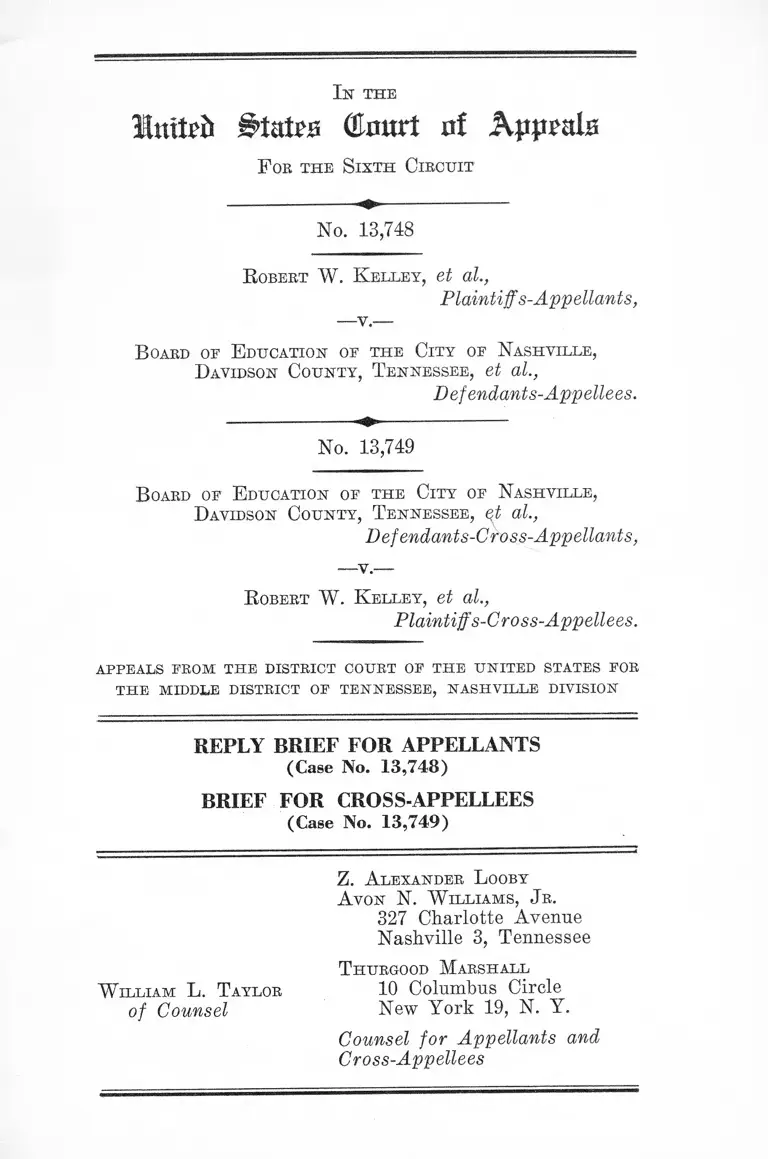

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Reply Brief for Appellants and Cross-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Reply Brief for Appellants and Cross-Appellees, 1958. e17b93c2-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77cf7765-e0d6-4560-b8ee-162cf035e2df/kelley-v-metropolitan-county-board-of-education-of-nashville-and-davidson-county-tn-reply-brief-for-appellants-and-cross-appellees. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

luitrti i>tatP0 ©nurt uf Apprats

F ob the S ixth Circuit

No. 13,748

R obert W. K elley, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

B oard of E ducation of the City of Nashville,

Davidson County, Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 13,749

B oard of E ducation of the City of Nashville,

Davidson County, Tennessee, qt al.,

Defendants-Cross-Appellants,

R obert W. K elley, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Cross-Appellees.

appeals from the district court of the united states for

T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

(Case No. 13,748)

BRIEF FOR CROSS-APPELLEES

(Case No. 13,749)

Z. Alexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood Marshall

W illiam L. T aylor 10 Columbus Circle

of Counsel New York 19, N. Y.

Counsel for Appellants and

Cross-Appellees

In th e

Hniteft Hfliirt at Kppml#

F or the Sixth Circuit

No. 13,748

R obert W. K elley, el al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v.-

B oard oe E ducation oe the City of Nashville,

Davidson County, Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e d i s t r i c t c o u r t o f t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s f o r

T H E M ID D LE D IST R IC T OF T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement

Appellees’ “Counter-Statement of Facts” is devoted not

to the development of additional material facts to aid this

Court in rendering a decision or to the correction of in

accuracies in appellants’ statement of facts but rather to

mere insinuations of misrepresentation and omission. That

the “Counter-Statement of Facts” does not alter or add

materially to the facts as stated by appellants appears on

its face. In view of the length of the record, however, ap

pellants deem it important to reply to certain points raised

by appellees.

2

I. Despite the assertions of appellees, the Statement

of Facts refers to all opinions rendered by the Court below

except one (in a collateral proceeding not involving the

validity of appellees’ actions but rather the restraint of

persons seeking to interfere with desegregation). Appel

lants’ Appendix contains all of these opinions and the ac

companying findings of fact and conclusions of law, with

the single exception of the opinion of a three-judge court

referring the case to a single judge, relevant portions of

which are included in another opinion (App. 47a) and re

ferred to in the Statement of Facts.

II. As hereinafter more fully appears, no material facts

were developed at the hearing on November 13-14, 1956

which were not presented at subsequent hearings and dis

cussed in appellants’ brief.

III. Appellees make numerous references to what they

deem to be insufficient attention paid to the fact that the

Court below found at various stages in the proceedings

that they had acted in good faith. Appellants never dis

puted the fact that such finding was made—-a holding of

good faith was of course implicit in the Court’s sustention

of appellees’ plan. Appellants merely pointed out that on

February 18, 1958 the Court found that the Board of Edu

cation was committed to a policy of continued segregation

and documented this conclusion with a list of the Board’s

attempts to delay (App. 94a). In this connection, it is

ironic that appellees seek to place so much stress on their

good faith in promulgating their plan in the same brief in

which they seek to discard that plan entirely and substi

tute a scheme for segregated white schools to which Negro

students would be denied admission solely because of race.

Moreover, when appellees first presented this scheme to

the Court below, they characterized it as “a complete plan

to abolish segregation” and urged that it differed in signifi

3

cant respects from Chapter 11, Public Acts of Tennessee

for 1957, which the Court had already ruled unconstitu

tional (App. 97-101a). Appellees now drop the pretense

and admit on page 30 of their brief that their plan and

Chapter 11 are substantially the same and that the plan

was offered “to preserve for appellate review the consti

tutional question as to Chapter 11.”

IV. Appellees assert that the finding of substantial phys

ical equality of facilities for white and Negro students

contradicts statements in appellants’ brief. They neglect

to point out that the finding they refer to was made in

1956 and that at the April, 1958 hearing, the Superintendent

of Schools under questioning by the Court, frankly ad

mitted that certain facilities provided for white children

were not provided for Negro children (App. 228-229a).

How the physical equality of facilities, even if demon

strated, would justify an extension of time for desegrega

tion, appellees do not explain.

V. Although appellees attempt to make it appear that

administrative obstacles were raised in 1956 which were

not revealed in appellants’ brief, this is clearly not the

case. Teacher attitudes and the problem of achieving

homogeneous groupings based upon achievement levels and

other factors, were both raised at the 1958 hearings and

discussed in detail in appellants’ brief. The only other

obstacle mentioned was “problems arising from a lib

eralized transfer system.” That racial transfer system

is here challenged, and the “problems” arising from it are

nowhere identified by appellees. Neither is it suggested,

with respect to this, or any other matter, that twelve years

will permit the taking of any specific step to overcome the

problem. Appellees assume throughout their brief that

a mere listing of “problems” is all that is necessary to

support the granting of a twelve year delay and that they

have no responsibility for demonstrating that the time

4

sought is related to the solution of these “problems” or for

proposing specific steps to overcome them.

VI. Appellees claim that the undisputed evidence shows

that “the achievement level of white students in the Nash

ville schools is substantially higher than such level of

Negro students in the same grade,” and that this evidence

conflicts with appellants’ assertion that the achievement

levels of Negro students are not uniformly below those of

white students. It is not clear whether appellees intend

by this statement to contend that all Negro students in a

particular grade are below the achievement level of all

white students. Such a contention would of course have

no basis in fact (App. 189-190a).

Here again, appellees make no effort to show a connection

between the alleged disparity in achievement level and the

need for a twelve-year delay. Whatever the relevance of

appellees’ contentions, they hardly suggest that a solution

is to be found in depriving all children now in the schools

of their right to a nonsegregated education.

VII. Appellees make much of the opinion of one of their

witnesses that it has been “difficult to consolidate schools

even when they were relatively equal in ability and back

ground.” It is difficult to determine what importance ap

pellees attach to this general statement, but insofar as they

believe it supports their twelve-year plan, it must be read

in the light of evidence pertaining to actual experience with

desegregation in Baltimore, Washington, D. C., Kansas

City, Louisville, St. Louis, and other cities (App. 172-176a,

210-213a).

VIII. Appellees take issue with the appellants’ failure to

include in the Statement of Facts certain findings of fact

made by the Court after the hearing on April 14, 1958.

Appellees well know that these findings were repeated

verbatim in the Court’s opinion which is included in the

5

appendix with the findings of fact, referred to in the State

ment of Facts, summarized and quoted. What appellees

find inadequate they do not say.

Argum ent

I

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 3 L. ed. 2d 5, 10, the

Supreme Court, reaffirming its decision in Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U. S. 294, specifically ruled that hostility

to racial desegregation is not a relevant factor in determin

ing whether justification exists for not requiring immediate

nonsegregated education. There was no implication any

where in the opinion that such hostility might become rele

vant if connected in some way with the educational pro

gram. Appellees’ proposition that hostility may be con

sidered if put in other terms was specifically rejected in

the Court of Appeals in Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 34

(8th Cir. 1958) and argued unsuccessfully in the Supreme

Court. For a court to recognize such a proposition, would

of course, rob the ban on consideration of hostility to racial

desegregation of any real meaning.

Appellees contend that if they are not permitted to con

sider community hostility to desegregation in formulating

a plan, they will be denied the “constructive use of time.”

But it was specifically to assure that time would be used

constructively that consideration of community hostility

was forbidden. What happens when this rule is not ob

served is well demonstrated by this case. Time is sought

not so that it may be used constructively to permit solu

tion of specific problems and accomplish desegregation at

the earliest practicable date, but simply for the sake of

delay.

6

II

In seeking to sustain the validity of their racial transfer

provision, appellees put forward the novel theory that the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment has no application to acts of a state agency

giving effect to the prejudices of private persons. They

make no attempt to develop or document this argument—

nor could they, for it is well established that the reach of

the Fourteenth Amendment extends to state action effec

tuating private discrimination. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249; cf. Pennsyl

vania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of Phila., 353

U. S .230.

Appellees also say that to hold their racial transfer

plan unconstitutional it is necessary to assume that one

pupil has a constitutional right that another pupil be com

pelled to attend school in his geographic zone. No such

assumption is necessary or implicit. Appellants seek only

to attend school on the same terms as other students, with

out regard to race. If appellees wish to adopt a free trans

fer or registration provision which would allow both white

and Negro students to enroll in or transfer to the same

schools outside their geographic zones, it would not be

subject to attack. This type of assignment system was

adopted in Baltimore and the statement of Dr. Carmichael,

relied on by appellees, clearly refers to this nonracial

system rather than to a racial provision.

No sentence in Clemons v. Board of Education of Hills

boro, 228 F. 2d 853 (8th Cir. 1956), however lifted out of

context, supports appellees’ contention that it is proper

for a school board to require Negro children to attend

schools in their geographic area while allowing white

children in the same area to transfer to other schools,

solely because of their race.

7

When appellees seek to sustain their transfer provision

as one based on “voluntary choice,” they clearly mean the

voluntary choice of white parents only. They argue, in

effect, that if all white parents elect to have their children

attend segregated schools and all Negro parents elect to

have their children attend desegregated schools, a school

board could with impunity establish only segregated schools

on the ground that to do otherwise would amount to “en

forced integration.” But the use of catchwords like “en

forced integration” or “proximity to local conditions” is

hardly dispositive of the constitutionality of state action

authorizing the assignment or transfer of children to

schools on the basis of race.

Ill

Appellees, obliquely challenging appellants’ right to cite

non-legal authorities in an appellate brief, characterize

these authorities as of “dubious value,” and reiterate their

charges that appellants have misrepresented the facts. Ap

pellees apparently deem this mode of advocacy a satisfac

tory substitute for meeting the substance of appellants’

arguments. But appellants obviously do not consider one

of appellants’ main sources to be “dubious,” for they cite

Dr. Carmichael in their own brief (p. 17), albeit for a point

that does not support their argument. Appellees also neg

lect to note that each proposition for which race rela

tions authorities are cited is also supported by the testi

mony of appellants’ witnesses at trial (App. 177-178a, 197-

200a, 210-211a). Finally, appellees do not deem it neces

sary or appropriate to disclose in what respect they differ

with the conclusion that a twelve-year plan is not a good

method for overcoming community antagonism, or the facts

adduced to support this conclusion.

In their discussion of Moore v. Board of Education of

Harford County, 152 F. Supp. 114 (D. Md. 1957), aff’d

8

sub nom. Slade v. Board of Education of Harford County,

252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 357 U. S. 906,

appellees carefully omit any mention of the fact that under

the approved plan eleven of the eighteen elementary schools

in Harford County were to be completely desegregated

immediately and that immediate provision was made for the

transfer of qualified students in high school pending the

final elimination of segregation.

Appellees again rehearse their accusation that appel

lants suppressed material facts in their brief. But again

the only problems suggested involve teacher attitudes and

achievement levels. The opposition of teachers to de

segregation even if established is no more a relevant fac

tor to be considered than hostility of the general com

munity. Recognition of the antagonism of teachers as a

relevant factor could give rise to indefinite delay. Appel

lees do not reveal how it was determined that first grade

teachers are prepared to teach desegregated classes now

while. high school teachers will not be ready for ten to

twelve years.

Nor do appellees show how alleged disparities in achieve

ments levels are related to a twelve-year delay. The only

inference to be drawn from appellees’ argument is that

white and Negro children who have never attended segre

gated schools can be taught together when they enter the

school system but that after only one year of segregated

education, the disparity of white and Negro achievement

levels is so great that there is justification for forever de

priving Negro children of the right to a nonsegregated

education. If true, this would merely constitute an addi

tional indictment of segregated schools. But appellees cite

no evidence to show that differences in achievement levels

are so great as to make it impracticable to allow any child

now attending a segregated school in Nashville ever to at

tend a desegregated school.

9

In sum, appellees contend that a finding of good faith

and of community hostility to desegregation, when added

to a general statement that problems exist, unaccompanied

by any tie between the alleged problems and the delay

sought, or by specific proposals for overcoming these prob

lems, is all that is necessary to warrant the granting of a

twelve-year delay. Appellants submit that a whole genera

tion of school children cannot so easily be deprived of their

constitutional rights and that the granting of a twelve-year

delay under such circumstances can hardly be said to be

“desegregation at the earliest practicable date.”

Respectfully submitted,

Z. Alexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood Marshall

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Counsel for Appellants

W illiam L. Taylor

of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF BRIEF

(Case No. 13,749)

PAGE

Counter-Statement of Question Involved ................. 11

Statement of Facts ..................................................... 12

Argument ....................................................................... 12

Relief.............................................................................. 13

T a b l e op C a s e s :

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) .............. 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 ............... 12

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ..................................... 12

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956) .. 12

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Va.

1948) .......................................................................... 13

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of

Philadelphia, 353 IT. S. 230 ................................... 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 .................................. 13

Tate v. Department of Conservation and Development,

133 F. Supp. 53 (E. D. Va. 1955), aff’d 231 F. 2d 615

(4th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 352 U. S. 838 ..........12-13

In THE

Imtefr ( ta r t at Appeals

F oe the S ixth Circuit

No. 13,749

B oard oe E ducation of the City of Nashville,

Davidson County, Tennessee, et al.,

T)ef endants-Cross-Appellants,

-v.—

R obert W. K elley, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Cross-Appellees.

A PPEA L FR O M T H E D IST R IC T COU RT OF T H E U N IT E D STA TES FO R

T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

BRIEF FOR CROSS-APPELLEES

Counter-statem ent o f Q uestion Involved

Does a plan which authorizes the establishment of state-

operated schools for white children whose parents desire

that they attend segregated schools violate the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution by denying

to Negro children the right to enter said schools, solely be

cause of their race?

The Court below answered this question Yes. Cross-

Appellees contend that this answer was correct.

12

Statem ent o f Facts

Cross-appellees accept tlie statement of facts in the brief

of cross-appellants.

Argum ent

Does a plan which authorizes the establishment of state-

operated schools for white children whose parents desire

that they attend segregated schools violate the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution by denying

to Negro children the right to enter said schools, solely

because of their race!

The Court below answered this question Yes. Cross-

Appellees contend that this answer was correct.

In the School Segregation Cases, the Supreme Court held

that “racial discrimination in public education is unconsti

tutional” and that “[a]ll provisions of federal, state, or

local law requiring or permitting such discrimination must

yield to this principle” Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294, 298.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 3 L. ed. 2d 5, 17, the

Supreme Court said:

“State support of segregated schools through any

arrangement, management, funds, or property cannot

be squared with the Amendment’s command that no

State shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.”

Cross-appellants could not, without violating the Four

teenth Amendment, allow private persons to maintain

segregated schools by leasing public facilities to them.

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958); cf. Bar

rington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956); Tate v.

13

Department of Conservation and Development, 133 F. Supp.

53 (E. D. Va. 1955), aff’d 231 F. 2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied 352 U. S. 838; Lawrences. Hancock, 76 F. Supp.

1004 (S. D. W. Ya. 1948). Nor could they provide assistance

to private persons operating segregated schools, without

contravening the Fourteenth Amendment. Pennsylvania

v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of Phila., 353 U. S.

230; cf. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

In the face of this, cross-appellants assert that they have

a right to operate and maintain openly a system of segre

gated schools to which children are denied admission solely

because of race. This contention, we submit, is insupport

able.

R elie f

For the reasons hereinabove indicated, it is respect

fu lly subm itted that the judgm ent o f the Court below

should be affirm ed.

Respectfully submitted,

Z. A lexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood Marshall

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Counsel for Appellees

W illiam. L. Taylor

of Counsel

38