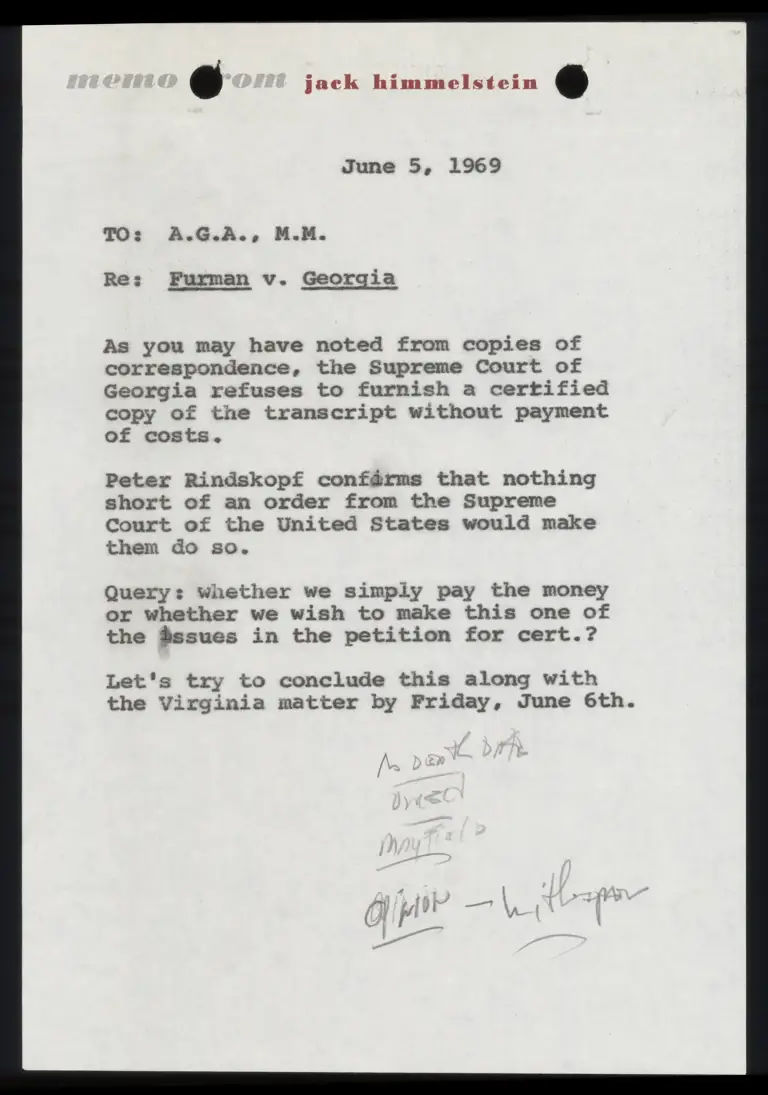

Memo from Himmelstein to Amsterdam and Meltsner

Correspondence

June 5, 1969

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Memo from Himmelstein to Amsterdam and Meltsner, 1969. 3ca5288b-b525-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76ea2ac7-42e0-487d-89fd-c05c83216df0/memo-from-himmelstein-to-amsterdam-and-meltsner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

% | jack himmelstein

June 5, 1969

A.G.A., M.M.

Re: Furman v. Georgia

As you may have noted from copies of

correspondence, the Supreme Court of

Georgia refuses to furnish a certified

copy of the transcript without payment

of costs.

Peter Rindskopf conférms that nothing

short of an order from the Supreme

Court of the United States would make

them do so.

Query: whether we simply pay the money

or whether we wish to make this one of

the #issues in the petition for cert.?

Let's try to conclude this along with

the Virginia matter by Friday, June 6th.