Smith v USA Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 2000

108 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v USA Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 2000. 3adcadcd-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/769f2f24-a843-4df4-87b7-d5fcd9155de7/smith-v-usa-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

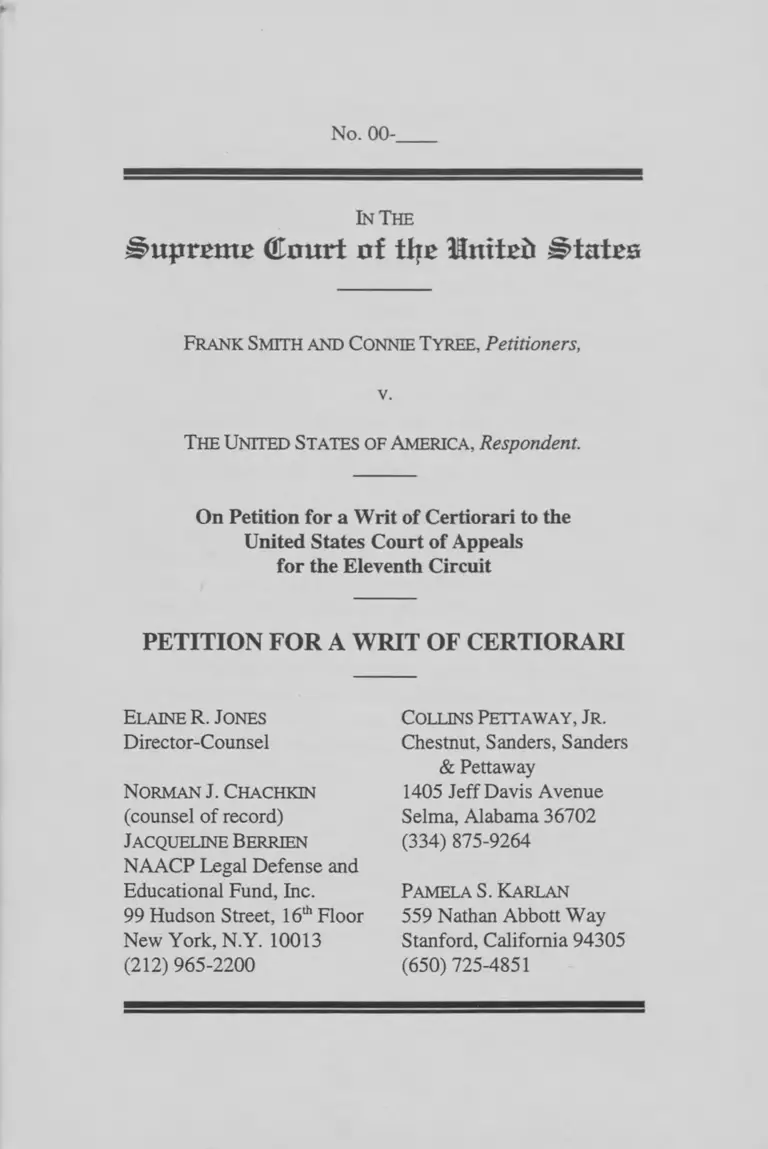

In The

#upm ue Court of tljr timtrii sta tes

Frank Smith and Connie Tyree, Petitioners,

v.

The United States of America, Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

(counsel of record)

Jacqueline Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 965-2200

Collins Pettaway, Jr .

Chestnut, Sanders, Sanders

& Pettaway

1405 Jeff Davis Avenue

Selma, Alabama 36702

(334) 875-9264

Pam elas . Karlan

559 Nathan Abbott Way

Stanford, California 94305

(650) 725-4851

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the Court of Appeals flout the “ordinary equal

protection standards” applicable to claims o f selective

prosecution identified in United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S.

456, 465 (1996), when it:

a. imposed a requirement that petitioners prove

discriminatory purpose and discriminatory effect by “clear

and convincing evidence” rather than by the

preponderance o f the evidence standard applied by other

Circuits?

b. adopted a definition o f “similarly situated

individuals” that eviscerates the Constitutional protection

recognized in Armstrong by “mak[ing] a selective-

prosecution claim impossible to prove,” 517 U.S. at 466?

2. Were petitioners’ convictions improperly sustained by

the Court o f Appeals when it held, in conflict with the

interpretation o f 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973i(c) and 1973i(e) applied

by other Circuits, that these criminal provisions o f the Voting

Rights Act do not require the government to prove lack o f

voter consent in cases involving absentee ballots?

3. Did the Court of Appeals depart so fundamentally

from the accepted course of judicial proceedings as to warrant

correction by this Court when it blatantly ignored the plain

language o f the Sentencing Guidelines provision applicable to

voting-related offenses?

4. Did the Court of Appeals sanction the violation o f

petitioner Tyree’s Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights in

approving the government’s trial strategy o f “effectively

d riv ing a] defense witness off the stand,” Webb v. Texas, 409

U.S. 95, 98 (1972), by threats o f peijuiy prosecution both at

the pre-trial hearing on petitioners’ selective prosecution claim

and at trial?

i

5. Did the Court o f Appeals err in approving the trial

court’s admission o f inherently prejudicial evidence regarding

petitioner Tyree’s witnessing o f other absentee ballots about

which the government conceded that it had no evidence of

wrongdoing, as probative on the conspiracy count?

n

LIST OF ALL PARTIES TO THE

PROCEEDING BELOW

The names o f all parties to the proceeding below are

included in the caption to this Petition.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ............................................................ i

Parties to the Proceeding Be l o w ................................. iii

Table of Authorities ....................................................... vi

Note on Citations to the R e c o rd .................................... xi

Opinions Be l o w ....................................................................... 1

Jurisdictio n ................................................................................ 1

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions In v o l v e d ..................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ..........................................................2

A. The Decision to Prosecute the Petitioners ................ 3

B. The Selective Prosecution C la im ..................................4

C. The Trial ..........................................................................6

D. Petitioners ’ Sentencing ............................................ 11

E. The Court o f Appeals' Opinion ............................... 11

1. Selective Prosecution ........................................ 11

2. Lack o f Voter Consent ...................................... 14

3. Exclusion o f Hutton Testimony......................... 15

4. Calculation o f the Base Offense Level

Under the Sentencing Guidelines ....................... 15

5. Admission o f evidence about Tyree’s

witnessing other ballots .................................... 16

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT ..................16

I. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to

Clarify the Standards to be Applied to

Claims of Selective Prosecution and to

Resolve a Conflict With Both this Court’s

Decisions and Those of Other Circuits ..................16

A. The Eleventh Circuit’s Imposition

of the “Clear and Convincing

Evidence” Standard Conflicts

with this Court’s Decisions and

the Decisions of Other Courts

of Appeals ............................................................. 17

B. The Standard Adopted Below for

Identifying “Similarly Situated”

Individuals When Adjudicating

a Selective Prosecution Claim

Departs Dramatically from Prior

Caselaw and Forecloses the Claim

as a Practical Matter ............................................20

II. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to

Resolve a Conflict Among the Circuits Over

the Construction of Two Criminal Provisions

of the Voting Rights Act ............................................22

III. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to

Address the Proper Application of the

Sentencing Guidelines to the Offenses

with which Petitioners Were Charged ...................... 25

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

IV. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to

Restore the Protections of the Fifth and

Sixth Amendments to Petitioner Tyree ..................27

V. The Court Should Grant Review to Resolve

the Conflict Between the Decision Below and

Rulings of other circuits that Inherently

Prejudicial Evidence of Similar Acts by a

Criminal Defendant May Be Admitted Only

if the Acts are Shown to be U n law fu l......................28

Conclusion .............................................................................30

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Allentown Mack Sales & Service v. N.L.R.B.,

522 U.S. 3 5 9 (1 9 9 8 ) ......................................................... 18

Anderson v. United States,

417 U.S. 211 (1 9 7 4 ) ......................................................... 26

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous. Dev. Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1 9 7 7 ) ......................................................... 18

Attorney General v. IN AC,

530 F. Supp. 241 (S.D.N.Y. 1981), aff’d

668 F.2d 159 (2d Cir. 1982), cert, denied,

459 U.S. 1 1 7 2 (1 9 8 3 )....................................................... 22

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Cases (continued):

Page

Cases (continued):

Attorney General v. Irish People, Inc.,

684 F.2d 928 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 8 2 ) ....................................... 22

Chapman v. United States,

500U .S .453 ( 1 9 9 1 ) .................................................. 26 ,27

Chemical Foundation, Inc. v. United States,

272 U.S. 1 ( 1 9 2 6 ) .................................................. 17n-18n

Eagleston v. Guido,

41 F.3d 865 (2d Cir. 1994), cert, denied,

516 U.S. 808 (1 9 9 5 ) ....................................................... 19

Hadnott v. Amos,

394 U.S. 358 (1 9 6 9 ) ............................................................2

Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222 ( 1 9 8 5 ) ....................................................... 20

Jacobs v. Seminole County Canvassing Board,

No. SC00-2447, 2000 Fla. LEXIS 2404

(Fla. Dec. 12, 2000) ......................................................... 24

Jones v. Plaster,

57 F.3d 417 (4th Cir. 1995) ........................................... 19

Magouirkv. Warden,

No. 99-30594 (5th Cir. Jan. 15, 2001) ......................... 28

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Personnel Adm ’r v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 2 5 6 (1 9 7 9 ) ....................................................... 18

Smith v. Meese,

821 F.2d 1484 (11th Cir. 1987) ................................. 29n

United States v. Anderson,

933 F.2d 1261 (5th Cir. 1991) ......................................30

United States v. Armstrong,

517 U.S. 4 5 6 (1 9 9 6 ) ........................ i, 11,16, 17,20,21

United States v. Boards,

10 F.3d 587 (8th Cir. 1993), cert, denied,

512 U.S. 1205 (1 9 9 4 ) ..................................................... 23

United States v. Bowman,

636 F.2d 1003 (5th Cir. 1981) ........................................ 26

United States v. Chemical Foundation, Inc.,

5 F.2d 191 (3d Cir. 1925) .......................................... 18n

United States v. Cole,

41 F.3d 303 (7th Cir. 1994), cert, denied,

516 U.S. 826 (1 9 9 5 )....................................................... 23

United States v. Darden,

70 F.3d 1507 (8th Cir. 1995), cert, denied,

517 U.S. 1 1 4 9 (1 9 9 6 )..................................................... 19

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

United States v. Dothard,

666 F.2d 498 (11th Cir. 1982) ...................................... 30

United States v. Gordon,

817 F.2d 1538 (11th Cir. 1987), cert, dismissed,

487 U.S. 1265 (1 9 8 8 ) ................................................. 2 ,24

United States v. Guerrero,

650 F.2d 728 (5th Cir. 1981) ................................. 29, 30

United States v. Hammond,

598 F.2d 1008 (5th Cir. 1979) ......... ............................ 27

United States v. Hogue,

812 F.2d 1568 (11th Cir. 1987) .................................... 24

United States v. Parham,

16 F.3d 844 (8th Cir. 1993) ........................................... 22

United States v. Redondo-Lemos,

955 F.2d 1296 (9th Cir. 1992), appeal after

remand sub nom. United States v. Alcaraz-

Peralta, 27 F.3d 439 (9th Cir. 1994) .................... 18-19

United States v. Salisbury,

983 F.2d 1369 (6th Cir. 1993) ...................................... 23

United States v. Sullivan,

919 F.2d 1403 (10th Cir. 1990) .................................... 30

IX

Page

Cases (continued):

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

United States v. Veltmann,

6 F.3d 1483 (11th Cir. 1993) ......................................... 30

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 2 2 9 (1 9 7 6 ) ......................................................... 18

Washington v. Texas,

388 U.S. 1 4 (1 9 6 7 ) ........................................................... 27

Wayte v. United States,

470 U.S. 598 (1 9 8 5 ) ........................................... 16, 18,20

Webb v. Texas,

409 U.S. 95 (1 9 7 2 ) ............................................... i, 27, 28

Statutes and Rules:

18U.S.C. § 13 ............................................................................ 25

18U.S.C. §371 .............................................................................4

18U.S.C. § 3282 ..................................................................... 6n

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ................................................................. 1

42U .S.C . § 1973i ......................................................................25

42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c) .........................i, 1, 4,14, 22, 23, 24, 25

42 U.S.C. § 1973i(e) ........... i, 1,4, 14, 15, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

x

Page

Statutes and Rules (continued):

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Ala. Code § 17-10-7 ..................................................................4

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 101.62(b) .................................................... 24

Fed. R. Evid. 804(b)(1) ........................................................... 10

Other Authorities:

United States Sentencing Guidelines

Manual § 2H2.1 (1997) ........... 1,11,15-16, 17, 25 ,26

Note on Citations to the Record

The opinions and orders below are reprinted infra in the

Appendix to this Petition and are cited as “A pp .__.” The trial

transcript is cited as “T r .__.” The transcript o f the pre-trial

hearing on the motion to dismiss the indictment on the ground

of selective prosecution is cited as “SP T r .__The transcript

o f petitioners’ sentencing is cited as “Sent. T r .__.”

xi

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioners Frank Smith and Connie Tyree respectfully

pray that a writ of certiorari be issued to review the judgment

o f the United States Court o f Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court o f Appeals, which is reported at

231 F.3d 800, appears infra, in the Appendix to the Petition

(App.) at pages 1 to 38. The Order of the District Court

affirming and adopting the Magistrate’s Report and

Recommendation on the question o f selective prosecution is

not reported; it appears infra at App. 39. The Report and

Recommendation of the Magistrate Judge was not reported. It

appears infra at App. 40 to 60.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court o f Appeals was entered on

October 25, 2000. This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the due process clause o f the Fifth

Amendment, the compulsory process clause o f the Sixth

Amendment, and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. In addition, it involves 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973i(c)

and 1973i(e). Finally, it involves Section 2H2.1 o f the United

States Sentencing Guidelines. Those provisions are reproduced

infra at App. 61 to 63.

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On January 30, 1997, petitioners Frank Smith and Connie

Tyree were charged in a thirteen-count indictment with

offenses alleged to have arisen out o f the Novem ber 8, 1994,

federal and general election in Greene County, Alabama.

Greene County, with a population over 90% black (App.

40-41), has been the site o f fiercely waged, racially polarized

political contests since the passage o f the Voting Rights Act o f

1965, which began the process o f enfranchising its black

citizens (App. 41). The pre-existing white political power

structure resisted the black majority’s pursuit o f political

power in a variety o f ways that have previously required

judicial intervention, including intervention by this Court. See

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358, 362-63 (1969) (finding that

the local probate judge had kept qualified black candidates off

the general election ballot through discriminatory application

o f unprecleared state election laws). See also United States v.

Gordon, 817 F.2d 1538, 1540 (11th Cir. 1987) (finding a

colorable claim of selective federal prosecution o f “members

o f the black majority faction”), cert, dismissed, 487 U.S. 1265

(1988). Today, the rival blocs might be described as, on one

side, a black majority faction affiliated with the Alabam a New

South Coalition, and, on the other, a formally nonpartisan and

biracial group, the Citizens for a Better Greene County

(“CBGC”), founded by political opponents o f the black

majority faction. See App. 42-44.

Absentee voting plays a critical role in Greene County’s

electoral politics. As the Magistrate Judge who conducted the

selective prosecution hearing in this case found, “ [bjecause of

the history o f violence and intimidation associated with efforts

by African-Americans to exercise their vote, m any African-

Americans continued to be uncomfortable going to the polls to

vote, and felt more comfortable voting an absentee ballot in

the privacy of their homes.” The result is a significantly

2

higher rate of absentee voting in Greene County compared to

counties with predominantly white populations. App. 41. In

1994, 1,429 of the roughly 3,800 votes cast in Greene County

were cast absentee. Fewer than 40 o f these were cast by white

voters. App. 42.’

A. The Decision To Prosecute the Petitioners

The 1994 election for the Greene County Commission

was hotly contested. It pitted candidates supported by the

black majority against candidates whose support came from

the Citizens for a Better Greene County. See App. 44. The

investigation that led to this prosecution began even before the

election, when politicians in the anti-New South faction

contacted the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office to complain

about possible voting irregularities. Members o f the black

majority faction also complained, after the election, about

violations committed by their opponents. App. 44-45. Until

October 1995, however, the investigation was essentially

dormant, in part because the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Alabama had impounded all absentee

ballots throughout the state in connection with an unrelated

election dispute. App. 45.

In the fall o f 1995, the Alabama Attorney General’s

Office asked to join the investigation. App. 45. Gregory

Biggs, the same state Assistant Attorney General who was

leading state court voting prosecutions involving

predominantly black Hale and Wilcox Counties, was

designated a “Special Assistant United States Attorney” and

participated in the investigation and trial o f petitioners. App.

40, 46, 51. At the time o f the events below, the district

attorney and Alabama circuit judges with jurisdiction over

‘The Magistrate Judge observed that the small number of

whites who cast absentee ballots paralleled the small proportion of

the county’s population that was white. App. 42 n. 1.

3

Hale and Wilcox Counties were white; the district attorney and

circuit judge with jurisdiction over Greene County were both

African-American. App. 41.

Because absentee ballots must be witnessed by two

individuals under Alabama law (see Ala. Code § 17-10-7),

investigators decided to focus on individuals who witnessed

multiple absentee ballots, narrowing their scrutiny to the

approximately 800 absentee ballots that had been witnessed by

one or more persons who had performed the same function on

more than fifteen ballots. App. 46-47. Among those who had

witnessed a substantial number of ballots were petitioner

Tyree, who had witnessed 166, and several members o f the

opposing political camp, including Rosie Carpenter, who

witnessed approximately 100, Lenora Burks, and Annie

Thomas. App. 46; SP Tr. 990-91.

Ultimately, petitioners were alleged to have acted illegally

with respect to seven of the 1,429 absentee ballots cast in the

1994 general election. Count 1 o f the indictment charged both

petitioners with a conspiracy in violation o f 18 U.S.C. § 371;

Count 2 charged both petitioners with voting more than once

in violation o f 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(e); and Counts 3-13 charged

one or both o f the petitioners with providing false information

for the purpose o f establishing eligibility to vote in violation of

42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c) with respect to the absentee ballots cast

by each of seven Greene County voters.

B. The Selective Prosecution Claim

Petitioners moved to dismiss the indictment on grounds of

selective prosecution. The Magistrate Judge found that

petitioners had made a threshold showing of racial or political

selectivity and as a result, allowed discovery and conducted a

five-day evidentiary hearing. See App. 10-11 n.4.

At the hearing, substantial lay and expert testimony was

presented. The Magistrate Judge found that “[t]he testimony of

4

the [petitioners]’ handwriting expert . . . established that a

number o f other people, aside from the [petitioners], may have

been involved in obtaining forged or fraudulent voter

signatures on absentee ballots.” App. 48-49. The Magistrate

Judge summarized in his opinion the expert’s conclusions that

it was “virtually certain,” “highly probable,” or otherwise

likely that signatures on seventeen voters’ absentee ballots had

been written by neither petitioners nor the voters but by

identifiable individuals whom he named. App. 49-50.

Buttressing this expert opinion regarding the existence of

individuals similarly situated to petitioners was extensive lay

testimony by witnesses who reported that they had contacted

the FBI or the Alabama authorities with complaints about

violations committed by activists in the anti-New South

Coalition bloc but that the investigators had not followed up

on these indications of voting irregularities, or that to the

extent the FBI did investigate allegations made by New South

Coalition members, it did so after the filing o f the selective

prosecution motion in this case, suggesting that the

investigation was conducted for the purpose o f rebutting the

motion. See SP Tr. 419-31. The government responded to

these complaints during the selective prosecution hearing by

insisting that its investigation of the 1994 elections in Greene

County was “ongoing.” E.g., SP Tr. 975-76.

Ultimately, Magistrate Judge Putnam issued a report and

recommendation suggesting that petitioners’ motion be denied.

The linchpin o f his analysis with regard to the “selectivity”

prong was his belief that the mere presence o f similarly

situated but unprosecuted individuals is insufficient:

It is not enough to show simply that the defendant has

been prosecuted and that some other person like him has

not yet been prosecuted. . . . [S]ome are prosecuted

presently, and others will be prosecuted in the future.

App. 54-55. Thus, although it was

5

certainly true that there is evidence in the record

indicating that other people have engaged in fraudulent

absentee-ballot voting activities, including forging voters’

signatures and altering ballots [, w]hat has not been shown

is that these other individuals will never be prosecuted.

App. 57 (emphasis added).2

As for the question o f the government’s motivation, the

Magistrate Judge held that race could not be “a motivating

factor” in the decision to prosecute petitioners because “ [a] 11

of the other [similarly situated] people identified by the defen

dants are themselves African-American, like the defendants.”

App. 58. As for the question o f an impermissible political

motivation, the Magistrate Judge held that the fact that some

similarly situated individuals were members o f neither

petitioners’ faction nor the opposing faction rebutted their

allegation that they had been singled out. App. 59.

The district court adopted the Magistrate Judge’s report and

recommendation in its entirety. App. 39.

B. The Trial

Judge C. Lynwood Smith, Jr. presided over petitioners’ trial,

which lasted from September 8 to September 15,1997. During

jury selection the judge sustained petitioners’ Batson objection

to the government’s peremptory strike o f one black

veniremember and seated the juror; the court also held that the

government had only “tenuous” reasons for two other strikes,

although it declined to find them Batson violations.

2The five-year statute of limitations for offenses arising out

of the 1994 election, 18 U.S.C. § 3282, has now run, and it is

undisputed that the government has never prosecuted a single

white individual nor any individual who is not associated with

the New South Coalition for any irregularities arising out of the

1994 Greene County elections.

6

It was undisputed that one or both o f the petitioners were

involved with each of the seven absentee ballots that were the

subject of the indictment, either as a witness or in filling out

“administrative” information such as the voter’s name, address,

or polling place on the ballot or prior ballot application request.3

As to some, but not all, of the applications or affidavits, there

was testimony that petitioners also provided the voter’s

signature.

The government called as witnesses six o f the voters whose

ballots were at issue. The government did not call the seventh

voter, Shelton Braggs, whose vote was the subject o f Counts 12

and 13 of the indictment.

Each o f the six voters who testified provided some evidence

from which the jury might have concluded that he or she did not

ask petitioners to request or to cast an absentee ballot for the

voter in the 1994 general election. But the government was

forced to rely on several voters’ grand jury testimony because,

on the stand in open court, the voters indicated that they had

consented to the casting of their votes. For example, voter

Michael Hunter testified at trial that he had authorized his

brother’s signing his name on the ballot that he had voted; the

government introduced Hunter’s testimony before the grand jury

to prove lack of consent. Tr. 463-68,479-82. Voter Willie C.

Carter testified at trial that he had given petitioner Smith

permission to submit an absentee application; the government

introduced his testimony before the grand jury to prove lack o f

consent. Tr. 565-67, 573-76.

The government presented no evidence w ith regard to Shel

ton Braggs’ s consent. The government had no known examples

3It is perfectly legal for someone other than the voter to fill

out this “administrative” information; the Circuit Clerk testified

that on occasion, the staff in her office would insert the necessary

information. Tr. 225-26.

7

o f Braggs’s handwriting, and its expert witness testified that

Tyree had not signed Braggs’s absentee ballot application. Tr.

756. The only evidence in the record regarding Braggs was that

he was a registered voter in Greene County who spent most of

his time out o f state and that, during the summer of 1994, he had

been Tyree’s boyfriend and had been living with her. Tr. 877-80.

On the counts relating to voter Sam Powell, Tyree was

prevented from presenting critical evidence by the district court’s

exclusion o f a key witness’s testimony: Burnette Hutton,

Pow ell’s daughter, had appeared, voluntarily, as a defense

witness at the selective prosecution hearing. She testified that

she had assisted her father, who was illiterate and whose

business affairs she handled, with his absentee ballot in 1994 by

signing for him. She also testified that she had told FBI agents

who had interviewed her that she had signed her father’s ballot

with his consent. See SP Tr. 296-303.

At the end o f its cross-examination, the government

abruptly demanded that Hutton provide handwriting exemplars

in open court. SPTr. 327. The clear import of this demand was

to threaten Hutton with prosecution for peijury for sticking to

her story. Certainly, the magistrate judge understood that to be

the message, since he interrupted the hearing to appoint counsel

for her. SPT r. 333.

In light o f the government’s threat to open a peijury

investigation and her newly appointed attorney’s sense that she

had not intelligently waived her Fifth Amendment rights, the

magistrate judge announced that “I ’m not going to make her get

on the stand now.” The U.S. Attorney responded:

Judge, we certainly understand that. And basically the last

thing, I think, that we had was the handwriting, w asn’t it[,]

Pat [Assistant U.S. Attorney Meadows]?

MR. MEADOWS: The handwriting. And I wanted to mark

those affidavits so that they could be identified that those

8

are the affidavits that we were talking about, and the

application. I haven’t had a chance to do that yet.

SP Tr. 345-46 (emphasis added). The magistrate judge refused

to require Hutton to testify as to the ballot affidavit:

I’m not going to make her do that. It seems to me that that

goes more to helping establish the perjury charge, because

ultimately what that would be is that would be the basis for

saying, this is the affidavit you claim to have signed for your

father. Here the handwriting on this affidavit does not

match your actual handwriting exemplars, therefore it must

be a perjury.

SP Tr. 349. He did, however, order Hutton to provide

handwriting exemplars. Later, the government’s own expert

witness concluded not that Tyree signed Powell’s ballot, but that

“the Sam Powell voter signature on the affidavit, compared to

the known handwriting o f Burnette Hutton writing the name Sam

Powell, again is very good agreement.” Tr. 737.

At trial, Sam Powell testified in a somewhat confused

fashion. He was unsure o f the year in which he was bom, and

his age. He testified that he did not remember giving Hutton

permission to fill out his ballot, but he also testified that his

daughter had never done anything for him in handling his affairs

that he had not told her to do. Tr. 438, 448.

Tyree then called Hutton as a defense witness. The

government immediately represented that it had an “open” case

file in its office regarding Hutton’s peijury. Since it could hardly

now claim that she had lied about whether she had signed her

father’s affidavit — its own expert witness had concluded that

this part o f her testimony was likely truthful — it now

represented that it was considering a peijury prosecution on the

question whether Hutton had indeed told the Assistant U.S.

Attorney this true fact when she was interviewed. Tr. 854-55,

962. In light o f this threat, Hutton, now provided with a second

9

court-appointed lawyer, quite sensibly declined to testify. Tr.

978.4

Since Hutton was thus made unavailable, petitioners sought

to introduce her testimony from the selective prosecution hearing

under Fed. R. Evid. 804(b)(1). They wished to introduce solely

that part of her testimony in which she said she had signed

Powell’s affidavit with his consent. The government objected

on the grounds that it had not had a full opportunity to cross-

examine her. Tr. 975. The district court agreed and excluded

Hutton’s entire testimony. Tr. 1052-56.

Finally, in addition to the testimony regarding the seven

ballots for which petitioners were indicted, the government

introduced, over petitioners’ strong and repeated objection,

testimony related to nearly one hundred other ballots that Tyree

had witnessed, although the prosecutor acknowledged that “I

honestly can’t prove anything illegally about these,” and that “I

can’t prove that they’re improper.” Tr. 206, 207.

Following the close o f evidence, the district court instructed

the jury that in order to convict the petitioners it had to find,

beyond a reasonable doubt, that they had “knowingly and

willfully signed” a particular application or affidavit “without

the knowledge and consent o f that voter.” But it almost

immediately undermined that statement with an instruction

regarding so-called “proxy voting” under state law:

[Tjhere is no such thing in Alabama as proxy absentee

voting.. . .

Further, only the absentee voter himself, or herself,

should sign the affidavit on the back side o f the return-mail

or affidavit envelope, addressed to the absentee election

manager.

4Despite the government’s representation, Hutton was never

prosecuted for any perjury.

10

Tr. 1289. After deliberating, the jury returned a verdict

convicting petitioner Smith on all seven counts with which he

had been charged and petitioner Tyree on all eleven counts with

which she had been charged.

D. Petitioners ’ Sentencing

Over petitioners’ objection that the court had initially

advised them prior to trial that the Base Level for their offenses

would be 6, Sent. Tr. 3-6, the court concluded that the appropri

ate Base Level was 12. See U.S. Sentencing Commission,

Guidelines Manual § 2H2.1(a)(2) (1997). The court enhanced

that Base Level by 6 additional levels for each petitioner,

yielding an Offense Level of 18. The court then sentenced each

petitioner to 33 months of imprisonment (the maximum

permissible under the Guideline Imprisonment Range), two

years o f supervised release, forty hours o f community service,

and the required $50.00 per count assessment fee.

E. The Court o f Appeals ’ Opinion

The Court of Appeals affirmed petitioner Smith’s

conviction on all counts, and affirmed petitioner Tyree’s

conviction on ten of the eleven counts with which she had been

charged. (It reversed her conviction on Count 12 — involving

the absentee ballot application o f Shelton Braggs — for

insufficient evidence.)

This Petition involves the Court o f Appeals’ rulings on five

issues: the selective prosecution claim; the need to prove lack

o f voter consent as an element o f the offenses charged; the

exclusion o f Burnette Hutton’s testimony; the calculation o f the

base offense level under the Sentencing Guidelines; and the

admission o f evidence about other ballots witnessed by Tyree.

1. Selective Prosecution. On the question o f selective

prosecution, the Court o f Appeals interpreted this Court’s

decision in United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456 (1996), to

require petitioners to establish the two components o f a

11

selective prosecution claim — discriminatory effect and

discriminatory motive — by “clear and convincing evidence,”

App. 11, rather than by a preponderance o f the evidence.

With respect to the question o f discriminatory effect, the

Court o f Appeals acknowledged that “the mere possibility o f

future prosecutions, without more, is not a sufficient basis upon

which to find that the requisite discriminatory effect or

selectivity showing has not been clearly proven,” App. 12, thus

holding that the Magistrate Judge had applied the wrong legal

standard in discounting the evidence he had found of similarly

situated but unprosecuted individuals. But rather than remand

for application o f the correct legal standard, the Court o f

Appeals decided to conduct its own survey o f the evidence —

which necessarily omitted any judgments o f witness credibility

— and concluded that petitioners had failed to show the

existence o f similarly situated individuals or an improper

motive. See App. 20-21 n.12.

The Court o f Appeals announced a stringent standard for

identifying “similarly situated” individuals for purposes o f a

selective prosecution claim:

[W]e define a “similarly situated” person . . . as one who

engaged in the same type o f conduct, which means that the

comparator committed the same basic crime in

substantially the same manner as the defendant — so that

any prosecution o f that individual would have the same

deterrence value and would be related in the same way to

the Government’s enforcement priorities and enforcement

plan — and against whom the evidence was as strong or

stronger than that against the defendant.

App. 15-16. In light o f this newly derived standard, the Court

o f Appeals held that petitioners had to identify

other individuals who voted twice or more in a federal

election by applying for and casting fraudulent absentee

12

ballots, and who forged the voter's signature or knowingly

gave false information on a ballot affidavit or application,

and that the voter whose signature those individuals signed

denied voting, and against whom the government had

evidence that was as strong as the evidence it had against

Smith and Tyree.

App. 16 (emphasis in original). The Court o f Appeals

acknowledged that the record from the selective prosecution

hearing included a dozen examples where an individual other

than one o f the petitioners witnessed ballots “in the name of [a]

voter who stated” to the FBI during its investigation “that he did

not vote.” App. 18-19. Nonetheless, the Court of Appeals

concluded that although “[tjhose individuals may have

committed the same type o f crimes as the defendants,. . . they

are not similarly situated with respect to the number of crimes

they committed,” because, while some o f them had fraudulently

witnessed two ballots, Tyree had witnessed six and Smith had

witnessed three. See id.

The Court o f Appeals also rejected both the direct and

circumstantial evidence o f racial bias presented by petitioners

with respect to the government’s discriminatory motive.

The direct evidence concerned the prosecutor’s Batson

violation, see supra page 6. The circumstantial evidence

concerned the involvement of the Alabama Attorney General in

the federal prosecution. State prosecutors pursued state-court

prosecutions against black defendants in those counties where

the circuit court judges and local district attorneys were white,

but federal charges in Greene County, where both the circuit

court judge and the local prosecutor were black. The

foreseeable, and arguably intended, consequence of this change

in forums on the racial composition o f the jury pool meant that

rather than presenting its case to a heavily black jury in a county

where the jurors were likely to be familiar with the nature o f

Greene County politics and high levels o f absentee voting, the

13

state’s pursuing a federal prosecution instead insured an

overwhelmingly white jury pool drawn from counties with very

different histories of absentee voting — juries whose members

were therefore likely to be unfamiliar with, and suspicious of,

customary Greene County politics.

The Court of Appeals rejected this evidence, concluding

that the allegation o f forum manipulation “rests . . . on an

assumption that black defendants will not be treated in a just

manner in federal court, an assumption which we reject.” App.

22. With respect to the district court’s finding of a Batson

violation, the Court o f Appeals stated that “[t]he only thing the

[trial] court’s rejection o f the government’s strike reveals is that

the court did not agree with the government’s observations

[about the prospective juror],” App. 22. The Court o f Appeals

ignored the fact that the only legal basis for using such a

“disagreement” to overcome the government’s use o f its

peremptory challenge was a finding that the challenge had been

used in a racially discriminatory manner and reasoned that, in

any event, the government’s misuse o f its peremptory challenge

provided “no basis for concluding that the underlying

prosecution is motivated by bias.” Id.

2. Lack o f Voter Consent. Petitioners had argued that the

district court’s charge did not clearly require the jury to find

that ballots had been cast without a voter’s consent in order to

find a violations of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973i(c) or 1973i(e).

The Court of Appeals held, first, that lack of voter consent

was not a necessary element o f either offense. App. 23,30-31.

Thus, according to the court below, even if a voter expressly

told another person to sign his absentee ballot affidavit, it

would be a violation o f federal criminal law, because, as a

matter o f Alabama state law a ballot that a voter has directed

another individual to fill out on his behalf is not valid. See

App. 25 (upholding Tyree’s conviction for signing Braggs’

14

ballot regardless o f whether the ballot was cast at his direction

“because she is not Braggs.”).

The Court o f Appeals acknowledged that Counts 1 and 2

o f the indictment — the conspiracy charge and the charge of

voting more than once in violation of § 1973i(e) — had alleged

that defendants had cast the identified ballots without the

relevant voters’ “knowledge and consent,” but it held that even

if this required the jury to be instructed on the question, the

district court’s charge was adequate when viewed “in its

entirety.” App. 33.

3. Exclusion o f Hutton testimony. The Court o f Appeals

rejected petitioner Tyree’s claim that the government’s threats

to prosecute Burnette Hutton for perjury at both the selective

prosecution hearing and the trial had deprived her o f her

constitutional right to present witnesses in her defense. The

Court did not comment at all on the government’s behavior, but

simply affirmed the district court’s exclusion of Hutton’s

testimony on the basis that the government “had not had a full

opportunity to cross-examine Hutton.” App. 30.

4. Calculation o f the Base Offense Level Under the

Sentencing Guidelines. The Court of Appeals affirmed the

district court’s selection o f a Base Offense Level o f 12, rather

than 6. The relevant sentencing guideline, Section 2H2.1 (a)(2)-

(3), provides for a base offense level of:

(2) 12, i f the obstruction occurred by forgery, fraud, theft,

bribery, deceit, or other means, except as provided in (3)

below; or

(3) 6, if the defendant (A) solicited, demanded, accepted,

or agreed to accept anything of value to vote, refrain from

voting, vote for or against a particular candidate, or register

to vote, (B) gave false information to establish eligibility

to vote, or (C) voted more than once in a federal election.

15

Although the language of § 2H2.1(3)(B) and (C) tracked

exactly the language of the statutes under which petitioners

were convicted, the Court of Appeals held, without citation to

any authority, that “ [t]he language o f (a)(2) applies in a case

where forgery, fraud, theft, bribery, deceit, or other means are

used to effect the vote of another person, or the vote another

person was entitled to cast.” App. 34. It restricted the language

o f (a)(3) to cases involving an individual who “acts unlawfully

only with respect to his own vote.” Id.

5. Admission o f evidence about Tyree’s witnessing other

ballots. Notwithstanding the prosecutor’s frank admission that

“I can’t prove anything illegalf] about these,” the Court o f

Appeals approved the admission of testimony about 95

additional ballot affidavits witnessed by petitioner Tyree as

“relevant to the conspiracy charge.” App. 28.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to Clarify the

Standards to be Applied to Claims of Selective

Prosecution and to Resolve a Conflict With Both this

Court’s Decisions and Those of Other Circuits

In United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456 (1996), this

Court squarely held that “[t]he requirements for a selective-

prosecution claim draw on ‘ordinary equal protection

standards.’” Id. at 465 (quoting Wayte v. United States, 470

U.S. 598, 608 (1985)). And it further insisted that “ [t]he

similarly situated requirement does not make a selective

prosecution claim impossible to prove.” Id. at 466. The Court

of Appeals’ decision in this case flouts both those principles

and conflicts with the approaches taken by other Courts o f

Appeals.

16

A. The Eleventh Circuit’s Imposition of the “Clear

and Convincing Evidence” Standard Conflicts with

this Court’s Decisions and the Decisions of Other

Courts of Appeals

The Court of Appeals drew from this Court’s statement in

Armstrong that, “in order to dispel the presumption that a

prosecutor has not violated equal protection, a criminal

defendant must present clear evidence to the contrary,” id. at

465, the conclusion that defendants in selective prosecution

cases must prove discriminatory purpose and effect not merely

by a preponderance of the evidence but by the higher standard

of clear and convincing evidence:

Clear evidence sounds like more than just a preponderance,

and evidence that is clear will be convincing. So, we

interpret Armstrong as requiring the defendant to produce

“clear” evidence or “clear and convincing” evidence which

is the same thing.

App. 11. Not only does this reasoning ignore the fact that the

standard of proof for establishing a selective prosecution claim

was not at issue in Armstrong, but it conflates a word used by

this Court in a very different context5 with well-established

5In Armstrong, this Court wrote that “‘the presumption of

regularity supports’ . . . prosecutorial decisions and, ‘in the

absence of clear evidence to the contrary, courts presume that

[prosecutors] have properly discharged their official duties,” ’

517 U.S. at 464, quoting from Chemical Foundation, Inc. v.

United States, 272 U.S. 1, 14-15 (1926). But the Court did not

announce the burden of proof standard and, in fact, went on

explicitly to note that, notwithstanding the presumption of

regularity, “the decision whether to prosecute may not be based

on ‘an unjustifiable standard such as race, religion, or other

arbitrary classification,’ Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448, 456

(1962).” 517 U.S. at 464. In Chemical Foundation itself, the

17

legal terms o f art. As Justice Scalia’s opinion for the Court in

Allentown Mack Sales & Service v. N.L.R.B., 522 U.S. 359,376

(1998), decisively noted:

“Preponderance o f the evidence” and “clear and

convincing evidence” describe well known, contrasting

standards o f proof. To say . . . that a preponderance

standard demands “clear and convincing manifestations,

taken as a whole” is to convert that standard into a higher

one.

In fact, no other court has ever, in any context, required litigants

to prove an equal protection violation by clear and convincing

evidence, rather than by a preponderance. Wayte’s citation of

Personnel Adm ’r o f Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979);

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous. Dev. Corp., 429 U.S.

252 (1977); and Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), as

the “prior cases” that set out the “standards” to be followed, 470

U.S. at 608-09, makes clear that the normal preponderance of

the evidence standard, applied in those cases, should apply to

claims o f selective prosecution as well.

The Eleventh Circuit’s ruling here clearly conflicts with the

approach taken by the Ninth Circuit in United States v.

Redondo-Lemos, 955 F.2d 1296 (9th Cir. 1992), appeal after

issue was whether actions taken by a State Department official to

whom the President had delegated statutory authority were

proper. The Court there discussed the presumption of regularity

only after concluding that there was no reason to overturn the

factual determination of the lower courts that the evidence failed

to establish misrepresentations or fraud. 272 U.S. at 14. Despite

its reference to the need for “clear evidence” to overcome the

presumption of regularity, however, the Court did not address the

burden of proof because the Circuit Court of Appeals had found

“no evidence” at all to support the claim. United States v.

Chemical Foundation, Inc., 5 F.2d 191,213 (3d Cir. 1925).

18

remand sub nom. United States v. Alcaraz-Peralta, 27 F.3d 439

(9th Cir. 1994). There, the Ninth Circuit stated that “[i]f the

district court finds by a preponderance o f the evidence that the

prosecutor's charging or plea bargaining practice has a

discriminatory impact, it must next determine whether the

prosecutor was motivated by a discriminatory purpose in

charging the defendant who is before the court,” 955 F.2d at

1302 (emphasis added) and concluded that if, “after giving the

government ample opportunity to present its side o f the case,

the district court finds by a preponderance o f the evidence that

there has been intentional discrimination on the basis o f a

suspect classification, it may then fashion a remedy to address

the constitutional violation.” Id. (emphasis added).

The Eleventh Circuit’s approach in this case also conflicts

with the general use o f the preponderance of the evidence

standard in cases involving equal protection claims against

prosecutors or other law enforcement officials decided by the

Second, Fourth, and Eighth Circuits. See, e.g., United States v.

Darden, 70 F.3d 1507, 1531 (8th Cir. 1995) (in ruling on a

Batson challenge, the trial court “must decide ‘whether the

party whose conduct is being challenged has demonstrated by

a preponderance o f the evidence that the strike would have

nevertheless been exercised even if an improper factor had not

motivated in part the decision to strike’”), cert, denied, 517

U.S. 1149 (1996), quoting Jones v. Plaster, 57 F.3d 417, 421

(4th Cir. 1995); Eagleston v. Guido, 41 F.3d 865, 870 (2d Cir.

1994) (trial court applied a preponderance o f the evidence

standard to equal protection claim alleging sex discrimination

in police department’s enforcement o f policy regarding

domestic violence), cert, denied, 516 U.S. 808 (1995).

B. The Standard Adopted Below for Identifying

“Sim ilarly S ituated” Individuals When

Adjudicating a Selective Prosecution Claim

Departs Dramatically from Prior Caselaw and

Forecloses the Claim as a Practical Matter

19

In its decisions articulating the elements o f a selective-

prosecution claim, this Court has repeatedly held that

defendants must show that there were “similarly situated”

individuals who were not prosecuted. See, e.g., Armstrong, 517

U.S. at 465; Wayte, 470 U.S. at 605. The phrase is “similarly

situated,” not “identically situated in every respect,” as this

Court’s decisions show.

Armstrong discussed this Court’s unanimous decision in

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985), to illustrate the

operation o f the “similarly situated” requirement:

In Hunter, we invalidated a state law disenfranchising

persons convicted o f crimes involving moral turpitude.

Our holding was consistent with ordinary equal protection

principles, including the similarly situated requirement.

There was . . . indisputable evidence that the state law had

a discriminatory effect on blacks as compared to similarly

situated whites: Blacks were by even the most modest

estimates at least 1.7 times as likely as whites to suffer

disfranchisement under the law in question . . . .

Armstrong, 517 U.S. at 466-67. O f course, blacks and whites

were not identically situated in any respect except that they

were citizens o f Alabama subject to the disenfranchisement

provision at issue in Hunter. Like the plaintiffs in Hunter —

Victor Underwood (who was white) and Carmen Edwards (who

was black) — everyone, black or white, who was convicted of

one o f the listed crimes was disenfranchised. The probability

o f disenfranchisement for both blacks and whites in this group

was thus the same. The statistics cited by this Court were based

upon the group of all citizens. But since this group includes

both those who may have committed the specified offenses and

those who did not, Hunter and Armstrong demonstrate that

“similarly situated” cannot be synonymous with “identical.”

“Similar” means “comparable” in relevant ways.

20

In this case, however, the Eleventh Circuit invented a

“similarly situated’' requirement that, contrary to this Court’s

insistence that the requirement “does not make a selective

prosecution claim impossible to prove,” Armstrong, 517 U.S.

at 466, does precisely that. It requires not only that a defendant

identify other individuals who “committed the same basic crime

in substantially the same manner as the defendant,” but that a

defendant show that prosecution of these other individuals

“would have the same deterrence value and would be related in

the same way to the Government's enforcement priorities and

enforcement plan” and that the evidence against these

individuals “was as strong or stronger than that against the

defendant.” App. 16.

There is simply no way that any defendant could prove

what the Eleventh Circuit demands. Even once a defendant

obtains discovery — a substantial hurdle that the petitioners in

this case overcame — it is unclear how he can ever establish the

relative deterrence values of different prosecutions, the actual

scope of the Government’s enforcement priorities or, without

the ability to conduct a complete criminal investigation and trial

itself, the relative strength of various cases before hypothetical

juries.

The utter impossibility of the Eleventh Circuit’s new

standard is powerfully demonstrated by its application in this

case. Petitioner Smith was convicted o f illegalities with regard

to three voters’ absentee ballots. Petitioner Tyree was

convicted o f illegalities with regard to six voters’ ballots. And

yet, the Eleventh Circuit held that they were not similarly

situated with respect to other individuals who had arguably

committed precisely the same offense with respect to two

ballots. See App. 18-19. Under such a standard, there will

virtually never be “similarly situated” individuals.

Discussions o f the “similarly situated” requirement by

other Courts o f Appeals take a markedly different tack. The

21

D.C. Circuit, for example, viewed the test as whether “others

similarly situated have not generally been proceeded against

because o f conduct o f the type forming the basis of the charge

against [the defendants.]” Attorney General v. Irish People,

Inc., 684 F.2d 928 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (emphasis added) (quoting

Attorney Gen. v. INAC, 530 F. Supp. 241,254 (S.D.N.Y. 1981),

a ffd66 8 F.2d 159 (2d Cir. 1982)), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1172

(1983). And the Eighth Circuit, in a prosecution for multiple

voting, rejected other kinds o f irregularities as not “sufficiently

similar” to the offenses with which defendants were charged,

but suggested that other acts of “absentee ballot forgery or

fraud” would have been. United States v. Parham, 16 F.3 d 844,

846 & n.3 (8th Cir. 1993).

II. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to Resolve a

Conflict Among the Circuits Over the Construction of

Two Criminal Provisions of the Voting Rights Act

The substantive offenses with which petitioners were

charged are defined by 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c) and 42 U.S.C. §

1973i(e). Section 1973i(c) provides, in pertinent part, that

“ [w]hoever knowingly or willfully gives false information as to

his name, address, or period o f residence in the voting district

for the purpose o f establishing his eligibility to register or vote,

or conspires with another individual for the purpose of

encouraging his false registration to vote or illegal voting” shall

be guilty o f a federal crime. In this case, one or both o f the

petitioners were alleged to have submitted absentee ballot

applications and absentee ballots in the names of seven voters.

A plain reading o f the statutory language suggests that a person

who facilitates the casting o f an absentee ballot at the request of

another does not give false information. But, according to the

Eleventh Circuit, “nothing in § 1973i(c) requires that the

information be given without the voter's permission.” App. 23.

Thus, according to the Eleventh Circuit, even if a qualified

voter expressly requests that another person file an absentee

22

ballot request for him, complying with that request constitutes

a federal crime.

Similarly, the Eleventh Circuit held in this case that section

1973i(e), which makes it a crime to “vot[e] more than once” in

a federal election, is violated if an individual fills out and signs

another individual’s absentee ballot even if the qualified voter

affirmatively consented to that being done: “What we have

already held about [lack o f a voter’s consent] not being a

necessary element o f the § 1973i(c) offense applies as well to

the § 1973i(e) offense.” App. 30-31.

The approach taken below squarely conflicts with the view

taken by the other Courts o f Appeals to have reached this

question. In every other reported case involving prosecutions

under § 1973i(c) or (e) for absentee ballot irregularities,6 courts

have assumed that the government must show that applications

were filed or votes were cast without the consent o f the nominal

voter. See, e.g., United States v. Cole, 41 F.3d 303, 308 (7th

Cir. 1994) (affirming a conviction on the ground that “the

absentee voters were not expressing their wills or preferences”),

cert, denied, 516 U.S. 826 (1995); United States v. Boards, 10

F.3d 587, 590 (8th Cir. 1993) (finding “ample evidence from

which a reasonable jury could find Boards . . . marked the

voter’s absentee ballot without authorization in violation o f 42

U.S.C. § 1973i(c)”), cert, denied, 512 U.S. 1205 (1994). In

fact, the Sixth Circuit held that section 1973i(e) would be

unconstitutionally vague if it were applied to conduct that did

not involve the lack o f a nominal voter’s consent. See United

States v. Salisbury, 983 F.2d 1369, 1379 (6th Cir. 1993). Prior

prosecutions in the Eleventh Circuit assumed precisely the same

6 The exception involves prosecutions under a different part of

§ 1973i(c) — the part that makes it a crime to pay or offer to pay a

voter for his or her vote. Lack of consent to be paid is obviously

irrelevant to a crime complete as of the time an offer to pay is made.

23

lack-of-consent requirement. See, e.g., United States v.

Gordon, 817 F.2d at 1542; United States v. Hogue, 812 F.2d

1568, 1573-74(11th Cir. 1987).

The construction adopted below is not merely in conflict

with the pre-existing caselaw: it is a wrongheaded interpretation

o f Congressional intent. Consider, for example, the thousands

o f absentee ballot applications in the 2000 Florida presidential

election on which Republican Party representatives inserted

voter identification numbers that had inadvertently been left off

preprinted forms. Even though these partisan workers were not

among the categories o f persons authorized under Florida law

to submit absentee ballot requests, see Fla. Stat. Ann. §

101.62(l)(b), the Florida Supreme Court held that these

applications were valid since there was no “fraud, gross

negligence, or intentional wrongdoing.” Jacobs v. Seminole

County Canvassing Board, No. SC00-2447, 2000 Fla. LEXIS

2404, at *11 (Fla. Dec. 12, 2000). But under the Eleventh

Circuit’s interpretation in this case, the actions were violations

o f §§ 1973i(c) or 1973i(e). No one seriously expects United

States Attorneys in Florida to bring prosecutions under these

sections against the officials and party workers who filled in

additional information on ballot applications that reflected the

will and consent of qualified voters. The reason is obvious:

Congress never meant to criminalize such conduct, and neither

statute should be read to reach such a result.

In this case, the jury’s verdict is entirely consistent with its

having believed either that the voters involved consented to

petitioners’ involvement in their absentee ballot applications

and absentee ballots or that petitioners believed in good faith

that they had that consent. Indeed, only such a belief could

support the ju ry’s convicting petitioner Tyree on Counts 12 and

13 o f the indictment, involving the application and ballot of

Shelton Braggs since, as the Eleventh Circuit itself

acknowledged, there was absolutely no evidence in the record

o f lack of consent.

24

This Court should grant certiorari both to resolve the

conflict among the circuits and to prevent 42 U.S.C. § 1973i

from becoming an “assimilative crimes” provision, see 18

U.S.C. § 13, under which individuals may be federally

prosecuted for violating technical provisions o f state election

law to carry out a voter’s wishes.

III. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to Address the

Proper Application of the Sentencing Guidelines to

the Offenses with which Petitioners were Charged

Appendix A to the Sentencing Guidelines makes § 2H2.1

applicable to a range o f voting-related offenses, including 42

U.S.C. §§ 1973i(c) and 1973i(e), under the general heading of

“Obstructing an Election or Registration.” App. 63. That

section of the Guidelines establishes three significantly different

base offense levels:

(1) 18, if the obstruction occurred by use o f force or threat

o f force against person(s) or property; or

(2) 12, if the obstruction occurred by forgery, fraud, theft,

bribery, deceit, or other means, except as provided in (3)

below, or

(3) 6, if the defendant (A) solicited, demanded, accepted,

or agreed to accept anything of value to vote, refrain from

voting, vote for or against a particular candidate, or register

to vote, (B) gave false information to establish eligibility

to vote, or (C) voted more than once in a federal election.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual § 2H2.1

(1997) (emphasis added). The courts below acted as if §

2H2.1(a)(3) simply did not exist, and completely ignored the

exceptions clause o f § 2H2.1(a)(2).

The substantive offenses of which petitioners were

convicted were (1) providing false information to establish

eligibility to vote, 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c) (Counts 3-13), and (2)

25

voting more than once in a federal election, 42 U.S.C. §

1973i(e) (Count 2). The conspiracy in which they were alleged

to have been engaged was a conspiracy to commit those two

substantive offenses. Clauses (3)(B) and (C) quoted above,

providing for a base offense level o f 6, track exactly the

language of the statutory provisions under which petitioners

were convicted. Thus, the applicable Sentencing Guideline

clearly provides that the particular forms o f fraud or deceit of

which petitioners were convicted warrant a base level of 6, even

though other forms o f forgery, fraud, or deceit may carry a

higher Base Offense Level. See, e.g., Anderson v. United

States, 417 U.S. 211,214-15 (1974) (casting fictitious votes on

voting machines and then destroying poll slips to conceal the

fraud); United States v. Bowman, 636 F.2d 1003, 1006-07 (5th

Cir. 1981) (paying voters to vote for particular candidates).

The Court o f Appeals simply ignored the identity between

the statutory language o f the offense for which petitioners were

convicted and the language o f § 2H2.1(a)(3)(B) and (C).

Instead, without citation to any authority, it fashioned a

distinction not reflected in the words o f the Guidelines:

The language o f (a)(2) applies in a case where forgery,

fraud, theft, bribery, deceit, or other means are used to

effect the vote o f another person, or the vote another

person was entitled to cast. By contrast, the language o f

(a)(3) addresses an individual who acts unlawfully only

with respect to his own vote—an individual who accepts

payment to vote, gives false information to establish his

own eligibility to vote, or votes more than once in his own

name. The offenses for which Smith and Tyree were

convicted involved the votes o f other individuals . . . .

App. 34.

In Chapman v. United States, 500 U.S. 453, 457 (1991),

this Court noted that the applicable Sentencing Guideline

provision “parallel[ed] the statutory language.” See also id. at

26

470 n.6 (Stevens & Marshall, JJ., dissenting). This Court

should grant certiorari to make clear that when a sentencing

court is faced with different base offense levels, and the

Sentencing Commission has distinguished among statutory

offenses by using their language in establishing base offense

levels, the sentencing court is bound to apply the base offense

level identified by the Sentencing Commission.

IV. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to Restore the

Protections of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to

Petitioner Tyree

Petitioner Tyree has a constitutional right, under the

compulsory process clause o f the Sixth Amendment and the due

process clause o f the Fifth Amendment to “present [her] own

witnesses to establish a defense.” Washington v. Texas, 388

U.S. 14, 19 (1967). “ [Substantial government interference

^ ith a defense witness’s free and unhampered choice to testify

violates due process” rights o f the defendant. United States v.

Hammond, 598 F.2d 1008, 1012 (5th Cir. 1979). In Webb v.

Texas, 409 U.S. 95,98 (1972), this Court held unanimously that

when threats of prosecution for peijury “effectively drove [a

critical] witness off the stand,” the defendant was deprived of

“due process of law under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

In this case, the government substantially interfered with

Tyree’s ability to present the testimony o f Burnette Hutton.

Hutton was prepared to testify that she had signed her father’s

absentee ballot affidavit (he was illiterate) with his consent.

That testimony, if believed, might have led the jury to acquit

Tyree on Count 7, which involved her allegedly having signed

Powell’s absentee ballot application. Presented with this

possibility by her testimony at the selective prosecution hearing,

the government reacted by both trying to intimidate Hutton on

the stand — through the extraordinary stratagem of demanding

that she provide handwriting exemplars in public and without

notice — and threatening to indict her for peijury. In the end,

27

the government did not indict her for perjury; indeed,

handwriting exemplars later obtained disproved the

government’s hypothesis that she had lied about signing the

ballot affidavit. Nevertheless, the government prevented

H utton’s sworn pre-trial testimony from being presented to the

jury on the ground that its cross-examination had been

curtailed, albeit by its own conduct.

Given the government’s threats at the selective prosecution

hearing, Hutton was virtually compelled to invoke her Fifth

Amendment rights and terminate her testimony. Thus, Tyree

was deprived o f a potentially critical witness on the question of

Sam Powell’s consent. The federal courts routinely refuse to

allow criminal defendants to prevent the introduction of prior

testimony pursuant to Fed. R. Evid. 804(b)(1) on the ground

that did not have the opportunity for cross-examination where

the witness’ s unavailability for cross-examination resulted from

intimidation by the defendant. See, e.g., Magouirk v. Warden,

No. 99-30594 (5th Cir. Jan. 15, 2001) and cases cited.

Consistent with Webb, the same rule should apply to the

government. Accordingly, this Court should grant certiorari to

reaffirm the rule ignored by the Eleventh Circuit: when the

government intimidates a defense witness, driving that witness

from the stand and preventing the jury from hearing testimony

that the government’s own expert acknowledges to be truthful,

it violates a defendant’s rights under the Sixth Amendment and

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

V. The Court Should Grant Review to Resolve the

Conflict Between the Decision Below and Rulings

of other Circuits that Inherently Prejudicial

Evidence of Similar Acts by a Criminal Defendant

May Be Admitted Only if the Acts are Shown to be

Unlawful

Petitioners were charged with crimes relating to the casting

o f seven voters’ absentee ballots. Nevertheless, over their

28

strong objection on grounds of both relevance and prejudice,

the prosecution introduced evidence regarding at least 95 other

absentee ballots witnessed by Connie Tyree. The prosecutor

conceded that the government could not prove “anything”

illegal, or even “improper” about these ballots.7 The inherently

prejudicial danger of this evidence — the suggestion that

anyone who witnessed as many ballots as Tyree did must have

been doing something wrong — is obvious. But the Court of

Appeals held the evidence was relevant to the conspiracy count

o f the indictment, even though the conduct was legal.

This holding conflicts with the decisions o f other Circuits

requiring that evidence that purports to show that defendants

have committed similar acts may be admitted only if the jury is

provided with a basis for concluding that the other acts were

unlawful and were similar to those charged along the relevant

dimension.

Thus, in United States v. Guerrero, 650 F.2d 728 (5th Cir.

1981), the court reversed the conviction o f a doctor who had

been charged with dispensing controlled medications outside

the usual course of professional medical practice because he

had been prejudiced by the introduction o f evidence regarding

other prescriptions as to which no illegality or impropriety was

shown. “The common characteristic” rendering such evidence

relevant and admissible, the Fifth Circuit held, “must be the

significant one for the purpose o f the inquiry at hand.” Id. at

733 (internal citations omitted). Sales that were not

Indeed, encouraging and assisting absentee voting is a

constitutionally protected activity. See, e.g., Smith v. Meese, 821

F.2d 1484 (11th Cir. 1987). The Magistrate Judge found, as a

matter of fact, that absentee voting in Greene County was critical

to black citizens' ability to participate in the electoral process.

App. 41.

29

intentionally outside the usual practice were not “in any way

relevant” to the question o f the intent behind the charged sale.

Id at 734.

Guerrero was followed in United States v. Anderson, 933

F.2d 1261 (5th Cir. 1991), where the Court o f Appeals directed

the trial court to determine whether the evidence o f other fires

was sufficient to permit the jury to conclude, by a

preponderance, that they were arson incidents in which the

defendant was involved. The same principles have been given

application by other panels o f the Eleventh Circuit. See, e.g.,

United States v. Veltmann, 6 F.3d 1483, 1499 (11th Cir. 1993)

(“For extrinsic offenses to be relevant to an issue other than

character, they must be shown to be offenses, and must also be

similar to the charged offense”) (emphasis in original); United

States v. Dothard, 666 F.2d 498, 501-05 (11th Cir. 1982). See

also United States v. Sullivan, 919 F.2d 1403, 1416-17 (10th

Cir. 1990) (general assertion by prosecutor that evidence was

relevant because it was part o f history o f conspiracy was

insufficient justification for its admission).

In this case, the courts below neither determined that the

jury could have found that Tyree improperly witnessed the other

ballots — a finding it could hardly have made in light o f the

prosecutor’s concession — nor weighed the probative value of

the evidence against the risk o f prejudice. Here that risk was

realized. This Court should grant the writ to resolve the

conflict between the decision below and those cited in the

preceding paragraph.

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ o f certiorari should be granted.

30

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

(counsel o f record)

Jacqueline Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 965-2200

Collins Pettaway, Jr.

Chestnut, Sanders, Sanders

& Pettaway

1405 Jeff Davis Avenue

Selma, Alabama 36702

(334) 875-9264

Pamela S. Karl an

559 Nathan Abbott Way

Stanford, California 94305

(650) 725-4851

APPENDIX

App. 1

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

(October 25,2000)

Before CARNES, BARKETT and MARCUS, Circuit Judges.

CARNES, Circuit Judge:

This appeal arises out o f the convictions o f Frank Smith

and Connie Tyree on a number o f federal criminal counts

relating to violation o f absentee voter laws in connection with

the November 1994 general election in Greene County,

Alabama. The two of them raise numerous issues on appeal,

contending that: (1) the indictment should have been dismissed

on the ground o f selective prosecution based on race and

political affiliation; (2) there was insufficient evidence to

convict Tyree on two of the counts o f giving false information

in violation o f 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c); (3) the United States

Sentencing Guidelines were misapplied in sentencing Smith

and Tyree; (4) they were convicted on multiplicitous counts; (5)

certain evidence relating to absentee ballot affidavits witnessed

by Tyree should not have been admitted into evidence; (6) the

jury was erroneously instructed regarding Alabama law and

"proxy" voting; and (7) Tyree was denied her constitutional

right under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to present

witnesses in her defense.

For the reasons set forth below, we conclude that all o f

Smith's arguments miss the mark, and his convictions and

sentence are due to be affirmed in all respects. All but one o f

Tyree's arguments miss. Her conviction is due to be affirmed

except on Count 12; reversal o f that part o f her conviction

makes it necessary that she be re-sentenced.

App. 2

I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY

In January o f 1997, Frank Smith and Connie Tyree were

charged in a thirteen-count indictment with offenses arising out

o f the November 8, 1994 general election in Greene County,

Alabama. Among the offices to be filled in that election was the

office o f Member o f the United States House o f

Representatives, a fact which supplies a necessary element o f

the federal charges. Count 1 o f the indictment charged Smith

and Tyree with conspiring, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 371, to

vote more than once in a general election by applying for and

casting fraudulent absentee ballots in the names o f voters

without the voters' knowledge and consent, in violation o f 42

U.S.C. § 1973i(e), and with conspiring to knowingly and

willfully give false information as to a voter's name and address