Rippy v Brown Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1956

28 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rippy v Brown Petition for Certiorari, 1956. cc369d80-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/760ff2fe-428f-45df-b3aa-bf676e70ddb2/rippy-v-brown-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

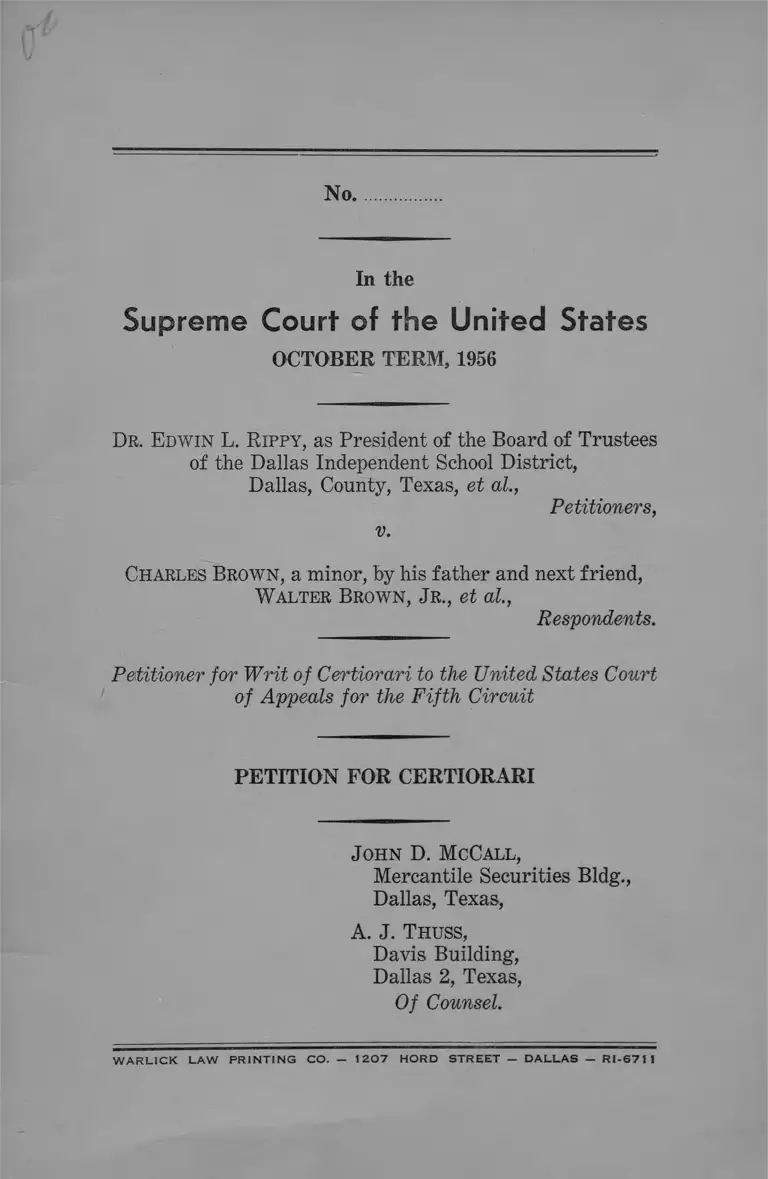

No.

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

Dr. Edwin L. Rippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District,

Dallas, County, Texas, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Charles Brown, a minor, by his father and next friend,

W alter Brown, Jr., et al.,

Respondents.

Petitioner for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

John D. McCall,

Mercantile Securities Bldg.,

Dallas, Texas,

A. J. Thuss,

Davis Building,

Dallas 2, Texas,

Of Counsel.

W A R L I C K L A W P R I N T I N G C O . — 1 2 0 7 H O R D S T R E E T — D A L L A S — R I - 6 7 I 1

I N D E X

Page

Reports of the Opinions of the Courts Below........... 3

Grounds on Which Jurisdiction Is Invoked............... 3

The Question Presented for Review............................ 3-4

Argument Amplifying the Reasons Relied on for the

Allowance of the Writ of Certiorari........................ 4-6

Conclusion ....................................................................... 6

Appendix A— Judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.............................. 7-8

Appendix B— Opinion..................................................... 9

Dissenting Opinion ..................................11-24

11 Citations

Page

Cases

Anniston Mfg. Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 337................. 6

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483............. 4-5

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294............. 4-5

Douglas v. Noble, 261 U. S. 165.................................... 6

U. S. v. Chemical Foundation, 271 U. S. 1................. 5-6

U. S. v. Clark, 20 Wall. 92............................................ 6

U. S. v. Nicks, 189 U. S. 199........................................ 6

U. S. v. Page, 137 U. S. 673.......................................... 6

Statutes

U. S. Code, Sec. 1254(1)................................................. 3

No.

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

Dr. Edwin L. Rippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District,

Dallas, County, Texas, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Charles Brown, a minor, by his father and next friend,

W alter Brown , Jr., et al.,

Respondents.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

Petitioners, DR. EDWIN L. RIPPY, AS PRESIDENT

OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE DALLAS

INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, DALLAS, DAL-

2

LAS COUNTY, TEXAS; W. A. BLAIR; ROBERT L.

DILLARD, JR.; ROBERT B. GILMORE; ROUSE HOW

ELL; (MRS.) VERNON D. INGRAM; VAN M. LAMM;

(MRS.) TRACY H. RUTHERFORD; FRANKLIN E.

SPAFFORD, DALLAS, DALLAS COUNTY, TEXAS, AS

MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE

DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, AND

DR. W. T. WHITE, AS SUPERINTENDENT OF PUB

LIC SCHOOLS OF THE DALLAS INDEPENDENT

SCHOOL DISTRICT; HOWARD A. ALLEN, AS PRIN

CIPAL OF THE W. H. ADAMSON HIGH SCHOOL;

J. H. GURLEY, AS PRINCIPAL OF THE MAPLE

LAWN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL; W. A. HAMILTON,

AS PRINCIPAL OF THE MIRABEAU B. LAMAR

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL; ELLA E. PARKER, AS

PRINCIPAL OF THE JOHN HENRY BROWN ELE

MENTARY SCHOOL; WILLIAM H. STANLEY, AS

PRINCIPAL OF THE THOMAS A. EDISON ELEMEN

TARY SCHOOL; RICHARD E. STROUD, AS PRINCI

PAL OF THE THOMAS J. RUSK JUNIOR HIGH

SCHOOL, AND, THE DALLAS INDEPENDENT

SCHOOL DISTRICT, pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue

to review the judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in CHARLES

BROWN, a minor, by his father and next friend, WAL

TER BROWN, JR., et ah, Appellants, versus DR. EDWIN

L. RIPPY, as President of the Board of Trustees of the

Dallas Independent School District, Dallas County, Texas,

et ah, Appellees, May 25, 1956.

3

(a)

OPINIONS DELIVERED IN THE COURT BELOW

The Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit is reported in ..... Fed. 2d ..... , and is

printed in Appendix B hereto, infra pages 9-24; Transcript

of Record, page 77. The Dissenting Opinion is presented

in Appendix B hereto, infra pages 11-24; Transcript of

Record, page 79,

(b)

GROUNDS ON WHICH JURISDICTION IS INVOKED

(I) The judgment of the court below was rendered May-

25, 1956, Transcript of Record, page 93.

(II) Petition for rehearing was denied June 19, 1956,

dissent noted, no opinion rendered.

(III) Jurisdiction of this Court to issue Writ of Cer

tiorari is invoked under 28 U. S. C. Section 1254(1).

(0

THE QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

The Court of Appeals erred in ordering the case back to

the trial court for further development of the facts regard

ing a program of desegregation.

The Record considered as a whole reflects that the Hon

orable District Judge correctly determined the suit was

prematurely filed and properly dismissed it without preju

dice to refiling, because the Trustees of the defendant

School District between May 31, 1955, when the Supreme

4

Court definitely outlined the duties of school trustees to

accomplish and change from segregated to a desegregated

system, and September 17, 1955, had not been given a

reasonable opportunity to exercise their discretion as to

the manner of accomplishing the drastic change in the

school plan of education.

ARGUMENT AMPLIFYING THE REASONS RELIED

ON FOR THE ALLOWANCE OF THE WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

The suit filed September 12, 1955, by Respondents,

sought mandatory injunctive relief which, if granted, would

have the effect of admitting negro scholastics to segregated

white schools immediately, and also prayed for declaratory

judgment that segregation as practiced in Texas was un

constitutional and void. That part of the complaint devoted

to a request for a hearing before a three-judge court and

a declaratory judgment was properly ignored. There was

no constitutional or statutory question involved as the law

in this respect on segregation had been declared as clearly

as English language could do so in

Brown v. Board of Education, 3J+7 U. S. b83;

Brown v. Board of Education, 31*9 U. S. 29b.

At the time the suit was filed there was nothing for the

trial court to decide. The law had been announced as to the

constitutional principles involved and further the District

Trustees were given time to exercise their discretion as to

how desegregation should be accomplished.

5

The answers filed by Petitioner in the trial court recog

nized its responsibilities of law with reference to desegre

gation and explained in detail the problems involved. The

pleadings of the Petitioner indicated affirmatively that

they were performing their administrative functions in

good faith.

The trial court, taking judicial knowledge of the hereto

fore traditional status of segregation in Texas, which

status had been accepted by State and Federal courts until

May 17, 1954, the date of the first decision in Brown, et al.

v. Board of Education, 31+7 U. S. b83, and further taking

into account it was not until May 31, 1955, when the

Supreme Court announced a more definite procedure for

future conduct in Brown v. Board of Education, 3J,9 U. S.

294., must have adhered to the accepted equitable principles

that a court should not accept and exercise jurisdiction

only when it is made clearly to appear that the school

officials are not performing their administrative functions

in good faith.

It is inherent in the majority opinion of the Court of

Appeals, though not specifically stated, that it could be

assumed the school officials would not follow the law. The

courts are in unique harmony in holding that it m il be

presumed that State officials have been following the law

or will do so.

Stated somewhat differently, a presumption of regular

ity supports official acts of public officers absent clear

evidence to the contrary. U. S. v. Chemical Foundation,

6

272 U. S. 1; U. S. v. Clark, 20 Wall. 92; U. S. v. Page, 137

V. S. 673; U. S. v. Nicks, 189 U. S. 199.

The officers of the Dallas Independent School District

having had such a short time to formulate a realistic pro

gram, and the answer evidencing an honest and realistic

intent to follow the last mandate of the Supreme Court, it

must be assumed that these administrative officers were

acting in a lawful manner based upon the facts evident to

them. Anniston Mfg. Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 337. In the

light of these facts, evident to the Board, it will not be

presumed they will act arbitrarily or unreasonably. Doug

las v. Noble, 261 U. S. 165.

The trial court, having recognized these fundamental

principles of law, properly dismissed the case as having

been prematurely filed without prejudice to refiling it at

a later date. The Honorable Court of Appeals of the United

States for the Fifth Circuit fell into error in not affirming

the decision.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

John D. McCall,

Mercantile Securities Bldg.,

Dallas, Texas,

Counsel of Record for Petitioner.

A. J. T huss,

Davis Building,

Dallas 2, Texas,

Of Counsel.

7

APPENDIX A

JUDGMENT OF THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Extract from the Minutes of May 25, 1956

No. 15,872

Charles Brown, a minor, by his father and next friend,

W alter Brown, Jr., et al.,

v.

Dr. Edwin L. Rippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District,

Dallas, County, Texas, et al.,

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas, and was argued by counsel;

On consideration whereof, It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said Dis

trict Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby, vacated

and reversed; and that this cause be, and it is hereby,

remanded to the said District Court with directions to

afford the parties a full hearing on the issues tendered in

their pleadings;

It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellees, Dr.

Edwin L. Rippy, as President of the Board of Trustees of

the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas County,

8

Texas, and others, be condemned, in solido, to pay the costs

of this cause in this Court for which execution may be

issued out of the said District Court.

“ Cameron, Circuit Judge, dissenting.”

9

APPENDIX B

In the

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 15,872

Charles Brown, a minor, by his father and next friend,

W alter Brown, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

Dr. Edwin L. Rippy, as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District,

Dallas, County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas

(May 25, 1956.)

Before HUTCHESON, Chief Judge, and CAMERON and

BROWN, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM: The suit was brought by negro children

of school age against the President and members of the

Board of Trustees of the Dallas Independent School Dis

trict and others for a declaratory judgment and an injunc

10

tion. It had for its object the entry of a judgment requiring

the defendants to desegregate with all deliberate speed the

schools under their jurisdiction, and to cease their prac

tices of segregating plaintiffs in elementary and high

school education on account of race and color.

The claim was that the defendants, though obligated to

do so, were conspiring to neglect to proceed as required

by law.

The defendants denied that they were proceeding or pro

posing and conspiring to proceed, in violation of law, to

force segregation upon plaintiffs on account of their race

and color. Alleging in effect that they were proceeding,

and would continue, as required in and by the decisions of

the Supreme Court, to proceed with all deliberate speed

with the change over from segregated to non-segregated

schools, they prayed that all relief, declaratory and injunc

tive, be denied.

When the case was called, instead of a hearing on

evidence or agreed facts, there was a running colloquy

between judge and counsel, in which, after admitting that

at least some of the plaintiffs had sought and been denied

admission on a non-segregated basis, the defendants’ coun

sel vainly tried to offer, in explanation and support of

their action, evidence of the matters pleaded by them.

Declining to hear the evidence, apparently under the

mistaken view that the plaintiffs had agreed to the facts

pleaded by defendants, though the record showed the exact

contrary, the district judge, determining that the suit was

11

premature, denied the injunction prayed and ordered the

suit dismissed without prejudice to the right of plaintiffs

to file it at some later date.

Appealing from that order plaintiffs are here insisting

that the record shows that the judgment was entered under

a complete misapprehension both of the law and of the

facts and must be reversed.

The defendants here urging that the action of the court

responded to the facts as shown of record and to the law

as declared in the decisions of the Supreme Court, insist

that the suit was premature and was properly dismissed

without prejudice.

We think it quite clear that there is no basis in the evi

dence for the action taken by the district judge, none in

law for the reasons given by him in support of his action.

The judgment is accordingly VACATED and REVERSED

and the cause is REMANDED with directions to afford

the parties a full hearing on the issues tendered in their

pleadings.

CAMERON, Circuit Judge, Dissenting:

I.

The Court below stated, as one of its reasons for dis

missing the complaint without prejudice, the following:1

“The direction from the Supreme Court of the

United States requires that the officers and principals

Ut mentioned other grounds arguendo hut this is the basic finding.

12

of each institution, and the lower Courts, shall do

away with segregation after having worked out a

proper plan. That direction does not mean that a long

time shall expire before that plan is agreed upon. It

may be that the plan contemplates action by the state

legislature. It is not for this Court to say, other than

what has been said by the Supreme Court in that

decision.

“ To grant an injunction in this case would be to

ignore the equities that present themselves for recog

nition and to determine what the Supreme Court itself

decided not to determine. Therefore, I think it appro

priate that this case be dismissed without prejudice

to refile it at some later date. Give them some time to

see what they can work out, and then we will pass

upon that equity.” [Emphasis supplied.]

The Court below was evidently referring to what the

Supreme Court said in its two segregation decisions: “ Be

cause these are class actions, because of the wide applic

ability of this decision, and because of the great variety of

local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases

presents problems of considerable complexity. * * *.” 2

“ Full implementation of these constitutional principles

may require solution of varied local school problems. School

authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidat

ing, assessing and solving these problems; courts will have

to consider whether the action of school authorities consti

tutes good faith implementation of the governing constitu

tional principles. * * * At stake is the personal interest

of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as

2Brown, et al. v. Board of Education, etc., May 17, 1954, 347 U. S.

483, 495.

13

practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate

this interest may call for elimination of a variety of obsta

cles in making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth in

our May 17, 1954, decision. Courts of equity may properly

take into account the public interest in the elimination of

such obstacles in a systematic and effective manner. * * *

To that end the courts may consider problems relating to

administration, arising from the physical condition of the

school plant, the school transportation system, personnel,

revision of school districts and attendance areas into com

pact units to achieve a system of determining admission to

the public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local

laws and regulations which may be necessary in solving

the foregoing problems. * * *.” (Emphasis added.)3

In my opinion, the Court below was justified in using its

discretion to dismiss this action without prejudice on the

ground that it was prematurely brought. It seems clear

that the course of action fixed by the Supreme Court con

templated that school boards and other state officials should

take hold of the complex problem and work it out with the

aid and in the light of their superior knowledge of the

problem in all of its ramifications. These state officials

were to work in an administrative capacity under the plans

detailed in these two opinions. The Supreme Court recog

nized that the problem should be viewed as a whole and

that time would be required and that the state authorities

3Brown, et al. v. Board of Education, etc., May 31, 1955, 349 U. S.

294, 299-301.

14

should be given full primary responsibility, as well as

authority, to solve the problem in the light of local condi

tions. As long as these officials were proceeding in good

faith and with deliberate speed to do this, it is clear to me

that the Supreme Court did not intend that they should be

subjected to harassment by vexatious suits or by the inter

vention of the courts. It was the “ action of the school

authorities” which courts were to pass upon at the proper

time and after there had been opportunity for such action.

The scheme did not contemplate that the courts should

anticipate or seek to control such action or should impede

it by too close chaperonage. “ Action” is defined as “ an act

or thing done,”— i.e. already performed.

The principles controlling such a situation were an

nounced in a recent decision of the Supreme Court in a

situation not unlike that with which we are here dealing.4

That case involved the question whether judicial action

would be taken to arrest the functioning of the First and

Second Renegotiation Acts on constitutional grounds before

administrative remedies had been exhausted. The Supreme

Court held that such a short-circuiting of the administra

tive remedy would be “ a long overreaching of equity’s

strong arm,” and used this language in reaching that con

clusion :

“ The doctrine, [exhaustion of administrative rem

edy] wherever applicable, does not require merely the

initiation of prescribed administrative procedures. It

-•Aircraft and Diesel Equipment Corp. v. Hirsch, et al., 1947, 331 U. S.

752, 767.

15

is one of exhausting them, that is, of pursuing them

to their appropriate conclusion and, correlatively, of

awaiting their final outcome before seeking judicial

intervention. The very purpose of providing either an

exclusive or an initial and 'preliminary administrative

determination is to secure the administrative judg

ment either, in the one case, in substitution for judi

cial decision or, in the other as foundation for or per

chance to make unnecessary later judicial proceed

ings. Where Congress [here the Supreme Court] has

clearly commanded that administrative judgment be

taken initially or exclusively, the courts have no law

ful function to anticipate the administrative decision

with their own, whether or not when it has been ren

dered they may intervene. * * * To do this not only

would contravene the will of Congress as a matter of

restricting or deferring judicial action. It would null

ify the congressional objects in providing the admin

istrative determination.” [Emphasis added.]

Again, in Myers v. Bethlehem Corp.,5 Mr. Justice Bran-

deis, citing a score of cases, stated: “ The contention is at

war with the long settled rule of judicial administration

that no one is entitled to judicial relief for a supposed or

threatened injury until the prescribed administrative

remedies have been exhasted. * * * Obviously, the rule

requiring exhaustion of the administrative remedy cannot

be circumvented by asserting that the charge on which the

complaint rests is groundless and that the mere holding

of the prescribed administrative hearing would result in

irreparable damage. Lawsuits also often prove to have been

groundless; but no way has been discovered of relieving the

51938, 303 U. S. 41, 50-51.

16

defendant from the necessity of a trial to establish the

fact.” 6

And this Court has applied the principle in a series of

cases involving claims under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The first of these was Cook, et al. v. Davis, 19U9,178 F. 2d

595, cert. den. SiO U. S. 811. A District Court in Georgia

had intervened by injunction in favor of Davis, who claimed

that he was discriminated against as a Negro teacher. This

Court wrote an exhaustive opinion in reversing that deci

sion and used this language:

“ The broad principle that administrative remedies

ought to be exhausted before applying to a court for

extraordinary relief, and especially where the federal

power impinges on State activities under our federal

system, applies to this case. ‘No one is entitled to

judicial relief for a supposed or threatened injury un

til the prescribed administrative remedy has been

exhausted.’ Myers v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp.,

303 U. S. 41, citing many cases relating to relief by

injunction. We held in Bradley Lumber Co. v. Na

tional Labor Relations Board, 5 Cir., 84 F. 2d 97,

that the same principle applies to relief by declaratory

decree. ‘The rule that a suitor must exhaust his ad

ministrative remedies before seeking the extraordi

nary relief of a court of equity (citing many cases), is

of special force when resort is had to the federal courts

to restrain the action of state officers.’ * * *.” 7

6And see also Alabama Public Service Commission, et al. v. Southern

Railway Co., 1951, 341 U. S. 341, 349-50.

7And see Bates, et al. v. Batte, et al., 5 Cir., 1951, 187 F. 2d 142, 144.

And we applied the rule as “of special importance between the federal

courts and state functionaries” when we denied equitable relief to

Negroes seeking voting rights in Peay, et al. v. Cox, Registrar, 5 Cir.,

1951, 190 F. 2d 123, 125, Cert. den. 32 U. S. 896.

17

II.

The situation before the Court below furnishes an excel

lent illustration of the wisdom and relative necessity of

permitting the school authorities to apply their experience,

judgment and investigative facilities to the solution of the

problem. Dallas County has one hundred twenty school

buildings, housing for instruction 78,691 white children

and 14,593 Negro children. Each of those schools and each

of the children presents a separate problem to be dealt with

in the light of many other considerations besides race. It

is not humanly possible that the District Courts consider

and resolve those problems in all of their details and

intricacies.

The Northern District, in which Dallas County is situ

ated, has ninety-nine other counties whose legal business

must be handled by three active District Judges. If the

Court below is to be compelled to take jurisdiction of this

action and try it, there is no reason why every other school

child in Dallas County and in the Northern District of

Texas, both white and Negro, should not file suit and

demand a hearing and procure an adjudication of his own

individual problems.

III.

Under accepted equitable principles a court should accept

and exercise jurisdiction only when it is made clearly to

appear from the pleadings that the school officials are not

performing their administrative functions in good faith.

18

The complaint here fails entirely to charge any facts tend

ing to sustain such a thesis and the answer refutes it com

pletely. The Court will presume that the state officials are

acting honestly and that they will expeditiously give plain

tiffs all relief to which they are entitled. Davis v. Am ,

5 Cir., 1952, 199 F. 2d l>2i.

The complaint alleges that the twenty-seven plaintiffs on

September 5, 1955, applied for admission to certain schools

in Dallas Independent School District: one applied to a

junior high school; eight applied to a high school; and the

residue applied to four separate elementary schools. In

each instance it is alleged that the principal of the school

conspired with the superintendent of public schools to

deprive plaintiffs of the right immediately to attend the

specified schools based upon their race and color.

The complaint contains no charge at all that the school

officials did not act in good faith in denying them such

immediate entry or that the facts did not justify such

denial. The complaint prayed for a declaratory judgment

declaring the statutes of the State of Texas under which

defendants assumed to act unconstitutional, and defining

the legal rights and relations of the parties; and for injunc

tion, both temporary and permanent against any enforce

ment by the defendants of the Texas Statutes referred to.

The answer contains this statement:

“ * * * Defendants deny there is any scheme or conspir

acy to circumvent or evade the law or to deprive any child,

student or other person of their civil rights. The principals

19

of the various schools were following the instructions is

sued to them by the administrative staff. The administra

tive staff and the district trustees are now and have been

making an honest, bona fide, realistic study of the facts

to meet the obligations the law has placed upon them to

provide adequate public school education and to perfect, as

soon as possible, a workable integrated system of public

education.”

It was further shown from the sworn answer and the

stipulations of counsel that the Dallas Public School Sys

tem has operated for ninety years as a segregated system

and that budget procedures looking to the raising of funds

by taxation had been formulated and bonds issued on that

basis and upon the enumeration of white and Negro stu

dents already made. The details of the budget are controlled

by state laws and practices, and thereunder statistical data

is gathered in January of each year. The budget for the

school year had reached an advanced state of preparation

when the Supreme Court decision was published on the last

day of May, 1955, and it was impossible to make the neces

sary adjustments and allocations of students and teachers

by the beginning of the school year in September, 1955.

In order that all might be advised of this, the superin

tendent of schools issued a statement on July 13, 1955,

advising that a detailed study of all of the problems inher

ent in desegregating was in progress and the details of that

study were set forth. Thirty-five million dollars in bonds

had recently been issued and the capital improvements

20

involved therein would have to be changed. Sixty per cent

of the money for operating the Dallas schools came from

the State of Texas, and the Attorney General had ruled

that funds could be allocated for the coming year only on

the segregated basis existing when appropriations were

made and plans for the school year set in motion. Complete

chaos and a complete breakdown in public school education

for both White and Negro students would result if the

school officials should undertake a haphazard effort to deal

specially with isolated individuals and the six schools in

volved in the suit out of the total of one hundred twenty.

The situation required an over-all adjustment based upon

a consideration of the entire school system, and granting

to all individuals and classes the rights spelled out in the

Supreme Court decisions.

IV.

These facts were known to the plaintiffs and their attor

neys when, they applied for admission to the six schools

mentioned, and when, one week thereafter, this civil action

was begun. Anyone willing to accept facts would know that

the relief demanded in the suit could not be afforded in so

short a time. That relief was threefold. (1) A judgment

was sought declaring the Texas Statutes unconstitutional.

These statutes have been declared unconstitutional by the

Supreme Court of Texas and defendants’ do not take issue

with the averments of the complaint in this regard and

nothing is presented for the Court to decide. (2) Plaintiffs

prayed that the rights of the parties be declared. There

was no controversy between the litigants as to their respec

21

tive rights. Plaintiffs claimed the right to be admitted to

schools without discrimination because of race or color.

The defendants freely admitted that right. The only point

at issue related to timing. There was no “ actual contro

versy” between the parties, and, therefore, no jurisdiction

was conferred on the Court by 28 U. S. C. A. 2201 and Rule

57 F. R. C. P. (3) Injunctions, preliminary and perma

nent, were sought. There was no threat by the defendants

to do anything plaintiffs did not want done or to omit

doing anything plaintiffs wanted done. Defendants sol

emnly declared their readiness to admit plaintiffs to schools

on an integrated basis when the problem could properly be

worked out. The very basis of injunctive relief is threat

ened action or failure to act by one party in derogation of

established rights of the other party. The rights claimed by

the plaintiff are admitted and neither the pleadings nor

the proof reflect any threat by the defendants to violate

those rights. Therefore, there is no basis for injunctive

relief.

“ The history of equity jurisdiction is the history of

regard for public consequences in employing the extraordi

nary remedy of the injunction. There have been as many

and as variegated applications of this supple principle as

the situations that have brought it to play. * * *. Few

public interests have a higher claim upon the discretion of

a federal chancellor than the avoidance of needless friction

with state policies, whether the policy relates to the en

forcement of the criminal law * * * or the final authority

of a state court to interpret doubtful regulatory laws of

22

the state * * *. These cases reflect a doctrine of absention

appropriate to our federal system whereby the federal

courts, ‘exercising a wise discretion’ restrain their author

ity because of ‘scrupulous regard for the rightful inde

pendence of the state governments’ and for the smooth

working of the federal judiciary. * * *. This use of equit

able powers is a contribution of the courts in furthering

the harmonious relation between state and federal author

ity without the need of rigorous congressional restriction

of those powers * * *.” 8

Y .

The majority opinion reverses the judgment dismissing

the complaint without prejudice and orders the Court below

to “ afford the parties full hearing on the issues tendered

in their pleadings.” 9 To permit judicial proceedings to be

8Railroad Commission of Texas, et al. v. Pullman Company, et al.,

1941, 312 U. S. 496, 500-1, and see also Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319

U. S. 315, 332-3; Reliable Transfer Co. v. Blanchard, 5 Cir., 1944, 145

F. 2d 551, 552.

9Plaintiffs aver in their complaint that they are entitled to have it

heard by a three-judge court under 28 U. S. C. A. 2281, et seq., and pray

that such a court be convened. If the hearing ordered by the majority

is to be held, it is my opinion that these statutes must be followed, and

that any injunction which might possibly be ordered by one judge would

be void for want of jurisdiction. The statute provides: “ An interlocu

tory or permanent injunction restraining the enforcement, operation or

execution of any State statute by restraining the action of any officer

of such State in the enforcement or execution of such statute or of an

order made by an administrative board or commission acting under

State statutes, shall not be granted by any district court or judge there

of upon the ground of the unconstitutionality of such statute unless the

application therefor is heard and determined by a district court of three

judges under Section 2284 of this title.” The complaint specifically avers

that the defendants are so acting under state statutes and the language

of 2281 fits the situation exactly. Although such practices are much in

vogue, I do not share the belief that specific congressional provisions

can be repealed or circumvented by judicial fiat.

See Board of Supervisors, etc. v. Tureaud, Oct., 1955, 226 F. 2d 714,

and my dissents in the same case reported in 225 F. 2d at 435, Aug. 23,

1955, and 228 F. 2d at 896, Jan., 1956.

23

in progress while the school authorities are seeking to

perform duties defined by the Supreme Court as primary

is not only to provide duplication of effort and to bring the

two proceedings into inevitable conflict, but it is to cast

into confusion a scheme which the Supreme Court spelled

out with clarity. Particularly is this true where, as here,

it is perfectly plain that the school authorities have not

had time to study the complexities of the problem and to

come up with the proper answers.

It is not reasonable that the Supreme Court would have

placed primary responsibility in a group commissioned to

act administratively with the expectation that this group

would be hampered or vexed in accomplishing their task,

severely difficult at best, by contemporaneous litigation

directed towards fashioning a club to be held over their

heads. Such a judicial intervention would connote a dis

trust of the functioning of the preliminary administrative

process and would cast those conducting it under a handi

cap of suspicion so great as to thwart at the threshold the

orderly carrying out of the procedures so plainly delineated

by the Supreme Court.

Moreover, that course would, in my opinion, contravene

the principles and policies so carefully worked out by this

Court in Cook v. Davis, supra, and the other cases follow

ing it; and would repudiate the approval we gave to the

action of the trial Court in Davis v. Am, supra, where the

24

complaint had been dismissed as premature, and the lan

guage we there used (p. 425):

“We cannot assume that if plaintiffs had pursued

that remedy they would have been denied the relief to

which they were entitled. The presumption is the other

way. As the complaint does not allege that plaintiffs

have availed themselves of the state administrative

remedies open to them under the Act, their resort to a

federal court to control state officers in the perform

ance of their duties is premature.” [Emphasis added.]

It is my opinion that it was within the competence of the

Court below to dismiss without prejudice his prematurely

brought complaint and that, in doing so, it followed the

spirit and letter of the Supreme Court’s opinions and also

vindicated the true function of the judicial process. I would

affirm.

A True Copy:

Teste:

(SEAL)

John A. Feehan , Jr.

Cleric of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

W A K I I C K