Bushey v The New York State Civil Service Commission Reply Brief of Defendant-Intervenor-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1985

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bushey v The New York State Civil Service Commission Reply Brief of Defendant-Intervenor-Appellant, 1985. 15601531-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76353041-ae8f-44ab-897b-df6ddd449848/bushey-v-the-new-york-state-civil-service-commission-reply-brief-of-defendant-intervenor-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

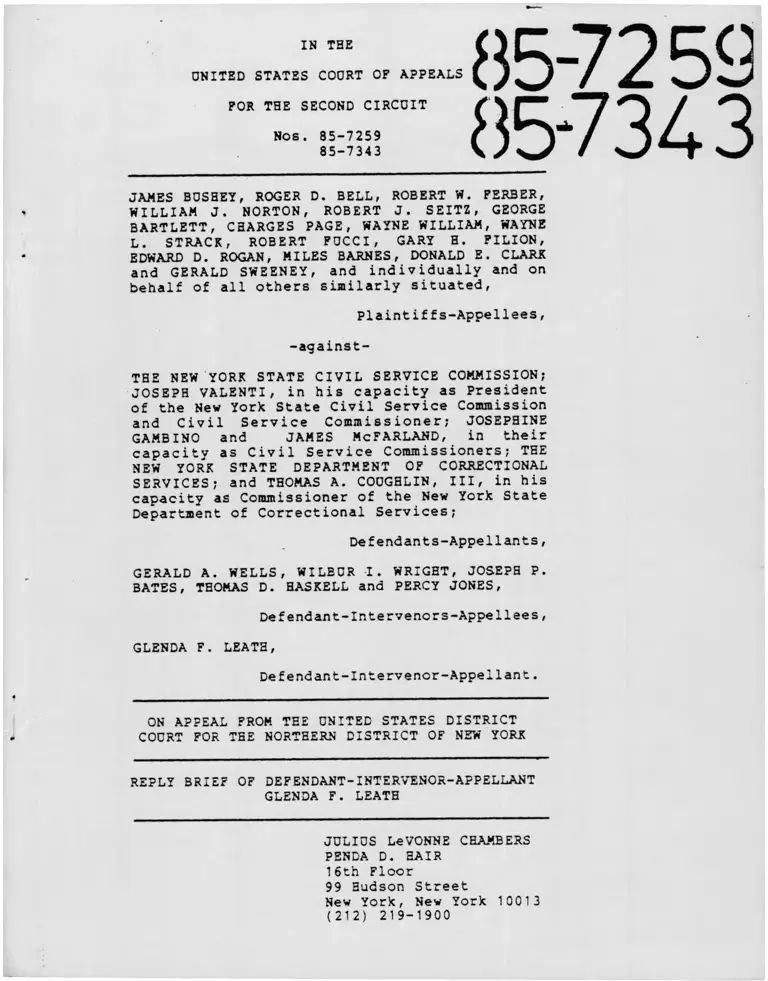

IN THE

UNITED STATES COORT OF APPEALS

POR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-7259

85-7343 85-73A 3

JANES BUSHEY, ROGER D. BELL, ROBERT W. FERBER,

WILLIAM J. NORTON, ROBERT J. SEITZ, GEORGE

BARTLETT, CHARGES PAGE, WAYNE WILLIAM, WAYNE

L. STRACK, ROBERT FUCCI, GARY H. PILION,

EDWARD D. ROGAN, MILES BARNES, DONALD E. CLARK

and GERALD SWEENEY, and individually and on

behalf of all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

THE NEW YORK STATE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION;

JOSEPH VALENTI, in his capacity as President

of the New York State Civil Service Commission

and Civil Service Commissioner; JOSEPHINE

GAMBINO and JAMES McFARLAND, in their

capacity as Civil Service Commissioners; THE

NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL

SERVICES; and THOMAS A. COUGHLIN, III, in his

capacity as Commissioner of the New York State

Department of Correctional Services;

Defendants-Appellants,

GERALD A. WELLS, WILBUR I. WRIGHT, JOSEPH P.

BATES, THOMAS D. HASKELL and PERCY JONES,

Defendant-Intervenors-Appellees,

GLENDA F. LEATH,

Defendant-Intervener-Appellant.

ON APPEAL FROM TEE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

REPLY BRIEF OF DEPENDANT-INTERVENOR-APPELLANT

GLENDA F. LEATH

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

PENDA D. HAIR

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.

II.

III.

Page

NEITHER PLAINTIFFS NOR THE WELLS INTERVENORS HAVE

POINTED TO ANY LEGAL BASIS OR AUTHORITY FOR

CONCLUDING THAT THEY WILL SUCCEED IN OBTAINING

PERMANENT INJUNCTIVE RELIEF 2

THE NORTHERN DISTRICT'S FINDING OF IRREPARABLE

HARM IS CLEARLY ERRONEOUS 6

THE KIRKLAND CONSENT ORDER REQUIRES USE OF THE

KIRKLAND LIST TO FILL ALL VACANCIES EXISTING ON

THE DATE THE KIRKLAND LIST WAS PUBLISHED 8

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Bell & Howell: Mamiya Co. v. Masel Supply Co., 6

719 F . 2d 42 (2d Cir. 1 983 )

Bushey v. New York State Civil Serv. Comm'n , 571 F. Supp. 4,7

1562 (N.D.N.Y. 1983), rev'd , 733 F .2d 220 (1984),

cert, denied, 53 U.S.L.W. 3477 (Jan. 3, 1985)

Guardians Ass'n of New York City v. Civil Service Comm1n , 9,10

630 F .2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980), cert. denied,452 U.S.

940 (1981)

Pennhurst State School v. Halderman, 104 S. Ct. 900 (1984) 7

United States v. New York Telephone Co., 434 U.S. 159 (1977)* 7

Other Authorities:

All Writs Act, 28. U.S.C. § 1651 7

Fed. Rule Evid. 201 2

Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 11 5

Fed. Rule App. Proc. 10 2

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-7259

85-7343

JAMES BUSHEY, ROGER D. BELL, ROBERT W. FERBER,

WILLIAM J. NORTON, ROBERT J. SEITZ, GEORGE

BARTLETT, CHARGES PAGE, WAYNE WILLIAM, WAYNE

L. STRACK, ROBERT FUCCI, GARY H. FILION,

EDWARD D. ROGAN, MILES BARNES, DONALD E. CLARK

and GERALD SWEENEY, and individually and on

behalf of all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

-against-

THE NEW YORK STATE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION;

JOSEPH VALENTI, in his capacity as President

of the New York State Civil Service Commission

and Civil Service Commissioner; JOSEPHINE

GAMBINO and JAMES McFARLAND, in their

capacity as Civil Service Commissioners; THE

NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL

SERVICES; and THOMAS A. COUGHLIN, III, in his

capacity as Commissioner of the New York State

Department of Correctional Services;

Defendants-Appellants,

GERALD A. WELLS, WILBUR I. WRIGHT, JOSEPH P.

BATES, THOMAS D. HASKELL and PERCY JONES,

Defendant-Intervenors-Appellees,

GLENDA F. LEATH,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellant.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

REPLY BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-INTERVENOR-APPELLANT

GLENDA F. LEATH

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

All of the plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors had the

opportunity to compete for promotion under the 1983 selection

procedure that resulted in the Kirkland list. Furthermore,

neither plaintiffs nor the Wells intervenors contest that the

1933 procedure was carefully developed with outside professional

expert assistance and is a fair, job-related selection device.

Rather plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors ask the Court to

order appointments to be made on the basis of the earlier 1982

examination simply because of some of these 18 individuals scored

higher on the earlier test. In essense, the position of plain

tiffs and the Wells intervenors is that because defendants gave

an examination, defendants should be required to use the test

results, despite the fact that the test was hastily prepared,

cannot be shown to be job-related, and produced an extreme

adverse impact on those few minority candidates who were not

discriminatorily excluded from the candidate pool. There is

simply no legal basis for such a claim.

I.

NEITHER PLAINTIFFS NOR THE WELLS

INTERVENORS HAVE POINTED TO ANY

LEGAL BASIS OR AUTHORITY FOR

CONCLUDING THAT THEY WILL SUCCEED IN

OBTAINING PERMANENT INJUNCTIVE

RELIEF*

The merits of this case involve two issues: first, whether

* We note that all of the parties have stipulated that pages

33-47 of the Addendum to the Brief of Intervenor Leath are

properly part of the record in this case. That Stipulation has

been filed with the Northern District pursuant to Fed. Rule App.

Proc. 10(c). The Court may take judicial notice of the documents

from the Kirkland case, pages 1-32 of the Addendum. Fed. Rule

Evid 201.

2

the 1982 examination was scored properly and second, to what

injunctive relief, if any, the party that prevails on the first

issue will be entitled. The Northern District focused solely on

the first issue, concluding that one of two opposing parties must

prevail on the scoring issue. However, it is the second issue

that is of crucial importance in issuing a preliminary injunc

tion .

At a minimum, a preliminary injunction must relate to

permanent injunctive relief that the movant is likely to obtain.

Our opening brief discusses in detail why neither plaintiffs nor

the Wells intervenors have any chance of obtaining permanent

relief in the form of actual appointments to Captain's positions.

Plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors totally fail to address this

devastating reality. In fact, not once in either of their

lengthy briefs do plaintiffs or the Wells intervenors identify

any legal basis or authority on which the Northern District might

order their appointments at the close of this litigtion.

Plaintiffs' only reference to this question occurs on the

last page of their brief. They do not attempt to argue that the

District Court would be authorized to order their appointment.

Rather they state: " [E]ven if the District Court refused to

force the State to make appointments from the unadjusted 1982

Eligible List on subject matter jurisdiction grounds, the

plaintiffs would still be entitled to go to State court at the

3

conclusion of this action to enforce their rights under state law

requiring the State to make appo in tmen ts consistent with Civil

Service Law § 56." P1. Br. at 28. Plaintiffs apparently take

the ludicrous position that a federal court is authorized to

issue a preliminary injunction in order to preserve remedial

options in a State court suit that has not even been filed.

Clearly, this is not sufficient to establish a substantial

likelihood of obtaining injunctive relief and any such finding by

the Northern District would have constituted legal error and

1.

abuse of discretion.

Moreover, a State court would not be able to order appointments

that violate Title VII. Plaintiffs have not attempted to refute

the analysis in our opening brief demonstrating that appointments

from the unadjusted Bushey list would violate Title VII. In

addition, the State defendants disagree with plaintiffs' inter

pretation of state law. It certainly cannot be said that

plaintiffs have established a substantial likelihood that they

would prevail in State court if they were to commence such a

proceed ing .

Plaintiffs in their brief devote substantial effort in an attempt

to establish that their Fourteenth Amendment claim of intentional

discrimination is still alive despite their failure to appeal the

Northern District's finding that this claim is "not maintain

able," 571 F. Supp. at 1566-67 n.9. On the last page of their

brief, plaintiffs suggest that the Court could award back pay and

retroactive seniority if it found for Plaintiffs on this claim.

P1. Br . at 28. This argument does not help plaintiffs in the

defense of the preliminary injunction. First, if back pay and

retroactive seniority are appropriate remedies, they can be

awarded without enjoining appointments from the Kirkland list.

Second, if plaintiffs are arguing that their Fourteenth Amendment

claims serve as a basis for awarding them appointments, they have

not estblished a likelihood of success on this claim. The

Northern District Court has already ruled against them on this

issue and thus could not have based its injunction on a finding

that plaintiffs were likely to prevail on this claim.

Third, there is no legal authority under the Fourteenth Amendment

for awarding plaintiffs appointments, even if they were to

4

The Wells intervenors have even less to say on this point.

As noted in our opening brief, the Wells intervenors have

asserted no claim against the State defendants and thus cannot

possibly assert that they have a substantial likelihood of

prevailing on any claim. In response, the Wells intervenors note

that they have argued that they are entitled to relief and that a

2

motion to file a cross claim probably would be granted. Wells

Br. at 16, n . 1 1 . Of course, the speculative possibility of

relief on a cross claim that has not been filed and may never be

3

filed is not sufficient to establish a likelihood of success on

the merits. The Wells intervenors still have failed to identify

any legal basis for such a claim. This omission is glaring in

view of the discussion in our opening brief indicating that no

such basis exists. Since the Wells intervenors have not been

able to make any argument at all in support of such a claim, they

succeed on their constitutional claim.

To the contrary, counsel for the Wells intervenors conceded in

the Northern District that because such a claim had not been

filed, his clients would not be entitled to appointment if the

State defendants prevailed on the scoring issue. JA. 600.

There is a very real reason why the Wells intervenors may never

file such a cross claim. Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure requires that the attorney signing a pleading verify

that it is "warranted by existing law or a good faith argument

for the extension, modification or reversal of existing law." As

discussed in the text above and in our opening brief, there is no

possible legal basis for such a claim by the Wells intervenors

and thus their attorneys would be subject to Rule 11 sanctions if

they signed such a claim.

5

can hardly ask this Court to conclude that they have established

a likelihood of success on the claim.

II.

THE NORTHERN DISTRICT'S FINDING OF

IRREPARABLE HARM IS CLEARLY ERRO

NEOUS_________________________ _ _

Both plaintiffs and the Wells-intervenors devote most of

their briefs to the argument that because of the uniqueness of

Captain's positions, they would suffer irreparable injury in the

absence of the injunction. However, the Northern District made

no findings as to whether Captain's positions are unique or whether

any claimant would suffer work-related irreparable harm if the

injunction were not entered. The Northern District's only

finding of irreparable harm was erroneously based on the con

clusion that "plaintiffs stand to be irreparably injured by

losing their right to judicial review of their original claims."

4

JA. 891-92. Thus counsel's assertions concerning the uniqueness

of Captain's positions are irrelevant to the question whether the

Northern District acted properly in entering the preliminary

injunction. E . g , , Bell & Howell; Mamiya Co. v. Masel Supply

Co., 719 F .2d 42, 46 (2d Cir. 1983).

4 The only competent evidence on the issue of job-related harm is

that submitted by the State defendants, which showed that little,

if any, harm to the plaintiffs and Wells intervenors would result

if the injunction were denied. JA. 659-68.

6

As noted in our opening brief, the All Writs Act does not

authorize the entry of an injunction to prevent mootness, where

the moving party has received all the relief to which he or she

5

is entitled. The Wells intervenors apparently interpret the New

6

York Telephone case, which extended jurisdiction under the All

Writs Act to non-parties, to authorize district courts to issue

injunctions to prevent actions that properly moot a case. See

Wells Br. at 20. Such an interpretation would mean that a case

could become moot only where the affected parties failed to move

for a preliminary injunction. This would overrule our entire body

of mootness law.

Both plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors rely heavily on

the argument that the Northern District could prevent the State

defendants from mooting the lawsuit because defendants' failure

to use the Bushey list might contravene state law. However, the

federal courts are not empowered to adjudicate claims of viola-

The Wells intervenors assert that the reference to the All Writs

Act "buttresses" the Northern District's finding on irreparable

harm, Wells Br. at 20, implicitly conceding that the court's

reasoning on this point is not by itself sufficient to sustain

the preliminary injunction. Unfortunately for plaintiffs and the

Wells intervenors, there is nothing else to be buttressed. The

Court relied solely on the All Writs Act and the possible mooting

of plaintiffs' claims. JA. at 891-92.

United States v. New York Telephone Co., 434 U.S. 159 (1977).

7

tions of state law, Pennhurst v. State School v. Halderman , 104

S. Ct. 900 (1984), and this Court has already dismissed the

7

State law claims. 733 F . 2d at 223, n. 4.

III.

THE KIRKLAND CONSENT ORDER REQUIRES

USE OF THE KIRKLAND LIST TO FILL ALL

VACANCIES EXISTING ON THE DATE THE

KIRKLAND LIST WAS PUBLISHED_______

Plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors argue that the Bushey

list should be used to fill certain vacancies that arose before

publication of the Kirkland list. They contend that the Kirkland

Settlement Agreement contemplated some use of the Bushey list.

Plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors misstate the issue. The

question is not whether the Kirkland settlement allowed the

Kirkland defendants to make interim appointments while the new

selection procedure was being developed. The question is whether

the Kirkland settlement allowed the defendants to hold vacancies

open and then fill them from the Bushey list after the Kirkland

list was published. The Settlement Agreement clearly indicates

that such action is not permitted.

Under the Kirkland settlement, defendants retained the

freedom to fill Captain's vacancies during the period while the

Kirkland list was being developed, so long as the appointments

~n Intervenor Leath agrees with the State defendants' conclusion

that their decision not to use Bushey does not violate State law.

8

were made in a non-discriminatory manner. JA. 702. • The

Settlement Agreement did not compel defendants to make interim

appointments and they limited their freedom in this regard when

9

they agreed to the November 4, 1983 Stipulation.

8

Since the Bushey list had a severe adverse impact on minority

candidates, even interim use of its unadjusted results would have

violated the Settlement Agreement's non-discrimination mandate.

Agreement Art. IV, M 2, JA. 702. Also, Title VII requires that

interim appointments be made in a manner that avoids an adverse

racial impact. E .g., Guardians Ass'n of New York City v. Civil

Service Comm'n., 630 F.2d 79, 108-09 (2d Cir. 1 980 ) , cert. denied,

452 U.S. 940 (1981).

Two of the Wells intervenors filed affidavits stating that they

understood "that the Bushey Captain Eligible List would be used

to make permanent Captain appointments during the full period

prior to the time specified in the Kirkland stipulation for the

establishment of a new Captain eligible Tist." JA. 902, 904.

However, it is clear that the Kirkland Settlement Agreement did

not compel the Kirkland defendants to make interim appointments

from the Bushey list or otherwise. The Settlement Agreement set

a deadline by which the new list had to be published, but the

defendants were free to issue the new list at any time prior to

the deadline. In fact, under the Settlement Agreement, the

defendants could have issued the new list immediately, without

ever publishing the results of the 1982 examination.

Moreover, as noted above, the Kirkland Agreement gave the

defendants flexibility to make non-discriminatory use of the

results of the 1982 examination as an interim selection device

pending development of the new K i rkland list. Thus, it is

possible that these Wells intervenors believed that the State

defendants would take advantage of that option. The fact that

the Wells intervenors may have held a particular belief about the

way the defendants might act in the future does not mean the

Agreement compelled the defendants to act in accordance with that

belief.

9

The purpose of the Kirkland settlement was to produce a new,

job-related selection procedure as soon as possible, while

leaving defendants free to meet their operational needs by

filling current vacancies on an ongoing basis. The fact that

non-d iscr iminatory interim appointments were permitted does not

mean that such appointments could be made once the results of a

new, job-related selection procedure became available. Use of a

non-job-related interim measures became illegal once a job

related selection procedure became available. See e,g., Guar

dians A s s ’n , 630 F . 2d at 1 08-09 . Moreoever, the specific

deadlines set forth in the Settlement Agreement demonstrate that

the parties intended the Kirkland list to be used as soon as pos-

1 0

sible.

Plaintiffs and the Wells intervenors rely on their assertion

that Judge Griesa stated in an off-the-record conference that the

Kirkland Settlement Agreement did not address the effect of the

̂ The defendants were required to "use their best efforts" to

develop the new selection procedure earlier than the mandatory

deadline. Agreement Art. VI, 1| 6, JA. 708. Moreover, in

contrast with the provisions governing the new Lieutenant's

examination, the defendants were permitted to administer and use

the new procedure as soon as possible. Compare Art. VI, 1[ 5, JA.

707-08, with Art. VI, 11 6, JA. 708. These provisions further

demonstrate the Kirkland parties' intent to use the Kirkland

list as soon as possible and to use interim selection measures

for as few appointments as possible.

The contention that the Bushey list should be used to fill over

40 of the 60 total captain's positions in the system, see P1. Br.

at 6, completely violates this intent and would mean that

two-thirds of all the captains in the system were appointed under

non-job-related, interim procedures.

10

Kirkland list on the Bushey list. P1. B r . at 12; Wells Br. at

12, 30. Intervener Leath emphatically disputes this assertion.

ADD. 26, 41. The conference at issue lasted approximately ten to

fifteen minutes. Judge Griesa asked whether there was any

allegation of non-compliance with the Kirkland settlement. The

parties to the Kirkland settlement indicated that there was not.

Judge Griesa then indicated that he saw no reason to get in

volved. JA. 636-37. At no point in the conference did Judge

Griesa attempt to interpret the Kirkland Settlement Agreement.

Moreoever, an offhand comment made in an off-the-record

conference does not constitute a ruling or judgment and cannot be

1 2

given any binding effect. The only official action taken by

Judge Griesa was to reject the Bushey plaintiffs' motion to

intervene in the Kirkland case and to enjoin use of the Kirkland

list. If the Bushey plaintiffs or the Wells intervenors believed

that Judge Griesa's action in rejecting this motion was erron

eous, the appropriate course would have been to file an appeal or

11 Defendants had indicated their intent to comply with the Kirkland

settlement by using the Kirkland list, so there wasno issue of

non-compliance.

'1 To give any binding effect to an informal, off-the-record comment

would violate the due process rights of the parties. Although

the Bushey plaintiffs submitted written motion papers to Judge

Griesa, intervener Leath and the Kirkland class and the defen

dants did not see the papers until a few minutes prior to the

conference and were not given any opportunity to respond.

11

a writ o£ mandemus. The fact that Judge Gr

tiffs' direct attack on the Kirkland consent

a collateral attack on the settlement proper.

iesa rejected plain-

order does not make

1 3

Respectfully submitted,

6 W a&. o.

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

PENDA D. HAIR

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR

DEFENDANT-INTERVENOR-APPELLANT

GLENDA F. LEATH

3 The Wells intervenors argue that the cases cited by Intervenor

Leath concerning the illegality of the collateral attack on the

Kirkland consent order are inapplicable because some of the

collateral attackers (the Wells intervenors) were parties to the

Kirkland Settlement. Wells Br. at 29, n.22. This is a meaning

less distinction. Parties to a consent order have agreed to its

terms and to the jurisdiction of the court that entered the

decree. They are thus more restricted in their ability to launch

a collateral attack than non-parties. The cases cited by

intervenor Leath, which hold that even non-parties, who had no

opportunity to contest the decree, are precluded from collateral

ly attacking it, apply with even more force to parties to the

decree .

1 2

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I served the attached Reply Brief

of Defendant-Intervenor-Appellant Glenda F. Leath, by

depositing copies thereof, in the United States mail, first

class postage prepaid, properly addressed to:

Charles R. Fraser, Esq.

New York State Department of Law

49th Floor

2 World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

Steven Houck, Esq.

Donovan, Leisure, Newton & Irvine

30 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, New York 10112

Ronald G. Dunn, Esq.

Rowley, Forrest & O'Donnell, P.C.

90 State Street

Albany, New York 12207

$ \ m c L<x £).

Attorney for Defendant-

In tervenor-appe11ant

Glenda F. Leath