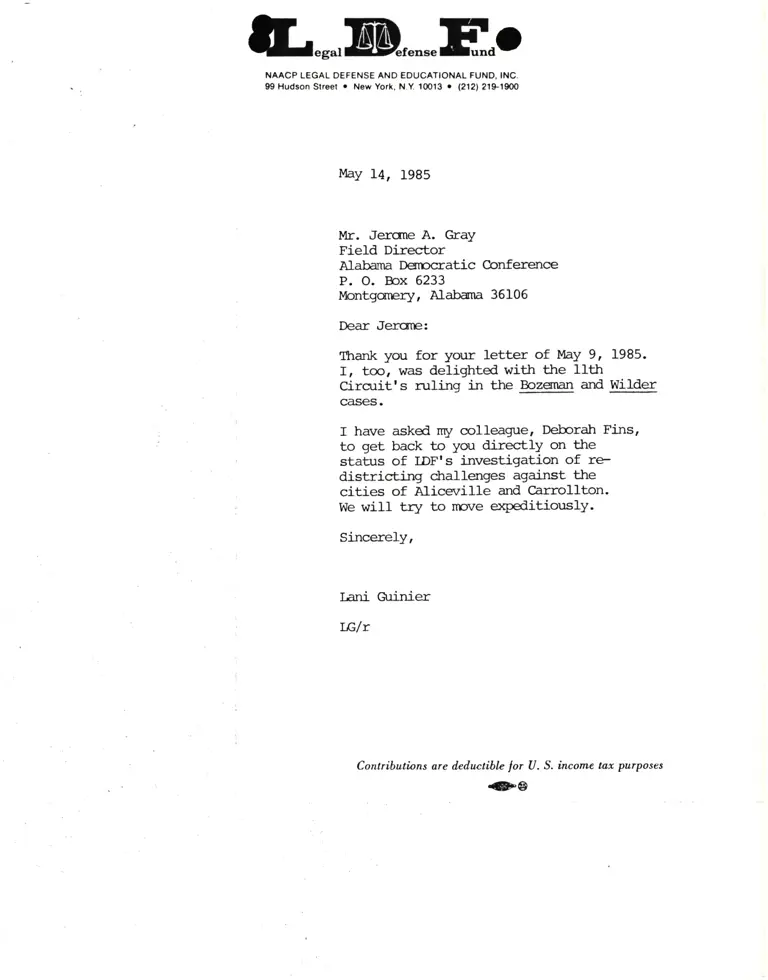

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jerome Gray (Alabama Democratic Conference) Re Bozeman and Wilder v. Lambert

Correspondence

May 14, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Jerome Gray (Alabama Democratic Conference) Re Bozeman and Wilder v. Lambert, 1985. 91bbb5a2-e792-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/77ff1ced-dc32-46b6-8d61-6ed09f146d4a/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-jerome-gray-alabama-democratic-conference-re-bozeman-and-wilder-v-lambert. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

tL.*,ED,",,.Huo

NAACP LEGAL OEFENSE AND EOUCATIONAL FUNO, INC.

09 Hudson Stre€l . New York, N.Y. 10013 o (212) 21$1900

Itlay 14, 1985

IrIr. Jerqne A. C,ray

Fie1d Director

Alabama Ogrpsatic Confo:ence

P. O. Box 6233

lbntgcnery, Alabana 36106

Dear Je:ure:

Ihark you for yo.rr letter of ltlay 9, 1985.

I, too, was delighted with the llttt

Circuit's mling i:: the Bozsnan ard Wilder

cases.

I have asked my col1eagir.re, Deborah Fins,

to get bacl< to ycr.r directly on the

statrrs of LDFrs invesLigation of re

districting ctrallenges against the

cities of Alicqrilte and Ca:ro1lton.

We will tqf to rnnze orpeditiously.

Sincerely,

Lani Ari.:rier

IE/T

Contributions are ded,trctibl,e lor U. S. income tax purPoses

+e