Supplemental Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1990 - November 30, 1990

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Supplemental Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1990. b54db730-f211-ef11-9f89-0022482f7547. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76b1b247-1822-425a-94ad-e6340d05a3ed/supplemental-appendix-to-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

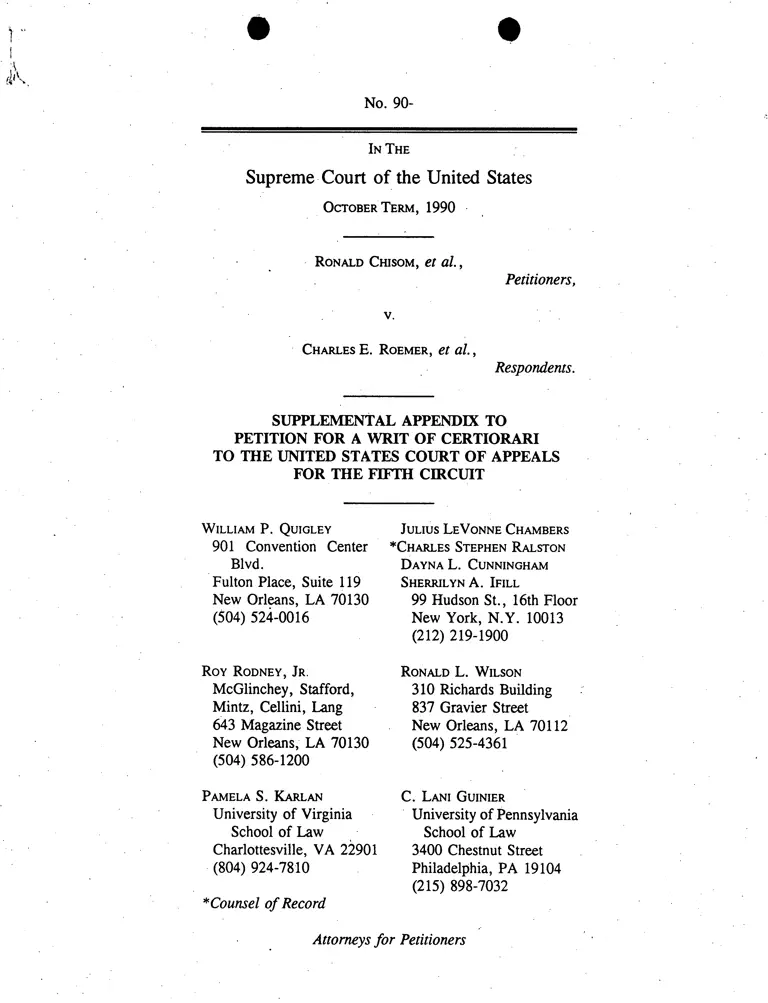

No. 90-

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1990 •

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Petitioners,

V.

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al.,

Respondents.

SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX TO

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center

Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

McGlinchey, Stafford,

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

*Counsel of Record

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

*CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. WILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LANI GUINIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

The Tables included in this Supplemental Appendix to

the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari in this case are those

referred to in the opinion of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana set out in the Appendix

to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari at pp. 4a-64a.

TABLE 1

Judicial Offices Elected on a parish-Wide Basis

in the

First Supreme Court District

Number of Number of

Parish Court of.judges black judges

Jefferson District 24 15

Juvenile 3

Orleans Civil 12 3

Criminal 10 0

Juvenile 0 5 1

Crim. Magistrate 1 0

Municipal 4 1

Traffic 0 4 1

Plaguemines District 25 2 0

St. Bernard District 34 3 6

Orleans 4th Circuit,

Plaguemines at-large

St. Bernard (court of appeal) 2 0

Orleans 4th Circuit,

1st District

(court of appeal)

Plaguemines 4th Circuit,

2nd District

(court of appeal)

St. Bernard 4th Circuit,

3rd District

(court of appeal)

Jefferson 5th Circuit,

1st District

(court of appeal)

8 01

1

6

0

New Orleans

Municipal

New Orleans

Traffic

New Orleans

First City

Jefferson

Juvenile

TOTAL

V Circuit

Dist. 1

TABLE 2

Election of Minority Candidates

Contested Elections for Judicial Positions

in the First Supreme Court District (1978-88)

Percentage of Number

Elections Where Total Black

Judgeship/ Winner is Preferred Number of vs. White

District by Minority Bloc Elections Elections

Supreme Ct.

Dist. 1 100% 3 0

24th 71% 7 1

25th 100% 1 0

34th 100% 4 0

Orleans Civil 56% 9 6

Orleans Crim. 29% 7 3

IV Circuit

At-Large 0 0

IV Circuit

Dist. 1 75% 4 1

IV Circuit

Dist. 2 75% 4 0

IV Circuit

Dist. 3 100% 3 0

0% 1 0

Orleans Juvenile 20% 5 5

75% 4 2

100% 2 1

50% 4 2

0% 1 1

62.7% 59 21

TABLE 3

Ecological Regression Analyses 2- for 34 Elections2

Percent of Vote for

Black Candidate

Black

Election Candidate Office

ORLEANS PARISH

Black White

Voters Voters

1978

Primary Wilson Criminal Mag. 32 2

Primary Douglas Juvenile Ct. Sec. B 57 3

Young Juvenile Ct. Sec. B 24 2

1979

Primary Ortique Civil Dist. Div. H 97 14

General *Ortique3 Civil Dist. Div. H 99 13

Primary Young Juvenile Ct. Sec. E 65 5

General Young Juvenile Ct. Sec. E 80 25

Primary Pharr 1st City Ct. Sec. C 6 2

1980

Primary Young 1st City Ct. Sec. A 72 4

General Young 1st City Ct. Sec. A 92 15

1 This table is set forth in Pre-trial Order Stipulation 78,

pp. 48-50. Voter sign-in data, by precinct and by race, is not

available from the State of Louisiana for elections conducted

prior to January 1, 1988.

2 The elections in bold print are outcome determinative

elections. An "outcome determinative election" is an election in

which a candidate is elected to fill the position at issue.

Black candidates have participated in 23 of the 57 outcome

determinative elections held for contested judicial positions in

the first district since 1978. A black candidate was successful

in 6 of these 23 outcome determinative elections.

3 "*" Indicates a winning candidate.

1981

Primary Thomas 1st City Ct. Sec. C 94 17

1982

Primary Julien Crim. Dist. Div. I 39-41 4-5

Wilson Crim. Dist. Div. I 31 3

General Julien Crim. Dist. Div. I 88 16

1983

Primary - Davis Civil Dist. Div. D 97 - 6-7

1984

Primary Dorsey Civil Dist. Div. F 51-52 23

Primary *Johnson Civil Dist. Div. I 85 30

Primary Young Juvenile Ct. Sec. C 46 5

Primary Douglas Ctim. Dist. Div. B 72-74 6-7

General Douglas Crim. Dist. Div. B 88 11

Primary Dannel Juvenile Ct. Sec. A 20 19

Gray Juvenile Ct. Sec. A 69 10

General *Gray Juvenile Ct. Sec. A 96 16

1986

Primary Blanchard Crim. Dist. Div. J 72-75 13-15

Primary Magee Civil Dist. Div. F 75 9-10

Wilkerson Civil Dist. Div. F 22 35

General *Magee Civil Dist. Div. F 92 12-13

Primary Dannel Juvenile Ct. Sec. D 84 21

Primary McCondult Municipal Ct. 71 12

General *McConduit Municipal Ct. 84 27

1987

Primary Douglas 4th Cir. Court of 53-54 21-22

Appeal, Dist. 1

1988

Primary Hughes Civil Dist. Div. G 35 3

General Hughes Civil Dist. Div. G 83-85 9

Primary Julien Municipal Ct. 62-64 14

Primary Dannel Traffic Ct. 48-49 23

Hughes Traffic Ct. 35-36 11

General *Dannel Traffic Ct. 76-77 34

JEFFERSON PARISH

1987

Primary Council Juvenile Ct. Div. A 81-82 3

1988

Primary Zeno District 24 Div. L 100-104 15-18

•

TABLE 4

Black Delegates to 1973 Constitutional Convention

AVERY C. ALEXANDER, Vice Chairman of the Convention, Dele-

gate elected from Legislative District 93 (Kenner, Jefferson

Parish, Louisiana)

GEORGE DEWEY HAYES, Delegate elected from Legislative Dis-

trict 63 (Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana)

J. K. HAYNES, Delegate appointed to represent public at

large. (Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana)

ALPHONSE JACKSON, JR., Delegate elected from Legislative

District 2 (Shreveport, Caddo Parish, Louisiana)

JOHNNY JACKSON, JR., Delegate elected from Legislative Dis-

trict 101 (New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana)

LOUIS LANDRUM, SR., Delegate elected from Legislative Dis-

trict 91 (New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana)

ANTHONY MARK RACHAL, JR., Delegate appointed to represent

the Civil Service (New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana)

NOVYSE E. SONIAT, Delegate elected from Legislative District

88 (Metairie, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana)

DOROTHY MAE TAYLOR, Delegate appointed to represent Racial

Minorities (New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana.

THOMAS A. VELAZQUEZ, Delegate elected from Legislative Dis-

trict 97 (New Orleans, Orleans Parish Louisiana)

GEORGE LiaiLL WARREN, Delegate elected from Legislative Dis-

trict 102 (New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana)

MARY E. WISHAM, Delegate elected from Legislative District

No. 67 (Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana)

TABLE 5

1972 Special Elections Results

for the Two Seats

from the First District

Candidate Total vote (%)

Ortique (B) 27,648 (14.0)

Calogero 67,256 (34.1)

Redmann 22,262 (11.3)

Sarpy 79,796 (40.5)

196,962

Orleans vote (%)

21,744 (20.7)

• 34,473 (32.8)

10,542 (10.0)

38,256 (36.4)

105,015

Orleans vote as

a proportion of

the total vote

78.6

51.3

47.4

47.9

53.3

Amedee (B)

Marcus

Borsetta

Garrison

Samuel

11,872 ( 5.8)

78,810 (38.7)

35,272 (17.3)

52,249 (25.7)

25,476 (12.5)

203,679

8,997 ( 8.4)

46,629 (43.4)

-19,728 (18.4)

26,055 (24.2)

5,994 ( 6.6)

107,403

75.6

59.2

• 55.9

49.9

• 23.5

52.7

TABLE 6

Secretary of State Results in 1987 Primary

for Parishes in the First Supreme Court District

Candidate Jefferson Orleans Plaquemines St. Bernard Total Pct.

Cutshaw 24,097 12,936 1,564 5,854 43,911 14.7

Lombard 27,081 71,146 2,002 4,026 104,255 35.0

McKeithen 41,091 29,613 2,680 11,452 84,836 28.5

Rivers 1,233 2,889 111 365 4,598 1.5

Tassin 16,039 6,545 925 2,877 26,386 8.9

Others 17,789 10,802 1,396 4,102 34,089 11.4

Source: Official Return from Louisiana Office of Secretary of State

TABLE 7

Orleans Parish

Election Results for Parish-Wide Offices

Involving Black vs. White Candidates

Weighted Regression Analysis

1980-1988 4

Date of % Black % White

Election Office Candidates Vote Vote

09-13-80 School Galman (B) 21.6 2.5

Board (2) *Koppel 12.0 41.7

*Spears (B) 26.0 20.5

Watson 2.7 9.6

*Zanders (B) 26.3 7.2

White Others 2.0 8.8

Black Others 9.4 .3.9

02-06-82 Civil Bush (B) 6.9 1.9

Sheriff *D'Hemecourt 15.1 42.8

Ivon 8.5 33.2

*Valteau (B) 69.5 22.1

Mayor Ali 0.3 0.2

*Faucheaux 0.3 80.5

Fertel 0.2 0.5

Jefferson (B) 8.0 6.2

*Morial (B) 90.8 12.6

Waters (B) 0.3 0.2

Councilman *Barthelemy (B) 52.7 26.7

At-Large (2) Dee 1.9 6.1

*Giarrusso 32.9 42.1

Koppel 12.5 25.1

4 The information contained in this table is taken from

Weber's Report, Defendants' Exhibit 2, pp. 33-37 and Appendices C

and E and Engstrom's Report, Plaintiff's Exhibit 1, Table 1. "*"

designates a winning candidate. Weber's Report sets forth both

weighted and unweighted regression analyses and. a homogenous

precinct analysis. Engstrom's report provides both analyses for

black judicial candidates. The Court has considered statistics

produced by all three analyses, but has chosen to set forth here

only the weighted regression analysis for illustrative purposes,

given that all three analyses produced figures appearing

relatively similar and weighted regression analysis appears to

take more variables into consideration in most instances. See

Weber, pp. 10-13, Engstrom Report, pp. 3-5.

•

,

03-20-82

09-11-82

11-02-82

06-18-83

• 09-29-84

Criminal

Dist. Ct.

(Div. I)

Civil

Sheriff

Mayor

Criminal

Dist. Ct.

(Div. I)

School

Board (2)

School

Board (1)

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Dist. D)

U.S. Congress

(Dist. 2)

School

Board (1)

District

Attorney

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Div. F)

*Julien (B)

Kogos

Meyer

Scaccia

Wilson (B)

*Wimberly

D'Hemecourt

*Valteau (B)

Faucheaux

*Morial (B)

Julien (B)

*Wimberly

Jeffrion (B)

Lombard (B)

*Loving (B)

*McKenna (B)

Pope

Rittiner

*Robbert

McKenna (B)

*Robbert

Davis (B)

*Di Rosa, L.

Augustine (B)

*Boggs

Morrison

Lodrig (B)

Torregano (B)

Beverly

Charitat

*Glapion (B)

*Higbee

Hirsch

Lombard (B)

West (B)

Zanders (B)

*Connick

Marcal

Reed (B)

Dorsey (B)

*Roberts

39.3 4.2

- -

01•0

31.3

12.7 50.2

3.2

13.0 65.9

87.0 34.1

1.6 86.3

98.4 13.7

88.1 16.3

12.3 83.6

6.7

11.1

47.5

32.0

0.2

0.1

1.5

3.4

5.2

21.0

9.4

11.8

22.9

26.3

91.4 16.8

8.6 83.2

97.0 6.6

2.8 93.5

64.4

34.5

0.4

0.4

0.1

1.9

1.9

49.0

1.2

0.2

6.1

0.8

38.9

13.5

1.6

84.9

7.6

90.7

0.6

0.5

0.6

3.6

9.9

6.3

56.4

4.6

3.8

1.5

13.9

89.0

2.8

8.2

51.6 23.2

49.1 76.7

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Div. I)

Harris

*Johnson (B) 84.9

09-29-84 Criminal *Douglas (B) 72.1

Dist. Ct. Myers --

(Div. B) *Quinlan 6.7

Juvenile Dannel (B) 19.7

Court *Gray (B) 69.0

(Div. A) *Horton - 4.1

Martin

Juvenile Ducote

Court *Mule 41.8 64.5

(Div. C) Young (B) 46.2 4.7

11-06-84 School *Glapion (B) 97.2 15.6

Board (1) Higbee 2.8 84.4

Criminal Douglas (B) 88.3 10.4

Dist. Ct. *Quinlan 12.0 89.1

(Div. B)

30.0

6.0

67.0

18.7

9.6

67.8

•Mi 1=1"

Juvenile *Gray (B) 95.7 16.2

Court Horton

(Div. A)

OMP 4111•1

02-91-86 Criminal Aubrey (B) 10.6 5.3

Sheriff *Foti 76.7 82.7

Ghergich 12.7 12.0

Civil Begg 2.6 9.3

Dist. Ct. Ciamarra 2.2 12.6

Clerk Douglas (B) 43.4 6.6

*Foley 51.8 71.5

Criminal Carroll 5.8 31.9

Dist. Ct. *Lombard (B) 94.2 68.1

Clerk

Recorder of

Mortgages

Bogan (B)

*Demarest

54.2

45.8

10.7

89.3

Registrar of *Lewis (B) 48.0 6.2

Conveyances Merrity 10.9 6.8

*Schiro 27.2 57.4

Watermeier 13.9 29.6

02-01-86 Mayor *Barthelemy (B) 24.4 42.1

Hardy 0.3 0.2

*Jefferson (B) 71.0 7.2

LeBlanc lA 48.7

• Lombard-(B) 3.1 1.5

Rauch 0.2 0.3

03-01-86

09-29-86

11-04-86

10-24-87

03-08-88

Councilman

At-Large (2)

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Div. F)

Criminal

Dist. Ct.

(Div. J)

Registrar of

Conveyances

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Div. F)

School

Board (2)

Municipal

Court

Judge

Juvenile

Court

(Sec. D)

School

Board (1)

Municipal

Court

Judge

4th Circuit

1st Dist.

Civil

Dist. Ct.

(Div. G)

*Bagneris (B)

Detweiler

*Giarrusso

Kent

*Taylor (B)

Williams (B)

*Hawkins

*Magee (B)

Wilkerson (B)

Blanchard (B)

*Cannizzaro

Lewis (B)

*Schiro

Hawkins

*Magee (B)

Evans (B)

*Koppel

xLambert-Busshoff

Lombard (B)

*McKenna (B)

Williams (B)

Zanders (B)

White Others

Black Others

*Comarda

Fitzsimmons

*McConduit (B)

Dannel (B)

*Lagarde

*McKenna (B)

Lambert-Busshoff

Comarda

*McConduit (B)

Douglas (B)

*Plotkin

Barnett

Cresson

Exnicios

*Giarrusso

*Hughes (B)

36.0

0.6

24.0

0.4

33.4

5.6

3.4

75.0

21.8

8.1

28.3

34.8

14.1

6.8

7.9

55.6

9.5

34.6

74.7 15.0

27.7 86.8

74.3 17.2

25.7 82.8

r=1, MID

91.5 12.4

25.3

11.4

1.1

5.9

21.3

12.7

13.2

0.5

8.6

4.9

42.7

27.2

2.7

9.3

5.6

3.2

1.8

2.6

17.0 58.6

70.8 11.8

84.1 21.0

16.2 78.9

89.3 24.0

10.7 76.0

•••

84.2 26.5

54.0 22.2

47.2 78.7

11•11.

- -

- 411•6

47.8 39.7

35.8 3.4

04-16-88 Civil *Giarrusso

Dist. Ct. Hughes (B)

(Div. G)

16.7

84.6

91.5

9.1

10-01-88 Municipal Ct. *Glancey 36.2 85.5

Judge SJulien (B) 62.4 13.5

Traffic Ct. *Dannel (B) 48.7 22.9

Judge *Hassinger 15.1 65.8

Hughes (B) 35.4 11.1

School Board Gagliano 22.5 30.2

(2) *Koppel 25.8 41.3

*McKenna (B) 51.7 28.5

11-08-88 Traffic Ct. *Dannel (B)

Judge nassinger

77.0 34.4