union

American Friends Service Committee

American Jewish Committee

American Jewish Congress

American Newspaper Guild, a fl -cio

American Veterans Committee

Americans for Democratic Action

Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters,

a fl -cio/ clc

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico,

Department of Labor,

Migration Division

Congress of Racial Equality— core

Cooperative League of the U SA

Friendship House

Industrial Union Department, afl-cio

International Ladies’ Garment

Workers’ Union, afl-cio

International Union of Electrical, Radio

and Machine Workers, a fl -cio

International Union, United

Automobile, Aerospace and

Agricultural Implement Workers

of America (U A W )

Jewish Labor Committee

League for Industrial Democracy

The Methodist Church

naacp Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People— naacp

National Association of Housing

Cooperatives

National Association of Negro Business

and Professional Women’s Clubs

National Catholic Conference for

Interracial Justice

National Committee on Tithing

in Investment

National Community Relations

Adivsory Council

National Council of Churches of Christ

National Council of Jewish Women

National Council of Negro Women

National Urban League

Protestant Episcopal Church

Scholarship, Education and Defense

Fund for Racial Equality

Southern Regional Council

Synagogue Council of America

Union of American Hebrew

Congregations

Unitarian Universalist Association

United Church of Christ

United Presbyterian Church

United Steelworkers of America, afl- cio

Young Women’s Christian Association

The National Committee submits this brief because Ar

ticle I, Section 26 represents, in California and in all other

states, a most potent device for indurating racial segrega

tion in housing. The language of Article I, Section 26 is

general and unqualified. No effort is made to catalogue

the considerations which the amendment would immunize

against state regulation or prohibition in a landowner’s de

termination to withhold property from particular individ-

4

uals. Rather, by vesting ‘ ‘ absolute discretion” in the prop

erty owner with respect to the disposition of his property,

the amendment attempts to extend state constitutional pro

tection to both reasonable and unreasonable motivations,

ethical and unethical considerations, reasons that under

mine the general welfare as well as those that do not, for

selecting and rejecting willing buyers and renters.

The major impact of the amendment falls upon mem

bers of minority groups. A constitutional amendment was

not needed to permit property owners to withhold a lease

hold from lessees with pets, to withhold property in a sen

ior citizens community from purchasers who do not meet

an age requirement, or to withhold property for any num

ber of considerations under commonly accepted tenets of

desirable social and economic behavior. However, in re

cent years, the withholding of real property on purely ra

cial or religious grounds and the resultant creation of

segregated housing which denies equal opportunity for one

of the essentials of living has been made the occasion for

legal redress in California. Article I, Section 26 was pro

posed and passed for the precise objective of reversing

that trend by granting and guaranteeing the right to dis

criminate on racial and religious grounds in the selling and

leasing of real property.

The language of the amendment achieves that purpose.

Under the phraseology used—“ absolute discretion” and

“ decline to sell” —all Mexicans seeking homes in Los An

geles may be turned away because of their national origin

by owners whose houses are on the market; all Japanese

farmers may be denied farmland in the San Joaquin Valley

5

because they are not Caucasian; all Negroes in San Fran

cisco may be told that they cannot rent apartments because

of the color of their skin; all Jews may be excluded from

a housing project because of the way they worship God.

In those instances, at least, the amendment undeniably

would sanction discrimination. It would even legalize total

exclusion of specified groups from whole communities.

It is the position of Amicus that Article I, Section 26

of the California Constitution, hy granting immunity from

the sanctions of state law to those who discriminate against

minority groups in selling or leasing homes, by withholding

redress of state law from those who suffer such discrimi

nation and by arbitrarily precluding the effective exercise

of state power to deal with the evils and dangers to the

state resulting from discrimination in the transfer of real

property, is in conflict with the Constitution and laws of

the United States.2

Questions to Which this Brief is Addressed

1. Whether, in view of the fact that discrimination

against minority groups dominates the market for housing

and deprives minority groups of equal opportunity to ob

tain housing, California, by adopting Article I, Section 26

2. W e have been authorized by the following organizations to

state that they support the arguments set forth in this brief and wish

to be viewed as joining in its presentation: A F L -C IO ; American

Civil Liberties Union; American Jewish Committee; American Jew

ish Congress; Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith; Industrial

Union Department, A F L -C IO ; International Ladies’ Garment W ork

ers’ Union, A F L -C IO ; International Union, United Automobile,

Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America

( U A W ) ; N A A C P Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.;

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; and

Scholarship, Education and Defense Fund for Racial Equality.

6

has violated its obligation to take appropriate action to

prevent inequality in housing imposed upon it by the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether Article I, Section 26 violates the guarantee

in 42 IT. S. C., Section 1982 of the right of all citizens to

equal opportunity to purchase or lease property without

discrimination based on race.

A R G U M E N T

P O I N T ONE

The State of California has given legislative recog

nition to the existence and evil effects of discrimina

tion in housing against minority groups.

A . Discrimination against minority groups dominates

the housing market in California

The ghetto pattern that disfigures residential areas

throughout the United States, including California, has

been revealed in every study made of the subject, whether

by public agencies or by private institutions. It means, in

practice, that almost every housing unit placed on the mar

ket, for sale or rental, for slum dwellers or for millionaires,

bears an invisible label marking it as available for whites

only or for Negroes only. As a result, large numbers of

Negroes and members of other minority groups are denied

the opportunity to purchase housing adequate for their

needs which they could otherwise afford and are compelled

to live in racially segregated areas of poorer quality and

status.

7

In 1961, the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights ob

served :3

In 1959 the Commission found that “ housing * * *

seems to he the one commodity in the American mar

ket that is not freely available on equal terms to every

one who can afford to pay.” Today, 2 years later, the

situation is not noticeably better.

Throughout the country large groups of American

citizens—mainly Negroes but other minorities too—are

denied an equal opportunity to choose where they will

live. Much of the housing market is closed to them for

reasons unrelated to their personal worth or ability to

pay. New housing, by and large, is available only to

whites. And in the restricted market that is open to

them, Negroes generally must pay more for equivalent

housing than do the favored majority. “ The dollar in

a dark hand” does not “ have the same purchasing

power as a dollar in a white hand.”

And the California Advisory Committee to the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights has reported :4

The State of California has a large and increasing

Negro population. These people live mainly in segre

gated patterns in the major urban centers of the State.

In most cases, Negro housing areas are considerably

less attractive than housing in other areas.

# # #

3. Report of the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, Book 4,

Housing, p. 1 (1961). See also, Report of the President’s Commit

tee on Civil Rights, To Secure These Rights, pp. 67-70 (1947) ;

Myrdal, An American Dilemma, pp. 618-27 (1944) ; Weaver, The

Negro Ghetto (1948) ; Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors, pp. 70-81

137-49, 150-190, 227-243 (1955) ; Commission on Race and Hous

ing, Where Shall We Live?, pp. 1-10 (1958) ; Report of the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights, pp. 336-374 (1959).

4. U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, “ 50 States Report” pp

43-46 (1961). f W

8

As California’s Negro population increases, pres

sure builds up in the great urban ghettos, and slowly

but perceptibly the segregated areas enlarge. The

Committee found that, as a general rule, Negro fami

lies do not move individually throughout the commu

nity. They move as a group. This is true in most

cases of the relatively high-wage Negro professional

group. It is practically universally true of Negroes

in the lower mass group.

This Negro housing problem is widespread. Ne

groes encounter discrimination not only where houses

in subdivisions and in white neighborhoods are con

cerned but also in regard to trailer parks and motels.

Testimony received by the Committee indicated that

the trailer-park situation is particularly acute and

that, especially in the southern part of the State, few,

if any, trailer parks will accept Negroes.5

Unquestionably there is an established pattern of segre

gation in housing, and in the sale and rental of real estate,

in California.

B. Residential segregation in California

has harmful effects.

Because of the pervasive nature of discrimination in

housing, we have in effect two housing markets, one for

whites and one for non-whites. The resulting oppressive

effects on the direct victims of discrimination and on the

interests of the state as a whole are readily demonstrated.

5. The existence of housing bias in California’s two principal

metropolitan areas is further documented in McEntire, Residence

and Race (1960), in a chapter (pp. 32-67) studying residential pat

terns in 12 large cities representing the major regions of the country,

including Los Angeles and San Francisco. See particularly the maps

showing racial concentration in those two cities, pp. 61-66.

9

1. The most obvious price paid by those who are dis

criminated against is a loss of freedom. “ The opportunity

to compete for the housing of one’s choice is crucial to

both equality and freedom,” declares the Commission on

Race and Housing.0

Within their financial limits, majority groups in Amer

ica are free to choose their homes on the basis of a number

of factors germane to their pursuit of happiness : the size

of house needed to accommodate the family; preferences

for particular styles of housing or kinds of neighborhoods;

the availability of community facilities such as churches,

schools, playgrounds, clubs, shopping, and transportation.

This freedom of choice is denied members of minority

groups. Granted the means a non-white person may buy

any automobile, any furniture, any clothing, any food, any

article of luxury offered for sale. But it is not possible

for a non-white American to bargain freely, in an open,

competitive market, for the home of his choice, regardless

of his intellect, integrity or wealth.

The U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, referring to the

“ white noose around the city,” has said:6 7

There may be relatively few Negroes able to afford

a home in the suburbs, and only some of these would

want such homes, but the fact is that this alternative

is generally closed to them. It is this shutting of the

door of opportunity open to other Americans, this con

finement behind invisible lines, that makes Negroes

call their residential areas a ghetto.

6. Report of Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall

W e Live?, p. 3 (1958).

7. Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Report, p. 378.

10

Housing discrimination also abridges the right of the

majority group owner freely to sell or rent his property.

The mechanics of the dual, segregated housing market re

strict the market within which the white seller may find

prospective purchasers. For practical purposes, he is com

pelled by the prevailing practices in the housing market

to offer his house to whites only or to Negroes only.

2. Housing discrimination imposes a heavy economic

penalty on the Negro. As the H. S. Commission on Civil

Rights pointed out in the portion of its 1961 Report quoted

above, “ Negroes generally must pay more for equivalent

housing than do the favored majority.” 8 This is because

the discriminatory practices that hold down the supply of

housing available to Negroes inevitably raise the price or

rent they must pay.

McEntire, after reviewing all past studies as well as

those conducted for the Commission on Race and Housing,

concluded :9

Racial differences in the relation of housing equal

ity and space to rent or value can be briefly summa

rized. As of 1950, nonwhite households, both renters

and owners, obtained a poorer quality of housing than

did whites at all levels of rent or value, in all regions

of the country. Nonwhite homeowners had better

quality dwellings than renters and approached more

closely to the white standard, but a significant differen-

8. Similarly, the Commission on Race and Housing, in its Re

port, Where Shall W e Live? (1958), p. 36, said: “ * * * segregated

groups receive less housing value for their dollars spent than do

whites, by a wide margin.”

9. Op. cit. supra, p. 155.

11

tial persisted, nevertheless, in most metropolitan areas

and value classes. * # *

3. Other, less tangible, injuries are inflicted on the vic

tims of discrimination in housing, with resultant evil ef

fects on the state itself.10 “ All of our community institu

tions reflect the pattern of housing,” the president of the

Protestant Council of New York has stated. “ It is inde

scribable, the amount of frustration and bitterness, some

times carefully shielded, but the anger and resentment in

these areas can scarcely be overestimated and can hardly

be described; and this kind of bitterness is bound to seep,

as it has already seeped, but increasingly, into our whole

body politic.” He said he could “ think of nothing that is

more dangerous to the nation’s health, moral health as

well as physical health, than the matter of these ghettos.” 11

Residential discrimination and segregation impede the

social progress and job opportunities of minority groups,

and deprive the whole community of the contributions

these Americans might otherwise make. It is questionable

whether we can fully comprehend the enormous harm to

the individual and to the community in terms of waste of

human and economic resources.

4. Perhaps the most notorious effect of the ghetto sys

tem is its creation of slums, with all their attendant evils

•—to the slum dweller and to the public weal. As we have

seen, housing bias compels non-white groups to live in the

10. See, in particular, Clark, Prejudice and Your Child (1955),

pp. 39-40.

11. U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Report, p. 391.

12

restricted areas available to them. The California Supreme

Court summarized the results as follows in Burks v. Poppy

Construction Co., 57 Cal. 2d 463, 471 (1962):

Discrimination in housing leads to lack of adequate

housing for minority groups [citations omitted], and

inadequate housing conditions contribute to disease,

and immorality.

In 1959, the TJ. S. Commission on Civil Eights described

the effects of residential discrimination as follows: “ The

effect of slums, discrimination and inequalities is more

slums, discrimination and inequalities. Prejudice feeds on

the conditions caused by prejudice. Restricted slum living

produces demoralized human beings—and their demoral

ization then becomes a reason for ‘keeping them in their

place’ * * * Not only are children denied opportunities but

the city and nation are deprived of their talents and pro

ductive power.” The Commission reported that a former

Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare estimated the

national economic loss at 30 million dollars a year, repre

senting the diminution in productive power of those who

by virtue of the inferior status imposed upon them were

unable to produce their full potential.12

Two years later, the Commission reiterated its conclu

sion and added: “ These problems are not limited to any

one region of the country. They are nationwide and their

implications are manifold * * *” 13

12. U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1959 Report, p. 392;

Commission on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 5, 36-38; Gro-

ner & Helfeld, Race Discrimination in Housing, 57 Yale L. T. 426,

428-9 (1948).

13. U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Report, Book 4,

“ Housing,” p. 1. See also McEntire, op. cit. supra, pp. 93-94.

13

5. Tlie racial patterns of the slums resulting from

housing bias severely impede programs of slum clearance

and urban renewal. The price paid for these civic improve

ments in terms of forced moves and disrupted lives, is

often borne most heavily by the minority families that live

in the cleared areas.

The problem has been fully described by the U. S. Com

mission on Civil Rights.14 It points out that minorities are

frequently the principal inhabitants of the areas selected

for slum clearance or urban renewal.15 16 But each of these

programs depends for success on the ability to relocate

some or all of the slum dwellers. Urban renewal obviously

contemplates the destruction or renovation of obsolete slum

buildings, the residents of which must of course move. If

they are simply moved to another segregated area, adding

to its population densities, a new slum is created. In those

circumstances, the renewal program represents little in the

way of net reduction of slums.

As Albert M. Cole, former Federal Housing and Home

Finance Administrator, has said:18

14. U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1961 Report, Book 4,

“ Housing,” c. 4 : “ Urban Renewal,” especially pp. 82-83. See also

Commission on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 37-40.

15. From the beginning of the Federal urban renewal program in

1949 up to 1960, slum clearance and urban renewal projects had re

located 85,000 families. Of the 61,200 families whose color is known,

69% were non-white. Housing & Home Finance Agency, Reloca

tion from Urban Renewal Project Areas through June i960, p. 7

(1961).

16. “ What is the Federal Government’s Role in Housing?” A d

dress to the Economic Club of Detroit, Feb. 8, 1954, quoted in Re

port of the Commission on Race and Housing, Where Shall W e

Live?, p. 40 (1958).

14

Regardless of what measures are provided or de

veloped to clear slums and meet low-income housing

needs, the critical factor in the situation which must

he met is the fact of racial exclusion from the greater

and better part of our housing supply. * * * No pro

gram of housing or urban improvement, however well

conceived, well financed, or comprehensive, can hope

to make more than indifferent progress until we open

up adequate opportunities to minority families for de

cent housing.

The California Advisory Committee to the U. S. Com

mission on Civil Rights discovered that these factors were

in full operation in that State, with clearly visible harm

to the Negro population. It reported:17

The Committee found that concentration of Negro

families into certain specified areas within California

cities seems to be augmented, rather than alleviated,

by urban renewal projects. It appears that Negroes

displaced by such projects tend to find alternative

housing in pre-existing Negro sections. There seems

to be little effort to guide displaced families in their

selection of homesites. The project moves forward

and Negro families along with other groups, must

quickly find new homes. More often than not these

Negro families settle in adjacent ghettos already in

existence.

As the proportion of minority group members is

extremely high in the so-called “ blighted areas” of

our State’s larger cities, this is a major problem for

those concerned with civil rights and minority hous

ing.

17. 50 States Report, supra, p. 45.

15

6. The harmful effects of residential segregation are

not limited to housing. A conspicuous feature of the ghetto

system is its tendency to produce segregation in education

and all other aspects of our daily lives.18 19 It is primarily

responsible for the wide-spread de facto segregation that

hampers Negroes and persons of Puerto Rican and Mex

ican origin in urban public schools.18 It has even impaired

the job opportunities opened up by fair employment laws.20

One of the most disturbing features of the physical pat

tern of segregation, whether in housing or otherwise, is

that it builds the attitudes of racial prejudice which, in

turn, strengthen the segregated conduct patterns. This

was recognized two decades ago by a Presidential Commit

tee :21

For these experiences demonstrate that segregation

is an obstacle to establishing harmonious relationships

among groups. They prove that where the artificial

barriers which divide people and groups from one an

other are broken, tension and conflict begin to be re-

18. Myrdal, An American Dilemma, p. 618 (1944) ; Commission

on Race and Housing, op. cit. supra, pp. 35-36.

19. Maslow, De Facto Public School Segregation, 6 Vill. L. Rev.

353, 354-5 (1961). In its 1959 Report, the U. S. Commission on

Civil Rights said (at p. 545) : “ The fundamental interrelationships

among the subjects of voting, education, and housing make it impos

sible for the problem to be solved by the improvement of any one

factor alone.” See also pp. 389-90.

20. N. Y . State Commission Against Discrimination, In Search

of Housing, A Study of Experiences of Negro Professional and Tech

nical Personnel in New York State (1959).

21. Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, To Se

cure These Rights, pp. 82-7 (1947),

16

placed by cooperative effort and an environment in

which civil rights can thrive.22

7. All the evils discussed above combine to create the

gravest danger of all to the security of society—the ever

present threat of violent race conflict. Virtually every in

stance of such violence in the last two decades—outside

of the South—has reflected the ghetto system. It has arisen

either out of efforts by Negro families to move into pre

viously all white areas or out of the tensions that build up

within the ghetto. It is enough to remind this Court of

the riots of 1965 in the Watts and other Negro districts of

Los Angeles that caused the loss of 34 lives and property

damages estimated at $40,000,000.23 California would not

have had a Watts riot if it had not had a Watts in the first

place.

22. The impact of housing discrimination is not limited to citi

zens of our country. The California Advisory Committee to the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights confirms this (SO States Report, supra,

p. 46) :

Discrimination in housing directed against Negroes has had

an unfortunate impact on foreign students whose skin colors are

dark. The Committee heard testimony from an Indian student

at Sacramento State College who indicated that he had been re

fused accommodations in a number of instances because of his

color. The testimony of student government leaders at the same

school indicated that this foreign student problem is significant.

Commendably, student groups at Sacramento State are trying to

do something about this situation through investigation and con

ference.

The Committee is very disturbed by the evident impact of

discriminatory treatment on foreign students whose preconcep

tions about American democracy have been rudely upset. These

students are potential leaders in their own countries and the

image of America which they take back with them can be sig

nificantly tarnished by such experiences.

23. “ Violence in the City— An End or a Beginning,” Report by

the Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots (Dec., 1965),

p. 1.

17

C. The State of California has recognized the existence

and harmful effects of racial discrimination in housing

by enacting legislation against such discrimination.

The State of California has given formal recognition

to the existence and evil effects of discrimination based on

race, religion or national origin by the enactment of anti

bias legislation. It is true that, as we note below, its policy

has been far from consistent, particularly in housing. At

times, in fact, its laws have affirmatively facilitated and

even required discrimination. In recent years, however,

until the approval of Article I, Section 26 by referendum,

the California Legislature has recognized reality by moving

progressively to curb' the ghetto system.

In 1959, California enacted a measure known as the

“ Hawkins Act” which prohibited discrimination in “ pub

licly assisted housing accommodations.” 24 In the same

year, it adopted the “ Unruh Act” which revised its law

dealing with places of public accommodation to make it

applicable to “ all business establishments of every kind

whatsoever.” 25 26 This law was subsequently held to apply

to those in the business of selling or leasing residential

housing.28

24. Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1681, pp. 4074-7, Health and Safety Code,

sections 35700-35741.

25. Cal. Stats. 1959, c. 1866, p. 4424, Cal. Civil Code, Secs. 51-

52 (1965).

26. Lee v. O’Hara, 57 Cal. 2d 476, 370 P. 2d 321 (1962) (real

estate brokers) ; Burks v. Poppy Construction Co., 57 Cal. 2d 463

(1962) (developer of a tract of single family homes).

18

In 1963, California enacted the measure popularly

known as the “ Rumford Act,” which added sections 35700-

35744 to the Health and Safety Code27 and replaced the

provisions of the “ Hawkins Act.” The Rumford Act was

broader than the Hawkins Act in covering, inter alia, res

idential housing containing more than four units, even

though not publicly assisted. In addition, the Legislature

vested the exclusive authority to administer the Rumford

Act in the Fair Employment Practice Commission. The

legislative policy which the Rumford Act implemented is

expressed as follows (Health and Safety Code, sec. 35700):

The practice of discrimination because of race, col

or, religion, national origin, or ancestry in housing ac

commodations is declared to be against public policy.

This part shall be deemed an exercise of the police

power of the State for the protection of the welfare,

health, and peace of the people of this State.

The existence and evil effects of discrimination in hous

ing have been recognized not only by the legislative branch

of the state government but also by its judicial branch.

Burks v. Poppy Construction Co., supra, 57 Cal. 2d at 471;

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal. 2d 876,

881 (1963).

27. Cal. Stats. 1963, c. 1853, Sec. 2, p. 3823.

19

P O I N T T W O

Article I, Section 26 violates the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by encouraging,

empowering and facilitating discrimination in hous

ing against minority groups.

A . The Fourteenth Amendment requires the states to take

appropriate action to prevent inequality in housing.

Article I, Section 26, if valid, would disable the state

and local legislative bodies of California from acting to

prevent discrimination by the owners of housing in sales

or rentals.28 It would also preclude the state judiciary

from developing and applying common law principles that

limit such discrimination in any manner. At one stroke,

it would greatly limit if not undo the effect of all existing

state regulation in this field, prohibit future action at any

level of state government and assure to private owners of

realty freedom from any state restraint on creation of the

discriminatory housing conditions that create many of

California’s serious social problems. We suggest that the

strictures of the Fourteenth Amendment cannot be so easily

avoided in matters of governmental responsibility.

28. Article I, Section 26 applies only to sales and rentals by the

property owner. Presumably, therefore, it leaves the existing state

laws in effect insofar as they apply to discrimination initiated by real

estate brokers and discrimination by banks and other institutions in

the financing of housing. It also goes without saying that this pro

vision, even if valid, does not suspend the limitations of the Thir

teenth and Fourteenth Amendments insofar as they apply to housing

benefited by “ state action.” Neither does it affect the power of the

Federal Government to deal with housing bias by legislation, such

as 42 U. S. C. Sec. 1982 referred to below, or by executive action,

such as the Executive Order issued by President Kennedy in 1962

barring discrimination in housing receiving certain forms of Federal

assistance. Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962).

20

The purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to pro

tect the rights of minority groups with respect to activities

in which, under our political system, the state is expected

to play a role. When this Court originally construed that

Amendment as dealing only with “ state action,” it did so

on the assumption that the states would act appropriately

to prevent abuse of their legal systems so as to permit de

nials of equal opportunity. Thus, in the Civil Rights Cases,

109 U. S. 3 (1883), where it held that the Federal Govern

ment did not have power to prohibit discrimination by pri

vate parties in operating places of public accommodation,

it proceeded on the assumption that individual rights “ may

presumably be vindicated by resort to the laws of the State

for redress” (109 XL S. at 17). It said (at 19):

We have discussed the question presented by the law

on the assumption that a right to enjoy equal accom

modation and privileges in all inns, public conveyances,

and places of public amusement, is one of the essential

rights of the citizen which no State can abridge or in

terfere with. Whether it is such a right, or not, is a

different question which, in the view we have taken of

the validity of the law on the ground already stated,

it is not necessary to examine.

It also said (at 25):

Innkeepers and public carriers, by the laws of all the

States, so far as we are aware, are bound, to the extent

of their facilities, to furnish proper accommodation to

all unobjectionable persons who in good faith apply for

them.

This Court thus made it plain that our federal system

of government posits a responsibility on the part of the

states to prevent inequality through protection of individual

21

rights. That responsibility, like “ state action,” is an ex

panding concept. Governmental responsibility generally

has necessarily grown with the proliferation of complex

problems in contemporary life. State and individual have

more points of contact today than in years gone by. In

the same way, the need for state action to insure equality

in basic rights has grown.

As we have shown in Point One, California is scarred

by minority group ghettoes that cause severely harmful

effects both for the minority groups directly affected and

for the public at large. Those evil effects have been high

lighted by the tragic events of the Watts riots of 1965 and

the official report on its causes and consequences.

California, like 16 other states,29 has recognized the ob

ligation that these facts impose upon it by enacting appro

priate legislation to curb housing bias. By now adopting

Article I, Section 26, which in effect repudiates that obli

gation, California has violated the mandate of the Four

teenth Amendment.

B. The momentum of California’s involvement in regula

tion of discrimination in housing makes its facilitation

of discrimination state action within the reach of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

What is at stake here is the shaping of residential areas.

To a large extent, in our present complex society, that is

already done or controlled by state action—in the form of

zoning regulations, building restrictions, control over con-

29. The statutes are listed and summarized in “ The Fair Hous

ing Statutes and Ordinances,” Report of the National Committee

Against Discrimination in Housing (June, 1966).

22

struction of roads and other forms of transportation as well

as the supply of public utilities and many other factors

that determine the nature of a community. Where there is

no regulation by the state of sales and rental policies, those

who own and control housing have the power to create a

pattern of segregation and impose it on a state’s entire

complex of residential areas. Experience shows that they

do just that and that the result is that large segments of

the population are denied equal opportunities because of

their race, religion or national origin and are consequently

compelled to live in squalid, disease-breeding ghettoes

which create festering dangers to society.

On the basis of that experience, California recast its

laws so as to break the pattern of segregated housing. We

submit that this was, in effect, a fulfillment of its obliga

tion, discussed in the preceding section, to use its legisla

tive powers to create and enforce individual rights so as

to prevent inequality. But whether or not we are right in

this, it is plain that regulation of the racial character of

neighborhoods so as to prevent denial of equality has be

come an accepted aspect of government in California.

Whether or not California has an obligation to undertake

such regulation, it has done so. We submit that this Court’s

decision in Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296 (1966) estab

lishes that any further action by the state in this area must

be judged on the basis of whether or not it facilitates dis

crimination, even by private parties.

In the Evans case, the city of Macon, Georgia, had be

came involved in the administration of a public park un

der a private will which limited use of the park to white

23

persons. The city had recognized in recent years that,

under the Fourteenth Amendment, it could not exclude Ne

groes from the park. See Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts,

353 U. S. 230 (1957). A suit was brought in the Georgia

courts by the Board of Managers of the park against the

city to compel it to resign as trustee so that the provision

of the will requiring exclusion of Negroes could be ob

served. The city thereupon tendered its resignation which

was accepted and private trustees were appointed by the

state court. The only reason for the appointment of the

private trustees was to enable Negroes to be excluded from

the park.

This Court reversed the action of the state court on

grounds which are pertinent to the present case. It pointed

out that, ‘ ‘ The action of a city in serving as trustee of prop

erty under a private will serving the segregated cause is

an obvious example” of “ [Cjonduct that is formally ‘ pri

vate’ ” but which has “ become so entwined with govern

mental policies or so impregnated with a governmental

character as to become subject to the constitutional limita

tions placed upon state action.” Evans v. Newton, 382

U. S. at 299. The essence of the opinion was that the

state-private involvement which brought about Fourteenth

Amendment control had not become “ disentangled” (id.

at 302).

The same week that this Court decided Evans v. Newton,

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

decided Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.

2d 718 (C. A. 4, 1966). The plaintiff in that case, a Negro,

sued for admission as a member of the North Carolina

24

Dental Society, basing his claim primarily upon the fact

that members of the society, by statute, elected the State

Board of Dental Examiners, a governmental body. Follow

ing the filing of the case, the state repealed the statute. The

court nevertheless took note of the fact that, in actual prac

tice, the Dental Society still exercised the powers it had had

under the statute. Accordingly, the court held that the limi

tations of the Fourteenth Amendment still applied and that

the plaintiff was entitled to admission to this state agency.

These oases, Evans and Hawkins, have the common char

acteristic that, once state control attaches, bringing in Four

teenth Amendment limitations, repeal of the legislation or

other termination of the state control does not automati

cally remove the impact of those limitations. At the very

minimum, the burden is upon those formerly subject to the

limitations to show that there has been complete “ disen

tanglement. ’ ’

In this case, the State of California had enacted fair

housing legislation. This legislation was not a mere fortui

tous sally into the area of housing regulation. It was a rec

ognition by the State that it had a duty under its police

power to take action against housing discrimination in order

to prevent and eliminate inequality and other serious social

evils. Having recognized its obligation and having pro

vided a remedy to enforce the right to that protection, the

state cannot now divest that right. Indeed, Evans and

Hawkins are but particular examples in a racial context of

the constitutional rule established by this Court in Truax

v. Corrigan, 257 U. S, 312, 329 (1921).

It is true that no one has a vested right in any par

ticular rule of the common law, but it is also time that

25

the legislative power of a State can only be exercised

in subordination to tbe fundamental principles of right

and justice which the guaranty of due process in the

Fourteenth Amendment is intended to preserve, and

that a purely arbitrary or capricious exercise of that

power whereby a wrongful and highly injurious inva

sion of property rights, as here, is practically sanc

tioned and the owner stripped of all real remedy, is

wholly at variance with those principles.

Implicit in the Evans and Hawkins rulings is. the concept

that it is the fact rather than the legal structure of unequal

protection that determines application of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The State will not be allowed to avoid its

constitutional obligation by attaching or removing labels

or by fraudulently seeming to wash its hands of a respon

sibility which it cannot in truth avoid.

Over a period of years, the State of California enacted

a series of laws which recognized that its pre-existing legal

system resulted in unequal opportunity, because of race, to

obtain, a “ necessary of life.” Block v. Hirsh, 256 U. S. 135,

156 (1921). In Evans, this Court said, “ * * * when private

individuals or groups are endowed by the State with powers

or functions governmental in nature, they become agencies

or instrumentalities of the State and subject to its constitu

tional limitations” (382 U. S. at 299). It also quoted its

earlier holding in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 509

(1946), that a State may not permit private enterprises “ to

govern a community of citizens so as to restrict their funda

mental liberties * * #.”

By repudiating the responsibility it acknowledged when

it adopted its laws against discrimination in housing, to deal

2 6

with, the evil of housing bias, California has done what these

cases say it may not do. It has restored the system under

which every housing unit placed on the market by private

enterprise carries a label marking it as available only to

members of one race. It has. given private builders and

other owners of real property the power not merely to

“ govern” communities but to create them in a manner that

restricts “ fundamental liberties.”

It is also important that this Court, in Evans, recognized

that discrimination in the park in question might not have

been unconstitutional if the City had never been involved

but that the involvement of the City created a “ momentum”

that could not simply be turned off by City withdrawal (382

U. S. at 301). So here, the state, recognizing the funda

mental inequality in housing opportunity created under its

laws, undertook to exercise its police power to bring about

equality. Its present reversal o f that decision constituted

affirmative action in support of inequality that violated

“ the mandates of equality and liberty that bind officials

everywhere.” Nixon v. Condon, 286 II. S. 73, 88 (1932).

C. Article I, Section 26 places the support of

the legal system of California behind

racial discrimination in housing.

The decisions of this Court establish that racial dis

crimination by private individuals is not wholly beyond the

reach of the Fourteenth Amendment. While it has held

that there must be a nexus between individual action and

the state in order to bring the Federal Constitution into

play, state involvement need not rise to the level of direct

27

or affirmative action to trigger application of the Amend

ment.

A state law requiring individual discriminatory acts30

is perhaps the most obvious form of state action through

individual conduct hut the application of the Fourteenth

Amendment has not been limited to such flagrant situations.

A state cannot exculpate itself merely by showing that a

private person made the effective determination to engage

in invidious discrimination or some other invasion of funda

mental rights.31 Implication of the1 state through official

authorization or encouragement of unequal treatment of the

races,32 through the availability of its sanctions in support

of such inequality,33 or through failure to act in an area of

state responsibility involving discriminatory conduct,34 all

have provided the occasion for invocation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The new amendment to the California Constitution

places the state’s legal system squarely behind private acts

of housing discrimination. The landlord who would deny

Negroes the opportunity to rent or purchase is given the

signal to proceed. But discrimination authorized or en

couraged by the state has consistently been condemned un

der the Fourteenth Amendment, even though the decision

to discriminate is left to private choice. See, e.g., Shelley

30. Buchanan v. Worley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917).

31. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ; Burton v. Wilming

ton Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961).

32. Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964).

33. Shelley v. Kraemer, supra.

34. Smith v. Allright, 321 U. S. 649 (1 9 4 4 ); Terry v. Adams,

345 U. S. 461 (1953 ); Evans v. Newton, 382 U. S. 296 (1966).

28

v. Kraemer, 384 U. S. 1 (1948); Barrows v. Jackson, 346

U. S. 249 (1953); Anderson v. Martin, 375 TJ. S. 399 (1964);

McCabe v. Atchison T. <& S. F. Ry., 235 U. S. 151 (1914);

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932); Boman v. Birming

ham Transit Company, 280 F.2d 531 (C. A. 5, 1960).

The new amendment implicates state agencies in dis

criminatory practices in a manner no different in principle

than was the case in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra. There the

enforcement of private discriminatory practices by state

courts was determined to be state action within the Four

teenth Amendment. Under the new amendment, the state

judiciary is brought into play on the side of discriminatory

practices in an equally meaningful way, i.e., through pro

tecting the act of discrimination against legal interference.

The point is illustrated by Abstract Investment Co. v.

Hutchinson, 204 Cal. App. 2d 242 (1962), where the court

concluded that a Negro might defend an action of unlawful

detainer by showing that his rental property was being

taken from him solely on account of his color. Article I,

Section 26, however, would deprive the Negro defendant of

his defense on the g'round that the landlord may decline

to rent on any ground he chooses. Thus, the California

courts would be required to strike the defense in a repeti

tion of the Abstract Investment case. Plainly, if the Fed

eral Constitution bars the state courts from enforcing evic

tion on racial grounds, as held in Abstract Investment, and

the new amendment to the State Constitution prohibits the

judiciary from preventing such an eviction, the Federal

Constitution and Article I, Section 26 are at war.

It is simply not true that the new amendment merely

places the state in a neutral position—neither encourag-

29

mg nor discouraging racial discrimination. The enact

ment of an affirmative state policy banning state interfer

ence with landowners who discriminate against racial mi

norities cannot he equated with the absence of statutory

law relating to discrimination.

Unlike the situation that would exist if present fair

housing legislation were merely repealed, the new amend

ment (1) prevents the development of common law judicial

remedies against private acts of racial discrimination, (2)

precludes future State and local legislative action against

private acts of racial discrimination, no matter how moder

ate the action or how pressing its need, and (3) enshrines

in the California Constitution the grant of an “ absolute”

right in owners of real property to discriminate on racial

and religious grounds. This we submit is not ‘ ‘ neutrality. ’ ’

It constitutes action of the State directly sanctioning, en

couraging and empowering private acts of racial discrimi

nation. There is, in fact, a difference in bind between state

failure to prohibit private acts of racial discrimination (no

fair housing legislation) and amendment of a state con

stitution making private acts of racial discrimination a pro

tected “ right.” In the former instance, private acts of

racial discrimination are, to be sure, not prevented by legis

lation, but in the latter instance, they are actually en

couraged and empowered by the State.

The new amendment on its face tends to encourage ra

cial discrimination in housing on the part of those who de

sire to engage in it. As observed in Barrows v. Jackson,

346 U. S. 249, 254 (1953), there is unconstitutional encour

agement of the practice of writing racially restrictive cove-

30

nants when the state places “ its sanction behind the [dis

criminatory] covenants.” Enactment of a constitntional

provision placing acts of discrimination by all those who

own real property beyond the reach of the state courts, the

State Legislature and every governmental agency in the

state encourages discrimination in housing just as surely

as placing race labels on the ballot “ require [s] or encour

age [s] ” discrimination in voting. Anderson v. Martin, 375

U. S. 399, 402 (1964). In neither case is discrimination

compelled by the state; in both, it is at least facilitated.

This is not “ neutrality.” By adding Article I, Section 26

to its constitution, the state has placed its thumb on the

scale and tipped it in favor of discrimination.

The encouragement and assistance which the new amend

ment affords to discrimination becomes even clearer upon

consideration of the background events which led to its

adoption. The measure was sponsored by the California

Beal Estate Association and the California Apartment

Owners Association, and it was made clear during the ef

forts to obtain signatures on the initiative petition that the

proposal was intended to nullify the Bumford Act and other

fair housing laws.35 The official ballot argument in favor

of the measure disclosed the same purpose.36 It is of course

general public knowledge that the campaign respecting the

proposed amendment was principally concerned with the

issue of racial discrimination. In short, the purpose and

35. See, for example, Editorial in Vol. X L IV , Issue No. 2 of

California Real Estate Magazine (Dec. 1963), the official publication

of the California Real Estate Association.

36. The argument asserted that “ Under the Rumford Act, any

person refused by a property owner may charge discrimination.” It

urged voters to enact the proposed amendment in order to free prop

erty owners of any such charges.

31

expected effect of the measure was to free property owners

from legal restrictions against discriminatory practices in

housing. Indeed, racial considerations in the transfer of

property constituted the only matters in controversy in

respect to the amendment; neither proponents nor op

ponents were in disagreement as to other considerations

that might motivate a landowner to decline an offer to buy

or rent, and there was no occasion to propose legislation

in this respect.

In light of this single-minded purpose of the new amend

ment, its constitutionality need not be evaluated in terms of

its language alone. State laws or actions which seem neu

tral when considered in a vacuum are the equivalent of un

constitutional discriminatory state action where, as in the

present case, it can be shown by reference to surrounding

circumstances that the purpose and necessary effect is to

bring about racial or religious discrimination. For exam

ple, in Griffin v. School Board, 377 U. S. 218 (1964), the

State of Virginia closed its public schools in one county but

continued to operate its public school system in the other

counties. This Court found it unnecessary to consider

whether the state had authority to close its schools for law

ful reasons since it concluded, on the basis of external cir

cumstances surrounding the closing, that that was not the

case. As the Court stated (377 U. S. at 231):

(The) public schools were closed and private

schools operated in their place with state and county

assistance, for one reason, and one reason only, (to

discriminate against Negro children). (Emphasis

added.)

In the light of this motivation, the state action took on an

unconstitutional aspect.

32

To the same effect,, see Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U. S.

52 (1964), where the circumstances surrounding a state re

apportionment act were inquired into for the purpose of

ascertaining whether the districts were composed “ with

racial considerations in mind.” See also, Guinn v. United

States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915); Lane v. Wilson, 307 TJ. S. 268

(1939); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960).

The external evidence relating to the enactment of the

new amendment inescapably leads to the conclusion that it

was conceived, prepared, submitted for signatures, pre

sented to the voters and enacted with a single purpose in

mind—emasculating fair housing legislation and immuniz

ing discriminatory landowners against state regulation.

In these circumstances, it cannot be validly argued that the

new amendment does not constitute state encouragement of

racial discrimination. Property owners have been told in

effect that the state law stands behind any refusal by them

to sell or rent to Negroes or members of other minority

groups. And this is indeed the case. If the new amendment

is allowed to stand, no statutory or common law remedy

will be available under state law against racial discrimina

tion in housing sales and rentals. The Fourteenth Amend

ment, however, does not permit state involvement of this

character in discrimination of so invidious a nature. For

that reason alone, the amendment cannot stand.

D. Article I, Section 26 violates the Equal

Protection Clause because it authorizes

and facilitates racial zoning.

Fifty years ago, this Court held that the Fourteenth

Amendment bars state and local legislation dividing resi

dential areas into ‘ ‘ white ’ ’ and ‘ ‘ colored ’ ’ zones. Buchanan

33

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917); see also, Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U. S. 668 (1927); Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704

(1930). Subsequently, in tlie Shelley case, supra, it barred

attainment of the same result through court enforcement of

privately initiated racial covenants. Article I, Section 26

has the effect of authorizing and sanctioning achievement

of racial zoning by organized and concerted, or at least

parallel, action by those who control the housing market.

The result of permitting discrimination by those who

sell or rent housing is not merely to sanction occasional re

fusals here and there of individual housing units. The

principal result, and the only one involved here,37 is to

sanction the imposition of “ whites only” barriers at the

entrances to apartment houses, suburban developments and

even entire towns. Particularly with the phenomenal

growth in the size of housing developments—both rental

and for sale—since World War II,38 the creation of whole

new towns by a single company has become commonplace.

Article I, Section 26 sanctions de facto racial zoning for

these areas.

The Buchanan case dealt with zoning at the block level.

Article I, (Section 26 would in effect permit racial zoning by

private owners from the block to the city level.

37. It should be remembered that the cases now before this Court

do not involve the sale or rental of single family homes but the rental

of apartments in multiple dwellings. Indeed, the California statutes

affected by Article I, Section 26 do not reach discrimination by

owner-occupants of single family homes. They apply only to the kind

of housing that is under the control of those to whom housing is a

business.

38. McEntire, Residence and Race (U . Cal. Press, 1960), pp.

176-177. See also “ Construction Reports— Sale of N ew ’One-Family

Homes,” Series C2S, Departments of Commerce and Housing and

Urban Development, jointly— C25-26 (1963), C25-27 (1964), C25-

65-13 (1965), page 1 of each report.

34

We submit that sucb de facto racial zoning cannot be

permitted on the theory that it is initiated by private action

and that the state does no more than facilitate it by permis

sive legislation. The structuring of communities is a gov

ernmental function—no different in constitutional signifi

cance from the control of voting which this Court protected

from discrimination by private parties in Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944). There, this Court said (at

664):

This grant to the people of the opportunity for

choice is not to be nullified by a State through casting

its electoral process in a form which permits a private

organization to practice racial discrimination in the

election.

Here, it is the determination of occupancy patterns

which the state is permitting by “ casting its * * * [laws]

in a form which permits a private organization to practice

racial discrimination * * Here, as there, constitutional

significance should be denied “ so slight a change in form

* * *” (321 H. ,S, at 661).

Directly applicable here, we submit, is the line of argu

ment that controlled this Court’s decision in Marsh v. Ala

bama, 326 H. S. 501 (1946). There, it was held that the

Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of due process (in its

application to freedom of expression) protected the dis

tribution of literature on the streets of a privately-owned

company town. The Court first noted that such distribu

tion could not be barred by municipal action and then went

on to say (at p. 505):

35

* From these decisions it is clear that had the

people of Chickasaw owned all the homes, and all the

stores, and all the streets, and all the sidewalks, all

those owners together could not have set up a municipal

government with sufficient power to pass an ordinance

completely barring the distribution of religious litera

ture.

The Court held that the same results could not be

achieved by the action of a single owner, saying (at p. 506):

“ Ownership does not mean absolute dominion.” Referring

to the fact that the owner was acting as a private entity,

the Court said (at p. 507):

* * # Whether a corporation or a municipality owns

or possesses the town the public in either case has an

identical interest in the functioning of the community

in such manner that the channels of communication re

main free.

It concluded that the action of the state in effectuating the

restriction by prosecuting those who distributed the litera

ture violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Here, it is accepted that the state could not limit occu

pancy in any area to persons of one race. Yet it is claimed

that Article I, Section 26 can constitutionally permit own

ers of property to achieve the same result. We submit that

the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment cannot so

easily be evaded.

The concept that the state cannot be viewed as a neutral

party in the shaping of communities, and particularly the

racial aspect of communities, is buttressed here by the fact

that the state of California has never been neutral in this

matter. Whatever may be said about whether a state vio-

36

lates the Equal Protection Clause simply by baring a code

of law which, by its silence, permits but does not discourage

housing discrimination, that is not the case here. As shown

in the brief for respondents (pp. 11-13), California has, for

nearly a century, played an active role through its laws in

affecting the racial composition of residential areas. It

makes little difference that at times the state policy has

been to favor segregation and in others to curb it. The

essential fact is that California law has not been, “ neutral.”

It cannot now become “ neutral.”

E. The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a state from

disabling itself from fulfilling its constitutional

responsibility to assure equality in housing.

Even if it were assumed that the Fourteenth Amendment

imposes no obligation or responsibility on a state to enact

or maintain urgently needed fair housing legislation, it

would impose, we submit, at least the obligation to maintain

the availability of the police power of the state to act in

this area. In purporting to preclude exercise of that

remedial power by adopting Article I, Section 26, Cali

fornia has done what this Court has said it may not do in

the Second Slaughter House Case, Butchers’ Union Co. v.

Crescent City Co., I l l U. S. 746, 753 (1883):

No legislature can bargain away the public health

or the public morals. The people themselves cannot

do it, much less their servants. The supervision of

both these subjects of governmental power is continu

ing in its nature, and they are to be dealt with as the

special exigencies of the moment may require. Gov

ernment is organized with a view to their preservation,

and cannot devest (sic) itself of the power to provide

37

for them. For this purpose the legislative: discretion

is allowed, and the discretion cannot be parted with any

more than the power itself. (Emphasis added.)89

This is not to say that a state which has enacted fair

housing legislation may never repeal it. There may, of

course, be many situations in which the state could consti

tutionally repeal such legislation, such as when the Legisla

ture finds that the need no longer exists. Here, however,

the state has gone beyond repeal and has disabled itself

from carrying out a responsibility laid upon it by the Four

teenth Amendment. It has thereby “ parted with” the

“ legislative discretion” to deal with housing inequality

“ as the special exigencies of the moment may require.”

The Second Slaughter House case establishes that that may

not be done. 39

39. The unconstitutionality of the instant disablement is further

demonstrated by analogy to other illegal disablements of fundamental

power. For example a state canot disable its courts from hearing

and granting relief on federal causes of action. Testa v. Katt, 330