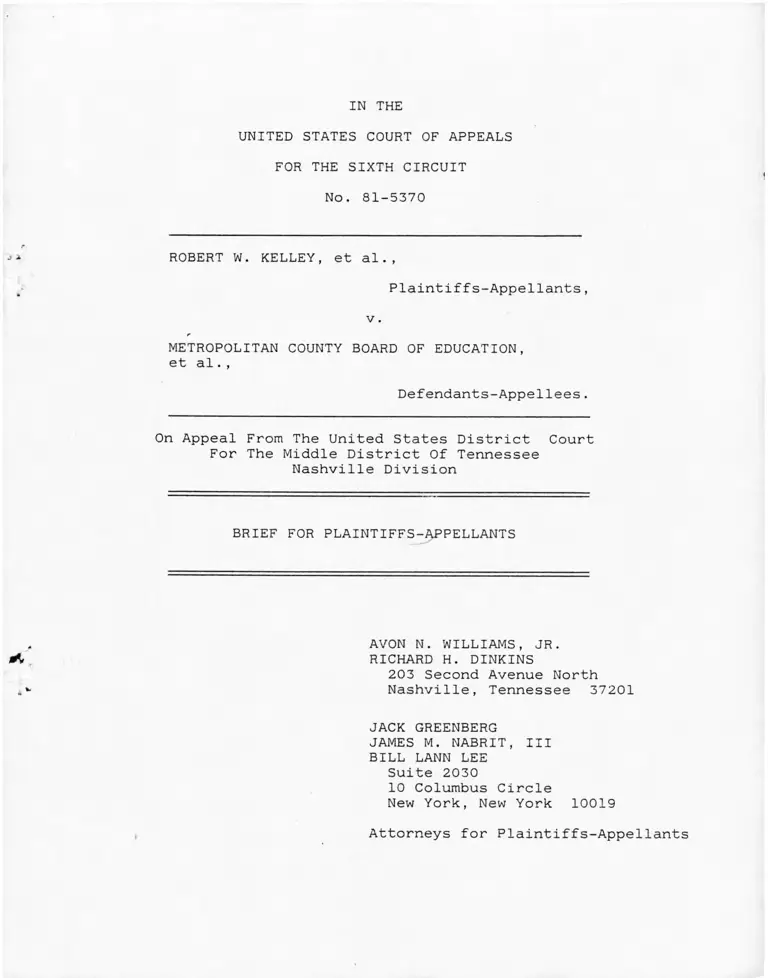

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 30, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1981. 90ed2fa9-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77e66e1c-aa65-4f0e-88d5-be12d44aa724/kelley-v-metropolitan-county-board-of-education-of-nashville-and-davidson-county-tn-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-5370

ROBERT W. KELLEY, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of Tennessee

Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

RICHARD H. DINKINS

203 Second Avenue North

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

I N D E X

Questions Presented ................................. 1

Statement ............................................ 2

A. Prior Proceedings ........................... 2

B. The 1971 Remedial Order ..................... 6

C. Proceedings Since the July 1971 Remedial Order 11

1. 1972-1978 Proceedings ................... 11

'2. 1979-1981 Proceedings ................... 18

D. The Board's 1981 Plan ....................... 24

Argument ............................................. 30

I. The Duty of Defendant School Board and the

District Court Was "'To Come Forward With a

Plan That Promises Realistically to Work ...

Now ... Until It Is Clear That State-Imposed

Segregation Has Been Completely Removed.'" .... 32

II. The District Court's Remedial Order Per

petuated or Reestablished a Dual System in

Violation of the Constitution................. 36

A. The Order Resegregated K-4 Elementary

Schools.................................... 36

B. The Order's 15% Minimum Presence Standard

Is Resegregative.......................... 41

C. The Order Imposes a Disproportionate

Burden of Busing on Black Middle School

Students.................................. 45

D. The Failure to Retain and Develop Pearl

High School as a Comprehensive Senior High

School Is Discriminatory and Impedes Desegregation............................. 47

III. The District Court's Failure to Consider the

Issues of Faculty and Staff Hiring and Assign

ment, Defendant's Contempt, and Plaintiffs'

1975 Motion for Counsel Fees and ExpensesWas Erroneous....................... 4g

Conclusion ............................... 50

Page

i

Table of Cases

Adams v. United States, 620 F .2d 1277 (8th Cir.

1980) 38

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

369 U.S. 19 (1969) 5

Anderson v. Dougherty County Board of Education,

609 F . 2d 225 (5th Cir. 1980) 36,4-1

Arthur v. Nyquist, 636 F. 2d 905 (2d Cir. 1981) ..... 4-5

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District,

4-95 ' F . 2d 4-99 (55h Cir.); 4-96 F . 2d 1309 (5th

Cir. 1972) 38,25

Brown v. Board of Education, 327 U.S. 283 (1952) 38

Brown v. Board of Education, 329 U.S. 292 (1952) 38

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 223 U.S. 229

(1979), affirming, 583 F .2d 787 (6th Cir.

1978) passim

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, 202 U.S.

33 (1971) 38,23

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 223 U.S.

526 (1979) .................................... 32,28

Evans v. Buchanan, 555 F.2d 373 (3d Cir. 1977),

aff'g, 216 F. Supp. 328 (D. Del. 1976) 38

Flax v. Potts, 262 F . 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1972) 37

Geier v. University of Tennessee, 597 F.2d 1056

(6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 222 U.S.

886 (1980) .................................... 28

Goss v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 231 (1963) ..... 5

Green v. County Board of Education, 391 U.S. 231

(1968) 5,32,32,20

Haney v. County Board of Education, 229 F.2d 362

(8th Cir. 1970) 29

Haycraft v. Board of Education, 585 F.2d 803 (6th

Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 223 U.S. 915 (1979) .... 29

Page

- li -

Higgins v. Board of Education, 508 F.2d 779 (6th

Cir. 1974-) 40,43

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 521 F.2d 465

(10th Cir. 1975) 38

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 616 F.2d

805 (5th Cir. 1980) 39,48

Lee v. Tuscaloosa City School System, 576 F .2d 29

(5th Cir. 1978) 41

McPherson v. School District No. 186, 426 F. Supp.

173 (S.D. 111. 1976) 38

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (197 7) ............ 37

Mills v. Polk County Board of Public Inst., 575

F . 2d 1146 (5th Cir. 1978) ....................... 37

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) 40,45

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 581 F.2d 581(6th Cir. 1978) ................................. 49

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir. 1976) .... 38

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F.2d 1042

(6th Cir.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 997 (1977) .... 45

Penick v. Columbus Board of Education, 583 F.2d 787

(6th Cir. 1978), affirmed, 443 U.S. 449 (1979) ... 43

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) .... 35

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,402 U.S. 1 (1972) ............................... passim

United States v. Board of Education of Valdosta,

576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 439

U.S. 1007 (1978) ............ .................... 36

United States v. Columbus Municipal Separate School

District, 558 F. 2d 228 (5th Cir. 1977) .......... 45

United States v. DeSoto Parish School Bd., 574 F.2d

804 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 982 36

United States v. School District of City of Ferndale,

499 F. Supp. 367 (E.D. Mich. 1980) .............. 45

Page

- iii -

Page

United States v. South Park Ind. School Dist.,

566 F. 2d 1221 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 4-39

U.S. 1007 (1978) 36

United States v. State of Texas, 498 F. Supp. 1356

(E.D. Tex. 1980) 38,46

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 532 F.2d

380 (5th Cir.), remanded on other grounds,

429 U.S. 990 (1976), cert, denied, 443 U.S.

915 (1979) 38,40

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 467 F.2d

848 (5th Cir. 1972) 48

IV

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-5370

ROBERT W. KELLEY, et al.,

Plaint iffs-Appellants,

v.

METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Tennessee

Nashville Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district court erred in approving and

substituting, for a comprehensive school desegregation plan

consistent with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971), and other authority, previously ordered

by the district court and approved by this Court, a "different

remedy," which, on its face,

(a) substantially resegregates grades K-4;

(b) imposes a 15% either race minimum presence

as a desegregation standard;

(c) imposes a disproportionate burden of trans

portation on black school children in

grades 5-8; and

(d) fails to retain and develop Pearl High School, the only remaining historically

black high school, as a comprehensive

senior high school.

2. Whether the district court erred in postponing in

definitely consideration of the issues of faculty and staff

hiring and assignment, defendants' contempt of provisions of the

prior desegregation plan, and plaintiffs' 1975 motion for counsel

fees and expenses.

STATEMENT V

A. Prior Proceedings

This school desegregation action was originally filed by

black school children in 1955 to enjoin state imposed racial

segregation in the public schools of Nashville, Tennessee, "on

the heels of the United States Supreme Court's decision in

2/Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)." Kelley

v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville, M.D. Tenn., Civ.

No. 2904. After the board conceded the unenforceability of

State constitutional and statutory separate school provisions,

a three-judge court was dissolved and the case remanded to the

district court for the framing of relief. 139 F. Supp. 578

1/ The history of the litigation and its relationship to developing school desegregation law through 1971 is set forth

in the Court's 1972 opinion, 463 F.2d 732, 735-740.

References to the Record on Appeal transmitted on October 10,

1981 are to "R.", to the Record on Appeal transmitted on August

25, 1981 are to "S.R.", and to the Joint Appendix are to "A."

2/ 463 F.2d at 375.

2

(1956). In January 1957, the court approved a desegregation

plan assigning first graders beginning in 1957-58 to schools

on the basis of geographic attendance zones subject to the

parents' rights to transfer the student to another school

attended by those of the student's own race. 2 Race Rel. L.

3/Rep. 21. The court required a plan for the remaining

grades by the end of 1 957. I_d. In the interim, the State

enacted legislation authorizing "separate schools for white and

negro children whose parents, legal custodians or guardians

voluntarily elect that such children attend school with members

of their own race," which the court declared facially unconstitu

tional. 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 970 (1957). Nonetheless, the board

moved to dismiss the action in reliance on administrative remedy

provisions of the legislation, and for approval of a desegrega

tion plan embodying the statute's provisions. The court denied

the motions, and gave the board a further opportunity to submit

3/ The plan provided, in pertinent part, that:

5. The following will be regarded as some of

the valid conditions to support application

for transfer:

(a) When a white student would otherwise

be required to attend a school previ

ously serving colored students only.

(b) When a colored student would otherwise

be required to attend a school previ

ously serving white students only.

(c) When a student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school where the

majority of students of that school

or in his or her grade are of a dif

ferent race.

3

a plan. 159 F. Supp. 272 (1958). The board then submitted a

plan calling for desegregation of an additional grade each

school year beginning with the second grade in 1958-59, subject

to the same racial transfer provisions previously approved. The

plan was approved over plaintiffs' objection, 3 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 651 (1958), affirmed, 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

4/361 U.S. 924 (1959). Minimal desegregation actually resulted.

In 1960, a parallel action was filed to desegregated the

Davidson County schools. Maxwell v. County Board of Education

of Davidson County, M.D. Tenn., Civ. No. 2956. A grade-a-year

desegregation plan identical to the Nashville plan was ordered,

beginning with the first four grades in January 1961. 204 F. Supp.

768 (1960), affirmed, 301 F.2d 828 (6th Cir. 1962). The Supreme

Court, however, held that the transfer provisions "promote dis

crimination and are therefore invalid." Goss v. Board of Edu-

5/cation of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683, 688 (1963).

4/ [B]ecause of residential segregation, only 115

of the 1,400 Negro students in the first grade

were eligible to attend schools previously

attended only by white students, under the zoning

system based on residence; and only 55 of the

2,000 white students in the first grade were eli

gible to attend schools previously attended only by Negro students. All 55 of the white students

were through their parents, granted transfer to

white schools, and 105 of the 115 Negro students

were, through their parents, granted transfers to Negro schools.

270 F.2d at 215.

5/ In 1963, the Nashville and Davidson County school systems

were consolidated as part of a general consolidation of the City

and County into one metropolitan government, and the Metropol

itan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County

(hereinafter "board") was substituted as defendant. R. 1.

4

In 1968, the Supreme Court decided " [t]he burden of a

school board today is to come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work, and promises realistically to work now,"

Green v. County School Board of Kent County, 391 U.S 430, 438:

see Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 369 U.S. 19

(1969). Thereafter, in November 1969, plaintiffs filed a

motion for immediate relief. R. 7, A. __. At that time,

fourteen years after the action was filed, 81% of white pupils

attended schools over 90% white, while 62% of black pupils

attended schools over 90% black. 317 F. Supp. 980, 987 n. 4.

The district court preliminarily enjoined all school con

struction and expansion, and proceeded to consider whether the

board was "properly fulfilling its affirmative duty to take all

necessary steps to facilitate the immediate conversion of the

Metropolitan Nashville Davidson County public schools to a unitary

school system in which racial discrimination will be totally

eliminated." 317 F. Supp. at 985. The court specifically found

6/

that "defendant's inaction in failing to alter [zone] lines

amounts to a constitutional violation just as certainly as if

5/ continued

In 1968, the board was found to have violated the due process rights of students at black Cameron High School in sus

pending the school from all interscholastic athletic competi

tion for a year. 293 F. Supp. 485.

6/ Most school construction and drawing of zone lines was done prior to Brown v. Board of Education with the aim of maintaining

segregation, and there were numerous examples of zones lines

drawn to perpetuate segregation in contiguous attendance zones

at the elementary, junior high and high school levels. 317 F.

Supp. at 987-989.

5

defendant itself and purposefully gerrymandered the zones to

prevent integration. 317 F. Supp. at 990. The court also found

that portable classrooms were used to maintain segregation,

that black teachers were being disproportionately assigned

to identifiable black schools, and that the board's construction

of new schools was designed to maintain segregation. 317 F.

Supp. at 989, 991-992.

The district court then proceeded to frame a remedy for

7/1971-72, after this Court vacated a stay. 436 F.2d 856 (1970).

B. The 1971 Remedial Order

During the remedial proceedings, the Supreme Court decided

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971), whose principles the district court's memorandum opinion

8/of June 28, 1971 , R. 23, A. __, expressly sought to apply.

7/ District Judge William E. Miller, who presided over the first 16 years of the litigation, was replaced by District

Judge L. Clure Morton in 1971.

8>/ The court summarized the requirements of Swann as follows:

Objective

"The objective today remains to eliminate

from public schools all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation." Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, [402 U.S. 1,

15 (1971 ). ] .

The Supreme Court has stated that "[t]he

objective is to dismantle the dual school

system," Swann, supra, at [28], "... to elim

inate invidious racial distinctions," Swann,

supra, at [18], and "... to achieve the great

est possible degree of actual desegregation,

taking into account the practicalities of the

situation. " Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners , [402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971).]

6

Three desegregation plans were considered. R. 23, pp. 2-8, A.

__. Defendant board, while accepting an "ideal racial ratio of

an integrated school as one which is 15% to 35% black" in a 25%

black system, filed a plan which left the elementary schools

significantly unchanged and six of 38 secondary schools majority

black. The court rejected the plan as not constitutionally

sufficient. Plaintiffs filed a "model" or preliminary plan

which used clustering and pairing, using both contiguous and

non-contiguous zoning, to achieve a 15% - 35% black representa

tion in almost all elementary schools, and all the secondary

schools. While observing that integration would be achieved,

the court rejected plaintiffs' plan on grounds of practicality.

8/ continued

Test

A plan "that promises realistically to

work, and promises realistically to work

now" is required. Davis, supra, at [38]

quoting Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 431 (1968). A plan "is to be judged

by its effectiveness." Swann supra, at

[26]; Davis, supra, at [38]. A plan "is not

acceptable simply because it appears to be

neutral." Swann, supra, at [28].

Methods to Accomplish Objective

The following methods have been acknowledged

by the United States Supreme Court: (1) restruc

turing of attendance zones, both contiguous and

non-contiguous; (2) restructuring of schools;

(3) transportation; (4) sectoring; (5) non-dis-

criminatory assignment of pupils; (6) majority

to minority transfer; and (7) clustering, group

ing and pairing. Swann, supra; Davis, supra.

R. 23, p. 6, A.

7

The third plan was submitted, at the request of the court, by

the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. That

plan, as amended, which the court approved, had the following

features: At the elementary level, five inner city schools would

be closed, 74 schools were projected as 16% - 41% black and 22

schools in the outer reaches of the county would not be subject

to desegregation requirements and would remain 89-100% white.

At the secondary level, 18 of 25 junior high schools were

projected as 20% - 40% black and seven junior high schools, on

the outskirts and excluded from desegregation, would remain

90-100% white. Of 18 high schools, 11 were projected as 18% -

44% black, and seven were excluded, 6 remaining virtually all

white and one 89% white. Some high schools were converted to

junior high schools and two inner city high schools closed.

Plaintiffs objected to the HEW plan as being not the most ef

fective plan possible and because it imposed a disproportionate

burden on black students, busing only black students in grades

1-4 and closing only predominantly black schools. R. 20, A. __.

The court permitted the construction of a comprehensive

high school in the northeast Joelton area in an area halfway

betwen black and white populations, but denied permission

to build a proposed northwest Goodlettsville comprehensive high

school in an all white community far from black areas. R. 23,

9/pp. 15-16, A. __-__. An application to acquire additional

9/ The court referred to Briley Parkway as "generally the divider between the inner-city pupils and outer-county pupils."

Id. The court, however, denied the request to expand another

high school, Hillsboro, although it was .6 miles from Briley

Parkway. R. 74, Vol. 1, p. 561. See infra.

8

property for Hillsboro school, in south central Nashville, to

transfer Hillsboro into a comprehensive high school was "denied

for the same reasons that the Goodlettsville school was not

approved". Id.

The court concluded with specific instructions restricting

the use of portable classrooms, expansion of schools on the

outskirts of the County excluded from desegregation requirements

and new school construction without prior court approval.

Portable classrooms, referred to generally as "port

ables," have been used by the Board to house students

in schools which were all-white or had received only

token integration when there were vacant rooms in

predominantly black schools. In effect, portables

have been used to maintain segregation. In the future, portables shall be used only to achieve

integration and the Board is hereby so enjoined.

In the plan adopted by the Court, certain

schools in the outlying areas of the school district

remain virtually all white. By reason of the past

conduct of the Board the Court hereby sets forth the

following restrictions to prevent these schools from

becoming vehicles of resegregation. It is ordered that the schools which have less than 15 per cent

black pupils after the implementation of the plan,

shall not be enlarged either by construction or by

portables, and shall not be renovated without prior

court approval. Furthermore, no additional schools

shall be erected without prior court approval.

R. 23, pp. 16-17, A. __-__. The court specifically retained

jurisdiction.

The 1971 remedial order was affirmed on appeal by this

Court. 463 F.2d 732. This Court rejected the board's objec

tions to the use of the flexible white to black population ratio

as "a guide in seeking a practical plan," and unsubstantiated

claims of adverse effects on the health and safety of students

because they were not previously presented to the lower court.

9

463 F.2d 743-746. Plaintiffs appealed because (a) plaintiffs'

plan would have achieved greater integration, and (b) the HEW

plan placed the burden of desegregation disproportionately

upon black children by requiring only younger black children in

grades 1-4 to be bused, and the closing of schools in black

areas. The Court declined to remand for further proceedings,

lest long-delayed desegregation be deferred, but noted that

adverse effects of the plan could be brought to the attention of

±0/

the district court. 463 F.2d at 746.

10/ With respect to the claim of disproportionate burden, the

Court stated:

It may be that this is a temporary expedient or it may be that there are practical reasons

to justify it for longer duration. In any

event, any adverse effects of this aspect of

the plan can, of course, likewise be brought to

the District Judge's attention when the case is

back before him.

463 F.2d at 746.

Judge McCree concurred and noted that plaintiffs could subsequently invoke the district court's retained jurisdiction

to supervise the implementation of the plan in order to obtain more effective and equitable integration. 463 F.2d at 751-752.

It is to be emphasized, nevertheless, that

our refusal to take affirmative action on this

issue at this time results only from the

peculiar timing, posture, and history of this

case. Our opinion should not be construed in any

way as a qualification of the principle that a

district court has an obligation to endeavor

to distribute the burden of integration equita

bly on all races and that any deviation from

this norm, without a compelling justification,

is impermissible.

Id.

10

The board's motion to stay the issuance of the Court's

mandate was denied, as was its subsequent petition for cer

tiorari. 409 U.S. 1001 (1972).

C . Proceedings Since the July 1971 Remedial Order

1. 1972-1978 Proceedings

On July 17, 1972, the board petitioned the district court

to end the transportation program at and resegregate three

inner city junior high schools, two as virtually all black

schools and one as virtually all-white, because of a claim of

extreme hardship on students generally, particularly young black

inner city children, resulting from transportation. R. 45, 46,

A. __-__. The petition was based on the board's experience with

the first year of implementation of the 1971 remedial order.

Plaintiffs opposed the petition on the ground that any strain on

the transportation system or hardship on students was caused by

the refusal of the board and the metropolitan government to

provide the necessary transportation facilities for implementa

tion of court ordered school desegregation. R. 47, p. 1, A.

_. Plaintiffs reiterated their assertion that the HEW plan did

not result in the greatest degree of desegregation, and that the

11/plan should be strengthened rather than weakened.

11/ Plaintiffs sought, inter alia, implementation of plain

tiffs' plan or some alternative that would "'achieve the greatest possible degree of desegregation'," the elimination of

the discriminatory features of the HEW plan providing for closure of inner city schools in black areas and for black

inner city children in the lower grades alone to be bused, and

an order directing the board to provide adequate transportation

facilities and making the major and metropolitan council

parties defendant and enjoining them from withholding necessary

funds from the board. R. 47, p. 4, A. __.

On August 17, 1972, the court found that the board had

failed to implement the desegregation plan in good faith.

1. The school board did not purchase one piece of equipment for the purpose of converting the

school system from a dual school system segre

gated by race into a unitary one.

2. By reason of the failure of the school board to purchase adequate transportation equipment, the

ordered integration plan was deficiently implemented.

3. Sufficient funds are available in the school budget of the school board for the school year 1972-1973 to

purchase the needed school buses.

4. No Constitutionally sufficient reason was ad

vanced by the school board for the resegregation of

the school system.

5. The school board has not made a good faith effort to obtain sufficient buses to implement

the court ordered integration plan.11/R. 49, p. 5, A. __. The board's failure to provide for

12/ After going through the motions of asking theCity Council for funds to purchase the needed

buses, the school board in effect said "We

have complied with the court order. We have

requested funds and the request has been denied.

We do not need to make any additional efforts.

We do not need to cut other expenditures in any

other area to insure that the full constitutional

rights of children are secured. We have rendered

lip service to the Constitution."

The Court holds that this surface compliance does not meet the minimum requirements of dismantling

a dual school system. The Court feels that a

school board which has been adjudicated three

times as violating the equal protection rights

of school children must do more. Effort and

sacrifice are not unknown to the American dream

of equality under the law.

* * *

This Court finds that the defendant school board has not made a good faith effort to com

ply with the court ordered integration plan.

R. 49, p. 4, A. __.

12

adequate transportation and petition for resegregation, were

11/found to be an attempt to frustrate desegregation. The

court directed the board to purchase 30 buses "to both alleviate

hardships present during the 1971-72 school year and to advance

the orderly and efficient establishment of a unitary school

system in Metropolitan Nashville." R. 49, p. 5, A. __. The

court added the city council and mayor as parties defendant, and

temporarily restrained them from interference with school

officials or with the implementation of the plan. No action,

however, was taken on plaintiffs' request for more effective

13/ In effect, the defendant to this cause hasendeavored to accomplish indirectly what it can

not permissibly accomplish directly— the frustra

tion of this Court's plan to establish a racially

integrated school system. Then, relying upon

the state of public unrest resulting from the

staggered bussing schedules made necessary by their refusal to provide adequate school trans

portation, the defendant petitioned this Court to retreat from the integration progress made in the

past year and to resegregate a number of schools in

order to free the twenty-nine school buses necessary

to relieve the burdensome schedule. This, by its

very terms, would be unconstitutional under Brown

and its progeny. But, this is the only solution

proposed to this Court by defendant.

R. 49, pp. 7-8, A. __-__. The court added that:

The basic thrust and end result of defendant's

actions has been to perpetuate and endorse a bussing schedule so unreasonable and harsh that not

only has the principal goal of a unitary system

been obscured by public reaction and indignity,

but also that the health, safety, and security

of the children involved have been compromised

by their exposure to risks and dangers.

R. 49, pp. 9-10, A. __-__.

13

equitable relief.

Thereafter, the board reported to the court that it had

14/

complied with the order by purchasing 35 and renting 15 buses.

15/R. 55.

During these proceedings, and thereafter, the district

court took no action on requests of the board, opposed by

plaintiffs, to make various changes in the desegregation

16/plan. On May 30, 1973, the board petitioned the court

to approve an extensive secondary and elementary school con

struction program for 1 973-79. R. 60, A. __. Plaintiffs

14/ The Mayor responded with a recusal motion. While noting that the affidavit was "legally insufficient" and "nothing more

than a subterfuge", Judge Morton nevertheless recused himself.

R. 51. Upon Judge Morton's recusal, Chief Judge Frank Gray, Jr

took over the case.

15/ The court sustained the propriety of a temporary restraining order enjoining the added defendants from interference with

board members and staff from seeking and obtaining further

buses when originally issued, but vacated the order as unneces

sary in light of the board's report that it had obtained

buses.

Thereafter three newly added black City Council member

defendants filed a third party action against the Secretary of

HEW, other HEW officials and the United States for withholding

federal funds for transportation expenses to implement the

court-ordered desegregation plan. The school board joined as a

third party plaintiff. The court held it has jurisdiction over

the federal official defendants, 372 F. Supp. 528, and then held that the federal officials acted illegally and unconstitu

tionally in refusing to release emergency school assistance funds for busing for desegregation purposes, and enjoined them

from enforcing such an illegal and unconstitutional transporta

tion policy with respect to assistance requests of the school

board. 372 F. Supp. 540.

16/ On March 17, 1972, the board proposed an attendance zone and site for the comprehensive high school (Whites Creek)

in the Joelton area. The school was built without prior obtain

ing approval. 492 F. Supp. 172, 173.

14

»

responded with a motion for specified information that would

permit plaintiffs to properly review the petition and to prepare

objections on the ground that "school construction and expansion

... apparently would increase racial segregation in the schools,

further decimate schools in black neighborhoods and place an

unfair burden on black children in school desegregation." R.

11/60A, A. __. On May 31, 1973, the board petitioned the

court to add portable classrooms to elementary schools as part

of a kindergarten program. Plaintiffs answered that the peti

tion should be denied because the use of portables would "per

petuate and increase segregation rather than achieve integration"

by, inter alia, increasing the capacity of 16 of the 22 virtually

all-white elementary schools left segregated by the desegregation

plan in violation of the 1971 remedial order, while inner city

schools were underutilized. R. 60B, A. __. The court took no

action on the petitions, and the board went ahead with placement

of the portables beginning in the 1973-74 school year. The

board, through counsel, so informed the court, and subsequently

informed the court of other board actions taken with respect to

school construction program without court approval. See 492

F. Supp. at 174, n.19.

Thereafter, on July 17, 1976, the board reported that it

would expand Cole Elementary School, one of the 22 schools left

segregated, by relocating the fifth and sixth grades to an

"annex" at the Turner Elementary School. I_d. On October, 14,

1976, the board filed a motion to amend its petition of May 30,

17/ The motion was neither responded to by the board nor acted upon by the court.

15

1973 and for approval of the proposed construction of Good-

lettsville-Madison High School. Ijd. Plaintiffs responded with a

verified petition for contempt and for further relief. R. 68,

18/

11/The district court took no action on the 1976 submissions.

On July 24, 1978, as amended on August 18, 1978, the board

18/ Plaintiffs' petition stated, inter alia, that the addition

of the "annex" expanded Cole Elementary School in violation

of the 1971 remedial order, and that the board had publicly

announced a plan to build the Goodlettsville-Madison and expand

Hillsboro high schools as part of a plan to expand or construct

comprehensive high schools in predominantly white suburban areas, while projecting the closure of Pearl High School and

several elementary schools in the inner city, predominantly

black areas in violation of the 1971 remedial order. R. 68, p.

4, A. __. Plaintiffs' petition averred that these proposals;

(a) place [d] a greater burden on accomplishing

integration on black students and their parents

than on white students and their parents;

(b) constitute [d] continuing discrimination against

black citizens, school children and neighborhoods by

proposing to close Pearl High School and other schools

located in or near black neighborhoods solely be

cause of their history as black educational insti

tutions and requiring black children to travel

invariably to white neighborhoods to receive an

education with no reciprocal requirements upon

white children;

(c) discriminate[d] against and stigmatize[d] black

parents, school children and neighborhoods by placing

all of the new Comprehensive High Schools in all or

predominantly white neighborhoods rather than in

areas accessible to both white and black residential

neighborhoods as contemplated by the Court's afore

said 1971 opinion and order.

19/ Plaintiffs filed interrogatories on June 4, 1977 requesting information about physical condition, student capacity, capital

expenditures, desegregation efforts, and changes in the 1971 deseg

regation plan. A motion to compel was subsequently filed, and the

board sought an extension. The court took no action and no answers were filed by the board until 1978.

16

filed a petition for approval of school attendance zones for 1978-

20/

1979. Plaintiffs responded that the petition should be

denied, and filed a separate amendment to the 1976 petition for

21contempt and for further relief. S.R. , , A.

20/ With respect to secondary schools, the board stated that it

had completed construction, expansion and other preparation for the

opening of comprehensive high schools listed in its May 30, 1973

petition, including inter alia, the opening of Whites Creek and

the closing of former black North High School; the addition of

ninth grade to all high schools; the decision of the board to

develop or seek comprehensive high school in an unindentified

inner city site; permitting students at non-comprehensive high

schools, including Pearl High School, to transfer to a compre

hensive high school; restructuring of junior high schools; and

the closing of six inner city schools as junior high schools.

With respect to elementary schools, the board stated it intended

to close or use for other purposes several inner city schools,

and former junior high schools as elementary schools.

21/ Plaintiffs stated, inter alia, that:

[Defendants now claim to have constructed many or most

of the said expansions to formerly white schools, and are

asking the Court to approve zone changes therefore, while

at the same time seeking Court approval of the closure

of most of the elementary and secondary schools located

in the inner city areas (Bailey, Carter-Lawrence,

Johnson, and Murrell Elementary Schools, Washington

Junior High School and North High School) and downgrading

most of the other inner city black schools (Rose Park

from junior high to grades 5-6; Cameron, previously

reduced from high school to junior high school, now

reduced from junior high school to combination ele

mentary-junior high, grades 5-8; Wharton from junior

high to elementary grades 5-6; Cumberland from junior

high to elementary grades 4-6, leaving only two formerly

black secondary schools in the entire county, namely:

Meigs Junior High School, grades 7-8, and Pearl High

School, grades 9-12.

With respect to Pearl High school, plaintiffs stated that:

On information and belief, defendants had proposed and

were insisting on closing Pearl High School also, and

were prevented from doing so only by virtue of exten

sive, extended and strenuous protests by black citizens

and groups and accompanying protests by white citizens and groups similarly objecting to a proposed closing of

17

No immediate action was taken by the court, and the board went

ahead and instituted its proposed changes in the 1978-79 school

year.

2. 1979-1981 Proceedings

In the spring of 1979, the district court, held a pre

trial conference on all pending matters, and stated that it would

consider, in successive phases, (1) the 1973 and 1978 petitions

of the board, (2) staff and faculty issues raised by plaintiffs,

plaintiffs' contempt petitions and (4) plaintiffs' request for

23/attorneys fees. To date, the court has heard and decided

only the first phase.

(3)

21/ continued

Cohn High School, another inner city high school, which

although predominantly white, is near the black neigh

borhood in northwest Nashville. Even so, the plan of

zoning for high schools in 1978-1979 now proposed by

defendants for approval by the Court is discriminatory

by providing an open zone option as to said two inner

city high schools, Cohn and Pearl, and an adjoining pre

dominantly white neighborhood high school in the north

eastern areas of the county (Joelton). The almost in

evitable effect of the open option is to lessen the

likelihood of a stable school population in Pearl High

School...

S. R. , p• 1, A# .

22/ Upon Chief Judge Gray's death, the case was assigned in August, T978 to District Judge Thomas A. Wiseman, Jr., who continues

to hear the case. 492 F. Supp. 167.

23/ Plaintiffs filed motions for attorneys fees and costs on

February 8, 1974 and April 11, 1975, as well as motion to dis

pose of the motions on October 16, 1975. R. 63, 66, A. __, __.

In addition, all of plaintiffs' submissions since entry of the

1971 remedial order have included requests for award of attorneys fees and costs.

18

After hearings in June and July, 1979, the court issued a

memorandum opinion on August 27, 1979, 479 F. Supp. 120, 122-123.

From the proof adduced on Phase 1 of the

hearing, the Court finds the following:

1. The perimeter line drawn by the Court in 1971, by which no requirement of

either transportation or attempts at racial

balance, was mandated outside the perimeter, has encouraged white flight to the suburbs,

and to those school zones unaffected by the

1971 order. The combined effect of the order

and the flight therefrom, either to suburban

public schools or to private schools, has

been:

a) that inner city schools have be

come progressively resegregated;

b) that the projected ideal ratio of 15 percent to 35 percent black population

in each school has become increasingly more

difficult to meet;

c) that the school facilities out

side the Court-ordered perimeter have

become increasingly inadequate to accommo

date the growing student bodies.

2. The resegregation, resulting, at

least in part, from the nonetheless good

faith efforts of the School Board in the

implementation of the Court's order, amounts

to a de jure segregation.

5/ The most dramatic example of such resegregation can be seen in enrollment statistics

for Pearl High School for the school years 1970-71 through the projections for 1979-80.

While the court did not specify implementation actions of the

board which caused de_ jure segregation, the uncontradicted

record shows that: The board attempted to mount an extensive

construction program in predominantly white areas at a time

the system was contracting, although there was overcapacity

in predominantly black inner city schools and schools in

19

in black areas were being closed. A ring of comprehensive

high schools was developed and built in suburban white areas

without prior court approval, while inner city high schools were

not developed and high schools in black areas closed (North) or

25/threatened with closing (Pearl). The board expanded the

capacity of virtually all white schools on the outskirts of the

County through the placement of portable classrooms, additions

26/and annexes in violation of the 1971 remedial order. While

expanding facilities in predominantly white suburban areas, the

board closed schools in predominantly black inner city areas,

requiring black students to bear an even greater burden of trans-

27/

portation to schools in white suburban areas. The board

made no efforts to achieve greater levels of desegregation at

inner city schools by assigning students from white suburban

schools or to relieve the disproportionate burden of transporta-

28/

tion on younger black students. No efforts were made to

relieve overcrowding in white schools by assigning white students

24/

24/ See, e.g. , R. 74, Vol. II, pp. 896-898 , 933-936 , 961-962,M4, TU27-T0T3; Vol. Ill, pp. 27-32 ; R. 76, Exh. 3.

25/ See, e.g. , R. 74, Vol. II, p. 876-877, 957-959.

26/ See, e.g. , R. 74, Vol. I, pp. 162-165, 170-172, 200A-205;Vol. II, 899-901 , 930-931, 970-974.

27/ See, e.g., R. 74, Vol. I, pp. 174-177, Vol. II, 741-743,752, 873-848; R. 76, Exh. 79.

28/ See, e.g., R. 74, Vol. I, p. 129, Vol. II, pp. 853, 890- 894, 1027-1033.

20

to underutilized inner city schools.

During the July hearings, the court had orally enjoined

the board's 1978 policy of permitting resegregative automatic

options out of Pearl because: "[I]t became evident to the Court

that this provision has been utilized extensively by white

students assigned to Pearl to escape such assignment. ...

The effect of this policy upon the already-established trend

toward resegregation at Pearl was disastrous." 479 F. Supp. at

124. The court directed the board to take immediate action because

of "the urgency of the situation," ĵ d. , but the board responded

with a policy of subject matter program transfers whose opera

tion, the court later found, had "a negative impact upon the

desegregation efforts of the School Board." 479 F. Supp. at

129. However, most of the transfers were left in effect for

1979-80 and senior students permitted to continue to exercise an

automatic option out of Pearl. Id.

The board prepared and filed a proposed desegregation plan

in February 1980, and further hearings were held. On May 20,

1980, the court issued a memorandum opinion which rejected the

proposed plan. 492 F. Supp. 167. The board's 1980 plan in

cluded: (a) use of a racial ratio of 32% present black system-

wide student composition with a variation of - 20%; (b) retention

of its comprehensive high schools with either the phasing out of

29/

29/ Id.

21

Pearl High School or its replacement with a new Pearl-Cohn inner

city comprehensive high school, and approval of construction of

the northwest Goodlettsville-Madison Comprehensive High School;

(c) noncontiguous zoning of inner city students to five predomi

nantly white suburban junior high schools and noncontiguous

zoning of students from white schools to inner city Cameron

middle school complex; (d) continued placement of 1-4 grade

schools in predominantly white suburban areas and placement of

5-6 schools in inner city areas, requiring continued dispropor

tionate burden of busing of younger black children. 492 F. Supp.

at 178-183.

The court rejected the 1980 plan because student transporta

tion imposed a disparate burden on achieving desegregation on young

black children, and closed four relatively small high schools in

the outer fringes of the County, which, inter alia, "have posed

a problem to the Board ... in its efforts to achieve a desegre

gated system." 492 F. Supp. at 191, 194. However, the court

also rejected the plan because of concerns about the "lack of

realistic promise of achievement" in light of white flight and

certain "social, educational and economic costs of student

transportation for desegregation. The court set forth "guide

lines and specific directives" requiring inter alia (a) a three

tier grade structure of K4-4-4 or some variation, (b) "K-4

( or variation) of a neighborhood character," (c) middle schools

with a minimum presence of at least 15% of either race in the

minority, (d) a high school plan, and (e) the use of magnet

schools.

22

The board filed a plan on January 19, 1981. S.R. ,

30/

A. __. On February 6, 1981, plaintiffs filed their objec-

31/

tions. S.R. __, A. __. Plaintiffs subsequently submitted

supplemental objections with an alternative K-4 and middle

school "conceptual" assignment plan, which was based on the

board's plan, but clustered and paired, and changed the feeder

patterns in order to achieve greater desegregation and dis

tribute the burden of transportation more fairly. S.R. _,

A.__.

A hearing was held and the district court struck plain

tiffs' alternative plan as inconsistent with its May 20, 1980

order. S.R. __, A. __. The middle school portion of the

alternative plan was subsequently admitted in evidence, but the

K-4 part was admitted only for identification because it diverged

from the lower court's findings for neighborhood schools at that

level. S.R. __, transcript of March 30, 1981, pp. 283-284, 287.

The parties submitted their proposed findings of fact, and, the

day after, the district court adopted the board's entire 27 page

30/ The plan is described infra at pp. 24-30.

31/ Plaintiffs objected because, inter alia (a) "the plan provide[d] for massive resegregation of black and white children

in grades K-4" with 47 of 75 schools over 90% one race, and (b)

"the plan for Middle Schools (grades 5-8) continues to place

a disparate burden of transportation upon black school children

in that said Plan apparently proposes one way busing at pre

dominantly black elementary school children for inner city areas

to 11 middle schools in predominantly white residential areas

... by way of non-contiguous zoning in each instance, while

transporting white children to the inner city in only one

instance" through a contiguous zone.

23

proposed memorandum approving the plan filed by the board.

A timely notice of appeal was filed May 15th. On August

19th, this Court stayed implementation of the district court's

1980 and 1981 orders, and expedited the appeal. Motions to

vacate the stay have been denied by the Supreme Court.

D. The Board's 1981 Plan

The board's plan filed pursuant to the district court's May

20, 1980 order and approved by the court on April 17, 1981 is

briefly summarized.

Elementary Schools

The plan stated that, "[i]n developing the elementary school

proposal for submission of the Board of Education, the committee

began by looking at the neighborhood character of schools as

mandated by the court, all the while serving to maximize

the opportunities for integration in a neighborhood configura

tion. " The plan then proposed 75 such K-4 elementary schools

33/with the following projected enrollment and racial composition.

32/

32/ The title of the board's proposed findings was changed to

"Memorandum" and the last paragraph changed to state the order

was a final appealable order and that no stay would be granted.

33/ The plan stated that 31 of the 75 elementary schools were projected to be walk-in schools. The plan also stated that "ap

proval of this plan may require construction and expansion in

areas where instruction was heretofore prohibited," referring

to construction and expansion of facilities at suburban schools

which the 1971 remedial order excluded from desegregation requirements and prohibited from expansion without prior court

approval.

24

Elementary Schools Projected

Enrollment % White % Black

Allen 219 96.8 3.2Amqui 371 99.0 1.0Bellshire 165 90.3 9. 7Berry 235 97.0 3.0Binkley 486 90.5 9. 5Bordeaux 386 23.6 76.4Brink Church 418 21.3 78.7Brookmeade 386 96.4 3.6Buena Vista 437 12.8 87.2Caldwell 496 6.9 93. 1Carter-Lawrence 571 2.8 97.2Chadwell 202 96.0 4.0Charlotte Park 321 94. 1 5.9Cole 960 93.0 7.0Cotton 273 50.6 49.4Dalewood 332 96. 1 3.9Dodson 640 95.6 4.4DuPont 395 89.6 10.4Eakin 222 88.3 11.7Early 351 4.6 95.4Fall-Hamilton 292 59.6 40.4Gateway 223 100.0 0.0Glencliff 419 97.4 2.6Glendale 330 28.6 71.5Glengarry 307 98.4 1.6Glenn 266 32.0 68.0Glenview 386 85.5 14.5Goodlettsville 295 97.8 2.2Gower 303 93. 1 6.9Gra-Mar 324 79.0 21.0Granberry 358 95.0 5.0Julia Green 263 99.0 1.0Harpeth Valley 345 98.6 1.4Haynes 336 9.8 90.2Haywood 381 93.4 7.6Head 581 33.1 96.9Hermitage 406 97.7 2.3Hickman 328 100.0 0.0Cora Howe 981 61.7 38.3Inglewood 394 34.8 65.2Jackson 379 92.8 7.2Joelton 224 100.0 0.0Johnson 378 19.3 80.7Joy 488 64.3 35.7King's Lane 633 4. 1 95.9Kirkpatrick 253 58.5 41.5Lakeview 738 94.8 5.2Lockeland 301 97.0 3.0

25

McGavock 304 98.7 1.3McKissack 538 6. 5 93.5Dan Mills 217 94.7 5.3Morny 190 81. 1 18.9Napier 394 15. 7 84.3Nelley's Bend 359 91.5 8.5Old Center 167 96.4 3.6Paragon Mills 370 89. 7 10.3Park Avenue 224 57. 6 42.4Percy Priest 172 97.7 2.3Richland 341 96.5 3.5Rosebank 287 87.9 12. 1Ross 178 79.8 20.2Shwab 328 83.2 16.8Stanford 369 98.6 1.4Stokes 331 37.2 62.8Stratton 447 92.8 7.2Sylvan Park 153 100.0 0.0Tusculum 424 92.7 7.3Una 497 94.6 5.4Union Hill 106 100.0 0.0Wade-Jordonia 282 54.0 46.0Warner 671 25.0 75.0Westemeade 387 95.6 4.4Wharton 334 1.0 99.0Whitsitt 317 88.6 11.4

S.R. __, A. __. The board's plan would result in substantial

racial isolation. Fully 47 of the 75 schools were projected as

more than 90% one-race. 39 schools would be 90% white and 8

schools over 90% black. 14 schools were projected as more

than 3/4 black. I_d. Of the eight schools scheduled to be over

90% black, six were also over 90% black in 1970-1971 before the

1971 remedial plan went into effect. (The exceptions are Cald

well, which was 89.9% black in 1970, and Hayes which was 83.1%.

R. 76, Exh. 3.) The extent of racial isolation under the

34/board's plan is greater than that under the 1971 remedial order

34/ In 1978-79, only 19 of 68 elementary schools with grades 1-4

were over 90% white in racial composition, and none were over

90% black. R. 76, Exh. 3. 19 of the 22 elementary schools

26

or the alternative plan proposed by plaintiffs.

The plan proposed an intercultural exchange program "for

the provision of inter-cultural experiences on a periodic basis

to children in grades K-4 in those schools in which the minority

representation is less than 15% black or white." The plan also

included a K-4 "intervention-remediation" program in response to

the district court's order that the board provide "remediation

efforts in those schools, or classes within schools, made up

largely of socio-economically deprived children who suffer the

continuing effects of prior discrimination." 492 F. Supp. at

1 96.

Middle Schools

The board's plan for middle schools called for 24 middle

schools for grades 5 - 8 located in junior high or former

senior high school buildings, including Pearl High School.

Seven schools were projected to be majority black and 17 schools

35/

23/ continued

excluded from the desegregation requirements of the 1971 remedial order with any grade 1-4 students were over 90% white. None of

the 46 elementary schools in the area affected by the desegregation requirements of the 1971 remedial order with any grade

1-4 students were at least 90% either race.

35/ Under plaintiffs' proposal ten of 75 schools were over 90%white and none were over 90% black. S.R. __, A. __. Plaintiffs'

conceptual model was based on the board's plan for the construc

tion of its proposal, but regrouped students to realize a

greater level of desegregation. Pairs or clusters with K-2 and K, 3-4 schools were devised in which schools the two kinds of

grade configurations were located in both inner city and

outer areas. Students in five schools which fell within 20.2 -

42.4 range, and 10 virtually white schools in outlying parts of

Davidson County were left as is.

- 27

majority white under the plan when fully in effect. 20 of

the 24 schools were projected to fall within the district court's

15% minimum either race presence standard. Noncontiguous zones

were established which assigned students from predominantly

black inner city areas to 11 middle schools located in predomi

nantly white residential areas. S.R. __, Exh. 269. These

assignments required bus transportation. No students from

predominantly white areas were assigned to middle schools

37/located in predominantly black areas by noncontiguous zones.

36/ The projected enrollment and racial composition of the middle schools were as follows:

Middle Schools ProjectedEnrollment % White % Black

Joelton 777 60.5 39.5Goodlettsville 766 79.9 20. 1DuPont (Jr.) 560 80.4 19.6Nelly's Bend 682 82.8 17.2Ewing Park 644 29.2 70.8Cumberland 469 39.2 60.8Highland Heights 652 40.8 59.2Meigs 790 20.5 79.5East 902 75.2 29.8Litton 1026 72.7 27.3DuPont (Sr.) 848 81.9 18.6Donaldson 896 85.2 14.8Two Rivers 1004 82.2 17.8Cameron 901 82.9 17. 1Rose Park 567 23.3 76.7Wright 834 88.3 11.7Apollo 757 85.9 14. 1Antioch 1182 96.0 14.0McMurray 974 79.0 21.0Moore 683 80. 1 19.9Pearl 914 22.6 77.4Cohn 815 49.0 51.0Bass 887 65.5 34.5Bellevue 797 84.7 15.3

S.R. _f p. __f A• .

37/ Plaintiffs proposed an alternative middle school assignment pattern which resulted in 22 majority white schools and two

28

High Schools

The plan proposed ten comprehensive high schools, including

a new inner-city school, Pearl-Cohn, and a new Goodlettsville-

Madison high school to be operational by 1984-85. Pearl-Cohen

school was to be located at the site of the Ford-Greene Elemen

tary in the zone served by the present Pearl and Cohn high

schools. Three high schools were projected to be majority

38/black and seven were projected to be majority white. All

of the comprehensive high schools were projected to fall within

the district court's 15 either race minimum. While the board

initially recommended that space was unavailable for a magnet

school serving grade 7-12 for academically talented students in

1981-82, the board subsequently stated tht the present West End

High School could immediately be opened as an academic high school.

37/ continued

majority black schools (Ewing Park (68.1%) and Pearl (55.5%), and students from predominantly white outer areas were assigned

to schools located in inner city areas as well as students from

predominantly black inner city area being assigned to schools

located in outer areas.

38/ The projected enrollment and racial composition of the ten comprehensive high schools in 1984 follows:

ProjectedHigh Schools Enrollment % White % Black

Whites Creek 2100 43.7 54.6Goodlettsvilie-Madison 1818 85.1 14.9Maplewood 1410 40.8 59.2Stratford 1535 58.4 31.6McGavock 2765 84.9 15. 1Glencliff 1921 78.8 21.2Overton 1748 82.9 17. 1Hillsboro 1015 72.3 27.7Hillwood 1274 69.3 30.7Pearl-Cohn 1553 42.3 57.7

S.R. __, p. __, A.

29

Other Features

The board's plan provided for a multicultural program

designed to involve children in all schools in grades K-12, and

a black history elective in secondary schools. S.R. __, p. __,

A. __. While the Board recommended that the plan be immediately

implemented on an interim basis in the area encompassed in the

northwest sector, the district court directed that interim

implementation occur in the both northwest and southwest sec-

39/

tors.

In the April 1981 memorandum approving the plan, the court

decided that the 1971 remedial order's restrictive require

ment of prior court approval of zone, construction and expansion

changes, including expansion of segregated schools in suburban

areas excluded from the 1971 plan, were "obsolete or no longer

necessary". S.R. __, p. __, A. __.

ARGUMENT

This litigation spans a quarter of a century. In 1970, this

Court found that "the instant case [was] growing hoary with age,"

436 F.2d 856, 858. Not only had substantial rel ief never been

granted, but the school board was found to have maintained and

perpetuated segregation since the filing of the action through

zoning, facility, construction and faculty assignment policies.

39/ Pending the completion of Pearl-Cohn Comprehensive High School in 1984, high school students from virtually all black

Pearl and from Cohn were to be assigned to Hillsboro and

Hillwood for the interim period. S.R. __, p. __, A. __.

30

463 F.2d at 743. It was not until the district court's 1971

remedial order and its affirmance by this Court in the wake of

the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1972), that "the

first comprehensive and potentially effective desegregation order

[was] ever entered in this litigation." 463 F.2d 732, 735.

The promise of that desegregation order, however, was never

fully realized. In 1972, the district court ordered the purchase

of school buses after finding that the board had failed to im

plement in good faith the student transportation component in

the plan's first year. But, from 1973 to 1979, the court com

pletely failed to supervise the desegregation process. In that

time, the board not only did not maximize desegregation,

but engaged in a series of activities which ultimately led to

a finding of "de jure segregation" in implementation of the 1971

plan.

Having made those findings, the court was bound by Swann and

other authority, to correct the deficiencies in the board's im

plementation of the 1971 remedial order and to assure more ef

fective and equitable desegregation. Instead, the court gutted

the 1971 remedial order for elementary schools and resegregated

grades K-4, imposed as a desegregation standard the presence

of 15% of either race, maintained substantial one-way busing of

black students, and sanctioned the closing of Pearl High School,

the historic black high school, as a senior high school. To

compensate, the plan provided various educational remediation

and other programs for students in segregated schools. The 1981

desegregation plan, in short, is less effective than the 1971

plan that defendant board had failed to properly implement.

Such a remedial order flies in the face of Swann and

this Court's 1972 opinion. The district court candidly recognized

that it was calling for "a complete reexamination of the remedy

fashioned in 1971," 479 F. Supp. 120, 123 but was of the view

that that was permissible to do so because Swann was no longer

good law: the court believed that what constituted achievement

of a unitary school system had changed "from a mere destruction

of barriers, to pupil assignment, to remediation and quality

education." 492 F. Supp. at 188, see 187-188. It was that

fundamental error that led the court to call for and approve the

board's 1981 plan.

I.

The Duty of Defendant School Board and the

District Court Was "'To Come Forward With a

Plan That Promises Realistically to Work ...

Now ... Until It Is Clear That State-Imposed

Segregation Has Been Completely Removed.'" 40/

In 1972, this Court recognized that the controlling legal

principle which governs "the question of appropriate remedial

measures to eliminate state imposed segregation is that "[t]he

objective today remains to eliminate from the public schools

all vestiges of state-imposed segregation." 463 F.2d at 740,

40/ Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 13, quoting Green v. County Board of Education,

391 U.S. 431, 439 (1968)(emphasis in original).

32

quoting Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

supra, 402 U.S. at 15. This Court clearly stated the nature

of "the duty of the District Court on default of the school

board [is] to require production of ... a plan [for a unitary

school system]" in this case.

Chief Justice Burger put the matter thus in the Davis case:

Having once found a violation, the district judge or school authorities should

make every effort to achieve the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation,

taking into account the practicalities of

the situation. Davis v. School Commis

sioners of Mobile County ... 402 U.S. [33],

37 [(1968)].

Perhaps the primary thing that the Swann

case decided was that in devising plans to

terminate such residual effects, it is appro

priate for the school system and the District

Judge to take note of the proportion of white

and black students within the area 2/ and to

seek as practical a plan as may be for ending

white schools and black schools and subsi

sting therefor schools which are represen

tative of the area in which the students live.

2/The area referred to in this case is all of

Davidson County, incuding the City of Nash

ville, which is included in the jurisdiction

of defendant Metropolitan Board of Education.

41/463 F.2d at 744.

The district court was wrong that the requirements of Swann,

and other authority have somehow lapsed over the last decade.

41/ In contrast, the lower court believed that "Swann may have

been mis interpreted to state a requirement of racial ratios in

all schools unless the Board could carry the heavy burden of prov

ing the rationale of the exception." 492 F. Supp. at 188

(emphasis added).

33

During the pendency of remedial proceedings below, the Supreme

Court reiterated the principle of Swann and Green that a "[school]

board's continuing obligation was '"to come forward with a plan

that promises realistically to work ... now .. until it is clear

that state-imposed segregation has been completely removed"'

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1,

13 (1971), quoting Green, supra at 439 (emphasis in original)."

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459 (1979),

affirming, 583 F.2d 878 (6th Cir. 1978); Dayton Board of Educa

tion v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 538 (1979), affirming, 583 F.2d

243 (6th Cir. 1978). The Supreme Court affirmed, in Penick,

that "[t]he Board's continuing 'affirmative duty to disestablish

the dual school system' [is] beyond question." 443 U.S. at 460.

Where a racially discriminatory school system has been found to exist, Brown II imposes the

duty on local school boards to "effectuate a

transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school

system." 349 US [294] 301. "Brown II was a call

for the dismantling of well-entrenched dual systems," and school boards operating such systems

were "clearly charged with the affirmative duty to

take whatever steps might be necessary to convert

to a unitary system in which racial discrimination

would be eliminated root and branch." Green v.

County School Board, 391 US 430, 437-438. Each

instance of a failure or refusal to fulfill this

affirmative duty continues the violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Dayton I, 433 US, at 413—

414; Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407

US 451, 460 (1972); United States v. Scotland

Neck Board of Education, 407 US 484, (1972)

(creation of a new school district in a city that

had operated a dual school system but was not

yet the subject of court-ordered desegregation).

443 U.S. at 458 (emphasis added). The duty of a school board

to provide effective nondiscrimintory relief was once again

recognized. As the Court put it in the Brinkman opinion,

34

Part of the affirmative duty imposed by our

cases, as we decided in Wright v. Council of City

of Emporia, 407 US 451 (1972), is the obliga

tion not to take any action that would impede the

process of disestablishing the dual system and its

effects. See also United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education, 407 US 484 (1972). The

Dayton Board, however, had engaged in many post-

Brown I actions that had the effect of increasing

or perpetuating segregation. The District Court

ignored this compounding of the original constitu

tional breach on the ground that there was no direct

evidence of continued discriminatory purpose. But

the measure of the post-Brown I conduct of a school

board under an unsatisfied duty to liquidate a dual

system is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of

the actions in decreasing or increasing the segrega

tion caused by the dual system. Wright, supra, at

460, 462; Davis v. School Comm'rs of Mobile County,

402 US 229, 243 (1976). As was clearly established

in Keyes and Swann, the Board had to do more than

abandon its prior discriminatory purpose. 413 US,

at 200-201, n. 11; 402 US, at 28. The Board has

had an affirmative responsibility to see that pupil

assignment policies and school construction and

abandonment practices "are not used and do not

serve to perpetuate or re-establish the dual school

system," Columbus, ante, at 460, and the Board

has a "'heavy burden'" of showing that actions

that increased or continued the effects of the

dual system serve important and legitimate ends.

Wright, supra, at 467, quoting Green v. County

School Board, 391 US 430, 439 (1968).

433 U.S. at 538 (emphasis added).

In framing relief, therefore, the district court wrongly

ignored the requirements of Swann and this Court's 1972 opinion,

and their reiteration in Brinkman and Penick. (Indeed, Brinkman

or Penick were neither cited nor referred to by the lower court.)

This remedial duty, of course, is no less in a case where,

as here, prior relief has been ordered but not effectively im

plemented. The duty of a district court is "to retain juris

diction until it is clear that disestablishment [of the dual

system] has been achieved." Raney v. Board of Education, 391

35

U.S. 443, 449 (1968). 42/

The District Court's Remedial Order Perpetuated or Reestablished a Dual School

System in Violation of the Constitution.

A. The Order Resegregated K-4 Elementary Schools.

The desegregation plan approved by the lower court on its

face resegregates almost two-thirds of Nashville-Davidson County

elementary schools. The plan provides that fully 47 of 75 K-4

schools will operate as single race schools, over 90% white or

black in racial composition; 39 schools would be at least

90% white and 8 historic predominantly black schools would be at

least 90% black. See supra at p.26. The district court, therefore,

II.

42/ As Penick recognized:

The Green case itself was decided 13 years

after Brown II. The core of the holding was

that the school board involved had not done

enough to eradicate the lingering consequences

of the dual school system that it had been

operating at the time Brown was decided. ...

... In Swann, it should be recalled, an

initial desegregation plan had been entered in

1965 and had been affirmed on appeal. But the

case was reopened, and in 1969 the school board

was required to come forth with a more effective

plan. The judgment adopting the ultimate plan was

affirmed here in 1971, 16 years after Brown II.

See, e.g., Anderson v. Dougherty County Board of Education,

609 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1080); United States v. Board of Education of Valdosta, 576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S

1007 (1978); United States v. DeSoto Parish School Bd., 574 F.2d

804 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 982 (1978); United States

v^_South Park Ind. School dist., 566 F.2d 1221 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 439 U.S 1007 (1978).

36

formally reestablished, in substantial terms, the dual elementary

school system which the 1971 remedial order expressly sought to

43/

eliminate.

The law of the Circuit is that a desegregation plan, which

excludes even first grade students, absent compelling need, is

contrary to the constitutional mandate that all vestiges of

state-imposed segregation should be eliminated.

Although a federal district court has broad discretionary authority in exercising its

equitable powers in formulating a remedy for violation of constitutional rights in a school

desegregation case, certainly a district court

would be abusing its authority by not ordering

any remedy at all. Nor may a district court

order a remedy of limited scope which leaves

many who have suffered violations of their con

stitutional rights without redress. To exempt

first grade students from busing would leave

vestiges of segregation intact contrary to

this Court's mandate.

Haycraft v. Board of Education, 585 F.2d 803, 805 (6th Cir.

44/1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979). Students in

lower elementary grades "'are part of the normal curriculum of

the district and entitled to a full and equal integrated edu

cation. '" 585 F.2d at 806, quoting Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d

43/ Plaintiffs believe that the educational programs included in the board's plan, i♦e., remediation, intercultural exchange, are

worthwhile. See Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S 267 (1977). Such

programs are a useful and necessary adjunct to student assignment remedies, but do not, in and of themselves, discharge the con

stitutional duty of school boards and courts to devise remedies

that will result in substantial actual desegregation.

44/ Judge Peck's opinion for the Court applied equitable

principles of Swann and other cases, including the Circuit opinions in Penick and Brinkman. Id.

37

865, 869 (5th Cir. 1972). The rule is that elementary students

must be included in desegregation remedies, including student

assignment and transportation, in order that such remedies pass

45/constitutional muster.

Indeed, in Brown v. Board of Education, supra, 347 U.S. at

484 n. 1, the only issue was desegregation of inherently unequal

separate schools in the elementary grades in Topeka, Kansas.

Sanctioning the exemption of the lower elementary grades from

desegregation thus would largely nullify Brown itself. Exemption

of grades 1-4, in any event, would be anomalous in the instant

case where the board's initial desegregation efforts in 1957

began with the first grade, and one of the principal reasons

for rejection of the board's proposed plan in 1971 was its

failure to desegregate elementary grades.

There simply is no proper issue that "the time or dis

tance of travel is so great as to either risk the health of

45/ See, e.q., Supreme Court cases: Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S 483, 484 n. 1 (1954); 349 U.S. 294, 300-301 (1955);

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, supra 402 U.S. at 36-38;

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, 402

U.S. at 10-11; Court of Appeals cases: Adams v. United States,

620 F.2d 1277, 1292-1295 & n. 24 (8th Cir. 1980) (en banc); Morgan

v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401, 410 (1st Cir. 1976); Keyes v. School

District No 1, 521 F.2d 465, 477-479 (10th Cir. 1975); United

States v. Texas Education Agency, 532 F.2d 380, 393 (5th Cir.),

(en banc), remanded on other grounds, 429 U.S. 990 (1976),

cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979); Evans v. Buchanan, 555 F.2d

373 (3d Cir. 1977), aff 'g, 416 F. Supp. 328, 348 (D. Del. 1 976);

Mills v. Polk County Board of Public Inst., 575 F.2d 1146 (5th

Cir. 1978); Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District, 495

F.2d 499, 505-506 (5th Cir.) (and cases cited), 496 F.2d 1309

(1974) (rehearing). See also, United States v. State of Texas,

498 F. Supp. 1356, 1374 (E.D. Tex. 1980); McPherson v. School

District No. 186, 426 F. Supp. 173, 183, 187-188 (S.D. 111.

1976).

38

the children or significantly impinge on the educational

process. " Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

supra, 402 U.S. at 30-31. The board's effort to argue the

same point to this Court in 1972 was referred to the dis

trict court, 463 F.2d 744-745, which rejected the claim

because " [t]he school board has not made a good faith effort

to obtain sufficient buses to implement the court ordered

integration." It was found that the board itself was

responsible for exposing students, predominantly young black

inner city students, to unreasonable risk: "The basic thrust and

end result of defendant's actions has been to perpetuate and

endorse a busing schedule so unreasonable and harsh that ... the

health, safety, and security of the children involved have been

compromised by their exposure to risks and dangers." Under the

1971 remedial order, black children in grades 1-4 _in fact have

been bused out to schools in predominantly white areas for

46/desegregation. There, in any event, is no evidence of

any unavoidable endangerment or impingement as a result of

transportation at these levels. See Lee v. Macon County Board

47/

of Education, 616 F.2d 805, 810-811 (5th Cir. 1980).

46/ The plan submitted by the board in 1980 proposed the same kind of busing. 492 F. Supp. at 181-183.

47/ Plaintiffs did object to the discriminatory busing of only BTack children in grades 1-4 to schools in predominantly white

areas. Plaintiffs' educational consultant, Dr. Hugh Scott,

testified that one-way busing of black students in grades 1-4 to

39