North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1970. f9874dc0-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77fe7573-daf5-40a7-9cba-e3bcb7fcdc49/north-carolina-state-board-of-education-v-swann-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

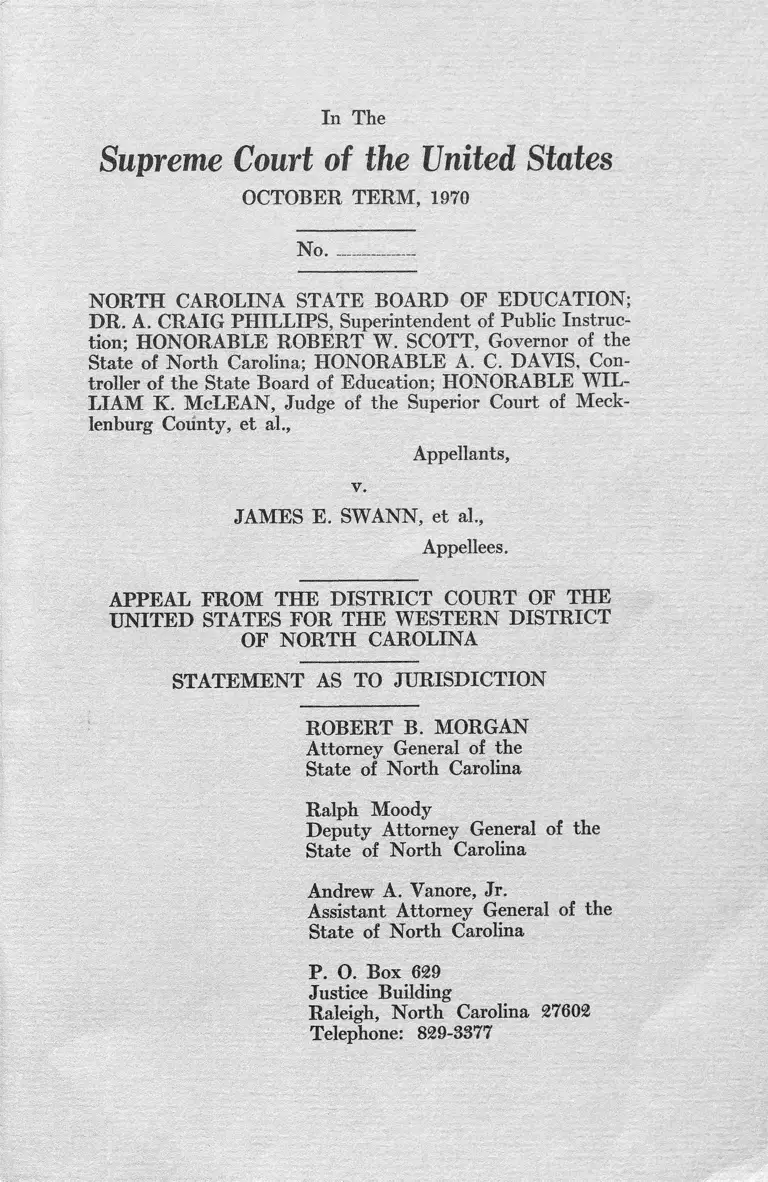

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM , 1970

No________

NORTH CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION;

DR. A. CRAIG PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion; HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Governor of the

State of North Carolina; HONORABLE A. C. DAVIS. Con

troller of the State Board of Education; HONORABLE W IL

LIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the Superior Court of Meck

lenburg County, et ah,

Appellants,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

ROBERT B. MORGAN

Attorney General of the

State of North Carolina

Ralph Moody

Deputy Attorney General of the

State of North Carolina

Andrew A. Vanore, Jr.

Assistant Attorney General of the

State of North Carolina

P. O. Box 629

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: 829-3377

INDEX

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION......................................... 1

OPINION BELOW .......................................................................... 1

JURISDICTION ................................................................................ 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........................................................... 4

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

INVOLVED ................................................................................ 4

CONCLUSION ................................................. 13

TABLE OF CASES

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U. S. 19, 90 S. Ct. 29 ........................................................ 10

Atlantic Coastline Railroad v. Brotherhood of Locomotive

Engineers, No. 477, October Term, 1969, Opinion filed

June 8, 1970 .............................................................................. 13

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F. 2d 209, cert.

den. 377 U. S. 924 .................................................................. 8

Blue v. Durham Public School District, 95 F. Supp. 441 .......... 12

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v.

Dowell, 375 F. 2d 158, cert. den. 387 U. S. 931 .................. 8

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Florida,

v. Braxton, 402 F. 2d 900 ....................................................... 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686,

98 L. ed. 873 ............................................................................. 7

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294,

99 L. ed. 1083, 75 S. Ct. 753 ..................................................... 7

Brown v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

267 N. C. 740, 743, 149 S. E. 2d 10 ....................................... 11

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310,

315, 316 ..................................................................................... 7

i

Constantian v. Anson County, 244 N, C. 221, 93 S. E. 2d 163 .... 12

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (CCA-4) .......................... 13

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55,

cert. den. 389 U. S. 847 ........................................................... 8

Department of Employment v. United States, 385 U. S. 355,

87 S. Ct. 464, 17 L. ed. 2d 414 ................................................ 3

Dilday v. Board of Education, 267 N. C. 438, 148

S. E. 2d 513 .............................................................................. 12

Down v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F. 2d

988, cert. den. 380 U. S. 914 ................................................. 8

Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v. Jacobsen,

362 U. S. 73, 8 S. Ct. 568, 4 L. ed. 2d 568 .......................... 2

Grave v. Board of Education of North Little Rock, Arkansas,

School District, 299 F. Supp. 843 ........................................... 8

Huff v. Board of Education, 259 N. C. 75, 130 S. E. 2d 26 ........ 11

In Re Hays, 261 N. C. 616, 135 S. E. 2d 645 ................................ 12

Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 ............................................. 13

McKissick v. Durham City Board of Education,

176 F. Supp. 3 ........................................................................ 13

Mitchell v. Donovan, No. 726, October Term, 1969,

Opinion filed June 15, 1970 ................................................... 13

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis,

_____U. S---------- - 25 L. ed. 2d 246, 90 S. Ct........... ................ 10

Palmetto Fire Insurance Company v. Conn, 272 U. S. 205,

47 S. Ct. 88, 71 L. ed. 243 ....................................................... 3

Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 ................................................. 11

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F. 2d 836, 879 .................................................................. 8

Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U. S. 1, 85 S. Ct. 1271, 14 L. ed. 2d 179 ....... 3

ii

STATUTES

General Statutes of North Carolina, §115-176.1 .............. 2, 3, 4, 5

General Statutes of North Carolina, §115-180 .......................... 10

General Statutes of North Carolina, §115-181 .......................... 11

General Statutes of North Carolina, Chapter 115, Article 22

28 USC 1253 ............................................................... 2

42 USC 2000c ................................................................................. 5, 6

42 USC 2000C-6 ....................... 5

APPENDIX ....................................................................................... 14

FINAL JUDGMENT ........................................................................ 15

OPINION OF 3-JUDGE COURT .................................................. 16

DESIGNATION OF 3-JUDGE COURT ..................................... 30

NOTIFICATION AND REQUEST FOR DESIGNATION

OF 3-JUDGE COURT ......... 32

SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT .................................................. 36

ORDER TO ADD DEFENDANTS AND TO FILE

SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT ......................................... 50

MOTION FOR SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT AND

ADDITIONAL DEFENDANTS ............................................. 51

ANSWER TO SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT ........................ 55

MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF AND ADDITIONAL

DEFENDANTS ........................................................................ 59

ORDER ALLOWING ADDITIONAL DEFENDANTS .............. 65

ANSWER TO MOTION TO ADD ADDITIONAL

DEFENDANTS AND FOR FURTHER RELIEF .............. 69

DEPOSITION OF JAMES H. CARSON, JR................................ 76

iii

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM , 1970

No.

NORTH CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION;

DR. A. CRAIG PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion; HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Governor of the

State of North Carolina; HONORABLE A. C. DAVIS, Con

troller of the State Board of Education; HONORABLE W IL

LIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the Superior Court of Meck

lenburg County, et ah,

Appellants,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et ah,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

The appellants, pursuant to United States Supreme Court

Rules 13 and 15, file this statement as to jurisdiction, setting

forth the basis upon which it is contended that the Supreme

Court of the United States has jurisdiction on a direct appeal

from an opinion and judgment of a 3-judge federal court to

review the final judgment in question, and, further, that this

Court should exercise such jurisdiction in this case.

OPINION BELOW

The 3-Judge Federal District Court for the Western Dis

trict of North Carolina filed its written opinion on April 29,

1970; this opinion is not yet reported. A copy of the opinion

is attached to the Jurisdictional Statement and appears on

p. 16 of the Appendix attached hereto.

2

JURISDICTION

The appeal herein is from a judgment decided by a 8-

judge federal court organized in the Western District of North

Carolina and filed in the Office of the Clerk of the Court for

the Western District of North Carolina on June 22, 1970,

the same being a final judgment. In this judgment the 3-

Judge Federal Court held unconstitutional and invalid a por

tion of a statute of North Carolina (Section 115-176.1 of

the General Statutes of North Carolina-—1969 Cumulative

Supplement to Volume 3A) which said portion reads as

follows:

“No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend

any school on account of race, creed, color or national

origin, or for the purpose of creating balance or ratio

of race, religion or national origins. Involuntary busing

of students in contravention of this article is prohibited,

and pubilc funds shall not be used for any such busing.”

The 3-Judge Federal District Court further held that except

for the portion above quoted the State statute was con

stitutional and valid.

The complete statute appears on p. 19 of the Appendix

attached hereto.

The final judgment signed by the 3-Judge Federal Court

declaring this portion of the State statute unconstitutional

and restraining any action to enforce same on the part of

the appellants is set forth on p. 15 of the Appendix attached

hereto.

The Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdiction

to review by direct appeal the opinion and judgment of the

3-Judge District Court of the United States herein complained

of by virtue of the provisions of 28 USC 1253. This is also

a question that arises under the provisions of the Constitution

of the United States.

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the Su

preme Court of the United States to review this opinion and

judgment on direct appeal in this case: FLORIDA LIME &

3

AVOCADO GROWERS, INC. v. JACOBSEN, 362 U. S. 73,

8 S. Ct. 568, 4 L„ ed. 2d 568; ZEMEL v. RUSK, 381 U. C. 1, 85

S. Ct. 1271, 14 L. ed. 2d 179; PALMETTO FIRE INS. CO. v.

CONN, 272 U. S. 205, 47 S. Ct. 88, 71 L. ed. 243; DEPART

M ENT OF EM PLOYMENT v. UNITED STATES, 385 U. S.

355, 87 S. Ct. 464, 17 L. ed. 2d 414.

It is to be noted that the 3-Judge Federal Court granted an

injunction against all of the State officers restraining them

from carrying out the provisions of the statute above cited.

This would seem to bring the case directly in line with the

decisions where this Court will take jurisdiction and hear

such an appeal.

It should be emphasized that the appellants do not ques

tion the organization of the 3-Judge Federal Court. The ap

pellants concede that the constitutionality of the State statute

was a proper case which requires a 3-judge court to pass upon

the constitutional and injunctive issue. It is further conceded

that the 3-Judge Federal Court was properly organized under

a proper order, and, therefore, the jurisdiction of the 3-Judge

Court to hear the case is not questioned.

The portion of Sec. 115-176.1 (1969 Supplement to Vol

ume 3A) of the statutes of North Carolina declared to be

unconstitutional consists of two sentences in said statute which

we again quote, as follows:

“ No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend any

school on account of race, creed, color or national origin,

or for the purpose of creating balance or ratio of race,

religion or national origins. Involuntary busing of students

in contravention of this article is prohibited, and public

funds shall not be used for such busing.”

The 3-Judge Federal Court construed these two sentences

to mean that they prohibited assignment by race and would

prevent school boards from altering existing dual systems. Ap

parently the Court construed the word “ balance” as prohi

biting a school board from establishing the so-called Unitary

System, and the Court said this violated the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Aside from the con

stitutional implications involved in the statute, we think the

Court has incorrectly construed the language of the statute

since the 3-Judge Court evidently thought that the language

substantially prohibited all busing.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

THE 3-JUDGE FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA ERRED,

AS FOLLOWS:

I. IN HOLDING AND CONCLUDING THAT THE

NORTH CAROLINA STATUTE ABOVE QUOT

ED VIOLATED THE EQUAL PROTECTION

CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH AM END

MENT.

II. IN ERRONEOUSLY CONSTRUING THE WORD

“BALANCE” AS USED IN THE NORTH CARO

LINA STATUTE TO BE A PROHIBITION

AGAINST RACIAL ADJUSTMENT IN THE OR

GANIZATION OF A PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM

AND IN CONSTRUING THE STATUTE TO

MEAN THAT BUSING SHOULD NOT BE RE

SORTED TO BUT AS FLATLY PROHIBITING

BUSING.

III. IN HOLDING IN SUBSTANCE THAT THE

STATE HAS NO CONTROL OVER THE EXPEN

DITURE OF ITS FUNDS, BUT, TO THE CON

TRARY, MUST EXPEND ITS FUNDS ACCORD

ING TO THE DICTATION OF THE FEDERAL

COURT.

IV. IN FAILING TO DISMISS THE ACTION AS

AGAINST THE STATE OFFICIALS WHO ARE

NOT CONCERNED W ITH THE BUSING OF

THE PUPILS WHICH IS PURELY THE FUNC

TION OF THE LOCAL SCHOOL UNITS.

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

N.C.G.S. 115-176.1 (The portion of this statute as quoted

above); Article 22 of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of

5

North Carolina (Dealing with the rights and duties as to the

busing of public school pupils).

Section 115-176.1 of the North Carolina

General Statutes is constitutional

This portion of the statute simply prohibits compulsory at

tendance or assignment of any pupil to a public school on

account of race, creed, or national origin, for the express pur

pose of creating a balance or ratio of race, religion or national

origins. It also prohibits involuntary busing of students “ in

contravention of this article” and provides that public funds

shall not be used for such busing.

This is in line with the enactment of the Congress in the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the definition of “ desegregation”

in subsection (b) of 42 USC 2000c it is expressly said:

“ ‘Desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students to

public schools to overcome racial imbalance.” Likewise, in 42

USC 2000c-6, it is provided in subsection (a) (2), as follows:

“Provided that nothing herein shall empower any official

or court of the United States to issue any order seeking

to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the

transportation of pupils or students from one school to

another or one school district to another in order to

achieve such racial balance,”

Apparently Senator Humphrey, when this matter was be

ing debated on the floor of the Senate, held an opinion quite

contrary to the order of the Court in this matter. In 110 Con

gressional Record 12717, we find the following:

“ Mr. Humphrey * * * I should like to make one further

reference to the Gary case. This case makes it quite,clear

that while the Constitution prohibits segregation, it does

not require integration * * * . The bill does not attempt

to integrate the schools but it does attempt to eliminate

segregation in the schools * * * . The fact that there is

a racial imbalance per se is not something which is un

constitutional. That is why we have attempted to clarify

it with the language in Section 4.”

6

It is submitted that the definition of “ desegregation” is on

a par with the congressional definition, which is found in sub

section (b) of 42 USC 2000c, which is as follows:

“ ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students to

public schools and within such schools without regard to

their race, religion, or national origin, but ‘desegregation’

shall not mean the assignment of students to public

schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.”

If the first sentence of the State Statute is therefore un

constitutional, then the Congressional Act is likewise uncons

titutional and invalid. If this sentence is unconstitutional, then

that portion of the State statute which forbids exclusion from

a school on the basis of race is also uncontstitutional for these

two statutory prohibitions are different statements of the

same thing. The first of these provisions says to the school

authorities that you cannot require a child because of his

race to stay away from any given school. The second pro

vision says to the school authorities you cannot require a

child, because of his race, to enter any given school. The

thrust of these two provisions is that school attendance based

entirely on race is prohibited.

The holding of the 3-Judge Federal Court in this case should

be scrutinized closely from a constitutional standpoint. What

the District Court has done, as well as courts elsewhere, is

simply to convert a civil right or civil liberty into a civil

obligation analogous to the obligation of compulsory con

scription for military purposes.

The whole scheme of busing pupils on a racial basis to re

move a racial imbalance in a public school is not only a

dictatorial exertion of power on the part of the judiciary but

is a confusion between civil rights and civil obligations. It

means that parents and pupils must submit to the judge's

choice of the schools they shall attend based upon the color of

their skin to accomplish a fictitious governmental purpose. It

simply means that black people or white people are directed by

judicial dictat to go to one school rather than to another.

Judicial dictation or tyranny by an all-powerful government

is not removed because it is done in the name of equality. In

7

other words, black people, or, for that matter, white people,

are under a governmental obligation to associate with whom

ever the government chooses because the government has

decided to compel such association, and, therefore, the civil

right to associate with whomsoever citizens choose to associate

with is not a right but a governmental obligation. If this

doctrine is pushed to the limits of its logic, then the Four

teenth Amendment is constitutional authority for totalitar

ianism for the government can deprive citizens of their rights

or of their civil liberties if it merely deprives all citizens equal

ly of such liberty or right.

If a black person enters a common carrier, such as a bus,

he has a right to sit down at the front of the bus where the

white people were formerly accustomed to having their seats,

or he has a right to go to the back of the bus where the

black people were formerly seated. He may choose any seat

on the bus he desires, but if he decides to sit at the back of

the bus, it is submitted that the bus driver has no constitu

tional right to go back and seize him by the collar and drag

him up to front of the bus. In this connection certain langu

age in the case of BRADLEY v. SCHOOL BOARD OF

RICHMOND, 345 F. 2d 310, 315, 316 (4th Cir. 1965), the

Court dealt with the argument of certain black plaintiffs who

wished their children to attend schools predominantly attend

ed by black people. The Court said:

“ To that extent, they (plaintiffs) say that, under any

freedom of choice system, the state ‘permits’ segregation

if it does not deprive Negro parents of a right of choice.

* * * There is nothing in the Constitution which prevents

his voluntary association with others of his race or which

would strike down any state law which permits such

association. The present suggestion that a Negro’s right

to be free from discrimination requires that the state

deprive him of his volition is incongruous.”

There is nothing in Brown I or Brown II that supports

the ruling of the Court (BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCA

TION, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873; BROWN

v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, 349 U. S. 294,

8

99 L. ed. 1083, 75 S. Ct. 753) . It is noticeable, and, in fact,

it should be emphasized, that Brown II is utterly silent as

to redressing racial imbalance, but, to the contrary, deals with

school districts and attendance areas. The Court said:

“ The burden rests upon the defendants to establish at

such time as is necessary in the public interest and is con

sistent with good faith compliance at the earliest prac

ticable date. To that end, the courts may consider prob

lems related to administration, arising from the physical

condition of the school plant, the school transportation

system, personnel, revision of school districts and at

tendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of

determining admission to the public schools on a nonraeial

basis, and revision of local laws and regulations which

may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems.”

It is submitted, therefore, that nondiscriminatory zoning or

attendance areas related to the neighborhood school to which

pupils are admitted on a nonraeial basis is the proper solution

(see: BELL v. SCHOOL CITY OF GARY, INDIANA (CCA-

7 ), 324 F. 2d 209, cert. den. 377 U. S. 924; UNITED STATES

v. JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

(CCA-5), 372 F.2d 836, 879; DEAL v. CINCINNATI BOARD

OF EDUCATION, 369 F. 2d 55 (CCA-6), cert. den. 389

U. S. 847; BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF DUVAL

COUNTY, FLORIDA v. BRAXTON (CCA-5), 402 F. 2d

900; DOWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF KANSAS

CITY (CCA-10), 336 F. 2d 988, cert. den. 380 U. S. 914;

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS v. DOWELL (CCA-10), 375 F. 2d 158, cert. den.

387 U. S. 931; GRAVE v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

NORTH LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS SCHOOL DIS

TRICT, 299 F. Supp. 843).

The mention of the school transportation system in Brown

II refers to the existing school transportation and not to the

creation of new transportation systems to redress racial im

balance.

An examination of the orders entered by District Judge

McMillan, as shown in the Appendix to Petition for Certiorari

9

in No. 1713, October Term, 1969, already before this Court,

will show that the District Judge has proposed to organize

the public schools of Charlotte on the basis of mathematical

ratios and not only do this but keep students in constant

motion, moving from one school to another during the term,

based upon computer calculations.

If what we have said as to the constitutionality of the

first sentence in the judgment below is true, then the second

sentence, which prohibits the expenditure of public funds for

involuntary busing to redress racial imbalance, is also a valid

exercise of State power.

The statute does not prohibit normal

transportation for a public school sys

tem. It only prohibits busing to relieve

a racial imbalance or to provide public

schools whose attendance is based on

mathematical ratios.

It seems quite clear to us that the 3-Judge Court has mis

construed the language of the statute. Among other things,

the Court said:

“ Stated differently, a statute favoring the neighborhood

school concept, freedom-of-choice plans, or both, can

validly limit a school board’s choice of remedy only if

the policy favored will not prevent the operation of a

unitary system. That it may or may not depends upon

the facts in a particular school system. The flaw in this

legislation is its rigidity. As an expression of State policy,

it is valid. To the extent that it may interfere with the

board’s performance of its affirmative constitutional duty

to establish a unitary system, it is invalid.”

What the Court is really saying is that students may be

bused to rectify a racial imbalance or to conform to a math

ematical ratio. In another part of the opinion the Court said:

“ The second and third sentences are unconstitutional.

They plainly prohibit school boards from assigning, com

pelling, or involuntarily busing students on account of

race, or in order to racially ‘balance’ the school system.”

10

What the Court has really said is that there must be a

unitary system without defining the unitary system. The Court

has also said that students may be bused to establish racial

balance, or, in other words, to correct a racial imbalance,

which is the very thing prohibited by the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. It seems strange that the Congress can prohibit this

course of action and yet the State cannot prohibit the same

course or type of action. The Court furthermore assumes that

busing to redress racial imbalance is a constitutionally ap

proved governmental objective and is a required constitution

al obligation which has yet to be decided, and as far as

this Court has gone is to say that a unitary system was one

“ within which no person is to be effectively excluded from

any school because of race or color.” (ALEXANDER v.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, 396 U. S.

19, 90 S. Ct. 29, quoted in concurring opinion in NORTH-

CROSS v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF MEMPHIS, ____

U. S. ____ , 25 L. ed. 2d 246, 90 S. Ct. ------ ) Thus it will be

seen that the Court has exceeded that part of the definition

already given.

The Court also overlooks the fact that neither the local

board of education nor the State defendants are compelled

to operate a transportation system.

In Section 115-180 of the General Statutes of North Caro

lina it is said:

“ Each county board of education, and each city board of

education is hereby authorized, but is not required, to

acquire, own and operate school buses for the transport

ation of pupils enrolled in the public schools of such

county or city administrative unit and all persons em

ployed in the operation of such schools within the limit

ations set forth in this subchapter. Each such board may

operate such buses to and from such of the schools within

the county or city administrative unit, and in such num

ber, as the board shall from time to time find practicable

and appropriate for the safe, orderly and efficient trans

portation of such pupils and employees of such schools.”

11

The State Board of Education has no authority over the

transportation of pupils. In a portion of Section 115-181 of

the General Statutes of North Carolina we find the following:

“ (a) The State Board of Education shall not have

authority over or control of the transportation of pupils

and employees upon any school bus owned and operated

by any county or city board of education, except as

provided in this subchapter.

“ (b) The State Board of Education shall be under no

duty to supply transportation to any pupil or employee

enrolled or employed in any school. Neither the State

nor the State Board of Education shall in any manner be

liable for the failure or refusal of any county or city

board of education to furnish transportation, by school

bus or otherwise, to any pupil or employee of any school,

or for any neglect or action of any county or city board

of education, or any employee of any such board, in the

operation or maintenance of any school bus.”

The State Board of Education does allocate to the respec

tive county and city boards of education all funds appro

priated from time to time by the General Assembly for the

purpose of providing transportation to the pupils enrolled

in the public schools within the State. These funds are al

located according to the number of pupils to be transported,

the length of bus routes, road conditions and all other cir

cumstances affecting the cost of transportation of pupils. The

Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State has no

duties in regard to transportation and the Governor of the

State has no duties relating to school transportation. The

Supreme Court of North Carolina has construed these statutes

to relieve the State Board of Education from all duties in

the field of transportation (HUFF v. BOARD OF EDUCA

TION, 259 N. C. 75, 130 S. E. 2d 26; BROWN v. CHAR-

LOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, 267

N. C. 740, 743, 149 S. E. 2d 10). And in the case of SPAR

ROW v. GILL, 304 F. Supp. 86 (1969), a 3-judge federal

court said:

“ The State may allocate its funds on any basis it chooses

12

— or may cut off funds entirely— so long as it does not ca

priciously favor one group of citizens over another.”

The order of the 3-Judge Court, therefore, requires the

State to furnish funds to provide public school busing to

redress a racial imbalance even though the amount of such

funds exceeds the amount appropriated for normal trans

portation or exceeds the entire appropriation of the General

Assembly. We do not contend that school boards are pro

hibited from changing the racial organization of any par

ticular school facility to provide constitutional schools and

that buses may be used to transport to any of the facilities.

We do contend that children cannot be changed around and

bused far beyond the school in a pupil’s residence area simply

to redress racial imbalance or that pupils may be moved

around during the school term to maintain mathematical

ratios.

The holding of the 3-Judge Court deprives

the State of control over its funds.

While we have already discussed to some extent this subject,

it should be stated that we are not aware of the proposition

that a 3-judge federal court may order a State to expend its

funds in a particular manner or to require the General As

sembly of a State to appropriate funds according to the federal

court. It has not yet been held by this Court that a State

is required and that it is its constitutional duty to furnish

funds according to some federal judicial formula.

The Court erred in failing to sustain

the Motion to Dismiss all of the

State defendants.

All federal judges in the State of North Carolina, except

one, have held that the State Board of Education, the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction and other State officers

do not control and administer the public school system but

such power is lodged in the local units (CONSTANTIAN v.

ANSON COUNTY, 244 N. C. 221, 93 S. E. 2d 163; DILDAY

v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 267 N. C. 438, 148 S. E. 2d

513; IN RE HAYS, 261 N. C. 616, 135 S. E. 2d 645; BLUE

v. DURHAM PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT, 95 F. Supp.

13

441; JEFFERS V . WHITLEY, 165 F. Supp, 951; McKISSICK

v. DURHAM CTTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, 176 F.

Supp. 3).

In the case of COVINGTON v. EDWARDS, CCA-4, 264

F. 2d 780, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit upheld this same principle. The 3-Judge Federal Court,

therefore, should have dismissed this action against all the

defendants. The defendant, Judge McLean, should not have

been restrained from proceeding with the suit in the State

Court (MITCHELL v. DONOVAN, No. 726, October Term,

1969, Opinion filed June 15, 1970; ATLANTIC COASTLINE

RAILROAD v. BROTHERHOOD OF LOCOMOTIVE EN

GINEERS, No. 477, October Term, 1969, Opinion filed June

8, 1970).

CONCLUSION

We conclude, therefore, that this Court should accept juris

diction in this case. We further assert that quotas for religious

minorities are not approved; quotas have been revised in

our national immigration laws; quotas in alien employment

rights have not been approved. We submit that quotas should

not be approved in the public school system as between the

races anymore than proportional representation in the jury

system which this Court has expressly diapproved. Black

pupils are entitled to go to the public schools on the same

basis as white pupils and all this Court has decided in the

Brown Cases is that the State must eliminate State sources

of racial discrimination.

Respectfully submitted,

ROBERT B. MORGAN

Attorney General of the

State of North Carolina.

RALPH MOODY

Deputy Attorney General of

the State of North Carolina

ANDREW A. VANORE, JR.

Assistant Attorney General of

the State of North Carolina

P. O. Box 629

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Telephone: 829-3377

14

APPEN DIX

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

CHARLOTTE DIVISION

Civil No. 1974

JAMES E. SWANN, et al, Plaintiffs,

versus

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG B O A R D

OF EDUCATION, a public body corporate;

W ILLIAM E. POE; HENDERSON BELK;

DAN HOOD; BEN F. HUNTLEY; BETSEY

KELLY; COLEMAN W. KERRY, JR.; JULIA

MAULDEN; SAM McNINCH, III; CARL

TON G. WATKINS; THE NORTH CARO

LINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, a

public body corporate; and DR. A. CRAIG

PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion of the State of North Carolina, Defendants,

and

HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Gover

nor of the State of North Carolina; HONOR

ABLE A. C. DAVIS, Controller of the State

Department of Public Instruction; HONOR

ABLE W ILLIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the

Superior Court of Mecklenburg County; TOM

B. HARRIS; G. DON ROBERSON; A.

BREECE BRELAND; JAMES M. POSTELL;

W ILLIAM E. RORIE, JR.; CHALMERS R.

CARR; ROBERT T. WILSON; and the CON

CERNED PARENTS ASSOCIATION, an un

incorporated association in Mecklenburg Coun- Additional

ty; JAMES CARSON and W ILLIAM H. Parties

BOOE, Defendant.

15

CIVIL NO. 2631

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, et al, Plaintiffs,

versus

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG B O A R D

OF EDUCATION and WILLIAM C. SELF,

Superintendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Pub

lic Schools, Defendants.

FINAL JUDGMENT

Upon reconsideration of our memorandum opinion filed

April 28, 1970, we withdraw Part V.

It is now ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that

the following portion of N. C. General Statute 115-176.1

prohibiting assignment by race and bussing be and hereby is

held unconstitutional, void, and of no effect:

No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend any

school on account of race, creed, color or national origin,

or for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race,

religion or national origins. Involuntary bussing of stu

dents in contravention of this article is prohibited, and

public funds shall not be used for any such bussing.

All parties are hereby enjoined from enforcing, or seeking the

enforcement of, the foregoing portion of the statute.

Plaintiff’s motion to hold defendants in contempt is denied;

the various motions to dismiss are denied.

This 22 day of June, 1970.

J. Braxton Craven

United States Circuit Judge

John D. Butzner, Jr.

United States Circuit Judge

James B. McMillan

United States District Judge

16

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

CHARLOTTE DIVISION

Civil No. 1974

JAMES E. SWANN, et al. Plaintiffs,

versus

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG B O A R D

OF EDUCATION, a public body corporate;

W ILLIAM E. POE; HENDERSON BELK;

DAN HOOD; BEN F. HUNTLEY; BETSEY

KELLY; COLEMAN W. KERRY, JR.; JULIA

MAULDEN; SAM McNINCH, III; CARL

TON G. WATKINS; THE NORTH CARO

LINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, a

public body corporate; and DR. A. CRAIG

PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion of the State of North Carolina, Defendants,

and

HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Gover

nor of the State of North Carolina; HONOR

ABLE A. C. DAVIS, Controller of the State

Department of Public Instruction; HONOR

ABLE WILLIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the

Superior Court of Mecklenburg County; TOM

B. HARRIS; G. DON ROBERSON; A.

BREECE BRELAND; JAMES M. POSTELL;

W ILLIAM E. RORIE, JR.; CHALMERS R.

CARR; ROBERT T. WILSON; and the CON

CERNED PARENTS ASSOCIATION, an un

incorporated association in Mecklenburg Coun- Additional

ty; JAMES CARSON and WILLIAM II. Parties

BOOE, Defendant.

17

Civil No. 2631

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, et al., Plaintiffs,

versus

CHARLOTTEE-MECKLENBURG BOARD

OF EDUCATION and WILLIAM C. SELF,

Superintendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Pub

lic Schools, Defendants.

THREE-JUDGE COURT

(Heard March 24, 1970 Decided April 29, 1970.)

Before CRAVEN and BUTZNER, Circuit Judges, and Mc-

MILLAN, District Judge.

Mr. J. LeVonne Chambers (Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Tan

ning) and James M. Nabrit, III, for Plaintiffs in No. 1974;

Mr. William J. Waggoner (Weinstein, Waggoner, Sturges,

Odom & Bigger) and Mr. Benjamin Horack, for Defendants

in No. 1974; Mr. Ralph Moody, Deputy Attorney General,

and Mr. Andrew A. Vanore, Jr., Assistant Attorney General,

for State Defendants and Additional Parties-Defendant in No.

1974; and Mr. William H. Booe and Mr. Whiteford S. Blake-

ney, for other Additional Parties-Defendant in No. 1974.

Mr. William H. Booe and Mr. Whiteford S. Blakeney for

Plaintiffs in No. 2631; and Mr. William J. Waggoner (Weins

tein, Waggoner, Sturges, Odom & Bigger) for Defendants in

No. 2631.

CRAVEN, Circuit Judge:

This three-judge district court was convened pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 2281, et seq. (1964), to consider a single aspect

of the above-captioned case: the constitutionality and impact

of a state statute, N. C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1 (Supp. 1969),

known as the antibussing law, on this suit brought to de

18

segregate the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system. We hold

a portion of N. C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1 unconstitutional be

cause it may interfere with the school board’s performance of

its affirmative constitutional duty under the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

I.

On February 5, 1970, the district court entered an order

requiring the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board to de

segregate its school system according to a court-approved plan.

Implementation of the plan could require that 13,300 addition

al children be bussed.1 This, in turn, could require up to 138

additional school buses.1 2

Prior to the February 5 order, certain parties filed a suit,

entitled Tom B. Harris, G. Don Roberson, et al. v. William C.

Self, Superintendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools and

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, in the Superior

Court of Mecklenburg County, a court of general jurisdiction

of the State of North Carolina. Part of the relief sought was

an order enjoining the expenditure of public funds to pur

chase, rent or operate any motor vehicle for the purpose of

transporting students pursuant to a desegregation plan. A

temporary restraining order granting this relief was entered by

the state court, and, in response, the Swann plaintiffs moved

the district court to add the state plaintiffs as additional par

ties defendant in the federal suit, to dissolve the state restrain

ing order, and to direct all parties to cease interfering with the

federal court mandates. Because it appeared that the con

1. On March 5, 1970, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals stayed

that portion of the district court’s order requiring bussing of

students pending appeal to the higher court.

2. There is a dispute between the parties as to the additional num

ber of children who will be bussed and as to the number of

additional buses that will be needed. For our purposes, it is im

material whose figures are correct. The figures quoted are taken

from the district judge’s supplemental findings of fact, filed

March 21, 1970.

19

stitutionality of N. C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1 (Supp. 1969)

would be in question, the district court requested designation of

this three-judge-court on February 19, 1970. On February 25,

1970, the district judge granted the motion to add additional

parties. Meanwhile, on February 22, 1970, another state suit,

styled Mrs. Robert Lee Moore, et al. v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education and William C. Self, Superintendent of

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, was begun. In this second

state suit, the plaintiffs also requested an order enjoining the

school board and superintendent from implementing the plan

ordered by the district court on February 5. The state court

judge issued a temporary restraining order embodying the relief

requested, and on February 26, 1970, the Swann plaintiffs

moved to add Mrs. Moore, et al., as additional parties defend

ant in the federal suit. On the same day, the state defend

ants filed a petition for removal of the Moore suit to fed

eral court. On March 23, 1970, the district judge requested a

three-judge court in the removed Moore case, and this panel

was designated to hear the matter. All the cases were consoli

dated for hearing, and the court heard argument by all parties

on March 24, 1970.

II.

N. C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1 (Supp. 1969) reads:

Assignment of pupils based on race, creed, color or

national origin prohibited.—No person shall be refused ad

mission into or be excluded from any public school in this

State on account of race, creed, color or national origin.

No school attendance district or zone shall be drawn for

the purpose of segregating persons of various races, creeds,

colors or national origins from the community.

Where administrative units have divided the geographic

area into attendance districts or zones, pupils shall be as

signed to schools within such attendance districts; provid

ed, however, that the board of education of an administra

tive unit may assign any pupil to a school outside of such

20

attendance district or zone in order that such pupil may

attend a school of a specialized kind including but not

limited to a vocational school or school operated for, or

operating programs for, pupils mentally or physically

handicapped, or for any other reason which the board of

education in its sole discretion deems sufficient. No stu

dent shall be assigned or compelled to attend any school

on account of race, creed, color or national origin, or for

the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race, religion

or national origins. Involuntary bussing of students in

contravention of this article is prohibited, and public funds

shall not be used for any such bussing.

The provisions of this article shall not apply to a temp

orary assignment due to the unsuitability of a school for

its intended purpose nor to any assignment or transfer

necessitated by overcrowded conditions or other circum

stances which, in the sole discretion of the school board,

require assignment or reassignment.

The provisions of this article shall not apply to an ap

plication for the assignment or reassignment by the parent,

guardian or person standing in loco parentis of any pupil

or to any assignment made pursuant to a choice made by

any pupil wdio is eligible to make such choice pursuant

to the provisions of a freedom of choice plan voluntarily

adopted by the board of education of an administrative

unit.

It is urged upon us that the statute is far from clear and

may reasonably be interpreted several different ways.

(A) Plaintiffs read the statute to mean that the school

board is prevented from complying with its duty under

the Fourteenth Amendment to establish a unitary school

system. See, e.g., Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968). In support of this con

tention, plaintiffs argue that the North Carolina General

Assembly passed § 115-176.1 in response to an April 23,

21

1909, district court order, which required the school board

to submit a plan to desegregate the Charlotte schools for

the 1909-70 school year. Under plaintiffs’ interpretation of

the statute, the board is denied all desegregation tools

except nongerrymandered geographic zoning and freedom

of choice. Implicit in this, of course, is the suggestion that

zoning and freedom of choice will be ineffective in the

Charlotte context to disestablish the asserted duality of

the present system.

(B) The North Carolina Attorney General argues that

the statute was passed to preserve the neighborhood school

concept. Under his interpretation, the statute prohibits

assignment and bussing inconsistent with the neighbor

hood school concept. Thus, to disestablish a dual system

the district court could, consistent with the statute, only

order the board to geographically zone the attendance

areas so that, as nearly as possible, each student would be

assigned to the school nearest his home regardless of his.

race. Implicit in this argument is that any school system

is per se unitary if it is zoned according to neighborhood

patterns that are not the result of officially sanctioned

racial discrimination. Although the Attorney General em

phasizes the expression of state policy by the Legislature

in favor of the neighborhood school concept, he recognizes,

of course, that the statute also permits freedom of choice

if a school board voluntarily adopts such a plan. Thus, the

plaintiffs and the Attorney General read the statute in

much the same way: that it limits lawful methods of

accomplishing desegregation to nongerrymandered geo

graphic zoning and freedom of choice.

(C) The school board’s interpretation of the statute is

more ingenious. The board concedes that the statute pro

hibits assignment according to race, assignment to achieve

racial balance, and involuntary bussing for either of these

purposes, but contends that the facial prohibitions of the

statute only apply to prevent a school board from doing

22

more than necessary to attain a unitary system. The

argument is that since the statute only begins to operate

once a unitary system has been established, it in no way

interferes with the board’s constitutional duty to de~

segrate the schools. Counsel goes on to insist that Char-

lotte-Mecklenburg presently has a unitary system and,

therefore, that the state court constitutionally applied the

statute to prevent further unnecessary racial balancing.

(D) Plaintiffs in the Harris suit contend (1) that in

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c (b) and 2000c-6 (a) (2) (1964)3 Con

gress expressly prohibited assignment and bussing to

achieve racial balance, (2) that to compel a child to at

tend a school on account of his race or to compel him to

be involuntarily bussed to achieve a racial balance violates

the principle of Brown v. Bd. of Ed. of Topeka, 347 U.S.

483 (1954), and (3) that N. C. Gen. Stat. § 115-176.1

merely embodies the principle of the neighborhood school

in accordance with Brown and the Civil Rights Act of

1964. We may dispose of the first contention at once. The

statute “ cannot be interpreted to frustrate the constitu

tional prohibition [against segregated schools].” United

3.

§ 2000c:

As used in this subchapter—

(b) “Desegregation” means the assignment of students to

public schools and within such schools without regard to their

race, color, religion, or national origin, but “desegregation” shall

not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order

to overcome racial imbalance.

§ 2000c-6(a):

(2) [Provided that nothing herein shall empower any official

or court of the United States to issue any order seeking to

achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the trans

portation of pupils or students from one school to another or

one school district to another in order to achieve such racial

balance, or otherwise enlarge the existing power of the court to

insure compliance with constitutional standards.

23

States v. School Dist. 151 of Cook Co., 404 F. 2d 1125,

1130 (7th Cir. 1968).

(E) Plaintiffs in the Moore suit argue that the district

court order of February 5, 1970, was in contravention of

Brown and, therefore, that the state court order in their

suit was justified. However, the Moore plaintiffs also argue

that certain parts of the second and third paragraphs in

the state statute are unconstitutional because they give

the school board the authority to assign children to

schools for whatever reasons the board deems necessary

or sufficient. The Moore plaintiffs interpret these portions

of the statute as permitting assignment and bussing on

the basis of race contrary to Brown and the Fourteenth

Amendment.

III.

Federal courts are reluctant, as a matter of comity and

respect for state legislative judgment and discretion, to strike

down state statutes as unconstitutional, and will not do so

if the statute reasonably can be interpreted so as not to

conflict with the federal Constitution. But to read the statute

as innocuously as the school board suggests would, we think,

distort and twist the legislative intent. We agree with plain

tiffs and the Attorney General that the statute limits the

remedies otherwise available to school boards to desegregate

the schools. The harder question is whether the limitation

is valid or conflicts with the Fourteenth Amendment. We

think the question is not so easy, and the statute not so

obviously unconstitutional, that the question may lawfully be

answered by a single federal judge, see Turner v. City of

Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (1962); Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S.

31 (1962), and we reject plaintiffs’ attack upon our juris

diction. Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U. S. I l l (1965); C.

Wright, Law of Federal Courts § 50 at 190 (2d ed. 1970).

In Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent Co., 391 U. S.

430 (1968), the Supreme Court declared that a school board

24

must take effective action to establish a unitary, nonracial

system, if it is not already operating such a system. The

Court neither prohibited nor prescribed specific types of plans,

but, rather, emphasized that it would judge each plan by

its ultimate effectiveness in achieving desegregation. In Green

itself, the Court held a freedom-of-choice plan insufficient be

cause the plan left the school system segregated, but stated

that, under the cirumstances existing in New Kent County,

it appeared that the school board could achieve a unitary

system either by simple geographical zoning or by consoli

dating the two schools involved in the case. 391 U. S. at

442, n. 6. Under Green and subsequent decisions, it is clear

that school boards must implement plans that work to achieve

unitary systems. Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. of the Memphis

City Schools,------ U. S---------, 38 L.W. 4219 (1970) ; Alexander

v. Holmes Co. Bd. of Ed., 396 U. S. 19 (1969) . Plans that do

not produce a unitary system are unacceptable.4

We think the enunciation of policy by the legislature of

the State of North Carolina is entitled to great respect.

Federalism requires that whenever it is possible to achieve

a unitary system within a framework of neighborhood schools,

a federal court ought not to require other remedies in dero

gation of state policy. But if in a given fact context the

state’s expressed preference for the neighborhood school cannot

be honored without preventing a unitary system, it is the

former policy which must yield under the Supremacy Clause.

Stated differently, a statute favoring the neighborhood

school concept, freedom-of-choice plans, or both can validly

4. The reach of the Court’s mandate is not yet clear:

[A]s soon as possible . . . we ought to resolve some of the

basic practical problems when they are appropriately presented

including whether, as a constitutional matter, any particular

racial balance must be achieved in the schools; to what extent

school districts and zones may or must be altered as a con

stitutional matter; to what extent transportation may or must

be provided to achieve the ends sought by prior holdings of the

Court.

25

limit a school board’s choice of remedy only if the policy

favored will not prevent the operation of a unitary system.

That it may or may not depends upon the facts in a particular

school system. The flaw in this legislation is its rigidity. As

an expression of state policy, it is valid. To the extent that

it may interfere with the board’s performance of its affir

mative constitutional duty to establish a unitary system, it

is invalid.

The North Carolina statute, analyzed in light of these

principles, is unconstitutional in part. The first paragraph

of the statute reads:

No person shall be refused admission into or be exclud

ed from any public school in this State on account of

race, creed, color or national origin. No school attendance

district or zone shall be drawn for the purpose of segre

gating persons of various races, creeds, or national origins

from the community.

Northcross v, Bd. of Ed. of the Memphis City Schools, -------

U. S. ____, 38 L.W. at 4220 (1970) (Chief Justice Burger,

concurring). For our purposes, it is sufficient to say that the

mandate applies to require “ reasonable” or “ justifiable” solu

tions. See generally Fiss, Racial Imbalance in the Public

Schools: The Constitutional Concepts, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564

(1965).

There is nothing unconstitutional in this paragraph. It is

merely a restatement of the principle announced in Brown v.

Bd. of Ed. of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) (Brown I).

The third paragraph of the statute reads:

The provisions of this article shall not apply to a

temporary assignment due to the unsuitability of a school

for its intended purpose nor to any assignment or trans

fer necessitated by overcrowded conditions or other cir

cumstances which, in the sole discretion of the school

board, require assignment or reassignment.

26

This paragraph merely allows the school board noninvidious

discretion to assign students to schools for valid administra

tive reasons. As we read it, it does not relate to race at all and,

so read, is constitutional.

The fourth paragraph provides:

The provisions of this article shall not apply to an

application for the assignment or reassignment by the

parent, guardian or person standing in loco parentis of

any pupil or to any assignment made pursuant to a choice

made by any pupil who is eligible to make such choice

pursuant to the provisions of a freedom of choice plan

voluntarily adopted by the board of education of an

administrative unit.

This paragraph relieves school boards from compliance with

the statute where they are implementing voluntarily adopted

freedom-of-choice plans within their systems. It does not re

quire the boards to adopt freedom of choice in any particular

situation, but leaves them free to comply with their con

stitutional duty by any effective means available, including,

where it is appropriate, freedom of choice. So interpreted,

the paragraph is constitutional.

The second paragraph of the statute contains the consti

tutional infirmity. It reads:

Where administrative units have divided the geographic

area into attendance districts or zones, pupils shall be

assigned to schools within such attendance districts; pro

vided, however, that the board of education of an ad

ministrative unit may assign any pupil to a school out

side of such attendance district or zone in order that

such pupil may attend a school of a specialized kind

including but not limited to a vocational school or school

operated for, or operating programs for, pupils mentally

or physically handicapped, or for any other reason which

the board of education in its sole discretion deems suf

ficient. No student shall be assigned or compelled to

27

attend any school on account of race, creed, color or

national origin, or for the purpose of creating a balance

or ratio of race, religion or national origins. Involuntary

bussing of students in contravention of this article is

prohibited, and public funds shall not be used for any

such bussing.

The first sentence of the paragraph presents no greater con

stitutional problem than the third and fourth paragraphs of

the statute, discussed above. It allows school boards to

establish a geographically zoned neighborhood school system,

but it does not require them to do so. Consequently, this

sentence does not prevent the boards from complying with

their constitutional duty in circumstances where zoning and

neighborhood school plans may not result in a unitary system.

The clause in the first sentence permitting assignment for

“ any other reason” in the board’s “ sole discretion” we read

as meaning simply that the school boards may assign outside

the neighborhood school zone for noninvidious administrative

reasons. So read, it presents no difficulty. The second and

third sentences are unconstitutional. They plainly prohibit

school boards from assigning, compelling, or involuntarily

bussing students on account of race, or in order to racially

“ balance” the school system. Green v. School Bd. of New Kent

Co., 391 U. S. 430 (1968), Brown v. Bd. of Ed. of Topeka, 349

U. S. 294 (1955) (Brown I I ) , and Brown v. Bd. of Ed of

Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) (Brown I), require school boards

to consider race for the purpose of disestablishing dual systems.

The Constitution is not color-blind with respect to the

affirmative duty to establish and operate a unitary school

system. To say that it is would make the constitutional prin

ciple of Brown I and II an abstract principle instead of an

operative one. A flat prohibition against assignment by race

would, as a practical matter, prevent school boards from alter

ing existing dual systems. Consequently, the statute clearly

contravenes the Supreme Court’s direction that boards must

take steps adequate to abolish dual systems. See Green v.

28

School Bd. of New Kent Co., 391 U. S. 430, 437 (1968) . As

far as the prohibition against racial “ balance” is concerned,

a school board, in taking affirmative steps to desegregate its

system, must always engage in some degree of balancing. The

degree of racial “ balance” necessary to establish a unitary

system under given circumstances is not yet clear, see North-

cross v. Bd. of Ed. of the Memphis City Schools, ........ U. S.

____, 38 L.W. at 4220 (1970) (Chief Justice Burger concur

ring) , but because any method of school desegregation in

volves selection of zones and transfer and assignment of pupils

by race, a flat prohibition against racial “ balance” violates

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Finally, the statute’s prohibition against “ involuntary bus

sing” also violates the equal protection clause. Bussing may

not be necessary to eliminate a dual system and establish a

unitary one in a given case, but we think the Legislature

went too far when it undertook to prohibit its use in all

factual contexts. To say that bussing shall not be resorted

to unless unavoidable is a valid expression of state policy, but

to flatly prohibit it regardless of cost, extent and all other

factors— including willingness of a school board to experiment

— contravenes, we think, the implicit mandate of Green that

all reasonable methods be available to implement a unitary

system.

Although we hold these statutory prohibitions unconstitu

tional as violative of equal protection, it does not follow that

“ bussing” will be an appropriate remedy in any particular

school desegregation case. On this issue we express no opinion,

for the question is now on appeal to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and is not for us to decide.

It is clear that each case must be analyzed on its own

facts. See Green v. School Bd. of New Kent Co., 391 U. S. 430

(1968). The legitimacy of the solutions proposed and ordered

in each case must be judged against the facts of a particular

school system. We merely hold today that North Carolina may

not validly enact laws that prevent the utilization of any

29

reasonable method otherwise available to establish unitary

school systems. Its effort to do so is struck down by the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the

Supremacy Clause (Article VI, clause 2 of the Constitution) .

V.

As we have no cause to doubt the sincerity of the various

defendants, the plaintiffs’ motion to hold them in contempt

for interference with the district court’s orders and their

request for an injunction against enforcement of the statute

will be denied. We believe the defendants, including the state

court plaintiffs, will, pending appeal, respect this court’s judg

ment, which applies statewide with respect to the constitu

tionality of the statute.

Several of the parties have moved to be dismissed from

the case, alleging various grounds in support of their motions.

Because of the view we take of this suit and the limited relief

we grant, the motions to dismiss become immaterial. The

school board is undeniably a proper party before the court

on the constitutional issue, since it is a party to the desegre

gation suit. We can, therefore, consider and adjudge the

validity of the statute, regardless of the position of the other

parties. That we consider the substantive arguments of all

the parties in no way harms those who have moved to be

dismissed.

An appropriate judgment will be entered in accordance with

this opinion.

30

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Division

Civil Action No. 1974

JAMES E. SWANN, et al, Plaintiffs,

v

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD

OF EDUCATION, a public body corporate;

WILLIAM E. POE; HENDERSON BELK;

DAN HOOD; BEN F. HUNTLEY; BETSEY

KELLY; COLEMAN W. KERRY, JR.; JULIA

MAULDEN; SAM McNINCH, III; CARL

TON G. WATKINS; THE NORTH CARO

LINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, a

public body corporate; and DR. A. CRAIG

PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion of the State of North Carolina,

Defendants,

and

HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Gover

nor of the State of North Carolina; HONOR

ABLE A. C. DAVIS, Controller of the State

Department of Public Instruction; HONOR

ABLE WILLIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the

Superior Court of Mecklenburg County; TOM

B. HARRIS; G. DON ROBERSON; A.

BREECE BRELAND; JAMES M. POSTELL;

WILLIAM E. RORIE, JR.; CHALMERS R.

CARR; ROBERT T. WILSON; and the CON

CERNED PARENTS ASSOCIATION, an un

incorporated association in Mecklenburg Coun

ty; JAMES CARSON and WILLIAM H.

BOOE,

Additional Parties Defendant

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

) DESIGNA-

) TION OF

) THREE-

) JUDGE

) COURT

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

31

It appearing to the undersigned Chief Judge of the Fourth

Judicial Circuit of the United States that a civil action as

above-entitled has been instituted in the United States District

Court for the Western District of North Carolina, and that a

motion and application for restraining order and other relief

have been filed in this action which do or may raise the ques

tion of the constitutionality of Section 115-176,1 of the General

Statutes of North Carolina, commonly spoken of as the “ anti

bussing” statute and which application and motion also raise

other questions; and that application for relief as set out in

the pending motion and order was made to James B. M c

Millan, United States District Judge for the Western District

of North Carolina, who has notified the undersigned, pursuant

to Section 2284 of Title 28, United States Code, of the pen

dency of such application to the end that a court of three

judges may be constituted in accordance with Section 2281,

Title 28, United States Code.

Now, therefore, I do hereby designate Honorable J. Braxton

Craven, Jr., United States Circuit Judge, Fourth Judicial

Circuit, and Honorable John D. Butzner, Jr., United States

Circuit Judge, Fourth Judicial Circuit, to serve with the

Honorable James B. McMillan in the hearing and deter

mination of the above-entitled action, as provided by law,

the three to constitute a district court of three judges as pro

vided by Section 2284, Title 28, United States Code.

This the 23rd day of February, 1970.

Clement F. Haynsworth, Jr.

Chief Judge - Fourth Circuit

32

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Division

Civil Action No. 1974

JAMES E. SWANN, et al, Plaintiffs, )

v )

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD }

OF EDUCATION, a public body corporate; '

WILLIAM E. POE; HENDERSON BELK; '

DAN HOOD; BEN F. HUNTLEY; BETSEY '

KELLY; COLEMAN W. KERRY, JR.; JULIA '

MAULDEN; SAM McNINCH, III; CARL- '

TON G. WATKINS; THE NORTH CARO

LINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, a '

public body corporate; and DR. A. CRAIG '

PHILLIPS, Superintendent of Public Instruc- ,

tion of the State of North Carolina, '

Defendants,

and '

HONORABLE ROBERT W. SCOTT, Gover- )

nor of the State of North Carolina; HONOR- )

xABLE A. C. DAVIS, Controller of the State )

Department of Public Instruction; HONOR- )

ABLE WILLIAM K. McLEAN, Judge of the )

Superior Court of Mecklenburg County; TOM )

B. HARRIS; G. DON ROBERSON; A. )

BREECE BRELAND; JAMES M. POSTELL; )

WILLIAM E. RORIE, JR.; CHALMERS R. )

CARR; ROBERT T. WILSON; and the CON- )

CERNED PARENTS ASSOCIATION, an un- )

incorporated association in Mecklenburg Coun- )

ty; JAMES CARSON and WILLIAM H. )

BOOE, )

Additional Parties Defendant )

NOTIFI

CATION

AND RE

QUEST

FOR DE

SIGNA

TION OF

THREE-

JUDGE

COURT

33

Several orders, starting April 23, 1969, have been entered by

this court dealing with pending motions for desegregation of

the Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools. The orders of December

1 and December 2, 1969, and February 5, 1970, are attached

as Exhibits A, B and C to this motion.

The December 2, 1969, order appointed Dr. John A. Finger,

Jr. to assist the court in the preparation of a plan for the

desegregation of the schools. The February 5, 1970, order

directs the schools to be desegregated according to various prin

ciples described or referred to in the order, including the

requirement erroneously advertised as “ involuntary bussing

to achieve racial balance” which reads as follows:

“That transportation be offered on a uniform nonracail

basis to all children whose attendance in any school is

necessary to bring about the reduction of segregation,

and who live farther from the school to which they

are assigned than the Board determines to be walking

distance.”

A suit has been filed in the General Court of Justice, Su

perior Court Division, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina,

No. 70-CVS-1097, entitled “ TOM B. HARRIS, G. DON RO

BERSON, et al, Plaintiffs, vs. W ILLIAM C. SELF, Superin

tendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, and CHAR

LOTTE BOARD OF EDUCATION, Defendants,” and pur

suant to allegations made in that action, Judge W, K. McLean,

of the Superior Court of North Carolina, has entered an

order temporarily restraining the School Board and the Su

perintendent from paying Dr. Finger’s bills until they have

been approved by the Board of Education, and ordering that

“ the defendant Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

and its agents, servants and employees be and they hereby

are enjoined and restrained from expending any money from

tax or other public funds for the purpose of purchasing or

renting any motor vehicles, or operating or maintaining such,

for the purpose of involuntarily transporting students in the

34

Charlotte-Mecklenburg School System from one school to

another and from one district to another district.”

The complaint, the amended complaint and the two orders

of Judge McLean dated February 12, 1970, are attached

hereto as Exhibit D.

The Governor of North Carolina has made a public state

ment, Exhibit E, and has written a letter to the Department

of Administration, Exhibit F.

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction, a party to

this case, has made a public statement, Exhibit G.

Reports received from the School Board on February 12,

1970, and February 19, 1970, fail to mention Judge McLean’s

order, and fail to indicate that the Board have appealed or

intend to appeal Judge McLean’s order; and these reports also

reveal no action by the Board or school staff addressed to the

transportation problem. It appears that whether the action of

Judge McLean and the other state officials do or do not direct

ly conflict with this court’s orders, the practical effect of those

actions is or may be to delay or defeat compliance with the

orders of this United States Court.

The plaintiffs have filed a motion to make additional parties,

and have requested this court to enter orders dissolving Judge

McLean’s restraining orders and directing the Governor, the

State Department of Instruction and the “Concerned Parents

Association” and their attorneys and others not to interfere

further with the compliance of the school Board with the

orders of this court.

Some of the issues raised by this situation may involve the

constitutionality of a state statute and others may be matters

cognizable by a single judge.

It appearing to the court that pursuant to Title 28, U.S.C.A.,

this matter should be heard and determined by a district court

of three judges.

35

NOW, THEREFORE, it is respectfully requested that the

Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit designate two other judges, at least one of whom

shall be a circuit judge, to serve with the undersigned district

judge as members of the court to hear and determine the action.

This the 19th day of February, 1970.

James B. McMillan

United States District Judge

36

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

CHARLOTTE DIVISION

JAMES E. SWANN, et al, )

Plaintiffs )

v )

)

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD )

OF EDUCATION, a public body corporate; )

WILLIAM E. POE; HENDERSON BELL: )

DAN HOOD; BEN F. HUNTLEY; BETSEY ) CIVIL

KELLY; COLEMAN W. KERRY, JR.; JULIA ) ACTION

MAULDEN; SAM McNINCH, III; CARL- ) NO. 1974

TON G. WATKINS; THE NORTH CARO- )

LINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, a )

public body corporate; and DR. A. CRAIG )

PHILLIPS, SUPERINTENDENT OF PUB- )

LIC INSTRUCTION OF THE STATE OF )

NORTH CAROLINA, )

Defendants )

SUPPLEMENTAL COMPLAINT

I.

This Supplemental Complaint is a proceeding for a tempor

ary restraining order and a preliminary and permanent in

junction against the enforcement of the portions of North

Carolina General Statutes §115-176.1, (Chapter 1274 of the

Session Laws of the 1969 General Assembly of North Carolina,

ratified on July 2, 1969, a copy of which is attached hereto

as Exhibit A) which reads:

“ No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend any

school on account of race, creed, color or national origin,

or for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race,

37

religion or national origin. Involuntary bussing of stu

dents in contravention of this Article is prohibited, and

public funds shall not be used for any such bussing.”

In addition, plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment that the

statutory provisions complained of are unconstitutional on

their face and as applied.

II.

A. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 USC § 1343,

this being a suit in equity authorized by 42 USC § 1983 to

redress the deprivation, under color of North Carolina Law, of

rights, privileges and immunities guaranteed by the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States.

B. Jurisdiction is further invoked under 28 USC § § 2281

and 2284, this being a suit for a temporary restraining order,

an interlocutory and permanent injunction restraining the en

forcement, operation and execution of portions of North Caro

lina General Statutes § 115-176.1 and requiring the convening

of a three-judge Federal Court. Jurisdiction is further invoked

under 28 USC § § 2201 and 2202, this being a suit for a declar

atory judgment declaring the unconstitutionality of portions of

North Carolina General Statutes 115-176.1.

III.

A. The plaintiffs bringing this Supplemental Complaint are

those plaintiffs who originally brought this action styled James

E. Swann, et ah, v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, Civil Action No. 1974, which was filed on January 12,

1965.

B. This Supplemental Complaint, as the original complaint,

is brought on behalf of the individual plaintiffs and other black

students and parents similarly situated, pursuant to Rule 23 (a)

and (b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. There are

common questions of law and fact affecting the rights of such

other black students, who are and have been limited, classi

38

fied, segregated or otherwise discriminated against in ways

which deprive or tend to deprive them of equal educational