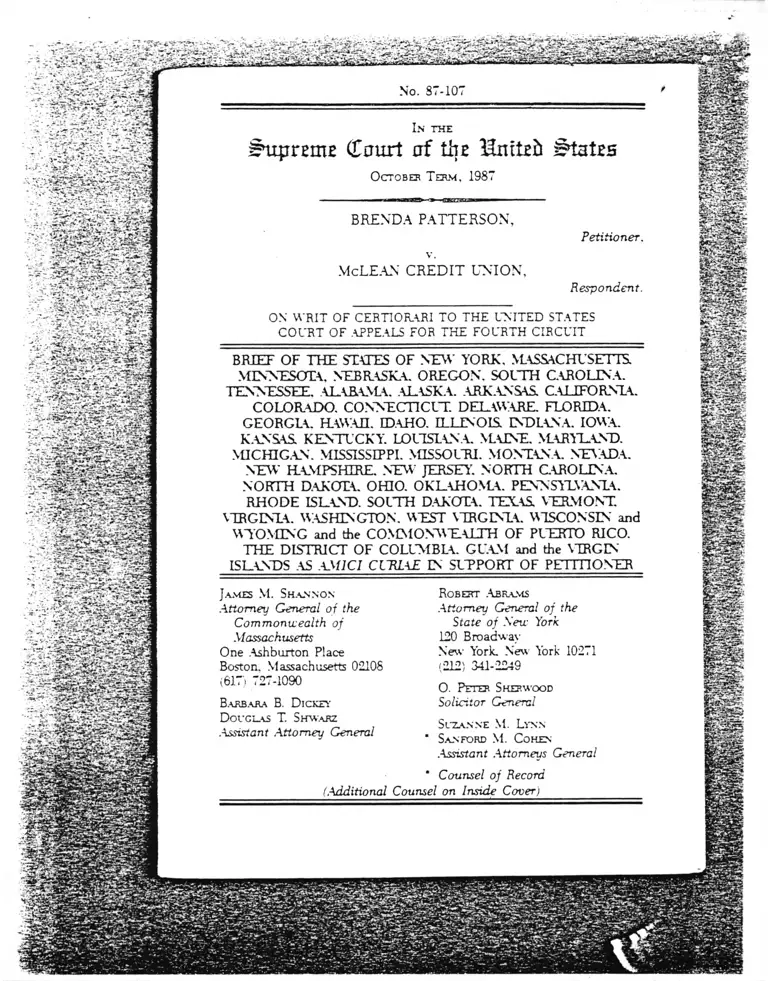

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief of New York and Other States Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 24, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief of New York and Other States Amici Curiae, 1988. 200e8eb8-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7717ca57-a36b-4b59-a539-fbfd9014176d/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-brief-of-new-york-and-other-states-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme CCnurt of the United States

BRENDA PATTERSON

Petitioner

McLEAN CREDIT UNION

Respondent

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF .APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE STATES OF NEW YORK, MASSACHUSETTS,

MINNESOTA. NEBRASKA. OREGON. SOUTH CAROLINA.

TENNESSEE. ALABAMA. .ALASKA. ARKANSAS. C.AITFORNTA.

COLORADO. CONNECTICUT. DELAWARE. FLORIDA.

GEORGLA. HAWAII. IDAHO. ILLIN O IS END LANA. IOWA.

KANSAS KENTUCKY. LOUISIANA. MAINE. MARYLAND.

MICHIGAN. MISSISSIPPI. MISSOURI. MONTANA. NEVADA.

NEW HAMPSHIRE. NEW JERSEY. NORTH CAROLINA.

NORTH DAKOTA. OHIO. OKLAHOMA. PENNSYLVANIA.

RHODE ISLAND. SOUTH DAKOTA. TEXAS VERMONT

VIRGINIA. WASHINGTON. WEST VIRGINIA. WISCONSIN and

WTO MENG and the COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO.

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA. GUAM and the VIRGIN

ISLANDS .AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

J ames M. Shannon

Attorney General of the

Commonieealth of

Massachusetts

One .Ashburton Place

Boston. Massachusetts 02108

Robert .Abrams

Attorney General of the

State of Seu• York

120 Broadway

New York. New York 10271

(212) 341-2249

O. Peter Sherwood

Solicitor GeneralBarbara B. D ickey

Douglas T. Shwarz

.Assistant Attorney General S u za n n e Nl. L ynn

Sanford M. C ohen

.Assistant Attorneys General

Counsel of Record

(.additional Counsel on Inside Cover)_________

>

H ubert H. H umphrey, III

Attorney General oj Minnesota

102 State Capitol

St. Paul, Minnesota 55155

(612) 296-6196

Robert M. S pire

Attorney General oj Nebraska

2115 State Capitol

Lincoln, Nebraska 68509

(402) 471-2682

D ave FIroiinmayer

Attorney General oj Oregon

100 Justice Building

Salem, Oregon 97310

(503) 378-6(X)2

T. TViavis M edlock

Attorney General oj

South Carolina

Rernbert Dennis Office Building

1000 Assembly State

Columbia, Smith Carolina 29211

(803) 743-3970

W.J. M ic iia ei. C ody

Attorney General of Tennessee

450 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615) 741-3491

D o n S ie g e l m a n

Attorney General oj Alabama

State House

11 South Union Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36130

(205) 201-7300

G race Berc Sch aible

Attomn/ General of Alaska

Pooch K, State Capitol

tnneau, Alaska 99811

19071 465-3600

J ohn Steven C lark

Attorney General oj Arkansas

201 East Markham,

Heritage West Bldg.

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 371-2007

J ohn Van de R am p

Attorney General oj California

1515 K Street, Suite 511

Sacramento, California 95814

(916) 445-9555

D u a n e Woodard

Attorney General oj Colorado'

1525 Sherman Street -

Second Floor

Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 866-5005

J oseph L iebekman

Attorney General of Conneetieut

Capitol Annex, 30 Trinity Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06106

(203) 566-2026

C harles M. O iierly

Attorney General of Delaware

820 North French Street,

8th Floor

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

(302) 571-3838

Robert Butterwoiiti i

Attorney General of Florida

State Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1050

(904) 487-1963

M ic h a e l J. B o w ers

Attorney General of Georgia

132 Stale Judicial Building

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

(404 ) 656-4585

Warren Price, III

Attorney General oj Hawaii

State Capitol, Room 405

Honolulu, Hawaii 96813

(808) 548-4740

J im J ones

Attorney General oj Idaho

State House ,

Boise, Idaho 83720

(208) 334-2400

N eil F. Haiitigan

Attorney General of Illinois

100 W. Randolph Street, 12 Floor

Chicago, Illinois 60601

(312) 917-3000

L inley K. Pearson

Attorney General oj Indiana

219 State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

(317) 232-6201

TIiomas J. M iller

Attorney General of Iowa

Hoover Building - Second Floor

Des Moines, Iowa 50319

(515) 281-5164

Robert T. Steph an

Attorney General oj Kansas

Judicial Center - Second Floor

Topeka, Kansas 66612

(913) 296-2215

Frederick J. C owan

Attorney General of Kentucky

State Capitol, Room 116

Frankfort, Kentucky 40601

(502) 564-7600

Willia m J. C u ste , J r.

Attorney General of Louisiana

2-3-4 Loyola Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

(504) 568-5575

J am es E. TIerney

Attorney General o j Maine

State House

Augusta, Maine 04330

(207) 289-3661

J. J oseph C urran , J r.

Attorney General oj Maryland

Munsey Building

Calvert and Fayette Streets

Baltimore, Maryland 21202-190

(301) 576-6300

Frank J. Kelley

Attorney General o j Michigan

Law Building

Lansing, Michigan 48913

(517) 373-1110

M ich a el C. Moore

Attorney General of Mississippi

P.O. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi

(601) 359-3680

Willia m L. Webster

Attorney General of Missouri

Supreme Court Bldg.

101 High Street

Jefferson City, Missouri 65102

(314) 751-3321

M ike G ref.ly

Attorney General oj Montana

Justice Building

215 North Sanders

Helena, Montana 59620

(406) 444-2026

B rian Mc K ay

Attorney General oj Nevada

Heroes Memorial Building

Capitol Complex

Carson City, Nevada 89710

(702) 885-4170

Stephen E. M errill

Attorney General oj

New Hampshire

208 State House Annex

Concord, New Hampshire 03301

(603) 271-3658

C ary E dwards

Attoniey General of New Jersey

Richard J. Hughes Justice

Complex, CN080

Trenton, New Jersey 08625

(609) 292-4925

L acy 11. 'R iornduru

Attorney General of

North Carolina

Department of Justice,

2 East Morgan Street

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

(919) 733-3377

N ich o las S paeth

Attorney General oj

North Dakota

Department of Justice

2115 State Capitol

Bismarck, North Dakota 58505

(701) 224-2210

Anthony J. C elerrezzi;, J r.

Attorney General oj Ohio

State Office Tower

30 East Broad Street

Columbus, Ohio 43266-0410

(614) 466-3376

Robert H enry

Attorney General oj Oklahoma

112 State Capitol

Oklahoma City-, Oklahoma 73105

(405) 521-3921

L eRoy S. Z im m erm an

Attorney General oj Pennsylvania

Strawberry Square - 16th Floor

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120

(717) 787-3391

J ames E . O ’N eil

Attorney General oj

Rhode Island

72 Piiie Street

Providence, Rhode Island 02903

(401) 274-4400

ROCERT A. 'Ikl-UNCHUISEN

Attorney General oj

South Dakota

Stale Capitol Building

Pierre, South Dakota 57501

(605) 773-3215

J im M attox

Attornnj General of Texas

Capitol Station, P.O. Box 12548

Austin, 'Iexas 78711

(512) 463-2100

J effrey A mestoy

Attorney General oj Vermont

Pavilion Office Building

Montpelier, Vermont 005602

(802) 828-3171

M ary S ue 'IknitY

Attorney General oj Virginia

101 N. 8th Street - 5th Floor

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 786-2071

Ke n n et h O. E ikenberky

Attorney General oj Washington

Highways-Licenses Building, PB71

Olympia, Washington 98504

(206) 753-6200

C h arles G . B rown

Attorney General of

West Virginia

State Capitol

Charleston, West Virginia 25305

(304) 348-2021

D o n I I anaway

Attornnj General oj Wisconsin

114 East, State Capitol,

P.O. Box 7857

Madison, Wisconsin 53707-7857

(608) 266-1221

J o se ph B. M et h i

Attorney General oj Wyoming

123 State Capitol

Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002

(307) 777-7841

G odfrey R. deC asfro

Acting Attornnj General oj

the Virgin Islands

Department of Law

Norre Gade

U S. Post Office Building,

2nd Floor

St. Thomas, Virgin Islands 00801

(809) 774-5666

Frederick D. C ooke

Corporation Counsel o j the

District o j Columbia

The District Building

1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 727-6252

Hector Rivera-C ruz

Attorney General of Puerto Rict

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 192’

San Juan, Puerto Rico 00902

(809) 721-2900

E liza beth Barrett-Anderson

Attorney General of Guam

Department of Law

238 O’Hara Street

Agana, Guam 96910

(671) 472-6841

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CU RIA E .............................. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................... 2

ARGUMENT:

PRINCIPLES OF STARE DECISIS COUNSEL

THAT THE INTERPRETATION OF 42

U.S.C. § 1981 ADOPTED BY THIS COURT

IN RUNYON V. McCRARY SHOULD NOT

BE RECO N SID ERED ............................................ 3

A. Only the Most Compelling Circumstances

Justify This Court’s Abandonment of Firmly

Established Statutory Precedents Since

Congress is Free to Correct Precedents That

Are Wrong : ..................................................... 3

B. Section 1981 Has Become Part of the Fabric

of Legal Protections Afforded Racial and

Ethnic Minorities Through Its Interpretation

by the Courts, Congress’ Ratification of

That Construction, and Reliance By

Individuals and States ...................................... 8

1. This Court's Decision in Runyon and its

Progeny Have Encouraged a Broad Usage

of Section 1981............................................... 8

2. Congress Has Ratified and Relied Upon

Runyon's Decision That Section 1981

Prohibits Private Racial Discrimination 13

ii

3. Individuals and States Have Relied Upon

Section 1981 to Secure Redress for

Invidious Race Discrimination in its

Myriad Form s.................................................

C. The Considerations Which Allow An

Overruling of Statutory Precedent Do Not

Call For a Reexamination of Runyon 22

1. The Court's Construction of Section 1981

in Runyon is Consistent With a National

Consensus Favoring The Elimination of

Racial Discrimination From All Sectors of

Society ............................................................. 22

2. No Intervening Events Since Runyon

Undermine Its Validity or Make It

Difficult to Apply 24

3. This is Not a Situation in Which the

Court Must Reexamine a Prior

Construction Because Its Application

Works to Deny Substantial Rights 27

Page

CONCLUSION 30

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Albermarle Paper Co. o. Moody, 422 U.S. 407

(1975) .......................................................................... 7

Aleyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421

U.S. 420 (1975) i 15

Allen t>. Amalgamated Transit Union Local, 788,

554 F.2d 876 (8th C ir), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

891 (1977) .................................................................. 16

Andrews t>. Louisville and Nashville R. Co., 406

U.S. 320 (1972)......................................................... 22, 25

Arizona v. Rumsey, 467 U.S. 202 (1984) 4

Avco Corp. t>. Aero Lodge, 735, 390 U.S. 537

(1968).......................................................................... 24

Reauford o. Sisters of Mercy-Province of Detroit,

816 F.2d 1104 (6th Cir. 1987), cert, denied,

108 S. Ct. 259 (1988)................................................. 16

Bendetson t>. Pay son, 534 F. Supp. 539 (D. Mass.

1982)........... ................................................................ 18

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S.

574 (1983) ........ ........................................................12, 22, 24

Boys Market Inc. v. Clerks Union, 398 U.S. 235

(1970).......................................................................... 6» 22,

24, 28

Braden o. 30th Judicial Circuit Court of

Kentucky, 410 U.S. 484 (1973) 22, 28

Cases: Pa8e

IV

Brant Const. Co. v. Lumen Const. Co., 515

N.E.2d 868 (Ind. App. 3 Dist. 1987) .......................... 19

Brown o. Superior Court, 691 P.2d 272 (Cal.

1984) .......................................................................... 23

Burnet v. Coronado Oil ir Gas, 285 U.S. 393

(1932).................................................................................. 4

Calhoun v. Lang, 694 S.W.2d 740 (Mo. App.

1985) .......................................................................... 20

Campbell v. Gadsden School Dust., 534 F.2d 650

(5th Cir. 1976) ................................................................... 16

City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive

Health, Inc., 462 U.S. 416 (1983)....................... 3

City of Minn. v. Richardson, 239 N.W.2d 197

(Minn. 1976)............................................................. 23

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883 )..................... 29

Clairborne u. Illinois Cent. R.R., 583 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 442 U.S. 934

(1979).......................................................................... 16

Cody v. Union Electric, 518 F.2d 978 (8th Cir.

1975)............................................................................ 16

Continental T.V. t>. GTE Sylvania, 433 U.S. 36

(1977)..........................................................................22, 25, 26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) 5

Davis o. County of Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334

(9th Cir. 1977), vacated as moot, 440 U.S. 625

(1979) ........................................................................

Page

16

V

Page

Durham o. Red Lake Fishing <b Hunting Club,

666 F. Supp. 954 (W.D. Tex. 1987)................... 17

Easley o. Anheuser-Busch, Inc., 572 F. Supp. 420

(E.D. Mo. 1983), a ff ’d in part and rev'd in

part, 758 F.2d 251 (8th Cir. 1985) ..................... 16

Eastman Kodak u. Fair Empl. Prac. Com'n., 426

N.E .2d 877 (111. 1981)............................................ 23

Edwards v. Boeing Vertol, 717 F.2d 761 (3d Cir.

1983), vacated on other grounds, 468 U.S. 1201

(1984)................................. 17

Evening Sentinel v. NOW, 357 A.2d 498, 503

(Conn. 1975)............................................................. 23

Florida Dept, of Health v. Florida Nursing

Homes Association, 450 U.S. 147 (1981) 4

Fraser v. Doubleday & Co., Inc., 587 F. Supp.

1284 (S.D.N.Y. 1984)............................................... 18

Fullilove t>. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980)............ 12

General Building Contractors Assn. u.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 100 (1981)....................... 8, 10, 11,

18, 27

Goodman u. Lukens Steel Company, 482 U.S.

____ 107 S. Ct. 2617 (1987).................................... 8 ,1 2 ,

17, 27

Gore o. Turner, 563 F.2d 159 (5th Cir. 1977). 16

Hall v. Bio-Medical Application, Inc., 671 F.2d

300 (8th Cir. 1982).................................................. 18

VI

Hall v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F.2d 86

(3d Cir. 1978)........................................................... 18

Hawthrone v. Realty Syndicate, Inc., 259 S.E.2d

591 (N.C. App. 1979) ........................................... 20

Hernandez o. Erlenhush, 368 F. Supp. 752 (D.

Ore. (1973) ............................................................... 17

Hishon v. King <ir Spaulding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) . 13

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906).......... 29

Howard Sec. Serv. v. Johns Hopkins Hospital,

516 F. Supp. 508 (D. Md. 1981)......................... 18

Hunter v. Allis-Chalmers Corjj., Engine Div., 797

F.2d 1417 (7th Cir. 1986).............. 16

Hyatt Corj). v. Honolulu Liquor Corn'll, 738 P.2d

1205 (Hawaii 1987) ................................................. 23

Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977) . 4

Jackson v. Concord Co., 253 A.2d 793 (N.J.

1968)............................................................................ 23

Jennings o. Patterson, 488 F.2d 436 (5th Cir.

1974 ............................................................................ 18

Jiminez v. Southridge Co-op, Section I, 626 F.

Supp. 732 (E.D.N.Y. 1985).................................... 18

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U.S. 459 (1975)................... ..................................10, 11, 16

Jones o. Alfred II. Mayer, Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968).......................................................................... passim

Page

Kelly v. Robinson, 479 U.S. ___ , 107 S. Ct. 353

(1987) .......................................................................... 9

Kentucky Com’n on Human Rights a. Fraser, 625

S.W.2d 852 (Ky. 1982) .......................................... 23

Knight v. Auciello, 453 F.2d 852 (1st Cir. 1972) . 15

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1971) ......................................................... 15

Lindahl v. OPM, 470 U.S. 748 (1985) ................... 15

Machinists o. Wisconsin Employment Relations

Commission, 427 U.S. 365 (1976) ....................... 22, 25

Mackey e. Nationwide Ins. Companies, 724 F.2d

419 (4th Cir. 1984)................................................... 18

Madison v. Cinema /, 454 N.Y.S.2d 226 (Civil

Court of City of New York, N.Y. Co. 1982) . . . 20

Maine Human Rts. Com’n v. Canadian Pacific,

458 A.2d 1225 (Me. 1983)................................................ 23

Marable v. H. Walker ir Associates, 644 F.2d 390

(5th Cir. 1981) ......................................................... 18

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trial Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976)................................................. 8, 10, 11

McKnight v. General Motors Corp., 420 N.W.2d

370 (Wis. App. 1987)...................................................... 20

McNulty o. Hill, 293 U.S. 131 (1934)..................... 27, 28

vii

Page

VIII

Mdscaro u. Wokocha, 489 So.2d 274 (La. App.

4th Cir. 1986)........................................................... 20

Memphis o. Greene, 451 U.S. 100 (1981)............... 8, 18

Miller v. C.A. Muer Corp., 362 N.W.2d 650

(Mich. 1984) ............................................................. 23

Monell v. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S.

658 (1978) .................................................................. passim

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)..................... 4, 9, 26

Moore v. Sun Oil Co., 636 F.2d 154 (6th Cir.

1980)............................................................................ 17

Moraine v. State Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S.

375(1970) .................................................................. 25

NLRB v. Longshoreman, 473 U.S. 61 (1985).......... 4

Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808 (1984) . . . 7

Olzman t>. Lake Hills Swim Club, Inc., 495 F.2d

1333 (2d Cir. 1974) ................................................. 17

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, ____U.S.

_________ S.C t_____ ., (April 25, 1988) ............. 7, 28

Penn. Human Bel Com’n v. Chester School Dust.,

233 A.2d 290 (Pa. 1967) ........................................ 23

People of the State of New York v. Data-

ButterficlJ Inc., Civ. Action No. CV-80-365

{E.D.N.Y )

Page

19

Page

People of the State of New York o. LaBosa

Realty, Inc., Civ. Action No. CV-85-4459

(E .D .N .Y .).................................................................. 19

People of the State of New York v. Mahler

Realty, Civ. Action No. CV-85-4460 19

People of the State of New York v. Merlino, 88

Civ. 3133 (S .D .N .Y .).............................................. I9

Peyton v. Rowe, 391 U.S. 54 (1968)....................... 22, 27, 28

Phelps n. Washburn University of Topeka, 632 F.

Supp. 455 (D. Kansas 1986) 17

Phonetele v. ATT, 664 F.2d 716 (9th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1145 (1983) 3

Plessy o. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) 23

Quarles v. GMC (Motor Holding Div.), 758 F.2d

839 (2d Cir. 1985) ................................................... 18

Quinones v. Nescie, 110 F.R.D. 346 (E.D.N.Y.

1986)............................................................................ I8

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967)............... 7

Riley v. Adirondack Sch. for Girls, 541 F.2d 1124

(5th Cir. 1976) ......................................................... 17

Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609

(1984).......................................................................... I2

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) passim

X

St. Francis College o. Al-Khazraji, 481 U .S .----- ,

107 S.Ct. 2022 (1987) ............................................ 8, 10,

12, 27

Saunders v. General Services Corp., 659 F. Supp.

1042 (E.D. Va. 1986)............................................... 18

Scott v. Young, 421 F.2d 143 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 398 U.S. 929 (1970).................................. 17

Setser v. Novack Inv. Co., 638 F.2d 1137 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1064 (1981) 17

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 481 U.S.

___ , 107 S. Ct. 2019 (1987).................................. . 8

Page

Sims v. Order of United Commercials Travelers of

America, 343 F. Supp. 112 (D. Mass. 1972) 18

Sinclair Refining Company u. Atkinson, 370 U.S.

195 (1962) .................................................................. 24, 25

Smith t>. United Technologies, Essex Group, 731

P.2d 871 (Kan. 1987) » .................................. 19

Solem v. Helm, 467 U.S. 277 (1983)....................... 3

Spann v. Colonial Village Inc., 662 F. Supp. 541

(D.D.C. 1987)........................................................... 18

Spencer v. McCarley Moving b Storage, 330

S.E.2d 753 (Ga. App. 1985).................................. 20

Square D. Company and Rig D Building Supply

Corf), v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau, 106

S. Ct. 1922 (1986) .............................................. 4

xi

Stallworth o. Shuler, 111 F.2d 1431 (11th Cir.

1985)............................................................................ 16

Sud v. Import Motors Limited, Inc., 379 F.

Supp. 1064 (W.D. Mich. 1974) ........................... 18

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S.

229 (1969) .................................................................. 6, 8,

17, 19

Taylor v. Flint Osteopathic Hosp. Inc., 561 F.

Supp. 1152 (E.D. Mich. 1983)........................................ 18

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Assn., 410

U.S. 431 (1973)......................................................... 6, 8, 10

United States v. Arnold, Schwinn b Co., 388

U.S. 265 (1967)................................................................ 26

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S.

258 (1947) ................................ 5

Vasques v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254 (1986)................. 7

Vietnamese, Etc. v. Knights of K .K.K., 518 F.

Supp. 993 (S.D. Tex. 1981).............................................. 18

Williams u. Trans World Airlines, 660 F.2d 1267

(8th Cir. 1981) ................................................................ 16

Wright u. Salisbury Club, LTD, 432 F.2d 309

(4th Cir. 1980) ................................................................ 17

Wyatt v. Security Inn Food b Beverage, Inc.,

819 F.2d 69 (4th Cir. 1987)

Page

17

XII

United States Constitution:

Amend. XIII .................................................................. 10’ 11

Amend. XIV .................................................................. 10

Federal Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1866 6, 9,

13, 20

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII passim

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976. 14

Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, P.L.

100-255, 102 Stat. 28 (March 22, 1988) 24

Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 13, 14

15 U.S.C. § 1691 (e)(i) ................................................. 14

28 U.S.C. § 453 ........................................................... 29

28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(3)................................................. 27

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ......................................................... Passim

42 U.S.C. 5 1982 ......................................................... 6’ l,)’ 15

42 U.S.C. § 1983 . ........................................................ 26

42 U.S.C. § 1988 14

42 U.S.C. 1) 2000a 3 17

Ul U S C. \ 20O0e-5tei * '

4^ i p .n v. ;j 3t 10-

Page

State Statutes, Regulations and Executive Orders:

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 41-1461 (1982)................... 20

Cal. Civil Code § 52.1 (West 1988) 19

Cal. Covt. Code 5 12926 (West 1986) 21

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 46a-51 (West 1986) 21

Del. Code Ann. till. 19, § 710 (1985) 21

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 760.02 (West 1985) 20

Idaho Code § 67-5902 (Supp. 1987) 21

111. Ann. Stat. ch. 68, para. 2-101 (Smith-Hurd

1987)............................................................................ 20

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 44-111 (1986) 21

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 344.030 (Michie 1983) 21

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 23:1006 (West 1985) 2C

Md. Ann. Code art. 49B, § 15 (1986) 21

Mass. Exec. Order No. 237, Mass. Admin. Reg.

509 (1984) ................................................................. 1£

Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. Ch. 12 § 11H, 111, 11J . • H

Mass Gen Lau Ann Cb 23A f 39-44 West

S^pp i >8: J f

Mass. Gen. L. ch. 151B § 1 (1986)......................... 21

Page

XIV

Page

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 213.010 (Vernon 1980)............... 21

Neb. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 48-1101 (1984)................... 23

Neb. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 48-1102 (1984)................... 21

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 613.30 (Michie 1986) ................. 21

N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 354-Ai3 (1984)................... 21

N.M. Stat. Ann. (j 38 1-2 (Supp. 1986)................... 21

N.Y. Exec. Law § 290 (McKinney 1982) ............... 23

N.Y. Exec. Law § 292 (McKinney 1982) ............... 21

N.Y. Exec. Order 21 (1983) ...................................... 19

N.Y. Pub. Auth. Law § 1766-c 14(a)(1)

(McKinney 1986)....................................................... 19

N.Y. Transp. Law tj 428(2) (McKinney 1983) . . . . 19

N.Y. Unconsol. Laws § 6267 (McKinney 1983) . . . 19

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 143-422.1 (19831......................... 20

N D Cent Co*4e chapt. 14-02.4 21

Ohio Ke\ C .vie Ann t, 4112 o l a 2 Anaersor.

v v -

XV

Page

S.C. Code Ann. § 1-13-20 (Law Co-op 1986) . . . . 23

S.C. Code Ann. § 1-13-30 (Law Co-op 1986) . . . . 21

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-101 (1985) ....................... 23

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-102 (1985) ....................... 21

Texas Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. art. 5221K (Vernon

1987)............................................................................ 21

Utah Code Ann. § 34-35-2 (1988) ........................... 21

Va. Code Ann. § 2.1-714 (1987) .............................. 20

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 49.60.040 (1967) .......... 21

W. Va. Code § 5-1 l-3(d) (1987) ............................. 21

Other Authorities:

B. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process

149 (1921) .................................................................. 22

Comment, Development in the Law —Section

1981, 15 Harv. Civ. Rights —Civ. Lib. L. Rev.

29 (1980) .................................................................... 27

Douglas, Stare Decisis, 49 Colum. L. Rev. 735

(1949) ..........................................................................

3 Employ. Prac. Guide (CCH) 11 20,098, 20,698

21.898. 24.698

XVI

Page

Pound, The Future of the Law, 47 Yale L. J. 1 ,

(1937) .................................................................................. 5

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

reprinted at 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News 5908 .................................................................. 15

Wachtler, Stare Decisis and a Changing New

York Court of Appeals, 59 St. John’s L. Rev.

445 (1985) .......................................................................... 5

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici respectfully submit this brief in support of petitioner

Patterson. Amici urge this Court to decline to re-examine Ru

nyon v. McCrary, and thus reaffirm that § 1981 reaches private

discriminatory conduct.

The eradication of racial discrimination remains a national

goal of the highest order. Amici are the Attorneys General of forty-

seven states and of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands,

and the highest legal officer of the District of Columbia. As chief

law enforcement officers and representatives of government, amici

have a strong interest in encouraging the perception of all their

citizens that the laws will lie administered with even-handedness,

and particularly their minority citizens’ belief that they can obtain

meaningful redress under the law for discriminatory conduct.

Moreover, States have an interest in the confidence of their citizens

that once a rule of law is in place it will not be taken away ab

sent compelling justification. This interest applies with particular

force to the civil rights laws, which are properly characterized

as conferring on minority citizens fundamental equality under

law which was previously available only to white citizens. Over

ruling Runyon would remove substantial protections, thereby

undermining public confidence that government — particular

ly the courts — will vigilantly enforce legal guarantees of equality.

The substantial progress made in overcoming this Nation’s legacy

of slavery has l>een achieved in large part because of the aggressive

use by victims of discrimination of federal and state laws gviaranteeing

equality. Removing § 1981, the Nation’s first civil rights law, from

the array of available legal remedies for private discrimination could

undermine this progress since state laws depend for their full effec

tiveness on their interaction with, and complementing of, federal

law. The gap in available remedies which would be created by over

ruling Runyon would have to be filled by over forty individual States,

and while ultimately it could be achieved, confusion and chaos would

be the likely immediate result.

The citizens of this country have come to agree that no place

exists for racism in the American marketplace Private discrimina

tion, unredressable by law, corrodes the body politic just as surely

2

as did publicly sanctioned discrimination in decades past. Amici

submit that no compelling reason exists for overruling Runyon

and that such a reversal would conflict with the prevailing sense

of justice in this nation.

The States of New York and Massachusetts, by Attorneys

General Robert Abrams and James M. Shannon, joined by Min

nesota, Nebraska, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama,

Alaska, Arkaasas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware,

Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kan

sas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississip

pi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey,

North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania,

Rhode Island, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Virginia,

Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Puerto Rico,

the District of Columbia, Guam and the Virgin Islands as amici

submit this brief pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 36.4.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

For two decades it has been clear that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 pro

hibits private discrimination on the basis of race in the making

of contracts. Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976), reaffirm

ed the considered views of thisand other courts that Congress

intended tj 1981 to reach private acts of discrimination.

1 hough neither the parties to this action nor the Solicitor

General bad urged a reexaminination of Runyon, this Court sua

sponte has suggested that the protections against racial, ethnic

and religions discrimination that <j 1981 affords might be discard

ed. Embarking on this course could cause substantial institutional

and societal injury Ixx.ause, until now, the law of § 1981 has been

settled to the satisfaction of the people as expressed by their elected

officials and no compelling reason has appeared to upset it.

Section 1981 provides an array of remedies not available under

other federal laws that bolster the efforts by governments and

individuals to eradicate racial discrimination in wide ranging cir

cumstances. Encouraged by the Court’s broad reading of § 1981,

ami Congresss endorsement of the Court’s construction, in

dividuals and States have so frequently relied upon its protec

tions that it is now a part of our legal fabric.

3

Adherence to the settled interpretation of the statute conforms

with the national commitment to the eradication of invidious

discrimination. Overruling it would cause unnecessary chaos and

frustrate justified expectations. None of the considerations which

have compelled the Court in prior cases to depart from a settled

statutory interpretation suggests that Runyon needs reexamina

tion. In order to conserve efforts dedicated to thwarting racial

discrimination and to preserve the citizens’ confidence that this

is a nation of laws, this Court should not reconsider Runyon.

ARGUMENT

PRINCIPLES OF STARE DECISIS COUNSEL THAI

THE INTERPRETATION OF 42 U.S.C. § 1981

ADOPTED RY THIS COURT IN RUNYON V.

McCIbKRY SHOULD NOr BE RECONSIDERED

A. Only the Most Compelling Circumstances Justify Thus

Court’s Abandonment of Firmly Established Statutory

Precedents Since Congress Is Free to Correct Precedents

That Are Wrong

Prompted neither by the arguments of any party to this case

nor by any pressing doctrinal or social exigency, this Court has

asked whether a settled construction of a civil rights statute should

be re-examined and jettisoned. Although amici are satisfied that

a fresh look at the plain words of the act and at the historical

context and legislative debates surrounding its adoption would

compel the conclusion that § 1981 reaches private discriminatory

conduct, we urge that the injury to society and the judicial system

that are likely to attend a reconsideration counsel that this Court

should not entertain the inquiry.

“[I ]n a society governed by the rule of law,” the doctrine of

stare decisis “demands respect.” Salem t>. Helm, 467 U.S. 277, 311

(1983) (Burger, C.J., dissenting), quoting City of Akron v. Akron

Center for Rejnvductive Health, Inc., 462 U.S. 416, 419-20 (1983)^

See also Phonetele o. ATT, 664 F.2d 716, 753 (9th Cir. 1981), cert,

denied, 459 U.S. 1145 (1983) (Kennedy, J., dissenting) (“[W]e are

first and foremost a nation of laws and the principle of stare decisis

is the single most important key to the cohesiveness of our socie

ty.”) Even as to constitutional questions, “any departure from the

4

doctrine of stare decisis demands special justification.” Arizona

v. Iiuinsey, 467 U.S. 202, 212 (1984) (per O'Connor, J.)

Moreover, the Court has repeatedly recognized that “considera

tions of stare decisis are at their strongest when tills Court con

fronts its previous construction of legislation.” Monell v. Depart

ment of Social Sendees, 436 U.S. 658, 714 (1978) (Rehnquist, J.,

dissenting). Indeed, “in most matters it is more important that

the applicable rule of law be settled than that it be settled right.”

Unmet v. Coronado Oil <b Gas, 285 U.S. 393, 406 (1932) (Brandels,

J., dissenting). And considerations of stare decisis weigh most

“heavily in the area of statutory construction, where Congress is

free to change this Court’s interpretation of its legislation.” Illinois

Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720, 7.36 (1977) (per White, J.). Thus,

only recently this Court reiterated that there Is a “strong presump

tion of continued validity that adheres in the judicial interpreta

tion of a statute” Square D Company and Big D Building Supp

ly Corj). v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau, 106 S. Ct. 1922, 1930

(1986). See also NLRB v. Longshoreman, 473 U.S. 61, 84 (198,5).

In order to overcome the presumption, it must “appear beyond

doubt that the Court s earlier interpretations “misapprehended

the meaning of the controlling provision, before a departure from

what was decided in those cases would be justified.” Monroe v.

Tape, 365 U.S. 167, 192 (1961) (Harlan, J., concurring). See also

Monell v. Dej)t. of Social Services, 436 U.S. at 715 (Rehnquist,

J., dissenting) ( adopting Justice Harlan’s standard as “the best

exposition of the projwr burden of persuasion" and stating “[ojnly

the most compelling circumstances can justify this Court’s aban

donment of ... firmly established statutory precedents”)

These guideposts serve important institutional and societal im

peratives. Adhering to stare decisis makes it possible for “citizens

[to] have confidence that the rules on which they rely in order

ing their affairs ..., are rules of law and not merely the opinions

of a small group of men who temporarily occupy high office.”

blorula Department of Health v. Florida Nursing Homes Associa

tion, 450 U.S. 147, 154 (1981) (Stevens, J., concurring). Projjer

resjtect for this Court s judgments depends as much upon the ap-

[)earance that they are rooted in impartial decisionmaking as ujxm

a conviction that they are correct in an abstract sense. Giving

5

consideration to reversing the construction of a frequendy invok

ed civil rights statute in circumstances where the personnel of the

Court, and little else, has changed can undermine the esteem in

which the public holds the judiciary.1 The need for careful preser

vation of the confidence of citizens in the functions and processes

of the Court can never be underestimated. Recent history teaches

us that when Uiose outside die Court seek to undermine that con

fidence, constitutional confrontations and social chaos will beset

us. See e.g. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).2

Continued devotion to a settled statutory construction also en

sures that the Court acts properly within its sphere of powers.

When the Court considers overruling its coastruction of a statute,

it deals with a coordinate and majoritarian branch of govern

ment. That it mast when called upon interpret a statute is beyond

question. But once it so acts, it should lie cautious not to encroach

upon legislative functions vested in Congress by Article I of the

1 Because the five member majority voting to reconsider Runyon is comprised

of Runyon's dissenters and the three members to join the Court since then, the

decision in this case is especially noteworthy. The principles of stare decisis are

therefore particularly com|>elling here See generally Wachtler, Stare Decisis

and a Changing New York Court of Appeals, 59 St. John's L. Rev. 445 (1985).

’ The rule of law, and not of men, is the very foundation of our constitutional

government and it is to the judiciary that its preservation has been entrusted.

[T]he Founders knew that law alone saves a society from being rent

by internecine strife or ruled by mere brute power however disguis

ed. “Civilization involves subjection of force to reason and the agen

cy of this subjection is law." (Round, The Future of the Law (1937)

47 Yale L. J. 1, 13.) The conception of a government by laws

dominated the thoughts of those who founded this nation and

designed its Constitution ... To that end, they set apart a body of

men, who were to l)e the depositories of law, who by their disciplin

ed training and character and by withdrawal from the usual temp

tations of private interest may reasonably be expected to be “as free,

impartial, and inde|>endent as the lot of humanity will admit.” So

strongly were the framers of the Constitution bent on securing a

reign of law that they endowed the judicial office with extraor

dinary safeguard and prestige.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. at 23-24 (Frankfurter, J., concurring) quoting United

Stair’s v. United Aline Workers, 330 U.S. 258, 307-309 (1947) (concurring opinion).

6

Constitution.3 When, as here, the Congress has ratified the in

terpretation this Court has placed upon a statute (See Part (B)

(2) post), the Court, rather than challenging Congress to act

again, should adhere to precedent. Boys Market v. Clerks Union,

398 U.S. at 258-259; Monell u. Dept, of Social Services, 436 U.S.

at 716-17 (Ilehnquist, J., dissenting).

Finally, abjuring the opjxjrtunity to recoasider long held views

about the reach of a statute removes doubts about the continued

vitality of other decisions construing similar statutory commands.

Certainly, a reversal of the Court’s views in Runyon v. McCrary,

given the analysis the Court there employed in eoastruing § 1981/

could cast doubt on the continued validity of its interpretation

of <j 1982 in Jones v. Alfred //. Mayer, Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968),

and Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Awn., 410 U.S 431

(1973).

Interpreting and determining the reach of a civil rights statute,

like adjudication of rights secured by the Constitution, often re

quires the Court to undertake difficult redefinitions and line

drawing, tasks that certainly confront the Court in this case as

it first appeared here. But, settled rights cannot be jettisoned

merely because their vindication in varying factual settings may * I

’ As Justice Black observed in his dissenting opinion in Roys Markets v. Clerks

Union, 308 U.S. 235, 258 (1070):

[l]t is Congress, not this Court that is elected by the people. This

Court should ... interject itself as little as [rossible into the law

making and law-changing process. Having given our view on the

meaning of a statute, our task is concluded, absent extraordinary

circumstances. When the Court changes its mind years later, simply

I recause the judges have changed, in my judgment it takes upon

itself the function of the legislature

* In Runyon, the Court observed that the view that § 1081 does not reach private

acts of discrimination “is wholly inconsistent with Jones’ interpretation of the

legislative history of § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of I8(i<), an interpretation that

was reaffirmed in Sullivan v. I Mile lluntin g I’ark, Inc., 3! Mi U.S. 220, and again

in Tillman v. Wheaton-llaven Recreation Assn., supra. And this consistent in

terpretation of the law necessarily requires that tj 1081, like tj 1082, reaches

private conduct.” 427 U.S. at 173.

7

be difficult/ Were this Court to retract its decisions in every case

involving difficult statutory construction, it would introduce in

tolerable uncertainty not only into civil rights law, but into all

our affairs. Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808, 819 n.5 (1984)

(“The principle of stare decisis gives rise to and supports ...

legitimate expectations, and where our decision is subject to cor

rection by Congress, we do a great disservice when we subvert

these concerns and maintain the law in a state of flux.")/ In a

nation founded on the institutions of slavery and dedicated only

in the last generation to a policy that would “eliminate so far

as possible the last vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious

page in this country’s history,” Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975), a retreat from settled practices could

be a particularly significant signal for new disorder.

Nothing in this Court’s April 25, 1988 order suggests that the

Court will be unmindful of the interests served by stare decisis.

Patterson v. McLean Credit'Union, ____ U.S. ____(April 25,

1988) (per curium). Thus, those who would propose a detour

“from the straight path of stare decisis” in this case bear the “heavy

burden” of demonstrating “that changes in society or in the laws

dictate that the values served by stare decisis yield in favor of

a greater objective” Vasques v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254, 266 (1986).

While there are circumstances where the need for consistency

in the application of the law and stability in society call for a * *

* Indeed, in another context this Court endorsed the view that the withdrawal

of protection accorded by statute against private discriminatory conduct was

an encouragement to discriminate that violated rights secured by the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Reitman o. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369

(1967).

* See also, Douglas, Stare Decisis, 49 Coluin. L. Rev. 735-36 (1949):

Uniformity and continuity in law are necessary to many activities.

If they are not present, the integrity of contracts, wills, conveyances

and securities will be impaired. And there will Ire no equal justice

under law if a negligence rule is applied in the morning but not

in the afternoon. Stare decisis provides some moorings so that men

may trade and arrange their affairs with confidence Stare decisis

serves to take the capricious element out of law and to give stabili

ty to a society. It is a strong tie which the future has to the past.

8

departure from stare decisis, careful observation leads amici to

the conclusion that the application of § 1981 to private

discriminatory conduct neither conflicts with national policies

nor injects any irreconcilable doctrinal conflicts into the law sug

gesting that Runyon v. McCrary needs reexamination.

B. Section 1981 Has Become Part of the Fabric of Legal Pro

tections Afforded Racial and Ethnic Minorities Through Its

Interjnetation by the Courts, Congress’ Ratification of that

Construction, and Reliance By Individuals and States

1. Thus Court’s Decisions in Runyon and its Progeny Have

Encouraged a Broad Usage of Section 1981.

On at least five occasions’ in the last twelve years, this Court

has been called upon to give meaning to section 1981." None of

those cases has signalled a retreat from the determination in Ru

nyon that (j 1981 reaches all intentional racial discrimination,

public and private, that interferes with the right to contract.

Rather, the Court has consistently stood by that decision and,

by applying it in varying circumstances, underscored its broad

applicability.”

The Court’s opinions in Jones v. Alfred 11. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968) and Runyon v. McCrary, All U.S. 160 (1976) *

’ Goodman v. L uketis Steel Company, 482 U.S. ___ , 107 S. Cl. 2617 (1987);

St. Fmtuis Collete v. Al-Khazruji, 481 U.S_____ 107 S. Cl. 2022 (1987); General

Building Contractors Assn. o. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 100 (1981); McDonald v.

Santa Fe 7bail Thinsportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976); linn yon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160 (1976).

' 42 U.S.C. 5 1981 stales, inter alia:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have

the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts, ... as is enjoyed by white citizens ...

* At the same time, the Court has never departed from its determination reach

ed in Jones v. Alfred It. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), that § 1982, the statutory

twin of § 1981, reaches private discriminatory interferences with property rights.

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, 481 U.S.___ , 107 S. Ct. 2019 (1987); Mem

phis o. Greene, 451 U.S. 100 (1981); Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven llecreation Assn.,

410 U.S. 431 (1973); Sullivan v. tattle //anting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969).

9

demonstrate, based upon the language of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and

its legislative history, that the statute prohibits private discrimina

tion in the making of contracts. While the States leave the full

exposition of that argument to the Petitioner, we urge the Court

to stand by that conclusion. Indeed, each of the questions

necessary to the holding that § 1981 reaches private conduct has

been “ ‘considered maturely and recently’ by this Court,” Monell

t>. Dept, of Social Services, 436 U.S. at 714 (Rehnquist, J., dissen

ting) quoting Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. at 186 (Powell, ].,

concurring).10

First, the Court in recent times has never intimated that the

language of § 1981 indicates a congressional intent to allow private

discrimination. The touchstone of statutory interpretation has

always been the statute itself. E.g., Kelly v. Robinson, 479 U.S.

___ , ____, 107 S. Ct. 353, 358 (1987). In discussing the statute

from which section 1981 is derived, the Court has twice stated

“that the ‘[1866] Act was designed to do just what its terms sug

gest: to prohibit all racial discrimination, whether or not under

color of law ...’ ” Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. at 170 quoting

Jones u. Alfred II. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. at 436 (emphasis add

ed). A fresh look at the statute does not alter the conclusion that

its plain terms do not limit its reach to state action."

“ In Monell, an important reason for the Court's holding that the high burden

for overruling statutory precedent had been met was that in no prior case had

there been a “full airing of all the relevant considerations." Id. at 709 n.6 (Pbwell,

J. concurring). While Justice Rehmpiist argued that stare decisis indicated that

the Court should follow Monroe v. Pape, he did not dispute that the issue had

never been fully canvassed. Rather, he contended that other concerns of stare

decisis predominated. Id. at 718. In contrast, tire history of both the Act of 1866,

as reenacted in 1870 and codified in 1874, and its constitutional girders, received

extensive treatment by the majorities and dissenters in Jones and Bunyon in

formed not only by the analysis of the parties but also by sixteen amici briefs,

including the United States'.

“ Justice White's dissent in Bunyon obviously reads the statute differently. While

he provides support for much of his opinion, his assertion about the language

of section 1981 that “what it says'' does "no more" than "outlaw[] any legal rule

disabling any person from making or enforcing a contract, but does not pro

hibit private racially motivated refusals to contract,” Bunyon v. McCrary, 427

(footnote continued)

10

Second, the Court has concluded that it was the intent of the

Congress that <j 1981 reach both private and public racial

discrimination in the making of contracts. Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. at 169-171; Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 459, 460-61; 465-66 (1975); Tilhnan v. Wheaton-Haven

Recreation Assn, 410 U.S. at 439-40 and n.ll. The legislative in

tent holding has been based upon the plenary review of the

historical materials by the Court in Jones v. Alfred //. Mayer

Co., 392 U.S. at 422-37. See, e.g., Runyon o. McCrary, 427 U.S.

at 170-72. The Court’s reliance on Jones’ careful consideration

of the legislative history is appropriate, once the origin of 5 1981

in the 1866 Act is accepted, since §<j 1981 and 1982 were section

1 of the very same Civil Rights Act of 1866. It is therefore clear

ly not “beyond doubt” based on the legislative history that prior

decisions have been wrong about section 1981. Runyon o.

McCrary, 427 U.S. at 168-70 and n.8; McDonald v. Santa Fe Trial

Transportation Co., 427 U.S. at 286; Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven

Recreation Assn, 410 U.S. at 439; Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. at 422 n.28, 441 n.78; see St. Francis College v. Al-

Khazraji, 107 S. Ct. at 2027; General Rldg. Contractors Ass n

v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. at 390 n.17.

Third, the Court has carefully considered whether § 1981 was

enacted pursuant to the Thirteenth or the Fourteenth Amend

ment and concluded “that section 1981, because it is derived in

part from the 1866 Act, has roots in the Thirteenth as well as

the Fourteenth Amendment.” General Rldg. Contractors A.ss’n

v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375, 390 n.17 (1982); Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. at 168 n.8; Id. at 190 (Stevens, J., concurr

ing); Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. at 441 n.78; see

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass’n, Inc., 410 U.S. at

439-40. I hat conclusion has been based on a comprehensive

U.S. at l!)5 (White, J., dissenting), is conclusionary and, at most, points only

to an ambiguity in that language. See Jones v. Alfred II Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

at 421-425. Surely the Hecoastruction era Congress that enacted § 1981, at least,

intended to thwart any attempt to reimpose slavery in any guise. It would have

c*[*x;ted this broadly worded statute to reach refusals to employ any of the newly

freed slaws unless they agrt*d to conditions of employment that mirrored their

prior condition of servitude.

11

review of the relevant historical materials regarding the origins

of tj 1981. B

Fourth, the Court has been clear, at least since Jones, “ ‘that

the power vested in Congress to enforce [the Thirteenth Amend

ment] by appropriate legislation'... includes the power to enact

laws ‘direct and primary, operating upon the acts of individuals,

whether sanctioned by state legislation or not.’ ” Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. at 179 quoting Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. at 438 (citation omitted).

In the course of examining the legislative and constitutional

underpinnings of § 1981, the Court has applied it expansively

to permit its use as a remedy for private discrimination in a wide

array of circumstances. Even before the Court decided in Ru

nyon that tj 1981 can be invoked to redress a race-based denial

of admission by a private, commercial, non-sectarian school, all

nine members then on the Court agreed that the statute reaches

private refusals to enter into employment contracts. Johnson u.

Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. at 459 (per Blackmun, J., joined

by Burger, C. J. and Stewart, White, Powell and Rehnquist, J.J.)

( “(1 Jt is well settled among the Federal Courts of Appeals - and

we now join them - that § 1981 affords a federal remedy against

discrimination in private employment on the basis of race”);

468-76 (Marshall, ]. joined by Douglas and Brennan, J. J., con

curring in part and dissenting in part). In McDonald v. Santa

Fe Trails Transj). Co., the Court embraced the conclusion that

white persons, like blacks, can invoke its protections because “the

Act was meant ... to proscribe discrimination in the making or

enforcement of contracts against, or in favor of, any race.” 427

U.S. at 295. Four years later, every member of the Court con

sidering whether a claim under § 1981 requires a demonstration

of discriminatory intent agreed that the prohibitions of § 1981

encompass private as well as governmental action" motivated

by race General Building Contractors Assn. v. Pennsylvania, 458

U.S. at 387-88 (per Rehnquist, ]., joined by Burger, C. J., and

White, Blackmun, Powell, O'Connor and Stevens, J.J.); 403-05

(O’Connor, J., concurring); 405-06 (Stevens, J., concurring);

407-418 (Marshall, J., joined by Brennan, J., dissenting).

12

Only last term, the Court was unanimous that § 1981 forbids

all racial discrimination in the making of private contracts when

“[b]ased on the history of § 1981” it had “little trouble in con

cluding that Congress intended to protect from discrimination

identifiable classes of persons who are subjected to intentional

discrimination solely because of their ancestry or ethnic

characteristics.” St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, 481 U.S. at

____, 107 S. Ct. at 2028. And again, several weeks later, no Justice

disagreed with the conclusion of the plurality in a union member

ship case that “a collective bargaining agent could not, without

violating ... § 1981, follow a policy of refusing to file grievable

racial discrimination claims however strong they might be and

however sure the agent was that the employer was discriminating

against blacks.” Goodman o. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. a t ____,

107 S. Ct. at 2625.u

In addition to giving § 1981 an extensive substantive reach,

the Court has woven Runyon into other, related areas of law.

Thus, when the Court held that a private college that engages

in racial discrimination cannot claim a charitable exemption from

tax laws because “racial discrimination in education violates a

most fundamental national policy”, it relied on Runyon and other

cases. Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574, 594

(1983). Similarly, Justices relied on Runyon's recognition that Con

gress enacted tj 1981 pursuant to its powers under the Thirteenth

Amendment when sustaining congressional action requiring set-

asides for minority business enterprises in federally funded con

struction programs. See Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 500

(1980) (Powell, J., concurring). And, Runyon's holding that Con

gress has prohibited private discrimination supports the Court’s

decisions that those who would discriminate in private relations

can find no refuge in the Constitution from other legislation for

bidding such conduct. F.g. Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468

u Those Justices who dissented from the Court’s judgment in Goodman holding

the union liable for racial refusals to process grievances did so not because of

any expressed doubt that § l!)81 encompasses such a claim but lrecau.se on the

record presented they could not conclude that the union intended to discriminate

against black mernlters. Id., 182 U.S. a t ___ , 107 S. Ct. at 2633-34 (Powell,

J., joined try Scalia and O’Connor, J.J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

13

U.S. 609, 628 (1984); Hishon d. King tr Spaulding, 467 U.S. 69,

78 (1984). Embarking on an effort to discern anew the intent

of Congress 120 years ago would call into question the legitimacy

of rights and remedies recently upheld by this Court in some of

its most significant decisions.

2. Congress Has Ratified And Relied Upon Runyon’s Deci

sion That Section 1981 Prohibits Private Racial

Discrimination.

It Is now familiar history, chronicled at length in Runyon, that

Congress has considered and rejected legislation “that would have

repealed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 ... insofar as it affords private

sector employees a right of action based on racial discrimina

tion in employment.” Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. at 174 and

n.ll. The Court was moved by the Senate’s rejection of the pro

posal to observe that [tjhere can hardly be a clearer indication

of congressional agreement with the view that § 1981 does reach

private acts of racial discrimination.” Id. (emphasis in original).

Similar ratifications have occurred with other civil rights

legislation in subsequent years. In considering legislation to

amend the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974, 15 U.S.C. §

1691, to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race and other

grounds in the granting of credit, the House heard testimony that

$ 1981 already accorded protection against racial refusals to ex

tend credit.” Although specifically advised that § 1981 reaches * I

11 As explained by the Court, Senator Williams, the floor manager of the bill

that was enacted as the E(|ual Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, describ

ed Senator Hruskas’ amendment to make Title VII and the Equal Pay Act the

exclusive federal sources of relief for employment discrimination as an effort

to " strip from (the) individual his rights that have been established going back

to the first Civil Mights Act of 1866.' " Id., quoting 118 Cong. Rec. 3371 3372

(1972).

'* In hearings on the bill Irefore the Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs of the

I louse Committee on Ranking, Currency and Money, Arthur S. Flemming,

Chairman of the United States Civil Rights Commission, testified:

Minority groups citizens theoretically would seem to be afforded

protection against credit discrimination by the Civil Rights Act of

(footnote continued)

14

private discriminatory refusals to contract,15 when the amend

ments to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act were enacted in 1976,

Congress chose not to repeal or modify the judicial construction

this and other courts had given § 1981.'"

In 1976, after Runyon, Congress again endorsed this Court’s

construction of § 1981 when it enacted the Civil Rights Attorney’s

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988. In explaining the pur

pose of the amendment as giving the federal courts discretion

to award attorneys’ fees in suits brought to enforce the civil rights

acts which Congress has passed since 1866, Congress specifical

ly observed that the Act of 1866 covered the same ground as later

1866 which forbids discrimination in contractual traasactioas and

declares that all citizens have equal rights to “ inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal pn>[)erty.” Experience

of more than a century however, amply demonstrates that the broad

protections of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 are insufficient to effec

tively guarantee minority citizens equal credit opportunities.

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs of the Committee on

Hanking, Currency and Money, House of Representatives, 94th Congress, 1st

Sess., on H.R. 3386, p. 41 (C.P.O. 1975). In addition. Dr. Flemming testified

that the prohibitions proposed in the amendments would overlap with those

contained in section 805 of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. 5 3605,

against racial discrimination in mortgage financing, Id. at p. 46 (“ Unlike Title

VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, H R. 3386 forbids discrimination based

on race ... in all areas of credit, not just mortgage finance.")

“ At the time Chuirman Hemming testified, April, 1975, at least seven circuit

courts of ap|>eals had held that § 1981 reaches private race discrimination, see

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. at 459 n.6, anti Jones o. Alfred

II. Mayer Co., was settled law in this Court.

“ Congress did, however, require [versons aggrieved by housing related credit

discrimination to choose I vet ween the remedies afforded Ivy the credit amend

ments and the Fair Housing Act. See 15 U.S.C. tj 1691e(i):

No |verson aggrieved by a violation of this subchapter ami by a viola

tion of section .3605 of Title 42 shall recover under this sulvchaptcr

anti section 3612 of Title 42, il such violation is lvast*l on the same

transaction.

15

enacted civil rights statutes and, by making attorneys’ fees

available, acted to strengthen its protections.17

Congress time and again has ratified the judicial determina

tion that the 39th Congress intended § 1981 to reach private

discrimination. Cj. Lindahl v. OPM, 470 U.S. 748, 782 n.15 (1985)

(“ Congress is presumed to be aware of [a] ... judicial interpreta

tion of a statute and to adopt that interpretation when it re-enacts

a statute without change ....’ ”). Indeed, it is apparent that Con

gress has relied and built on Jones, Runyon and their progeny

in enacting other statutes. If Congress had any inclination to over

rule Runyon, it has had ample opportunity to do so. Moreover,

it has foregone countless opportunities to pass legislation con

taining protections of the kind tj 1981 is understood to contain

based on its view that (here was no need to enact such a law.

Proper deference to congressional endorsements of judicial in-

terpretations of its acts requires this Court to abstain from

challenging Congress to act once more.

” See s ReP No 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., 4 reprinted at 1976 U.S. Code

Cong. & Admin. News 5908, 5911:

(F)ees are ... suddenly unavailable in the most fundamental civil

rights cases. For instance, fees are now authorized in an employ

ment discrimination suit under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, but not in the same suit brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1981, which

protects similar rights but involves fewer technical prerequisites to

. the filing of an action. Fees are allowed in a housing discrimina

tion suit brought under Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968,

but not in the same suit brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1982, a

Reconstruction Act protecting the same rights.

The Senate Report demonstrates Congress’ determination to make attorneys’

fees available to prevailing plaintiffs in actions under the Civil Rights Act of

1866 to redress private discrimination, and its express approval of the construc

tion (vf that act to reach private conduct. The Report specifies that the Fees

Act would overrule the Court's disapproval of fee awards in cases of private

discrimination cited in Aleyeska Pipeline Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240, 270 n.46 (1975) (disapproving fee awards inter alia in Knight v. Auciello,

45.3 F2d 852 (1st Cir. 1972) and Lee o. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d

14.3 (5th Cir. 1971) which IhiIIi permitted fees in actioas under § 1982 to redress

private housing discrimination). Id., at 5911-12 and n.3.

16

3. Individuals and States Have Relied Upon Section 1981 to

Secure Redress For Invidious Race Discrimination in Its

Myriad Forms.

Suits under § 1981 to redress racial discrimination are now com

monplace; their sheer numbers reflect the centrality of the statute

to our legal fabric. The lower courts have developed a body of

law interpreting § 1981 that enables individuals to obtain

remedies not available under Tide VII. That such a development

would occur was foretold by the Court’s recognition in Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. at 461 that the “ remedies

available under Title VII and under § 1981, although related,

... are separate, distinct and independent.”

While courts fashioning equitable remedies under § 1981 can

require relief similar to that available under Title VII, such as

hiring, promotion, reinstatement, retroactive seniority and af

firmative action,"* * § 1981 covers all employers, not just those with

fifteen or more employees. A § 1981 plaintiff can obtain legal

remedies not available under Title VII. “An individual who

establishes a cause of action under § 1981 is entitled to ... legal

relief, including compeasatory, and under certain circumstances,

punitive damages.” Id., 421 U.S. at 460. Thas, individuals prevail

ing under § 1981, unlike those pursuing Title VII claims, may

recover for the mental distress that results from the racial

discrimination.” Courts may award punitive damages for serious

violatioas of § 1981.2" A backpay award under fj 1981 Ls not limited

"See eg. Davis v. County of Las Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1977), vacated

as moot, 440 U.S. (125 (1979); Campbell v. Gadsden School Oust., .534 F.2d 650

(5th Cir. 1976); Easley v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc., 572 F Supp. 402 (E.D. Mo.

1983), affd in part and revd in part, 758 F.2d 251 (8th Cir. 1985).

• E g , Williams tx Thins World Airlines, 660 F.2d 1267, 1272-73 (8th Cir. 1981);

Gore v. 71 inter, 563 F.2d 159, 164 (5th Cir. 1977).

” E g ., Beaujord v. Sisters of Mercy-Province of Detroit, 816 F.2d 1104, 1108-09

(6th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 108 S. Ct. 259 (1988); Hunter v. Allis-Chalmers

Coift., Engine Div., 797 F2d 1417, 1425 (7th Cir. 1986); Stallworth v. Shuler,

111 F.2d 1431, 1435 (Uth Cir. 1985); Clairbome v. Illinois Cent. B.B., 583 F.2d

143 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 442 U.S. 934 (1979); Allen ix Amalgamated

Transit Union Local 7HH, 5.54 F.2d 876 (8th Cir ), cert, denied, 431 U.S. 891

(1977).

17

to the two year limitation specified for Title VII, id., but rather

is governed by the analogous personal injury limitation period

provided by the law of the state where the action is commenc

ed. Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 107 S. Ct. at 2621.” Moreover

because a § 1981 plaintiff, unlike one pursuing only Title VII

relief, may be entitled to legal relief, he can demand a jury trial.”

The statute has been employed to redress racial discrimina

tion relating to contracts in numerous contexts other than employ

ment. Runyon approved its applicability to private schools and

it has since been employed by those seeking to redress discrimina

tion in education.” Individuals have invoked it to vindicate the

right to non-discriminatory access to restaurants,” clubs,” and

recreational facilities” where the other applicable federal law

does not provide for monetary damages. See 42 U.S.C. §

2000a- 3 . It has been utilized to challenge racial denials of

’ ,,owever- there individuals who have foregone Title VII actions which

U S C T o ! inr C,T ,0, V 300- ^ admin*‘ ra“ ve filing period,’ see 42

is o v e r r l l^ C ’ °" * ‘° d '° federal relief is lost if Runy°n

" EdUT LZ f , ? " * VerU>1' 717 F2d 761 763 <3d Cir vacated on other

gmunris, 468 U.S. 1201 (1984); Setser v. Novack Inv. Co., 638 F.2d 1137 (8th

S h c T i iS ! ’ 454 us 1064 (1981); Moore u- Sun C)il Co■ 636 F2d 154

” SZ U y iW M Sch Jor G,rfe’ 541 F2d 1124 (5th Cir. 1976); Phelps

ix Washburn University of Topeka, 632 F. Supp. 4.55 (D. Kansas 1986).

See Wyatt v. Security Inn Eood b Beverage, Inc., 819 F.2d 69 (4th Cir 1987)

r ^ " ^ T d* ot m'£m ,n ’— ** *"-*■ * *1

r ........ * * c“ ' « »

" See ()l* man v- hake Hills Swim Club, Inc., 495 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1974).

Scotttx Young, 421 F.2d 143 (4th Cir), cert, denied, 398 U.S. 929 (1970)- Durham

v. lied Lake Pishing b Hunting Club, 666 F. Supp. 9.54 (WD Tex 1987)

18

housing opportunities,” utility services,” and access to roads.”

Others have sought remedies for racial discrimination in access

to insurance coverage” and medical treatment.5' And it has been

used by those seeking relief from racial discrimination in com

mercial ventures,52 franchise relationships,55 and banking

transactions.”

States, like individuals, have invoked § 1981 to redress private

racial discrimination. In fact, one of the cases under $ 1981 to

reach this Court, General Building Contractors Assn. o. Pa., was

an effort by a state, acting as parens patriae, to seek redress for

racial discrimination in private employment. Likewise, New York

frequently has proceeded under <) 1981 as parens patriae for relief *

17 See Movable v. It. Walker 0 Associates, 644 F.2d 390 (5th Cir. 1981); Quinones

v. Nescie, 111) F.R.D. 346 (E.D.N.Y. 1986); Jiminez v. Southridge Co-op, Sec-,

lion I, 626 F. Supp 732 (E.D.N.Y. 1985); Bendetson o. Patjson, 534 F. Supp 539

(D. Mass. 1982). But see Spann v. Colonial Village Inc., 662 F. Supp. 541, 547

(D. DC. 1987) (§ 1981 not available to redress racially discriminatory real estate

advertising); Saunders v. General Services Corf)., 659 F. Supp. 1042, 1062-63

(E.D. Va. 1986) (same).

“ See Cody i>. Union Electric, 518 F.2d 978 (8th Cir. 1975).

* Compare Jennings v. I’atterson, 488 F.2d 436 (5th Cir. 1974) with Memphis

v. Greene, 451 U S. 100 (1981).

" See Sims v. Order of United Commercial Drivelers of America, 343 F. Supp.

112 (D. Mass 1972). But see Mackey v. Nationwide Ins. Companies, 724 F.2d

419 (4th Cir. 1984).

u llall v. Bio-Medical Application, Inc., 671 F.2d 300 (8th Cir. 1982); Taylor

v. Flint Osteopathic Hasp. Inc., 561 F. Supp. 1152 (E.D. Mich. 198;!).

" See Fraser v. Doubleday O Co. Inc., 587 F. Supp. 1284 (S.D.N.Y. 1984); Viet

namese, Etc. i>. K nights of K.K.K., 518 F. Supp. 993 (S.D. Tex. 1981); Howard

Sec. Serv. v. Johns Hopkins Hospital, 516 F. Supp. 508, 513 (D. Md. 1981).

11 See Quarles v. CMC (Motor Holding Div), 758 F.2d 839 (2d Cir. 1985); Sud

v. Import Motors Limited, Inc., 379 F. Supp. I0(>4 (W.D. Mich. 1974).

14 See llall v. Pennsylvania State Police, 570 F.2d 86, 92 (3d Cir. 1978).

19

from a pattern and practice of private housing discrimination.55

In addition, both Massachusetts and California provide civil

causes of action under state statute” for conduct violating § 1981

and have sued under the statutes to redress acts of racial harass

ment. The applicability of § 1981 to private conduct has

strengthened state anti-discrimination efforts.57

State courts have widely received § 1981 as a means for redress

ing racial discrimination in private contracts.” Recently, in Smith

v. United Technologies, Essex Group, 731 P.2d 871 (Kan. 1987),

the Kansas Supreme Court affirmed a jury award of $55,000 in

compensatory and punitive damages to a black employee who

sued under § 1981 for his discharge from employment in retalia

tion for having filed a discrimination charge with the Kansas

Commission on Civil Rights. In Brant Const. Co. v. Lumen

Const. Co., 515 N.E.2d 868 (Ind. App. 3 Dist. 1987). the court

affirmed a determination under § 1981 that a prime contractor,

because of race, had interfered with and rendered insolvent a

subeontractors business by wrongfully exercising control over the

See e g., People of the State of New York v. Merlino, 88 Civ. 3133 (S D N Y )•

People of the State of New York v. LaRosa Realty, Inc., Civ. Action No’

CV-85-4459 (E.D.N.Y.) (Judgment for $15,000 in damages for racial steering);

People of the State of New York v. Mahler Realty, Civ. Action Na CV-85-4460

(Judgment for $14,000 for racial steering); People of the State of New York v

Data-Butterfield Inc., Civ Action Na 80-365 (E.D.N.Y.) (judgment for $142,000

for racial steering).

" See Mavi Cen Law5 Ann Ch. 12 §§ UH, 111, 11J; Cal Civil Code § 52 1

(West 1988).

17 In addition, guided in part by Runyons teaching that discrimination in private

contracts is proscril>ed hy § 1981, states have initiated race-conscious set-aside

programs to create opjiortunities for minority business enterprises. See e g., N.Y.

Exec. Order 21 (1983); N.Y. Pub. Auth. Law § 1766-c 14(a)(i) (McKinney 1986)-