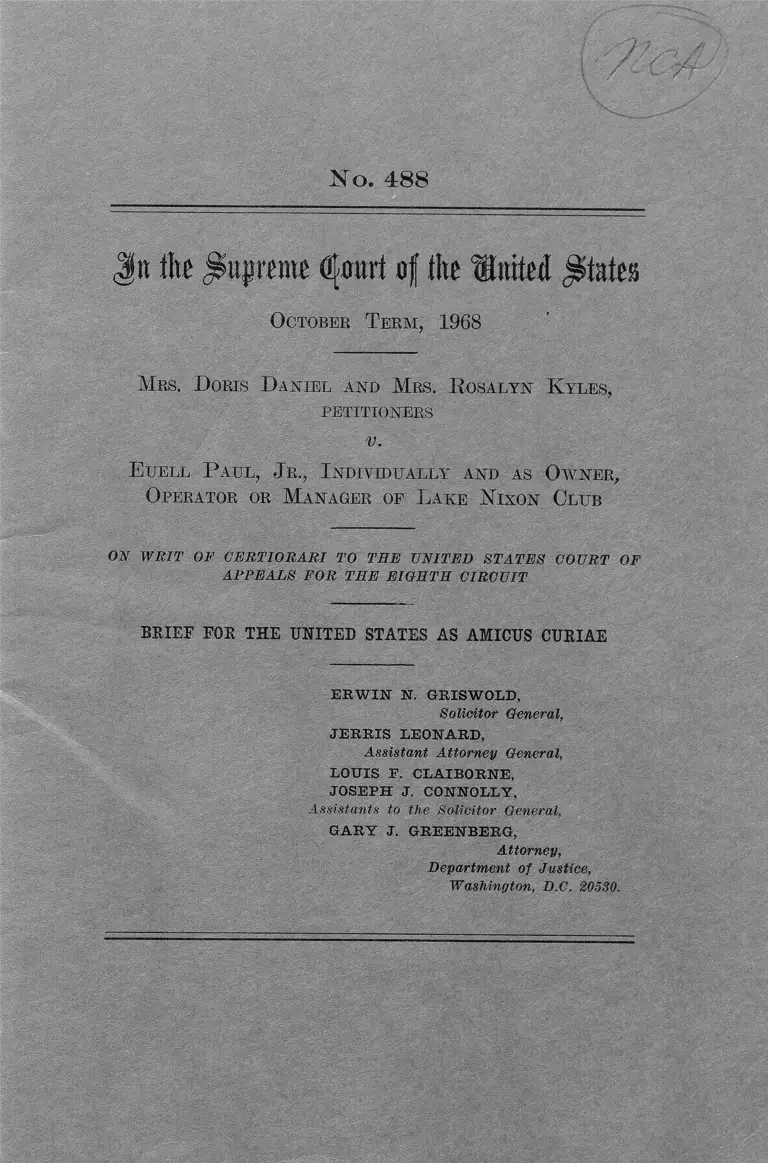

Daniel v. Paul Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daniel v. Paul Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1969. 682df2eb-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/767f8af5-663f-446d-98e3-23a4206d379f/daniel-v-paul-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

.N o. 4 8 8

\n the Supreme (§mxt tff the ‘Suited States

October Term, 1968

Mrs. D oris D aniel and Mrs. R osalyn K yles,

PETITIONERS

V.

E tjell P aul, J r., I ndividually and as Owner,

Operator or M anager op L ake N ixon Club

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

E R W IN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General,

JE R R IS LEONARD,

Assistant Attorney General,

LOUIS E. CLAIBORNE,

JOSEPH J. CONNOLLY,

Assistants to the Solicitor General,

G A R Y J. GREENBERG,

Attorney,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction___________________________________ 1

Questions presented____________________________ 2

Statutory provisions involved___________________ 2

Statement_____________________________________ 4

Argument:

Introduction and summary_________________ 6

I. Racial discrimination in the sale of admis

sions to the Lake Nixon Club violates

Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866

(now 42 U.S.C. 1981, 1982)___________ 9

A. Section 1981, on its face, bars re

spondent’s conduct_____________ 9

R. Section 1982, on its face, also bars

respondent’s conduct___________ 13

C. Subsequent enactment of a public

accommodations law in 1875 does

not indicate that the rights claimed

here were beyond the scope of the

1866 legislation_________________ 14

D. This Court’s decision in the Civil

Rights Cases is not a viable obstacle

to our conclusion_______________ 19

E. The public accommodations law of

1964 does not affect the coverage

of the 1866 act_________________ 22

as

-333- 097— 69 1

II

Argument—Continued Page

II. The exclusion of petitioners, by reason of

their race, from the enjoyment of the

facilities of Lake Nixon Club violates

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964__ 27

A. Section 201(b)(4) brings Lake Nixon

within the coverage of the 1964

act____________________________ 28

B. Section 201(b)(3) brings Lake Nixon

within the coverage of the 1964

act____________________________ 34

Conclusion__________________ __________________ 40

Cases:

Amos v. Prom, Inc.. 117 F. Supp. 615_______ 37

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226_____________ 15, 21

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632,140 S.E. 2d 866_ _ 31

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3______ 15, 19, 20, 21, 22

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S.

363_____________________________________ 12

Coger v. North West. Union Packet Co., 37

Iowa 145________________________________ 16

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 13Q__ 14

Donnell v. State, 48 Miss. 661_______________ 16

Drews v. Maryland, 381 U.S. 421___________ 30

Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64_______ 12

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474__ 29

Fazzio Real Estate Co. v. Adams, 396 F. 2d 146,

affirming 268 F. Supp. 630_______________ 29

Ferguson v. Gies, 82 Mich. 358_____________ 16

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368______________ 34

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F. 2d 509------------------- 31, 33

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306____ 14,

30, 31, 33, 37

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379

U.S. 241__________________________ 9,21, 33, 37

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1_________ 20

Ill

Cases— Continued PaSe

Howard v. Lyons, 360 U.S. 593___________ 12

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409___________ 7,

9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23. 24,

25, 37

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294_______ 40

Marrone v. Washington Jockey Club, 227 U.S.

633_____________________________________ 11

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394 F.

2d 342, reversing 391 F. 2d 86___________ 9,

35, 36, 39, 40

Nesmith v. YMCA of Raleigh, 397 F. 2d 96__ 9, 30

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 377

F. 2d 433, affirmed as modified, 390 U.S.

400____________________________________ 30

Scott v. Young, 12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 428__ 29

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 392 U.S.

657_____________________________________ 14

Textile Workers v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S.

448_____________________________________ 12

United States v. All Star Triangle Bowl, Inc.,

283 F. Supp. 300_________________________ 29, 34

United States v. Beach Associates, Inc., 286 F.

Supp. 801_______________________________ 30, 34

United States v. Fraley, 282 F. Supp. 948____ 29

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745_________ 20

United States v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 563________ 27, 36

United States v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383________ 17, 36

United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787_________ 17, 36

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch

103_____________________________________ 14

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 332 U.S.

301_____________________________________ 12

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70_____ 17

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697, reversing 75

F. Supp. 543 12

XV

Cases—Continued Page

Virginia, Ex Parte, 100 U.S. 339____________ 15

Watkins v. Oaklawn Jockey Club, 86 F. Supp.

1006, affirmed, 183 F. 2d 440_____________ 11

Williams v. Kansas City, Missouri, 104 F,

Supp. 848, affirmed, 205 F. 2d 47, certiorari

denied, 346 U.S. 826_______________________ 11

Willis v. Pickrick Restaurant, 231 F. Supp.

196, appeal dismissed, 382 U.S. 18__________ 31

Woolen v. Moore, 400 F. 2d 239____________ 31, 33

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Constitution:

Thirteenth Amendment_________ 14, 20, 21, 25

Fourteenth Amendment_________15, 16, 17, 25

Civil Eights Act of 1866, Act of April 9,

1866, 14 Stat. 27:

Section 1________________________ 9, 10, 14, 15

Section 2_____________________________ 18

Enforcement Act of 1870, Act of May 31, 1870,

16 Stat. 140:

Section 16__________________________ 10

Section 18__________________________ 10

Civil Rights Act of 1875, Act of March 1,1875,

18 Stat. 335:

Section 1_____________________________ 15

Section 2__________________________ 15, 18,19

Section 3_____________________________ 15, 19

Section 4_____________________________ 15

Section 5_____________________________ 15

V

Constitution and statutes—Continued page

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II, 42 U.S.C.

2000a to 2000a-6:

Section 201(a), 42 U.S.C. 2000a(a)„__ 3, 23, 27

Section 201(b), 42 U.S.C. 2000a(b)-------- 2,

3, 6, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37,

38, 39

Section 201(c), 42 U.S.C. 2000a(c)-------- 3,

24, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40

Section 201(e), 42 U.S.C. 2QQQa(e)_____ 6, 28

Section 203(a), 42 U.S.C. 2000a-2(a)_.-_ 27

Section 204(a), 42 U.S.C. 2000a-3(a)„_. 24, 27

Section 204(d), 42 U.S.C. 2000a-3(d)____ 24

Section 206, 42 U.S.C. 2000a-5------------- 24

Section 207(b), 42 U.S.C. 2000a-6(b).___ 25, 27

Title X, 42 U.S.C. 2000g et seq.;

Section 1001, 42 U.S.C. 20Q0g------------- 24

Section 1002, 42 U.S.C. 2Q00g-l------------ 24

Section 1003, 42 U.S.C. 2GQQg-"2------------ 24

Section 1004, 42 U.S.C. 20Q0g-3------------ 24

Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII, 82 Stat.

81, 42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq_________________ 23, 24

42 U.S.C, 1981 (R.S. 1977)________________ 2,

6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

42 U.S.C. 1982 (R.S. 1978)____________ 2,

9, 10, 13,14, 23, 24, 25

18 U.S.C. 241_____________________________ 17

18 U.S.C. 242_____________________________ 17,18

18 U.S.C. 243_____________________________ 15

Miscellaneous:

Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess----- 7, 16

Congressional Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess.------ 16

2 Cong. Rec.:

p. 340________________________________ 17

p. 4082_______________________________ 18

VI

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

109 Cong. Rec. 3248_______________________ 7

110 Cong. Rec.:

p. 4856_______________________________ 31

p. 6533_______________________________ 8

pp. 7398, 7402________________________ 38

pp. 7406-7407_________________________ 29

pp. 13915, 13912______________________ 40

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amend

ment (1908)_____________________________ 16

Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding

of “ Equal Protection of the Laws,” 50 Coluni.

L. Rev. 131_____________________________ 15

Gressman, The Unhappy History of Civil Rights

Legislation, 50 Mich. L. Rev. 1323_________ 16

Hearings on Civil Rights before Subcommittee

No. 5 of the House Committee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess___________ 8, 30

Hearings on H.R. 7152 before the House Com

mittee on Rules, 88th Cong., 2d Sess______ 8, 29

Hearings on S. 1732 before the Senate Com

mittee on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess__ 25, 30

H. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess_______29, 37

S. Rep. 872, 88th Cong., 2d Sess____________ 40

Webster’s New Third International Diction

ary 37

Jit M ilitjtttme fymi of th ISitM JSMeii

October Term, 1968

No. 488

Mrs. D oris D aniel and Mrs. R osalyn K yles,

PETITIONERS

V.

E uell P all, J r., I ndividually and as Owner,

Operator or M anager op L ake N ixon Club

•ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court (A. 47-62) is

reported at 263 P. Supp. 412. The majority and dis

senting opinions of the court of appeals (A. 64-90)

are reported at 395 P. 2d 118.

j u r i s d i c t i o n

The judgment of the court of appeals (A. 91) was

entered on May 3, 1968. A petition for rehearing en

3banc (A. 92-102) was denied on June 10, 1968 (A.

103). The petition for a writ of certiorari was filed

on September 7, 1968, and granted on December 9,

1968 (A. 105). The jurisdiction of this Court rests

on 28 IT.S.C. 1254(1).

(i)

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether 42 U.S.C. 1981 and 1982 guarantee to*

Negroes the right to purchase admission to a pri

vately owned place of amusement, such as the Lake

Nixon Club, which is open to white members of the

general public.

2. Whether the Lake Nixon Club is subject to the

proscriptions of Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 under Section 201(b)(4) of the Act (42 U.S.C.

2000a(b)(4)) by reason of the operation on its

premises of an eating facility which is itself cov

ered under Section 201(b)(2) of the Act (42 U.S.C.

2000a(b)(2)).

3. Whether the Lake Nixon Club is a “ place

of * * * entertainment” within the meaning of Sec

tion 201(b)(3) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. 2000a(b)(3)) and is thereby subject to the*

proscription of Title I I of the Act.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Sections 1981 and 1982 of Title 42 of the United

States Code provide in pertinent part:

§ 1981. All persons within the jurisdiction o f

the United States shall have the same right in

every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts * * * as is enjoyed by white citi

zens * * *.

§ 1982. All citizens of the United States shall

have the same right, in every State and Terri

tory, as is enjoyed by white citizens thereof to

inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property.

3

The relevant provisions of Title I I of the Civil

Rights Act o f 1964 (42 U.S.C. 2000 el seq.) are as

follows:

§ 201(a) (42 U.S.C. 2000a(a)). All persons

shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoy

ment of the goods, services, facilities, privi

leges, advantages, and accommodations of any

place of public accommodation, as defined in

this section, without discrimination or segre

gation on the ground of race, color, religion, or

national origin.

§ 201(b) (42 U.S.C. 2000a (b )) . Each of the

following establishments which serves the public

is a place of public accommodation within the

meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce * * *:

* * * * *

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunch

room, lunch counter, soda fountain, or

other facility principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the prem

ises * * *;

(3) any motion picture house, theater,

concert hall, sports arena, stadium or

other place of exhibition or entertain

ment; and

(4) any establishment (A ) * * * (ii)

within the premises of which is physi

cally located any such covered establish

ment, and (B ) which holds itself out as

serving patrons of such covered estab

lishment.

§ 201(c) (42 U.S.C. 2000a(c)). The opera

tions of an establishment affect commerce with

3 3 3 -0 9 7 — 69-------2

4

in the meaning of this title if * * * (2) in the

ease of an establishment described in paragraph

(2) of subsection (b), it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers or a substantial portion of

the food which it serves * * * has moved in

commerce; (3) in the case of an establishment

described in paragraph (3) of subsection (b ),

it customarily presents films, performances,

athletic teams, exhibitions, or other sources of

entertainment which move in commerce; and

(4) in the case of an establishment described

in paragraph (4) of subsection (b) * * *

there is physically located within its premises,,

an establishment the operations of which affect

commerce within the meaning of this subsec

tion. For purposes of this section, “ commerce”

means travel, trade, traffic, commerce, trans

portation, or communication among the several

States * * *.

STATEM ENT

Lake Nixon Club is a privately owned place of

amusement located about 12 miles west of Little

Rock, Arkansas. Approximately 100,000 persons

patronize Lake Nixon each year (A. 43). The entire

establishment contains about 230 acres and includes

facilities for swimming, boating, pieknicking, sun

bathing, miniature golf, and dancing (A. 28-30, 41).

For the convenience of its patrons, Lake Nixon also

maintains a snack bar on the premises which sells

hamburgers, hot dogs, soft drinks, and milk pur

chased from local suppliers (A. 12-13, 30-32; see

note 12, infra). Gross income from the sale o f

food was approximately $10,500 during the 1966 sea

5

son, or about 23 percent of the total revenue for the

entire establishment (A. 13, 63).

The district court took judicial notice of the fact

that at least some of the ingredients of the bread

products and soft drinks sold at Lake Nixon had

moved in interstate commerce (A. 57). Fifteen paddle

boats which were used on the Lake were rented on a

royalty basis from an Oklahoma company (A. 28-

29), and two juke boxes maintained on the premises

were manufactured outside Arkansas (A, 62). Lake

Nixon was advertised over a local radio station and

in a monthly publication, designed to reach tourists

and visitors, which listed available attractions in the

Little Rock area (A. 55-56, see p. 32, infra).

The district court found that although it is unlikely

that an interstate traveler would break his trip to

visit Lake Nixon, “ it is probably true that some out-

of-state people spending time in or around Little

Rock” have patronized Lake Nixon (A. 56-57).

Lake Nixon has been operated as a racially segre

gated facility at least since respondent Euell Paul,

Jr., and his wife purchased it in 1962 (A. 15, 41).

Following the enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

the Pauls began to refer to their establishment as a

“ private club” (A. 54). Patrons have thereafter been

required to pay a 25-cent “ membership” fee, which

entitles them to enter the premises for an entire sea

son, and, on payment of certain additional fees, to

use the swimming, boating, and miniature golf facili

ties (A. 27-28). Although white persons are routinely

admitted to membership in the Lake Nixon Club,

6

Negroes are uniformly denied membership or admis

sion, because respondent feared that “ business would

be ruined” (A. 16, 44).

Petitioners, Mrs. Doris Daniel and Mrs. Rosalyn

Kyles attempted to use the facilities of Lake Nixon on

July 10, 1966, but were denied admission because they

are Negroes (A. 37, 44). Petitioners thereafter insti

tuted this class action against respondent, alleging

that his policy of refusing Negroes admission to Lake

Nixon was in violation of Title I I of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and of 42 U.S.C. 1981. In their complaint

petitioners prayed for an injunction requiring re

spondent to abandon the recially discriminatory ad

mission policy at Lake Nixon (A. 5).

Although finding that Lake Nixon was not a “ pri

vate club” within the exemption for such facilities

under Section 201(e) o f the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

the district court denied relief, holding that the Lake

Nixon Club was not a covered establishment under

either Section 201(b)(3) or 201(b)(4) of the Act

(A. 57-62). A divided court of appeals affirmed on

the ground that the evidence in the record failed to

establish any connection between Lake Nixon and

interstate commerce as required by the 1964 Act

(A. 78). Neither the district court nor the court of

appeals dealt with petitioners’ claim under 42 U.S.C.

1981.

ARGUM ENT

Summary and I ntroduction

The central issue in this case is whether an amuse

ment facility open to the general public may, con

sonant with the provisions of the Civil Rights Acts

7

of 1866 and 1964, exclude Negroes solely on the basis

of their race. Our submission is that it may not, be

cause the two statutes, sometimes overlapping, but

complementary, combine to outlaw all such discrimi

nation.

1. In 1866, Senator Trumbull of Illinois, Chairman

of the Senate Judiciary Committee, dealing with one

of the problems which confronted the “ Reconstruc

tion'’ Congress, spoke of the need to guarantee to the

former Negro slaves, whose freedom had just been

secured by the Thirteenth Amendment, the right “ to

make contracts and enforce contracts.” Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess., 43. He described the bill he

introduced on January 5, 1866—which later became

the Civil Rights Act of 1866—as a measure designed

affirmatively to secure for all men what he termed

the “ great fundamental rights,” including the right

“ to make contracts” {id. at 475). With reference to

the rights enumerated in the proposed legislation, the

Senator said the bill would “ break down all discrim

ination between black men and white men” {id. at

599). Speaking for this Court in 1968, Mr. Justice

Stewart said that, indeed, the 1866 Act “was meant to

prohibit all racially motivated deprivations of the

rights enumerated in the statute * * *.” Jones v.

Mayer Go., 392 U.S. 409, 426. We submit that the right

to purchase entry to, and to enjoy the benefits of, a

place of public amusement is among the rights pro

tected by the statute. {Infra, pp. 9-27.)

2. Addressing the Congress 97 years after Senator

Trumbull, President Kennedy, in his message of Feb

ruary 28, 1963, said (109 Cong. Rec. 3248, emphasis,

added):

8

No action is more contrary to the spirit of

our democracy and Constitution—or more right

fully resented by a Negro citizen who seeks

only equal treatment—than the barring of

that citizen from * * * recreational areas, and

other public accommodations and facilities.

To correct this injustice the President called for leg

islation “ to secure the right of all citizens to the full

enjoyment of all facilities which are open to the gen

eral public.” (Hearings on Civil Rights before Sub

committee No. 5 of the House Committee on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., Part II, p. 14-18

(Message of June 19, 1963)).

During the deliberations on the Administration’s

proposals, Representative Celler told the House Rules

Committee that Title I I “ seeks to remove the daily

affront and humiliation occasioned by discriminatory

denials of access to facilities open to the general

public.” Hearings on II.R. 7152 before the House

Committee on Rules, 88th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 91.

In the Senate, Senator Humphrey told his colleagues

(110 Cong. Ree. 6533) :

The grievances which most often have led to

protest and demonstrations by Negro Ameri

cans are the segregation and discrimination

they encounter in the commonly used and nec

essary places of public accommodation * * *.

No amount of oratory and quibbling can ob

scure the personal hardships and insults which

are produced by discriminatory practices in

these places. * * *

* * * We must make certain that every door

in our public places of amusement and culture

is open to men of black skin as well as white.

9

In surn, we must put an end to the shabby

treatment of the Negro in public places which

demeans him and debases the value of his

American citizenship.

Title I I of the 1964 Act, as finally passed, though

not unlimited in its coverage, was a “ most compre

hensive” measure designed to achieve that end. See

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S.

241, 246; Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394

F. 2d 342, 349, 352-353 (C.A. 5) fen banc) ; Nesmith

v. YMCA of Raleigh, 397 F. 2d 96, 100 (C.A. 4).

We believe it, too, encompasses the facility in suit.

{Infra, pp. 27-40.)

I. RACIAL D ISCRIM IN ATIO N IN TH E SALE OF ADMISSIONS

TO T H E LAK E N IXO N CLUB VIOLATES SECTION 1 OF TH E

CIVIL RIGH TS ACT OF 1 8 6 6 (N O W 4 2 U .S.C. 1 9 8 1 ,

1 9 8 2 )

A. SECTION 1981, ON ITS FACE, EARS RESPONDENT’S CONDUCT

Petitioners alleged in their complaint that respond

ent’s refusal to admit them, by reason of their race,

into membership in the Lake Nixon Club and to use

its facilities deprived them of rights secured by 42

U.S.C. 1981, which provides, in pertinent part, that

“ All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts * * * as is

enjoyed by white citizens * * We agree.

Whatever doubts may once have surrounded this

provision were settled by this Court’s decision, last

Term, in Jones v. Mayer Go., 392 U.S. 409, construing

42 U.S.C. 1982. Since both Section 1981 and Section 1982

10

derive from a single clause of Section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27),1 it seems evident

the two provisions must be given comparable scope.

Thus, like the right to “purchase [and] lease * * *

real and personal property,” the right to “ make and

enforce contracts” without discrimination on the basis

of race is not limited to the legal capacity to engage

in commercial transactions free from hostile state

action. It, too, is an every-day right to equality of

opportunity in business dealings—the “ same right”

as is enjoyed by white citizens—which the 1866 Act

1 Section 1 o f the Act o f 1866 read as follow s:

“ That all persons bom in the United States and not subject

to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby

declared to be citizens o f the United States; and such citizens,

of every race and color, without regard to any previous

condition o f slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punish

ment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly con

victed, shall have the same right, in every State and Territory

in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold,

and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security o f person

and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be sub

ject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none other,

any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the con

trary notwithstanding.”

The “ property” clause became separated when the rest o f the

provision, slightly expanded and made applicable to resident

aliens as well, was re-enacted in Jiaec verba as Section 16 o f the

Enforcement Act o f May 31, 1870 (16 Stat. 140, 144). The

property guarantee remained available to citizens alone as part

o f the 1866 Act, the whole of which was re-enacted (by refer

ence only) by Section 18 o f the Enforcement Act o f 1870. This

division was formalized in the Revised Statutes o f 1874, the

“property clause” being codified as Section 1978, the rest as

Section 1977, and persists today in Sections 1982 and 1981 o f

Title 42 o f the United States Code.

11

secures against racial discrimination by private per

sons as well as public authorities (392 TT.S. at 421-

424). Here, also, Congress meant exactly what it

said—that it intended “ to prohibit all racially moti

vated deprivations of the rights enumerated in the

statute * * * ” (id. at 426, 436). And it would seem

equally to follow that “ the statute, thus construed, is

a valid exercise of the power of Congress to enforce

the Thirteenth Amendment” (id. at 413). See discus

sion infra, pp. 19-21.

On its face, therefore, Section 1981 prohibits all

private, racially motivated conduct which denies or

interferes with the Negroes’ right to enter into con

tracts to purchase that which is freely sold to white

citizens. That membership in the Lake Nixon Club is

a contractual relationship can hardly be denied. The

record indicates that upon payment of the admittedly

small membership fee, white persons (thereafter

“ members” ) obtained the right for the remainder of

the season to enter onto the premises at no additional

charge and, on payment of additional fees, to make

use of Lake Nixon’s amusement and entertainment

facilities (A. 27-28). Even if the “ membership” fee

entitled a patron to admission on only one occasion,

it is clear that under common law principles a ticket

to a place of entertainment 6r recreation is regarded

as a contract. Watkins v. Oaklawn Jockey Club, 86

E. Supp. 1006, 1016 (W.D. Ark.), affirmed, 183 P. 2d

440 (C.A. 8) ; Williams v. Kansas City, Missouri, 104

P. Supp. 848, 859 (W.D. Mo.), affirmed, 205 P. 2d

47, 51 (C.A. 8), certiorari denied, 346 U.S. 826. As

Mr. Justice Holmes said in Marrone v. Washington

333- 097— 69 -3

12

Jockey Club, 227 U.S. 633, 636, with reference to a

ticket of admission to a race track, “ the purchase of

the ticket made a contract” and gave rise to a right

‘ ‘ to sue upon the contract for the breach. ’ ’ 2

It is of course unnecessary to decide here whether

every transaction or relationship which could formally

be characterized as “ contractual” brings Section 1981

into play. Thus, it may well be that membership in a

bona fide private club—not involved here (see p. 6,

supra, and n. 10, infra) —and other purely social or

personal arrangements are beyond the intended reach

of the statute. Our present submission is only that

ordinary commercial contracts are covered, including

those relating to privately-owned places of public ac

commodation, which—except for the race barrier—

admit all persons indiscriminately.

Indeed, that was the holding of Valle v. Stengel,

176 F. 2d 697 (C.A. 3), in which the plaintiffs sought

damages and injunctive relief, alleging that certain

individuals and police officers had discriminatorily re

fused to admit them to the swimming pool o f an

2 We do not consider whether an admission ticket is viewed

as a contract under Arkansas law. In light o f Jones, the fed

eral courts will be called upon to develop a body o f law as to

what, for example, constitutes “ property” under Section 1982

and “contracts” under Section 1981. That determination should

not be made subject to the laws o f the 50 State jurisdictions. Erie

R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, notwithstanding, it is clear that

in order that there be uniformity in the disposition o f such

matters as are within the area o f federal legislative jurisdic

tion, the federal courts are authorized to develop federal law.

E.g., Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363; Tex

tile Workers v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S. 448, 457; Howard v.

Lyons, 360 U.S. 593, 597. See also United States v. Standard

Oil Co., 332 U.S. 301, 307.

13

amusement park in violation of rights secured to them

by 42 U.S.C. 1981, 1982,3 and the Fourteenth Amend

ment.4 In reversing the district court’s dismissal of

the complaint (75 F. Supp. 543 (D. N .J .)), the court

o f appeals said (176 F. 2d at 702 (emphasis sup

plied.) ) :

[Plaintiffs] were ejected from the park, were

assaulted and were imprisoned falsely, as al

leged in the complaint, because they were Ne

groes or were in association with Negroes, and

were denied the right to make or enforce con

tracts, all within the purview of and prohibited

by the provisions of R. S. Section 1977 [42

U.S.C. 1981].

Here white members of the general public were al

lowed to make contracts giving them the right to enter

and use Lake Nixon’s facilities, while petitioners,

Negroes, were denied that right. We believe that con

duct constitutes a violation of Section 1981.

B. SECTION 1982, OX ITS FACE, ALSO BARS RESPONDENT'S CONDUCT

Although, in our view, the case is clearly embraced

by Section 1981, we believe respondent’s conduct also

violates 42 U.S.C. 1982—the provision construed in

Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, which guarantees all citi

zens, regardless of race, “ the same right * * *

to * * * purchase, lease * * * [and] hold * * * real

3 Then 8 U.S.C. 41 and 42; Sections 1977 and 1978 o f the

Revised Statutes.

4 Both the amusement park and the swimming pool lo

cated therein were private facilities open to the public upon

the payment, o f an admission fee. Plaintiffs, Negroes and their

companions, alleged that, although they were admitted to*? he

park, they were denied entry to the swimming pool because o f

the application o f a “ white only” admission policy.

14

and personal property. ’ ’ 5 Indeed, nominal as it may

be, the membership fee in Lake Nixon Club entitles

the patron to enjoy the real and personal property o f

the facility. Whether the benefit is viewed as a kind of

temporary lease or right of use appertaining to those

properties, or as a species of incorporeal personalty,

the transaction involves a “ purchase.”

We do not press the point. Our submission is

simply that the case is covered by Section 1981 or

Section 1982, if not both. Whatever may be the most

appropriate characterization of the right to enjoy

the benefits of the Lake Mxon facility, we have no

doubt that a Negro who is excluded by reason of his

race has suffered a loss of the freedom from racial dis

crimination secured by Section 1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866. As the Court said in Jones (392 U.S. at

443), the Congress which acted to secure the Negroes’

freedom under the Thirteenth Amendment to “ go and

come at pleasure” and to “buy and sell when they

please” did exactly what it intended to do—“ to assure

that a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase

the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a white

man.”

C. SUBSEQUENT ENACTMENT OE A PUBLIC ACCOMMODATIONS LAW IN

187 5 DOES NOT INDICATE THAT THE RIGHTS CLAIMED HERE WERE

BEYOND THE SCOPE OP THE 186(3 LEGISLATION

What has been said sufficiently shows that the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, on its faee, reaches the discrim

5 Although petitioners did not plead 42 U.S.C. 1982 as a

ground for, relief, the Court may consider issues arising under

that provision, Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts, 388 U.S.

130, 142-143; Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 392 U.S. 657,

and decide the case on that basis. See United States v. Schooner

Peggy, 1 Cranch 103, 110; cf. Hamm v. City of Roch Hill, 379

U.S. 306.

15

inatory policy of the 'Lake Nixon Club—whether

under the “ contract” clause of Section 1981 or the

“ property” clause of Section 1982. However, because

we are dealing with a “ place of public accommoda

tion,” which was the special subject-matter o f the

Civil Rights Act of 1875 6 (18 Stat. 335), held uncon

stitutional in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, the

question arises whether the right to equal enjoyment

of such facilities must be deemed excepted from the

coverage of the 1866 Act.

1. At the outset, we stress that there can be little

doubt that the draftsmen o f the 1866 Act believed

they were reaching places of public accommodation.

The 39th Congress, which passed the First Civil

Rights Act and framed the Fourteenth Amendment,

legislated against a background of common law rules

affording members of the public not suffering from

racial disability a legal right to use public convey

ances and to obtain sendee in inns and hotels. See,

e.g., Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding

of “ Equal Protection of the Laws,” 50 Coluni. L.

Rev. 131, 149-153; Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3,

37-43 (Harlan J., dissenting); Bell v. Maryland, 378

U.S. 226, 295-299 (Goldberg, J., concurring). Ac

cordingly, it may be supposed that the declaration

of citizenship and of the right to make and enforce

contracts in Section 1 o f the Civil Rights Act was

meant, at the least, to confer on Negroes the “ same

6 In speaking o f the Civil Eights Act o f 1875 we refer to

Sections 1 and 2, which dealt exclusively with places o f public

accommodation. Section 4 o f the Act, outlawing racial discrim

ination in jury selection, was vindicated in Ex Parte Virginia,

100 U.S. 339, and is today codified as 18 U.S.C. 243. Sections

3 and 5 were jurisdictional provisions, presumably applicable to

the whole of the Act.

16

right” to the services of public accommodations as

white citizens had enjoyed. Compare Ferguson v. Gies,

82 Mich. 358, 365; Donnell v. State, 48 Miss. 661.

Indeed, opponents of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and

the Civil Rights Act argued, without contradiction,

that those measures would afford Negroes the right

to equal treatment in places o f public accommoda

tion. See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 541, 936;

id. App. 70, 183 (Representatives Dawson and Rous

seau, Senator Davis) ; Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392

U.S. at 433, 435 n. 68. Presumably, the proponents of

the Act offered no denial because they recognized that

this was, indeed, one inevitable consequence of grant

ing Negroes equality before the law, even in the nar

rowest sense. See Coger v. North West. Union Packet

Co., 37 Iowa 145 (1873) ; Flack, The Adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment 11-54 (1908). See also Sup

plemental Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae, Nos. 6, 9, 10, 12, and 60, O.T. 1963, pp.

119-130.

This reach of the 1866 Act was made clearer by the

re-enactment of the measure in 1870, after the adop

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment, which had

confirmed the grant of citizenship to Negroes and

explicitly guaranteed “ equal protection of the laws.”

See Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392 U.S. at 436-437.

That understanding is reflected in the protracted con

gressional debates on the proposals which culminated

in the Civil Rights Act of 1875, debates premised on

the same concept of “ civil” rights which underlay

the declaration of rights in the 1866 Act. See Cong.

Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 381-383 (Senator

Sumner) ; Gressman, The Unhappy History of Civil

17

Mights Legislation, 50 Mich. L. Rev. 1323-1336. There

was, indeed, specific reference to an existing duty

to afford Negroes equal treatment in places of public

accommodation. As the Chairman of the House Judi

ciary Committee, Representative Butler of Massa

chusetts, told his colleagues, the bill which ultimately

was enacted as the Civil Rights Act of 18757—

* * * gives to no man any rights which he has

not by law now, unless some hostile State stat

ute has been enacted against him. He has no

right by this bill except what * * * every

man * * * has by the common law and civil

law of the country.

2. The question remains: I f freedom from racial

discrimination in places of public accommodation was

already a federal right—secured by the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, re-enacted in 1870—why then did Con

gress address itself to the subject again in 1875?

W e might simply offer the short answer given for

the Court by Mr. Justice Holmes in United, States v,

Mosley, 238 U.S. 383, 387, rejecting the argument that

18 IT.S.C. 241 should not be read as reaching interfer

ence with voting rights because they were specifically

dealt with elsewhere: “ Any overlapping that there

may have been well might have escaped attention,

or if noticed have been approved.” Redundancy is not

rare in legislation of the period. See, e.g., the overlap

of Sections 241 and 242 of the Criminal Code as ap

plied to rights protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment, noticed in United States v. Williams, 341 U.S.

70, 78 (opinion of Frankfurter, J .), 88 n. 2 (opinion

o f Douglas, J .), and condoned in United States v.

T 2 Cong. Rec. 340.

18

Price, 383 U.S. 787, 800-806, 802 n. 11. This may be

no more than another instance of duplication. But

there is another explanation for the Civil Rights

of 1875.

It is most likely, we think, that the 1875 law was

enacted not to afford a new guarantee of equality in

public accommodations, but to provide a more effec

tive means, through federal enforcement, of vindicat

ing rights which already had been recognized. The

1866 law provided no specific civil remedy for viola

tion of the rights enumerated in Section 1, and its

criminal provisions were applicable only to conduct

done “ under color of law.” See Section 2 of the Act,

now 18 U.S.C. 242. Negroes who were denied equal

treatment in places of public accommodation were

thus forced to seek redress under State law or through

the uncertain remedies which might be available in

the federal courts. See Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392

U.S. at 414 n. 13. The debates on the 1875 law dem

onstrated an awareness of the need for more effective

enforcement of the right: “ the remedy is inadequate

and too expensive, and involves too much loss of time

and patience to pursue it. When a man is traveling,

and far from home, it does not pay to sue every inn

keeper who, or railroad company which, insults him

by unjust discrimination” (2 Cong. Rec. 4082 (Sen

ator Pratt)).

The congressional response to this problem was the

dramatically enlarged federal role assumed by Sec

tion 2 of the 1875 Act. Although earlier laws had con

fined criminal penalties for interference with civil

rights (other than voting) to official conduct or con

spiracies, Section 2 made it a federal offense (a mis

19

demeanor) for any person, even aeting privately and

alone, to deny equal treatment in public accommoda

tions. And Section 3 directed federal officials to ini

tiate prosecutions under the Act. Section 2 also pro

vided for a fixed penalty of $500 which the aggrieved

person could recover from the violator in a civil

action exclusively in a federal court. In short, the

apparent purpose and effect of the Civil Eights Act

of 1875 was to focus particularly on one of the many

rights secured by the 1866 Act which was appropri

ate for especially stringent federal enforcement. That

is, of course, a fully adequate basis for the enactment

of supplementary legislation.

D. THIS COURT’S DECISION IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS CASES. IS NOT A

A question remains whether the decision in the

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, does not foreclose our

conclusion that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 outlaws

racial discrimination in places of public accommoda

tions. There are two possible difficulties: the first

premised on the holding that the Act of 1875 was un

constitutional ; the second on the distinction drawn in

the opinion between the 1875 Act and the Civil Rights

Act of 1866.

1. Insofar as the Civil Rights Cases denied the

power o f Congress under the Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendmer' '

it plain that the authority of that ruling has been

eroded by later decisions. The underlying premise of

the Fourteenth Amendment holding in the Civil

Rights Cases—that legislation enforcing the Equal

Protection Clause can only reach discriminatory con

VIABLE OBSTACLE TO OUR CONCLUSION

privately owned

20

duct by persons invoking the shield o f State law—was

rejected by a majority of the Court in United States

v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 762 (Clark, J., concurring),

781-784 (opinion of Brennan, J .) . But, for present pur

poses, it is enough to notice that the narrow view taken

in the Civil Rights Cases with respect to congressional

power under the Thirteenth Amendment is inconsistent

with Jones v. Mayer Co., stipra.

W e recognize that the Court in Jones did not, in

terms, overrule the Thirteenth Amendment holding

o f the Civil Rights Cases, there being no occasion to

confront the ruling directly. See 392 U.S. at 441 n.

78. But the Court did expressly hold that Section 2

o f the Thirteenth Amendment authorizes legislation

which does more than merely restore legal capacity

to former slaves. Thus, it was stated that “ Congress

has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment ra

tionally to determine what are the badges and the

incidents of slavery, and the authority to translate

that determination into effective legislation” (392

U.S. at 440). Accordingly, the Court expressly over

ruled Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1, a decision

holding—on the authority o f the Civil Rights Cases—

that Section 1981 could not validly bar racial dis

crimination affecting a contract of employment (392

U.S. at 441-443 n. 78). And, in language fully appli

cable here, the Court broadly held (392 U.S. at 443) :

Negro citizens North and South, who saw in

the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of free

dom—freedom to “ go and come at pleasure”

and to “ buy and sell when they please” —would

be left with “ a mere paper guarantee” if Con

gress were powerless to assure that a dollar in

21

the hands of a Negro will purchase the same

thing as a dollar in the hands o f a white man.

At the very least, the freedom that Congress is

empowered to secure under the Thirteenth

Amendment includes the freedom to buy what

ever a white man can buy, the right to live

wherever a white man can live. * * * [Notes

omitted.]

The thrust o f the Jones opinion, we submit, is that

it is not “ running the slavery argument into the

ground” —as the majority in the Civil Bights Cases

supposed (109 U.S. at 24)—to concede congressional

power to attempt to eradicate the vestiges of the

slave system wherever they persist in the public life

of the community. Whatever the validity in 1883 of

viewing admission to places of public accommodations

as a mere matter of “ social rights” (109 U.S. at 22)

and characterizing the discriminatory exclusion by

the proprietor as involving only a discretionary deci

sion “ as to the guests he will entertain” (109 U.S. at

24), that approach does not conform to the present

reality. Cf. the opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas, con

curring, in Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 245-246,

252-283. In light o f the old common law obligation,

imposed on at least some operators of public accom

modations, it is difficult to appreciate that the privilege

of obtaining entry and service without arbitrary dis

crimination was ever a mere “ social” matter. But, at

all events, it is today more properly deemed a “ civil

right.” Cf. Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States,

379 U.S. 241, 251. In sum, we believe the constitu

tional power of Congress under the Thirteenth

Amendment to reach racial discrimination in modern

22

places of public accommodations is no longer open to

doubt.

2. We have already elaborated our view that the

Congress o f 1866 meant to outlaw the kind of dis

crimination revealed by this record. Even assuming

the constitutionality o f such an effort, however, the

Civil Rights Cases may be invoked as apparently

reaching the opposite conclusion, as a matter of stat

utory construction.

The objection, once again, is largely answered by

the decision in Jones v. Mayer Co. Insofar as the pre

vailing opinion in the Civil Rights Cases characterizes

the Civil Rights Act of 1866—in contrast to the Act

o f 1875—as merely removing legal “ disabilities” (see

109 TI.S. at 22), without in any way controlling the

freedom of sellers to discriminate on racial grounds,

that view has been squarely rejected by the Court.

E.g., 392 U.S. at 418AL19, 436. And there is no better

reason to accept the apparently equally narrow view

of the “ contract” clause espoused in that opinion. We

add only that, assuming Section 1981 can properly be

read as impliedly exempting certain pei*sonal trans

actions, and assuming further there was once a basis

for considering the purchase of entry to a place of

amusement as a purely “ private” contract outside

the scope of the provision, present circumstances

would now justify treating such a transaction as a

covered “ public” contract.

E. THE PUBLIC ACCOMMODATIONS LAW 0|" 1964 DOES NOT AFFECT

THE COVERAGE OF THE 18 66 ACT

One final objection suggests itself: that enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of that year (42 II.S.C. 2000a

et seq.), in some way supersedes the provisions of the

23

1866 Act insofar as they deal with the same subject

matter. Here, too, Jones v. Mayer Co. indicates the

answer in rejecting a comparable argument premised

on an interpretation of the Pair Housing Title of the

Civil Act of 1968 (42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq.) as repeal

ing or qualifying the “ property” provision of the

1866 statute.

1. Of course, the Understanding of the legislators o f

1964 as to the intent of their predecessors a Century

earlier is only very remotely relevant. Certainly, it

cannot override the clear indications given in 1866

and in 1875 that the original Civil Rights Act reached

places of public accommodations. Accordingly, just as

the Court did not look to the drafters of the Pair

Housing Law of 1968 to determine the scope Of Sec

tion 1982, here our construction of Section 1981 can-

hot be affected by the views prevailing in the 88th

Congress. Nor is it even important to know what those

views were: whether one assumes that the full scope

of Section 1981 was or was not appreciated in 1964, it

is dear that Title I I o f the Civil Rights Act o f that

year was not intended to repeal or supersede or amend

the old statute.

2. We note first—as the Court did in Jones (392

U.S. at 413-417)—that there are substantial differ

ences between the new law and the old. Title I I of

the 1964 Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of

“ race, color, religion, or national origin” (Section

201(a)), while 42 U.S.C. 1981 presumably is appli

cable only to race or color discrimination. Although

Section 1981, on its face, prohibits all racially moti

vated denials of the right to enter into contracts,

Title I I applies only to certain types of establish

24

ments having some nexus with interstate commerce

(Sections 201(b), 201(c)). Section 1981 is couched

in declaratory terms, without reference to any par

ticular mode of enforcement, whereas Title II embod

ies a specific remedy provision (Section 204(a)).

Significantly, the new law—unlike the old—-expressly

provides for enforcement at the instance of the

Attorney General (Section 206), and the 1964 Act

also created a Community Relations Service to assist

in the private settlement of disputes relating to dis

criminatory practices (Title X , Sections 1001-1004,

42 U.S-C. 2000g-2000g-3) to which the courts may

refer cases brought under Title I I for the purpose of

achieving voluntary compliance (Section 204(d)).

In many respects the differences are comparable

to those between Section 1982 and the 1968 housing

law which the Court noticed in Jones. Here, too, the

old law is “ a general statute applicable only to racial

discrimination * * * and enforceable only by pri

vate parties acting on their own initiative,” while

the new legislation is a “ detailed” and specialized

enactment “ enforceable by a complete arsenal of fed

eral authority” (392 U.S. at 417). Accordingly, if

we assume that the Congress of 1964 recognized the

vitality and applicability of the Civil Rights Act o f

1866—an assumption apparently indulged by the

Court in Jones with respect to the drafters of the

1968 housing law—Title I I can properly be viewed

as special supplementary legislation, replacing the

nullified Act o f 1875, but leaving Section 1981

untouched.

3. It may be objected that our conclusion is sound

only insofar as it focuses on those provisions of Title

25

I I which add substantive guarantees or remedial

machinery and ignores the fact that the new law in

some respects retrenches on the broad coverage of

Section 1981. The answer is that, confronted with

the same situation with respect to the 1968 housing

law, the Court in Jones did not on that account find

a pro tanto repeal of Section 1982. The same result

is compelled here.

There are of course many possible explanations-

for the limitations of the 1964 Act. Some were merely

responsive to the Commerce Clause approach of the

legislation and then prevailing constitutional doubts

concerning the scope of congressional power under

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. Most

likely, the full reach of Section 1981 in this area was

not then appreciated.8 But it does not follow that

Section 1981 was repealed sub silentio. On the con

trary, Title I I expressly preserves pre-existing rights

under federal law and that provision must of course

be honored whether or not it was then recognized

that Section 1981 was an operative statute with re

spect to public accommodations. Cf. Jones v. Mayery

supra, 392 U.S. at 437.

4. The savings clause is as follows (Section 207(b )

of the Act, 42 U.S.C. 2000a-6(b)) :

8 42 U.S.C. 1981 and 1982 were briefly noted in the hearings'

on the Civil Rights Act as at least prohibiting State-sanctioned'

discrimination in places o f public accommodation (Hearings on

S. 1732 before the Senate Committee on Commerce, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess., p. 134 (Senator Prouty and Attorney General Ken

nedy) ). It does not appear, however, that Congress understood

those infrequently-used statutes to have the reach which has

been confirmed by this Court’s construction of 42 U.S.C. 1982’

in Jones.

26

* * * [N] othing in this title shall preclude any

individual or any State or local agency from

asserting any right based on any other Federal

or State law not inconsistent with this title,

including any statute or ordinance requiring

nondiscrimination in public establishments or

accommodations, or from pursuing any remedy,

civil or criminal, which may be available for

the vindication or enforcement of such right.

It will be noticed that only rights under laws “not

inconsistent” with Title I I remain enforceable. That

is no obstacle here, however. To the extent that Sec

tion 1981 prohibits racial discrimination by establish

ments which are not covered by Title II, it is not

“ inconsistent” with the 1964 Act in the ordinary

sense that it contradicts the basic purpose o f the new

law; it obviously is designed to vindicate the same

right. Moreover, the reference to State statutes and

local ordinances makes it clear that a law with a more

generous coverage was not “ inconsistent” in the sense

used here. For it goes without saying that Congress

did not intend to invalidate State provisions which

reach places of public accommodation left unregulated

by the new federal law. It would be turning the stat

ute on its head to read into it a purpose to confer on

owners of non-covered establishments a federal right

to practice racial discrimination, notwithstanding

local legislation prohibiting it.

The conclusion that 42 IT.S.'C. 1981, which imple

ments the Thirteenth Amendment, is repealed insofar

as it applies to establishments not covered under Title

I I can rest only on the premise that Congress delib

erately determined in 1964 that the Commerce Clause

was to be the exclusive basis for all federal regulation

27

in respect of racial discrimination in public accom

modations. There is no evidence of any such deter

mination. Cf. United States v. Johnson, 390 U.S. 563,

566-S67.9 Nor is there any other indication that Con

gress meant to repeal the Civil Rights Act of 1866

in this respect. The result is that Section 1981 stands

unimpaired.

II . T H E EXCLUSION OP PETITIONERS, BY REASON OP TH EIR

RACE, FROM T H E E N JO Y M E N T OP T H E FACILITIES OP

LAK E N IX O N CLUB VIOLATES TITLE II OF TH E CIVIL

RIGHTS ACT OP 1 9 6 4

Section 201(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

IT.S.C. 2000a(a)) guarantees to all persons, “ without

discrimination or segregation on the ground of

race [or] color,” “ the full and equal enjoyment of

the * * * services, facilities, privileges, [and] advan

tages * * * of any place of public accommodations.”

The Act prohibits any person from withholding or

denying the right secured by Section 201, and author

izes an aggrieved party to institute a civil action for

preventive relief (Sections 203(a) and 204(a), 42

U.S.C. 2000a-2(a) and 2000a-3(a)). Both the district

court and the court of appeals held that petitioners

were not entitled to relief under the 1964 Act because

Lake Nixon Club is not a place of public accommo

dation as defined in Section 201. For the following

reasons, however, we conclude that Lake Nixon is

covered under either Section 201(b)(4) or Section

9 We note that onr interpretation o f Section 207(b), since it

relates to the enforcement by individuals o f rights not specifi

cally provided by Title II , is also fully consistent with the posi

tion taken in the dissenting opinion in United States v. John

son, see 390 U.S. at 568 n. 1.

28

201(b)(3) of the Act (42 U.S.C. 2000a(b) (4), 42

U.S.C. 2000a(b)(3)).10

A. SECTION 2 0 1 ( b ) ( 4 ) BRINGS LAKE NIXON W ITHIN THE COVERAGE

OF THE 1964 ACT

In addition to the specific types of establishments

which are covered under Sections 201(b)(1) to 201

(b) (3) if their operations affect commerce, Section

201(b)(4) extends the A ct’s prohibition against dis

crimination to any establishment which has a covered

establishment located on its premises and which holds

itself out as serving the patrons of the covered estab

lishment. Respondent’s testimony at trial showed that

Lake hTixon maintained a snack bar for the con

venience of patrons who used its other facilities.

Thus, if the snack bar operation is covered under

Section 201(b)(2), the entire establishment would

be brought within the coverage of the Act. The dis

trict court held, however, that Section 201(b) (4) was

inapplicable because Lake Mxon was a single enter

prise whose principal business was the furnishing of

recreational facilites, so that the snack bar could not

be considered a separate establishment covered under

the Act (A. 58).

The district court’s ruling misconstrues Section

201(b)(4). Two of the major proponents of the bill

explained to their colleagues in the House and Senate

that a department store or other retail establishment

10 This case does not present any question under the “ private

club” exemption o f Section 201(e) o f the Act (42 U.S.C.

2000a (e ) ). The district court found that Lake Nixon Club,

despite its “ membership” requirement, would not come “ within

the terms o f any rational definition o f a private club which

might be formulated” under Section 201(e) (A . 57), and

respondent did not challenge that finding on appeal.

29

which would not otherwise be covered would have

to open “ all its facilities” on a nondiscriminatory

basis if it contained so much as a “ lunch coun

ter.” Hearings on H.R. 7152 before the House

Committee on Rules, 88th Cong., 2d Sess., 92 (Repre

sentative Celler); 110 Cong. Rec. 7406-7407 (Senator

Magnuson). See also H. Rep. Ho. 914, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess., p. 20. In Fazzio Beal Estate Go. v.

Adams, 396 F. 2d 146 (C.A. 5), affirming 268 F.

Supp. 630 (E.D. La.), the court of appeals enun

ciated the correct principle in holding that a refresh

ment counter located within a bowling alley could be

considered a separate establishment itself covered

under the Act for the purpose of applying Section

201(b)(4) to the entire establishment (396 F. 2d at

149) :

It is clear that the Act, for purposes of cover

age, contemplates that there may be an “ estab

lishment” within an “ establishment.”

* * * [ I ] f it be found * * * that a covered

establishment exists within the structure of a

unified business operation, then under the pro

visions of § 201(b) (4) of the Act the entire

business operation located at those premises

becomes a “ covered establishment.” The Act

draws no distinction with regard to the prin

cipal purpose for which a business enterprise

is carried on.11

11 Accord, Scott v. Young, 12 Eace Eel. L. Eep. 428 (E.D.

Va.) (recreational area-eating facility ); Evans v. Laurel Links,

Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E.D. Va.) (golf course-eating facility );

United States v. All Star Triangle Bowl, Inc., 283 F. Supp.

300 (D. S.C.) (bowling alley-eating facility ); United States v.

Fraley, 282 F. Supp. 948 (M.D. N.C.) (tavern-eating facility );

30

See Hamm v. City of Rock Mill, 379 U.S. 306, 309,.

where this Court held that a lunch counter in a de

partment store which was operated as an adjunct to

the main business of the store was a covered establish

ment within the contemplation of the Act.

There is no doubt on this record that the Lake

Nixon snack bar is a “ facility principally engaged in

selling food for consumption on the premises” under

Section 201(b)(2) (A. 32; see Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., 377 F. 2d 433 (C.A. 4) (en

bane), modified as to other issues and affirmed, 390

U.S. 400). It is a covered establishment if its opera

tions affect commerce, i.e., if it “ serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers or a substantial portion o f

the food which it serves * * * has moved in com

merce” (Section 201 (c)(2 )). The court of appeals

held that the Lake Nixon snack bar failed to satisfy

either standard (A. 74-78).

In our view, the record establishes that the Lake

Nixon Club (which, for this inquiry, is congruent with

its snack bar) “ offers to serve interstate travelers”

within the meaning of Section 201(c)(2 ).12 The court

United States v. Beach Associates, Inc., 286 F. Supp. 801 (D.

Md.) (battling beach-eating facility and tourist cottages). See

also Drews v. Maryland, 381 U.S. 421, 428 n. 10 (Warren, C.J.,

dissenting-), and Judge Heaney’s dissent in the instant case

(A . 82-86). Compare Nesmith v. YMGA of Raleigh, 397 F.

2d 96, 100 (C.A. 4) (dictum).

12 On this analysis, it is unnecessary to consider whether a.

substantial portion o f the food or its ingredients moved in

commerce. However, we note that the district court took judicial

notice that the principal ingredients o f the bread products used

and some ingredients in the soft drinks probably originated

outside o f Arkansas (A. 57). The use o f the word “ substan

tial” in the statute was intended to mean only that something

“more than just [a] minimal,” or more than a ude minimis”

amount of the food had moved in commerce. See Hearings on

31

of appeals relied on the district court’s finding that

“ there was no evidence that the Lake Nixon Club has

ever tried to attract interstate travelers as such” (A.

74, 56, emphasis added). But we can find nothing in

the legislative history of the Act to indicate that the

“ offers to serve” provision was intended to mean less

than what it says and to apply only to those establish

ments which actively solicit the business of interstate

travelers. Such a limited construction was implicitly

rejected by this Court in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306, 309, where, although coverage under the

Act does not appear to have been seriously disputed,

the Court found an offer to serve interstate travelers

in the fact that the lunch counter was located in a

retail store that “ invites all members of the public into

its premises to do business.” In Gregory v. Meyer, 376

F. 2d 509, 510 (C.A. 5), the court, in finding that a

restaurant offered to serve interstate travelers,

stressed the fact that “ customers were not questioned

as to tourist status, and that tourists were not rejected

as customers.” See also Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632,

140 S.E. 2d 866. And in Wooten v. Moore, 400 F. 2d

239, 242 (C.A. 4), the court cited a restaurateur’s

“ readiness to serve white strangers without interroga

tion concerning their status” as evidence that he

offered to serve interstate travelers, notwithstanding

the fact that he had posted a sign on the door stating

Civil Rights before Subcommittee No. 5 o f the House Committee

on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., Part II , pp. 1384, 1386

(Attorney General Kennedy); Hearings on S. 1732 before the

Senate Committee on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 172,

212 (Attorney General Kennedy and Assistant Attorney Gen

eral Marshall); 110 Cong. Rec. 4856 (Senators Humphrey and

Sparkman); 'Willis v. Pickrick Restaurant, 231 F. Supp. 396, 403

(N.D. Ga.), appeal dismissed, 382 U.S. 18; Greqory v. Meyer.

376 F. 2d 509, 511 (C.A. 5).

32

that the restaurant did not “ eater to interstate

patrons.”

In the present case, the district court found that

Lake Nixon was “ open in general to all of the public

who are members of the white race” (A. 57). When

questioned about his admission policies at trial, re

spondent did not advert to any policy of excluding

interstate travelers or any practice of questioning

patrons to determine whether they were out-of-state

residents (see A. 20-21). And as Judge Heaney noted

in his dissent below (A. 88 n. 9), respondent’s adver

tisements did not suggest that interstate travelers

would not be admitted; nor did the membership cards

require an applicant to state his address. In addi

tion, respondent inserted advertisements for Lake

Nixon in periodicals which were intended to reach

interstate travelers: the “ Little Rock Air Force

Base,” a monthly newspaper published at the base,

and “ Little Rock Today,” a monthly magazine list

ing available attractions in the Little Rock area (A.

55-56; see petitioners’ Petition for Rehearing en banc

in the court below, A. 92, 96, which quotes from the

masthead of the May 1968 edition of “ Little Rock

Today” : “ Published monthly and distributed free o f

charge by Metropolitan Little Rock’s leading

hotels * * * motels and restaurants to their guests,

new comers and tourists * * *.” ). Although these ad

vertisements were directed to “ members” of Lake

Nixon, there is little reason to assume, as Judge

Heaney realistically observed, that travelers would be

less likely than residents of the Little Rock area to

understand that the “ membership” device was used

33

solely to exclude Negroes from the publicly adver

tised facilities (A. 89).

The fact that Lake Nixon, unlike the restaurants

in Gregory and Wooten, is not located on an inter

state highway does not justify disregarding the other

evidence that respondent offered to serve interstate

travelers. Lake Nixon is not “ some isolated and re

mote lunchroom” (Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United

Slates, 379 U.S. 241, 275 (concurring opinion of Mr.

Justice Black)) which Congress’ regulatory power

under the Commerce Clause could reach only with

evident strain. It is a large and profitable establish

ment which, Mrs. Paul testified, serves about 100,000

patrons each season (A. 43). An offer to serve such

a large segment of the public without inquiry as to

the residence o f customers, under circumstances which

make it reasonable to assume that some interstate

travelers have accepted the offer, constitutes a suffi

cient connection with interstate commerce to support

coverage of the establishment under Sections

201(b) (2) and 201(c) (2). See Hamm v. City of Bock

Hill, 379 U.S. 306. Here, the offer to serve and the like

lihood of actual service were so clear that the district

court stated that “ it is probably true that some out-

of-state people spending time in or around Little

Rock have utilized [Lake Nixon’s] facilities” (A. 57).

In the light of the foregoing appraisal of the evi

dence, the failure of both courts below to find that

the Lake Nixon snack bar offered to serve interstate

travelers reflects an unduly restrictive construction of

Section 201(c)(2) which deprives the Act of its in

tended scope. We conclude that the evidence demon

34

strated that the snack bar was a covered establishment

under Section 201(b)(2) and 201(c)(2) and, conse

quently, that the entire Lake Nixon Club was covered

under Section 201(b )(4 ).13

B. SECTION 2 0 1 ( b ) ( 3 ) BRINGS LAKE NIXON W ITHIN THE COVERAGE

OF THE 1964 ACT

Taken together, Sections 201(b)(3) and 201(c)(3)

include within the A ct’s proscription of discrimina

tion “ any motion picture house, theater, concert hall,

sports arena, stadium, or other place of exhibition

or entertainment” which “ customarily presents films,

performances, athletic teams, exhibitions, or other

sources of entertainment which move in commerce.”

The district court rejected petitioners’ claim for relief

under Section 201(b)(3) on the ground that the

13 Though a decision reversing and remanding on the basis of

Section 201 (b) (4) would dispose of this case, we note that an

order grounded only upon that section may be circumvented

by respondent i f he is prepared to remove all vestiges o f the

eating facility from the Lake Nixon premises. W e stress, how

ever, that mere closing o f the eating facility at any time prior

to the entry o f an order by the district court upon remand

should not be sufficient ground for dismissing the action as

moot. The closing o f the snack bar at this date would be for the

purpose o f defeating coverage. So long as the facilities for pre

paring and serving food remain on the premises they may be

opened and put into use. Thus, unless the entire snack bar and

all its facilities are totally removed from the Lake Nixon prem

ises, the case could not be rendered moot under Section

201(b) (4). Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 376; United States v.

All Star Triangle Bowl, Inc., 283 F. Supp. 300, 302-303

(D. S .C .); United States v. Beach Associates, Inc., 286 F.

Supp. 801, 808 (D. M d.). Yet., respondent might well choose to

take that step. Therefore, a determination o f coverage under

Title I I should not in this case be rested upon Section

201 (b) (4) alone.

35

“ other place[s] of * * * entertainment” covered by

the statute included only establishments where pa

trons were “ edified, entertained, thrilled, or amused

in their capacity of spectators or listeners” (A. 59).

Alternatively, the court held that even if Lake Nixon

were considered a place of entertainment, its opera

tions did not affect commerce under Section 201

(e) (3) because the juke boxes, records, boats, and

other amusement apparatus which respondent ob

tained from outside the State were no longer moving

in interstate commerce (A. 61-62). The majority on

the court of appeals affirmed, substantially on the

grounds stated by the district court (A. 78-79, 81).

The decisions below are in conflict with the decision

of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit en

banc in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394

F. 2d 342, which reversed the ruling of a divided

three-judge panel (391 F. 2d 86) that Section 201

(b) (3) did not cover a private amusement park

which offered mechanical rides and an ice skating

rink to white patrons. The full court held that a place

of entertainment within the meaning of Section 201

(b )(3 ) included “ both establishments which present

shows, performances and exhibitions to a passive au

dience and those establishments which provide rec

reational or other activities for the amusement or

enjoyment of its patrons” (394 F. 2d at 350). The

court also concluded that “ sources of entertainment”

within Section 201(c)(3) include the equipment and

apparatus used by the patrons of such an establish

ment, as well as the patrons themselves, who provide

entertainment for those who come only to watch others

36

enjoy the park’s facilities (id. at 349, 351). The

court further held that the use of the term “ move

in commerce” in Section 201(c)(3) was not intended

to exclude sources of entertainment, such as equip

ment, which had moved in interstate commerce but

which had come to rest on the premises of the enter

tainment establishment {id. at 351-352).

In a lengthy memorandum submitted at the request

of the panel which rendered the initial decision in

Miller (printed as an appendix to the panel’s opin

ion, 391 F. 2d 86, 89-96), the government analyzed

the relevant portions of the legislative history o f Sec

tions 201(b) (3) and 201(c) (3) and advised the court

that the history was “ inconclusive” as to the question

whether Congress intended to restrict coverage under

those sections to places which offer performances for

spectator audiences. We believe that is a correct

statement. But it does not follow that the scope of

the provision should be limited to what Congress

undoubtedly meant to encompass. On the contrary,

in the absence of a discernible legislative intent to

restrict coverage to a certain class of entertainment

facilities, we think the full court of appeals on re

hearing in Miller correctly determined to give full

effect to the statutory language according to its com

mon understanding, so as not “ to deprive citizens

of the United States of the general protection which

on its face [the statute] most reasonably affords” —

to borrow the language of Mr. Justice Holmes, speak

ing for the Court in a related context {United States

v. Mosley, 238 U.S. 383, 388). See also United States

v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 801; United States v. Johnson,

37

390 U.S. 563, 566-567; Jones v. Mayer Go., 392 U.S.

409, 421, 437; Amos v. Prom, Inc., 117 F. Supp. 615,

624 (H.D. Iowa).

To carve from Section 201(b)(3) an exception for

Lake Hixon and similar establisliments would violate

the overriding purpose of Title I I : “ to remove the

daily affront and humiliation involved in discrimina

tory denials of access to facilities ostensibly open to

the general public.” H. Rep. Ho. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess., p. 18. See Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United

States, supra, 379 U.S. at 245-246, 291-292 (Goldberg,

J., concurring) ; Hamm v. City of Bock Hill, supra,

379 U.S. at 315-316. We turn, then, to the statutory

words which the courts below construed narrowly:

“ entertainment” in Section 201(b)(3) and “move” in

Section 201(c) (3).

1. The dictionary defines “ entertainment” as “ the

act of diverting, amusing, or causing someone’s time

to pass agreeably: [synonymous with] amusement”

(Webster’s Third Hew International Dictionary 757).

Ho distinction is made between that which amuses or

diverts one as a spectator or as a participant. Rec

reational activities such as swimming, boating, minia

ture golf, picnicking, and dancing—all offered at Lake

Hixon—unquestionably amuse, divert, or agreeably

engage a participant’s attention; so also may sun

bathing on a beach or watching others engage in the

activities available at Lake Hixon. Indeed, respondent

himself advertised over a local radio station that

“ Lake Hixon continues their policy of offering you

year-round entertainment” (A. 88 n. 10).

Absent a clear showing that Congress intended to

exclude establishments which offered such diversions

38

to tiie general public, to bold that the Lake Nixon

Club is not a place of entertainment within the mean

ing of Section 201(b)(3) would violate the basic

canon of statutory construction that the words of a

law are presumed to be used in their ordinary and

usual sense. Moreover, the facts o f this case illus