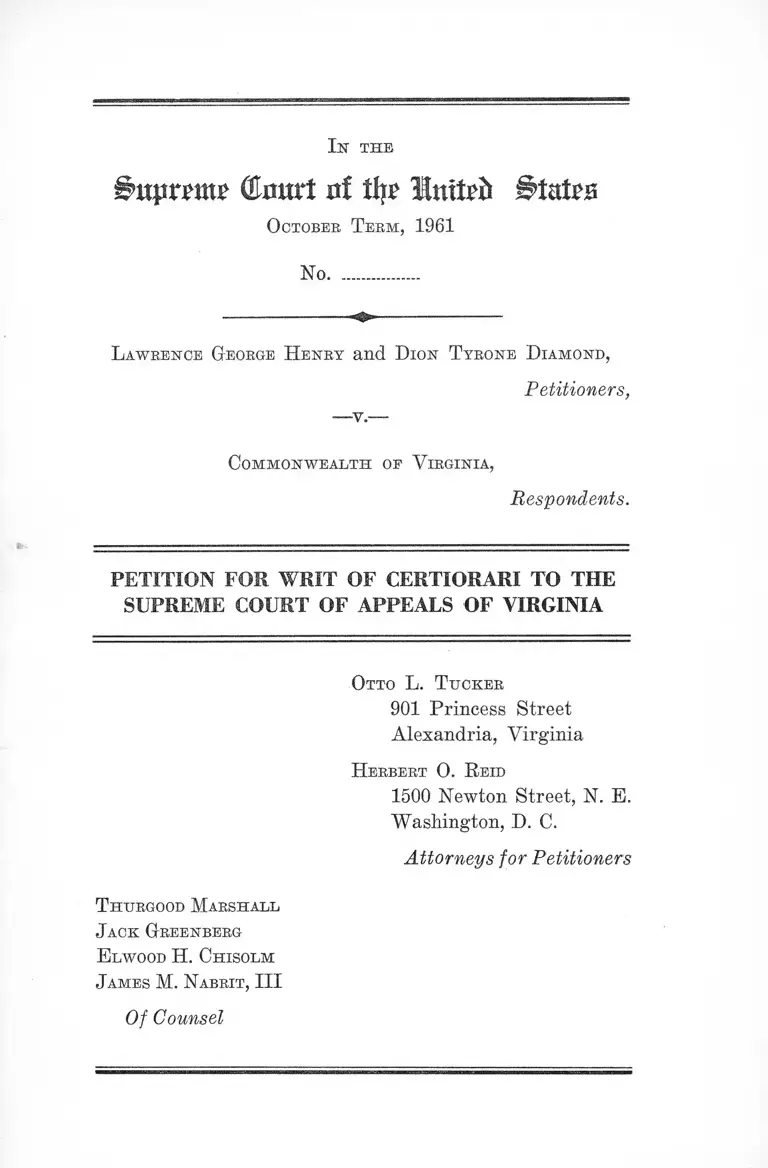

Henry v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Public Court Documents

April 25, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, 1961. fe51abff-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77a40623-b931-43a9-941f-1a8fd7c22d29/henry-v-virginia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-appeals-of-virginia. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

Supreme dmtrt nf % Itutefc States

October T eem, 1961

No................

L awrence George H enry and Dion T yrone Diamond.

-v .—

Petitioners,

Commonwealth op V irginia,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

H erbert 0 . R eid

1500 Newton Street, N. E.

Washington, D. C.

Attorneys for Petitioners

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

E lwood H. Chisolm

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below........ .................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........................ 1

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved...... 3

Statement ............................................................. 3

How the Federal Questions VvTere Raised and Decided .. 5

Reasons for Granting the W rit.................................... 9

I. The public importance of the issues presented...... 9

II. Constitutional questions resolved by the Court be

low in conflict with or in advance of this Court’s

decisions ...................................................-........-..... 12

A. The decision below affirming a criminal con

viction procured by interpreting and ap

plying the state’s “Trespass after Warning”

statute as eliminating any requirement of

“scienter” or “mens rea” conflicts with deci

sions of this Court and resolves important

constitutional questions not yet determined

by this Court ..................................................

B. The decision below affirming these convic

tions is in conflict with prior decisions of

this Court prohibiting racially discrimina

tory state action ...........................................

12

21

11

C. The decision below affirming these convic

tions is in conflict with or in advance of this

Court’s decisions prohibiting unwarranted

state interference with the exercise of rights

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment .... 25

Conclusion .................................................................... 31

Appendix ................................................................. la

Table of Cases

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 ...................... .......... 12

Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165 U. S. 578, 17 S. Ct. 427,

41 L. ed. 832 ................................................................ 29

Avent v. North Carolina, Pet. for cert, filed, 29 U. S. L.

Week 3336 (No. 943, 1960 Term, renumbered No. 85,

1961 Term) ................................................................. 11

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ................................ 23

Bates v. Little Bock, 361 U. S. 516 ..... ...................... 28

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 IT. S. 497 .................................- 29

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) ................................................................. - 12

Briggs v. State, Ark. Sup. Ct. (No. 4992) ..... ................ 11

Briscoe v. Louisiana, cert, granted Id. (No. 618, 1960

Term, renumbered No. 27, 1961 Term) ..................... 11

Briscoe v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 432 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) .............................. ............................................- 11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60 .................................. 22

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 IT. S. 495 ................................... 27

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S. 715 23

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 IT. S. 296 .........................20, 26

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S. 568 .............. 26

PAGE

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ....................................... 23

Cole v. Arkansas, 339 U. S. 196....................................... 16

Commonwealth v. Richardson, 313 Mass. 632 .......... . 20

Connally v. General Const. Co., 269 U. S. 385 .............. 19

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 ..... ................................. 13, 23

Crossley v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 339 (Tex. Crim. App.

1961) ........... ...... ............... .......................................... 11

Cunningham v. Beagle, 135 IT. S. 1 (1890) ................. 25

Davis v. Balson, 133 U. S. 333 ....................................... 26

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353 ......... .......... ...... ......... 26

Drews v. State, 167 A. 2d 341 (Md. 1961), jurisdictional

statement filed 29 U. S. L. Week 3286 (No. 840, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 71, 1961 Term) ..................... 11

DuBose v. City of Montgomery, 217 So. 2d 845 (Ala.

App. 1961) ....- ...... .......... .................... .............. ......... 11

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 IT. S. 202 ............... ..................... 22

First National Bank of Guthrie Center v. Anderson,

269 U. S. 341................................................................ 13

Fox v. North Carolina, Pet. for cert, filed, Id. (No. 944,

1960 Term; renumbered No. 86, 1961 Term) .............. 11

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man.

2334 (Wash. Super. Ct. 1959) ................................... 28

Garner v. Louisiana, cert, granted 29 U. S. L. Week

3276 (No. 617, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 26, 1961

Term) ...................... .......... ........................................ 11

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, aff’g 142 F. Supp. 707

(M. D. Ala. 1956) ... ............ .................................. ..... . 22

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ......................... . 21

Griffin v. Md., Pet. for cert, filed Aug. 4, 1961, 287

(Oct. Term 1961) decided June 8, 1961 (Md. Ct. App.

No. 248, Sept. 1960 Term) .......................................... 11

Ill

PAGE

1Y

Griffin v. State, 351 U. S. 12.................................... ...... 16

Hall v. Commonwealth, 188 Va. 72 ............................ 13,19

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 .................. ................. 20

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ..................... 22

Hoston v. Louisiana, cert, granted, Id. (No. 619, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 28, 1961 Term) ..................... 11

Johnson v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) ............ ..................................... ....... ..... ............ 11

Jones v. Opelika, 319 U. S. 103............................. ......... 26

Jordan v. DeGeorge, 341 U. S. 223 ............................ . 20

King v. City of Montgomery, 128 So. 2d 340 (Ala. App.

1961) ................... ............................... ........................ 11

King v. State, 119 S. E. 2d 77 (Ga. 1961) ................... . 11

Kotch v. Board of River Port Pilot Com’rs., 330 U. S.

552, 67 S. Ct. 910, L. ed. 1093 ....................................... 24

Lambert v. California, 355 U. S. 225 ............................ 15

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ......................... 19

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501............................ 14, 25, 27

Martin v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 233 (Ga. App. 1961) ___ 11

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141................................13, 27

Morisette v. U. S., 342 U. S. 246 ................................... 15

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113 ....................................... 28

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105......................... 26

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .....................27, 28

National Labor Relations Board v. Babcock and Wilcox

Co., 351 H. S. 105........................................ ................. 28

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ................................... 26

PAGE

V

Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454 ............................ 26

People y. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d 277 (1948) 28

Ealey v. Ohio, 360 U. S. 423 .......................................12,19

Eandolpli v. Commonwealth, Pet. for cert., filed 30 U. S.

L. Week, 3040 (No. 248, Oct. Term 1961) ................. 3,11

Bepublic Aviation Corp. v. National Labor Relations

Board, 324 U. S. 793, note 6 ....................................... 28

Rucker v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) .......................................................... - ............... 11

Rucker v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 325 (Tex. Crim. App.

1961) ........................................................................... 11

Samuels v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 231 (Ga. App. 1961) ...... 11

Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344 ........................ ............. - 20

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................. - 23

Slagle v. Ohio, 366 IT. S. 259 „....................................... 12

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 ... ................................ 15

State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533,

aff’g 168 F. Supp. 149 (E. D. La. 1958) ..................... 22

State ex rel. Steele v. Stoutamire, 119 So. 2d 792 (Fla.

1960) ................... ............................................ - ......... 11

Steele v. City of Tallahassee, 120 So. 2d 619 (Fla. 1960) 11

Steele v. City of Tallahassee, cert. den. 29 U. S. L. Week

3263 (No. 671, 1960 Term) ........................ ................ 11

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 .......... .............. 27

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ................................ 27

Tucker v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 433 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) ......... ................................................................. 11

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery, 255 U. S. 81 .......... 19

United Steelworkers v. National Labor Relations

Board, 243 F. 2d 593 ................................................ - 28

PAGE

VI

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 ..... ........ .......................... 29

Walker v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 284 (Ga. App. 1961) ...... 11

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178......................... 20

Watson v. Jones, 13 WAll. 679 ....................................... 26

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183............................ 20

Williams v. North Carolina, Pet. for cert, filed 29

U. S. L. Week 3319 (No. 915, 1960 Term; renum

bered No. 82, 1961 Term) ..................... ................... 11

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .........................19, 20

Wise v. Commonwealth, 98 Va. 837 ............................ 17,18

Yiek Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ............................ 22, 25

PAGE

Other Authorities:

A Bibliography of the Student Movement Protesting

Segregation and Discrimination, Tuskegee Institute,

Alabama, 1960 ........................................................... 10

Dime Store Demonstration Events and Legal Problems

of the First Sixty Days, 1960, Duke Law Journal 315

(1960) .......................................................................... 10

Hall, Jerome, General Principles of Criminal Law (2nd

Ed.) 1960, pp. 70-71 .............. 15

Lunch Counter Demonstrations: State Action and the

Fourteenth Amendment, 47 Va. L. Rev. 105................ 10

Mueller, On Common Law Mens Rea, 42 Minn. L. Rev.

1043 ............................................................................. 15

Newsweek, August 7, 1961, p. 26 ................................. 10

New York Times, October 18, 1960, p. 47, col. 5 (late

city edition) ............................................................... 10

vn

New York Times, July 30, 1961..................................... 10

New York Times, August 13, 1961, pp. 56 and 4 2 ...... 10

Perkins, Prof. M., Criminal Law (1957) pp. 681-683 ..15,19

Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Col. L. Rev. 55

(1933) ......................................................................... 16

Washington Post, July 1, 1960 and August 21, 1960 .... 9

Statutes:

Dallas, Texas 1960 Ordinance (6 Race Rel. L. Rep. 317) 12

Louisiana Acts, 1960, Nos. 70, 77, 80 ............................ 12

Six Race Relations Law Reporter, No. 1, p. 2 .......... 10

South Carolina Acts, 1960 No. 743 .............................. 12

Title 28 U. S. C. 1257(3) .............................................. 2

Virginia Acts, 1960, ch. 97.............................................. 12

Virginia Code 1950 [1960 Amendment] Sec. 18.1-172 .... 17

Virginia Code 1950 [1960 Amendment] See. 18.1-173

3,4,13,17

PAGE

I n the

§>npvmt tour! of % Ittitpib States

October T erm, 1961

No................

L awrence George H enry and Dion Tyrone Diamond,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Commonwealth oe Virginia,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

entered April 25, 1961, in the above-entitled cause.

Opinion Below

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia issued the

orders complained of without opinion. The orders are ap

pended hereto, infra at pages la, 2a.

Jurisdiction

The judgments sought to be reviewed are those of the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, dated April 25,

1961, refusing petitions for writs of error and supersedeas

to review judgments rendered against petitioners by the

2

Circuit Court of Arlington County, Virginia, on November

3, 1960, in a prosecution for criminal trespass (infra pages

la, 2a). The effect of the denial of the petitions for writs

of error and supersedeas is to affirm said judgments.

On July 19, 1961, the time for filing a petition for writ

of certiorari was extended by Mr. Justice Clark to and

including August 23, 1961.

The jurisdiction of this Court to review the judgment

below rests on Title 28 U. S. C. § 1257(3).

Q uestions P resen ted

1. Whether the State criminal trespass statute inter

preted and applied in the instant case so as to eliminate

any requirement of scienter or mens rea is violative of

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

2. Whether the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment permit the state to use its

executive and judiciary to enforce the racially discrimina

tory practices of a business which has opened its property

to the general public by invoking the state criminal trespass

statute to enforce such racial discrimination within the

same property.

3. Whether the convictions obtained below infringe

rights of expression and of association and the right to

contract and to secure property, and to otherwise enjoy the

liberties of free men, which are guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment.

3

S tatu to ry and C onstitu tional P rov isions Involved

1. These cases involve § 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

2. These cases also involve the following provision of

the Code of Virginia (1950, as amended 1960):

§ 18.1-173. Trespass after having been forbidden to

do so.—If any persons shall without authority of law

go upon or remain upon the lands, buildings or prem

ises of another, or any part, portion or area thereof,

after having been forbidden to do so, either orally or

in writing, by the owner, lessee, custodian or other

person lawfully in charge thereof, or after having

been forbidden to do so by a sign or signs posted on

such lands, buildings, premises or part, portion or area

thereof at a place or places where it or they may be

reasonably seen, he shall be deemed guilty of a misde

meanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished

by a fine of not more than one thousand dollars or by

confinement in jail not exceeding twelve months, or

by both such fine and imprisonment. (Portions itali

cized added by 1960 amendment.)

Statem ent

These cases like the “Richmond Student Protest Cases”

filed in this Court on July 22, 1961, Randolph v. Common

wealth of Virginia, 30 U. S. Law Week 3040 (No. 248, Oct.

Term 1961), involve the issue of whether the Virginia tres

pass statute may be used to convict Negroes previously

admitted to a restaurant, and permitted to purchase ar

ticles to take out, but refused food service at a counter

solely because of their race, for failure to leave the prem

ises when told to do so.

4

On the 10th day of June, 1960, petitioners went into How

ard Johnson’s Restaurant in Arlington County where they

purchased and requested receipts for popcorn, chewing

gum and candy from an assistant manager at a counter

where these items were displayed and the cash register

was located (Tr. 6). One of the petitioners sat down at the

counter and was asked to leave by the manager (Tr. 3, 19).

A police officer, who was sitting at the other end of the

counter, was asked by the manager to take petitioners out

(Tr. 4, 11). The manager had requested the petitioners

to leave and asked for the aid of the police because he

believed that there was a law prohibiting the restaurant

from serving colored people (Tr. 15). Petitioners were

well-mannered and conducted themselves properly (Tr. 13,

15, 20); they were asked to leave solely because of race

(Tr. 17). They refused to do so and were arrested (Tr. 19).

The warrants of arrest, obtained and sworn to by Lieu

tenant E. A. Summers and Officer Donald W. Pelassaro

of the Arlington County Police Department, charged peti

tioners for failing to leave the premises of Howard John

son’s Restaurant, 4700 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia,

after having been requested to do so by the person lawfully

in charge thereof, in violation of Title 18.1-173, Virginia

Code 1950 (1960 Amendment) (R. 1, 2).

Petitioners’ cases were consolidated and tried together

on October 31, 1960, before a jury in the Circuit Court of

Arlington County (Tr. 1). Various federal constitutional

defenses were made throughout (R. 17, 18, 19, 20) and at

the close of (R. 18, 20) the trial, but were overruled. The

jury found both petitioners guilty as charged and fixed

punishment at $25.00 fines (R. 18, 20).

On application to the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia, that Court, by a judgment or order, dated April

25, 1961, denied their petitions for writs of error and

5

supersedeas and thus affirmed the judgment of convictions

below (Appendix, infra, la, 2a).

How th e F edera l Q uestions W ere R aised an d D ecided

At the conclusion of the evidence for the Commonwealth,

the petitioners “moved the Court to strike the evidence of

the Commonwealth of Virginia, which said motion the

Court denied and to which said ruling of the Court the

(petitioners) excepted” (R. 17, 19). The reasons assigned

by the petitioners were as follows:

First, that, if this statute does not require proof of

“scienter” or “mens rea,” the statute is unconstitutional;

and, on the other hand, if the statute does require “scienter”

or “mens rea,” the Commonwealth failed to produce evi

dence that petitioners did not have a bona fide belief or

claim of right and; therefore, that any conviction obtained

without proof of this element would be violative of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Tr. 25-26).

The second reason assigned by the petitioners in support

of their motion to strike was that application and enforce

ment of Virginia’s criminal trespass statute was use of the

state’s criminal process in a manner which fostered, imple

mented and enforced discrimination and exclusion on the

basis of race in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The instant owner in pursuing a policy of denying service

to all Negroes was not exercising any individual choice

which he may or may not have to select or reject particu

lar customers, but on the contrary the owner in the first

instance was engaging in a racial classification as to an

identified group because he believed compelled by law,

custom, or fear of economic reprisals by other potential

customers. When the owner sought and received the aid

of the state to effectuate this policy and practice of racial

6

classification, discrimination and exclusion, such state ac

tion violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

The remaining reason assigned in support of petitioners’

motion to strike was that application and enforcement of

the criminal trespass statute under circumstances here

where petitioners had entered the premises, made certain

purchases, amounted to unwarranted state interference

with the exercise of their constitutional rights protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Following argument by the Commonwealth’s attorney in

opposition thereto (Tr. 28-31), the court rendered an oral

opinion which specifically treated and overruled each of

these contentions (Tr. 31-34).

Subsequently, at the close of petitioners’ case and during

argument with respect to proposed instructions, their mo

tion to strike the Commonwealth’s evidence was renewed

on the grounds previously assigned and again it was denied

(Tr. 56). Moreover, over petitioners’ objections, the court

accepted Instruction 2 of the Commonwealth and refused

Instruction E of petitioners (Tr. 55, 56)—the former ex

cluding and the latter including the element of “mens rea”

or “scienter” (see R. 7, 14; Tr. 57). At this juncture the

court said (Tr. 56):

“Well, I don’t know whether it comes too late or not,

but it is going to be refused. I have not changed my

mind about it. I said that the gist of it lies in In

struction E that was refused, and Instruction 2 that

was granted. I can see that is a really important ques

tion.

As I indicated before, I do not find any cases which

support the defendant’s theory. The closest I can come

to is the Barrows versus Jackson, and I do not think it

goes this far, and I am not willing to go this far, unless

7

the Supreme Court says we have to go this far. I do

not think the Supreme Court says that we have to

go this far.

We have a conflict here of rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment, and we have a conflict of property rights.”

Again, after submission of the case to the jury, the court

denied petitioners’ federal contentions when the jury re

turned to the courtroom for further instructions, viz. (Tr.

61-62):

Jury Foreman: Your Honor, some of the jurymen

have a question or two that probably if we understood

might help us get to a fairly quick resolution of the

problem. There are two questions.

The Court: Proceed.

Jury Foreman: The first one is, as used in Instruc

tion 2, what does “authority of law” mean?

The Court: It means some writ of Court or some

writ of tenancy or some legal right of that sort, some

right of entry.

Jury Foreman: Right of entry?

The Court: Some legal writ of entry or some right

of a tenant, some person who has the right of the

property.

Jury Foreman: The second question is: Does

“trespassing” mean that a person can be asked to leave

a restaurant such as Howard Johnson’s, serving the

public, without cause?

The Court: Yes, sir.

Jury Foreman: Thank you.

To such further instructions, petitioners objected and noted

an exception (Tr. 62).

8

After the verdict was rendered and the jury discharged,

petitioners moved to set aside the verdict of the jury

as contrary to the law and the evidence and without evi

dence to support it (Tr. 63). In disposing of this matter

adversely to the petitioners, the court observed (Tr. 63):

On the evidence, I don’t think it is contrary to the

evidence. It seems to me it would be futile to argue

that.

I think there are two legal questions here, but it

seems to me it has already been argued. One of them

is the question the jury just asked. The other one,

which is closely analogous to the covenant case and

how far the Court is going to go in that direction, on

the grounds stated, is contrary to the law and evidence.

The Court further stated (Tr. 66) :

I consider two sections here. I do not consider that

one too seriously, the one about how far they are going

to go in this thing which the Supreme Court says is

a right, but you cannot enforce it in a Court, as they

said in the restriction or covenant case, how far they

are going to go. They haven’t gone quite this far yet,

and I do not know that they ever will. Maybe they

will. Maybe they will do it just like you asked them to.

But certainly you do not have any case that says that

they will go that far. The farthest I have seen them

go is Barrows against Jackson.

The second is the question the jury asked me, and you

do not have any case citing that.

So if you want some new law made, you will have to

get it made somewhere else.

The motion is denied.

The Notice of Appeal and Assignments of Error prop

erly preserved the various federal constitutional questions

9

raised in the trial court (R. 26). The petition for writ of

error and supersedeas to the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia properly presented the same for decision. The

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia disposed of these

questions by a judgment or order summarily refusing said

writ of error and supersedeas (R. 69, 70).

R easons fo r G ran ting th e W rit

These cases involve substantial questions affecting con

stitutional rights of great public importance resolved by

the court below in conflict with principles expressed by

this Court or in advance of determination by this Court.

I.

T he pub lic im portance o f th e issues p resen ted .

The instant cases arise out of the proliferating “sit-in”

demonstrations and raise federal questions of great public

importance undecided by this Court. These petitioners

were two of the student leaders who led the successful

“sit-in” demonstrations against the denial of equal treat

ment in public places of accommodation in that part of the

greater Washington Metropolitan area located in Virginia

and Maryland. Even though their activity, in conjunction

with others, achieved a substantial change in the racial

discriminatory policies and practices in the area,1 these

petitioners were involved in many arrests and convictions

in Maryland and in the instant cases in Virginia.

Although the “sit-in” demonstrations against discrimina

tion in, and exclusion from, public places of accommoda

tions “received widespread approval, many demonstrations

1 Washington Post, July 1, 1960 and August 21, 1960.

10

resulted in arrests of persons involved, and, since many of

the convictions have been appealed, serious constitutional

questions have been raised.” 2 These demonstrations, be

ginning in February, 1960, spread quickly throughout the

South and into other sections of the Country,3 and involved,

during the past year, thousands of students nationally in

activity similar to that for which the petitioners have been

convicted.4

In a large number of places, this nationwide protest has

prompted startling changes in the practices of racial dis

crimination and exclusion in places of public accommodation

with the result that service is now afforded in many addi

tional areas on a non-segregated basis. The number of

cities, prompted by these demonstrations, opening facili

ties on a non-segregated basis was at one time reported as

112, New York Times, October 18, 1960, page 47, col. 5

(late city edition). However, this figure is daily increasing

with announcements like those from Atlanta, New York

Times, July 30, 1961 and August 13, 1961, pages 56 and 42

respectively, and Dallas, Newsweek, August 7, 1961, page

26.

Despite widespread gains in non-discriminatory treat

ment at places of public accommodation which enhanced the

Country’s prestige internationally, most of these demon

strations, as in the case at bar, have culminated in arrests

and criminal prosecutions which variously present as un

derlying questions the issues presented herein. Many of

these cases have already reached the appellate courts of

2 Lunch Counter Demonstrations: State Action and the Four

teenth Amendment, 47 Va. L. Eev. 105. For a concise treatment of

the history and magnitude of these demonstrations see ibid.; see

also Pollitt, Dime Store Demonstration Events and Legal Problems

of the First Sixty Days, 1960, Duke Law Journal 315 (1960).

3 6 Race Relations Law Reporter, No. 1, p. 2.

4 A Bibliography of the Student Movement Protesting Segrega

tion and Discrimination, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, 1960.

11

Louisiana,5 North Carolina,6 Florida,7 Maryland,8 Arkan

sas,9 Alabama,10 Georgia,11 South Carolina,12 Texas,13 and

Virginia;14 countless others are at the trial level in those

states and, additionally, in Kentucky, Tennessee, West

Virginia and Mississippi.

5 E.g., Gamer v. Louisiana, cert, granted 29 U. S. L. Week 3276

(No. 617, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 26, 1961 Term) ; Briscoe v.

Louisiana, cert, granted, Id. (No. 618, 1960 Term; renumbered No.

27, 1961 Term); Boston v. Louisiana, cert, granted, Id. (No. 619,

1960 Term; renumbered No. 28, 1961 Term).

6 E.g., Avent v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, 29 U. S. L.

Week 3336 (No. 943; 1960 Term; renumbered No. 85, 1961 Term);

Fox v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, Id. (No. 944, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 86, 1961 Term); Williams v. North Caro

lina, petition for cert, filed 29 U. S. L. Week 3319 (No. 915, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 82, 1961 Term).

7 E.g., Steele v. City of Tallahassee, cert, denied 29 U. S. L. Week

3263 (No. 671, 1960 Term); Steele v. City of Tallahassee, 120 So.

2d 619 (Fla. 1960); State ex rel. Steele v. Stoutamire, 119 So. 2d

792 (Fla. 1960).

8 E.g., Griffin v. Maryland, petition for cert, filed Aug. 4, 30 U. S.

L. Week 3058 (No. 287, 1961 Term) ; Drews v. State, 167 A. 2d 341

(Md. 1961), jurisdictional statement filed 29 U. S. L. Week 3286

(No. 840, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 71, 1961 Term).

9 E.g., Briggs v. State, Ark. Sup. Ct. (No. 4992) with which

Smith v. State (No. 4994) and Lupper v. State (No. 4997) have

been consolidated.

10 E.g., DuBose v. City of Montgomery, 127 So. 2d 845 (Ala. App.

1961); cf. King v. City of Montgomery, 128 So. 2d 340 (Ala. App.

1961).

“ E.g., Samuels v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 231 (Ga. App. 1961);

Martin v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 233 (Ga. App. 1961) ; Walker v. State,

118 S. E. 2d 284 (Ga. App. 1961); cf. King v. State, 119 S. E 2d

77 (Ga. App. 1961).

12 E.g., see Petition for Cert., p. 27 note 15, Briscoe v. Louisiana,

supra, note 5.

13 E.g., Crossley v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 339 (Tex. Grim. App.

1961); Rucker v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 325 (Tex. Grim. App. 1961) •

Briscoe v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 432 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960) ; Tucker

v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 433 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960) ; Johnson

v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960); Rucker v. State,

341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960).

14 Randolph v. Commonwealth, petition for cert, filed 30 U S L

Week 3040 (No. 248, Oct. Term 1961).

12

Beyond the multiplicity of litigation which has resulted

from these student demonstrations, they have created new

problems for local law enforcement authorities15 and they

have spurred the enactment of new laws or more stringent

amendments to existing laws,16 as in the instant case.

It is therefore of great public importance that this Court

consider the issues presented herein so that the courts

below, and people everywhere, can be authoritatively ap

prised regarding the constitutional limitations on state

prosecutions of young people for engaging in this type of

activity in order to secure that equality enjoyed by other

free people. Slagle v. Ohio, 366 U. S. 259; Raley v. Ohio,

360 U. S. 423.

II.

C onstitu tional questions reso lved by th e C ourt below

in conflict w ith o r in advance o f th is C ourt’s decisions.

A. The decision below affirming a criminal convic

tion procured by interpreting and applying the

state’s “Trespass after Warning” statute as elimi

nating any requirement of “ scienter” or “mens

rea” conflicts with decisions of this Court and re

solves important constitutional questions not yet

determined by this Court.

While the interpretation of state legislation is primarily

the function of state authorities, judicial and administra

tive, the construction given a state statute by the state

courts is only binding upon the federal courts as to the

meaning of the construed provisions. Albertson v. Millard,

16 Cf. Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir.

1960).

16 E.g., see Va. Acts, 1960, eh. 97; see S. C. Acts, 1960, No. 743;

La Acts, 1960, Nos. 70, 77, 80; Dallas, Tex., 1960 Ordinance (6 Race

Eel. L. Rep. 317).

13

345 U. S. 242. The supremacy of the Constitution, as well

as this Court’s ultimate authority in the exposition of the

law of the Constitution, is clearly established. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. This Court has announced as its duty

ultimately to pass on the substantive sufficiency of a claim

of federal right. First National Bank of Guthrie Center

v. Anderson, 269 U. S. 341.

Preliminary to the completion of the Commonwealth’s

case, petitioners did not make any motions attacking the

validity of Title 18.1-173 of the Virginia Code or the in

dictment thereunder, relying upon the authority of Hall v.

Commonwealth, 188 Va. 72, and Martin v. Struthers, 319

U. S. 141. In Hall v. Commonwealth, supra, the Virginia

Court of Appeals, while passing upon the validity of this

section (prior to the 1960 amendment), concluded that there

was nothing in this section, when properly applied, which

infringed upon the guarantees of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.17

Upon the completion of the Commonwealth’s case, peti

tioners, thereafter, and at every available procedural op

portunity, sought to assert that their federal rights were

being violated by an interpretation and application of this

section of the Code which eliminated any requirement of

“scienter” or “mens rea” for a conviction (supra, pp. 5-9).

That this precise issue was clearly drawn is indicated by

argument of counsel for petitioners and the Commonwealth,

by the jury’s request for further instruction, and by the

various adverse rulings of the trial court, to which proper

exceptions were taken. The trial court’s position in this

matter, which now stands affirmed by the Supreme Court

17 See Martin v. Struthers, supra. The reference by this Court in

notes 10 and 11 of the Martin case, supra, 147, to the Virginia

“Trespass After Warning” statute, as well as to similar statutes in

other states, is no authority for the instant interpretation and appli

cation.

14

of Appeals of Virginia, was that a violation of this section

occurred when the owner, or person in charge, requested

another to withdraw from the premises and such other

failed to comply. The sum of the trial court’s rulings was

that a conviction was proper where the evidence merely

established a request by the owner, or person in charge, to

withdraw from the premises, given to anyone upon the

premises without authority of law. The court instructed

the jury that the meaning of the phrase “authority of law”

contained in the statute meant “some legal writ of entry

or some right of a tenant, some person who had the right

of the property” (Tr. 61-62). The court further instructed

the jury that a person could be requested “to leave a res

taurant such as Howard Johnson’s, serving the public, with

out cause” and that evidence of such refusal, without more,

was sufficient to sustain a conviction.

The decision below affirming the conviction is an adverse

determination of petitioners’ claim that the instant inter

pretation and application of this trespass statute by state

courts, excluding as an element of the crime any require

ment of “scienter” or “mens rea”, was violative of the

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Mr. Jus

tice Frankfurter’s statement in his concurring opinion in

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501, 510, is thus apropos

to the present posture of this matter:

“But when decisions by state courts involving local

matters are so interwoven with the decision of the

question of Constitutional rights that one necessarily

involves the other, state determination of local ques

tions cannot control the Federal Constitutional right.”

This petition seeks to present to this Court for its de

termination the question of whether the Commonwealth’s

instant interpretation and application of this statute is

permissible under the Constitution.

15

This Court has held that there are constitutional limita

tions upon the legislature in enacting and the judiciary in

interpreting and applying statutes so as to eliminate any

requirement of “scienter” or “mens rea” as a prerequisite

to criminal punishment. Morisette v. V. S., 342 IT. 8. 246.18

Where this Court has found that these constitutional lim

itations have been exceeded the convictions have been set

aside. Smith v. California, 361 IT. S. 147; Lambert v. Cali

fornia, 355 IT. S. 225; Morisette v. TJ. S., supra. In apply

ing these decisions it should be remembered that “scienter”,

“mens rea” or “knowledge” refer to actual distinctive states

of mind varying, of course, with the particular offense.

Jerome Hall, General Principles of Criminal Lain (2nd

Ed.) 1960, pp. 70-71. As Professor M. Perkins, Criminal

Law (1957) pp. 681-683, has suggested, since “scienter”

and “mens rea” are frequently employed as synonyms, and

since they have also been employed as a synonym of knowl

edge, the need, therefore, is to search for the state of mind,

or states of mind, which the courts have spoken of as

“knowledge.”

Though the distinctive states of mind which this Court

has found necessary vary with the particular offense, and

though these distinctive states of mind may be referred to

as “knowledge,” “mens rea,” “scienter,” or in other terms,

the decisions of this Court establish that there are Con

stitutional limitations on the power to eliminate “state of

mind” as an element of criminal conduct. The dissenting

Judges in Lambert v. California, supra, acknowledge, with

the majority, such limitations but only disagreed as to

whether the statute in question has transgressed the per

missible limits.

18 Mueller, On Common Law Mens Rea, 42 Minn. L. Rev. 1043,

observes that the “opinion by Mr. Justice Jackson ended the

spreading development of criminal liability without fault . . . ”

16

No justification has been proposed by the Commonwealth,

and it is submitted that none exist, for treating this offense

of trespass to land under the heading of “public welfare

offenses,” 19 or under that category of offenses where this

Court has approved strict liability. Permitting the ap

plication of the doctrine of strict liability to this trespassory

offense would signal a substantial alteration in the field

of criminal law and would imperil and undermine presently

existing constitutional safeguards on the exercise of the

state’s police power to punish for crime.

Whether the interpretation and application of the statute

here in a manner creating strict liability exceeded the due

process limitations suggested by this Court frequently

under the descriptive mental state of “knowledge,” the in

terpretation and application here was arbitrary and dis

criminatory. Griffin v. State, 351 U. S. 12, 18; Cole v.

Arkansas, 339 U. S. 196.

19 Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Col. L. Rev. 55 (1933).

Professor Sayre’s eight general categories may be summarized as

follows:

“ (1) Illegal sales of intoxicating liquor;

(a) sales of prohibited beverage;

(b) sales to minors;

(c) sales to habitual drunkards;

(d) sales to Indians or other prohibited persons;

(e) sales by methods prohibited by law;

(2) Sales of impure or adulterated food or drugs;

(a) sales of adulterated or impure milk;

(b) sales of adulterated butter or oleomargarine;

(3) Sales of misbranded articles;

(4) Violations of anti-narcotic acts;

(5) Criminal nuisances;

(a) annoyances or injuries to the public health, safety,

repose, or comfort;

(b) obstructions of highways;

(6) Violations of traffic regulations;

(7) Violations of motor-vehicle laws;

(8) Violations of general police regulations, passed for the

safety, health, or well-being of the community.”

17

It was arbitrary for the court below to refuse to apply

the law announced in Wise v. Commonwealth, 98 Va. 837,

to the instant case. Each of these petitioners was charged

wTith a violation of Title 18.1-173, Virginia Code 1950

(1960 Amendment) (supra, p. 3) in the following pertinent

language:

“that (petitioners) did, on the 10th day of June, 1960,

in said County without the authority of law, remain

upon the premises of another, after having been for

bidden to do so, either orally or in writing by the

person lawfully in charge thereof, unlawfully and

against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.”

(Emphasis supplied) (E. 1, 2).

In Wise v. Commonwealth, supra, the defendant was

charged with a violation of what is now Title 18.1-172

of the Virginia Code.20

These petitioners were charged in the language of “un

lawfully” as was the defendant in the Wise case. Thus

the necessary distinctive mental state required for con

viction of the petitioners was that required in the Wise

case. These petitioners sought to have the courts below

apply the same rule of law to them as was applied in the

Wise case. In the Wise case the Supreme Court of Ap

peals of Virginia stated in its opinion on pp. 838-839.

“At the trial the prisoner offered, but was not per

mitted, to prove by counts that this verbal contract

20 §18.1-172. Injuring, etc., any property, monument, etc.—If

any person, unlawfully, but not feloniously, take and carry away,

or destroy, deface or injure any property, real or personal, not his

own, or break down, destroy, deface, injure or remove any monu

ment erected for the purpose of marking the site of any engagement

fought during the War between the States, or for the purpose of

designating the boundaries of any city, town, tract of land, or any

tree marked for that purpose, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Virginia Code 1950 [1960 Amendment].

18

with respect to the disputed land had been trans

ferred to him. It is not pretended, of course, that

this verbal contract or understanding passed title,

but it does bear upon the bonafides of a claim of right

asserted by the prisoner, and should have been ad

mitted.”

“The prisoner asked the court to instruct the jury as

follows: ‘The court instructs the jury, if they believe

from the evidence that the defendant, John Wise,

pulled down the fence and left it down under a claim

of right, believing it to be his own, and believing that

he had a bonafide right thereto, then the jury shall find

for the defendant’.”

“This instruction propounds the law correctly, and

should have been given.” (Emphasis supplied.)

These convictions resulted from a failure to apply the

same rule of law to these petitioners as was applied in Wise.

This arbitrary and discriminatory action is a violation of

decisions of this Court.

In addition, the instant interpretation and application

arbitrarily eliminated the recognized principle of Anglo-

American criminal law of concurrence:

“The remaining step in the above indicated stages of

analysis of criminal conduct concerns situations where

there was a mens rea and an act and, also, a harm

of some sort, but still no penal liability because an

additional material element was missing, namely, the

fusion of the legally material thought and effort in

conduct, which Anglo-American criminal law des

ignates as “concurrence.” The principle of concurrence

requires that the mens rea (the internal fusion of

thought and effort) coalesce with the additional mani

19

fested effort (“act”), that they function externally as

a unit to comprise criminal conduct. As was previously

stated, this is a way of making certain that the de

fendant’s conduct was criminal, i.e. that his conduct

actually expressed a mens rea, The efforts of pros

ecutors to established concurrence by invoking the tort

rule of trespass ab initio, so that a. legal entry would

be found criminal because of the defendant’s subse

quent misconduct, have been unsuccessful.” Hall, su

pra, pp. 185-190.

Likewise, Perkins, supra, p. 725, observes that the doctrine

of trespass ab initio, firmly entrenched in the law of torts,

has no application in criminal jurisprudence. The “tres

pass after warning” statutes came into existence because

of the principle of concurrence. These statutes created

an act, “remaining,” which could concur with the nec

essary state of mind, “after warning.”

The instant interpretation and application by which

these convictions were obtained makes the statute so vague,

indefinite, and uncertain as to offend the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment as construed in applicable

decisions of this Court. Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S.

451; Winters v. N. Y ., 333 IT. S. 507. This Court has often

held that criminal laws must define crimes sought to be

punished with sufficient particularity to give fair notice

as to what acts are forbidden. As the Court held in Lan-

zetta v. N. J., supra, 453, “no one may be required at peril

of life, liberty or property to speculate as to the meaning

of penal statutes. All are entitled to be informed as to

what crimes are forbidden.” See also United States v. L.

Cohen Grocery, 255 U. S. 81, 89; Connally v. General Const.

Co., 269 U. S. 385; Raley v. Ohio, supra. The statutory

provision applied to convict petitioners in this case is so

vague that it offends the basic notions of fair play in the

20

administration of criminal justice that are embodied in the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Moreover, the statute punished petitioners’ protest

against racial segregation practices and customs in the

community; for this reason the vagueness is even more

invidious. When freedom of expression is involved the

principle that penal laws may not be vague must, if any

thing, be enforced even more stringently. Cantwell v.

Conn., 310 U. S. 296, 308-311; Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S.

344; Watkins v. U. S., 354 U. S. 178; Herndon v. Lowry,

301 U. S. 242, 261-264.

(1) This statute, as now interpreted and applied, is

indefinite as to what constitutes a valid right to enter or

remain. See Commonwealth v. Richardson, 313 Mass. 632.

(2) With “bona fide claim” eliminated as a defense to

the statute, there are no adequate statutory or other

guides to inform a reasonable man as to what he may or

may not do in terms of entering or remaining.

As this Court stated in Winters v. New York, supra,

520, a case which invalidated on the grounds of vagueness

a state law applied to limit free expression: “Where a

statute is so vague as to make criminal an innocent act,

a conviction under it cannot be sustained”. In this case

the state has indiscriminately classified and punished in

nocent actions as criminal. The result is an arbitrary exer

cise of the state’s power which offends due process. IFie-

man v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183, 191. The decision below

affirming these convictions is in conflict with decisions of

this Court testing statutes under the established criteria

of the “void for vagueness” doctrine. Jordan v. DeGeorge,

341 IT. S. 223.

21

B. The decision below affirming these convictions is in

conflict with prior decisions of this Court prohibit

ing racially discriminatory state action.

The testimony of the state’s own witnesses clearly

establishes that the two young Negro petitioners went into

a public restaurant, made certain purchases, but upon

seating themselves at a counter and requesting service,

even though persons who entered before, with and after

the petitioners were served without incident, petitioners

were denied service and requested by the owner to leave

the premises because he believed there was a law prohibit

ing the serving of colored people. It is clear that peti

tioners were refused service and asked to leave solely

because they were Negroes and stand convicted as a result

of the use of the state’s criminal process to effectuate a

policy and practice of racial discrimination. The peti

tioners’ race was the only basis for the police officer’s

command that they leave these premises and for the ar

rests which followed. Obviously this is the inference which

the jury had drawn from the evidence when they pro

pounded the question:

“Does ‘trespassing’ mean that a person can be asked

to leave a restaurant such as Howard Johnson’s, serv

ing the public, without cause” (Tr. 61)!

As long ago as Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, a

case involving a claim of discrimination in jury procedures,

this Court stated the broad proposition that racial dis

crimination in the administration of criminal laws violates

the Fourteenth Amendment. The court said at 162 U. S.

565, 591:

“The guaranties of life, liberty, and property are for

all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

or of any state, without discrimination against any

22

because of their race. Those guaranties, when their

violation is properly presented in the regular course

of proceedings, must be enforced in the courts, both

of the nation and of the state, without reference to

considerations based upon race. In the administration

of criminal justice no rule can be applied to one class

which is not application to all other classes.”

This Court has repeatedly struck down statutes and

ordinances which provided criminal penalties to enforce

racial segregation. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60;

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Gayle v. Browder,

352 U. S. 903, affirming 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala.

1956); State Athletic Commission v. Dorsey, 359 U. S. 533,

affirming 168 F. Supp. 149 (E. D. La. 1958), were all cases

in which criminal laws used to maintain segregation were

invalidated. Cf. Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202. Likewise,

in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, the Court nullified a

criminal prosecution under a statute which was fair on

it face but was being administered to effect a discrimina

tion against a single ethnic group.

While it may be argued by the Commonwealth that in

this case the racial discrimination against petitioners is

beyond the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment because it

originated with the decision of a “private entrepreneur”

to establish a “white-only” lunch counter in deference to

local customs and traditions, this is not dispositive of the

case because it is racial discrimination by agents of the

Commonwealth of Virginia which affords the primary basis

for these prosecutions. It was the police officer acting as

law enforcement representative of the Commonwealth who

commanded petitioners to leave their seats at the lunch

counter because petitioners were Negroes and the counter

was maintained for white people. It was the police officer

who arrested petitioners for failure to obey this command.

23

It was the public prosecutor who charged petitioners with

an offense, and it was the State’s judiciary that convicted

and sentenced them. Thus, from the policeman’s order,

the conviction and punishment, the Commonwealth was

engaged in enforcing racial segregation with all of its law

enforcement machinery.

This racial discrimination may fairly be said to be the

product of state action within the reach of the Fourteenth

Amendment which “nullifies and makes void all State

legislation, and State action of every kind, which impairs

the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United

States, or which injures them in life, liberty or property

without due process of law, or which denies to any of

them the equal protection of the laws.” Civil Rights Cases,

109 U. S. 3, 11. As stated by the Court in Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 17:

“Thus the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment

extend to all action of the State denying equal pro

tection of the laws; whatever the agency of the State

taking the action, . . . (citing cases) . . . ; or whatever

the guise in which it is taken, . . . (citing cases).”

Just as judicial enforcement of racially restrictive cov

enants was held to constitute state action in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, so in this

case judicial enforcement of a rule of racial segregation

in privately owned lunch counters operated as business

property opened up for use by the general public should

likewise be condemned.

In Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715, 722, Mr. Justice Clark, delivering the opinion of the

Court, stated:

24

“Because the virtue of the right to equal protection of

laws could lie only in the breadth of its application, its

constitutional assurance was reserved in terms whose

imprecision was necessary if the right were to be en

joyed in the variety of individual-state relationships

which the Amendment was designed to embrace. For

the same reason, to fashion and apply a precise

formula for recognition of state responsibility under

the Equal Protection Clause is ‘an impossible task’

which ‘this Court has attempted.’ Koteh v. Board of

River Port Pilot Com’rs, 330 U. S. 552, 556, 67 S. Ct.

910, 912, 91 L. Ed. 1093. Only by sifting facts and

weighing circumstances can the nonobvious involve

ment of the State in private conduct be attributed its

true significance.”

And as Mr. Justice Frankfurter observed in his dissent,

727:

“For a State to place its authority behind discrimina

tory treatment based solely on color is indubitably a

denial by a State of the equal protection of the laws,

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

By the interpretation and application of the trespass stat

ute under the circumstances here the Commonwealth has not

merely placed its authority behind discriminatory treat

ment based solely upon race, but the Commonwealth has so

involved itself in thus employing its criminal process and

thereby erecting criminal sanctions that it now stands en

meshed. Under prior decisions of this Court, these convic

tions resulted from invalid state action.

25

C. The decision below affirming these convictions is in

conflict with or in advance of this Court’s decisions

prohibiting unwarranted state interference with the

exercise of rights protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Independent of any question of the racially discrimina

tory use of its criminal process, this Court has held that

the employment of the state criminal process is prohibited

state action where its use amounts to prohibitive interfer

ence with the exercise of constitutional rights. Marsh v.

Alabama, supra. The employment of the criminal ma

chinery by the Commonwealth was an unwarranted interfer

ence with the enjoyment of the rights of expression and of

association, the right to secure property, and the right to

the enjoyment of liberty which are guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.

In the Marsh case, supra, after the Supreme Court estab

lished that the defendants had a right to distribute religious

literature upon the private premises of a company owned

town, the Court found that the use of the state’s criminal

machinery to punish or impede those in the exercise of that

right was unconstitutional. That is to say, statutes other

wise valid are invalidly applied in such situations. Tick Wo

v. Hopkins, supra.

In the celebrated case of Cunningham v. Neagle, 135 U. S.

1, the Supreme Court reviewed the problem of the use

of the state criminal process to impede, hamper and frus

trate the exercise of the national power. The court re

affirmed the proposition that the State’s police power was

subject to the Supremacy Clause of the United States Con

stitution. Art. VI, cl. 2. The Court stated at 70 and 72:

“ . . . the prisoner is held in the state court to answer

for an act which he was authorized to do by the law of

the United States, which it was his duty to do as Mar

26

shal of the United States, and if in doing that act he

did no more than what was necessary and proper for

him to do, he cannot be guilty of a crime under the

law of the State of California.”

Where there had been an exercise of the criminal process

or a threat to exercise such process, even as remote as

criminal sanction by way of contempt following injunctive

relief for conduct protected by the First Amendment, the

Supreme Court has prohibited such state intervention.

Watson v. Jones, 13 Wall. 679 ; Cantwell v. Connecticut,

supra; Murdoch v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105; Davis

v. Balson, 133 U. S. 333; Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire,

315 U. S. 568; Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454; Near

v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697; Jones v. Opelika, 319 U. S. 103;

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353.

Petitioners entering and remaining upon the premises of

this public restaurant sought to procure service under the

same circumstances and conditions of other patrons and

upon refusal to demonstrate and convey to others knowl

edge of racial discriminatory treatment in the expectation

that an orderly change of policy would ensue as a result of

the dissemination of this information by this form of pro

test. Their expression (asking for service) was entirely

appropriate to the time and place in which it occurred.

Certainly the invitation to enter an establishment carries

with it the right to discuss and even argue with the pro

prietor concerning terms and conditions of service so long

as no disorder or obstruction of business occurs.

Petitioners did not shout, obstruct business, carry picket

ing signs, give out handbills, or engage in any conduct

inappropriate to the time, place and circumstances. There

was no invasion of privacy involved in this case, since the

27

lunch counter was an integral part of commercial property

open up to the public.

The liberty secured by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment insofar as it protects free expres

sion is hardly limited to verbal utterances. It covers picket

ing, Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. 8. 88; free distribution

of handbills, Martin v. Struthers, supra; display of mo

tion pictures, Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495; joining

of associations, N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449;

the display of a flag or symbol, Btromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359. What has become known as a “sit in” is a

different but obviously well understood symbol, a mean

ingful method of communication.

This “sit in” occurred in a place entirely open to the

public and to petitioners as well. That the p r e m i ses were

privately owned should not detract from the high constitu

tional position which such free expression deserves. This is

hardly a case involving, for example, expression of views

in a private home or other restricted area private in nature.

The establishment here was open to the public and the pa

tronage of the public, including that of Negroes was sought.

This Court in the Marsh case supra, 506, rejected argu

ment that being present upon private property per se

divests a person of the constitutional right of free ex

pression :

“Ownership does not always mean absolute d o m i n i on

The more an owner, for his advantage, opens up his

property for use by the public in general, the more do

his rights become circumscribed by the statutory and

constitutional rights of those who use it. . . . ”

In that case this Court held unconstitutional convictions

of Jehovah’s Witnesses for trespass for proselytizing on

private property of a company town. See also, Republic

Aviation Corp. v. National Labor Relations Board, 324

U. S. 793, 801, note 6; National Labor Relations Board

v, Babcock and Wilcox Co., 351 U. S. 105, 112; United

Steelworkers v. National Labor Relations Board, 243 F.

2d 593, 598 (D. C. Cir. 1956), rev. on other grounds, 357

U. S. 357; People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N. Y. S. 2d

277, 279 (1948) ; Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, 45 Lab.

Bel. Bef. Man. 2334 (Wash. Super. Ct. 1959).

These decisions, of course, are manifestations of the

fundamental view, stated in Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113,

126, that “when . . . one devotes his property to a use in

which the public has an interest, he, in effect, grants to the

public an interest in that use, and must submit to be con

trolled by the public for the common good, to the extent of

the interest he has thus created.. . . ”

As this Court stated in Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S.

516, 524:

“Where there is a significant encroachment upon per

sonal liberty, the State may prevail only upon showing

a subordinating interest which is compelling.”

There is no showing, and there can be none, of a controlling

justification for the limitation upon freedom of expression

and association which this interpretation and application

of the trespass law imposes. N. A. A. C. P. v. State of

Alabama, supra.

Therefore, having no valid interest to preserve, the

Commonwealth has no power to interfere by use of its

criminal process with the expression and association in

which petitioners were engaged.

The dedication of the property involved in this restau

rant business altered the rights of the owner and members

of the public. The state’s action here was an unwarranted

29

infringement upon petitioners’ right to contract, to secure

property and to otherwise enjoy the liberties of free men

unimpaired by the action of the state. In Valle v. Stengel,

176 Fed. 2d 697, 703, the court stated:

“If a man cannot make or enforce a contract already

made because of the interference of a State officer he

is being denied a civil right. He cannot support him

self or his family or earn a living under the system

to which we adhere. The liberty involved is in fact the

liberty of the contract. Cf. Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165

U. S. 578, 17 S. Ct. 427, 41 L. Ed. 832. To refuse to

an individual the liberty of contract is to put him be

yond the pale of capitalism. Thus ostracized, he can

not engage in the acquisition of property or in the

pursuit of happiness.”

And as this Court observed in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S.

497:

“Although the Court has not assumed to define ‘liberty’

with any great precision, that term is not confined to

mere freedom from bodily restraint. Liberty under

law extends to the full range of conduct which the

individual is free to pursue, and it cannot be restricted

except for a proper governmental objective. Segrega

tion in public education is not reasonably related to

any proper governmental objective, and thus it im

poses on Negro children of the District of Columbia

a burden that constitutes an arbitrary deprivation of

their liberty in violation of the Due Process Clause.”

30

Finally, that this private restaurant which is open for

the public is not an untouchable island in our midst because

of its dedication is too clear to be debated. This restaurant

is subject to myriad laws and regulations; and that it is

affected with a public interest is everywhere apparent; and,

much more important it must also be operated in accord

with the law of the land which includes a prohibition against

racially discriminatory state action. No power to cut off

the food and drug supply from millions of Americans can

possibly be said to reside either in the mercurial protection

of the merchant’s self interest or his prejudicial aberrations.

These petitioners, then, had a right to be in this restau

rant and to be served as others, and only reasonable grounds

for exclusion or refusal to serve could revoke the enjoy

ment of this right with state sanction or assistance. It is

submitted that race or color is not such a reasonable basis.

Thus the state sanction and assistance by these arrests and

convictions was an unwarranted infringement upon rights

of petitioners of expression and of association, the right

to contract and to secure property, and to otherwise enjoy

the liberties of free men, guaranteed by the Constitution.

31

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

H erbert 0 . R eid

1500 Newton Street, N. E.

Washington, D. C.

Attorneys for Petitioners

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

E lwood H. Chisolm

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Of Counsel

la

A PPEND IX

V irginia:

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Bichmond on

Tuesday the 25th day of April, 1961.

The petition of Lawrence George Henry for a writ of

error and supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the

Circuit Court of Arlington County on the 3rd day of No

vember, 1960, in a prosecution by the Commonwealth

against the said petitioner for a misdemeanor, No. 2754,

having been maturely considered and a transcript of the

record of the judgment aforesaid seen and inspected, the

court being of opinion that the said judgment is plainly

right, doth reject said petition and refuse said writ of

error and supersedeas, the effect of which is to affirm the

judgment of the said circuit court.

A Copy,

Teste:

/ s / H. G. Turner

Clerk

2a

V irginia :

In the Supreme Court of Appeals held at the Supreme

Court of Appeals Building in the City of Richmond on

Tuesday the 25th day of April, 1961.

The petition of Dion Tyrone Diamond for a writ of error

and supersedeas to a judgment rendered by the Circuit

Court of Arlington County on the 3rd day of November,

1960, in a prosecution by the Commonwealth against the

said petitioner for a misdemeanor, No. 2755, having been

maturely considered and a transcript of the record of the

judgment aforesaid seen and inspected, the court being of

opinion that the said judgment is plainly right, doth reject

said petition and refuse said writ of error and supersedeas,

the effect of which is to affirm the judgment of the said

circuit court.

A Copy,

Teste:

/ s / H. G. Turner

Clerk