Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 16, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. a207c584-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76ccde4e-1ff8-4ffa-9e1b-367aa7f0d3bf/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

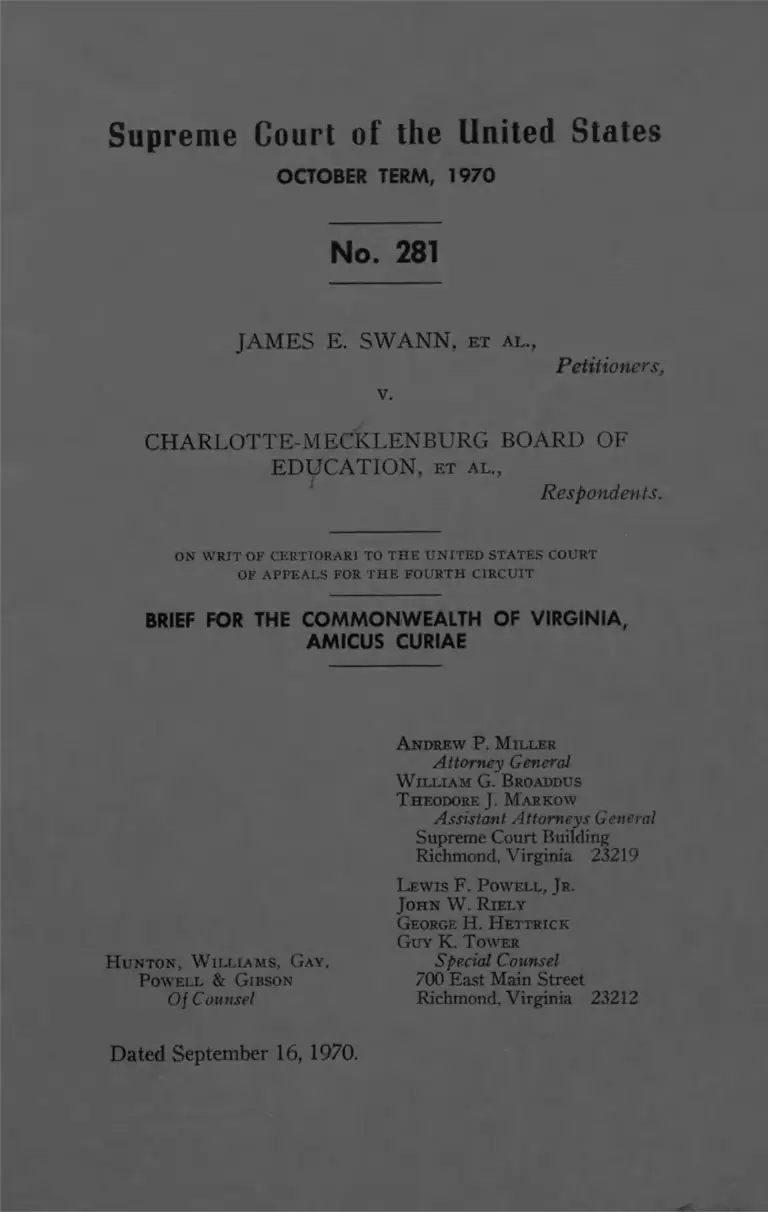

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

No. 281

JAMES E. SWANN, et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et a l .,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITE D STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR T H E FOURTH CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

AMICUS CURIAE

H u n t o n , W il l ia m s , G ay ,

P ow ell & G ibson

0 / Counsel

A ndrew P . M iller

Attorney General

W il l ia m G. B roaddus

T heodore J . M arrow

Assistant Attorneys General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

L e w is F. P ow ell , J r .

J o h n W . R iely

G eorge H . H ettrick

Guy K. T ower

Special Counsel

700 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23212

Dated September 16, 1970.

Printed Letterpress by

LEWIS PRINTING COMPANY

Richmond, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I . I ntrod uction .................................................................................. 1

II. T h e I nterest Of V i r g i n ia .......................................................... 1

III. T h e I ssu e B efore T h e C o u r t ............................................... 6

IV. S u m m a r y O f A r g u m e n t ....................................................... 6

V. A r g u m en t ................................................................................ 8

A. The Origin Of Racial Segregation Is Irrelevant............. 8

B. Racial Balance Is Not Required....................................... 10

C. The Highest Quality Of Education Must Be The Goal .. 17

D. The Court Below Misapplied Its Rule Of Reason......... 20

VI. C o n c lu sio n .... ....................................................................... 26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1968) ..2, 11

Atkins v. School Bd., 148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D.Va. 1957), aff’d

246 F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855

(1957).......................... .................... ........................................ . 1

Beckett v. School Bd., 308 F. Supp. 1274 (E.D.Va. 1969) ....9, 11, 22

Beckett v. School Bd., Civil Action No. 2214 (E.D.Va., Aug.

14, 1970) ........................................................ ....................... 20, 22

Beckett v. School Bd., Civil Action No. 2214 (E.D.Va., Aug.

27, 1970) ............................. - ....................................................... 2

Bell v. School City, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

377 U.S. 924 (1964)..................................................................... 8

Blocker v. Board of Educ., 229 F. Supp 709 (E.D.N.Y. 1964) _ 10

i

Page

Bradley v. School Bd., Civil Action No. 3353 (E.D.Va., Aug.

17, 1970) ............................................................... ........................2, 3

Brewer v. School Bd., No. 14,544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970), cert,

denied, 38U.S.L.W. 3522 (U.S. June 29, 1970) (No. 1753)..3, 10

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

1, 11, 15, 16, 18, 19, 24

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ................... 1, 12, 24

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, No. 14,571 (4th Cir., June 5, 1970)

13, 15, 26

Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396 U.S. 290 (1970) ....... 11

Crawford v. Board of Educ., No. 822, 854 (Cal. Super. Ct.,

Feb. 11, 1970) ............................................................................... 21

Daniels v. School Bd., 145 F. Supp. 261 (E.D.Va., 1956) ......... 1

Davis v. County School Bd., 103 F. Supp. 337 (E.D.Va., 1952) .. 1

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967) ....................................... 8, 9, 24

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ........... 2, 11, 12

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967), aff’d sub

nom., Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C.Cir. 1969) ___ 17

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D.Va. 1959), appeal

dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959) ................................................. 1

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 397 U.S. 232 (1970) ................... 12

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 511 (1925) ........................... 15

Thompson v. County School Bd., 144 F. Supp. 239 (E.D. Va.

1956), aff’d sub nom. School Bd. v. Allen, 240 F.2d 59 (4th Cir.

1956), cert, denied, 353 U.S. 910, 911 (1957), opinion supple

mented, 159 F. Supp. 567 (1957), aff’d 252 F.2d 929 (1958),

cert, denied, 356 U.S. 958 (1958), injunction dissolved, 204

F. Supp. 620 (1962) __________________________________ 1

United States v. Montgomery Bd. of Educ., 395 U.S. 225 (1969) 12

»

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c(b) (1964) ............... 22

Education Appropriations Act of 1971, P.L. 91-380, 91st Cong.,

2d Sess., §§ 209, 210 (1970) ....................................................... 22

Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, 20 U.S.C.

§ 884 (1966), amending 20 U.S.C. § 884 (1965) ................... 22

S. 4167, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) ............................................. 10

A. Bickel, The Supreme Court and the Idea of Progress (1970) .... 10

Christian Science Monitor, Aug. 14, 1970 ....................................... 23

Civil Rights U.S.A.: Public Schools North and West, U.S.

Comm’n on Civil Rights (1962) ................................................. 16

R. Clark, Testimony before Senate Select Committee on Equal

Educational Opportunity (July 7, 1970) ................................... 9

Cohen, Defining Racial Equality in Education, 16 U.C.L.A.

L. Rev. 255 (1959) .............................................................. 18, 19

Coleman, The Concept of Equality of Educational Opportunity,

38 Harv. Educ. Rev. 7 (1968) ................................................... 19

J. Conant, Slums and Suburbs (1961) .......................................... 23

Desegregation of America’s Elementary and Secondary Schools,

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents (March 30,

1970) .............................................................................................. 21

Equality of Educational Opportunity, Office of Education, U.S.

Dept, of Health, Education and Welfare (1966) ............... 4, 18

Freund, Civil Rights and the Limits of Law, 14 Buffalo L. Rev.

199 (1964) .......................................................- ......................... 9

C. Hansen, Danger in Washington (1968) ................................ — 23

Kemer, et al., Report of the National Advisory Comm’n on Civil

Disorders (1968) ........................................................................... 16

N.Y. Times, Feb. 12, 1970...................................... - ......................... 21

Other Authorities

Page

Page

. . . 22

... 23

N.Y. Times, Sept. 13, 1970

N.Y. Times, Sept. 14, 1970

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, U.S. Comm’n on Civil

Rights (1967) ............................................................... 4, 9, 14, 25

United States Census of Population: 1960 Standard Metropolitan

Statistical Areas, Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Com

merce (1963) ................................................................................. 15

M. Weinberg, Desegregation Research: An Analysis (1968) ....23, 26

M. Weinberg, Race and Place, Office of Education, U.S. Dept, of

Health, Education and Welfare (1967) ..................................... 9

rr

INTRODUCTION

The Commonwealth of Virginia, because of the immedi

ate effect that the decision in this case will have on many

thousands of its citizens, requests the Court to consider

its views outlined in this brief. It seeks modification of the

opinions of both of the courts below and an expression of

principles that will guide all courts throughout the nation

in this most difficult area of basic human relationships.

n.

THE INTEREST OF VIRGINIA

In Virginia, segregation by race in the public schools

was required by constitution and statute prior to 1954. In

fact, one of the cases decided here under the style of Brown

v. Board of Education1 came to this Court from a Vir

ginia locality.2 3

It would be erroneous to assert that Virginia localities

welcomed Brown I and began at once to put into effect the

remedial steps required by Brown I I s; in most places they

did not. There was, instead, intense public opposition and

much delay. As a result, litigation arose in many communi

ties.4 The march toward what more recently has been termed

1 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

2 Davis v. County School Bd., 103 F. Supp. 337 (E.D.Va. 1952),

reversed by the Brown decisions.

3 349 U.S. 294 (1955).

* See, e.g., Thompson v. County School Bd., 144 F. Supp. 239

(1956), aff’d sub. nom School Bd. v. Allen, 240 F.2d 59 (1956), cert,

denied, 353 U.S. 910, 911 (1957), opinion supplemented, 159 F.

Supp. 567 (1957), aff’d 252 F.2d 929 (1958), cert, denied, 356 U.S.

958 (1958), injunction dissolved, 204 F. Supp. 620 (1962); Daniels

v. School Bd., 145 F. Supp. 261 (1956); Atkins v. School Bd.

148 F. Supp. 430 (1957), aff’d 246 F.2d 325 (1957), cert, denied,

355 U.S. 855 (1957); James v. Almond, 170 F.Supp. 331 (1959),

appeal dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959).

I.

2

a “unitary” system of public schools proceeded inexorably in

Virginia but, for a decade, it was an unwilling march

prodded by the courts of the United States.

It is now fair to say that Virginia localities* 6 are attempt

ing in good faith to comply with the mandate of the Equal

Protection Clause. But the courts have failed to make it

clear exactly what compliance entails. The dual system

must be replaced by a unitary school system,6 but how this is

to be accomplished is still far from apparent.

The result has been a chaotic condition in several of

Virginia’s school systems. Two of its largest school divi

sions, as the local systems are called, are located in Rich

mond and Norfolk, Virginia’s two largest cities. Litigation

affecting both of these cities has produced orders in August

of this year substantially rearranging school attendance

areas and inevitably requiring extensive pupil busing.7 This

has resulted in major disruption of public education and

confusion among white and black parents, students, faculty

and staff; it often has led to resentment and even fear.

The educational process is difficult enough without such

disruption. The time has come to think first of education

and the whole body of children to be educated. That, in our

view, can be accomplished only by the establishment by this

Court of the parameters within which school officials are to

act and by which their action is to be judged by the courts.

The factual situation existing in Charlotte, North Caro

lina, presents certain striking similarities to the situations

presented by Norfolk and Richmond. All three cities are

In Virginia local school boards, pursuant to the State constitution,

have the primary responsibility to operate the public schools.

6 Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968) ; Alex

ander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19, 21 (1968).

7 Bradley v. School Bd., Civil Action No. 3353 (E.D. Va., Aug.

17, 1970) (Richmond) ; Beckett v. School Bd., Civil Action No.

2214 (E.D. Va., Aug. 27, 1970) (Norfolk).

3

localities where, prior to 1954, segregation by race was re

quired by law. In all three, the percentage of black students

in the school population is significant, the 70% white and

30% black ratio of Charlotte becoming 60% white and

40% black in Norfolk and reversing to less than 40%

white and more than 60% black in Richmond.

Plans proposed by HEW and others presented by

the Norfolk and Richmond School Boards were rejected

because, the courts said, racial imbalance was not elimi

nated in sufficient degree.8 That result obtains equally in

this case from Charlotte. In each of these cases the court’s

solution was to require greater racial balance and, inevitably,

massive compulsory busing of students.

The question in those cases, as here, was whether racial

balance is an end in itself; if substantial racial balance must

be achieved, regardless of other educational factors that are

of significance in the situation presented, then the District

Courts were right in Charlotte and Richmond and the Court

of Appeals was right in Norfolk. If, as we urge, other

factors are also relevant, those courts were in error.

What will be decided here is, therefore, entirely relevant

in the two most critical Virginia situations. For that rea

son, the decision here may be determinative in Virginia.

Therein lies Virginia’s interest.

There are, of course, substantial points of difference be

tween Charlotte and the Virginia cities. The difference in

the racial mix has already been mentioned. This results

primarily from the fact that, by and large, the Norfolk and

Richmond school divisions are entirely urban rather than

both rural and urban as is the case in Charlotte. Norfolk is

8 Bradley v. School, Civil Action No. 3353 (E.D. Va., Aug.

17, 1970) (memorandum opinion) ; Brewer v. School Bd., No.

14,544 (4th Cir., June 22, 1970), cert, denied, 38 U.S.L.W. 3522

(U.S. June 29, 1970) (No. 1753).

4

adjoined by two cities, Chesapeake and Virginia Beach; in

them the percentage of black students is relatively small.

Richmond is bounded by two counties, Chesterfield and

Henrico; again their black student percentages are drasti

cally lower than is that of Richmond. As urban systems, the

two Virginia cities do not normally provide transportation

for pupils. The transportation problem presented by the

racial balance requirement is therefore more acute because

of the lack of facilities.

A brief word may be relevant as to the Norfolk and

Richmond plans that were rejected by the United States

courts. In both cities, the rejected plans provide for the

effective integration of all senior high schools and all junior

high schools or middle schools. In both plans, the respective

school boards go far beyond neutral or objective zoning

plans, gerrymandering natural attendance zones in a man

ner designed to increase the degree of integration in the

systems and to overcome the segregative effects of racial

residential patterns. Both plans include a majority-to-

minority transfer provision. The Richmond plan calls for

“learning centers” where weekly or bi-weekly interracial

educational experiences are to be provided for each child in

the system who attends a school with a population 90% or

more of the same race. Principles of the Norfolk plan were

explicitly based on the best available social science data, in

cluding the highly regarded research projects sponsored by

the U.S. Office of Kducation8 9 and the U.S. Commission on

Civil Rights.10

In sum, both plans adopt a neighborhood or community

concept in the sense that attendance areas for elementary

8 Equality of Educational Opportunity, Office of Education U.S.

Dept, of Health, Education and Welfare (1966).

10 Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, U.S. Comtn’n on Civil

Rights (1967).

5

schools are served by one or several schools and the advan

tages of convenience and close school-family relationships

are retained where practical. Overlaying this concept, how

ever, is the use in each plan of all feasible alternatives to

maximize integration. A number of subsidiary concepts,

such as pairing, consolidation and closing of schools, are in

corporated in the plans. No alternative plan was offered at

any hearing which would have the effect of increasing the

amount of desegregation that would result from the school

board plans, short of a plan which would require compul

sory massive busing to attain racial balance throughout each

system.

The question before the Virginia federal courts was,

accordingly, much the same as that presented in Charlotte:

is racial balance a constitutional requirement? The difficul

ties of busing in an urban system were presented to the

courts in both Virginia cases. The expense of initiation of

school transportation systems, a factor not present in Char

lotte, and the inadequacy of existing public transportation

systems were explored. The plaintiffs nevertheless sought

approval of plans requiring cross-busing, even of the

youngest children. Those plans, in essence, received ulti

mate judicial confirmation.

Virginia opposes racial balance as a constitutional require

ment. It believes that such balance must be considered; but

it should not be the controlling consideration. It seems to us

that racial balance alone was the determining factor in

Charlotte, Norfolk and Richmond. We suggest to the Court

that racial balance is not a desideratum in itself and that

this Court should declare the constitutional mandate to be

the best available quality of education for all regardless of

race or color.

6

THE ISSUE BEFORE THE COURT

The central issue before the Court is whether racial bal

ance is an end in itself, required by the Constitution with

out regard to other educational considerations or other

values.

III.

IV.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

A.

The Origin Of Racial Segregation Is Irrelevant

The proposition that one set of rules applies where the

origin of racial segregation was de jure and another where

the origin was de facto is without substance. History is

irrelevant to the enforcement of a constitutional right.

Racial segregation has almost everywhere received State

support. Thus no racial segregation is purely de facto.

Because the State maintains public schools, a segregated

system constitutes State action. Its existence, without regard

to its origin, thus raises a substantial constitutional ques

tion. The same rules must apply to non-unitary systems

wherever found.

B.

Racial Balance Is Not Required

Racial balance in the schools is not a constitutional im

perative. No decision of this Court has established such

a mandate. It is effective neither to accomplish integration

nor to improve education. Racial balance once prescribed

may be outdated by population shifts before it becomes ef

fective. The effort to attain racial balance promotes resegre

7

gation and movement to suburbia. These results defeat the

goal of racial balancing, adversely affect education and

contribute to urban deterioration.

C.

The Highest Quality Of Education Must Be The Goal

The goal of the desegregation movement must be to

achieve the highest quality of education. That has been the

thrust of previous decisions of this Court. Equal opportunity

is not to be measured purely by equality of resource appli

cation and racial balance; that system best conforms to the

constitutional mandate that provides, through equal oppor

tunity for every student, the highest level of achievement

for all students of every race, compensating appropriately

for any deficiencies that may have resulted from previous

racial segregation. The court below failed to recognize that

the best educational achievement for all is what the Consti

tution demands.

D.

The Court Below Misapplied Its Rule Of Reason

The court below unduly emphasized racial balance. It

also failed to recognize the relevance of the neighborhood

school and the disadvantages for all races of extensive

compulsory busing. The neighborhood school has obvious

social and educational advantages, particularly at the ele

mentary level. It can be used with a number of related tech

niques reasonably applied, without destroying neighborhood

advantages. Modern social scientists have developed many

considerations that ought to be taken into account in de

vising the plan that, giving weight to all relevant disparities,

best promotes the educational achievement of students of

all races.

8

V.

ARGUMENT

A.

The Origin Of Racial Segregation Is Irrelevant

In its consideration of the question presented here, the

Court of Appeals, in the plurality opinion, went to some

lengths to determine that the segregated pattern of housing

in Charlotte results from governmental action. We consider

this investigation irrelevant. We consider it more than irrele

vant ; it may be pernicious. It could lead to one set of rules

applying in one area of our nation and another set apply

ing in another. The constitutional right at issue here should

be available to all citizens without regard to the fortuitous

circumstance of the racial history of the places in which

they live.

An Unsound, Distinction

Such an investigation presupposes that one set of rules

applies where the origin of racial segregation was de jure

and another set where the origin was de facto. As an ex

ample of this distinction, reference is made to Deal v. Cin

cinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967). There, the Sixth Circuit

held that the school board has no duty to bus students

“. . . for the sole purpose of alleviating racial imbalance that

it did not cause . . . . ” (369 F.2d a t61).11

First, the question is not whether the State action is

limited to schools; it is a matter of State action in all phases

of race relationships such as public housing and zoning. In

this context, it is probable that all racial segregation in the

11 See also Bell v. School City, 324 F.2d 209 ( 7th Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1964).

9

United States, wherever occurring, has at some time been

maintained or supported by governmental action.12 Thus

there is no such thing as de facto segregation that is not of

de jure origin in some degree. The distinction purportedly

made in Deal cannot, then, be factually supported.13

State Action is Inevitable

But the vice lies deeper. Public schools are creatures of

the State, and a State may not continue to operate through

its local school boards or otherwise a system which denies

a constitutional right. Thus, a school system which denies

equal educational opportunity infringes protected rights.

Whether such a system was State created or State assisted

or merely State perpetuated is beside the point. If it de

prives children of equal educational opportunity, the Equal

Protection Clause is infringed.

Uniformity of Constitutional Rights

This conclusion is not only sound doctrine but desirable

public policy. If non-unitary school systems must be elim

inated because they perpetuate racial segregation, they must

be extirpated everywhere and not just in the former Con

federate states. A constitutional right ought not to be en

12 In Appendix C to his opinion, Judge Hoffman complied a sum

mary of governmental action in the various states. Beckett v. School

Bd., 308 F. Supp. 1274, 1304, 1311-15. See also Racial Isolation in The

Public Schools, U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights 245, 254-59 (1967); M.

Weinberg, Race and Place, Office of Education, U.S. Dept, of Health,

Education and Welfare (1967).

13 See Freund, Civil Rights and the Limits of Law, 14 Buffalo L.

Rev. 199, 205 (1964). On July 7, 1970, Ramsey Clark, former At

torney General of the United States, testifying before the Senate

Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity, said:

“In fact, there is no de facto segregation. All segregation re

flects some past actions of our governments.’’

10

forced in Virginia and denied enforcement in Ohio or

Indiana because of the vagaries of history.

Professor Bickel has commented on this double standard.

As he points out: “Outside the South . . . school segregation

is massive, and has, indeed, increased substantially in recent

years . . . caused mainly by residential patterns. Neverthe

less, very few federal courts have tried to intervene [and]

none has done so without qualification.”14

In commenting on the incongruity of different rules

issuing “out of the same federal judiciary” Professor Bickel

spoke of “one binding rule of constitutional law for Man-

hasset, New York” and “a different rule of constitutional

law for New York City.”15 16 *

Such a situation, without precedent in constitutional doc

trine, cannot be tolerated. Citizens are entitled to enforce

ment of constitutional rights evenly and consistently

throughout the United States. The Constitution requires

no less.18

B.

Racial Balance Is Not Required

Opponents of the school board plans insist upon sub

stantial racial balancing in each school in a system. If, as in

14 A. Bickel, The Supreme Court and the Idea of Progress 131

(1970). See also Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, supra, at 2-10.

15 Id. at p. 133. The Manhasset decision is found in Blocker v.

Board of Educ., 229 F. Supp. 709 (E.D.N.Y. 1964).

16 This is, among other things, the purpose of S. 4167, 91st

Cong., 2d Sess. (1970), introduced by Senator William B. Spong

of Virginia (and a similar bill introduced in the House of Repre

sentatives). Hearings on these bills have been held before ap

propriate committees in both houses. See also Sobeloff and Winter,

JJ-, concurring specially in Brewer v. School Bd., No. 14,544 (4th

Cir., June 22,1970) (Norfolk).

11

Richmond, the overall student population ratio is 60% black

and 40% white, these opponents contend that each school in

the system must have substantially this ratio both of pupils

and teachers.17

It is submitted that the racial balance concept is neither

required by the Constitution nor is in the public interest.

Indeed, if established as the “law of the land,” its conse

quences could be disastrous to public education.

The Decisions of This Court

What Brown I required, to assure equal educational op

portunity, was the elimination of racial segregation in the

schools. Subsequent cases have added the affirmative man

date that dual school systems must be eliminated and unitary

systems established.18 These are the terms with which local

school boards and lower courts have struggled. Some have

construed them to require racial balancing; others, more

perceptive we think, have recognized that this Court has

never projected a mechanistic solution for a problem of

such delicacy and diversity. Brown I states:

“. . . because of the wide applicability of this decision,

and because of the great variety of local conditions,

the formulating of decrees in these cases presents prob

lems of considerable complexity.” 347 U.S. at 495.

When the Court came to the problem of formulating de

crees, it provided substantial latitude:

17 Beckett v. School Bd., 308 F. Supp. 1274, 1276 (E.D.Va.

1969), stating the position of the plaintiffs. See Winter and Sobeloff,

JJ., concurring in part and dissenting in part, in the court below in

this case. „

18 Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ; Alexander v.

Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969); Carter v. West

Feliciana School Bd., 396 U.S. 290 (1970).

12

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power.” 349 U.S. at 300.

Further along in that opinion, Mr. Chief Justice Warren

recognized that there were a number of areas of considera

tion. He said:

“To that end, the courts may consider problems related

to administration, arising from the physical condition

of the school plant, the school transportation system,

personnel, revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of de

termining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the foregoing prob

lems.” 349 U.S. at 300-01.

The approach remains unchanged. In Green v. County

School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), Mr. Justice Brennan

said, speaking for the Court:

“There is no universal answer to complex problems

of desegregation; there is obviously no one plan that

will do the job in every case. The matter must be

assessed in the light of the circumstances present and

the options available in each instance.” 391 U.S. at 439.

See also United States v. Montgomery Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225, 235 (1969). And Mr. Chief Justice Burger

has made clear his view that there are a number of areas

other than (but including) transportation that must be

given consideration. He said, concurring in the result in

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) :

13

. . we ought to resolve some of the basic practical

problems when they are appropriately presented in

cluding whether, as a constitutional matter, any par

ticular racial balance must be achieved in the schools;

to what extent school districts and zones may or must

be altered as a constitutional matter; to what extent

transportation may or must be provided to achieve the

ends sought by prior holdings of the Court.” 397 U.S.

at 237.

This Court could hardly have more clearly stated its

refusal to enunciate a mechanistic rule of racial balance

in every case.

Racial Balance is Illusory

The issue before this Court is whether such a rule should

now be established. Those who support it argue that it has

the virtue of exactitude; that it would be easy for courts to

adopt and administer; and that it would put an end to the in

evitable litigation resulting from the application of a less

definitive rule.

We suggest that these views misconceive both the consti

tutional requirements and the realities of public education.

The racial mix varies widely among the cities and counties

of this country. The range is from school districts which

are perhaps 90% black (Washington, D. C. and Clarendon

County, South Carolina19) to many districts which are

nearly all white. The demography also constantly varies, es

pecially within cities. The population ratio changes as citi

zens move to suburban areas, and white and black families

19 See Brunson v. Board of Trustees, No. 14,571 (4th Cir., June 5,

1970).

14

are constantly moving within cities. Racial balance estab

lished one year would rarely be valid two or three years later.

The City of Richmond is not atypical. In 1960 the

school population ratio was 55% black and 45% white.

Prior to the annexation of a portion of Chesterfield County

on January 1, 1970, population shifts—some perhaps re

lated to integration, but most to the normal desire to live

in suburbia—had increased the ratio of black to 70%. An

nexation temporarily reversed this trend, so that the black

majority was reduced to about 60%. At the opening of the

present school session, it has grown to 64%. No one be

lieves it will remain there for as much as a year.

As shown in the Richmond case, population shifts within

the city have been equally dramatic. Many previously white

areas are now all black. But despite this shifting there are

in Richmond—as in scores of cities in the North and South

large areas populated entirely by blacks, with the fringes

populated by the poorer whites.20

To impose, as urged by plaintiffs, an arbitrary per

centage mixing in every school in Richmond would be as

unrealistic as to impose such a scheme upon New York,

Chicago, Philadelphia or Pittsburgh. Yet, if racial balance

is a constitutional imperative, it is applicable to all commu

nities at all times.

Racial Balance is Regressive

One wonders why compulsory racial balancing is ad

vocated. It would be difficult to conceive of a more certain

way to assure a return, in countless communities, to es

sentially separate schools—if not for whites and blacks,

certainly for those in the lower income levels of both races.

20 Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, supra, at 19-20, 31.

15

The shorthand term, often used critically, is “white

flight.” Concurring opinions below criticize this exercise of

freedom.21

But the connotation of “white flight” misconceives the

fundamentals. It is obviously true that since Brown the

white exodus to suburbia has accelerated. It must be re

membered, however, that the population movement from

congested urban areas into suburban environments has long

been characteristic of the American scene.22 It antedated

Brown; it exists throughout our country, and indeed abroad;

in its genesis, it bore no relation whatever to school integra

tion. Indeed, the desire to move upward economically and

socially—so basic to the American ideal—reflects itself no

where as strongly as in the urge for a better residential

environment. Often access to a particular neighborhood

school is a dominant factor in selecting a new home site.

These ambitions cannot be suppressed by court decrees.

The movement from congested urban areas will continue

regardless of how this case is decided. But few would doubt

that it will accelerate geometrically if the concept of racial

balance is enforced by law.23 Examples of the inevitable

21 See Sobeloflr and Winter, JJ., concurring in part and dissenting

in part in this case and in Brunson v. Board of Trustees, supra, at

n. 19. White flight is, of course, an erroneous term because middle

income citizens of both races are seeking suburbia.

22 United States Census of Population: 1960, Standard Metropolitan

Statistical Areas, Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce

1-257 (1963).

23 The trend toward private schools, especially in the South, will

also be accelerated. There are some who say that the “remedy” for

this is the outlawing of private schools or withdrawing of their tax ad

vantages. But this drastic solution would scarcely be acceptable to the

public generally. In addition, it would require the overruling of Pierce

v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 511 (1925).

16

resegregation24 process are numerous, but Washington,

D. C. suffices.

It is thus evident that enforced racial balance is both

regressive and unproductive. It frustrates the aspirations

of Brown, namely, the promotion of equal education oppor

tunity; it assures in time the resegregation of most of the

blacks in many urban communities. This will result in de

teriorating educational opportunities both for the poorer

blacks and whites who cannot afford to move.

In short, the end result is precisely the opposite of that

desired; it widens the disparities between the lower and the

middle-income families of both races.

The adverse economic and social consequences of re

segregation, however caused, also are disquieting. Prop

erty values deteriorate; sources of local taxation shrink; all

municipal services—as well as education—suffer; and—

worst of all—the quality of civic leadership erodes.25

The foregoing results, now known from experience to be

predictable, are scarcely in the public interest. They sug

gest the need for careful rethinking of proposals such as

enforced racial balance which accelerate the process of

urban deterioration.26

24“ [A]t the critical point—whatever it is—a formerly stable state

of integration tends to deteriorate, being reflected by the exodus of

white pupils. At the same time that this process is going on in the

schools, the exodus of white residents is also apparent in the turnover

of housing to the Negroes at only a slightly slower pace.” Civil Rights

U.S.A.: Public Schools North and West, U.S. Comm’n on Civil

Rights 185-86 (1962).

-5 Kerner et al., Report of the National Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders 220 (1968).

26 Indeed, the integration of schools is only one aspect of the com

plex of problems associated with urban life. The courts are ill-equipped

to deal with these problems, which lie primarily within the province of

the legislative and executive branches. The time may have come,

with respect to the schools, for greater reliance upon the Congress as

contemplated by Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

17

Restructuring of Governmental Relationships

The results of enforced racial balance could be sufficiently

serious to prompt demands for restructuring of federal and

state relationships. The facile answer to population with

drawal from urban areas is to enlarge the boundaries of

school districts.27 But this cannot be done, either by judicial

decree or federal legislation, without uprooting state consti

tutional and statutory provisions with respect to the auton

omy and authority of local school boards and governmental

subdivisions. And new and enlarged boundaries, wher

ever drawn, would not long contain a mobile and unwilling

population.

C.

The Highest Quality Of Education Must Be The Goal

If not racial balance, what is the alternative that is com

patible with the Constitution and the goal of quality educa

tion for all ? We think there can be no single, inflexible rule.

We start from principles settled by this Court: Racial dis

crimination is a denial of equal educational opportunity;

dual or segregated school systems are proscribed; and school

authorities have an affirmative duty to establish unitary sys

tems. These principles must be observed and applied, not as

ends in themselves but as means of achieving the educa

tional goal. The alternative then, to simplistic racial mixing

pursuant to formula, is to recognize that reasonable dis

cretion must be allowed in the assignment of pupils and the

administration of a school system so long as the foregoing

principles are not contravened and the measures taken com

port with the educational goal.

27 See Hobson v. Hanson, 269 F. Supp. 401, 515-16 (D.D.C. 1967),

aff’d sub nom., Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969).

18

That education of the best quality is the goal was clearly

recognized in Brown I :

“Today, education is perhaps the most important func

tion of state and local governments. Compulsory school

attendance laws and the great expenditures for educa

tion both demonstrate our recognition of the impor

tance of education to our democratic society. It is re

quired in the performance of our most basic public

responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is

the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a

principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural

values, in preparing him for later professional train

ing, and in helping him to adjust normally to his en

vironment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child

may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is

denied the opportunity of an education. . . . ” 347 U.S.

at 493.

It seems clear that desegregation by race is only one step

along the road toward equal educational opportunity—an

equal chance to obtain the best education that the particular

system can provide. The goal is the best education for all;

racial segregation is an impediment to be removed in striv

ing to achieve that goal.

The best education, however, is not achieved solely through

racial integration. In a recent article. Dr. David K. Cohen

states that “three major criteria of equality seem to com

pete as policy alternatives: equal resource allocation, de-

segregation, and equality of educational outcome. . . . ”

Cohen, Defining Racial Equality in Education, 16 U.C.L.A.

L. Rev. 255 (1969). But, as Dr. James Coleman, author of

the famous Coleman Report,28 has concluded, equal resource

allocation plus desegregation does not necessarily result in

improved educational output. He said that “ [t]he result of

28 Equality of Educational Opportunity, Office of Education, U.S.

Dept, of Health, Education and Welfare (1966).

19

the first two approaches (tangible input to the school, and

[de]segregation) can certainly be translated into policy,

but there is no good evidence that these policies will improve

education’s effects. . . Coleman, The Concept of Equality

of Educational Opportunity, 38 Harv. Educ. Rev. 7, 17

(1968). And the goal is, after all, the improvement of the

effect of education.

This conclusion has received the concurrence of Dr.

Cohen. He states:

“The problem, however, is that although desegrega

tion and equal resources are educationally salient, both

seem a good deal less strategic than achievement. Judg

ments about the quality of students’ education in

America are certainly not made on a purely merito

cratic basis, but students’ achievement still weighs more

heavily in the balance than either the degree of racial

integration, or the quality of resources in their schools.

The same thing is true of the standards presently em

ployed in assessing schools’ effectiveness. Equal

achievement seems the most relevant standard of racial

equality.” Cohen, Defining Racial Equality in Educa

tion, 16 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 255, 278 (1969).

Dr. Cohen concludes that the implicit assumption of

Brown I that desegregation and proper resource allocation

would result in equal achievement was an erroneous one:

“Experience and knowledge gained since then have

shown that the two standards cannot be met by the

same measures.” Id. at 280.

What, therefore, is the criterion? In Dr. Cohen’s words,

it is equal achievement; in Dr. Coleman’s, it is educational

output. What, in simpler terms, the school boards must seek

and the courts must approve is the means to promote equal

educational opportunity, regardness of race, in a system

structured for the highest achievement.

20

It seems strange that this goal is not mentioned by the

court below. It places no emphasis whatsoever on the

quality of education. It seems mesmerized by race; it hardly

seems to recognize that we are presented with an educa

tional problem of which race is merely a facet.29

D.

The Court Below Misapplied Its Rule Of Reason

The Court of Appeals in the Charlotte case adopted a

“test of reasonableness,” saying:

1. “not every school in a unitary school system need

be integrated.”

2. “school boards must use all reasonable means to

integrate the schools in their jurisdiction.”

3. Where all schools cannot reasonably be inte

grated, “school boards must take further steps to as

sure that pupils are not excluded from integrated

schools on the basis of race.”

These views, we think, are compatible with the opinions

of this Court. They do not accept the mechanistic rule of

racial balance.

But we believe the Court of Appeals misconceived the ap

plication of its own test. The focus, as is evident from the

rejection of the school board plans in Charlotte, Norfolk and

Richmond, was upon desegregation with little or no visible

concern for the object of desegregation, namely, improved

educational opportunity for all students. We think that the

Court below departed from an appropriate test of reason

ableness particularly with respect to (i) its emphasis on

29 The District Judge in the Norfolk case commented correctly that

the word “education” does not even appear in the opinion of the

Court of Appeals reversing his general approval of the Norfolk School

Board’s plan. Beckett v. School Bd., Civil Action No. 2214 (E.D.Va.,

Aug. 14, 1970).

21

extensive compulsory busing and (ii) its misappreciation

of the educational relevance of neighborhood or community

schools.

Compulsory Busing

There is nothing inherently wrong with transporting

school children where this is necessary. In every rural school

district busing is a necessity. In such districts in the South

it was used for decades to implement segregation. In the

Charlotte case, involving a large urban-rural school district,

there was substantial necessary busing before the District

Court undertook in effect to impose racial balance by ex

tensive cross busing.

Even in an urban district some busing may be appro

priate, contributing both to integration and sound educa

tion. The problem, one so familiar in law, is one of degree

and reasonableness. A notable example of unreasonable

busing in pursuit of racial balance is that ordered in Craw

ford v. Board of Education.30 In that case the Los Angeles

school board was ordered to establish a rigorously uniform

racial balance throughout its 711-square-mile district, with

its 775,000 children in 561 schools. This order, if upheld on

appeal, would require the busing of 240,000 students at a

cost of $40 million for the first year and $20 million for

each year thereafter with the result that the deficit of

$34-54 million already confronting the school board would

be increased by these amounts.31

30 No. 822, 854 (Cal. Super. Ct., Feb. 11,1970).

31 N.Y. Times, Feb. 12, 1970, at 1, col. 5 (city ed.). President

Nixon, in his statement of March 24, 1970, aptly states that rulings

of this character “. . . would divert such huge sums of money to

non-educational purposes, and would create such severe disruption

of public school systems, as to impair the primary function of provid

ing a good education.” Desegregation of America’s Elementary and

Secondary Schools, Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents

(March 30, 1970).

22

The preoccupation with “racial mixing of bodies”32 has

often caused the overlooking of the social and educational

disadvantages of busing, especially at the elementary level.33

It removes a child from a familiar environment and places

him in a strange one; it separates the child from parental

supervision for longer periods of time; it undermines the

neighborhood or community school, so desirable at the

elementary level; and it adds to already strained budgetary

demands.

These are the considerations which have prompted the

Congress, reflecting overwhelming public sentiment, three

times to record its opposition to enforced busing merely to

achieve racial balance.34 35 * *

The Neighborhood School

We think that the Court below also largely ignored the

educational advantages of the neighborhood school at the

elementary level. The geographic neighborhood is the most

common unit of organization of urban elementary public

schools.30 The neighborhood unit provides for ease of access

to schools for students, minimizing costs and time of

32 In his memorandum decision of August 14, 1970, attempting to

implement the mandate of the Circuit Court, Judge Hoffman com

mented “that the benefits of sound education have now been clearly

subordinated to the requirement that racial bodies be mixed.”

See also Beckett v. School Bd., 308 F. Supp. at 1302.

33 A disturbing aspect of seeking racial balance at any cost is that

children too often are treated as pawns to produce sociological changes

that are related more to other factors, such as housing, than to edu

cation.

34 Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c(b) (1964) ; Ele

mentary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, 20 U.S.C. § 884

(1966), amending 20 U.S.C. § 884 (1965) ; Education Appropriations

Act of 1971, P.L. 91-380, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., §§ 209, 210 (1970).

35 New York City’s current experiment in decentralization is

further evidence of the vitality of the neighborhood or community

concept. N.Y. Times, Sept. 13, 1970, at 1, col. 2.

23

travel to and from school, and thus maximizing the po

tential extracurricular role schools can play in the lives

both of parents and children. These factors, along with

the associational benefits of attending school with friends

which, particularly for elementary school children, ease

the psychological stress of initial adjustment to school,

have led such a noted educator as James B. Conant, former

President of Harvard University, to the conclusion that

“ [a]t the elementary school level the issue seems clear. To

send young children day after day to distant schools seems

out of the question.”36

The quality of a community’s education depends ulti

mately upon the level of public suport.37 A willingness to

pay increased taxes and to vote for bond issues can evapo

rate quickly in the face of enforced busing and dismantling

of neighborhood schools where such actions do not con

tribute to improved education for all.

Educational effectiveness also is dependent on the attitude

of parents toward their children’s education, and rationally

configured systems of neighborhood schools play a vital

role. Parental support of their children’s schooling normally

reinforces the efforts of their children’s teachers in sub

stantial measure;38 to the degree that schools can involve

parents with their children’s education as such,39 or broaden

the parents’ own educational horizons,40 this end is served.

Community schools, when designed in such a way as to

avoid the feelings of disaffection which attend systematic

38 J. Conant, Slums and Suburbs 29 ( 1961).

37 A current dramatic example of the financial crisis in public edu

cation across the country is found in St. Louis, Missouri, where tax

payers in four suburban school districts north of the city have shut

46,(XX) pupils out of classes by consistently defeating school tax levies.

N.Y. Times, Sept. 14, 1970, at 1, col. 3.

38 M. Weinberg, Desegregation Research: An Analysis 140-41

(1968).

39 Christian Science Monitor, Aug. 14, 1970, at 11, col. 1.

40 C. Hansen, Danger in Washington 81 (1968).

24

ghettoization, whatever its origin, foster such an active

parental role because of their very accessibility.

Further, the accessibility of community schools mini

mizes the cost of school transportation for students. Pro

vision of substantial transportation at public cost solely for

the purpose of attaining racial balance diverts resources

which might otherwise be used, in a neighborhood scheme

consistent with students’ constitutional rights, for more

directly constructive educational purposes. Where the cost

of such transportation is borne privately by the families of

students—assuming that public transportation facilities are

adequate to cover the necessary specialized routes—it strikes

regressively, imposing a heavier burden on the poor than

on the affluent.

This Court in Brown II, in suggesting “revision of school

districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a system of determining admission to the public schools on a

non-racial basis”41 as a means of complying with the equal-

educational-opportunity requirement of Brown I, implicitly

recognized the advantages of the community school sys

tem.42

The unique educational advantages of the neighborhood

school system, where it is administered in a manner con

sistent with the Equal Protection Clause, result in the

accomplishment of the ultimate goal of that clause: the

best possible education for all children. Pursuit of absolute

racial balance in major metropolitan areas through the use

of extensive busing of students deprives the school system

of the singular advantages of the neighborhood concept,

and in at least this respect thwarts the attainment of equal

educational opportunity.

« 349U.S. at 300-01.

42 These advantages were well expressed in Deal v. Cincinnati Bd.

of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied 359 U.S 847

(1967).

25

It has frequently been pointed out that neighborhood

school systems have, on occasion, come into existence for

the purpose of fostering racial segregation.43 But this fact

should no more prejudice consideration of the intrinsic edu

cational merits of a racially satisfactory neighborhood

school system than should these merits justify it when it is

administered in a fashion which entrenches unconstitutional

racial imbalance.

Other Considerations

The community school concept is capable of flexible

administration: zoning, pairing, clustering, and siting of

school buildings all are techniques which may be used, con

sistent with its advantages, and should be, when reasonable,

to fulfill constitutional requirements. In addition, a majority-

to-minority transfer option and specialized learning centers

may be provided to ameliorate the effect of residential segre

gation. Techniques which destroy the advantages of the

community school in pursuit only of mechanistic racial bal

ance in the name of the Fourteenth Amendment tend to

negate the very educational values in whose service they

are invoked.

But these are measures that are customarily used in the

racial desegregation context; they are by no means all of the

factors to be taken into account in devising a plan designed

to promote educational achievement for all students to the

utmost.

Modern social scientists have developed studies that take

into account a number of other factors. These include a de

termination of the racial mix that will maximize educa

tional achievement, development of plans that maximize

use of physical facilities, teachers and staff, avoidance of

43 See, e.g., Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, U.S. Comm’n

on Civil Rights 252 (1967).

26

resegregation and “white flight,” consideration of the de

sirable socio-economic mix, preservation of the cultural

uniqueness and autonomy of the individual student, giving

effect to positive and realistic educational and vocational

aspirations and other relevant factors of equal importance.44

Such evidence is sound and available.45 Plans based on

such studies will result in greater educational achieve

ment. Education is not based on race alone. That plan is

the best plan that provides the best opportunity for educa

tional achievement for all students. In the preparation of

such a plan, racial imbalance is a consideration, but it is

not the controlling factor.

It is in this light, we conceive, that the rule of reason

postulated by the court below should be applied. The rule

of reason makes little sense when it is couched in purely

racial terms. The creation of racial balance by massive

busing may eliminate racial segregation, but it may harm

the general level of educational achievement. What schools

need desperately is to improve that level. This Court should

provide a more realistic approach to achieve that end.

VI.

CONCLUSION

The Court has the opportunity in this case to resolve the

principal issues which have confused and divided the lower

44 See, e.g., M. Weinberg, Desegregation Research: An Analysis,

supra; Equality of Educational Opportunity, supra.

45 Evidence of this nature was presented in the Norfolk case by

Dr. Thomas F. Pettigrew and disregarded without mention by the

Circuit Court. But Dr. Pettigrew’s evidence in the Norfolk case is

substantially the entire basis for the opinion of three of the judges in

the Clarendon case. See Craven, J., concurring and dissenting in

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, No. 14,571 (4th Cir., June 5, 1970).

If testimony of this character may be used as a basis for decision in

one case, it clearly deserves consideration in another.

27

courts and school authorities. We respectfully suggest, for

the reasons that we have stated, the following:

(i) The purported distinction between de jure and de

facto racial segregation should be rejected. It can be sup

ported neither factually nor consistently with constitutional

principles. The right to equal educational opportunity must

be uniform throughout the United States.

(ii) The concept of racial balance is not a constitutional

imperative. If pursued as an end in itself, rather than as a

factor to be considered, this concept accelerates the process

of resegregation and frustrates the attainment of sound

educational goals.

(iii) The Constitution does not delineate the extent to

which the transportation of pupils may or must be provided

to achieve and maintain a unitary school system. Nor does

the Constitution prescribe the extent to which school at

tendance zones may or must be altered for this purpose.

(iv) The principles settled by this Court must be ob

served : racial discrimination is a denial of equal educational

opportunity; dual or segregated school systems are pro

scribed; and school authorities have an affirmative duty to

maintain unitary systems. But these principles must be ap

plied as the means of maximizing the educational oppor

tunity for all students. A reasonable discretion must be

allowed school authorities in assigning pupils and adminis

tering a school system so long as these principles are not

contravened and the measures taken comport with the edu

cational goal.

(v) School authorities should give appropriate weight

to the educational advantages of the neighborhood or com

munity schools and the disadvantages of extensive cross

busing in urban areas, especially for young children.

28

(vi) In devising plans to assure a unitary school system,

all relevant techniques may be considered, including the re

alignment of attendance zones, the flexible utilization of

school facilities, and the assurance of opportunities for

interracial learning experience.

(vii) Perhaps the overriding need is to shift the empha

sis from a mechanistic approach of integration as an end

in itself to the goal desired by every citizen: Equal educa

tional opportunity in a school system structured for the

highest achievement by all students.

It is not too much to say that public education is in a

state of serious disarray, with increasing evidence of erod

ing public support. The problems and confusion relating

to integration are a contributing though not the only cause.

The time has come for a clarification of the principles to be

applied by the courts. We respectfully submit that those

outlined above are consistent both with constitutional re

quirements and the urgent need for improved education.

Dated September 16, 1970

Respectfully submitted,

A n d rew P . M iller

Attorney General of Virginia

W il l ia m G. B roaddus

T heodore J . M arkow

Assistant Attorneys General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

L e w is F. P ow ell , J r .

J o h n W . R iely

G eorge H . H ett r ic k

G uy K . T ow er

H u n t o n , W il l ia m s , Gay ,

P o w ell & G ibson

Of Counsel

Special Counsel

700 East Main Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219