Garrison v. Keeten Brief for Petitioners-Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 15, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garrison v. Keeten Brief for Petitioners-Appellees, 1984. 3621e8d9-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77071039-dfea-4c99-acde-4c5634bcc2eb/garrison-v-keeten-brief-for-petitioners-appellees. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

d

*•1

>

«

5 t\ l V\ O c \ r \ r < S o ' /

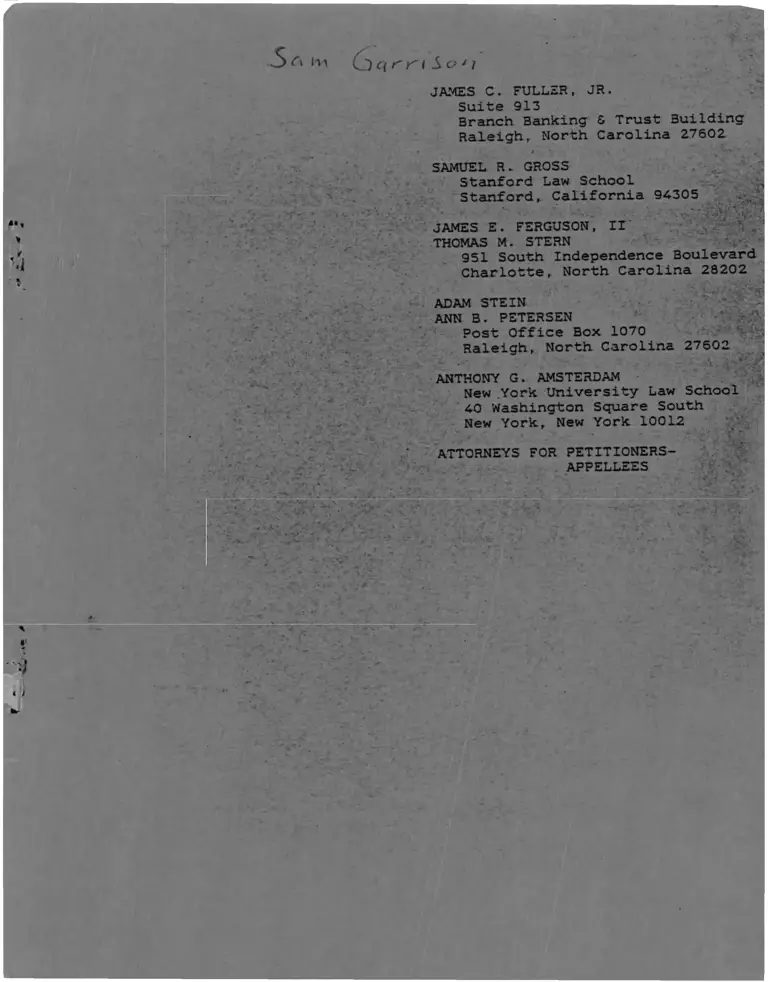

JAMES C. FULLER, JR.

Suite 913Branch Banking S Trust Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

SAMUEL R. GROSSStanford Law School

Stanford, California 94305

JAMES E. FERGUSON, II

THOMAS M. STERN951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

ADAM STEIN

ANN B . PETERSEN

Post Office Box 1070

Raleigh, North Carolina

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAMNew York University Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITI0NERS- APPELLEES

27602

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR Rr,VIc.A? ....

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...........................

Introduction ..........................

Legal Background ......................

Procedural History Of These Cases .....

STATEMENT OF FACTS ..............................

Death-Qualification And Juror

Attitudes ........................

Death-Qualification And Juror

3ehavior .........................

The Process of Death—Qualification ....

ARGUMENT: PART ONE -- THE COMMON ISSUES ........

I. The District Court Correctly Held That

The State’s Use Of Death-Qualification

Procedures To Exclude Impartial Jurors

At The Guilt-Or-Innocence Phase Of

Petitioners' Capital Trials Denied Their

Sixth And Fourteenth Amendment Rights

To Fair And Impartial Juries ..........

A. The District Court's Findings On

Conviction-Proneness ..............

3. The Applicable Standard Of Review

Of Those Findings .................

C. The Controlling Legal Principles....

D. The State's Arguments For Reversal..

(i) Petitioners' Standing ........

(ii) The Impartiality Of Death-

Qualified Jurors .............

(iii) The Possibility Of Partiality

On Guilt -- The "Nullification"

Argument .....................

Page

1

3

3

6

8

8

8

10

13

lk

lk

lk

16

18

22

23

25

29

i

Page

*

«

■

(iv) The Value Of The Social

Science Evidence .................

a. Attitudes and Behavior .......

b. Simulated Jury Research ......

(v) The Constitutional Significance

Of The Biasing Effects Of

Death-Qualification ..............

a. The Significance Of The

Applebaum Affidavits..........

b. The Legal Question At Issue ...

II. The District Court Correctly Held That Death-

Qualification Procedures Denied Petitioners'

Sixth And Fourteenth Amendment Rights To

Juries Selected From A Representative Cross-

Section Of The Community ....................

ARGUMENT: PART TWO — WILLIAMS' SEPARATE CLAIMS.....

I. The Biasing Effect Of The Jury Selection

Procedures Is Unacceptable When The

Defendant Is Sentenced To Die .............. -

II. A Juror Who Insists That She Is "Not

Sure" And "Not Positive" That She Could

Recommend The Death Penalty Is Not

Irrevocably Committed To Vote Against

Death So As To Permit Her To Be Excused

For Cause From The Venire ..................

CONCLUSION .........................................

34

34

36

40

40

45

50

55

55

57

65

APPENDIX Summary Of The Studies Introduced In^o

Evidence By Petitioners............... la

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38 (1980) .............. 20,32,46,58

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946).... 26

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978) .......... 12,45,47,53

Barfield v. Harris, 719 F.2d 58 (4th Cir. 1983)... 63

Barfield v. Harris, 540 F.Supp. 451

(E.D.N.C. 1982) ........................... 48,64

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980) ............ 29,55

Blankenship v. State, 280 S.E.2d 623 (Ga. 1981) •• 64

Bonds v. Mortensen & Lange, 717 F.2d 123

(4th 1983) ................................. 17

Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742 (1970)...... 56

B's Company, Inc. v. B.P. Barker & Assoc.,

391 F. 2d 130 (4th Cir. 1968)................ . 18

Bumper v. North Carolina, 391 U.S. 543 (1968)....

Canron Inc. v. Plasser American Corp., ,7

609 F.2d 1075 (4th Cir. 1979) ..............

Chandler v. State, 442 So.2d 171 (Fla. 1983)..... 64

Connally v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 245 (1977)

(per curiam) ............................ 20

Darden v. Wainwright, 725 F.2d 1526

(11th Cir. 1974) (en banc) .................. 63,64

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1976) ......*.... 46,64

Davis v. State, 665 P.2d 1186 (Okla. Cr. 1983) * * -• 59,60

DeStefano v. Woods, 392 U.S. 631 (1968)

(per curiam) ............................. ^

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968) ........ 18

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979)........ 26,50

Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982) .... 88

iii

Estelle v. Williams, 425 U.S. 501 (1976) ........ 21

Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532 (1975) ............. 21

Friend v. Leidinger, 588 F.2d 61 (4th Cir. 1978) .. 17

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) .......... 33

Gall v. Commonwealth, 607 S.W.2d 97 (Ky. 1981).... 59

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1977) ......... 55

■. Granviel v. Estelle, 655 F. 2d 673 (5th Cir. 1981) ,

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1003 (1982) ......... 63

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) ........... 33

Grigsby v. Mabry, 637 F.2d 525 (8th Cir. 1980).... 5,28,47

Grigsby v. Mabry, 569 F.Supp. 1293

(E.D. Ark. 1983) .......................... 5,6,24,28,47

Grijalva v. State, 614 S.W.2d 410

(Tex.Cr.App. 1981) ......................... 64

Groppi v. Wisconsin, 400 U.S. 505 (1971) ........ 19

Hance v. Zant, 696 F.2d 940 (11th Cir. 1983) .... 64

Hogge v. Johnson, 526 F.2d 833 (4th Cir. 1975) ... 18

Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1,

616 P.2d 1301 (1980) ....................... 5,28,44,47

Hutchins v. Woodard, No. 84-8050

(4th Cir. March 9, 1984) ................... 48

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961) .............. 19,24,32

Johnson v. Mississippi, 403 U.S. 212 (1971) ..... 18

Jones v. Pitt County Bd. of Ed., 528 F. 2d 414

(4th Cir. 1975) ........................... 17

Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976) ............. 33

Katz v. Dole, 709 F.2d 251 (4th Cir. 1983) ...... 17

Justus v. State, 542 P.2d 598 (Okla.Cr. 1975) ,

vacated on other grounds, 428 U.S. 907 (1976) ... 59,60 '

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978) ........... .33,51,52 55

IV

Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455 (1971)...... 21

McCorquodale v. Balkcom, 721 F.2d 1493

(11th Cir. 1983)(en banc) ................... 63

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971)........ 33

Moore v. Balkcom, 670 F.2d 56 (5th Cir. 1982)...... 64

Moore v. Midgette, 375 F.2d 608 (4th Cir. 1967).... 77

In re Murchison, 340 U.S. 133 (1955)............... 18,21

O'.Bryan v. Estelle, 714 F. 2d 365 (5th Cir. 1983) •••• 63

O'Neal v. Gresham, 519 F.2d 803 (4th Cir. 1975).... 17,18

Parker v. North Carolina, 397 U.S. 790 (1976) ...... 56

People v. Goodridge, 76 Cal.Rptr. 421,

452 P.2d 637 (1969) .........................., 63

People v. Valasquez, 162 Cal.Rptr. 306,

606 P.2d 341 (1980) .........................., 64

People v. Vaughn, 78 Cal.Rptr. 186,

455 P. 2d 122 (1969) ......................... .. 63

People v. Washington, 80 Cal.Rptr. 186,

458 P.2d 479 (1969) ......................... . 63

People v. Word & Sparks, No. 78647 (Super. Ct.

Santa Clara Co. 1981) ....................... . 5

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972) .............. . 26

Pierson v. State, 614 S.W.2d 102

(Tex.Cr.App. 1981) .......................... . 64

Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U,.S. 242 (1976 ).......... . 33

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) .... . 17

Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957) ................ . 55

Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976) ......... . 62

Rosales-Lopez v. United States, 451 U.S. 182 (1981) ___24

Rose v. Lundy, 455 U.S. 509 (1982) ............... . . 25

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966) .......... . . 19,20,21

Smith v. Balkcom, 666 F.2d 573 (5th Cir. 1981) .... . . 28

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1946) ..............

V

Smith v. University of North Carolina,

632 F. 2d 316 (4th Cir. 1980) ..................... 17

Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582

(5th Cir. 1978) ................................ . . 28,33

State v. Adams, 76 Wash.2d 650 , 458 P.2d 558 (1969).... 64

State v. Avery, 299 N.C. 126, 261 S.E.2d 803 (1980) ... 51

State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A.2d 20 (1968) ...... 59,60

State v. Pruitt, 479 S.W.2d 785 (Mo. 1982) .......... 60,63

State v. Ross, 343 So.2d 722 (La. 1978) .............. 59,62

State v. Szabo, 94 111.2d 327, 447 N.E.2d 193 (1983)... 63

State v. Wilson, 57 N.J. 39, 269 A.2d 153 (1970) ...... 59,60

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ....... 26

Taylor v. Hayes, 418 U.S. 488 (1974) ................. i8

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975) .............. 19,26,50

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1945).... 19

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927) ................... 20

United States v. Harper, ____ F.2d ____

(9th Cir. April 3 , 1984) ........................ 47

United States v. Jones, 608 F.2d 1004 (4th Cir, 1979).. 24,32

United States v. Warwick Mobile Home Estates,

537 F. 2d 1148 (4th Cir. 1978) ................... 17

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1978)........ 56

Villareal v. State, 576 S.W.2d 51

(Tex.Cr.App. 1979) ............................. 59,63

Ward v. Monroeville, 409 U.S. 57 (1972).............. 20

Wardius v. Oregon, 412 U.S. 470 (1973)............... 22

White v. State, 674 P.2d 31 (Okla.Cr. 1983 ) .......... 61,63,64

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1975) ............. 26,47

Williams v. Maggio, 679 F.2d 381 (5th Cir. 1982) ,

cert, denied, ____ U.S.____, 77 L.Ed.2d 1399

(1983) 63

Williams v. State, 542 P.2d 544 (Okla.Cr. 1975),

vacated on other grounds, 428 U.S. 907 (1976)

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)

Witt v. Wainwright, 707 F.2d 1196

cert, denied, ___ U.S.____,

(U.S. May 1, 1984) .........

(11th Cir. 1983) ,

52 U.S.L.W. 3786

Other Authorities

Rule 52(a), F.R.Civ.Pro. ......................

S. PENROD & HASTIE, INSIDE THE JURY (1983) .......

Zeisel & Diamond, "The Effect of Peremptory

Challenges on Jury and Verdict: An Experiment

in a Federal District Court," 30 STAN L. REV.

491 (1978) ...................................

Passim

59

63,64

17

36

38

v n

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 84--6139L

SAM GARRISON, et al.,

Respondents-Appellants,

-against-

CHARLES BRUCE KEETEN,

Petitioner-Appellee.

No. 84--614-0

ROBERT HAMILTON, et al.,

Respondents-Appellants,

-against-

BERNARD AVERY,

Petitioner-Appellee.

No . 84--614-1

NATHAN RICE, et al.,

Respondents-Appellants,

against-

LARRY DARNELL WILLIAMS,

Petitioner-Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of North Carolina

Charlotte Division

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS-APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. May the extensive factual findings made by

the District Court, amply supported by substantial record

evidence and not clearly erroneous, be overcome by the

State on appeal?

2. Is there substantial support in the record

for the District Court's finding that death-qualification

produces juries that are uncommonly prone to convict?

3. Is there substantial support in the record

for the District Court's findings that death-qualification

produces juries that are disproportionately favorable to the

prosecution in their attitudes and predispositions?

4.. Is death-qualification unconstitutional be

cause of the proven fact that it produces juries that are

"less than neutral on the issue of guilt," i.e., that it

permits the State to enhance its chances of obtaining a

conviction by asking that the defendant receive a sentence

of death?

5. Is there substantial support in the record

for the District Court's finding that jurors who are ex

cluded by death-qualification are a sizeable and distinctive

group in the community, and that they share a distinctive

constellation of attitudes on important criminal justice

issues?

6 . Is death-qualification unconstitutional be

cause it systematically removes a "cognizable group" of

prospective jurors from the jury pool available to try

capital cases?

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Introduction

The common issues on these appeals concern a

procedure known as "death-qualification" under which

prospective jurors in capital trials in North Carolina are

examined at length during voir dire on their attitudes

toward the death penalty. All jurors who state that they

could never consider a sentence of death are subject to

systematic exclusion for cause by the State, not merely

from the penalty phase, but from the guilt-or-innocence

phase as well — even if it is established on voir dire

that these jurors could serve fairly and impartially in

determining guilt or innocence.

No question is presented on these appeals con

cerning the State's authority to remove from the penalty

phase those jurors who could not consider imposing a penalty

of death, nor is any question raised concerning the State's

authority to remove, at the guilt phase, those whose opposi

tion to the death penalty would prevent them from serving as

fair and impartial jurors on the issue of guilt or innocence.

Neither do petitioners question the State's right to use all

of its peremptory challenges to exclude any prospective

jurors it chooses.

The narrow question presented here is whether the

State is constitutionally entitled to an unlimited number of

challenges for cause to exclude from the guilt or innocence

phase all jurors who could follow the law and serve fairly

to determine guilt or innocence in a capital case, yet who

3

could not impose a sentence of death in a subsequent penalty

proceeding, if any (hereinafter "Witherspoon excludables").

Petitioners contend that the systematic removal of this group

of venirepersons from their juries severely and unconstitution

ally prejudiced their rights to fair and impartial juries on

__1/

the issue of guilt.

Petitioners have established below that this group

of prospective jurors share distinctive attitudes, not merely

toward the death penalty, but toward a range of criminal justice

issues, and that juries deprived of the perspectives of such

"Witherspoon excludables" are more prone to favor the prosecu

tion than are ordinary juries, and more likely than ordinary

juries to convict. The District Court has held that, because

of these effects, death-qualification violates their Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendment rights to a fair and impartial jury, and

to a tribunal selected from a representative cross-section of

the community.

The record in this case consists primarily of the

transcripts and exhibits of three earlier evidentiary hearings

on the effects of death-qualification: (i) the hearing in the

1/ As used throughout this brief, references to the deter

mination of "guilt" are intended to include (in addition to

the overall question of conviction or acquittal) the deter

mination of the kind of homicide that may have been committed

(murder or manslaughter), the degree of the offense and the

sanity of the defendant.

consolidated cases Grigsby v. Mabry (No. PB-C-78-32),

Hulsey v. Sargent (No. PB-C-81-2), and McCree v. Housewright

(No. PB-C-80-429), all heard by the Honorable G. Thomas

Eisele (E.D. Ark., July-August, 1981) and decided in Gngshy

v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1293 (E.D. Ark., 1983)(hereinafter

" 2/"Grig. Tr." )1 (ii) the hearing in People v. Moore, No-..67.113

(Superior Court, Alameda County, California, August-September,

1979), which formed the record for the California Supreme

Court's opinion in Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal. 3d 1, 616

P.2d 1301 (1980)(hereinafter "Hovey Tr.”); and (iii) the record

in People v. Myron Eugene Word and Wendell Herbert Sparks, No.

78617, (Superior Court, Santa Clara County, California, August

1981)(hereinafter "Word Tr."). These records focus on an

extensive series of social scientific studies on the effects

of death-gualification.

Although the State has appealed the District Court's

judgment in this case, it has not at any point offered a co

herent summary of the scientific record on which that judgment

is based. This omission is perhaps understandable, for the

evidence in this case is exceedingly one-sided: it provides

overwhelming support for petitioners' contentions, and it does

not contain a single study on death-gualification that supports

the State's claims. (Indeed, as we will discuss infra, the

2/ In Grigsby v. Mabry, 637 F.2d 525, 528 (8th Cir. 1980),

the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

directed the District Court to hold an evidentiary hearing

on several factual questions determinative of petitioners'

conviction-proneness claim because "if they are answered in

the affirmative, Grigsby has made a case that his constitu

tional rights have been violated and he would be entitled

to a new trial." Id. at 527. Following an evidentiary hearing

5 [Cont'd .]

studies on which the State does attempt to rely underline

the weakness of its position.) Since the facts are essential

to an understanding of the District Court's holding, we will

j W

briefly set them forth here.

One of the petitioners in this appeal, Larry Williams,

also prevailed below on an individual claim, that at least one

juror was excluded for cause from his capital jury in violation

of Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). That issue

will be addressed following our discussion of the common

claims.

(ii) Legal Background

In 1968, the Supreme Court decided Witherspoon v .

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968). The petitioner in Witherspoon

had challenged, on two separate grounds, the prosecutor's statu

tory right in Illinois to "death-gualify" a capital jury, that

is, to exclude all prospective jurors, for cause, solely because

of their "'conscientious scruples against capital punishment,

Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, 391 U.S. at 512. First, he

urged that no jurors be excused at the guilt phase, irrespective

of their attitudes towards the death penalty, so long as they

could be fair and impartial in determining guilt or innocence.

Juries selected by excluding such jurors, he contended, " . . .

_2/ cont'd.

at which various experts, seventeen social scientific studies

and 270 exhibits were presented, the District Court found that

the "death-qualification" process used in Arkansas created juries

that were conviction-prone and denied the petitioners trial by a

jury representative of a cross-section of the community. G*"^qsby

v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1293 (E.D. Ark. 1983), pending en banc,

No. 83-2113EA (8th Cir.).

3/ In addition, we have provided the Court with a set of summarie

of the most important studies that are included in the record, with

relevant recor'd references, as an Appendix to this brief.

_ p, -

f conviction [and]"must necessarily be biased in favor o

partial to the prosecution on the issue of guilt or innocence."'

Id. at 516-17. Secondly, he argued that jurors should not be

excluded at the penalty phase "simply because they voiced

general objections to the death penalty," id. at 522, unless

those reservations left the jurors unable fairly to consider

the full range of penalties, that is, unless they would auto

matically oppose a death sentence, regardless of the facts and

circumstances of the case before them.

The Supreme Court agreed with the petitioner's second

argument, and forbade exclusion of prospective jurors "on any

broader basis" than an opposition to the penalty so strong that

the jurors would either (i) automatically vote against death in

any case or (ii) be rendered incapable of making "an impartial

decision as to the defendant's guilt given the prospect of a

death sentence." Id. at 522-23, n.21 (emphasis in original).

The Court, however, refused to accept petitioner s

claim that the guilt-phase excusal of jurors who could never

impose death, but who could be fair at the guilt phase, rendered

the resulting jury conviction-prone. Observing that ”[t]he data

adduced by the petitioner . . . are too tentative and fragmentary

to establish that jurors not opposed to the death penalty tend to

favor the prosecution," id. at 517, the Court declined "either

on the basis of the record now before us or as a matter of

judicial notice," id at 518, to accept this claim. However, the

Court explicitly invited further evidence on the issue. Id.

at 520 n.lSI See also Bumper v. North Carolina, 391 U.S. 543,

52.5 ( 1968 ) .

7

(iii) Procedural History Of These Cases

The procedural history of these cases is adequately

set out in the brief for appellants-respondents filed on this

_£/

appeal. (See Atty. Gen. Br. 2-3).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

It is impossible to review adequately the scientific

evidence offered by petitioners within the limits of this brief;

we will confine our discussion to the major points. The studies

and the expert testimony address three separate factual issues:

(i) the differences in the attitudes of death-qualified and

Witherspoon excludable jurors; (ii) the differences m the behavior

of these two groups of jurors; and (iii) the effect on prospective

jurors of the process of death-qualifying voir dire itself.

(i) Death-Qualification And Juror Attitudes

The evidence presented on the relationship between

death penalty attitudes and attitudes on other criminal justice

issues does not permit conflicting interpretations: people

who oppose the death penalty strongly, and those who are excluded

from capital cases under Witherspoon in particular, have attitudes

that are more favorable to the accused on a range of issues

material to the criminal justice process. Half a dozen separate

5/studies support this proposition (see Pet. App., pp. 1-6.) ana

none contradict it; the State's experts apparently conceded.

this point. See, e ^ . , Grig. Tr. 1081-82(Dr. Gerald Shure);

2/ Each reference to the Brief of Appellants,, dated April 10,

T982, will be indicated by the abbreviation "Atty. Gen. Br.,"

followed by the number of the page on which the reference may

be found.

5/ Each reference to Petitioners' Appendix, which follows the

text of this brief, will be indicated by the abbreviation "Pet.

App." followed by the number of the page on which the reference

may be found. _ q _

Grig. Tr. 1221-22 (Dr. Roger Webb). The District Court

found that

"[t]he evidence before the court overwhelmingly

demonstrates that persons who are unwilling to

impose the death penalty share a unique set of

attitudes toward the criminal justice system which

separate them as a group not only from persons who

favor the death penalty, but also from persons who

are generally opposed to the death penalty, but are

willing to consider it in some cases."

6/(J.A. 122-25). This constellation of attitudes shared by

Witherspoon excludables includes, for example, more open

attitudes toward the insanity defense (J.A. 98, 101), greater

willingness to honor constitutional restrictions on the

admissibility of evidence (J.A. 99, 101), less partiality

toward prosecutors (J.A. 103), and greater reluctance to assume

that defendants would not be brought to trial unless they were

guilty (J.A. 99).

After "thoroughly review[ing] the evidence submitted

by petitioners," (J.A. 112), and finding it "credible, consistent,*

and essentially uncontradicted," id., the District Court expressly

held that persons who are unwilling to impose the death penalty

are a "distinctive group" in the community:

"The results of the studies submitted

by petitioners reveal that persons who

are unwilling to impose the death penalty

share a unique set of attitudes toward

the criminal justice system which separates

them as a group not only from persons who

favor the death penalty, but also from per

sons who are generally opposed to the death

penalty, but are willing to consider it in

some cases. These attitudes are consistently

more favorable for the defense than they are

for the prosecution."

(J.A. 125).

5/ Each reference to the Joint Appendix will be indicated

by the abbreviation "J.A." followed by the number of the page

on which the reference may be found.

9

Petitioners' experts also testified about a second

important feature of death penalty attitudes: because a

greater proportion of blacks than of whites, and of women

than of men, are inalterably opposed to the death penalty,

blacks and women are subject to removal through the process

of death-qualification in greater proportions than are whites

and men. The District Court found that

"[exclusion of persons unwilling to impose

the death penalty from the guilt phase of

capital trials further offends the Sixth

Amendment in that it inevitably leads to

the disproportionate exclusion of distinctive

groups such as blacks and women, who tend to

oppose the death penalty to a greater degree

than white men.

(j.A . 126). In so finding, the Court relied upon a long series

of surveys, including a 1971 Harris national survey that showed

that "[f]orty-six percent of black subjects stated that they

could never vote for the death penalty, while only 29% of white

subjects said they could never impose it . . .[and o]nly 24%

of men subjects [but] . . . 37% of women said they could never

vote for it." (J.A. 105). (See also Pet. App., 6a-7a).

The uncontradicted evidence thus confirms that

Witherspoon excludable jurors share unique attitudes toward

the criminal justice system, and that their systematic exclusion

for cause saddles defendants with those prospective jurors most

predisposed to favor the prosecution and to convict. It also

disproportionately excludes blacks and women from capital

j uries.

(ii) Death-Qualification And Juror Behavior

Petitioners offered additional evidence addressed,

not to whether death penalty attitudes are related to other

10

criminal justice attitudes, but to whether death penalty

attitudes systematically affect the behavior of jurors.

"[Piersons who are willing to impose the death penalty not

only share a set of attitudes that are more favorable to the

prosecution, but are also predictably more likely to decide

in a manner that favors the prosecution." (J.A. 133).

The District Court reviewed a series of nine studies,

conducted by independent researchers over a twenty-five-year

period, in which participants ranging in age and status from

college students to actual jurors made guilt or innocence

determinations in a variety of contexts. Some read short

written descriptions of crimes before casting their ballots.

Others heard audio accounts of criminal proceedings; in still

other studies, videotaped reenactments of criminal trials were

employed. One study obtained the jury verdict preferences of

jurors who had participated in actual trials. The Court found

that:

"[sjeveral studies submitted by petitioners

specifically concentrated on the manner in which

pro-prosecution attitudes on the part of death

qualified jurors translate into pro-prosecution

behavior. The results of these studies were con

sistently the same: with due consideration of

the strength of the evidence, persons who are

willing to impose the death penalty will vote

to convict more often than will persons who

are unwilling to impose the death penalty.

(J.A. 133).

The studies, in short, uniformly demonstrate that

persons who are death-qualified by Witherspoon standards are

substantially more likely to vote to acquit than are persons

excluded by those standards. In the most sophisticated and

carefully controlled study, the Ellsworth Conviction Pronenes;

Study 1979, 288 adult, jury-eligible citizens were asked to

11

view a videotaped reenactment of an actual murder trial.

The results showed that "[i]n this close case, 77.9,4 of

the death-qualified jurors [willing to impose the death

penalty] convicted the defendant of some degree of homicide,

while only 53.3% of the currently excludable jurors voted

that way." (J.A. 134; see id. 107). Moreover, the study

found significant differences between death-qualified and

excludable jurors, not only in the overall percentage of guilty

verdicts, but in the degree of guilt imposed (from manslaughter

to first degree murder) among the possible verdict outcomes.

7/

(J.A. 500; see also Pet. App. 5a-6a.

7/ Dr. Ellsworth's follow-up studies included a simulation

of jury deliberations among 228 of the subjects who had witnessed

the videotaped trial. The jurors were grouped into panels of

12 persons; half of these jury panels had only death-qualified

subjects, and half included two, three or four Witherspoon

excludable subjects ("mixed juries"). The subjects were

asked to fill out a questionnaire about the trial. The

questionnaire data revealed that subjects on mixed juries

remembered the facts of the case better than those on death-

qualified juries, and that they viewed all witnesses, prosecu

tion and defense, more critically than did subjects on death-

qualified juries (J.A. 560-63; see Pet. App. 5a-6a.

The District Court found that "[this] process of excluding

jurors with differing backgrounds and viewpoints results in

reduced jury deliberation . . ., a situation explicitly con

demned by the Supreme Court in Ballew v. Georgia, supra, and

by the State in this case." 136) .

12

(j_j_i) The Process of Death-Qualification

Petitioners' experts further testified, based upon the

research of Professor Haney, that the process of death-qualifica

tion — the searching voir dire inquiries from the court and

from counsel on prospective jurors' attitudes toward the

death penalty — itself biases jurors on the question of

guilt or innocence. "The presumption of prejudice [against the

defendant]," the District Court found, "is only escalated by

a series of undesirable side effects which result from death

qualification of jurors selected for the guilt phase of a

■trial. The voir dire itself tends to instill in the jury

a sense that the defendant is guilty, and that the death penalty

is the appropriate penalty for him." (J.A. 136; see J.A. 615-22).

13

ARGUMENT: PART ONE THE COMMON ISSUES

I

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY HELD THAT THE

STATE'S USE OF DEATH-QUALIFICATION PROCEDURES

TO EXCLUDE IMPARTIAL JURORS AT THE GUILT-OR-

INNOCENCE PHASE OF PETITIONERS' CAPITAL TRIALS

DENIED THEIR SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

RIGHTS TO FAIR AND IMPARTIAL JURIES___________

A . The District Court's Findings on Conviction-Proneness

Perhaps the most striking quality of the proceedings

in the District Court is the care with which that Court examined

the factual issues in this case, on the basis of an exhaustive

record. Virtually all relevant social scientific evidence

developed within the past thirty years — from Professor Zeisel's

1954-55 field research involving actual jurors, to Professor

Ellsworth's highly sophisticated series of studies in 1979

was placed before the Court and was subjected to intense pro

fessional scrutiny and review. Equally striking are the results

of the studies: no matter who conducted the research, no matter

what locale or subjects, no matter what the methods used, death-

qualified jurors were shown significantly more prone to convict,

more favorable to the prosecution in their attitudes, and more

prone to believe the prosecutor and his witnesses, than were

Witherspoon-excludable jurors.

In the Hovey Record, Professor Hans Zeisel illustrated

his testimony on the cumulative impact of the conviction-prone-

ness studies with a chart (see copy of Hovey Exh. HZ-5, infra)

summarizing the strong points and the weak points of each of

the six major studies on conviction-proneness (see also, Pet.

App. 8a-13a). He explained:

"The reason I have put these six studies

together is the following, namely, I'm sure

that it couldn't escape anybody who has

SY

NO

PS

IS

U,

»

,

tw

n

Sl

BO

Mf

i

P

u

iM

H

-O

f-

IM

^

^

tl

tA

L^

lt

lJ

0M

S

lU

D

U

i

Defendant’s jExhibit No. HZ’" $

FIGURE He. 3 7

listened to this testimony . . . the almost

monotony of the results. It is obviously

the same whether you take the experiment at

Sperry-Rand in New York or students in Atlanta

or jurors in Chicago or Brooklyn or eligible

jurors here in Stanford; it comes always out

the same way.

"And Your Honor, I should add that it happens

seldom in the social sciences that the problem

is being studied even twice, not to speak of

six times. . . .

"So this is an unusual fact. And since all of

the studies show the same result, no matter with

whom, no matter with what stimulus, no matter

with what closeness of simulation, there is

really one conclusion that we can come to.

The relationship is so robust -- and this is

a term of art among scientists -- that no matter

how strongly or how weakly you try to discover

it in terms of your experimental design, it

will come through."

(Hovey Tr. 84-085). Professor Zeisel' s conclusion is greatly

reinforced by the consistent findings of an extensive series

of surveys that compared the attitudes of death-qualified and

excludable jurors (see Pet. App. la-7a ), and by several

experimental studies that examine the mechanisms that produce

these effects and the impact of the process of the death-qualify

ing voir dire itself (see Pet. App. 12a-15a).

By contrast the record is utterly bare of any studies

that contradict this well established finding. This absence

cannot possibly be attributed to any lack of opportunity on

the State's part to prepare and present evidence. As the pro

cedural history of this case demonstrates, the State had,

literally, years within which to put any relevant matters

before the court. Rather, the state of the record reflects

the fact that in the sixteen years since the Supreme Court

identified the issue in Witherspoon, despite intense academic

and legal interest in the issue, not a single contrary,

15

scientifically credible study has been reported, and the

State offered no suggestion that such a contrary study

might be in progress. From a scientific point of view this

record is clear; the facts on conviction-proneness are known.

Based on this record, the District Court reached the only

conclusion possible:

"[This] evidence demonstrates that what

common sense says is so, is so: jurors

who favor the death penalty are significantly

more likely to convict and jurors who oppose

the death penalty are significantly less likely

to convict.

There is no serious evidence refuting those

propositions.

A fair jury has not been provided when the

prosecutor is able to keep on the jury those

persons most likely to convict and to exclude

from the jury for cause all those persons most

likely to acquit."

(J . A. 89).

3 . The Applicable Standard Of Review Of Those findings

It is no surprise that the State studiously avoids

the factual record and the District Court's findings, since the

evidence so thoroughly refutes its contentions. The State's

understandable desire to ignore those findings, however, runs

squarely afoul of Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, which provides that such findings shall not be

set aside unless clearly erroneous,and due regard shall be

given to the opportunity of the trial court to judge the

credibility of witnesses." The Supreme Court of the United

States has recently amplified the principles governing the

appellate review of factual findings, holding that 52(a) applies

to the trial court's treatment of all "ultimate" issues that turn

16

on factual findings, as well as its disposition of "subsidiary"

f acts:

Rule 52(a) broadly requires that findings of

fact not be set aside unless clearly erroneous.

It does not make exceptions or purport to exclude

certain categories of factual findings from the

obligation of a court of appeals to accept a

district court's findings unless clearly

erroneous.

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 287 (1982).

This Court has long adhered to the view that "[i]t

is not the function of the appellate court to decide factual

questions de novo; the function of this court under Rule 52(a)

is not to determine whether it would have made the findings

the trial court made, but whether 'on the entire evidence it

is left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake

has been made.'" United States v. Warwick Mobile Home Estates,

537 F. 2d 1148, 1150 (4th Cir. 1976)(citations omitted).

Specifically, this court has emphasized that "[w]e may not

weigh the evidence, pass on the credibility of witnesses, or

substitute our judgement for that of the finder of facts.

Canron Inc, v. Plasser American Corp., 609 F.2d 1075 (4th

Cir. 1979); accord: Bonds v. Mortensen 8 Lange, 717 F.2d 123

(4th Cir. 1983), Katz v. Dole, 709 F.2d 251 (4th Cir. 1983),

Smith v. University of North Carolina, 632 F.2d 316 (4th Cir.

1980), Friend v. Leidinger, 588 F.2d 61 (4th Cir. 1978), Jones

v. Pitt County Bd. of Ed., 528 F.2d 414 (4th Cir. 1975).

The rule has been applied by this Court with equal

force to district court findings based upon conflicting docu

mentary evidence. Moore v . Midgette, 375 F.2d 608, 612

(4th Cir. 1967); see also Friend v. Leidinger, supra; 0'Neal

17

v. Gresham, 519 F . 2d 803 (2-th Cir. 1975); Hogge v. Johnson,

526 F.2d 833 (2th Cir. 1975); B's Company, Inc, v. B.P.

Barker 8 Associates, 391 F .2d 130 (2th Cir. 1968). Where,

as on these appeals, the District Court "has thoroughly

reviewed the evidence . . . , finds it credible, consistent,

and essentially uncontradicted, . . . and accepts the opinions

offered by experts in jury research that the studies are valid

and reliable," Keeten v. Garrison, supra, 578 F. Supp. at 1177,

its findings should not be lightly disturbed.

C. The Controlling Legal Principles

The Sixth Amendment guarantees that "[i]n all criminal

prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a . . . trial,

by an impartial jury . . . ." Even before Duncan v. Louisiana,

391 U.S. 125 (1968), incorporated the Sixth Amendment's jury-

trial right into the Fourteenth, it had long been settled that

the Due Process Clause assures every criminal defendant the right

to have his trial before an impartial tribunal. "A fair trial

in a fair tribunal is a basic requirement of due process." In

re Murchison, 329 U.S. 133, 136 (1955). See, e . g. , Tay,lQ£—Xj_

Hayes, 218 U.S. 288, 501 (1972)(citing authorities). Johnson

v. Mississippi, 203 U.S. 212, 216 (1971)(per curiam).

Witherspoon itself was technically not a Sixth

-----3 7

Amendment case, but the ground of its decision demonstrates

8/ Although it was decided two weeks after Duncan v. Louisiana,

■Jgi u.S. 125 (1968), in which the Court held the Sixth Amendment

jury trial right applicable to the states, Witherspoon v. Illinois

did not rely on Duncan, and it ultimately relies on the Four-

teenth Amendment in holding that the execution of Witherspoon s^

death sentence would "deprive him of life without due process of

law." 391 u.S. at 523. The Court subsequently held that Duncan's

incorporation of the Sixth Amendment into the Fourteenth did not

[Cont'd .]18

how fundamental jury impartiality is to the guarantee of due

process in jury trials. The Court there found that the pro

cedure by which Witherspoon's jury had been selected denied

him "that impartiality to which [he] . . • was entitled under

the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments," 391 U.S. at 518, in the

determination of his sentence. A fortiorari, where a State

entrusts the determination of guilt or innocence to a jury,

"[d]ue process requires that the accused receive a trial by

an impartial jury free from outside influence." Sheppard v .

Maxwell, 384- U.S. 333, 362 (1966). "In essence, the right to

jury trial guarantees to the criminally accused a fair trial

by a panel of impartial, 'indifferent' jurors . . . In the

language of Lord Coke, a juror must be . . . indifferent as

he stands unsworne.'" Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717, 722 (1961),

accord, Groppi v. Wisconsin, 400 U.S. 505, 509 (1971).

The Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment right to "an

impartial jury" means something more than that each juror be

individually capable of fairly and impartially assessing the

facts in light of the law on which he is instructed. The jury

as a whole should be composed in such a way that its collective

assessment of the facts will reflect the "conscience of the

community." Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, 391 U.S. at 519.

This requirement of collective, or "diffused impartiality,"

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975); Thiel v. Southern

Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217, 227 (1945)(Frankfurter, J. dissenting),

8/ Cont'd.

apply retroactively to state-court trials that, like Witherspoon's,

had predated the Duncan decision. DeStefano v. Woods, 392 U.S.

631 (1968)(per curiam).

19

was described in Witherspoon as the requirement of jury

"neutrality;" accord Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 44 (1980).

The record in this case demonstrates two ways in

which death-qualification deprives a capital defendant of his

right to a neutral jury. First, it demonstrates that a death-

qualified jury is partial in its predisposition. It is a jury

that is more inclined than others, at the very outset of the

trial, to side with the prosecution. Second, the record proves

that a death-qualified jury is partial in its performance.

Faced with the identical case, a death-qualified jury is more

likely to vote to convict than a jury that is truly represen

tative of the entire community.

The courts have long held that any procedure that

might predispose a criminal tribunal to favor the State violates

due process. In Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927), the Court

held that

'[e]very procedure which would offer a

possible temptation to the average man

as a judge to forget the burden of proof

required to convict the defendant, or which

might lead him not to hold the balance nice,

clear and true between the state and the accused

denies the latter due process of law.

Id. at 532. See also, Ward v. Monroeville, 409 U.S. 57 (1972);

normally v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 245, 245 (1977)(per curiam).

Applying this constitutional rule to the record in

the present case involves a task analogous to evaluating the

consequences of pretrial publicity. In both situations, it is

necessary to assess the danger that events preceding the pre

sentation of the evidence might change the jury’s disposition

when it comes to judge that evidence. In Sheppard v. MaxweJUL,

20

384 U.S. 333 (1966), the Supreme Court held that

[t]he trial courts must take strong measures

to ensure that the balance is never weighed

against the accused. And appellate tribunals

have the duty to make an independent evaluation

of the circumstances.

Id. at 362. That basic canon of due process is recognized in a

variety of situations which endanger the impartiality of the

trier of criminal charges. Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532, 543-

4.4. (197 5) ; Mayberry v. Pennsylvania, 400 U.S. 455 (1971),

Estelle v. Williams, 425 U.S. 501, 504 (1976); In re Murchison,

349 U.S. 133, 136 (1955). Death-qualification, however, con

trary to the Court's admonition in Sheppard v. Maxwell,

dramatically skews the predispositional balance of the jury

pool in a way that creates a jury pool that is "weighted./against

the accused."

Witherspoon also identifies the second type of non

neutral jury forbidden by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments,

a jury that is in actual practice, uncommonly prone to convict.

391 U.S. at 517. A death-qualified jury, the evidence in this

case demonstrates, is just such a tribunal. This biasing effect

in the performance of death-qualified capital juries is demon

strated on this record not only as an inference from the death-

qualified jury's proven pretrial predisposition, but also as

an observed fact of its trial performance. The factual question

that the Court in Witherspoon found unanswered — whether death-

qualification "substantially increases the risk of conviction,"

391 U.S. at 518 — has now been answered in the affirmative.

Six major studies demonstrating the conviction-prone-

ness of death qualified juries, together with a number of

supporting explanatory studies were before the District Court.

21

They were explicated and dissected on direct and cross examine

tion by prominent expert witnesses for petitioners and by the

State's witnesses. The District Court has found them credible

and persuasive. No contrary studies exist.

"[T]he Due Process Clause . . . speak[s] to the

balance of forces between the accused and his accuser.

Wardius v. Oregon, 4-12 U.S. 470, 474 (197o) . As petitioners

conviction-proneness studies all conclude, death-qualification

destroys that balance. It is therefore unconstitutional.

D. The State's Arguments for Reversal

The State, in discussing the evidence, exhibits a

curious ambivalence toward the scientific research that is

before this Court. On one hand, it argues that sixteen

years and some twenty carefully researched studies after

Witherspoon, "the showings required by Witherspoon have still

not been made and that the research is still fragmentary,

(Atty. Gen. Br., at 12); at the same time, it claims that

"when closely analyzed for impact, it [the research] favors

respondents." (Id.)

In the body of its argument, the State expands its

position into a list of arguments that appear to be contra

dictory as well as untenable: (i) that petitioners have no

standing to raise this issue; (ii) that the research does not

demonstrate that death-qualified jurors are, individually,

legally disqualified to serve because of bias; (iii) that

jurors who would never consider the death penalty, but who

state under oath that they could fairly and impartially deter

mine a capital defendant's guilt or innocence, must not be

trusted to do so; (iv) that the entire body of petitioners'

22

research is scientifically unsound and unreliable, as demonstrated

by studies by Dr. Steven Penrod and Professor Hans Zeisel; and

(v) that, in any event, the demonstrated bias of death-qualified

juries is constitutionally insignificant because it might

change the outcome in [only] from 1-10% of close [capital]

cases." (Atty. Gen. Br., at 13). We will address these argu

ments in turn.

(i) Petitioners' Standing

The State's first argument is that the District Court

must be reversed because petitioners "failed to show that the

jurors excluded [by death-qualification] could have been fair

and impartial on the guilt phase . . . ." (Atty. Gen. Br., at

14.). The State makes this argument despite the fact —

acknowledged in its own brief — that at least some of these

excluded jurors in each case testified under oath that they

could return a verdict on guilt in accordance with the instruc

tions of the court." (Atty. Gen. Br., 4-7). The State, it seems,

considers such a sworn statement by a venireperson insufficient

to overcome a challenge that was never, in fact, actually raised.

One hardly knows where to begin to respond to this

argument. The shortest answer is that the State has placed the

shoe squarely on the wrong foot. The State did not challenge

these jurors at trial on the ground that they could not be fair

on guilt. Therefore it is now precluded from claiming that

it might have been able to challenge the jurors on that ground.

These jurors were excluded, by the State, on another ground,

that they would never consider imposing the death penalty. It

is those actual exclusions that are on review, not some hypo

thetical challenges that were not made. Conceivably, a more

23

detailed inquiry into the jurors' impartiality on guilt would

have revealed that these jurors could not have fairly decided

guilt or innocence (that appears to be the State s position),

more likely, no further questioning was undertaken at the

trials because the jurors' sworn statements of impartiality

were obviously credible to all participants. In any event,

appellate review can only be meaningfully undertaken on the

basis of evidence actually presented and objections actually

made on the trial-court record, not on the basis of post hoc

speculations.

In these particular cases, however, the force of

that basic rule of appellate review is amplified by the sub

stantive law. First, potential jurors are, in general, pre

sumed to be impartial unless the contrary is demonstrated.

"The burden of proving partiality is upon the challenger."

United States v. Jones, 608 F.2d 1004, 1007 (4-th Cir. 1979),

citing Irvin v . Dowd, 366 U.S. 717, 723 (1961); see also Rosales —

Lopez v. United States, 451 U.S. 182, 190 (1981), Grigsby v.

Mabry, 469 F. Supp. 1273, 1283-84 (E.D. Ark. 1983). Witherspoon

adheres to that basic principle in forbidding the State to

exclude venirepersons for cause unless they make it unmistak

ably clear" that they are disqualified. 391 U.S. at 522 n.2l.

The burden, in other words, is on the State to establish that

prospective jurors are not qualified, not on the defendant, to

establish that the jurors are qualified. The State would

turn these rules upside down; it would create a presumption that

venirepersons are biased, and require them to make it unmistakably

24

JL/

clear that they are qualified to serve. That is simply not the

law; "standing" is therefore not a problem on these appeals.

(ii) The Impartiality of Death-Qualified Jurors

The State's second argument is that petitioners have

not shown that death-qualified jurors are biased in a manner

that would disqualify them individually from jury service.

(Atty. Gen. Br., 14— 15). Petitioners, however, are not asking

that death-qualified jurors should be excluded from capital

juries — they are certainly entitled to serve — but rather

that fair and impartial jurors who are now excluded because

of opposition to the death penalty be included in the deter

mination of guilt or innocence. The State's argument reflects

9/ In a related procedural vein, the State claims that peti

tioners' partial reliance on a study demonstrating that the

process of the death -qualifying voir dire biases jurors against

capital defendants (see Haney Study, J.A. 587-522; see Pet. App.

]_2a— 15a) amounts to a separate claim that is unexhausted under

Rose v. Lundy, 4.55 U.S. 509 (1982) with respect to petitioners

Keeten and Avery, although exhausted with respect to petitioner

Williams (Atty. Gen. Br., kk-45). This argument deserves very

little comment. As the District Court ruled, "this study is

but one more piece of evidence offered by petitioners to

support their original claim that the process by which the

juries that tried their cases were selected deprived them of

their right to trial by an impartial facjt — finder. (J.A. 110).

The State attempts to sidestep this obvious fact by arguing that

a different form of relief is required to meet this factual

argument. (Atty. Gen. Br. , at 4-5) . Not so. To reiterate,

petitioners claim that the process of death-qualification

violated their constitutional rights to due process and to

fair and impartial juries. They request, as relief, that

the State be precluded from questioning prospective jurors

about their ability to impose the death penalty until after a

determination of guilt of a capital offense, if any. Such

relief would eliminate or minimize all of the deleterious

effects of the challenged practice.

25

a thorough misunderstanding of the petitioners' claims and

of the opinion below. The State has missed the critical

distinction between impartial jurors and impartial juries.

A juror is fair and impartial if he or she can

fairly try the issue before the court, and reach a decision

based on the evidence and the law. But different fair and

impartial jurors may reach opposing decisions; in fact, that

is a common occurrence. The genius of the system of trial by

jury is that it does not leave the determination of lawsuits

to any one person, whether juror or judge, but relies on the

wisdom of a group chosen from the community, the jury- That

group must consist of fair and impartial individuals, but that

is not enough; it is the essence of the jury that it represent

the community in which the trial takes place. Strauder v .

West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308 (1880); Smith v. Texas_,_

311 U.S. 128, 130 (194-0). Indeed, representativeness is at

the heart of the concept of a fair and impartial jury under

both the Sixth Amendment and the Due Process and Equal Protec

tion principles of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Duren v._

Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979); Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S.

522, 530 (1975); Peters v . Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972),

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1975); Ballard v. Unite_d

States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946).

To choose a common example, it is quite possible

that white and black jurors evaluate certain types of evidence

quite differently; white jurors might be more skeptical, for

instance, of a defendant's claim that a police officer struck

him without justification. This is a legitimate difference

26

both the white and the black venirepersonsin point of view:

may be fair and impartial as jurors, individually. Nonetheless,

the disposition of the jury on this issue could determine the

outcome of the case. To say in such a case that an all-white

jury was prosecution-prone does not imply a criticism of the

point of view of the whites, or embody a judgment that the

defendant's contention is factually correct. The rule is

simply that both of these legitimate points of view must be

icyincluded. That is the relief requested by petitioners, and

that is the issue addressed by the District Court.

icy The State's misunderstanding of the meaning of neutrality

"is exemplified by its discussion of one of petitioners' studies.

In the Ellsworth Post-Deliberation Follow-Up Data, 1979 (the

"Regret Scale" Study)(J .A. 577-80; see also id.,1121-25 for

Dr. Ellsworth's testimony concerning the Regret Study), Dr.

Ellsworth and her colleagues found that death-qualified and

excludable jurors differed in their relative levels of regret

for different types of judicial errors: Witherspoon-excludable

jurors expressed more regret at the prospect of convicting an

innocent person than at the prospect of acquitting a guilty one,

while death-qualified jurors expressed equal levels of regret

for these two types of errors. The State seizes upon the word

"equal" in these findings and argues that their equal levels of

regret demonstrate that death-qualified jurors "are equally fair

to both parties while the excluded jurors would not be." (Atty.

Gen. Br., 33-34).

This is a semantic equation with no content. "Equality is

a virtue only where it is the preferred attitude; there is nothing

praiseworthy, for example, in being equally well disposed toward

good and toward evil. In this case, of course, there is no

clear reason to suppose that one point of view is superior to

the other. The presumption of innocence and the burden of proof

beyond a reasonable doubt strongly suggest that our legal system

embodies the belief that erroneous convictions should be regretted

more than erroneous acquittals, but the belief that these two

tupes of problems are equally serious is also a valid point of

view. It is the State's contention, however, that only the more

punitive view is entitled to expression on capital juries, peti

tioners want both perspectives included.

27

Petitioners have put forward evidence of differences

in predisposition betweeen death-qualified and Witherspoon-

excludable jurors not in order to exclude death-qualified

jurors individually, but because their pronounced predisposi

tion to favor the State is relevant to petitioners' claim

that juries comprised solely of such jurors are not impartial,

in that they are more conviction-prone than fully representa-

11/tive juries.

11/ Although the State has not relied on them, two cases

from the Fifth Circuit — Spinkellink v. Wainwrigh^, 578 F.2d

582 593-94 (5th Cir. 1978) and Smith v. Balkcom, 560 F.2d

573 583-84 (5th Cir. 1981) — set forth a related argument:

that the fact that death-qualified juries are uncommonly con

viction-prone does not mean that they are not impartial, on

the contrary, that non-death-qualified juries are acquittal

prone." With all due respect to the Fifth Circuit, the argu

Sent does not make sense. If ordinary, non-death-qualifled

juries are acquittal-prone and unfair, why are they used m all

criminal triafs except capital cases? The issue here whether

the State can increase a defendant's chances of conviction

tip the balance on guilt or innocence -- by placing him on

trial for a capital crime, rather than a non-capital one. The

Fifth Circuit apparently takes the position that such a balance

can be struck only when the defendant's life is placed in

jeopardy. The Fifth Circuit's position has been rejected

directly by the Eighth Circuit, Grigsby v. Mabry, 637 F.2d

525 527 (8th Cir. 1980), on remand 569 F. Supp. 1273 (E.D.

Ark! 1983), appeal pending, (8th Cir.) and by the California

Supreme Court, Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 19 n.Ai,

516 P. 2d 1301, 1309 n.41, and it is directly contrary to

Witherspoon.

The Court in Witherspoon condemned the systematic

exclusion of opponents of the death penalty from sentencing^

juries because it "stacked the deck against the petitioner

on the issue of penalty. 391 U.S. at 523. If an inordinate

tendency to prefer a particular outcome were constitutionally

acceptable, the Supreme Court would not have condemned this

practice. Yet, the Court recognized that a jury must express

the "conscience of the community," id. at 519, and that its

performance must be measured against the yardstick of -hat

community. Pre-Witherspoon juries failed that test because

they were "uncommonly willing to condemn a man to die." Id.

at 521.

The Fifth Circuit position amounts to a rule that a lesser

standard applies to determinations of guilt in capital cases

[Cont'd.]28

(iii) The Possibility of Partiality on Guilt

— The "Nullification" Argument

state is explicit in acknowledging the inconsistency

of its arguments:

While respondents' position has been that the

attitudes dealt with in the surveys and relied

on by petitioners are not concrete enough . . .

to gauge actual juror behavior . . . [the State's]

position is also that the attitude of strong

opposition to the death penalty will largely

equate with a refusal to convict if the death

penalty can be imposed . . . .

(Atty. Gen. Br., 19-20). Although it confesses that "[ljittle

research has been done on" possible jury nullification by

Witherspoon excludables, (id., at 20), the State nevertheless

proceeds to claim that the research in the record "tends to

support" this claim. (_Id. )

The research in the record does show, of course, that

some potential jurors agree that they would be unable to act

fairly and impartially at the guilt phase of a capital trial

because of their opposition to the death penalty, while others

who are now excluded for opposition to the death penalty could

be fair and impartial on guilt. The actual figures vary, but

the most recent and best studies indicate that a strong majority

IV Cont'd.

than to determinations of penalty, that a jury that is

"uncommonly willing" to convict on capital charges is constitu

tional, despite the implicit contrary holding in Witherspoon.

There is no justification for this distinction; it is directly

refuted both by Beck v. Alabama, 4-4-7 U.S. 625, 638 (1980)

(need for extraordinary reliability attaches to the determination

of guilt as well as the determination of penalty in capital cases),

and by Witherspoon itself.

29

of Witherspoon-excludable jurors could be fair and impartial

on guilt. See, e . g . , Ellsworth/Fitzgerald, 1979,(J.A. 736)

(9% could not be fair). But petitioners have never claimed that

jurors who cannot be fair and impartial on guilt should be per

mitted to sit on capital juries, and the studies particu

larly the most recent ones — have been careful to identify

and exclude such potential jurors. The effects of death-

qualification on the.behavior of juries has been demonstrated,

repeatedly, after taking into account the inevitable and un

contested exclusion of nullifiers. (See, e . Ellsworth,

Thompson and Cowan, 1979, J.A. 539-40; Ellsworth/Fitzgerald ^

1979, J.A. 733; Haney, 1979, J.A. 591; Kadane, 1981, J.A. 799).

the article to

is clear from

the Joint Appendix

. . . now awaiting

12/ The State quotes Professor Hans Zeisel as expressing concern

Ibout a problem of jury nullification if death-qualification is

discontinued. (Atty. Gen. Br., at 23). Here, ^ in o e

places in its brief, the State has quoted from Professor Zeisel

statements selectively and misleadingly. (See also infra, at

The quoted comments are taken from an article published y

Professor Zeisel in 1968 before the Witherspoon decision (a

fact that is not apparent from the excerpt of

which the State cites, at J.A. 347, but which

the entire article which appears in Vol̂ . 3 of

(see J.A. 404: " . . . Witherspoon v. Illinois

hearing in the United States Supreme Court. )

At the time Professor Zeisel wrote these comments, jurors

could be excluded merely for possessing "conscientious scruples

against the death penalty." Witherspoon, of course, resolved

the problem that Professor Zeisel had identified by clearly

articulating two separate and narrow bases for exclusion of

venirepersons for opposition to the death penalty:

to consider the death penalty in any case, and lack of impartial y

on guilt. 391 U.S. at 522, n.2l. If there were no other evidence

in the record, one might wonder whether this legal change has

affected Professor Zeisel's view of this issue, but speculation

is unnecessary: Professor Zeisel testified under oath, m the

record before this Court, eleven years after Witherspoon, and

his opinion on the current "problem" of nullification --in

light of Witherspoon and in light of the recent post-Witherspoon

research — is unmistakable: "But I want to just reaffirm t e

point that whatever this proportion of people is who might

pervert the issue of guilt, they are neither at issue in this

law court nor at issue in any one of the later studies.

(Hovey Tr. 220 ) . 30

At bottom the State is arguing that jurors who state

that they would not consider voting for the death penalty in any

case cannot be trusted to be fair and impartial in deciding

guilt or innocence in a capital case, even though they state

under oath, after searching cross-examination, that they would

be fair and impartial on that issue. (Atty. Gen. Br., 20-33).

This is an argument that has no boundaries.

It may be true that some jurors who promise impartiality

will not act accordingly, but that fact applies to jurors

throughout the entire spectrum of death penalty attitudes. Would

it not be safer to exclude all opponents of the death penalty

from capital cases on the ground that some of them may deceive

the court, either intentionally or unintentionally, about their

ability to consider voting for death and to be fair and impartial?

And on the other side, why not be safe and exclude all strong

proponents of capital punishment, since some of them may be

unable to try guilt impartially, but will be unwilling to admit

? If we are concerned about candor, those jurors who forth

rightly state that they will be unwilling to consider the death

penalty — the law of the State notwithstanding — are better

candidates for our trust than many of those who merely say

what is expected of them; after all, any juror who wanted to

get on the jury by stealth could easily deny holding any fixed

views on capital punishment.

Witherspoon holds that no juror can be excluded for

opposition to the death penalty unless that juror himself makes

it "unmistakably clear" that he holds a disqualifying attitude,

observing that "[i]t is entirely possible, of course, that even

31

a juror who believes that capital punishment should never be

inflicted and who is irrevocably committed to its abolition

could nonetheless subordinate his personal views to what he

perceived to be his duty to abide by his oath as a juror and

13/

obey the law of the State," id. at 514-15, n.7. Subsequently,

in Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38 (1980), the Court made the

proper standard for exclusion even plainer; fair and impartial

jurors are entitled in a capital case to take the prospect of

a death sentence into account, and to be influenced by it, so

long as they state that they can obey their oaths.

[T]he Constitution [does not] permit the

exclusion of jurors from the penalty phase

of a Texas murder trial if they aver that

they will honestly find the facts and answer

the questions in the affirmative if they are

convinced beyond a reasonable doubt, but not

otherwise, yet who frankly concede that the

prospects of the death penalty may affect

what their honest judgment of the facts will

be or what they may deem a reasonable doubt.

Such assessments and judgments by jurors are

inherent in the jury system, and to exclude

all jurors who would be in the slightest way

affected by the prospect of the death penalty

or by their views about such a penalty would

be to deprive the defendant of the impartial

jury to which he or she is entitled under

the law.

Id. at 50. In inviting this Court to rule as a matter of law

that a whole class of prospective jurors cannot be trusted,

despite their oaths to the contrary, the State is asking

the Court to ignore the Supreme Court's articulated standard,

13/ This standard is consistent with the general rule that

prospective jurors are presumed to be impartial unless the con

trary is clearly demonstrated. See United States v. Jones, 508

F. 2d 1004, 1007 (4th Cir. 1979); Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717,

723 (1961).

32

in order to preserve a practice that is demonstrably unfair

to capital defendants.

14./ The State cites three cases in support of this argument.

One -- Soinkellink v. Wainwright, supra -- is premised on the

supposition that the uncommonly greater likelihood of death-

qualified juries to convict has no constitutional significance.

As we have argued above, this holding is contrary to logic and

to a clear line of Supreme Court cases, and should be rejected

by this Court as it has been rejected elsewhere. The second

case cited, People v. Ray, 252 Cal. App.2d 932 (1967), is in

apposite for the simple reason that it pre-dates Witherspoon

and reflects the state of California law when there were

virtually no constitutional restrictions on a state's power

to exclude death penalty opponents from capital juries. (The

current state of California law on this issue i s d fscribed

by Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 616 P.2d 1301 (198),

a case which includes a detailed discussion of death-qualifica

tion, but which the State all but ignores. The third_citation

— to McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971) is partic

ularly puzzling. The "unitary trial" question in McGautha

was not who would determine guilt and penalty in capital cases,

but whether a separate penalty hearing was constitutionally

required. McC-autha held that a separate hearing was not re

quired, but its holding was severely undermined if not

effectively reversed — by Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972), and by the long series of Supreme Court cases apply

ing Furman. The State, oddly enough, seems to inte^Pr®^j ̂ he

1976 Supreme Court death penalty cases — Gregg v.— Georgia, ^

428 U.S. 153 (1976); Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976);

and Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976) — as upholding a

unitary procedure for determining guilt and penalty. (

j.A . 78). In fact, bifurcated capital trials (in the McGautha

sense) have been universal since Furman, and a unitary deter

mination of guilt and penalty would probably be held to be

inconsistent with the Eighth Amendment requirements for the

penalty determination under Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586

(1978), if the issue were ever presented to any court.

33

The Value of the Social Scientific Evidenceiv.

a. Attitudes and Behavior, And The Work.

Of Dr. Steven Penrod ______________

The State makes much of a claim that "Petitioners

rely on the view that attitudes affect or cause behavior to

a substantial extent." (Atty. Gen. Br., at 46). Not so.

Attitudes may indeed "cause" behavior to a greater or lesser

extent, but that possibly has little bearing on the legal

claims in this case. Petitioners have demonstrated, exhaustively,

that the attitudes for which Witherspoon-excludable jurors are

excused from service are correlated with (i) other attitudes

that bear intimately on the functions of jurors in criminal

cases, and (ii) the actual voting behavior of criminal trial

jurors. It is irrelevant whether their death penalty attitudes

"cause" these differences between death-qualified and excludable

jurors, or. whether the other differences "cause" the death

penalty attitudes, or whether both are aspects of consistent

overall outlooks. Whatever the causal link, if any, the con

sequences of the exclusionary practice are the same: removal

of Witherspoon excludables disadvantages the defense, and it

aids the prosecution in obtaining convictions. Contrary to the

State's repeated statements (see,e.g., Atty. Gen. Br., 9,11,

14.-19,28), these biasing effects need not be inferred from any

evidence or any assumptions about the relationship between

attitudes and behavior in general; they have been demonstrated

directly by the studies in the record -- six studies documenting

the fact that death-qualified juries are more prone to convict

than ordinary juries and half-a-dozen surveys describing the

differences in outlook between the two groups of jurors.

34

The State relies heavily on a study by Dr. Steven

Penrod (J.A. 324-330; see Atty. Gen. Br., 16-19) which it

describes, variously, as "ambitious research" (Atty. Gen. Br.,

at 19), "extremely important" (id. at 48), and "the only proof

beyond opinion currently available." (Id. at 16). Indeed, the

State goes so far as to claim that Dr. Penrod's study "knocks

the props out from under the petitioners' position. ' (Id.,

16-17). Given this billing, the Penrod study certainly deserves

some comment.

Dr. Penrod recruited volunteers from a Boston jury

pool and had them deliberate on four simulated cases. He then

examined their verdicts and attempted to correlate them with

several attitudes that he measured by administering a questionnaire

to the jurors. He found, with a few exceptions, that the attitudes

that he examined were poor predictors of the jurors' votes. This

is an interesting study, but what bearing does it have on the

issues in the present case? Even at first glance the answer

seems clear: little or none. As the State itself acknowledges

(id. at 18, n .8), Dr. Penrod did not examine the death penalty

attitudes of his subjects. The study provides no direct evidence

on any material issue before this Court.

If that was all there was to be said about Dr. Penrod's

work, it would merely seem that the State had oversold an un

commonly weak argument. The fact that other attitudes are not

correlated with juror behavior would not "knock the props out

from under" the claim that death penalty attitudes are so

correlated, but it might be indirectly and weakly relevant.

But that's not all there is to be said.

35

The State argues that its position is bolstered,

somehow, by the fact that Dr. Penrod's work is unpublished.

(Atty. Gen. Br., at 48). The logic of this argument escapes