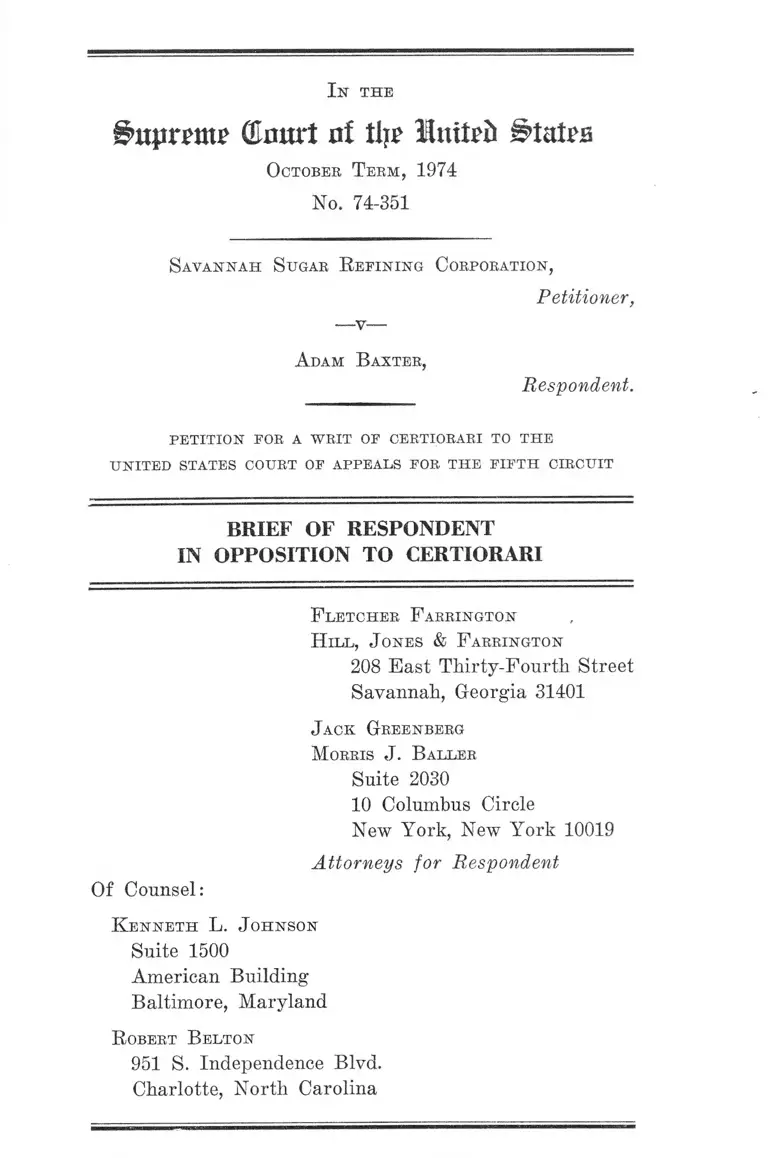

Savannah Sugar Refining Corp v Baxter Brief of Respondent in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1974

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp v Baxter Brief of Respondent in Opposition to Certiorari, 1974. ee6894bc-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76423d7a-3724-4d56-80ec-bd89591c10d7/savannah-sugar-refining-corp-v-baxter-brief-of-respondent-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

fsatpmtte (Unurt of Hip United States

O ctober T erm , 1974

No. 74-351

S avan n ah S ugar R efin in g C orporation,

Petitioner,

——v—

A dam B axter,

Respondent.

P E T IT IO N FOR a W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E

U N IT E D STATES COURT OF A PPEALS FOR T H E F IF T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

F letcher F arrington

H ill , J ones & F arrington

208 East Thirty-Fourth Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

J ack G reenberg

M orris J . B aller

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondent

Of Counsel:

K en n eth L. J ohnson

Suite 1500

American Building

Baltimore, Maryland

R obert B elton

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ....................... 1

Jurisdiction ........ 1

Questions Presented .................................... 2

Statement ............. 2

Argument—

I. The Ruling of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit is Entirely Consistent With

This Court’s Decision in McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green ............................................ 4

II. Petitioner’s Racially Discriminatory Promo

tional Policies Were Not Mandated by State

Law ............................................ 7

III. Good Faith Efforts Which Produce No Re

sults Are No Defense to a Back Pay Award

Under Title VII .. ......................... 7

Conclusion ................................................................ 10

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Ash v. Hobard Mfg. Co., 483 F.2d 289 (C.A. 6) ........... 8

Boles v. Union Camp Corp., 57 F.R.D. 46, 52 (S.D. Ga.) 7

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 406 F.2d 399

(C.A. 5) ...................................................... 4

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 ........ .............. 4, 9

Harvey v. International Harvester Co., 56 F.R.D. 47,

48 (N.D. Cal.) 7

II

PAGE

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(C.A. 5) ............................................................................ 4

Kober v. Westinghouse Electric Corporation, 480 F.2d

240 (C.A. 3) .................................................................... 7,8

LeBlanc v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 460 F.2d 1228

(C.A. 5), cert, denied 409 U.S. 990 ...... ...................... 8

Local 53, International Association of Heat & Frost

Insulation & Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (C.A. 5) .................................................................. 7

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 .......... ........................ 4

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 ................... 7

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 ....3, 4, 5, 6

Manning v. General Motors Corporation, 466 F.2d 812

(C.A. 6) ..... 7,8

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, 433

F.2d 421 (C.A. 8) ............................................... .'......... 3,9

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (C.A.

9) ....................................................................................... 7,8

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company, 451

F.2d 418 (C.A. 5), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 .......3, 4, 5, 6

Wernet v. Pioneer Foods Co., 484 F.2d 403 (C.A. 6) .... 8

Constitution:

United States Constitution, Amendment VII ............... 4

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ........ 1

Title VII of the Civil Bights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e, et seq.................................................................... 2, 4

In the

Supreme QJmtrt at % llniti'i States

O ctober T erm , 1974

No. 74-351

S avann ah S ugar. R efin ing C orporation,

Petitioner,

—v—

A dam B axter,

Respondent.

P E TIT IO N FOR A W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E

U N IT E D STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E F IF T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT

IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The opinion of the district court (Pet. App. pp. la-19a)x

is reported at 350 F.Supp. 139. The opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (Pet. App.

pp. 21a-41a) is reported at 495 F.2d 436. The order of the

court of appeals denying rehearing is reprinted at Peti

tioner’s Appendix p. 42a.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is founded upon 28 U.S.C.

§1254(1).

1 This form of citation refers to the Appendix to the Petition for

Certiorari filed in this Court on September 27, 1974.

2

Questions Presented

1. Did the court of appeals erroneously allocate the

burden of proof with respect to the relief required in a

Title YII case following an uncontested finding of discrim

ination based upon race?

2. Were Petitioner’s discriminatory promotional prac

tices mandated by state law?

3. Did the court of appeals err in holding that, despite

Petitioner’s efforts to end discrimination, it continued

unlawfully to deny promotions to its black employees?

Statement of the Case

Until it begins describing the ruling of the district court

(Petition, p. 4), the Statement of Petitioner accurately sets

forth the history of this litigation. At that point, however,

the Statement strays from the record. It conspicuously

omits mention of the district court’s ruling that Petitioner’s

promotional practices violated Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq. (Pet. App. lla-12a),

a ruling not contested by Savannah Sugar on appeal.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s finding

that Petitioner’s promotional policies, in general, violated

Title VII, and expressly approved the trial court’s adop

tion of affirmative remedies to cure that discrimination

(Pet. App. 30a). It also agreed that Respondent Baxter

had not himself been the victim of discrimination in the

Company’s failure to promote him to the position of Relief

Boiler Room Operator. The appeals court did not agree,

however, with the trial court’s ruling that monetary relief

was not required. It held that the trial court had imposed

3

an improper burden of proof in requiring Respondent to

show, in a trial where the issue was whether the Company

had discriminated in the first instance, that individual

members of the class were entitled to such relief (Pet. App.

33a). The Court of Appeals also ruled that good faith

efforts by the Company provided no defense to a back pay

award where discrimination continued despite those good

faith efforts (Pet. App. 32a).

ARGUMENT

Petitioner is thoroughly confused as to the meaning of

this Court’s decision in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792, and the decision of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Jackson

ville Terminal Company, 451 F.2d 418 (C.A. 5), cert, denied

406 U.S. 906 (1972). Both those decisions deal with the

order of proof and the nature of proof (separate issues

which Petitioner does not recognize as such) required to

prove discrimination. Neither of those opinions are ad

dressed—as is the opinion in issue here—to the order or

nature of proof required to show the necessity for monetary

relief once discrimination against a class has been shown.

Accordingly, Petitioner’s arguments are irrelevant and ill-

conceived.

Petitioner suggests that the opinion below is in conflict

with those cases which have denied back pay where the em

ployer’s discriminatory conduct was mandated by state

law. That suggestion is obtuse. Petitioner’s further sug

gestion of similarity between the facts of this case and those

of Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, 433

F.2d 421 (C.A. 8), is equally vacuous. There is no reason

to grant the writ in this case.

4

I

The Ruling of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit Is Entirely Consistent With This Court’s Deci

sion in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green.

The relatively short history of Title VII litigation has

spawned three generations of issues. The first generation

was born of the procedural aspects of the statute: whether

EEOC is required to attempt conciliation before an ag

grieved party may bring suit,2 whether the EEOC may refer

to a state agency a charge filed initially with it,3 whether

jury trials are required under the Seventh Amendment,4

and a host of other such questions. The second-generation

issues resolve around what happens to complaining parties

after they come to court: what constitutes discrimination,5

and what manner of proof complainants are required to

adduce in order to substantiate their claims.6 In the third

generation of Title VII cases, courts are facing the problem

of what to do after a complaining party comes to court

and wins, i.e., proves discrimination. The issues presented

by this case belong to that third generation.

The egregious flaw in Savannah Sugar’s Petition is that

it confuses the second-generation issues addressed by this

Court in McDonnell Douglas Corporation v. Green, 411

U.S. 792, and by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Company, supra, with the third-generation questions of

relief which form the basis of the opinion below.

2 Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco By. Co., 406 F.2d 399 (C.A. 5).

3 Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522.

4 Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122 (C.A. 5).

5 Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424.

6 McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792.

5

In McDonnell Douglas Corporation v. Green, supra—a

second generation case involving only an individual claim

of discrimination7—this Court held that, with respect to

the order of proof, the complainant in a Title VII suit

has the initial burden of proving discrimination (Step 1).

With respect to the nature of proof required in Step 1, this

Court set forth specifications by which the complainant

could have created—and did—a prima facie showing of

discrimination. This Court noted, however, that

The facts necessarily will vary in Title VII cases, and

the specification above of the prima facie proof re

quired from the complainant in this case is not neces

sarily applicable in every respect to differing factual

situations. [411 U.S. at 802, n. 13.]

The Court further held that, following plaintiff’s prima

facie showing, the proper order of proof requires that the

burden shift to the defendant to articulate legitimate, non-

discriminatory reasons for its employment decision (Step

2) .

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit in United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company,

supra, held, with respect to the order of proof, essentially

the same thing: the burden of proof was initially on plain

tiff to establish a prima facie case. With respect to the

nature of proof required in Step 1, the Fifth Circuit recog

nized the principle later established by this Court—that

the nature of proof of necessity will depend upon the facts

of each case— and held that plaintiff met its burden with

its introduction of statistical data. 451 F.2d at 444. With

7 The court expressly noted that, “ The critical issue before us

concerns the order and allocation of proof in a private, non-class-

action challenging employment discrimination,” 411 U.S. at 800.

The Court did not address problems of proof arising in class ac

tions where class-wide discrimination practices have been shown.

6

regard to Step 2, the Fifth Circuit looked to Jacksonville

Terminal for a “ plausible racially neutral explanation,”

451 F.2d at 445— a legitimate, non-discriminatory reason—

for its apparently discriminatory policies. In both Mc

Donnell Douglas and Jacksonville Terminal, the employers

were able to meet their Step 2 burden.

The approach of the district court in this case is sub

stantially identical to the approach used in McDonnell

Douglas and Jacksonville Terminal. In essence, the district

court found that Respondent met his initial, Step 1 burden

of proving discrimination by the introduction of statistical

data (see Pet. App,, pp. 17a-19a). The court then held that

Petitioner failed to carry its Step 2 burden of meeting the

prima facie showing, because of its lack of objective, ascer

tainable standards for promotion. It is this Step 2 issue

which, as evidenced by its querulous Statement (Petition,

pp. 4-8), Petitioner now seeks to relitigate in this Court.

Since it took no appeal from the district court’s findings,

Petitioner can not now be heard to complain that the court

of appeals’ express approval (Pet. App. 30a) of the dis

trict court’s findings is erroneous.

It is not the second-generation issue of discrimination

which forms the substance of the opinion below, but the

third-generation issue of appropriate relief following a

finding of discrimination. And, it is upon that issue that

the court of appeals differed with the holding of the dis

trict court. With respect to the order of proof on appro

priate relief, the court of appeals held that it was improper

to require plaintiff to establish entitlement of individual

class members to monetary relief prior to the resolution

of the discrimination issue. That holding in no way con

flicts with McDonnell Douglas Corporation v. Green, supra,

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company, supra,

or any other Title VII case of which Respondent is aware.

7

In fact, that holding is in accord with the practice of lower

courts both within and without the Fifth Circuit.8 Not

only is the Court of Appeals ruling amply supported by

those other cases; it is eminently sensible.

If Petitioner’s argument can be read at all to attack

the Court of Appeals’ approach to the relief issue, it does

not, as the titles suggest, assail the court’s allocation of

the order of proof. Rather, Petitioner quarrels with the

nature of proof which will be required of individual class

members to establish their entitlement to back pay. That

issue was not before the Court of Appeals, and was wisely

and appropriately remanded by it to the district court for

that determination to be made. Cf. Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154ff; Local 53, International Asso

ciation of Heat & Frost Insulation and Asbestos Workers

v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (C.A. 5). The ruling of the Court

of Appeals therefore provides no basis whatsoever for

issuing the writ.

II

Petitioner’ s Racially Discriminatory Promotional

Policies Were Not Mandated by State Law.

Petitioner argues that, since an award of back pay is

within the trial court’s discretion, and since the Court of

Appeals failed to invoke the magic words, “abuse of dis

cretion” in reversing the trial court (Petition, p. 17), the

opinion below creates an “ immutable” conflict with Kober

v. Westinghouse Electric Corporation, 480 F.2d 240 (C.A.

3 ); Manning v. General Motors Corporation, 466 F.2d 812

(C.A. 6 ); and Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d

1002 (C.A. 9). Petitioner’s argument has no merit. Each

8 Boles v. Union Camp Corporation, 57 F.R.D. 46, 52 (S.D.G-a.) ;

Harvey v. International Harvester Co., 56 F.R.D. 47, 48 (N.D.Cal.).

8

of those cases involved sex discrimination claims where

the employment practices under attack were mandated

by state protective legislation. The denial of back pay in

these cases was based on the presumptive constitutional

ity of state legislative enactments and the fact that their

mandatory nature put the employers on the horns of a

dilemma from which only a federal court Title VII rul

ing could release them. Those cases, and a few others

like them,9 comprise the universe of appeals court deci

sions which have affirmed the exercise of discretion by

lower courts in denying back pay, where discrimination

and resultant economic loss was proved. Petitioner can

take no comfort in those cases. It had a completely free

hand to adopt and implement its promotional policies, and

was under no state-imposed obligation to allow its all-

white supervisory staff to be the sole arbiter of qualifi

cations (See Pet. App. pp. lOa-lla, 30a). The facts of

Kober, Manning and Schaeffer have nothing to do with

the facts of this case of voluntary private discrimination.

Accordingly there exists no conflict of authorities.

Ill

Good Faith Efforts Which Fail to Terminate Dis

crimination Are No Defense to a Back Pay Award

Under Title VII.

Petitioner argued below, and the district court so held,

that its good faith efforts to end its discriminatory prac

tices was reason enough to deny back pay to those members

of the class who had suffered economically as a result of

those practices (Pet, App., p. 13a). The Fifth Circuit re

9 Ash v. Hobart Mfg. Co., 483 F.2d 289 (C.A. 6 ) ; Wernet v.

Pioneer Foods Co., 484 F.2d 403 (C.A. 6) ; LeBlanc v. Southern

Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 460 F.2d 1228 (C.A. 5), cert, denied 409 U.S.

990.

9

versed, holding that neither an employer’s beneficence nor

his malevolence are proper criteria to apply in determin

ing appropriate relief (Pet. App., p. 32a).

Petitioner argues that the Court of Appeals’ reversal has

created a conflict with the Eighth Circuit’s ruling in

Parham, v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d

421 (C.A. 8). That argument ignores the plain mandate

of Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, where this

Court held that

. . . good intent or absence of discriminatory intent

does not redeem employment procedures . . . that

operate as ‘built-in headwinds’ for minority groups and

are unrelated to measuring job capability. . . . Con

gress directed the thrust of the Act to the consequences

of employment practices, not simply the motivation.

[401 U.S. at 432, emphasis the Court’s.]

Both the Parham court and the court below in this case

followed that mandate: they examined the consequences

—not the motivation— of the employment practices under

attack. In Parham, the court, found that Southwestern Beil

had embarked on a good faith journey toward equal em

ployment opportunity and had succeeded. In this case,

both the trial court and the Court of Appeals found that,

despite Petitioner’s good faith efforts, discrimination con

tinued unabated (Pet. App., pp. 9a-10a, 32a).

The Fifth Circuit in this case and the Eighth Circuit

in Parham used the same analytical approach to deter

mine the relief required. The results were different be

cause the facts were different: Southwestern Bell had

stopped discriminating; Savannah Sugar had not. Those

differing factual situations do not amount to conflicts of

rulings of law. There is therefore no reason to grant the

writ on that basis.

10

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Respondent respectfully sub

mits that the writ should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

F letcher F arrington

H ill , J ones & F arrington

208 East Thirty-Fourth Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

(912) 233-7727

J ack Greenberg

M orris J . B aller

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Respondent

Of Counsel:

K en n eth L. J ohnson

Suite 1500

American Building

Baltimore, Maryland

R obert B elton

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina

ME!IEN PRESS INC. — N. Y C 219