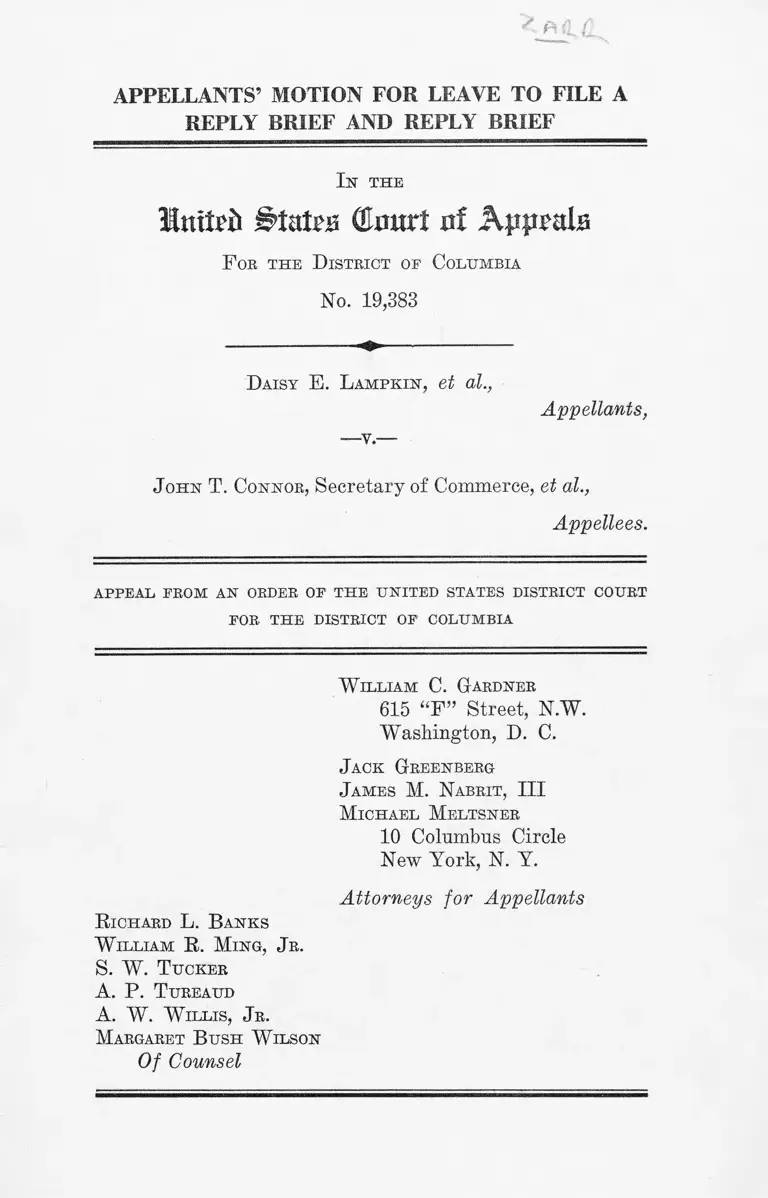

Lampkin v. Connor Appellants' Motion for Leave to File a Reply Brief and Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lampkin v. Connor Appellants' Motion for Leave to File a Reply Brief and Reply Brief, 1965. 87297348-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76a42ebd-fc2b-4f95-ac59-d11e21eeac1f/lampkin-v-connor-appellants-motion-for-leave-to-file-a-reply-brief-and-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

APPELLANTS’ MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A

REPLY BRIEF AND REPLY BRIEF

In the

MnxUb CUrntrl at kpprais

F ob the D istbict of Columbia

No. 19,383

Daisy E. L ampkin, et al.,

Appellants,

— v.—

J ohn T. Connob, Secretary of Commerce, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM AN ORDER OP THE UNITED STATES DISTBICT COURT

FOR- THE DISTBICT OP COLUMBIA

W illiam C. Gardner

615 “ F ” Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

R ichard L. B anks

W illiam R. Ming, Jr.

S. W . Tucker

A . P. T ureaud

A . W . W illis, J r .

Margaret B ush WVlson

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Reply Brief ........ .................. 1

Reply B r ie f.............. -............................... ....... ..................... 5

I. The Standing to Sue of Group I and Group II

Appellants Is Unaffected by the Passage of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ........................... 5

II. This Controversy Is Justiciable....................... . 11

III. Title V III of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Is

Not Pertinent to Decision of This Case ........... 18

Table oe Cases

American Comm, for Protection of Foreign Born v.

Subversive Activities Control Board, 380 U. S. 503 .... 11

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186.......................................12,13,14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ............... 16

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549 .............................. 14

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41 ................................... . 10

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U. S. 368 .......................................12,13

Rainwater v. United States, 356 U. S. 590 ................... 21

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 ...................................12,13

United States v. Muniz, 374 U. S. 150 ........................... 21

United States v. Wise, 370 U. S. 405 ............................... 21

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U. S. 1 ...........................12,13,14

n

PAGE

Table op

Constitutional and Statutory P rovisions

U. S. Const., Art. 1, §2, Cl. 1 ....................................... 16

Census and Apportionment Act of 1929 ............... 11,13, 20

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Title VIII, 78 Stat. 286 ....18,19, 20,

21, 22

2 U. 8. C. §2a ...................................................................... 17, 22

13 U. S. C. §141 ....................................... ,.......................... 17, 22

13 IT. S. C. §221.................................................................... 19

42 IT. S. C. §§1971 et seq....................... ............................. 19

Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Act of Aug. 6, 1965, 79

Stat. 437) ........................................................ 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Other A uthorities

Hearings before House Committee on the Judiciary

on H. R. 7152, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. ser. 4, part 4

(1963) ................................................................................ 19

Report of the President’s Committee on Registration

and Voting Participation (November 1963) ........... 11

IT. S. Code Congressional and Administrative News,

89th Cong., 1st Sess........................................................ .6, 20

Isr t h e

Hntteft States (Euart nf Appeals

F ob the D istbict of Columbia

No. 19,383

Daisy E. L ambkin, et al.,

Appellants,

J ohn T. Connob, Secretary of Commerce, et al.,

Appellees.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE REPLY BRIEF

Appellants move the Court for leave to file the attached

reply brief and as grounds for such relief state the fol

lowing :

1. This is an appeal from a March 29, 1965 order of the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

dismissing the complaint herein on the ground that ap

pellants do not have standing to sue. Notice of appeal to

this Court was filed April 18, 1965. Appellants’ brief was

filed here July 23, 1965. Appellees filed their brief on Sep

tember 3, 1965.

2. As a primary reason for affirming the order of the

District Court, appellees’ brief urged that the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, Public Law 89-110, 89th Cong. 1st Sess.

(August 6, 1965), enacted subsequent to the decision below

and the date appellants filed their brief, nullifies denial

and abridgment of the franchise to the extent that ap

2

pellants do not have standing to sue. Appellants dispute

this contention, but because its disposition involves issues

presently pending, or to be brought, before the United

States Supreme Court, appellants moved, on or about Sep

tember 15, 1965, for an order postponing oral argument

of this appeal pending decision by the United States Su

preme Court of the constitutional rights of citizens to vote

in state elections without payment of a poll tax. On or

about September 17, 1965, appellees filed a consent to the

relief sought by the motion to postpone oral argument.

However, appellees indicated disagreement with certain of

appellants’ contentions as to the effect of the outcome of

litigation pending before, or soon to be brought to, the

Supreme Court, and on October 27, 1965, this Court, per

Bazelon, Chief Judge, entered an order denying the motion

to postpone oral argument on the ground of absence of

consent to “ abide by the decision of the Supreme Court.”

3. Prior to the disposition of appellants’ motion to post

pone oral argument, time for filing a reply under the rules

of the Court expired. As appellees’ brief raised questions

not fully discussed in appellants’ brief (because they re

lated to the Voting Eights Act of 1965 which was enacted

subsequent to the filing of that brief) unless this motion

for leave to reply is granted, the court will not have an

opportunity to consider appellants’ views as to the issues

raised initially by appellees’ brief. In addition, appellees’

brief seeks affirmance on the basis of arguments raised be

fore, but not relied upon by, the District Court. Unless

this motion is granted, the court will not have an opportu

nity to consider appellants’ views as to these issues.

4. This case involves decision of delicate, complicated

and serious constitutional questions never before fully

3

presented to a United States Court. These questions touch

the right to vote and the value of the votes of millions of

Americans. Moreover, construction of a portion of the

Constitution is sought. The Court should consider such

matters on the basis of as full as possible a presentation

and exploration of pertinent facts and authorities. The

character of appellees’ brief is such that appellants re

spectfully submit the court will be assisted, and justice

served, by consideration of the attached reply brief.

5. The granting of this motion will in no manner cause

prejudice, inconvenience, or loss to appellees. It will per

mit the court to be guided by additional authorities wdien

considering the issues raised herein.

W herefore appellants pray that the motion for leave to

file a reply brief be granted and the reply brief attached

hereto be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam C. Gardner

615 “F ” Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

R ichard L. B anks

W illiam R. Ming, J r .

S. W. Tucker

A. P. T ureaud

A. W . W illis, J r .

Margaret B ush W ilson

Of Counsel

I n th e

M <xt2$ C m irt n l A p p e a ls

F or the D istrict of Columbia

No. 19,383

Daisy E. L ampkin, et al.,

Appellants,

J ohn T. Connor, Secretary of Commerce, et al.,

Appellees.

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

I.

The Standing to Sue of Group I and Group II Appel

lants Is Unaffected by the Passage of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965.

In their brief appellees urged that the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 (Act of August 6, 1965; 79 Stat. 437) nullifies

denial and abridgment of the franchise as alleged by Group

II appellants (Negro citizens of southern states) and,

therefore, these appellants are no longer injured by ap

pellees’ failure to enforce §2 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. It is urged that Group I appellants (voters from

northern and eastern states) only assert the right to re

dress dilution and the debasement of their votes to the ex

tent Group II appellants have been injured, and that they

are also without standing.

6

In considering the effect of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 on the standing of Group I and Group II appellants,

it must be noted that the Act itself does not remove all

barriers to the exercise of the franchise alleged by ap

pellants. Even if fully implemented and effective (ap

pellants will argue below that it has not been fully imple

mented and effective), it would only nullify certain denials

of the franchise, e.g., literacy tests and constitutional in

terpretation tests. The Act does not purport to nullify the

poll tax requirement of Mississippi and Virginia which

has denied and abridged the franchise of appellants Har

ris, Mason, Gillis, L. McGhee, W. McGhee, and Hancock.

Enough citizens are denied or abridged the franchise by

these poll tax requirements, as well as those of Alabama

and Texas, to insure that these states would lose represen

tatives (and states represented by Group I appellants gain

representatives) if §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment is en

forced. While the Attorney General has brought suit to

eliminate the poll tax prerequisite for voting in state elec

tions in these four states, the suits have not been decided

in the lower courts and it cannot be assumed that the At

torney General will be successful. Indeed, he testified be

fore the Congress that there was a substantial risk that a

congressional prohibition of state poll taxes would be de

clared unconstitutional. See, e.g., U. S. Code Congressional

and Administrative News, 89th Cong. 1st Sess., p. 2550.

Moreover, the Act, §10 (d) specifically provides the pro

cedure to be followed if the taxes are declared constitu

tional. That a voting barrier is now—after this suit was

filed and decided in the lower court—undergoing legal chal

lenge is in itself of no consequence in appraising appel

lants’ standing.

7

Appellees’ argument based on the Voting Rights Act,

therefore, fails because the Act does not account for all

denial and abridgment of the franchise asserted by appel

lants. Whatever the effect of the Act on actual patterns

of denial or abridgment of the franchise, it cannot be given

effect which would remove the standing of all Group I

appellants.1

With respect to state poll tax requirements, there is a

serious error in appellees’ brief. On page 23 it states:

“ Of course, the fourteen appellants from the northern

states gain no “ standing” [from state poll tax require

ments] . . . because voting for representatives to the United

States Congress is not at all affected thereby.” The lan

guage of §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment expressly states

that the basis of apportionment of Representatives shall be

reduced when the right to vote at any election “ for the choice

of electors for President and Vice-President of the United

States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and

Judicial officers of a state or the Members of the Legis

lature thereof is denied.” (Emphasis supplied.) Thus,

appellants clearly would gain Representatives in Congress

from a requirement of payment of a poll tax in state elec

tions, for such a requirement denies and abridges the

franchise within the meaning of §2 and would lead to a

reduction of the basis of apportionment of the poll tax

states.

But even if the Voting Rights Act did nullify state poll

taxes it could not deprive appellants of standing. Ap

pellees’ brief asks the Court to treat the Voting Rights

Act as if it had in fact removed all barriers to Negro

1 Of course, under appellees’ theory that Group I and Group II

appellants have an identity of interest, standing for Group I

appellants would mean standing for Group II appellants.

8

voting in the South, but elimination of pervasive racial

discrimination in southern voting prior to the next census

is not the certainty appellees would have the Court find.

While there has been a modest increase in registration in

a small number of counties, it has been estimated that

over three million Negroes in affected states remain unreg

istered. When compared to the total number of Negroes

whose franchise has been denied and is still denied by

intimidation, failure to permit registration, poll taxes,

failure to abide by the terms of the Voting Act and other

state requirements, the effect of the Act has been slight.

According to the New York Times, October 30, 1965, p. 1,

October 31, 1965, §4, p. 4, the increase has been less than

166,000, and despite the hundreds of southern counties with

documented histories of discriminatory voting practices,

only 32 federal registrars have been appointed.

To the extent the question of appellants’ standing turns

on the existence of denial and abridgment of the franchise,

appellees’ position is wishful thinking. It goes without

saying (and without referring to the well-known conditions

which prompted Congress to pass the Act) that the mere

passage of the Act, in and of itself, cannot be taken to

end denial of the franchise. Unsuccessful attempts to end

discrimination against Negro voting are as old as the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In the last analysis,

the effectiveness of the Voting Eights Act of 1965 is a

question of fact of the sort determined by district courts

on full records and not an appropriate matter for this

Court to determine as a matter of law. For this reason,

appellees’ whole standing argument is flawed. On the one

hand, they seek to keep appellants from a hearing on the

factual issues of the case, including allegations of disfran

chisement; on the other, they rely in this Court on the

9

actual effectiveness of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in

ending denial and abridgment of the franchise.

Even if the Act affected the standing of all Group II

appellants (which it does not), it would not thereby affect

the standing of Group I appellants. These appellants as

sert that the failure of appellees to administer duties to

apportion in a constitutional manner results in their con

gressmen representing more persons than congressmen

from states which deny or abridge the right to vote as

specified in §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment; and that

their state would receive at least one additional represen

tative in Congress if §2 is enforced, thereby resulting in

an increase in the value of each appellant’s vote. Because

much of the denial of the franchise which gives rise to

the injury claimed by Group II appellants takes place in

states affected by the provisions of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, appellees in their brief attempt to identify the

standing of Group II appellants with the standing of Group

I appellants, and they urge that if Group II appellants do

not have standing because of the Act, Group I appellants

do not have standing. As has been shown above, Group

II appellants have standing (even if one assumes the Vot

ing Rights Act has actually ended racially discriminatory

literacy tests and similar devices) because it does not sus

pend the operation of state poll taxes. But even if Group

II appellants were for some reason without standing, it

does not follow that there is no injury to Group I appel

lants: Group I appellants alleged facts establishing dis

crimination against Negroes in southern states in order

to show that they are injured by the failure of appellees

to enforce §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The instances

of denial of the franchise alleged in the complaint were

obviously chosen because at the time it was drafted they

10

were the most obvious demonstration of the injury suf

fered. But Group I appellants did not thereby suggest

that these were the only restrictions on the franchise which

gave rise to the injury for which they sought redress. The

complaint is broad enough to encompass all denials or

abridgment of the right to vote which work, if §2 is en

forced, to increase the representation of Group I appellants.

Cf. Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41.

Group I appellants cannot be restricted to those incidents

of denial of the franchise alleged in a complaint filed two

years prior to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of

1965. At the time the complaint was drafted, proposal of

the Act, much less its adoption, was unlikely. Unreason

able residence requirements, intimidation, refusal to proc

ess applications for registration or the processing of such

applications at an extremely slow rate, state poll taxes,

use of tests and devices (such as literacy tests) in states

not covered by the Voting Rights Act and, most important,

the possibly ineffective administration of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 will still result in the reduction of the basis

of apportionment of certain states if §2 is enforced in 1970.

It would be lacking in fairness to reject the standing of

appellants on the basis of new legislation, not considered

below, while at the same time holding appellants to plead

ings drafted prior to the passage of the statute on which

reliance is placed. The philosophy of pleading of the Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure is contrary to such a dis

position; Group I appellants are entitled to consideration

of their claim of injury due to nonenforcement of §2 in the

broadest possible context. Rather than such a disposition

the Court should at the least remand to the District Court

in order to permit Group I appellants to amend their plead

ing to show persistence of denial or abridgment of the

11

right to vote and the manner they are thereby injured.

Cf. American Comm, for Protection of Foreign Born v.

Subversive Activities Control Board, 380 U. S. 503, 505.

See Report of the President’s Commission on Registration

and Voting Participation (November, 1963) which de

scribes the denial and abridgments of the franchise which,

combined with other factors, keeps more than 40% of the

eligible voters of this country from exercising their right

to vote. Many of the denials of the franchise discussed in

this Report reduce the basis of apportionment within the

meaning of §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Of course, appellants do not favor such a remand. It is

their position, for reasons stated elsewhere in this reply

brief and in appellants’ brief, that Group I and Group II

appellants clearly have standing and that the case should

be remanded for a full trial. If, however, the Court accepts

appellees’ theory of the effect of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, it is respectfully submitted that Group I appel

lants are entitled to amend their pleading..

II.

This Controversy Is Justiciable.

The overriding purpose of the Census and Apportion

ment Act of 1929, which with minor modifications governs

apportionment today, was to delegate responsibility for

decennial apportionment. Appellants urged below that the

Act be construed in accordance with the Constitution and

that this suit not be dismissed on the ground of supposed

interference with Congress. The district court rejected

appellees’ theory that this suit posed a non-justieiable

“ political question,” for in its alternative holding, the Court

construed the Census and Apportionment Act, although

12

not in the manner urged by appellants. Appellees, how

ever, raise the question of justiciability once more, neces

sitating consideration of the issue.

For all the potential consequences of this litigation, the

conflicts which call for application of the political question

doctrine are simply not present in this case. Appellees are

Executive officers with total statutory authority to com

plete a decennial apportionment of representatives which

becomes the apportionment if Congress fails to act. A

declaratory judgment setting forth their responsibility to

comply with constitutional requirements when carrying out

their functions with respect to apportionment does not in

volve a conflict with Congress to which the “political ques

tion” doctrine applies (at least no more so than any

declaration of the duties of administrative officials in light

of constitutional provisions).

First, any doubts with respect to the lack of application

of the “political question” doctrine to this case should be

resolved by reference to the views of the Justice who may

be the foremost exponent of the doctrine on the present

Supreme Court. In a number of cases decided June 15,

1964, the Court held that the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment requires the states to struc

ture their legislatures so that they reflect population and

the members of both Houses represent substantially the

same number of people. Other factors may be considered

only to the extent that they do not significantly encroach

on the basic population principle. Mr. Justice Harlan dis

sented in these cases. Previously he had registered dissent

relying, in part, on the “ political question” doctrine in

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U. S. 1; Gray v. Sanders, 372

U. S. 368; and Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186. In his June 15,

1965 dissenting opinion, however, see Reynolds v. Sims,

13

377 U. S. 533, 589, lie relied on the remedy provided by

§2 of the Fourteenth Amendment to dispute the majority’s

view that the equal protection clause of §1 of the Four

teenth Amendment prohibited legislative districting which

did not provide for equivalent population:

Whatever one might take to be the application to these

cases of the equal protection clause if it stood alone,

I am unable to understand the Court’s utter disregard

of the second section which expressly recognizes the

states’ power to deny “ or in any way” abridge the

right of their inhabitants to vote for “ the members

of the [State] Legislature” and its express provision

of a remedy for such denial or abridgment. The com

prehensive scope of the second section and its par

ticular reference to the State Legislatures preclude

the suggestion that the first section was intended to

have the result reached by the Court today. (Emphasis

supplied.) (Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. at 594.)

It is of great significance that the sole Justice who dis

sented in Baker v. Carr, supra; Cray v. Sanders, supra;

and Wesberry v. Sanders, supra, takes the view that §2 of

the Fourteenth Amendment provides a comprehensive

“ remedy” for malapportionment, for he may be the strictest

adherent of the theory proposed by defendants with respect

to the justiciability of this case.

Second, appellees’ argument with respect to nonjusticia

bility is put to rest conclusively by Wesberry v. Sanders,

supra. It is difficult to understand upon what theory courts

would be dealing with a “political question” when declaring

that officials of the Executive branch have a duty to ap

portion in accordance with ^2 (or that provisions of the

Census and Apportionment Act which fail to authorize

14

such apportionment are unconstitutional), and not be deal

ing with a “ political question” when holding that repre

sentatives in Congress must be elected from congressional

districts drawn so that one man’s vote is worth as much

as another’s and providing a judicial remedy to enforce

this right. In Wesberry, supra, 376 U. S. at 6, 7, the

court stated explicitly that cases involving congressional

apportionment are justiciable. Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s

argument in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549, was re

jected. The areas wherein the “political question” doctrine

still lives are described at length in Baker v. Carr, 369

U. S. 186, 211, but none of the situations or cases described

in that opinion compare to this case. If appellants are

not entitled to relief, or are only entitled to a part of the

relief they seek, then such should be the decision of this

case on the merits, not the basis for refusal to deal with

the great constitutional provision before the Court. Sec

tion 2, in short, should be construed; not relegated to a

vacuum where its meaning and effect are to be perma

nently undecided.

Third, appellees lay stress on the fact that while §2 of

the Fourteenth Amendment sets out the conditions calling

for the reduction of a state’s representation, it does not

specify how to go about determining whether such condi

tions exist. In so doing they ignore the express allegations

of the complaint that determination of the extent of denial

and abridgment of the franchise is a matter which the

Census Bureau can determine with no greater difficulty than

it experiences in other census inquiries. Congress, for ex

ample, does not specify how to go about determining

whether and to what extent “ unemployment” exists within

the meaning of a number of federal statutes. This is a

matter which is determined by the Bureau of the Census.

15

Appellants filed in the court below a long and detailed

affidavit from an eminent statistician, and former official

of the Bureau, stating that the affidavit of former Director

of the Bureau of the Census, Bichard M. Seammon, filed by

appellees, was incorrect and misleading in its substantial

and material allegations. Dr. A. ,J. Jaffe concluded that

the Bureau could make the determinations required for

enforcement of §2 with accuracy, and, at oral argument in

the district court, appellees represented that as a practical

matter only adequate appropriations—never sought by ap

pellees— stand in the way of enforcement of §2. It is, there

fore, inappropriate for appellees to suggest, or for the court

to accept, a rule of decision in this case which assumes

facts contrary to the complaint or which accepts one affi

davit against the other. The argument of appellees’ brief

on this issue, at pp. 32-35, to the extent it challenges the

capacity of the Bureau of Census to enforce §2, is quite

beside the point. The alternative holding of the district

judge that summary judgment would be appropriate can

not be upheld on the basis of facts which are in dispute.

Fourth, appellees urge that enforcement of §2 requires

congressional action, that Congress has not implemented

it, and that, therefore, the court cannot reach the merits of

this controversy. This argument merely assumes the con

clusion it seeks the Court to adopt. The remainder of the

provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, as well as other

constitutional provisions, are applied by the courts to strike

down state action which violates their terms. Appellees,

for example, offer no meaningful distinction between §1

and §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Nor are questions involving the implementation of §2

non-justiciable because §2 is without standards. Broad con

cepts such as due process of law or equal protection of the

16

laws contain, in fact, fewer standards than §2. Section 2,

moreover, must be considered a far more likely candidate

for judicial enforcement than the due process or equal pro

tection clauses. To be sure, like all constitutional provi

sions it requires construction, but §2 is precise about the

result it commands. The legislators who formulated what

was to become §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment had a defi

nite end in mind. When compared to the vague and open-

ended due process and equal protection clauses (see the

discussion of §1 of the Fourteenth Amendment in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 489, 490) §2 is clearly

capable of construction and enforcement.

Section 2 also contains explicit standards when compared

to other provisions of the Constitution which are judicially

enforced. In Wesberry v. Sanders, supra, for example, the

Supreme Court struck down a congressional apportionment

on the basis of that portion of Art. 1, §2, Cl. 1 of the Fed

eral Constitution which states that Congressmen shall be

chosen “by the people of the several states” and construed

this provision to require, that as nearly as practicable, one

man’s vote in a congressional election must be worth as

much as another’s. It would be totally unreal and incon

sistent to hold that the Art. 1, §2, Cl. 1 provision requir

ing Congressmen to be chosen “by the people of the several

states” was judicially enforceable and that the provisions

of §2 of the Fourteenth Amendment were not.

The present apportionment process established by Con

gress, delegated to and carried out completely by the Execu

tive branch, provides for the decennial census count author

ized by Art. 1, §2, Cl. 3 of the Constitution. The Bureau of

Census counts the population in each state and certifies a

statement, not later than December 1 of the decennial year,

of the population in each state and the number of repre

17

sentatives to which each state would be entitled under an

apportionment of the existing number of representatives

by the mathematical method known as the method of equal

proportions, 2 U. S. C. §2a; 13 U. S. C. §141. Within 15

calendar days after the statement has been delivered to

the Congress by the President, the Clerk of the House of

Representatives sends to the Governor of each state a cer

tificate showing the number of Representatives to which

his state will be entitled at the beginning of the following

Congress.

Under this apportionment procedure there is no lack of

opportunity on the part of appellees to comply with the

constitutional requirements of §2. Once the facts of denial

and abridgment are gathered, the statement need only be

completed by taking them into account. To the extent ac

tual disfranchisement statistics, or the actual apportion

ment of Representatives, dissatisfies the Congress that

body may refuse to accept any apportionment based thereon

and may reapportion itself, for the relief appellants seek

does not interfere with the power of Congress to reap

portion or to amend the present apportionment scheme.

18

III.

Title VIII of the Civil Rights. Act of 1964 Is Not

Pertinent to Decision of This Case.

Appellees also urged that Title V III of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 286, which authorizes the collection

of certain statistics, shows that Congress has sought to

enforce §2 only in the manner provided by Title V III.2

This position is not well taken. Analysis of its text reveals

that it is impossible to enforce §2 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment with information gathered under authority of Title

VIII.

First, Title V III relates only to certain geographical

areas and, therefore, as §2 requires a national measure

ment of denial or abridgment of the right to vote, is to

tally incapable of serving as a vehicle to enforce §2 of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

2 “ The Secretary of Commerce shall promptly conduct a survey

to compile registration and voting statistics in such geographic

areas as may be recommended by the Commission on Civil Rights.

Such a survey and compilation shall, to the extent recommended

by the Commission on Civil Rights, only include a count of per

sons of voting age by race, color, and national origin, and determi

nation of the extent to which such persons are registered to vote,

and have voted in any statewide primary or general election in

which the Members of the United States House of Representatives

are nominated or elected, since January 1, 1960. Such information

shall also be collected and compiled in connection with the Nine

teenth Decennial Census, and at such other times as the Congress

may prescribe. The provisions of section 9 and chapter 7 of title 13,

United States Code, shall apply to any survey, collection, or com

pilation of registration and voting statistics carried out under

this title: Provided, however, that no person shall be compelled

to disclose his race, color, national origin or questioned about his

political party affiliation, how he voted, or the reasons therefore

[sic], nor shall any penalty be imposed for his failure or refusal

to make such disclosure. Every person interrogated orally, by

written survey or questionnaire or by any other means with respect

to such information shall be fully advised with respect to his right

to fail or refuse to furnish such information.”

19

Second, Title V III is limited to information concerning

racial discrimination. Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment includes all denial or abridgment of the franchise.

Third, Title V III does not permit Census to compel

respondents to answer as opposed to traditional Census

legislation (13 U. S. C. §221) and, therefore, may well

be ineffective in even obtaining the limited information

sought by its terms.

Fourth, Title V III is limited to questions relating “ only”

to the number of persons registered or not registered and

does not by its terms admit questions going to the causes

of non-registration. Clearly, without the reasons for non

registration being obtained, §2 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment cannot be enforced.

The legislative history, moreover, supports the inference

that the dominant purpose of Title V III was to provide

statistics which would help the Congress enact legislation

with respect to and to appraise the success of voting leg

islation such as the Civil Bights Acts of 1957 and 1960 and

Title I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. See 42 U. S. C.

§§1971 et seq. For example, Attorney General Kennedy

testified before the full Judiciary Committee with respect

to Title V III that “ such a survey should prove helpful to

the Congress in assessing the dimensions of discrimination

in voting and aid in measuring the pace of progress in its

elimination.” Hearings before the House Committee on the

Judiciary on H. R. 7152, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. ser. 4, part 4

at 2661 (1963). Indeed, Congressman McCulloch who in

troduced Title V III (H. R. 3139; see Hearings, id., at p. 69)

did not mention §2 at all and stressed that lack of regis

tration statistics hampered fact-finding by the Civil Rights

Commission and Department of Justice voting discrimina

20

tion suits. See Additional Views on H. R. 7152, U. S. Code

Congressional and Administrative News (July 20, 1964)

pp. 1889, 1890. The majority report of the Judiciary Com

mittee gives no particular reason for the inclusion of Title

V III other than what is apparent from the Title’s lan

guage, and the minority report similarly fails to mention

§2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The legislative history of Title V III does not establish

the propositions for which defendants cite it, for there is

no indication in the legislative history of Title V III that

any Congressman thought it would affect the existing ap

portionment scheme. To be sure, certain Congressmen,

hopeful of a complete and full enforcement of §2 of the

Fourteenth Amendment, supported Title V III on the

grounds that it was a step in the right direction, but the

legislative history is barren of any indication that they,

or opponents of Title VIII, considered it to substitute for,

or in any manner affect, the statutory scheme formulated

in the Census and Apportionment Act of 1929. At the most,

they saw Title V III as relating to (without articulating

the relationship) congressional enforcement of §2, some

thing appellants do not contend Congress cannot do in

ways other than that which can arise from judicial en

forcement of law predating Title VIII.

Appellees, however, asked the Court to avoid construc

tion of the 1929 Census and Apportionment Act on the

sub silentio assumption of certain Congressmen in 1964

that the 1929 Act did not effectively enforce §2. The in

adequacy of this argument is demonstrated by the fact

that the Bureau of the Census has failed to enforce §2

in the years subsequent to 1929. It is, therefore, quite

obvious that Congressmen interested in enforcing §2 might

21

support any measure related to collection of voting sta

tistics as a step in the right direction. Their support of

Title V III tells us only that §2 has not in fact been en

forced, not their view as to whether the Bureau of Census

has been authorized to enforce it.

Statutes, moreover, are construed with reference to cir

cumstances existing at the time of their passage and not

on the basis of what subsequent Congresses may have

thought them to mean. In other words, unless the Congress

enacting Title V III sought to amend the pre-existing census

and apportionment scheme (and appellees do not make

this claim), no inference may be drawn from its passage

which could be taken to alter that scheme. A number of

decisions of the United States Supreme Court establish

this proposition beyond dispute. In Rainwater v. United

States, 356 U. S. 590 (1958), the question before the Court

was whether the term “ the Government of the United

States” as used in the False Claims Act included the

Commodity Credit Corporation. The False Claims Act

was enacted in 1863 and later amended in 1918 to apply

explicitly to corporations in which the United States was

a stockholder. It was argued that the 1918 amendment

showed that the Act had not previously covered govern

ment corporations. This contention was rejected by a

unanimous Court: “At most, the 1918 Amendment is merely

an expression of how the 1918 Congress interpreted a stat

ute passed by another Congress more than a half a century

before. Under these circumstances such interpretation has

very little significance.” Id. at p. 593. (Emphasis supplied.)

The point is made with equal force in United States v.

Muniz, 374 U. S. 150,158 n. 14 (1963) and in United States

v. Wise, 370 U. S. 405, 411 (1962) and the cases cited

therein.

22

In conclusion, construction of 2 U. S. C. §2(a), 13 U. S. C.

§141, and the entire statutory scheme which governs ap

portionment cannot be avoided on the basis of inferences

culled from the legislative history of Title V III of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam C. Gardner

615 “ F ” Street, N.W.

Washington, I). C.

J ack Greenberg

J ambs M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

R ichard L. Banks

W illiam R. Ming, Je.

S. W . T ucker

A. P. T ureaud

A. W . W illis, Jr.

Margaret B ush W ilson

Of Counsel

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on November 1965, I served

copies of the foregoing Motion for Leave to File Reply

Brief and Reply Brief on attorneys for appellees, John

Douglas, J. William Doolittle, Richard S. Salzman, at the

Department of Justice, Washington, D. C. by depositing

same in the United States Mail, airmail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

<̂ m§i§» 38