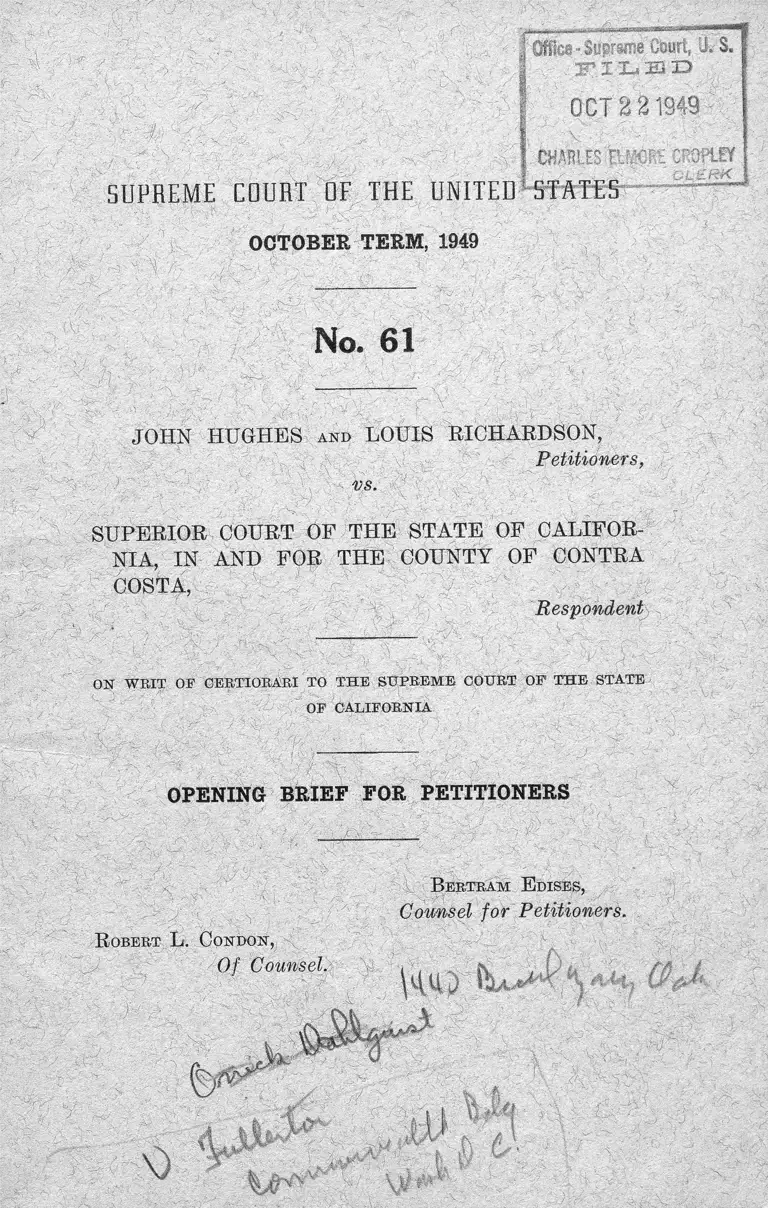

Hughes v. Superior Court of California in Contra Costa County Opening Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 22, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hughes v. Superior Court of California in Contra Costa County Opening Brief for Petitioners, 1949. eb289191-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77057510-3b75-4260-a383-2b192e1ee2c9/hughes-v-superior-court-of-california-in-contra-costa-county-opening-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

'O ffice - Supreme Court, 'J. S.

F I L E D

O C T 2 21849 -

CHARLES ELMGRL CROPLEY

S U P R E M E C OU R T OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1949

No. 61

JOHN HUGHES a n d LOUIS RICHARDSON,

Petitioners,

vs.

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFOR

NIA, IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF CONTRA

COSTA,

Respondent

ON WRIT OR CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP THE STATE

OP CALIFORNIA

OPENING BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

. B ertram E dises,

Counsel for Petitioners.

R obert L . C ondon ,

Of Counsel.

A-t'C Cm f ^ 1

INDEX

Page

Opinions below .......................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................ 1

Statement of the case................................................. 2

Questions presented ................................................. 7

Argument .................................................................... 7

I. Introduction ............................................... 7

II. The picketing in the instant case was purely

an expression of speech, without any

“ non-speech” aspects, and hence is within

the area of communication of ideas pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments ....................................................... 8

III. Petitioners ’ motive for picketing was proper

and the picketing was not for an unlawful

objective ................................................... 10

A. The depressed condition of the

Negro people ............................... 10

B. The absence of any attempt to in

duce breach of contract.................. 14

C. The propriety of the demand for hir

ing Negroes in proportion to

patronage .................................... 16

IY. Peaceful picketing is not withdrawn from

constitutional protection because its ob

ject is deemed by the State Court to be

contrary to public policy, although not

violative of any statute............................ 20

V. The principles of the New Negro Alliance

case are applicable and should be con

trolling ....................................................... 23

Conclusion.................................................................... 25

T able of A u th o r ities C ited

Cases:

A. S. Beck Shoe Corp. v. V. Johnson, 153 Misc. 363,

274 N. Y. Supp. 946 ............................................... 14

American Fed. of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321....... 7

Anora Amusement Corp. v. Doe, 171 Misc. 279, 12

N. Y. Supp. (2d) 400............................................... 14

—4760

11 INDEX

Page

Bakery Wagon Drivers v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769......... 7

Bridges v. Calif., 314 U. S. 252................................... 22

Cafeteria Workers v. Angelos, 320 U. S. 293............ 8

Carlson v. Calif., 310 U. S. 106.................................. 7

Carpenters Union v. Ritter’s Cafe, 315 U. S. 722. ... 7

Craig v. Harvey, 331 U. S, 367.................................. 22

Duplex Printing Co. v. Deering, 254 U. S. 443........... 21, 22

Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., — IT. S. —, 69

Sup. Ct. 684 ......................................................... 7, 21, 22

Green v. Samuels on, 168 Md. 421 178 Atl. 109............. 14

Imperial Ice Co. v. Rossier, 18 Cal. (2d) 33, 112 P. 2d

631 ........................................................................... 15

James v. Marinship Corp., 25 Cal. (2d) 721.............. 19

Lifshitsv. Straughn, 261 App. Div. 757, 27 N. Y. Supp.

(2d) 193.............................................................. 14

Magill Bros. v. Building Service Union, 20 Cal. (2d)

506 ........................................................................... 8

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies,

312 U. S. 287 ............................................................ 7, 8

New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303

U. S. 552................................................................... 14,23

Quong Wing v. Kirkendall, 223 IT. S. 59.................... 19

Sewn v. Tile Layers Protective Union, 301 IT. S. 468. . 24

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 I . S. 1.................................. 11,19

Smith v. Allwright, 321 IT. S. 649............................... 11

Steele v. Louisville <fb Nashville R. Co., 323 IT. S. 192. . 11

Stevens v. West Philadelphia Youth Civic League,

34 Pa. D. & C., 612................................................... 14

Terminiello v. City Chicago, — IT. S. —•, 93 L. Ed.

(Adv. Op.) 865 ........................................................ 10,22

Texas Motion Picture & Vitaphone Operators Union

v. Galveston Motion Picture Operators Local, 132

S. W. (2d) 299 (Tex. Civ. App. 1939).................... 14

Thompsons. Moore Drydock Co., 27 Cal. (2d) 595. . . 19

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. 8. 88........................... 7

Turnstall v. Brotherhood of L. F. & E., 323 IT. S.

210 ........................................................................... 11

West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379......... 18

Williams v. International, etc., of Boilermakers, 27

Cal. (2d) 586 .......................................................... 19

Willis v. Local No. 106, 26 Ohio N.P. (N.S..) 435....... 19

INDEX 111

Statutes:

Executive Order No. 8802, June 25, 1941.

Executive Order No. 8823, July 18, 1941.

Executive Order No. 9111, March 25, 1942

First Amdt. to U. S. Const.......................

Fourteenth Amdt. to U. S. Const..............

Norris-LaGuardia Act .............................

Page

11

11

11

2.7

2.7

23

Miscellaneous:

Armstrong, “ Where Are We Going With Picketing”

36 Cal. L. Rev. 1 ...................................................... 8, 23

Dodd, “ Picketing & Free Speech, a Dissent” 56

Harv. L. Rev. 513 ................................................... 8

Fair Employment Practices Comm., First Report,

1943-44, Cha.pt. V ..................................................... 11

McWilliams, “ Race Discrimination and the Law,” 9

Science & Society, p. 1 ............................................. 11

Maslow, F.E.P.C., A Case History, 13 Univ. of Chi.

Law Rev. 407 .......................................................... 11

Myrda, “ An American Dilemma,” Chapt. 1 ............ 11

Restatement, Torts, Sec. 767...................................... 15

Restatement, Torts, Sec. 767-774 ............................... 16

Teller, “ Picketing & Free Speech,” 56 Harv. L. Rev.

180............................................................................. 8,9

Teller, ‘‘ Picketing & Free Speech, ’ ’ A Reply, 56 Harv.

L. Rev. 532................................................................ 8

S U P R E M E E O U R T OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1949

No. 61

JOHN HUGHES and LOUIS RICHARDSON,

Petitioners,

vs.

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFOR

NIA, IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF CONTRA

COSTA,

Respondent

OPENING BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of Califor

nia (R. 90) below is reported in 32 Cal. (2d) 850. The

opinion of the District Court of Appeal, First Appellate

District, Division One, State of California (R. 61) was not

officially reported but can be found in 82 A.C.A. 491,

186P(2d) 756.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of Cali

fornia was entered November 1, 1948, and rehearing was

2

denied November 29, 1948. Jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under § 28 U. S. Code Section 1257. The decision

below decided an important question of Constitutional law

involving freedom of expression and is a case “ where

any title, right, privilege, or immunity is specially set

up or claimed by either party under the Constitution . . .

of . . . the United States.”

The Federal question—whether the First and Fourteenth

Amendments guaranteed petitioners the right to engage in

peaceful picketing under the circumstances of this case—

was raised below as follows: (a) in the trial court (The

Superior Court of the State of California in and for the

County of Contra Costa) by petitioners’ opposition to the

preliminary injunction (R. 21-24) ; (b) in the trial court

at the time the judgments of contempt were entered, as

appears from the admissions and denials in the State of

California, District Court of Appeal (R. 40, 52); and (c) in

the California District Court of Appeal, by petitioners ’ peti

tion for writ of certiorari (R. 39, 40). The respondent was

the losing party in the District Court of Appeal, and peti

tioned the Supreme Court of California for a hearing,

which was granted. The Supreme Court decided the con

stitutional issue against petitioners, two judges dissenting

(R. 98-111). The issue wms again raised by Petition for

Rehearing (R. 112), which was denied (R. 120).

Statement of the Case

On May 20, 1947, Lucky Stores, Incorporated, herein

called Lucky, filed in the Superior Court of the State of

California, for the County of Contra. Costa, herein called

respondent, a verified complaint for injunction naming

various organizations and individuals as defendants (R.

1-18). So far as here material, the complaint alleged that

there existed a collective bargaining contract between

3

Lucky and Retail Clerks Union, Local No. 1179 (AFL),

under which the Union was the sole collective bargaining

agent for all its employees; a copy of which contract was

attached to the complaint (R. 8-18); that the contract pro

vided that Lucky employ only members of the union, unless

the union was unable to supply satisfactory employees,

in which event Lucky might employ non-union employees,

who, however, must join the union within a specified time

(R. 8-9); that the defendants demanded that Lucky “ agree

to hire Negro clerks, such hiring to be based upon the

proportion of white and Negro customers patronizing plain

tiff’s stores” (R. 4); that this demand was refused by

plaintiff (R. 4); that compliance with the demand would

violate the contract between Lucky and the union (R. 4);

that by reason of the refusal of Lucky to comply with their

demands, defendants picketed Lucky’s Canal Street Store

in the City of Richmond, State of California (R. 5) j1 that

unless this picketing were restrained Lucky would suffer

irreparable damage and be forced to close the store in

question (R. 5); that such picketing was an infringement

on Lucky’s right to do business and would require Lucky

to violate the contract with the union above mentioned (R.

6).2

On the same day, May 20, 1947, the above mentioned

Superior Court issued a Temporary Restraining Order,

restraining the defendants from, among other things, picket

ing Lucky Stores for the purpose of compelling Lucky to

engage in the selective hiring of Negro clerks in propor

tion to Negro customers (R. 35).

1 Lucky is a chain store with many retail outlets; this controversy

concerns only the Canal Street Store in Richmond, California.

2 The complaint and later the preliminary injunction also referred

to certain demands with respect to the arrest of an alleged shoplifter.

Since the picketing did not touch this question, both appellate courts be

low did not consider this aspect and it will not be dealt with herein.

4

On May 26, 1947, petitioners Richardson and Hnghes

filed counter-affidavits in support of a motion to dissolve

the temporary restraining order and to deny the preliminary

injunction (R. 26, 29). The affidavit of Richardson was in

substance as follows: That he was the president of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, Richmond Chapter, herein called NAACP, one of

the defendant organizations; that on May 17, 1947, he and

others had met with officials of Lucky, requesting it, among

other things, gradually to hire Negro clerks until the pro

portion of Negro to white clerks approximated the propor

tion of Negro and white customers; that he asked that such

increase in the proportion of Negro clerks take place as

white clerks quit or were transferred by Lucky; that he and

other members of the delegation explicitly stated that they

were not requesting the discharge of any of the present

employees of Lucky but were only requesting that vacancies

be filled with Negroes until the approximate proportion

was reached; that representatives of Lucky refused to dis

cuss the proposal and the discussion ended (R. 29-30) ; that

at the time of the discussion he had no knowledge of the

above mentioned contract between Lucky and the Clerks

Union; that the union had unemployed Negro members

and could supply qualified Negro clerks if Lucky requested

such help; that the NAACP had unemployed Negro members

who were qualified clerks and could supply such persons

to the Union and Lucky and that such NAACP members

would join the Union (R. 31) ; that picketing of Lucky’s

store took place on May 19, 1947, and continued until May

21, 1947, when the picketing ceased; that the picketing was

peaceful and without violence or misrepresentation of any

sort; that there were never more than six pickets patrolling

an area more than one hundred feet in extent; that the em

ployees and customers of Lucky had free ingress and egress

to and from the store without molestation; that the pickets

0

made no comments to customers or employees and the

placards they carried were truthful (E. 31). Eichardson.

also alleged that the NAACP had as its primary purpose

to promote the social and economic advancement of Negroes,

to assist them in finding employment and to encourage in

business and industry their full and fair employment;

that the NAACP had a number of unemployed members

in the area, including qualified Negro clerks; that the

NAACP was concerned with finding jobs for and prevent

ing discrimination against unemployed Neg*ro citizens;

that the NAACP had approximately 500 members, 98

per cent of whom were Negro (E. 29). The counter

affidavit of Hughes was similar to that of Eichardson (E.

26-28). Hughes alleged that approximately 50 per cent

of the customers at Lucky’s Canal Street store were Negroes

(E. 27).

On May 26, 1947, after a hearing on an Order to Show

Cause, the matter was submitted to the respondent Superior

Court on the complaint, counter-affidavits of Hughes and

Eichardson, points and authorities, and argument. No

affidavits were filed by Lucky, and the counter-affidavits of

Eichardson and Hughes are uncontroverted.3 The same

day, May 26, 1947, the court determined that Lucky was

entitled to a preliminary injunction (E. 34) and on June

5, 1947, issued its formal order granting the preliminary

injunction, restraining, among other acts, picketing to com

pel “ The selective hiring of Negro clerks, such hiring

to be based on the proportion of white and Negro cus

tomers” of Lucky (E. 35).

3 Lucky attempted to file certain affidavits in the District Court of Ap

peal, below, but was denied this right under state practice (R. 67-68).

The State Supreme Court did not pass on this question. These affidavits

are printed as part of the record herein (R. 45-50), but, as stated, the

appellate courts in California refused to consider them on the ground

that they were not properly before the court.

6

On June 21, 1947, citations were issued and served upon

petitioners ordering them to show cause why they should not

be punished for contempt for violating the preliminary

injunction. I t was stipulated between the parties that on

June 21, 1947, the two petitioners picketed the Canal Store

of Lucky carrying a placard reading: “ Lucky won’t hire

Negro clerks in proportion to Negro trade, don’t patro

nize.” (R. 38, 43). On June 23, 1947, petitioners moved

to vacate the preliminary injunction, which motion was

denied. The court found petitioners guilty of contempt

and adjudged that they be imprisoned for two days and

pay a fine of Twenty Dollars. A ten-day stay of execution

was granted (R. 35-36). On June 23, 1947 a petition for a

writ of certiorari was filed in the District Court of Appeal,

First District, Division One, State of California (R. 36-41).

The writ was granted (R. 41-43).

On November 20, 1947, the District Court of Appeal, all

three justices concurring, held that the preliminary injunc

tion was in excess of the jurisdiction of the trial court since

it violated petitioners ’ rights under the First and Four

teenth Amendments, and annulled the judgment of con

tempt (R. 61-83).

Respondent Superior Court thereafter petitioned the

Supreme Court of the State of California for hearing, which

petition was granted. On November 1, 1948, the California

Supreme Court reversed the decision of the District Court

of Appeal and affirmed the judgment of contempt (R. 90-

120). Four justices concurred in the majority opinion and

two justices dissented. On November 29, 1948 petition for

rehearing was denied, two justices dissenting (R. 120).

Certiorari was granted by this Court on May 2, 1949,

336 U. S. 966.

7

Questions Presented and Errors of the Supreme Court of

California Specified

The question before this Court is whether the California

Supreme Court erred in holding that peaceful picketing of

a retail store in a Negro neighborhood for the purpose of

inducing the operators of the store in the course of per

sonnel changes to hire Negro employees in proportion to

Negro customers, is not within the protection of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

ARGUMENT

I. Introduction

The Constitutional principles applicable in picketing

cases have been evolved by this Court in the dozen years

that have elapsed between the Serin4 case and the most

recent utterance of the Court on the subject, Giboney v.

Empire Storage and, Ice Co.,----- U. S. ------ , 69 Sup. Ct.

684. I t was the celebrated dictum of Mr. Justice Brandeis

in the Sewn case, which first intimated that picketing was

a form of free speech. The identification of picketing with

free speech became a holding of the Court in Thornhill

v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, Carlson v. California, 310 U. S.

106, and American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S.

321.

Following the Thornhill and Swing cases, various deci

sions have indicated that the constitutional right to picket

is not absolute and have pointed out some of the limitations.

Carpenters Union v. Ritter’s Cafe, 315 U. S. 722; Bakery

Wagon Drivers v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769; Milk Wagon Drivers’

Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 U. S. 287; Giboney v.

Empire Storage a/nd Ice Co., supra. Indeed, some com

mentators have expressed the view that the qualifications

4 Senn V. Tile Layers Protective Union, 301 U. S. 468.

8

on the right to picket have tended to obscure its Constitu

tional origin.5

Whatever may be the appropriate limits of the right to

picket, we earnestly believe that the instant ease presents

the strongest factual justification for constitutional protec

tion. of any picketing case considered by this Court since

the Thornhill decision in 1937. If the picketing here was

improper, it may well be necessary to revise the conception

that picketing can be sheltered by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments.

II. The Picketing in the Instant Case Was Purely An

Expression of Speech, Without Any “Non-Speech”

Aspects, and Hence Is Within the Area of Communi

cation of Ideas Protected by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments.

The decisions which have upheld the limitation of speech

in picketing cases have in all instances involved substantial

“ non-speech” elements. Thus the States have been per

mitted to enjoin picketing enmeshed with a pattern of

violence. Milk Wagon Drivers’ Union v. Meadowmoor

Dairies, 312 U. S. 287. In contrast, the picketing here was

admittedly peaceful, there was no obstruction of ingress or

egress, and Lucky’s customers and employees were not

hindered in any way (R. 28, 31).

The facts of the dispute herein were tersely but fully

stated in the placards carried by Petitioners. There were

no misstatements of fact or false representations. Cf.

Magill Bros. v. Building Service Union, 20 Cal. (2d) 506;

Cafeteria Workers v. Angelos, 320 U. S. 293.

The picketing was conducted at the point of dispute and

5 Armstrong, Where Are We Going With Picketing? 36 Cal. L. Rev.

1. See Teller, Picketing and Free Speech, 56 Harv. L. Rev. 180; Dodd,

Picketing and Free Speech: A Dissent, 56 Harv. L. Rev. 513; Teller,

Picketing and Free Speech: A Reply, 56 Harv. L. Rev. 532.

9

had no elements of secondary boycott. There was hence

no “ conscription of neutrals”, as in Ritter’s Cafe, supra,

315 U. S. 722.

Moreover, the pickets were representatives of small,

relatively weak citizens’ groups concerned with the promo

tion of the economic and social advancement of the Negro

people. The uncontroverted affidavit of the Petitioner

Richardson discloses . . . “ There are approximately

five hundred members of the Richmond Branch of the

NAACP, including a number of unemployed members.”

(R. 29).

Here was no strong labor union able to command sym

pathy and support from union members regardless of the

merit of the dispute. Truck drivers and other haulers of

supplies had no formal or tacit understanding, as sometimes

is the case in trade union disputes, to observe the picket

lines and cease deliveries. Petitioners lacked the united

strength, financial and otherwise, of thousands of dues

paying members to assist them in their efforts. (See

Teller, Picketing and Free Speech, 56 Harv. L. Rev. 180,

201, quoted by Justice Traynor in his dissent below).

There was no “ powerful transportation combination” ,

with “ patrolling, and . . . formation of a picket line

warning union men not to cross at the peril of their union

membership”, adverted to by Mr. Justice Black in the

Giboney decision, supra, ----- U. S. -——, 69 Sup. Ct. 684,

as one of the reasons for upholding the injunction in that

case.

On the contrary, all that the Petitioners did was to publi

cize their grievance against Lucky for the brief space of

a few hours by means of placards. Petitioners doubtless

could have used newspapers or handbills to inform the

public of their dispute, in which event the picketing aspect

would have been absent and there would probably have

been no injunction. But as they are here in forma pauperis.

1 0

it is understandable that they chose to use placards, which

are par excellence the poor man’s means of publicizing

grievances. Petitioners, and others in such situations,

should not be afforded any lesser degree of constitutional

immunity than those who are able to employ the traditional

means of communication. Terminiello v. City of Chicago,

-----U. S .------ , 93 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 865.

III. Petitioners’ Motive for Picketing Was Proper and

the Picketing Was Not for an “Unlawful Ob

jective.

A. The Depressed Condition of the Negro People.

Assuming, without conceding, that the extension to peace

ful picketing of constitutional sanction depends upon the

motives of the picketers, we submit that a demand for the

hiring of Negroes in proportion to their patronage is not

unlawful, and that picketing in support of such a demand

is directed to a lawful objective. Properly to evaluate the

justification of the demand requires some understanding

of the economic difficulties faced by the Negro in the United

States.

In his dissenting opinion below (E. 106), Justice Carter

stated:

“ It must be admitted by every thinking person that

Negroes are, and have been, constantly discriminated

against. They are considered by some people as being fit

for only the most menial positions. It was even found

necessary for the Legislature of the various states to pass

laws that they might obtain shelter and food on an equal

basis with members of the white race. The abolition of

slavery did not free the Negro from the chains his color

imposes on him.”

Justice Carter’s observations are borne out by numerous

sociological treatises on the subordinate role in the economy

1 1

to which the Negro has been condemned since Emancipa

tion.6 The files and reports of the President’s Fair Employ

ment Practices Committee show a depressing picture of the

economic discrimination that has confronted the Negro at

tempting to find employment. They show beyond cavil that

the Negro for the most part finds employment opportunities

only in the most menial capacities, and that he is invariably

“ the last to be hired and the first to be fired,” 7

This Court has had frequent occasion to note the obstacles

thrown in the path of the Negro people in their struggle

against economic discrimination.8 The Court has not

merely noted such discrimination: it has stood as a firm

champion of the oppressed Negro people. As Justice

Murphy stated in Steele v. Louisville £ Nashville R. Co.,

323 U. S .192:

“ The Constitution voices its disapproval whenever

economic discrimination is applied under authority of

law against any race, creed or color. A sound democ

racy cannot allow such discrimination to go unchal

lenged.

“ Racism is far too virulent today to permit the

slightest refusal, in the light of a Constitution that

6 No attempt will be made to collect this data herein, but the Court’s

attention is directed to Myrdal, An American Dilemma, Chapter 1;

McWilliams, Race Discrimination and the Daw, 9 Science & Society, p. 1;

Murray, Right of Equal Opportunity in Employment, 33 California Law

Rev. 388.

7 See the First Report of the Fair Employment Practices Committee,

1943-1944, Chapter V and tables. The Fair Employment Practices

Committee, generally known as the F.E.P.C., was established by Executive

Order No. 8802 on June 25, 1941. Its powers were further defined by

Exec. Orders No. 8823, July 18, 1941 and No. 9111, March 25, 1942. See

Maslow, FEPG—A Case History, 13 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev. 407.

See also To Secure These Rights, Report of President’s Committee on

Civil Rights, 1947.

■ 8 See, for example, Smith v . Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; Tunstall V. Brother

hood of L. F. <& E., 323 U. S. 210; Shelly v . Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

12

abhors it, to expose and condemn it whenever it ap

pears in the course of a statutory interpretation.”

The Negro people’s struggle for equality is made more

difficult by the varied forms which discrimination takes. It

may consist of an openly acknowledged exclusion of Negroes

from membership in a social or professional organization.

Or, on the other hand, such exclusion may be accompanied

by denial of a discriminatory policy. Discrimination may

be enforced through the medium of segregation, which re

sults in unequal facilities for the Negro minority in edu

cation, travel, and in many other activities. It may take

the form of “ quotas,” by which arbitrary limits are set

on the participation of Negroes in many of the pursuits es

sential to a full life. Whatever the form, the effect on the

Negro members of the community is the same: the denial of

the right to be judged, and to participate fully in the mani

fold activities of American life, on the basis of individual

merit rather than on the basis of skin coloration.

It is in the field of employment opportunities that the

virus of race discrimination has its most destructive effects,

on the Negro people and the nation as a whole.9 While

the goal of equal opportunity in employment for Negroes

has become part of our national public policy, candor re

quires the admission that very little has been done to imple

ment the goal, as witness the unhappy fate of Fair Employ

ment Practices legislation in Congress. Nevertheless, eco

nomic equality for the Negro must continue to be sought

through every possible means, not only because justice and

reason require it, but because, as is widely recognized, the

existence in our nation of a large, depressed economic group

is incompatible with the healthy functioning of our economic

system.

9 “To Secure These Rights”, Sec. II, Subdivision 4, Report of the Presi

dent’s Committee on Civil Rights, 1947.

13

Faced with discrimination in every phase of their strug

gle for livelihood, the Negro people' have learned that their

problems cannot be solved by mere wishing, or by denuncia

tions of discrimination in general. Experience has taught

them that progress is made by the application of their

energies, together with those of others who are in accord

with their aims, to the correction of specific evils. The

means adopted to meet the problems of discrimination in

employment may be national, state-wide, or local in scope.

They may take the form of encouraging remedial legisla

tion. They may be expressed in fund-raising efforts to pro

vide for the higher education of Negro youth. They may

involve community-wide educational campaigns. They may

take the form of court action, as in the restrictive covenant

suits. Or they may take the form which the Petitioners

adopted in the present case: negotiations with a business

establishment in an effort to obtain jobs for Negro people

and protest through peaceful picketing when the officials

of the establishment refuse to give fair consideration to the

problem.

It cannot be argued that the organizations Petitioners

represented did not have a legitimate economic interest to

advance. Their members, some of them qualified clerks,

were unemployed. They attempted, by negotiation, to win

employment for their members at a store where their appeal

could be effective because of the substantial Negro composi

tion of the neighborhood. They sought not the discharge

of any one then employed, but only a share of future vacan

cies. It is submitted that when Lucky summarily rejected

their requests, they were entitled to make the facts known

to Lucky’s customers by the method of peaceful picketing.

Nor is the foregoing conclusion altered by the fact that

Petitioners were acting on behalf of a racial group rather

than in connection with a purely trade union dispute. Pick-

14

eting, as protected free speech, cannot be limited to trade

unions. Indeed, the implication of New Negro Alliance v.

Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U. 8. 552, is that the right of

Negroes to seek to enhance their employment opportunities

may be more substantial than the rights of union members,

since the discrimination against Negroes is so much greater.

State Courts have sometimes afforded protection to racial

pickets (Lifshitz v. Strau.ghn, 261 App. Div. 757, 27 N. Y.

Supp. (2d) 193; Anora Amusement Corp. v. Doe, 171 Mi sc.

279, 12 N. Y. Supp. (2d) 400; Stevens v. West Philadelphia

Youth Civic League, 34 Pa. D. & C. 612) and sometimes have

enjoined such picketing (A. S. Beck Shoe Corp. v. V. Johnson,

153 Misc. 363, 274 N. Y. Supp. 946; Green v. Samuelson,

168 Md. 421, 178 Atl. 109; Texas Motion Picture and Vita-

phone Operators Union v. Galveston Motion Picture Oper

ators Local, 132 S. W. (2d) 299 (Tex. Civ. App. 1939)).

Both the Green and Beck cases were decided before the Semi

case; neither case discussed the applicability of the First

and Fourteenth Amendements.

We submit that in the light of the considerations dis

cussed above, Petitioners’ demand for jobs for Negroes,

far from having an “ Unlawful objective,” was calculated

to alleviate a tremendous social evil and was in furtherance

of one of the highest aims of American democracy—equality

of economic opportunity for all, regardless of race or color.

B. The Absence of Any Attempt To Induce Breach of

Contract.

Lucky’s original complaint was based primarily on the

theory that the defendants were attempting to induce a

breach of contract between Lucky and the Retail Clerks

Union. Neither Lucky nor respondent pressed the hy

pothesis very strongly in the Appellate Courts of California

and presumably have abandoned it. Nevertheless, on the

15

strength of the possibility the respondents may revive the

contention, we shall quote the effective answer given by

Justice Peters in the District Court of Appeal (R. 68-70),

as follows:

“ In the first place, there are no facts pleaded that demon

strate that petitioners’ actions in picketing to secure the

proportional hiring of Negro clerks wTould necessarily re

sult in a breach of contract between the union and Lucky

Stores. The picketing Negroes did not demand the dis

charge of any existing employees, except the employee who

had fired the shot in arresting Jackson, and the picketing

was not directed at this last-mentioned objective. The de

mand was that, as. white help quit or was transferred, they

be replaced with Negroes. The evidence shows that the

union is willing to accept Negro clerks, and that, in fact,

at all times here pertinent, it had qualified Negro clerks in

the union who were unemployed.

“ In the second place, and this is a complete answer to

this contention, while it is now the law of California that,

under certain circumstances, a deliberate and intentional

interference with an existing contract is tortious and ac

tionable (Imperial Ice Co. v. Rossier, 18 Cal. (2d) 33 (112 P.

2d 631)), it is clearly the law that such interference may,

in a proper case, be justified and therefore privileged. The

Rossier case expressly recognizes that justification may

exist for such an interference with the contract rights of

others. It is there stated (18 Cal. 2d at p. 35) ‘Such justi

fication exists when a person induces a breach of contract

to protect an interest that has greater social value than

insuring the stability of the contract. (Rest. Torts, § 767.)

Thus, a person is justified in inducing the breach of a con

tract, the enforcement of which would be injurious to health,

safety, or good morals. (Citing two cases and the Restate

ment of Torts, § 767 (d).) The interest of labor in improv-

16

mg working conditions is of sufficient social importance to

justify peaceful labor tactics otherwise lawful, though they

have the effect of inducing breaches of contracts between

employer and employee or employer and customer. (Citing

many cases.) In numerous other situations justification

exists (see Rest. Torts, secs. 766 to 774), depending upon

the importance of the interest protected.’ It should be

noted that in the comment on clause (d) of section 767 of the

Restatement of Torts, cited supra, which is the section that

enumerates the interests that create the privilege, it is

stated that attempts to prevent racial discrimination come

within the privilege. That this is so would seem quite clear.

The economic interest of Negroes in securing employment

for members of their race, and in attempting to alleviate

the results of a discriminatory employment policy, are of

sufficient social importance to justify the interference with

the type of contract here involved.”

We submit that no more need be said regarding Peti

tioners ’ alleged attempt to induce breach of contract.

C. Propriety of the Demand for Hiring Negroes in Pro

portion to Patronage.

The Court below assumed that the demand of Petitioners

for “ proportionate” hiring had as its objective “ The dis

criminatory hiring of a fixed proportion of Negroes, regard

less of all other considerations” (R. 91) (emphasis

added). This assumption that Petitioners demanded dis

crimination in favor of Negroes is gratuitous and ignores

the most important considerations presented by the record.

The store in question was located in a Negro neighbor

hood with 50 per cent of the customers being Negroes. Quali

fied Negro Clerks—members of the Retail Clerks Union—

were available for employment. Yet there is no contention

17

that Lucky hired Negro clerks in numbers even approxi

mating its Negro trade. Indeed, the record does not show

that Lucky hired any Negro clerks at all.

If there is no discrimination against Negroes, one would

expect to find them gainfully employed in various pursuits

in approximately the same proportion that their population

bears to the nation as a whole. Certainly, one would expect

Negroes to be employed as salespersons in shops in the

areas where they lived.

Whether or not one agrees with the wisdom of the de

mand, it certainly cannot be deemed unreasonable to re

quest that a retail store employ Negro clerks in numbers

roughly approximating the proportion of the store’s Negro

trade. Indeed, since Negroes are consistently excluded from

many types of employment, an allocation of jobs on a pro

portionate basis means in practice an increase in the num

ber of jobs available to Negroes and the alleviation of the

existing condition of discrimination.

In his dissent below, Justice Carter correctly analyzed

the objective of Petitioners when he stated, (B. 105-106)

“ Petitioners are seeking nondiscrimination, not discrimina

tion. Discrimination is treatment which is not equal. It

follows that nondiscrimination must be equal treatment.

Petitioners are seeking just that, and nothing more. It has

long been established in equity, that the court will look

through form to substance. I t has also been said often and

emphatically that in equity each case must be decided on its

own facts, hence it might logically follow that in a neigh

borhood predominately Chinese or Japanese, or on an In

dian reservation that picketing for a proportional hiring

of members of the particular race involved would be just,

equitable and entirely in accord with sound public policy.

It is not involved here. But involved here is a store situ

ated in a district where the population is composed of a

18

large majority of members of the Negro race. These mem

bers of the Negro race comprise at least 50 per cent of the

customers of the store in question. The Petitioners by

means of peaceful picketing and through the words printed

on their placards were seeking to publicize their grievance to

members of their race, and to members of the white race in

sympathy with their long struggle for freedom, so that eco

nomic pressure might be exerted to gain for them equality

in the labor field. They requested only that a proportionate

number of Negro clerks be hired as replacements where

necessary. Not that any white person be fired that they

might be hired . . . It has been said that Negroes may obtain

equal opportunities with others for employment by organi

zation, public meetings, propaganda and by personal soli

citation. The effectiveness of these methods may well be

doubted. Labor, as a whole, found that the only way it

might attain its objectives of better working conditions,

hours and pay was to exert economic pressure on employers.

Nothing else was heeded. Is the Negro here to be denied his

only effective means of communicating to the public the facts

in connection with the discrimination against him, and the

only effective method by which he may achieve nondiscrimi

nation?”

Moreover, Petitioners’ conduct was not unlawful even

if it be assumed that they were seeking preferential treat

ment, that is, that they wanted more jobs for Negroes as

clerks than would have been the case if Lucky had followed

a non-discriminatory hiring policy. Equity, as Justice

Carter pointed out, supra, is concerned with substance

rather than form. Special consideration does not become

“ discrimination” where its beneficiaries are a uniquely op

pressed and exploited social group, such as women and

children before the advent of minimum wage legislation.

See West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379, 394-395.

19

To characterize the quest of Negroes for equal job oppor

tunities as “ discrimination” against whites is to invoke the

“ fictitious equality” which this Court condemned in Quong

Wing v. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59, 63, and again in the Par

rish case, svipra. Only if the shoe were on the other foot,

and the dominant white group sought further to depress the

Negro, would the concept of “ discrimination” become re

levant and meaningful. See Willis v. Local No. 106, 26

Ohio N. P. (N. S.) 435; compare Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.

S. 1.

The California Supreme Court, in its majority holding

reversing the unanimous decision of the District Court of

Appeal relied on James v. Marinship Corp., 25 Cal. (2d)

721, and two related California cases, Williams v. Interna

tional etc. of Boilermakers, 27 Cal. (2d) 586 and Thompson

v. Moore Drydock Co., 27 Cal. (2d) 595. In the Marinship

case a Union had a closed shop agreement with an employer,

providing that only members of the Union could be em

ployed. The Union did not admit Negroes to full member

ship ; they were required to pay union dues but were segre

gated into separate lodges with fewer privileges than white

members. Under these circumstances, the Court held that

public policy forbade both a closed shop and a closed union.

The Williams and Thompson cases held similarly.

Declaring that “ race and color are inherent qualities

which no degree of striving or of other qualifications for a

particular job could meet, those persons who are born with

such qualities constitute, among themselves, a closed union

which others cannot join” (R. 96), the court below con

cluded that the instant situation was controlled by the Marin

ship decision.

With due respect to the California Supreme Court, whose

original decision in the Marinship case marked an epochal

advance in the struggle of the Negro people against dis-

2 0

crimination, it is impossible to follow the logic which equates

the Negro race with a “ closed union” . The latter remains

“ closed” because of the voluntary action of its membership.

If the public interest so requires it can be forced to open its

ranks to persons of all races and colors. Should it decline to

eliminate racial discrimination by action fully within its

control, it is not unfair to deny judicial protection to its

contractually established job monopoly.

The Negro people are in an entirely different category, if

their ranks are “ closed” to non-Negroes, it is not because

of choice but through the happenstance of birth. As Justice

Traynor pointed out in his dissenting opinion below, the

Negro people is a group “ helpless to open its ranks to all”

(R. 108). Indeed, it may legitimately be doubted whether

there are many who seek the privilege of incorporation into

the racial ranks of Negro, since that “ privilege” is accom

panied by political, social and economic disenfranchise

ment. To compare such “ exclusiveness” with that of a

union having a deliberate policy of racial discrimination,

is to play with words and ignore realities.

IV. Peaceful Picketing Is Not Withdrawn from Constitu

tional Protection Because Its Object Is Deemed by

the State Court to Be Contrary to Public Policy,

Although Not Violative of Any Statute.

We have previously stated our belief that the court below

erred in concluding that the picketing was for an “ unlawful

purpose.” The question arises, however, as to whether pe

titioners had a constitutional right to picket even if the

purpose was “ unlawful” , in the sense in which the lowrer

court used the term. It must be noted that there is here no

question of violating any law—federal, state or municipal.

The “ illegality” , if such it be, resulted from the California

21

Supreme Court’s own conception of public policy, unaided

by legislative determination.

Consequently, the instant case is sharply distinguishable

from such decisions as Carpenters <& Joiners Union v. Rit

ter’s Cafe, 315 U. S. 722, and Giboney v. Empire Storage &

Ice Company, — IT. S. —, 69 S. Ct. 684,, where the picketing

was in direct opposition to valid state legislative enact

ments. In the instant case the picketing was not only en

tirely peaceful, but it violated no law except the judge-made

law formulated after the event.

The question is thus raised of whether a State court can,

by resorting to its own conception of what constitutes an

illegal purpose, define and circumscribe the area in which the

constitutional guarantee of free speech shall operate.

It is, of course, obvious that different States may, and in

fact do, have different conceptions of public policy. In

some areas of the nation, particularly those areas charac

terized by separate schools for colored and white children,

segregated transportation, laws against miscegenation, etc.,

picketing for equal rights for Negroes may well be deemed

subversive of public policy. In other States, such as Cali

fornia, such picketing would in all probability be held to be

for a lawful objective. Numerous other widely differing

conceptions of public policy may readily be imagined. It

would, we submit, lead to an intolerable situation if the fun

damental right of free speech, unadulterated by extraneous

elements of a non-speech character, were made to depend on

the varying social concepts of the different judges who make

up the courts of last resort in the forty-eight States of the

Union. An acceptance of such an interpretation will in

volve an abdication by this Court of its position as ulti

mate interpreter of the Constitution.

We think that the controlling principle is that enunciated

by Justice Brandeis in Duplex Printing Company v. Peering,

22

254 U. S. 443, 488, which was quoted with approval by this

Court in its latest decision on picketing, Giboney v. Empire

Storage and Ice Company, — U. S. —, 69 S. Ct. 684:

“ The conditions developed in industry may be such

that those engaged in it cannot continue their struggle

without danger to the community. But it is not for

judges to determine whether such conditions exist, nor

is it their function to set the limits of permissible con

test and to declare the duties which the new situation

demands. This is the function of the legislature which,

while limiting individual and group rights of aggres

sion and defense, may substitute processes of justice

for the more primitive method of trial by combat (italics

added).”

In view of the circumstances of the picketing in the pre

sent case—its entirely peaceful character, the complete ab

sence of threats or violence or other non-speech elements,

the reliance on nothing except an appeal to the reason and

sympathies of the public, without even an appeal to organ

ized labor which might have enhanced the persuasive power

of the picketing, and the fact that the Petitioners’ conduct

violated no positive law—we submit that the proper test of

whether the picketing trranscended the bounds of legality

was that of “ clear and present danger” rather than that

of “ unlawful objective” . Terminiello v. Chicago, — TJ. S.

—, 93 L. Ed. (Ad. Op.) 865; Bridges v. California, 314

U. S. 252; Craig v. Harvey, 331 TJ. S 367.

Clearly, peaceful, non-violent picketing by two individuals

for a few hours, for the purpose of persuading a large em

ployer to hire some Negro personnel, is not “ likely to pro

duce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive

evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance,

or unrest. ” Terminiello v. Chicago, supra, 93 L. Ed. (Adv.

Op.) at 868. Even had the objective been accomplished, and

Lucky thereby been induced to contribute slightly toward

23

the reduction of the disproportionately high incidence of

Negro unemployment in the State of California, the result

would not endanger the peace and welfare of the people of

the State.

The restrictive decision of the court below signifies, we

believe, a trend on the part of the State courts toward re

jection of this Court’s decisions establishing peaceful pick

eting as an exercise of free speech. See e. g., Armstrong:

“ Where Are We Going with Picketing” 36 Calif. L. Rev. 1.

Unless this trend is reversed by a clear statement by this

Court of the extent to which peaceful picketing is immune

from state judicial action, labor and the nation may again

be subjected to the evil of “ government by injunction” .

This case presents an opportunity to put a stop to this dan

gerous trend.

V. The Principles of the New Negro Alliance Case Are

Applicable and Should Be Controlling

The State Supreme Court, pointing out that New Negro

Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., 303 U. S. 552, was con

cerned with the question “ whether the case made by the

pleading involves or grows out of a labor dispute within the

meaning of Section 13 of the Norris-LaGuardia Act” , con

cluded that the case did not involve “ any controlling con

stitutional principle ’ ’, and that it provided no precedent of

value” in resolving any of the issues of the instant case (R.

96). In other words, the Court below was of the view that

the issue in the New Negro Alliance case was entirely pro

cedural and that no questions of substantive law were in

volved.

We do not understand that the New Negro Alliance case

can be so limited. The legality of picketing cannot be de

termined solely by the presence or absence of anti-injunction

statutes, State or Federal. It is no longer open to question

24

that the right of peaceful picketing is protected by the First

Amendment and that the right may be exercised “ without

special statutory authorization by a state.” Senn v. Tile

Layers Protective Organisation, 301 U. S. 468. New Negro

Alliance seems to us to stand for the broad proposition

that Negroes and their organizations have a legitimate

economic interest in the question of the employment of

Negroes, and that peaceful picketing is an appropriate

means of communicating to the public their grievances con

cerning this question.

The striking factual similarity of the New Negro Alliance

case and the instant case is apparent from the following re

cital, taken from the opinion of this Court (303 U. S. at

559) :

“ The case, then, as it stood for judgment, was this: The

petitioners requested the respondent to adopt a policy of

employing Negro clerks in certain of its stores in the course

of personnel changes; the respondent ignored the request

and the petitioners caused one person to patrol in front

of one of the respondent’s stores on one day carrying a plac

ard Avhich said: ‘Do Your Part! Buy Where You Can Work!

No Negroes Employed Here!’ and caused or threatened a

similar patrol of two other stores of respondent. The in

formation borne by the placard was true. The patrolling

did not coerce or intimidate respondent’s customers; did

not physically obstruct, interfere with, or harass persons

desiring to enter the store, the picket acted in an orderly

manner, and his conduct did not cause crowds to gather in

front of the store.”

After deciding that the case involved a “ labor dispute”

within the meaning of the Norris-LaGfuardia Act, the Court

declared:

25

“ The desire for fair and equitable conditions of employ

ment on the part of persons of any race, color, or persuasion,

and the removal of discrimination against them by reason

of their race or religious beliefs is quite as important to

those concerned as fairness and equity in terms and condi

tions of employment can be to trade or craft unions or any

form of labor organization or association. Race discrimina

tion by an employer may reasonably be deemed more un

fair and less excusable than discrimination against workers

on the ground of union affiliations. There is no justification

in the apparent purposes or the express terms of the Act

for limiting its definitions of labor disputes and cases

arising therefrom by excluding those which arise with

respect to discrimination in terms and conditions of em

ployment based upon differences of race and color.”

Thus, the opinion demonstrates the belief of this Court

that picketing to rectify racial discrimination is every whit

as socially justifiable and important as labor picketing,

which is constitutionally protected. The inference is ir

resistible that this Court regards the former type of picket

ing as equally within the constitutional guarantee.

Conclusion

This case is concerned with the concrete application of

certain generally accepted abstractions. Thus, it can hardly

be denied that the Negro people have been victims of

economic discrimination. Most persons would also agree

that they are entitled to seek to overcome this discrimina

tion and obtain economic equality.10 Had Petitioners

charged Lucky with discriminating against Negroes in hir

ing clerks and demanded that such discrimination cease,

an injunction doubtless would not have issued. (See

majority opinion in the State Supreme Court, R. 95).

10 See Green v. Samuelson, 168 Md. 421.

26

Here, however, Petitioners went a step further. They

sought not merely equality to compete on the open market

for jobs, an equality shown by experience to be of dubious

value to Negroes, but they requested that a definite per

centage of Negroes be hired as vacancies occurred. We sub

mit that the valuable right of peaceful picketing should

not be made to depend on the distinction between a general

demand for the ending of discrimination, and a concrete

demand for a number of jobs roughly proportionate to

Negro patronage.

A reversal of the decision below will help to stem the

growing trend of the state courts toward curbing free

speech deemed in conflict with the courts’ own conceptions

of public policy, which differ widely from state to state;

will enlarge the scope of effective action by Negroes in

their fight to equality of economic opportunity; and will

add another to the notable list of decisions of this Court

which have aided the Negro people in their attempts to

attain full citizenship.

Dated at Oakland, California, October 14, 1949.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n H u g hes and Louis R ichardson ,

Petitioners,

By B ertram E dises,

Counsel for Petitioners,

1440 Broadway,

Oakland, California.

R obert L. C ondon,

Martinez, California,

Of Counsel.

(4760)

> A y . A ' A v . ' ? y r . v .• ■

-• • J., - • • • • •- ■ v ■ ■' •' • . '

' a a , ' A

*: v y

-

■ A

y-A-'X

’

: <■

-

. ' ' A v i y ■ ' y - A J i 4

A , ’ A C i. K JS A A ' ■■V'At

{ A ; ' t ■

Wm

i.A,'-

:

■ -A A ■ • rA . ' 1 ■' 3 -

V. -■ , • A ; A Aa - A a A

%. \ f ' s 'yt : • ..... .

‘

.

i' ^

r ' / '

,?A.

• S’ -• ' • _ .

x . v x a \ y ~ a . '

m

. . x-; - y /-’ yiAS? .•> Am i . AwmA*..-.,, m pi h i

aVa- •■: - I* - .-A Â AJ- - #- .••• y^A ,..

■

A .;

->■■■ ' ■ • ... ' <j -

" > A A

■' ■■ v ; V 'v

5 1

^ >A r . / f V ̂■ A X' ;. ;** .*vyA j > V ' “ *

'

X a- . . : x x x ; x x - x -v, '• a X x V x

■■ y . y : >. - - A - ■

y "■ v : a.: - / -' a X C - \ .:h v:- -X ' X v X X ’V 'X - ■'■ a "' '' ''•r;'r '"”''

XO-XX

A :

A • y ' ; A ; 1

*

A ” Av -jr' i - , ,- - / ;

A ifA : ' ; v a ;yA;̂ :/yyyy'A

> ' : >: '■ %

.

v y

■ ■ v ; •

\ s a ^

..

■ -.V ' ;■■ . ' .y,.. *■'■■■..-. ’ !

.

A . - i ,

■v' \ A i '. - • r: A' -r

a ; S

V ' - r< l/ / -y; ', s . ' ■ ' A A

' • - - '. J- ■ v:

t m -A;', a A' * M

;V

> '■ ' A / . . A ; : A : A - : A

v „ ,

_ ............

. i .

. •.■ A v f'*-. Vtf-'• a.■-A.:■ ■ ■:,a v , ;-■ -y ̂

■ / V-A am;

* - r ; W ' V‘ "

. . • ; ( ■' y

■yyA;

A

,■

■

my<;xih ;

>;ii '.''y -yV

,A A -yAVyfe / -y y y ' y y / s - y A y " I

■■ " '■• ■ ' . .y .y- f X .i 1 , > <

■; f e - y ' ̂ j A : ; k ? :

"■■ ' A : - : ' - ; , % yA-A. y' ' V1

> ..•- - ■.

' y >

yy-A-.-vv,' m ■

> a a v • ' ; X C * /

- ■ M ; ■STA

' V -Vy

■,■ y v j * --.•y- y

' ...... H M i l l R i

' : r y , ' . ■ A ■ y

■• ■ A :A y :.y - , - '■ ; ' , A , . A : : . y , : :'rK-l

y '• > , y A ^ ■ y V K

MMMMjM'.' ' :AAyA yggH

- 3 v . - ■ .:

: ' - v ' ' ' y . .. , ' - ^ ' A '

' y •-: r A V y ' •. , ■ y ■ \ , V y *■■ . y ■'

' y. y y../ " . . . J . - '< , - , - • / ' ; y y " - ■

: : y - A u. . . . . . . . . " ; y . . '

■:..A A:.'.

- - ~ ; x .

-

y A '

X . - ■ A-Af

; ' ■ Aa

- -

•

y -a

y AAA

;;,.y A

A y '■ X f

X ’ - A

y.-'V';

■-

A . A .

X " .

jfr'i

:: h

..'At

,\ ' ■A:

: A:?A...V y '- 'y f K S y A' : . A y i . ... •" y ;

' ■:,vrAy ■ * y y .y y - y ’i . t '

" " I 3 S ■ - ' -■

A i

■A .

:

'• A 1 i / -y ■ • ■ • . y • 1 - ■ •• • • ’ • y\ ...

.

A.'-:'y : y/VAA A

. y ■ - . a . v x ,

- ' , ■ - w , ■ y A / . . . . : A y

■ • ' : - ■•■■; A ■ ■.-/- . . . . . ■.. .. .- y, . . ' ■ ■ ■ ■"■•; . . . :. •• i yy.'}.a- yy

A t . :

: A - ‘ A ; ; : j y , * 3 y

• yy' ■'... :; •■■ '<■ y. ,

A / A : '-‘ A '. A t . . . A y y t ■■■■■'

y ; A A y .: A _ H , ,■ • ’ y - - A y . y

■X) 'y- b r t A * , J , (S , A 'm£r A ■ A y / . ■ A A f 'A ..

A

V '•> ........... :

' v '-

m . - a

:*Ay • -

.