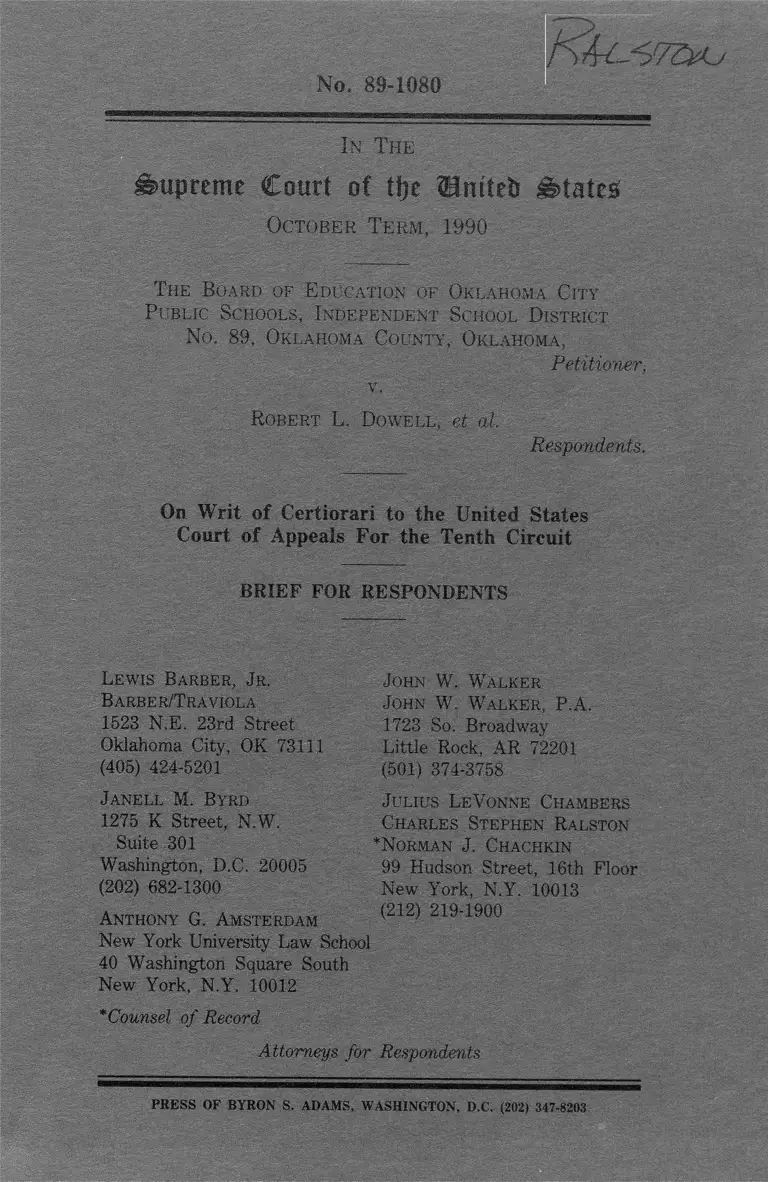

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief for Respondents, 1990. 26574827-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76e12011-afb2-4ed0-b1b7-b4eaae280d97/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No, 89-1080

TZMj

In The.

Supreme Court oC ttje Hmtets States

October Term, 1990

The Board of Education of OklafjSma City

P ublic Schools, Independent School District

No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma,

Petitioner,

m

Robert L. Dowell, et at,

Respondents.

On W rit of C ertiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals For the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Lewis Barber, Jr.

Barber/Traviola

1523 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

Janell M. Byrd

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Anthony G. Amsterdam

New York University Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, N.Y. 10012

John W. Walker

John W. Walker, P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

*Norman J. Chachkin

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Respondents

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

1

Counter-Statement of

Question Presented for Review

A single question arises on the facts of this case:

May a school district that obeys a federal court order

requiring it to implement a new student assignment plan to

accomplish desegregation, consistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment and equitable principles, dismantle that plan,

and thereby re-create the all-Afro-American schools whose

elimination was the purpose of the court order, when the

uncontroverted evidence demonstrates that the conditions that

made the order necessary (racial residential segregation that

the court determined to have resulted from official state

action including action of the school authorities) yet persist?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Counter-Statement of Question Presented for Review . . . i

Table of Authorities..................................................................... iii

OPINIONS B E L O W ............................. 1

ST A TEM EN T........................................................................... 2

A. Early Stages of the L itig a tio n ........................... 2

B. The 1972 Desegregation Order ........................ 5

C. The 1977 "Unitary" O rd e r ................................. 7

D. The Dismantling of Elementary School

Desegregation ............................................. 10

E. The Plaintiffs’ Motion to Reopen the Case . 18

F. The District Court’s O rd e r ............ .................. 24

SUMMARY OF A R G U M EN T.......................................... 26

ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 30

In troduction ............................................................... 30

I. SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASES ARE

GOVERNED BY THE EQUITABLE

PRINCIPLES ESTABLISHED BY UNITED

STATES v. SWIFT & CO............................. 33

A. United States v. Swift & Co. Governs

This Case................ ........................... 33

B. The School Board Has Failed to

Justify Resegregating Schools Under

Even a Lesser Standard than Swift. 41

ii

Page

II. ALTERNATIVELY, A FINDING OF

UNITARINESS MAY TERMINATE THE

OBLIGATION TO ADJUST PUPIL

ASSIGNMENT PLANS TO ACCOUNT

FOR DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS ............ 49

III. ALTERNATIVELY, A SYSTEM CAN BE

"UNITARY" ONLY UPON A FINDING

THAT IT WILL REMAIN SO IN THE

FACE OF ANY CHANGES IN PUPIL

ASSIGNMENT PO LIC IES........................ 54

C O N C L U S IO N ..................................................................... 59

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 2,

30, 32

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) . . 3,

30, 32

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1 9 1 7 ) ........................ 20

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 219 F. Supp. 427

(W.D. Okla. 1963) .................................................................3

iii

Page

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971

(W.D. Okla. 1965), a ff’d, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967).......................................... 3, 5

IV

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 338 F. Supp. 1256

(W.D. Okla.), a ff’d, 465 F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert,

denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1 9 7 2 ) ........................ 6, 8, 16, 53

Dowell v. School Bd. of Education of Oklahoma City, 677

F. Supp. 1503 (W.D. Okla. 1987) ........................ 16, 18,

24, 25, 32, 37, 41, 53

Dowell v. School Bd. of Education of Oklahoma City, 890

F.2d 1483 (10th Cir. 1989)................................. 25, 51, 52

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) ............................................. 32, 45, 53, 56, 57

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1 9 7 7 )..................... 56

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976) ................................................ 27, 28, 30, 35, 50, 51

Page

Pennsylvania v. Wheeling & B. Bridge Co., 59 U.S. 421

(1856) ............................................................... .. .................. 39

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................... 3

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Ed., 611 F.2d 1239 (9th

Cir. 1979)............................................................................. 40

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971) .................. 27, 31, 32, 35, 42, 45, 46, 50, 51, 56

System Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642

(1961) ........................................................................... 35, 39

V

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971) 35

Page

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Ed., 407 U.S.

484 (1972) ............................................................ 46, 53, 54

United States v. Swift & Co., 189 F. Supp. 885 (D.C. 111.

1960), a ff’d per curiam, 367 U.S. 909 (1961) ............ 35

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932) . 26,

27, 33, 35, 36, 39, 41, 48

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S.

244 (1968) 35

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ............................................................... 40, 46, 53, 54

Statutes:

Lord Bacon’s Ordinances (1618) .......................................33

Rule 60(b), F. R. Civ. Proc...................................................37

Other Authorities:

Bacon, Works (Spedding ed. 1 8 7 9 ) ................................... 34

Developments in the Law, Injunctions, 78 Harv. L. Rev.

994 (1965) 34

Moore, Moore’s Federal Practice f 60.26[4] 35

VI

Page

Note, Finality o f Equity Decrees in the Light o f Subsequent

Events, 59 Harv. L. Rev. 957 (1946) ........................... 34

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure, § 2961

(1973) .................................................................................... 33

No. 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

The Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, Independent School D istrict

N o. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma,

v.

Petitioner,

Robert L. D owell, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals For the Tenth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

OPINIONS BELOW

In addition to the opinions listed by Petitioner, the

following opinions of the United States District Court for the

2

Western District of Oklahoma and the Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit are relevant to the decision of this case.

219 F. Supp. 427 (1963); 244 F. Supp. 971 (1965); 307 F.

Supp. 583 (1970); 338 F. Supp. 1256 (1972); 606 F. Supp.

1548 (1985)(J.A. 177-196); 375 F.2d 158, cert, denied, 387

U.S. 931 (1967); 465 F.2d 1012, cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1041 (1972); 795 F.2d 1516, cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938

(1986)(J.A. 197-214).

STATEMENT

A. Early Stages of the Litigation

This action was brought in 1961 by Afro-American

children and their parents to end the de jure segregation of

the public schools in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Prior to

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)(Brown

I) separate schools for Afro-American and white students

had been required by the constitution of Oklahoma since its

3

admission into the Union as a "Jim Crow State" in 1907.

Dowell v. School Bd. o f Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219

F. Supp. 427, 431 (W.D. Okla. 1963).1

Shortly after Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S.

294 (1955)(Brown II), the Oklahoma City School Board

adopted, for the first time, a plan of neighborhood schools,

ostensibly to end segregation. However, all the plan did

was to impose local attendance zones on housing that was

rigidly segregated by race. The pattern of residential

segregation had been created by statute, through the

enforcement of restrictive covenants until the decision in

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948),2 and by other

practices of the state, city, and school district. As the

district court found:

1 Racially separate schools had evidently been in place before

statehood as well. 219 F. Supp. at 434, quoting the Oklahoma City

School Board’s 1955 "Statement Concerning Integration."

2 See Dowell v. School Bd. o f Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971, 975

(W.D. Okla. 1965).

4

The residential pattern of the white and

Negro people in the Oklahoma City school district

has been set by law for a period in excess of fifty

years, and residential pattern has much to do with

the segregation of the races. . . . Thus the schools

for Negroes have been centrally located in the

Negro section of Oklahoma City, comprising

generally the central east section of the City. . . .

The patrons of the School district had lived under

a dual school system and the children’s residential

areas were fixed by custom, tradition, restrictive

covenants and laws.

219 F. Supp. at 433-434. Indeed, the establishment of

neighborhood schools intensified patterns of residential

segregation, with white families moving out of the east

central area of the city where Afro-Americans were

concentrated, and Afro-Americans moving in. Moreover,

even those white families who remained in the Afro-

American ghetto were allowed to transfer their children from

their school attendance areas to areas where whites

predominated in the schools. In light of these facts, the

court concluded that the defendants had not made a good

faith effort to integrate the schools. Id. at 434-35.

5

Two years later, the district court again found the

school district’s proposed integration plan wholly inadequate

because it adhered to a neighborhood school policy, and:

. . . such a policy when superimposed over already

existing residential segregation initiated by law in

Oklahoma City, leads inexorably to continued

segregation. . . . [Inflexible adherence to the

neighborhood school policy in making initial

assignments serves to maintain and extend school

segregation by extending areas of all Negro

housing, destroying in the process already

integrated neighborhoods and thereby increasing the

number of segregated schools.

Dowell v. School Bd. o f Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971,

976-77 (W.D. Okla. 1965), ajf’d, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.),

cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967).

B. The 1972 Desegregation Order

In 1972 the district court held that the desegregation

plan put into effect by the school district in 1970 had been

ineffective and that the school board had "totally defaulted

in its acknowledged duty to come forward with an acceptable

6

plan of its own." Dowell v. School Bd. o f Oklahoma City,

338 F. Supp. 1256, 1271 (W.D. Okla.), ajf’d, 465 F.2d

1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972).

Indeed, the plan was not "the plan approved by [the] court"

since "the Defendant School Board, without notice to or

permission to the court, [had] proceeded to emasculate the

plan." Id. at 1262, 1263. With regard to elementary

schools in particular, the school board’s plan resulted in 69

of 86 schools remaining 90% or more predominantly white

or Afro-American. Id. at 1260. Sixteen of those schools

were virtually all-Black, with white enrollments from 0 to

1.7%. Again, the vice of the school board’s approach was

that it imposed a neighborhood school plan on segregated

residential patterns.

Finding that the school board’s plan "will not work" to

desegregate the schools and eliminate the vestiges of

segregation, the district court adopted the plaintiffs’ plan

7

(The Finger Plan) and held that it "would, if adopted and

implemented in good faith, create a unitary system," Id. at

1269, 1271. The Finger Plan utilized a variety of methods,

including grade restructuring and school clustering,

transportation, restructuring of school boundaries, and feeder

schools to integrate fully the elementary, junior high, and

high schools. The district court’s order was affirmed on

appeal, and the Finger Plan was implemented in the Fall of

1972.

C. The 1977 "Unitary" Order

The Finger Plan desegregated the schools of Oklahoma

City at all levels. In its 1972 order, the district court

required that:

The Defendant School Board shall not alter or

deviate from the [Finger Plan] . . . without the

prior approval and permission of the court. If the

Defendant is uncertain concerning the meaning of

the plan, it should apply to the court for

interpretation and clarification.

8

338 F.Supp. at 1273. This order was not vacated until

1987. In 1975, the Board of Education filed a motion

requesting dismissal of the lawsuit on the ground that the

School District had complied with the 1972 order. At a

hearing held on November 18, 1975, the then president of

the school board testified that the board did not seek

dismissal of the case in order to return to segregated

schools.

[THE COURT:] The Court would like to ask you,

if the Court should terminate its jurisdiction, will

this mean that the Board will terminate its busing

program for desegregation?

THE WITNESS: No, sir.

THE COURT: Would it mean that you would lessen

your busing program to any degree?

THE WITNESS: No, sir.

THE COURT: Do you know of any other way in

which you can bring about desegregation except through

busing?

THE WITNESS: I think that it’s certainly going to

require transportation of some sort, busing of some

9

nature.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit ("PX") 55 (Transcript of hearing of

November 18, 1975, p. 69) (J.A. 103-04).

Subsequently, on January 18, 1977, the district court

entered an "Order Terminating Case" that recited that the

Finger Plan:

worked and that substantial compliance with the

constitutional requirements has been achieved. The

School Board, under the oversight of the Court, has

operated the Plan properly, and the Court does not

foresee that the termination o f its jurisdiction will

result in the dismantlement o f the Plan or any

affirmative action by the defendant to undermine

the unitary system so slowly and painfully

accomplished over the 16 years during which the

cause has been pending before the Court.

. . . The Court believes that the present members

and their successors on the Board will now and in

the future continue to follow the constitutional

desegregation requirements. (Emphasis added.)

(J.A. 174-75.)

Although the case was dismissed, the permanent

injunction was not dissolved. For eight more years the

10

expectation of the court and of plaintiffs was fulfilled, and

the school district continued to operate a desegregated school

system under the Finger Plan until the 1985-86 school year.

D. The Dismantling of Elementary School Desegregation

Over the course of implementing the Finger Plan, the

greatest part of the burden of busing for integration of the

elementary schools fell on Afro-American students. Under

the plan, formerly Afro-American schools became fifth-year

centers serving only the fifth grade and kindergarten. As a

result, Afro-American elementary-grade children living in

the northeast quadrant and other predominantly black areas

of Oklahoma City were transported four out of five years,

while white students were bused only in the fifth grade.

Witnesses for both plaintiffs and defendants agreed that this

was inequitable. Transcript of Hearing, June 15-24, 1987

("Tr."), PP- 220; 292; 385; 432-33; 512; 642; 1265; 1412-

11

13; 1431-33 (J.A. 283-83; 303-04; 330; 341-42; 347; 384;

501; 516-18; 521-23.)

The inequity resulted in part from the failure of the

school board to change student assignments to add grades to

schools in the northeast quadrant, although this was

suggested by the school system’s research staff. Tr. 498-

99 (J.A. 345-46). The school district’s own expert witness

testified that in light of the demographic change, the addition

of grades would have been essential to maintain integration

with a minimum amount of busing. Tr. 292-93 (J.A. 303-

04).

Another source of inequity was the "stand-alone" school

feature of the Finger Plan and the manner in which it was

administered by the school district. Under the plan, any

elementary school within a grade-restructured cluster that

could itself be desegregated, by establishing a contiguous

geographic attendance zone around the school that would

12

result in a student body more than 10% but less than 35%

Afro-American, would be withdrawn from a grade-

restructured cluster of schools, and would operate as a

school enrolling grades K-5.3 Because of demographic

patterns, the creation of "stand-alone" schools in certain

areas could lead to the closing of schools in the northeast

quadrant, where the Afro-American population was

concentrated, and to increased busing of students living in

that quadrant.4

3 Under the Finger Plan the clustered schools were divided into ones

that served Kindergarten and grade 5, and ones that served grades 1-4.

All Kindergarten children went to schools in their own neighborhoods,

Afro-American children were bused when they were in grades 1-4, and

white children were bused when they were in grade 5. A "stand-alone"

school served all children in grades K-5 who lived in a contiguous

geographic attendance zone that produced a desegregated student body.

4 White students in grade 5 were bused into schools in the Afro-

American neighborhood. Therefore, the creation of "stand-alone

schools in predominantly white neighborhoods reduced the number of

fifth graders available for transportation, and therefore reduced the total

student body of schools m Afro-American areas. Once the student body

fell below to a certain level, a school was closed. At the same time,

the conversion of a school that was near an Afro-American neighborhood

to "stand-alone" status meant that Afro-American students in grades 1-

4 would have to be bused longer distances to another clustered school.

13

In 1984, the school board decided to establish the

Bodine Elementary School as a K-5 "stand-alone" school.

Defendant’s Exhibit ("DX") 76 (J.A. 586 ). Dr. Clyde

Muse, an Afro-American school board member, expressed

concern about the increase of the already inequitable busing

burden on Afro-American students from the northeast

quadrant. The school board established a committee to

examine the question, and in its report of November 19,

1984, the committee recommended that K-4 neighborhood

schools be established throughout the district. PX 9.

The committee and the school board were fully aware

that the elimination of the Finger Plan’s clustering approach

for the elementary schools would result in reestablishing

elementary schools that had heavily Afro-American or non-

Afro-American student enrollments.5 Nevertheless, on

December 17, 1984, and without notification to or approval

5 DX 79, p. M-3 (Minutes of Board of Education meeting,

November 19, 1984)(J.A. 602-08).

14

by the district court as required by the outstanding

permanent injunction, the Board of Education approved the

plan, dismantling the Finger Plan’s clustering approach and

substituting geographically zoned "neighborhood" schools

serving grades K-4. Although some portion of the Afro-

American community supported the abandonment of

clustered schools, their support was based on the reduction

of the inequitable busing burden on Afro-American children

and the retention of elementary schools in the northeast

quadrant. Tr. 642 (J.A. 384). However, other Afro-

American parents objected to the new plan because it would

result in re-segregating the district’s elementary schools. PX

56, M-5; Tr. 512; 1412-13; 1431-33 (J.A. 552-60; 347;

517-18; 521-23).

The plan adopted in 1985 remains in effect today. The

elementary school zones established by the 1985 plan are the

same as those used in 1971 and earlier, except for

15

modifications necessitated over the years because of school

closings. As the following table demonstrates, ten schools

that were segregated in 1971, but that were desegregated

from 1972 until 1984-85 by the Finger Plan, were

resegregated in 1985 by the unilateral abandonment of the

Finger Plan and the re-imposition of neighborhood zones on

segregated housing.

16

School % Afro-American Enrollment

1971-72* 1984-856 7 1985-861

Creston Hills 100.0 41.4 99.0

Dewey 99.2 33.5 96.6

Edwards 99.7 29.7 99.5

Garden Oaks 100.0 36.9 99.0

King (formerly Harmony) 99.7 43.2 99.7

Lincoln 99.1 36.9 97.2

Longfellow 99.3 32.2 99.6

Parker 99.7 72.3 97.3

Polk 97.8 31.6 98.4

Truman 100.0 27.6 98.7

6 Source: 338 F. Supp. at 1260.

7 Source: PX 50 (J.A. 543-45).

Source: 677 F. Supp. at 1510.

17

All of the above schools except Parker are located in the

northeast quadrant. Moreover, in 1971 the attendance zones

of Creston Hills, Dewey, Dunbar, Edison, Edwards, Garden

Oaks, Lincoln, Longfellow, Page, and Woodson defined the

outer boundaries of the northeast quadrant. In 1985-86 the

same geographic area was defined by the attendance zones

of Creston Hills, Dewey, Edwards, Garden Oaks, Lincoln,

and Longfellow. Thus, when allowances are made for the

closing of some schools, the elementary school zones under

the plan adopted in 1985 are operationally the same as those

used before 1972. As described above, it was the

segregative effect of neighborhood zones on this very area

that was the basis for rejecting neighborhood schools in

1972.

The immediate consequence of the new plan was that,

in the school year 1985-86, 40% of the Afro-American

children in grades 1-4 attended these ten virtually all-black

18

schools. Overall, 44.7% of the district’s Afro-American

pupils in those grades attended schools with enrollments

greater than 90% Afro-American,9 in a school system in

which 36% of the elementary school children are Afro-

American.10

E. The Plaintiffs’ Motion to Reopen the Case

On February 19, 1985, immediately after the adoption

of the neighborhood school plan, plaintiffs (respondents here)

moved to reopen the case to challenge the plan’s validity.

After a hearing, the motion was denied on the ground that

"once a school system has become unitary, the task of a

supervising federal court is concluded." 606 F. Supp. 1548,

1555-56 (W.D. Okla. 1985)(J.A. 192). The Tenth Circuit

reversed and remanded the matter with instructions for the

9 PX 26, 27.

10 677 F. Supp. at 1510.

19

district court to determine whether "changed conditions

require modification or [whether] the facts or law no longer

require the enforcement of the [1972 injunctive] order." 795

F.2d 1516, 1523 (10th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 479 U.S.

938 (1986)(J.A. 213).

On remand from the court of appeals the district court

granted the motion to reopen and held a hearing from June

15 through June 24, 1987. At the hearing the school board

had the burden of demonstrating sufficiently changed

conditions to justify the dissolution of the permanent

injunction. An issue central to the district court’s decision

was whether the continuing residential segregation, and

particularly the virtually all-Afro-American northeast

quadrant in which the elementary schools in question were

still located, continued to be the result of the prior actions of

various governmental agencies, including the school board.

In other words, the issue was whether the effects of the prior

20

unlawful discrimination and segregation had become so

attenuated as to no longer contribute to the still-existing

housing segregation.

Petitioner’s chief witness with regard to this issue was

William Arthur Valentine Clark, a professor of geography at

the University of California at Los Angeles. Dr. Clark was

qualified as an expert in population geography and

demography and testified as to population movements in

Oklahoma City. He first testified that the original

concentration of Afro-Americans in certain sections of the

city was due in substantial part to city ordinances that

restricted the areas in which they could live.11 However, he

said that beginning in 1968 and continuing into the 1970’s

the passage of fair housing laws at the federal, state, and

local levels removed the legal barriers to Afro-Americans

11 Professor Clark testified that such ordinances were in force as late

as the 1930’s. Tr. 46 (J.A. 236). Of course, this Court had held that

such laws were unconstitutional in 1917. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S.

60 (1917).

21

living in other parts of the city, with the result that by the

early 1980’s there had been a dispersal of Afro-American

families into previously all-white areas. However, the East

inner part of city remained virtually all-Afro-American,

although a smaller proportion of the total Afro-American

population resided there than previously.12

On direct examination Dr. Clark expressed the opinion

that the all-Afro-American tracts in the East inner section

were not a vestige of state actions of 30 to 40 years ago.

However, on cross-examination Dr. Clark reiterated his

testimony that whites would not move into areas where the

Afro-American population was above 20-25%; indeed,

whites tend to move out of neighborhoods that reach around

30% Afro-American.13 Therefore, it was Dr. Clark’s

opinion that whites would not be expected to move into the

Tr. p. 67 (J.A. 246).

Id., at 105 (J.A. 257-58).13

22

established Afro-American residential areas and,

consequently, into the newly established school attendance

zones.14 Thus, the past official segregatory actions resulted

in Afro-American neighborhoods into which whites would

not move.

Q. And does it not therefore follow that, to the

extent that past discrimination was a factor in

establishing concentrated minority residential areas,

that those areas are unlikely to change because of

the antipathy of whites to moving in unless and

until their black residents move somewhere else?

A. I think that you would have to agree with that,

given what I ’ve testified. Yes.

* * *

Q. . . . [A]s long as school attendance is

determined by residential zones, such as those

which have been drawn which overlay areas of

established black concentration, you wouldn’t

anticipate white families moving into those areas?

A. I would not anticipate white families moving

in. N o.15

14 Id. at 106 (J.A. 258).

Id., at 106-107 (J.A. 258-60).15

23

The testimony of one of respondents’ witnesses,

Professor Maxy Lee Taylor, fully corroborated this

conclusion of Dr. Clark. Dr. Taylor noted that while Afro-

Americans had moved into formerly all-white areas, the

reciprocal change had not occurred. The reason was that

"white residents are not going to move into historically black

areas."16 This is particularly true where white aversion to

moving into a heavily Afro-American neighborhood is tied

to a history of official discrimination and segregation,

including the maintenance of segregated schools.

A. Yes, I think there’s a lot of evidence that white

attitudes about desegregation are, in fact, shaped by

the history of segregation that those whites have

been exposed to. . . . [I]n places like Oklahoma

City, where the black neighborhood was created by

state action, the involvement of public officials, the

fait accompli phenomenon implies that white

avoidance of desegregation would be particularly

great for that reason. In other words, the official

segregation encourages attitudes that . . .

segregation is appropriate, justified, that it . . .

would be undesirable for whites to live in

Id., at 1231 (J.A. 490-91).16

24

predominantly black neighborhoods.17

Respondents also put on the testimony of Gordon

Foster, an expert in the areas of school administration and

school desegregation planning and implementation. Dr.

Foster presented an alternative desegregation plan that would

modify the Finger Plan to alleviate the inequitable burdens

on Afro-American school children and the Afro-American

community while maintaining a fully desegregated system.18

F. The District Court’s Order

On December 9, 1987, the district court issued its

opinion and order dissolving the 1972 decree and

relinquishing any further jurisdiction. 677 F. Supp. 1503

(W.D. Okla. 1987). With regard to the question of

residential segregation, the court acknowledged the evidence

17 Id. , at 1231-1232; see also id., at 1234-37 (J.A. 490-95).

18 Id. , at 1278-1282 (J.A. 506-10).

25

that few if any white families would chose to move into the

predominantly Afro-American inner city area, but did not

mention Dr. Clark’s testimony that this reluctance was

linked to the creation of the ghetto by official action.19 The

court concluded that the school district had achieved

"unitary" status and that therefore the 1972 decree should be

dissolved.

The court of appeals reversed primarily on the ground

that the petitioner had not made a sufficient showing of

changed circumstances that would justify the dissolution of

the injunction. The reversion of ten schools to the same

total segregation that existed prior to the decree being

implemented was inconsistent with a demonstration that "‘the

dangers the decree was meant to foreclose must almost have

disappeared.’" 890 F .2d 1483, 1493 (10th Cir. 1989). The

decision of the district court was reversed and the case

677 F. Supp. at 1512.19

26

remanded for further proceedings. The petitioner sought

review from this Court, and certiorari was granted on

March, 26, 1990.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

A. School desegregation cases, as cases in equity, are

governed by the same principles regarding dissolution or

modification of permanent injunctions as are all other cases

in equity. Since an injunction is directed to the future, a

court in equity retains the inherent power to modify it to

adapt to changed conditions. However, that power is

governed by the principles enunciated in United States v.

Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932). Thus, a permanent

injunction will not be revoked or modified unless changed

circumstances have turned it into "an instrument of wrong."

Id., at 115. The mere fact that petitioner would prefer, or

27

would be better off, if the injunction were relaxed is not

sufficient; there must be a "clear showing of grievous wrong

evoked by new and unforseen conditions." Id., at 119. No

such showing has been made here. The decisions of this

Court have made it clear that school desegregation cases are

governed by generally applicable equitable principles (Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., 402 U.S. 1 (1971)),

including the rule of United States v. Swift & Co. (Pasadena

City Bd. ofEduc. v. Spangler, A l l U.S. 424, 437 (1976)).

B. Even under a standard less exacting than that of

Swift, petitioner has not shown sufficient justification for

relief from the injunction. The reconsignment of 40% of the

school system’s Afro-American elementary school children

to virtually all Afro-American schools is inconsistent with

the principles enunciated in Swann. The reimposition of

neighborhood schools on racially segregated housing caused

by state action, including acts of the school district, has

28

resulted in a school system in which the vestiges of the prior

segregated system manifestly have not been eliminated "root

and branch"

II.

This case does not present the situation that existed in

Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, where a school

system was required to readjust school boundary lines

periodically in order to maintain "racial balance" in schools

in the face of demographic changes in the community. To

the contrary, here it was petitioner school board that

unilaterally, without notice or permission, abandoned part of

a school plan that had effectively and permanently achieved

full integration, and returned to zones that recreated

precisely the segregation that required the court-ordered plan

to begin with. Whatever "unitariness" may mean, it cannot

mean be that a school board may resurrect conditions of

racial segregation that are beyond the power of a federal

29

court to remedy in the absence of a finding that the action

was taken with invidious discriminatory motivation.

III.

Alternatively, if a finding of "unitariness" means that a

school system may make changes in pupil assignments

without court review in the absence of racially

discriminatory motivation, such a finding must be based on

a searching factual inquiry that establishes that all the

circumstances and conditions that required the imposition of

a desegregation decree have disappeared. Thus, there must

be a determination that the system will remain unitary in the

face of any change in pupil assignment procedures. Such an

inquiry and such findings were not made in the present case,

and at the least the case must be remanded to the court of

appeals for a determination of the meaning of the various

findings of "unitariness" made by the district court.

30

ARGUMENT

In trodu ction

In order to focus our argument, respondents first wish

to point out what this case is not about:

1. This is not a "de facto" school case, where there

had been a long-standing tradition of neighborhood schools

that became racially isolated because of housing patterns

unrelated to governmental actions. This is a classic de jure

case involving a school district that had schools rigidly

segregated by law and that adopted neighborhood schools

only after Brown 1 and Brown II. Moreover, neighborhood

schools were imposed on housing that was rigidly segregated

as a result of state action, and the adoption of neighborhood

schools increased and exacerbated this residential

segregation.

31

2. This is not a "Spangler"20 case, where a district

court required the modification of a desegregation plan to

accommodate shifting residential patterns that had led to

some schools becoming racially unbalanced. Here, there

was in place a plan that successfully and completely

desegregated all the schools in the district.21 The school

district, without the approval of the district court, abandoned

part of it and resegregated ten elementary schools.

3. This case does not involve a "small number o f one-

race schools" within the meaning of Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. o fE duc., 402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971). Forty

per cent of Afro-American children in grades 1-4 attend ten

schools that are nearly 100% Afro-American. At the same

time, thirteen other elementary schools have become more

20 Pasadena City Board o f Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976).

21 Thus, the schools serving grades 5-12 continue to follow the

Finger Plan and remain desegregated. In addition, the faculties at all

grade levels are currently fully integrated.

32

than 80% white because of the re-imposition of

neighborhood schools.22

The sole issue in this case is whether the Oklahoma

City school district can abandon an effective desegregation

plan, relegate 40% of Afro-American elementary pupils to

racially segregated schools, and take no other steps to

overcome the vestiges of segregation. We urge that such a

result is wholly inconsistent with the promise of Brown 1 and

II, with the mandate of Green v. County School Bd. o f New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and with the basic

principles of equity applicable to school desegregation

lawsuits under Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f

Educ., supra.

22 Dowell v. Bd. o f Education o f Oklahoma City Public Schools, 677

F. Supp. 1503, 1509-1510 (W.D. Okla. 1987).

33

I.

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASES ARE GOVERNED

BY THE EQUITABLE PRINCIPLES ESTABLISHED

BY U N IT E D S T A T E S v. S W IF T & CO.

A. U n ited S ta tes v. S w ift & Co. Governs This Case.

It is established equity jurisprudence that a permanent

injunction remains in effect and is subject to the court’s

enforcement and implementation at any time, unless and

until it is dissolved pursuant to the procedure and under the

standard specified by the familiar rule of United States v.

Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932). Swift recognized that a

court in equity retains the power to modify an injunction,

which necessarily looks to the future, if the injunction "has

been turned through changing circumstances into an

instrument of wrong." 286 at 115.23 It is not enough that

23 The power exists "by force of principles inherent in the jurisdiction

of the chancery." 286 U.S. at 114. As noted in 11 Wright & Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure, § 2961, p. 599, the authority "has its

roots in the histone power of chancery to modify or vacate its decrees ‘as

events may shape the need.’" Lord Bacon’s Ordinances, adopted in

1618, provided:

(continued...)

34

the defendants "be better off if the injunction is relaxed;"

they must be "suffering hardship so extreme and unexpected

as to justify [the court] in saying that they are the victims of

oppression." Id., at 119.

Nothing less than a clear showing of grievous

wrong evoked by new and unforseen conditions

should lead us to change what was decreed after

years of litigation . . . .

Id., at 119. Central to that showing is a demonstration that

the changes in circumstances "are so important that dangers,

once substantial, have become attenuated to a shadow." Id.

(Emphasis added). 23

23(... continued)

No decree shall be reversed, altered, or explained . . . but

upon bill of review: and no bill of review shall be admitted,

except it contain either error in law, appearing in the body of

the decree without farther examination of matters in fact, or

some new matter which hath risen in time after the decree,

and not any new proof which might have been used when the

decree was made: . . . .

7 Bacon, Works 759 (Spedding ed. 1879)(emphasis added). Cases as

early as 1545 permitted modification of an equitable decree on the basis

of new matter. See Developments in the Law, Injunctions, 78 Harv, L.

Rev. 994, 1080-1086 (1965) and Note, Finality o f Equity Decrees in the

Light o f Subsequent Events, 59 Harv. L. Rev. 957-966 (1946).

35

The holding of Swift has been consistently reaffirmed by

this Court,24 and has been applied in a wide variety of

circumstances and types of cases by the lower federal

courts.25 The applicability of Swift to school desegregation

cases was explicitly recognized by this Court in Pasadena

City Board o f Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 437

(1976); that conclusion necessarily flowed from the holding

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc . , supra, that

school desegregation cases are governed by the same

standards as are all other cases that lie in equity. 402 U.S.

24 See, e.g. , United. States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244, 247-249 (196S)(Swift reaffirmed, held not to prevent

modification of a decree on petition of plaintiff in order to achieve the

purposes of the original decree rather than to nullify it); System

Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (196l)(Swift reaffirmed, held

that it was consistent with its principles to modify an injunction to make

it consistent with an amendment to a statute that was the basis for the

injunction’s issuance). The decree in Swift itself survived another attempt

to modify it in 1960 (United States v. Swift & Co., 189 F. Supp. 885

(D.C. 111. 1960), ajf’d per curiam, 367 U.S. 909 (1961)), and was still

in force more than 50 years after it was entered. United States v.

Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971).

23 See the cases discussed in 11 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 2961 and in 7 Moore, Moore’s Federal Practice t

60.26[4],

36

at 15.

Thus, there is no place in school desegregation litigation

for a "unitariness" finding that is based on a lesser standard

than Swift's and that thereby undoes the permanent character

of the permanent injunction that the plaintiffs have won and

to which they are entitled upon proof of a constitutional

violation. In the present case the finding of "unitariness" in

1977, whatever that elusive term might have meant, left the

permanent injunction in full effect and left the district court

and the respondents with the expectation that it would be

followed by the school district; indeed, the injunction was

followed in every respect for eight years until it was

unilaterally abandoned with regard to the elementary grades

in 1984.26

26 It is because of these facts that the issue of whether respondents

are "bound" by the 1977 finding of unitariness because they did not

appeal the order is of absolutely no consequence. In short, there was

nothing for respondents to appeal, since the order did not by its terms or

effect in any way adversely affect their rights. The permanent injunction

requiring the implementation of the Finger Plan remained in place and

(continued...)

37

Under these principles, a "unitariness” finding is a

convenient instrument for marking the point at which a

district court gives up its former active supervision over

pupil assignment procedures and other school board actions

that affect the racial distribution of students among schools.

Upon a finding that the school system has a "unitary"

character, the court may properly permit the board to

implement such actions henceforth without prior approval.

But the board remains under a continuing obligation to

maintain a school system from which segregation has been

completely and permanently eliminated; and its actions

2S(.. .continued)

the district court expressly stated in its order that it did not foresee any

"dismantlement of the Plan." In fact there was none until 1984, when

the school district abandoned the plan in part without any notice to the

court or plaintiffs, and without filing a motion under Rule 60(b), F. R.

Civ. Proc. seeking relief from the court’s judgment through dissolution

or modification of the permanent injunction. It was not until 1985, when

the district court retroactively interpreted its 1977 order to mean that

plaintiffs had no enforceable rights under the still undissolved permanent

injunction, that there was any need or obligation to appeal; the plaintiffs

did so and the court of appeals reversed the district court’s order. The

district court did not actually dissolve the permanent injunction until

1987. 677 F. Supp. at 1526.

38

remain subject to the court’s review for consistency with that

obligation.

Thus, once a state or subdivision of a state has been

found, as have Oklahoma and the Oklahoma School Board,

to have violated the Fourteenth Amendment by deliberately

segregating Afro-American children from white children in

the public schools, a permanent injunction promising a

permanent correction of that constitutional violation is in

order. The obligation of the board to conduct its affairs in

such a way as to prevent resegregation and the power of the

court to review the board’s actions to assure that

resegregation does not occur are coextensive with the

permanent injunction. Of course, as here, the

implementation of a fully corrective injunction can lead to

the dismissal of the action without the dissolution of the

39

injunction.27

Under Swift & Co. a school district, like any other

equity defendant, can be relieved from a permanent

injunction under appropriate circumstances. But those

circumstances must amount to a "clear showing of grievous

wrong evoked by new and unforseen conditions," 286 U.S.

at 119.28 As the Tenth Circuit properly held, the Oklahoma

City Board of Education made no such showing here. First,

the underlying circumstances that required the terms of the

injunction had not changed at all.29 To the contrary, the

27 As noted at n. 24, supra, the injunction in Swift itself was still in

effect in 1971. It is our understanding that there are similarly

outstanding permanent injunctions in a large number of anti-trust cases

brought by the United States going back to the passage of the Sherman

Anti-Trust Act; m the majority of these cases the action has been

dismissed, but the injunction remains in force and is enforceable.

28 The alternative basis for relief from an injunction, a change in the

substantive law that gave rise to the need for equitable relief (see

Pennsylvania v. Wheeling & B. Bridge Co., 59 U.S. 421 (1856); System

Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (1961)), does not apply here.

29 Thus, continuation of the injunction here as long as the underlying

condition of residential segregation persists would "not extend [it] beyond

the time required to remedy the effects of past intentional

(continued...)

40

facts demonstrated that returning to the same neighborhood

schools as in 1971 meant the return to the same segregated

schools.29 30 Since the continuing existence of the Afro-

American ghetto, which had been created by official action,

was the result of antipathy of whites to moving into an area

identified as minority, the vestiges of the prior segregated

system remained. Second, the justifications advanced by the

school board for abandoning the plan in grades 1-4 did not

amount to "grievous wrong." Respondents agreed that the

burdens on the Afro-American community had been

inequitable and put forward alternative plans that would have

corrected the inadequacies of the Finger Plan without

29(... continued)

discrimination." Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. o fE d ., 611 F.2d 1239,

1245, n. 5 (9th Cir. 1979)(concurring opinion of then Judge Kennedy).

30 It must be kept in mind that the effect of adopting neighborhood

schools in 1955 "was to erect new boundary lines for the purpose of

school attendance in a district where no such lines had previously existed,

and where a dual school system had long flourished. ” Wright v. Council

o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 460 (1972). Just as in Wright both

the original adoption of neighborhood school attendance zones as well as

their re-adoption in 1977 "must be judged according to whether it hinders

or furthers the process of school desegregation." Id.

41

resegregating the schools. The district court held, however,

that the respondents were precluded from obtaining any

further remedial relief because of the so-called "unitary

status" of the Oklahoma City schools, citing the fear of

"white flight" if white students were bused and purported

additional costs. 677 F.Supp. at 1525-26. In any event,

even assuming respondents’ plans were faulty in some

respect, this in no way relieved the school board from

coming forward with its own alternative plan that could both

maintain desegregation while correcting any inequities.

B. The School Board Has Failed to Justify

Resegregating Schools Under Even a Lesser

Standard than Sw ift.

Even if the exacting Swift & Co. test were not the

applicable standard, the school board has shown no sufficient

justification for relief from the injunction that goes so far as

to permit the consignment of 40% of Oklahoma City’s Afro-

42

American elementary school children to virtually all-Afro-

American schools. Any test for modifying a school

desegregation decree must, at the least, be consistent with

the general remedial principles announced in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., supra. Under Swann,

when substantially one-race schools persist or are re

introduced in a school system "with a history of

segregation," the court that decreed injunctive relief is

required to "scrutinize such schools, and the burden . . . [is]

upon the school authorities to satisfy the court that their

racial composition is not the result of present or past

discriminatory action on their part." 402 U.S. at 26.

Here, the board neither did nor could meet that burden.

The key question was whether the existing residential

segregation that produced the ten all-Afro-American schools

was linked to the residential segregation found by the district

court to be caused by official actions, including the

43

imposition of a neighborhood school plan on existing

residential segregation in 1955. As described above, in 1967

and 1972 the district court held that neighborhood schools

could not be used precisely because they exacerbated housing

segregation by destroying integrated neighborhoods.

Nevertheless, the district court later held that its two

"unitary" findings mean that, in a mere five to thirteen

years, by 1977 or 1985, the effect of all governmental

actions that contributed to residential segregation had become

attenuated to the point that the school board could revert to

precisely the same school zones that had helped to create the

segregation in the first place.

Respondents urged below, and continue to urge here,

that this finding was clearly erroneous because it failed to

take into account all of the testimony of petitioner’s expert

44

upon whose opinion the court based its finding.31 As set out

in the Statement above, on both direct and cross examination

Dr. Clark testified that because of "preference" that included

at least an element of racial prejudice, whites would not

move into a neighborhood that was more than 25-30% Afro-

American. Thus, although some Afro-American families

had, in the period 1972-1985, moved out of the ghetto

created and maintained by state action, whites had not

moved in. As Dr. Clark acknowledged, the refusal of

whites to move in and thereby integrate the all-Afro-

American schools re-established in 1985 was linked in

significant degree to the past discriminatory actions by state

and local governments and by the school board when it

adopted neighborhood schools in the first instance.32 The

31 The court of appeals agreed that the district court’s finding was

clearly erroneous since its review of the entire evidence left it with "‘the

definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed.’" 890

F.2d at 1504.

See pp. 20-22, supra.32

45

district court simply ignored this part of Dr. Clark’s

testimony when it made its findings. While, as the finder of

fact, the district court was free to credit the testimony of

petitioner’s expert, it could not accept some of that

testimony and disregard, without explanation, the rest of it,

particularly when it was consistent with the testimony as a

whole and corroborated by that of respondents’ expert.

Further, the conclusion of the district court that the

effects of the school district’s past discriminatory actions had

become "attenuated beyond a shadow" was wrong as a

matter of law. In Oklahoma City there were sixty-five years

of state imposed segregated schools and fifty years of state

enforced residential segregation that was exacerbated by

seventeen years of "neighborhood" schools. It would be

totally contrary to the spirit and intent of Green and Swann

to conclude that a school district can escape its affirmative

obligations to eliminate all vestiges of discrimination by

46

complying with a court decree that produces integration for

one generation of students.33 To argue that the same ten

schools that are now all-Afro-American as were in 1972 are

not vestiges of segregation is to ignore Swann’s recognition

that the drawing of zone lines and the placement of schools

are "potent weapon[s] for creating or maintaining a state-

segregated school system." 402 U.S. at 21. There is

simply no evidence in this record that meets the school

board’s burden of demonstrating that the natural effects of its

policies from statehood to 1972 have been dissipated. As

Swann holds:

People gravitate toward school facilities, just as

schools are located in response to the needs of

people. The location of schools may thus influence

33 It is similarly contrary to the holdings of Wright v. Council o f City

o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) and United States v. Scotland Neck City

Bd. o f Ed., 407 U.S. 484 (1972) to hold that an action of a school board

with a history of de jure segregation must have an invidious

discriminatory motive in order to violate the affirmative duty to

desegregate. Those decisions stand squarely for the proposition that if

an action has the effect of hindering the process of desegregation then it

must be enjoined. It cannot be denied that the action of petitioner here

had precisely such an effect.

47

the patterns of residential development of a

metropolitan area and have important impact on

composition of inner-city neighborhoods.

402 U.S. at 20-21. Precisely this occurred in Oklahoma

City; the school board has done nothing to correct the

underlying condition, which remains the most dramatic

vestige of the dual system.

The district court sought to avoid this conclusion solely

because some Afro-Americans had, as a consequence of

federal, state, and local fair housing laws, been able to move

into areas from which they had once been barred by law.

But the fact that the proportion of Afro-Americans who live

in the ghetto has declined because some residents were

finally able to move out, in no way diminishes the fact that

the ghetto, which was created by state and city law and

intensified by acts of the school board, still exists because

whites will not move into it.

48

To summarize, a school system that has operated state-

mandated dual system segregated by race has a permanent

and continuing obligation to take affirmative steps to either

eliminate or neutralize the vestiges of that system. Once a

violation has been shown, plaintiffs are entitled to a

permanent injunction requiring such affirmative action. An

injunction may be dissolved only upon the showing required

by Swift or, in the alternative, by a showing that all vestiges

have been fully eliminated so that an injunction is no longer

necessary. The only consequence of a finding of

"unitariness" consistent with this view is that a district court

may relinquish active supervision of a school desegregation

case subject to its being reopened if there is, as here, a

deviation from the decree resulting in resegregation.

49

n.

ALTERNATIVELY, A FINDING OF UNITARINESS MAY

TERMINATE THE OBLIGATION TO ADJUST PUPIL

ASSIGNMENT PLANS TO ACCOUNT FOR

DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS

If the Court decides to approve the procedure of making

findings of "unitariness" that have more than the limited

consequences we have urged above, then the appropriate

effect of a finding of "unitariness" can be nothing more than

to terminate the school board’s and court’s obligation to

adjust pupil assignment plans from time to time. A

"unitariness" finding cannot properly be treated as licensing

the school board unilaterally to abrogate the plan that

produced "unitariness" and to restore the status quo ante.

As noted above, this case does not involve a situation in

which, after a school system has been found "unitary,"

subsequent demographic shifts create a new condition of

racial isolation in the public schools, and the federal court

50

that oversaw desegregation is asked to order additional

remedial measures to correct this new condition. That is the

situation that was explicitly described in Swann when the

Court said that at a certain point in a school desegregation

case:

Neither school authorities nor district courts are

constitutionally required to make year-by-year

adjustments of the racial composition of student

bodies once the affirmative duty to desegregate has

been accomplished and racial discrimination

through official action is eliminated from the

system.

402 U.S. at 31-32.34 See also Pasadena City Board ofEduc.

v. Spangler, A l l U.S. 424, 435-36 (1976). The Tenth

Circuit took the view that in the situation contemplated by

j4 The Court went on:

This does not mean that federal courts are without

power to deal with future problems; but in the

absence of a showing that either the school

authorities or some other agency of the State has

deliberately attempted to fix or alter demographic

patterns to affect the racial composition of the

schools, further intervention by a district court

should not be necessary.

Id. , at 32.

51

Swann and Spangler no further judicial relief would be

warranted, saying "a federal district court should not [thus]

attempt an interminable supervision over the affairs of a

school district." 890 F.2d at 1492 n. 17. For the purposes

of the present argument II, we accept that premise.

In light of the premise, this case involves a situation

that is the precise opposite of that contemplated by Swann.

Here the school board is not seeking to retain a pupil

assignment plan that produced an acceptable level of

desegregation in the first instance and is later challenged as

inadequate by litigants asking the court to "update" the plan

to keep abreast of the latest population shifts.35 To the

contrary, here the school board itself acted unilaterally to

reverse the pupil assignment plan that had made the system

35 Respondents put forward two proposed modifications of the Finger

Plan only in response to the school board’s action. Their purpose was

to demonstrate that there were feasible means of maintaining

desegregation in all of the elementary schools while meeting the

ostensible reasons for reintroducing neighborhood schools in grades 1-4.

52

unitary; it reinstated geographic attendance zones that had

been previously found by the district court to perpetuate and

exacerbate racial segregation; and it thereby restored

precisely the same pattern of racial separation in the schools

that had existed before the unitariness finding was made.

As the court of appeals pointed out, "[i]t is uncontested

that the contents of the [board’s new] plan are contrary to

the explicit dictates of the injunction1' that produced

desegregation (890 F.2d at 1492-93); and the new plan "has

the effect of reviving those conditions that necessitated a

remedy in the first instance" (890 F.2d at 1499).

Specifically, the restoration of the previous geographic

zoning scheme re-created virtually all-Afro-American student

bodies in ten elementary schools that had been found to be

identifiably Afro-American in 1972. Concomitantly, 13

schools that had student bodies 99.5% to 100% white in

1971-1972 had student bodies from 80% to 86.2% white in

53

1985-86, in a school district that is only 50.7% white.36

A finding of "unitariness" at the least supposes that a

school board will continue to keep faith with the foundations

of the finding. It does not empower the board to topple

those foundations, resurrect conditions of racial segregation,

and then insist that the conditions are beyond judicial

correction unless the board is proven to have acted with an

invidious discriminatory motivation in turning the clock

back. Such a result is wholly inconsistent with the mandate

of Green v. School Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430, 438 (1968) that all vestiges of the prior segregated

system be eliminated "root and branch," as well as the

holdings of Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972), and United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. o f

36 The thirteen schools are Adams, Buchanan, Coolidge, Fillmore,

Hays, Hillcrest, Kaiser, Lafayette, Linwood, Prairie Queen, Quail Creek,

Rancho, and Ridgeview. Compare the tables at 338 F. Supp. at 1260,

showing the 1971-72 enrollments, and at 677 F. Supp. at 1509-10,

showing the 1985-86 enrollments.

54

Educ., 407 U.S. 484 (1972), that actions by a school system

that is under the duty to desegregate must be judged by their

effect, rather than by their purpose.

in.

ALTERNATIVELY, A SYSTEM CAN BE "UNITARY"

ONLY UPON A FINDING THAT IT WILL REMAIN

SO IN THE FACE OF A N Y CHANGES IN

PUPIL ASSIGNMENT POLICIES

Petitioner takes the position that a finding of

"unitariness" should be given the effect of forbidding district

courts to review and correct school board actions that re

introduce conditions of racial isolation except upon a

showing of a new constitutional violation committed with

racially discriminatory motivation. This position, however,

is fundamentally at odds with the holdings of Wright v.

Council o f City o f Emporia, supra, and United States v.

Scotland Neck City Bd. o f Educ., supra, unless the finding

has been entered on the basis of underlying factual findings

55

that the system will remain unitary in the face of any non-

invidiously motivated change in pupil assignment procedures

that the board may subsequently adopt, including immediate

reversion to the status quo ante.

The logic under which the petitioner and the district

court argue that the 1977 "unitariness" finding authorized the

board to abandon the pupil assignment plan that had made

the school district "unitary" and to regress to an earlier

neighborhood attendance zone scheme - namely, that after

a finding of "unitariness’ a school board is free to do

whatever it wants in the way of pupil assignment so long as

it is not shown to be acting with a segregative purpose -

would equally justify the same regressive action by a school

board on the first day after a unitariness finding is entered.

But if this is to be the consequence of a unitariness

finding, then the meaning of a unitariness finding must fit

the consequence. The meaning must be that a school system

56

has become sufficiently stabilized as a unitary one that it

will remain unitary even on the supposition that the school

board reverts, the very next day, to the identical geographic

zones that previously had to be abolished to achieve

desegregation. For example, if the "unitary" finding in this

case had been based on underlying findings that over the

years the Afro-American ghetto had been substantially

integrated and that the Afro-American population was

distributed throughout the school district, such a finding

would permit the school district to re-adopt the earlier

geographic zones since the system would remain "unitary."

Thus, at a minimum the district court must conduct a

searching inquiry into the status of the system overall and

make findings as to each of the factors identified in Green v.

New Kent County School Bd., 391 U.S. at 435, Swann, 402

U.S. at 18-21, and Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977)

as indicia that the vestiges of the prior system have been

57

removed and not simply neutralized by the desegregation

plan. As Green admonishes (391 U.S. at 439), such an

inquiry and findings must be specific to the case and not

simply be a declaration of "unitariness" in the abstract.37

Thus, a predicate is a hearing at which the parties and the

court would investigate in detail whether all the

circumstances that led to the entry of the order in the first

place had been dissipated in fact. The burden would at all

times be on the school district to demonstrate that none of

the conditions that were indicia of a dual system remained.

Of course, given the facts in this case the 1977

"unitariness" finding could not and did not meet these

standards. The district court itself, both through its

questions at the 1975 hearing and its statement when it

37 As noted in the Brief Amici Curiae of the Council of the Great

City Schools, et al., at pages 13- 15, the inquiry must include a

determination that the school district has fully complied with all

outstanding court orders and has demonstrated its good faith commitment

to carrying out its constitutional obligations.

58

terminated the case in 1977, expressed the clear expectation

that the school board would not revert to the same zones if

the system were found to be unitary and the case dismissed.

Even after eight years, however, when the board did go

back to the same zones the result was to recreate the same

segregated schools that the plan was instituted to abolish

since the state-created ghetto that required the entry of the

plan was still in existence. Thus, it is impossible to

conclude that all vestiges of the prior de jure segregated

system had been eliminated "root and branch."

Therefore, this Court should conclude that the district

court’s unitariness finding was not based on a sufficient

factual predicate and affirm the decision of the Tenth

Circuit. At the least, the case must be sent back to the

Tenth Circuit to determine the meaning of the various

"unitariness" findings made by the district court and review

them under the legal standard set out in this Part III.

59

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court of

appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

L ewis B arber , J r .

B arber/T ra viola

1523 N.E. 23rd Street

Oklahoma City, OK 73111

(405) 424-5201

J ohn W. W alker

J ohn W. W a lker , P.A.

1723 So. Broadway

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3758

J anell M. B yrd

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

J ulius L eV onne C hambers

C harles Stephen R alston

*N orman J. C hachkin

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212)-219-1900

A nthony G. A msterdam

New York University Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, N.Y. 10012

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys fo r Respondents