Restoration of "Good Time" for New York State Prisoners

Press Release

January 25, 1972

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Restoration of "Good Time" for New York State Prisoners, 1972. e81f3bbf-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76506362-e1fb-4edf-9ebb-e1c2ffd72611/restoration-of-good-time-for-new-york-state-prisoners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

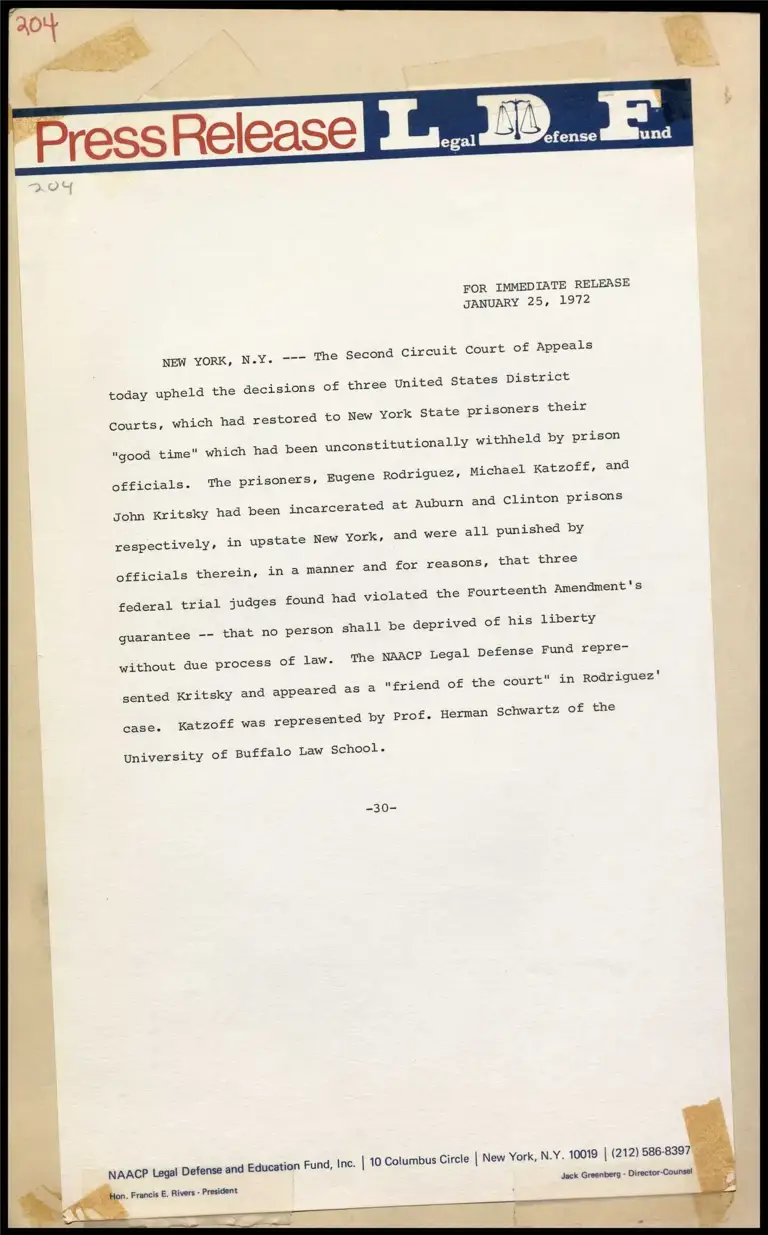

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

JANUARY 25, 1972

NEW YORK, N.Y. --7~ The Second Circuit court of Appeals

today upheld the decisions of three United States District

courts, which had restored to New york State prisoners their

"good time” which had been unconstitutionally

withheld by prison

officials. The prisoners, Eugene Rodriguez, Michael Katzoff, and

John Kritsky had been incarcerated at Auburn and Clinton prisons

respectively, in upstate New York, and were all punished by

officials therein, in a manner and for reasons, that three

federal trial judges found had violated the Fourteenth Amendment's

guarantee -— that no person shall be deprived of his liberty

without due process of law. The NAACP Legal Defense Fund repre-

sented Kritsky and appeared as a "friend of the court" in Rodriguez '

case. Katzoff was represented by prof. Herman Schwartz of the

University of Buffalo Law School.

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 40 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

on. Francis E. Rivers - President

Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel a.

ma