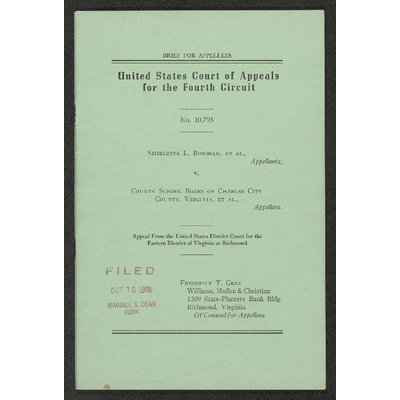

Brief for Appellees -- Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City County

Public Court Documents

October 10, 1966

28 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Brief for Appellees -- Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City County, 1966. f1c26200-6d31-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/76f3756e-6e86-42bd-a897-70749e21f6e2/brief-for-appellees-bowman-v-county-school-board-of-charles-city-county. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,793

SHIRLETTE L. BowMAN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

VY.

County ScHoOoL BoArD oF CHARLES City

CoUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal From the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia at Richmond

FrepERICK T. GRAY

Williams, Mullen & Christian

1309 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Of Counsel for Appellees

ANLIDILC C NEAR

MAURILE Oo. | EAN

CLERK

|

|

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT OF TRE CASE a er 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS i er rs 2

PLAN FOR DESEGREGATIONR OF SCHOOLS oo. st ee. 3

Tne QUESTION INVOLVED ci ioci oir immominchmnnscansihsaatyssaceionss 10

ARGUMENT

L. Frecdom of CoC i it mea ai 10

11. The Bacully Question ...... oo. i iieiacins ins airnionnasss 17

CONCLUSION i. i a si ag 20

TABLE OF CASES

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347: 10S. 497 (0 cs deesisiacesmainssins 12, 13

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310

11.13, 17.15

Brown v. Beard of Education, 139 Fed. Supp. 470 ..................... 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 creme. 14

Rovers v- Pal, 300 1) OS, IO rer riinossosissucscarssneeraonzesstiionernnhss 18

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Education ...... F224... , 4th

Cl I IO cr nese besitos rene 17

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,753

SHIRLETTE L. BowMAN, ET AL,

Appellants,

V.

County ScHoOL BoaArDp oF CHARLES CITY

County, VIRGINIA, ET AL,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On July 15, 1966, not three months ago, the District

Court approved the plan for the operation of the public

schools of Charles City County, Virginia, as filed with the

District Court of May 10, 1966, and as supplemented by

action of the School Board of June 27, 1966, and filed with

the Court of June 30, 1966. As a part of its approval of the

plan the Court required a registration period prior to the

opening of schools in the fall of 1966.

Obviously, on the record before this Court, there is and

can be no evidence as to changes in the composition of

student body or faculty as a result of the plan so recently

made operative.

2

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The facts as stated by the Appellants are largely those

shown to have existed at the time the answer to inter-

rogatories was filed on June 10, 1965. IT Is IMPORTANT

To Note THAT THE INTERROGATORIES WERE FILED MAY

7, 1965, ANp Nor 1966 Anp THE ANSWERS THERETO

WERE FiLep June 10, 1965, Anp Not 1966 As THE

APPENDIX To APPELLANT'S BRIEF INDICATES ON PAGES

2 AND 8 RESPECTIVELY.

Since that time pupils and their parents have had two

opportunities to select the school of their choice and the

school board has commenced operations under the faculty

supplement to its freedom of choice plan. Obviously, the

statistical data for the 1964-65 school session is now of

little value. As an example of this fact the memorandum of

the District Court filed May 17, 1966, correctly stated

“There is no integration of faculty members in the Negro

and white schools.” The Court thereupon permitted the

submission of an amendment to the school plan dealing with

staff employment and assignment and on June 30, 1966,

the school board reported that a Negro teacher has been em-

ployed to teach at formerly all white Charles City School

and “earnest but thus far unsuccessful effort has been

made and is continuing to secure white teachers for every

existing vacancy in Negro schools of Charles City County

(9 vacancies).” (Appendix to Appellant’s Brief, p. 35)

The essential fact to the case is therefore, that the School

Board has adopted and has in operation the following

plan:

3

PLAN FOR SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

CHARLES CITY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

PROVIDENCE FORGE, VIRGINIA

Filed May 10, 1966

I. ANNUAL Frezpom or CHOICE OF SCHOOLS

A.: The School: Board of Charles City. County has

adopted a policy of complete freedom of choice to be offered

annually in all grades of all schools without regard to race,

color, or national origin.

B. The choice is granted to parents, guardians and per-

sons acting as parents (hereafter called “parents”) and

their children. Teachers, principals and other school person-

nel are not permitted to advise, recommend or otherwise

influence choices. They are not permitted to favor or penal-

ize children because of choices.

11. Puprnis Entering Finst GRADE

Registration for the first grade will take place, after con-

spicuous publication twice in Richmond papers, between

April 7, 1966 and May 31, 1966, from 9:00 A.M. to 2:00

P.M. When registering, the parent will complete a Choice

of School Form for the child. The child may be registered

at any elementary school in this system, and the choice made

may be for that school or for any other elementary school

in the system. The provisions of Section VI of this plan

with respect to overcrowding shall apply in the assignment

to schools of children entering first grade.

111. Pupriis Entering Ortuer GRADES

A. Each parent will be sent a letter annually explaining

the provisions of the plan, together with a Choice of School

|

|

4

Form and a self-addressed return envelope, at least 15 days

before the date when the form must be returned. Choice

forms and copies of the letter to parents will also be readily

available to parents or students and the general public in

the school offices during regular business hours. Section VI

applies.

B. The choice of school form must be either mailed or

brought to any school or to the Superintendent’s office by

May 31st of each year. Pupils entering grade one (1) of

the elementary school or grade eight (8) of the high school

must express a choice as a condition for enrollment. Any

pupil in grades other than grades 1 and 8 for whom a choice

of school is not obtained will be assigned to the school he

is now attending.

IV. PuriLs NEwLY ENTERING SCHOOL SYSTEM OR

CuanciNe RESIDENCE WitHIN IT

A. Parents of children moving into the area served by

this school system, or changing their residence within it,

after the registration period is completed but before the

opening of the school year, will have the same opportunity

to choose their children’s school just before school opens

during the week beginning August 30th, by completing a

Choice of School Form, The child may be registered at

any school in the system containing the grade he will enter,

and the choice made may be for that school or for any other

such school in the system. However, first preference in

choice of schools will be given to those whose Choice of

School Form is returned by the final date for making choice

in the regular registration period. Otherwise, Section VI

applies.

B. Children moving into the area served by this school

system, or changing their residence within it, after the late

registration period referred to above but before the next

regular registration period, shall be provided with the

Choice of School Form. This has been done in the past.

V. RESIDENT AND NON-RESIDENT ATTENDANCE

This system will not accept non-resident students, nor will

it make arrangements for resident students to attend schools

in other school systems where either action would tend to

preserve segregation or minimize desegregtion. Any ar-

rangement made for non-resident students to attend public

schools in this system, or for resident students to attend

public schools in another system, will assure that such stu-

dents will be assigned without regard to race, color, or na-

tional origin, and such arrangement will be explained fully

in an attachment made a part of this plan.

V1. OVERCROWDING

A. No choice will be denied for any reason other than

overcrowding. Where a school would become overcrowded

if all choices for that school were granted, pupils choosing

that school will be assigned so that they may attend the

school of their choice nearest to their homes. No preference

will be given for prior attendance at the school.

B. The Board does not anticipate overcrowding. All

requests have been granted during the past three years.

(The Board will make provisions to take care of all requests

for transfers.)

V1I. TRANSPORTATION

Transportation will be provided on an equal basis with-

out segregation or other discrimination because of race,

color, or national origin. The right to attend any school in

6

the system will not be restricted by transportation policies

or practices. To the maximum extent feasible, busses will be

routed so as to serve each pupil choosing any school in the

system. In any event, every student eligible for bussing shall

be transported to the school of his choice if he chooses either

formerly white, Negro or Indian schools.

VIII. SErvicES, FACILITIES, ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMS

There shall be no discrimination based on race, color, or

national origin with respect to any services, facilities, activi-

ties and programs sponsored by or affiliated with the schools

of this school system.

IX. STAFF DESEGREGATION

A. Teacher and staff desegregation is a necessary part of

school desegregation. Steps shall be taken beginning with

school year 1965-66 toward elimination of segregation of

teaching and staff personnel based on race, color, or national

origin, including joint faculty meetings, in-service pro-

grams, workshops, other professional meetings and other

steps as set forth in Attachment C.

B. The race, color, or national origin of pupils will not

be a factor in the initial assignment to a particular school or

within a school of teachers, administrators, or other em-

ployees who serve pupils, beginning in 1966-67.

C. This school system will not demote or refuse to re-

employ principals, teachers and other staff members who

serve pupils, on the basis of race, color, or national origin;

this includes any demotion or failure to re-employ staff

members because of actual or expected loss of enrollment

in a school.

7

D. Attachment D hereto consists of a tabular statement,

broken down by race, showing: 1) the number of faculty

and staff members employed by this system in 1964-65;

2) comparable data for 1965-66; 3) the number of such per-

sonnel demoted, discharged or not reemployed for 1965-66;

4) the number of such personnel newly employed for 1965-

66. Attachment D further consists of a certification that in

each case of demotion, discharge or failure to re-employ,

such action was taken wholly without regard to race, color,

or national origin.

X. Pusricity AND COMMUNITY PREPARATION

Immediately upon the acceptance of this plan by the U.S.

Commissioner of Education, and once a month before final

date of making choices in 1966, copies of this plan will be

made available to all interested citizens and will be given

to all television and radio stations and all newspapers serv-

ing this area. They will be asked to give conspicuous pub-

licity to the plan. If the plan does not receive prominent

news coverage in the Richmond papers, an advertisement

of not less than one-half page will be conspicuously placed

in all newspapers serving this area. The advertisement or

other newspaper coverage will set forth the text of the plan,

the letter to parents and the Choice of School Form. Similar

prominent notice of the choice provision will be arranged

for at least once a month thereafter until the final date for

making choice. In addition, meetings and conferences will

be called to inform all school system staff members of, and

to prepare them for, the school desegregation process, in-

cluding staff desegregation. Similar meetings will be held

to inform Parent-Teacher Associations and other local

community organizations of the details of the plan, to pre-

pare them for the changes that will take place.

8

X11. CertiricaTiON

This plan of desegregation was duly adopted by the

Charles City County School Board at a meeting duly called

and held on August 6, 1965.

Signed: Byro W. Long,

Superintendent

Supplement to Plan for School Desegregation

Presented by The County School Board of Charles City County

Adopted June 27, 1966 Filed June 30, 1966

The School Board of Charles City County recognizes its

responsibility to employ, assign, promote and discharge

teachers and other professional personnel of the school sys-

tems without regard to race, color or national origin. We

further recognize our obligation to take all reasonable steps

to eliminate existing racial segregation of faculty that has

resulted from the past operation of a dual system based

upon race or color.

In the recruitment, selection and assignment of staff, the

chief obligation is to provide the best possible education for

all children. The pattern of assignment of teachers and

other staff members among the various schools of this system

will not be such that only white teachers are sought for

predominantly white schools and only Negro teachers are

sought for predominantly Negro schools.

The following procedures will be followed to carry out

the above stated policy :

1. The best person will be sought for each position with-

out regard to race, and the Board will follow the policy of

assigning new personnel in a manner that will work towards

the desegregation of faculties.

9

2. Institutions, agencies, organizations, and individuals

that refer teacher applicants to the school system will be

informed of the above stated policy for faculty desegregation

and will be asked to so inform persons seeking referrals.

3. The School Board will take affirmative steps includ-

ing personal conferences with members of the present fac-

ulty to allow and encourage teachers presently employed to

accept transfers to schools in which the majority of the

faculty members are of a race different from that of the

teacher to be transferred.

4. No new teacher will be hereafter employed who is not

willing to accept assignment to a desegregated faculty or in

a desegregated school.

5. All Workshops and in-service training programs are

now and will continue to be conducted on a completely de-

segregated basis.

6. All members of the supervisory staff have been and

will continue to be assigned to cover schools, grades, teachers

and pupils without regard to race, color or national origin.

7. It is recognized that it is more desirous where possible,

to have more than one teacher of the minority race (white

or Negro) on a desegregated faculty.

8. All staff meetings and committee meetings that are

called to plan, choose materials, and to improve the total

educational process of the division are now and will continue

to be conducted on a completely desegregated basis.

9. All custodial help, cafeteria workers, maintenance

workers, bus mechanics and the like will continue to be em-

ployed without regard to race, color or national origin.

10. Arrangements will be made for teachers of one race

to visit and observe a classroom consisting of a teacher and

10

pupils of another race to promote acquaintance and under-

standing.

11. The School Board and superintendent will exercise

their best efforts, individually and collectively, to explain

this program to school patrons and other citizens of Charles

City County and to solicit their support of it.

As of this date the following has been accomplished inso-

far as employment is concerned :

1. Employed one Negro teacher to teach in formerly all

white Charles City School.

2. Earnest but thus far unsuccessful effort has been made

and is continuing to secure white teachers for every exist-

ing vacancy in Negro schools of Charles City County. (9

vacancies)

THE QUESTION INVOLVED

The only question involved in this appeal is whether

the plan for the operation of schools in Charles City County,

Virginia, is capable of being operated in such manner as will

prevent racial discrimination in those schools.

ARGUMENT

I

Freedom of Choice

The appellants apparently are having some difficulty estab-

lishing their footing as they seek to attack the principle of

“freedom of choice”. On page 7 of their brief they com-

plained that “during the pendency of the suit” the freedom

of choice plan was adopted but on page 8 they acknowledge

that since 1956 the parents of all pupils in Charles City

11

County, Virginia “had been afforded an unrestricted choice”

of the school which their children should attend.

Unless the “freedom of choice” principle approved in

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F.2d

310, is now to be declared invalid the admission by the ap-

pellants that there exists an “unrestricted choice” would

seem to bring the case squarely within the language of

Bradley:

“A system of free transfers is an acceptable device

for achieving legal desegregation of schools.”

Under the freedom of choice plan a 15 day choice period

is provided, all activities of the schools are covered, trans-

portation is without regard to race and no person may be

subjected to penalty or favor because of the choice made.

No real attack is made upon the operation of the plan—

the only attack made is upon the principle of free choice.

The movement which began to free the Negro from the in-

ability to exercise a choice because of race would now—rfor

purely racial motives—deny him the choice. The plaintiffs

say in effect there can be no free choice—there must be inter-

mixture. The desire of parents must fall before the desire of

those who would require “immediate total desegregation”.

In spite of the fact that every plaintiff in this law suit

admits the existence of an “unrestricted choice” they would

have the Court force others to do what they are free to do

already.

It is difficult to envision this as a bona fide action if the

parents are merely asking the Court to do for others that

which they can do by a mere application to the School Board.

This argument flys in the teeth of the very type relief which

was originally asked in the school cases. For example, James

M. Nabritt, III, one of counsel for the plaintiffs here, sug-

12

| gested a decree in the District of Columbia case. On April 11,

| 1955, in oral argument he said :

“Now, it would seem to me that this also could be

of assistance to the Court in dealing with the question

if, in a situation where the Court has as wide a super-

visory power as in this, the Court directed the courts

below here to enter a decree which is in effect, Mr.

Justice Frankfurter, this judgment reversed and cause

remanded to the District Court for proceedings not

inconsistent with this Court’s opinion, and entry of a

decree containing the following provisions:

“(1) All provisions of District of Columbia Code or

other legislative enactments, rules or regulations, re-

quiring, directing or permitting defendants to admin-

ister public schools in the District of Columbia on the

basis of race or color, or denying the admission or

petitioners or other Negros similarly situated to the

schools of their choice within the limits set by normal

geographic school districting on the basis of race or

color are unconstitutional and of no force or effect:

| “(2) Defendants, their agents, employees, servants

| and all other persons acting under their direction and

| supervision, are forthwith ordered to cease imposing

| distinctions based on race or color in the administration

of the public schools of the District of Columbia; and

are directed that each child eligible for public school

attendance in the District of Columbia be admitted to

the school of his choice not later than September, 1955

within the limits set by normal geographic school dis-

tricting;

“(3) The District Court is to retain jurisdiction to

make whatever further orders it deems appropriate to

carry out the foregoing ;”*

* See Page 75, Vol. I Transcript in Supreme Court of the United

States, April 11, 1955, Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497.

13

We shall point out later herein that the Court embodied

that free choice principle in its whole reasoning.

Actually at this stage it is clear that the law in the Fourth

Circuit is that a freedom of choice plan is a satisfactory

method of satisfying the constitutional requirements insofar

as pupil assignments are concerned. The remand of the

Bradley case for a hearing on the effect of faculty segre-

gation on a free choice plan in no wise detracts from the

validity of the obviously constitutional proposition of free

choice.

We have drifted so far in the long storm of this litigation

that the lighthouse may now be totally beyond our view but

perhaps we can remember what it looked like. We are still

dealing with constitutional limitations on the rights and

powers of the States. So far as counsel knows those powers

are limited in this and like cases by the Fourteenth Amend-

ment and specifically the “Equal Protection Clause”, or as in

Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, by the Due Process Clause of the

Fifth Amendment. What do these clauses provide?

‘ x * No state shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny any person within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws. * * *” (14th Amend-

ment )

*No person shall * * * he deprived of life liberty, or

property without due process of law; = * * (3{h

Amendment)

Can it be seriously contended that these clauses make un-

constitutional a system of free choice in the selection of the

public schools which a child will attend ? Can anyone honestly

contend that the first Brown decision so held! Let us examine

14

that decision and see! (Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483)

After holding that there is doubt that the Fourteenth

Amendment was intended to apply to public education at all

but that under today’s conditions it must be applied the

Court reached the heart of its reasoning:

“In Sweatt v. Painter (US) supra, in finding that a

segregated law school for Negroes could not provide

them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied

in large part on “those qualities which are incapable of

objective measurement but which make for greatness

in a law school.” In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 US 637,94 Led 1149, 70 S Ct 851, supra,

the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white

graduate school be treated like all other students, again

resorted to intangible considerations: “. . . his ability to

study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with

other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.”

Such considerations apply with added force to children

in grade and high schools. To separate them from

others of similar age and qualifications solely because

of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their

status in the community that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of

this separation on their educational opportunities was

well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court

which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the

Negro plaintiffs:

“ ‘Segregation of white and colored children in public

schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored chil-

dren. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of

the law ; for the policy of separating the races is usually

interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro

group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a

child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law,

therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational

15

and mental development of Negro children and to de-

prive them of some of the benefits they would receive

in a racial[ly] integrated school system.’

“Whatever may have been the extent of psycho-

logical knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this

finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any

language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding

is rejected.”

So it was legally enforced segregation which the Court

struck down—mnot freedom of choice. Indeed the Court

answers our question vividly in the fourth of five questions

which it had propounded for counsel to reargue. It asked

for still further argument on question 4 which was:

“4 Assuming it is decided that segregation in public

schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment

“(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing

that, within the limits set by normal geographic school

districting, Negro children should forthwith be ad-

matted to schools of their choice, or

“(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment to be

brought about from existing segregated systems to a

system not based on color distinctions?” (Emphasis

added)

Clearly all that concerned the Court was shall free choice

be granted now or can there be a gradual adjustment—?

Gradual adjustment to what? A school with racial balance?

No!— “to a system not based on color distinctions”. Indeed

the Court invited freedom of choice by the very nature of

the relief it was considering.

When one considers that the Court had difficulty determin-

ing that the 14th Amendment forbade compulsory segre-

16

gation—it is hard to understand how the plaintiffs so easily

find that it forbids free choice!

In attempting to understand the law as it has developed

in public school field, it is important to define the term

“segregation” and the term “desegregation”. Plaintiffs use

the term “segregation” as though it means any situation in

which all pupils in a particular school are of one race. They

apparently contend that even so defined segregation is un-

constitutional. If that be true it is unconstitutional for

Colonial Heights, Virginia, to engage in public education at

all for its entire population is white. Obviously then, a wholly

white or a wholly colored school does not necessarily violate

the Constitution. The missing ingredient is someone who is

denied admission—someone who is discriminated against.

Thus we come to the meaning of the term just as Webster

defines it.

In Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary the terms segre-

gate and segregation are defined as follows:

segregate—Set apart; separate; select. To separate

or cut off from others or from the general mass; to

1solate ; seclude.

segregation—Act of segregating or state of being seg-

regated ; separation from a general mass or main body;

specif., isolation or seclusion of a particular group of

persons.

We submit that when the State stops acting, segregation

no longer exists; for segregation is the result of action—

a setting apart, separation or selection.

Desegregate is defined in that same work as follows:

desegregate—To free (itself) of any law, provision, or

practice requiring isolation of the members of a partic-

17

ular race in separate units, esp. in military service or

in education.

Under that definition our schools are desegregated!

On remand to the District Court the original Brown case

resulted in the following statement by that Court:

“Desegregation does not mean that there must be an

intermingling of the races in all school districts. It

means only that they may not be prevented from inter-

mingling or going to school together because of race

or color.” (139 Fed. Supp. 470)

Bearing in mind those definitions and decisions we submit

that the Bradley case in this Court established as correct

principle and we need only determine now whether the adop-

tion of the faculty supplement to the “freedom of choice

plan” satisfies the Supreme Court’s action in the Bradley

case

II

The Faculty Question

The appellants complain that teachers are permitted a

“right to contract to teach in schools staffed exclusively with

teachers of his own race.” We were not aware that individual

citizens did not possess such right, however, it affords only

a moot question here. The school plan under consideration

provides machinery which will obviously eliminate a con-

dition in which there is a school staffed exclusively with

teachers of one race.

The District Court found the plan to be in compliance

with the requirements stated by this Court in Wheeler v.

Durham City Bd. of Education ...... F.2d.....— (4th Cir.

July 5, 1966). Paragraph 3 of the plan supplement (Page

18

9 herein) states that the School Board will take affirmative

steps, including personal conferences with members of the

present faculty, to allow and encourage teachers presently

employed to accept transfers to schools in which the majority

of the faculty members are of a race different from that of

the teacher to be transferred.”

The Supreme Court of the United States has not estab-

lished a requirement for the total desegregation of faculties

which appellants seek. ( Appellants’ Brief p. 10).

In Bradley the Court reversed the 4th Circuit because it

had approved “school desegregation plans without consider-

ing, at a full evidentiary hearing, the impact on those plans

of faculty allocation on all alleged racial basis.”

If the Court intended to say that there must be “total

desegregation of faculty” or even if it intended to say that

faculty segregation “per se” is unconstitutional or “per se”

makes invalid a pupil assignment plan it certainly could not

have chosen a poorer way to express its intentions. Why re-

mand for a hearing on what effect such segregation will have

if such segregation “per se” is void ?

The Court has held only that they are entitled to prove

that faculty segregation makes a free choice plan inadequate.

It:said that again in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 15 L.Ed.

265,

“Two theories would give students not yet in desegre-

gated grades sufficient interest to challenge racial al-

location of faculty: (1) that racial allocation of faculty

denies them equality of educational opportunity without

regard to segregation of pupils; and (2) that it renders

inadequate an otherwise constitutional pupil desegre-

gation plan soon to be applied to their grades. See

Bradley v. School Board, supra. Petitioners plainly had

standing to challenge racial allocation of faculty under

19

the first theory and thus they were improperly denied a

hearing on this issue.”

In this case there has been no showing and no effort to

show that the freedom of choice plan is inadequate—indeed

appellants admit an “unrestricted choice.”

We have made this argument out of a good faith belief

that we are not required under the Constitution to desegre-

gate the faculty. We likewise submit that the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 clearly does not require such and that the

“Guidelines” of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare in that area are ultra vires and indeed in direct

conflict with the express direction of the Congress.

Title VI of the Act contains the “fund cut-off” pro-

visions under which H.E.W. is operating. Section 604 pro-

vides,

“Nothing contained in this title shall be construed to

authorize action under this title by any department or

agency with respect to any employment practice of any

employer, employment agency, or labor organization

except where a primary objective of the Federal finan-

cial assistance is to provide employment.”

What could be clearer as to the policy of the Nation's

legislature?

Having made this argument in the good faith belief that

neither the Constitution nor the Civil Rights Act requires

it, we point out that the school plan provides for faculty

desegregation.

The desegregation of faculties in the public schools will

require time, patience, tolerance, good judgment on the part

of the administration, willingness on the part of teachers

and extreme care and skill on the part of those teachers

who commence the process. We submit that the plan which

20

we have adopted will permit a constructive beginning in a

field which could do much to destroy public education—we

sincerely trust that the Court will not substitute its judg-

ment for that of the school administration in an area in

which the administration’s judgment should be better cal-

culated to meet local conditions.

The plan as adopted provides for the employing of staff

without regard to race, desegregated administrative and

staff meetings, a provision that teachers employed in the

future will be subject to desegregated assignment and an

undertaking to encourage the faculty now employed to make

transfers which would desegregate. More should not be

required.

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that the judgment of the District

Court is plainly right and should be affirmed.

County ScHOoOL BoArD oF CHARLES

City CouNTY, VIRGINIA and

Byrp W. LoNg,

Division Superintendent of Schools

By FreDpERICK T. GRAY

Of Counsel

FreEpERICK T. GRAY

Williams, Mullen & Christian

1309 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia 23219