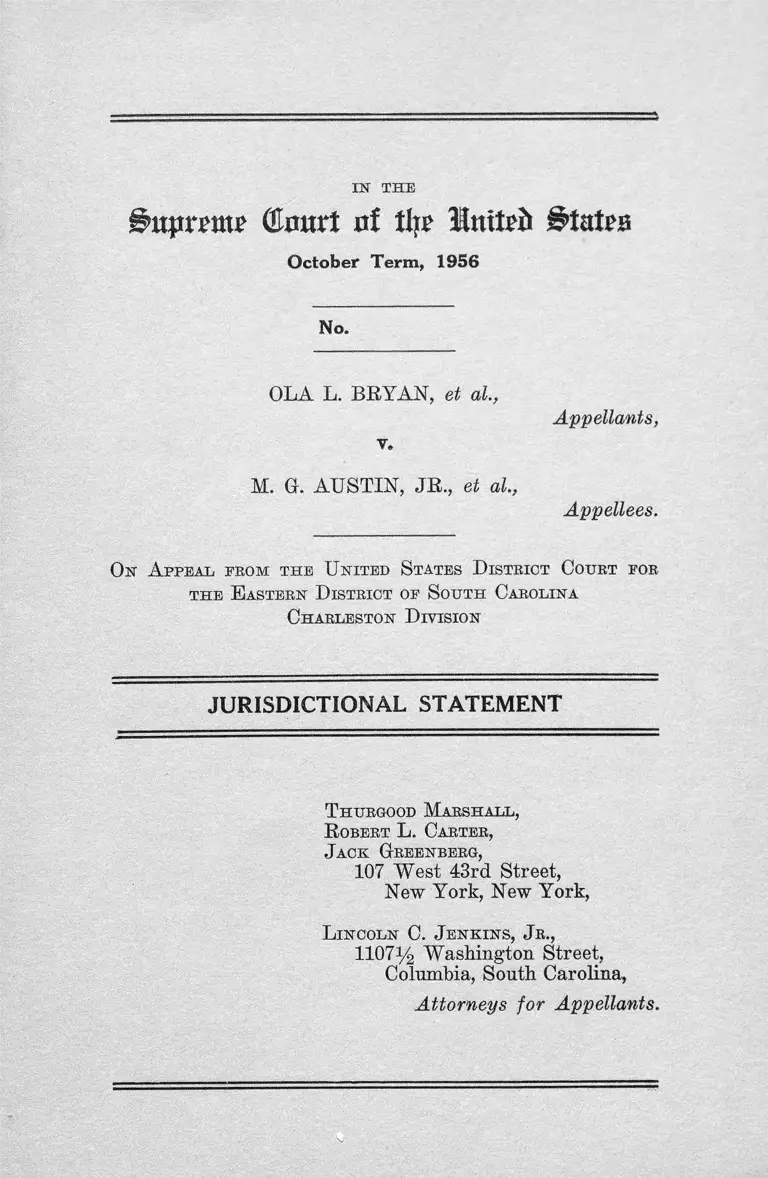

Bryan v Austin Jr Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 22, 1957

71 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryan v Austin Jr Jurisdictional Statement, 1957. ce2f1701-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/781f23be-2caa-4cb5-8e49-8f27ea64db1a/bryan-v-austin-jr-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Ilmtrt at tip United States

October Term, 1956

No.

OLA L. BRYAN, et at.,

v.

Appellants,

M. G. AUSTIN, JR., et al,

Appellees.

O n A ppeal ebom th e U nited S tates D istrict Court eor

th e E astern D istrict oe S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

JURISDICTIONAL STATEM ENT

T hurgood M arshall ,

R obert L . Carter,

J ack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r .,

1107^ Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellants.

I N D E X

Opinions Below ..............................................................

Jurisdiction ...................................................................

Question Presented ........................................................

Statutes Involved ..........................................................

Statement ................... ............... ....................................

The Questions Are Substantial...................................

1. Act No. 741 destroys free speech .................

2. Act No. 741 denies equal protection of the

la w s.....................................................................

3. Act No. 741 is a bill of attainder...................

4. Act No. 741 would destroy the liberty to

advocate school desegregation .....................

5. Appellants should not have been remitted to

state cou rts ........................................................

6. Appellants should not have been relegated to

■so-called administrative rem edies.................

7. The District Court abused its discretion . . .

Table of Cases

Adkins v. The School Board of the City of Newport

News, 148 F. Supp. 430 (E. I). Va., decided Jan.

11, 1957) ......................... ...........................................

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern

Railroad Co., 341 U. S. 341 (1951) .........................

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 ...........................

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

992, 997 (4th Cir., 1940) cert, denied 311 II. S.

693 .................................................................................

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S.

583 .................................................................................

PAGE

1

2

3

3

5

7

7

8

11

13

13

9

11

11

6,7

11

ii

PAGE

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 499 ......................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) 8

Burns v. United States, 287 U. S. 216 ......................... 14

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

336, 337 (E. D, La. 1956) ........................................... 8

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County,

277 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir., 1955) ................................. 9

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir., 1956),

cert, den. — U. S. — ................................................ 9

Chicago, B. & Q. R. Company v. Osborne, 265 U. S.

1 4 ..................................................................................... 2

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheaton 264, 404 ................. 14

Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277 ......................... 7, 8

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 364-365 ............. 6

Dyke v. Geary, 244 U. S. 39 ....................................... 2

Eichholz v. Public Service Commission, 306 U. S

268 .................................................................................

Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission, 271

U. S. 583, 594 .............................................................. 6

Ex parte Garland, 4 Wall. 333 .................................. 7

Government and Civic Employees Organizing Com

mittee, CIO et al. v. Windsor, 116 F. Supp. 354,

357 (N. D. Ala. 1953) afF’d 347 U. S. 9 0 1 .............. 2,11

Hanover Fire Insurance Co. v. Carr, 272 U. S. 494 .. 6

Henderson Water Co. v. Corp. Comm, of 1ST. C., 269

U. S. 278 ...................................................................... 2

Hillsboro Township v. Cromwell, 326 U. S. 620, 628-9 12

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77, 90-94 ....................... 7

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 .................................... 13

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. NAACP, Inc, (La.

App. First Cir.) ....................................................... 10

Louisiana ex rel. LeBlanc v. Lewis, unreported, No

55899 (D. C., 19th Jud. Dist.) 10

Dudley v. Board of Supervisors of L. S. IT. and Agri

cultural & Mechanical College, etc,, Apr. 16,1957 —

F. Supp. — (1 9 5 7 )............'.......... ............................. 8

Montana National Bank v. Yellowstone County, 276

U. S. 499 .......................................................... ‘ .......... 13

Propper v. Clark, 337 U. S. 472 ................................... 12

Public Utilities Company v. United Fuel Gras Com

pany, 317 U. S. 456, 468, 469 ..................................... 12

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 II. S. 389 7

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312

U. S. 426 ...................................................................... 11

Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399 (9th Cir., 1955) . . 12

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ............................. 7

Slochower v. Board of Education of N. Y., 350 U. S.

551, 555 ................................. 6

Southern Pacific v. Denton, 146 U. S. 202 ................. 6

Terra! v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U, S. 529 . . . . 6

Texas v. NAACP Inc. (and NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund Inc.) ................................... 10

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 5 1 6 ................................. 6, 7

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385 ................................. 11

Union Tool Company v. Wilson, 259 U. S. 107 .......... 14

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 .. .. 6

United States Alkali Export v. United States, 325

U. S. 1 9 6 ................................... 13

United States v. Corrick, 298 U. S. 435 ..................... 14

United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303 ...................... 7, 8

Waite v. Macy, 246 U. S. 606 ..................................... 13

Wheeling Steel Corp. v. dander, 337 IT. S. 562 . . . . 7

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 ..................... 6

Williams v. NAACP, Inc., unreported, No. A-58654

(Sup. Ct. Fulton County) ...................................... 10

I ll

PAGE

IV

Other Authorities

Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools ..................... 10

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 237 (1956) ................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 239 (1956 )................................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 241 (1956) ................................. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 421, 418, 426, 420, 424, 450 (1956) 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 422, 449, 592 (1956) ................. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 423 (1956) ................................. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 438 (1956 )................................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 440 (1956) ................................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 443 (1955) ............. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 445 (1956) ................................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 448 (1956) ................................. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 451 (1956)................................. 10

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 571, 576 (1956) ........................... 10

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 586, 588, 730, 731 ........................ 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 728, 943, 944, 942, 927, 776 (1956) 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 730, 941 (1956) .......................... 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 753 (1956) ................................ 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 755 (1956)................................. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 924, 954, 955, 940 (1956).......... 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 928-940 (1956) ............. 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 948 (1956) ................................. 8

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 958 (1956) ................................. 10

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1086 (1956)............................... 10

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1091-1111 (1956) ...................... 9

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1109 (1956) ................................. 9

2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 220, 222, 215, 220-228 ................. 8, 9

Robison, “ Organizations Promoting Civil Rights and

Liberties” ................................................................... 10

Rose, The Negro in A m erica ....................................... 10

Williams and Ryan, Schools in Transition.............. 10

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim C ro w .......... 10

58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949) ...................................... 10

PAGE

V

State Statutes

PAGE

Arkansas Laws of 1957, Acts Nos. 83, 84, 85 .......... 10

Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly

of South Carolina, No. 7 4 1 ..................... 2, 3, 4, 7, 8,11, 13

Code of South Carolina (1952) Section 21-103 . . . . 3,13

Tennessee Public Chapter Nos. 102, 151, 152 (1957) 10

United States Statutes

28 U. S. C. §§ 2281-2284 .................................................. 2, 4

28 U. S. C. § 1253 ............................................................ 2

IN THE

g>upx*mi> (to r t of thr Inttrii ^tatru

October Term, 1956

No.

---------------o---------------

Ola L. B ryan , et al.,

v.

Appellants,

M. G. A u stin , J r ., et al.,

Appellees.

On A ppeal from th e United S tates D istrict C ourt for

the E astern D istrict of S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

-----------------------o----------------------

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the judgment of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of South

Carolina, Charleston Division, entered on January 23,

1957, which denied appellants’ applications for preliminary

and final injunctions to restrain the enforcement of Acts

and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of South

Carolina, 1956, No. 741 and submit this statement to show

that the Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion of this appeal and that a substantial question is

presented.

Opinions Below

The opinions of Judges Williams, Timmerman and

Parker, and the majority opinion in which Judges Timmer

man and Williams concurred which contains the order of

the court in which the latter two Judges concurred, are not

yet reported and are attached hereto as Appendix A.

2

Jurisdiction

This suit was brought in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, Charles

ton Division, under 28 U. S. C. Section 2281-2284 to secure

preliminary and final injunctions against officers of the

State of South Carolina to restrain them from enforcing,

on grounds of unconstitutionality, Act No. 741 of the Acts

and Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of South

Carolina, 1956. The order of the District Court was entered

on January 23, 1957 and Notice of Appeal was filed in

that court on February 20, 1957. The jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review this decision by direct appeal is

conferred by 28 U. S. C. Section 1253 which provides:

“ Except as otherwise provided by law, any party

may appeal to the Supreme Court from an order

granting or denying, after notice and hearing, an

interlocutory or permanent injunction in any civil

action, suit or proceeding required by any Act of

Congress to be heard and determined by a district

court of three judges.”

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review the judgment on direct appeal

in this case: Government and Civic Employees Organizing

Committee v. Windsor, 347 U. S. 901, aff’g 116 F. Supp.

354 (N. D. Ala. 1953) in which the order of the three-judge

court (116 F. Supp. at p. 359) was in language almost

identical to that employed by the district court here. On

appeal this Court exercised jurisdiction and affirmed. The

exercise of jurisdiction in that case demonstrates that this

Court also possesses jurisdiction here, although the affirm

ance merely indicates that the statute there in question,

unlike the legislation involved in this case, was susceptible

of a constitutional construction (116 F. Supp. at p. 357),

as discussed in greater detail, infra, p. 11. See also Van

Dyke v. Geary, 244 U. S. 39; Eichhols v. P. 8. C., 306 U. S.

268; Chicago, B. & Q. R. Company v. Osborne, 265 U. S. 14;

Henderson Water Company v. Corp. Comm, of N. C., 269

U. S. 278.

3

Question Presented

Whether, where appellants, Negro public school teachers,

challenged a South Carolina statute unequivocally forbid

ding state agencies to employ members of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People and

authorizing state officials to demand of state employees

oaths of non-membership in this association, on grounds of

unconstitutionality under the Fourteenth Amendment’s due

process and equal protection clauses and as a Bill of At

tainder prohibited by Article 1, Section 9, Clause 3, the

District Court correctly denied injunctive relief restraining

the statute’s enforcement, relegating plaintiffs to inher

ently ineffectual “ administrative remedies” and to state

courts for a determination of the statute’s constitutionality.

Statutes Involved

Act No. 741 of the Acts and Resolutions of the General

Assembly of South Carolina, 1956; Code of South Carolina

1952, Section 21-103, reprinted herein in Appendix B.

Statement

The principal facts are related succinctly in the opinion

of Judge Williams:

There is no dispute as to the facts. Plaintiffs are

seventeen Negro school teachers, who had been em

ployed in Elloree Training School of School District

No. 7 of Orangeburg County, South Carolina, prior

to June 1956 for varying periods of time, one for as

long as ten years. There is evidence to the effect

that they were competent teachers and there is no

evidence that their service was unsatisfactory in any

way. In March 1956 the Legislature of South Caro

lina passed the act here complained of [Act No. 741,

reprinted in full in Appendix B], one of the pro

visions of which authorized the board of trustees of

any school to demand of any teacher that he submit

4

a statement under oath as to whether or not he was

a member of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People, and provided that any

one refusing to submit such statement should be sum-

. marily dismissed. Other sections of the act made it

unlawful for any member of that association to be

employed by any school district and imposed a fine

of $100 for employing any individual contrary to the

provisions of the Act. When plaintiffs in May of

1956 were given blank applications [set forth in this

Appendix C] by the School Superintendent to be

filled out and sworn to, which contained questions as

to their membership in the Association and their

views as to the desirability of segregation in the

schools, they declined to answer these questions.

Only one of the plaintiffs, however, was a member of

the Association. Upon being told that they would

have to fill in the answers or tender their resigna

tions, they chose the latter course and were not

elected as teachers for the ensuing year. (E. 90-91,

App. pp. 2a-3a),

On September 12,1956, appellants commenced action for

interlocutory and permanent injunctions to restrain the

enforcement of Act No. 741. In their complaint plaintiffs

alleged that the statute in question was unconstitutional in

that it violated Fourteenth Amendment guarantees against

state denial of freedom of speech and assembly (R. 9) and

in that it was a bill of attainder (R. 9). Because plaintiffs

sought to enjoin state officers in the enforcement of a statute

of state wide application a three-judge court consisting of

Chief Judge John J. Parker, District Judges George Bell

Timmerman and Ashton H. Williams, was convened as

provided by 28 U. S. C., Sections 2281-2284. Complete

testimony was taken, argument had, and thereafter, briefs

submitted.

Each member of the District Court wrote a separate

opinion although Judge Timmerman, disagreeing with

Judge Williams’ position, concurred in it (R. 112, App.

p. 28a) to create a majority in support of the order actually

issued (R. 125, App. p. 42a). Judge Williams was of the

5

opinion that the three-judge district court had jurisdiction,

but “ [t] o declare an act of the state legislature unconstitu

tional should be left to the state court” (R. 96, App. p. 8a).

He therefore wrote that “ [t]he ease should not be dis

missed but should be retained and remain pending to per

mit the plaintiffs a reasonable time for the exhaustion of

state administrative and judicial remedies as may be avail

able. . . . ” (R. 97, App. 9 a).

Judge Timmerman was of the opinion that the three-

judge district court did not have jurisdiction because he

believed that the statute in question had not been applied

to the plaintiffs (R. 102, App. p. 18a). Moreover, in his

view the statute in question was entirely constitutional

(R. 107, App. p. 21a).

Judge Parker, agreeing with Judge Williams as to juris

diction, but dissenting as to the majority’s disposition of

the case, was of the opinion that on the law and the uncon

tradicted evidence the statute in question was unconstitu

tional and that the requested relief should have been

granted (R. 124, App. p. 41a). He believed that no con

struction of the statute in question could render it consti

tutional (R. 114, App. p. 30a) (therefore there was no rea

son to remand to the state court), that the so-called ad

ministrative remedy conferred by the statute was judicial,

and need not have been exhausted under Lane v. Wilson,

307 U. S. 268, and that no administrative remedy could cure

the basic defect of unconstitutionality (R. 123, App. pp.

40a-41a), (therefore, there was no reason to remand to state

administrative tribunals).

The Questions Are Substantial

1. Act No. 741 destroys free speech

The legislation in question is a patent attempt to

destroy rights of free speech and association and flies

squarely in the face of the prior decisions of this Court.

The statute complained of is, in the words of Chief Judge

Parker, “ unambiguous and clearly unconstitutional” (R.

6

124, App. p. 41a). The right to belong to a lawful associa

tion is one of those rights of expression and conscience

secured by the First Amendment and incorporated into the

Fourteenth. Wieman v. Up&egraff, 344 U. S. 183; Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353.

Such constitutional rights may not be taken away directly

nor may the enjoyment of a legal privilege, in this case

public employment, be conditioned upon their abandon

ment. As to public employment see: Slochower v. Board of

Education of N. Y 350 U. S. 551, 555; Wieman v. Upde-

graff, 344 U. S. 183, 191-192; United, Public Workers v.

Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75, 100; Alston v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d 992, 997 (4th Cir., 1940), cert, denied,

311 U. S. 693. As to other constitutional rights see: Frost

v. Railroad Commission, 271 U. S. 583 (use of public high

ways) ; Terral v. Burke Construction Go., 257 U. S. 529

(right to do business within state); Hanover Fire Insur

ance Go. v. Carr, 272 U. S. 494 (sam e); Southern Pacific v.

Denton, 146 U. S. 202 (same).1

1 Plaintiffs, of course, have standing to raise the question of the

constitutionality of the statute, for in the words of Judge Parker

(R. 120, App. p. 3 8 a ):

“ . . . one of them is a member of the Association and all have

been denied employment because of their refusal to answer the

questions as to membership in that organization. The school

authorities may, of course, make inquiries of prospective teachers

as to matters bearing upon their character and fitness to teach;

but this is a very different thing from making inquiry as to

membership in an organization which they have a right to join

but membership in which, under state law, bars them of the

right of employment. Just as they have a right not to be denied

employment because of such membership, they have a right not

to be denied employment for refusal to make oath with regard

to the matter. What was required of them was not merely

answers to questions but the filing of a sworn statement. This

was requiring of them a ‘test oath’ relating to membership as

a condition of employment which was clearly an invasion of

their constitutional rights as held in Wieman v. Updegraff, supra.

“ It is argued that plaintiffs are no longer employed by defend

ants and that they have no applications for positions pending

which could be adversely affected by the statute. This is to take

too narrow a view of the rights of plaintiffs, who are public

7

2. Act No. 741 denies equal protection of the laws

Moreover, Act 741 is obviously unconstitutional in

the light of decisions of this Court interpreting the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. To meet

the test of that clause state legislation must make only

reasonable distinctions reasonably related to a valid legis

lative purpose. Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277

U. S. 389 ; Wheeling Steel Cory. v. dander, 337 IT. S. 562;

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535. The ultimate purpose

of Act No. 741 fully discussed infra, pp. 8-9, is to prevent

the full enjoyment of equal protection of the laws in public

education. A more immediate purpose is to stifle discus

sion of the segregation issue. Both ends are illegal. But

even if the statute’s purpose were something else, Act. No.

741 is invalid in that it is not based upon a real and sub

stantial difference. As a “ constitutionally suspect” statute,

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 IT. S. 497, 499, and one lacking the

momentum for respect accorded other regulations, Kovacs

v. Cooper, 336 IT. S. 77, 90-94, Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. 8.

516, 530, no valid justification has been made to support its

having singled out membership in this organization.

3. Act No. 741 is a bill of attainder

Moreover, the statute in question is a bill of attainder,

a legislative act which inflicts punishment without judicial

trial. Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277; Ex parte Gar

land, 4 Wall. 333; United States v. Lovett, 328 IT. S. 303.

Members of the National Association for the Advancement

school teachers by profession whose rights are invaded by the

statute and the inquiries to which they have been subjected

thereunder. They are seeking here a declaration as to their

rights in a suit instituted against representatives of the state

charged with the enforcement of the statute in the locality in

which they reside, in which the provisions of the statute have

been enforced against them, in which they desire to teach and

in which they would naturally seek employment as teachers in

the future.” See also Alston v. School Board of Norfolk, 112

F. 2d 992, 997 (4th Cir., 1940), cert, denied, 311 U. S. 693.

8

of Colored People are, as set forth in these cases, ‘ ‘ easily

ascertainable members of a group” , United States v. Lovett,

328 U. S. 303, 315-316. The fact that the proscription is

in the form of an oath does not save it, Cummings v. Mis

souri, supra. Deprival of public employment is ‘ ‘ punish

ment” within the meaning of the constitutional prohibition

of bills of attainder, United States v. Lovett, supra.

4 . Act No. 741 would destroy the liberty to advocate school

desegregation

This case therefore presents another facet of the

attack mounted by certain states upon this Court’s de

cision in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294.

Like other states 2 South Carolina, whose legislation is

2 As to interposition and nullification : Senate Concurrent Resolu

tion No. 17-XX, Special Session, 1956, of the Florida Legislature,

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 948 (1956) ; House Resolution No. 185, Regular

Session, 1956, of the Georgia General Assembly, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

438 (1956) ; House Concurrent Resolution No. 10, Regular Session,

1956, of the Louisiana Legislature, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 753 (1956) ;

Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 125, Regular Session, 1956, of

the Mississippi Legislature, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 440 (1956) ; House

Resolution No. 1, Tennessee General Assembly, 1957, 2 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 228 (1957) ; Senate Joint Resolution No. 3, 1956 Session of

the Virginia Legislature, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 445 (1956).

As to other attempts at circumvention:

Florida: Ch. 29746 (1955), 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 237 (1956);

Chs. 31380, 31389, 31390, 31391 (1956), 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

924, 954, 955, 940 (1956).

Georgia: Appropriation Act §§7-8, Acts 11, 12, 13, 15, 197

(1956), 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 421, 418, 426, 420, 424, 450 (1956).

Louisiana: Const. Art. XII, §1, La. R. S. 17:331-334, La.

R. S. 17.81.1, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 239 (1956), held unconstitu

tional in Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 138 F. Supp.

336, 337 (E. D. La. 1956), motion for leave to file petition for

writ of mandamus denied, 351 U. S. 948 (1956), aff’d — F. 2d

— (5th Cir. decided March 1, 1957); La. R. S. 17:2131-2135,

La. R. S. 17:443, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 730, 941 (1956) now

declared unconstitutional in Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of

L. S. U. and Agricultural and mechanical College, etc., — F.

Supp. — (E. D., La.), decided April 16, 1957; Acts 28, 248,

9

involved in this case, has enacted statutes of nullifica

tion and interposition3 and other legislation4 designed

to inhibit Negroes seeking school desegregation. South

Carolina would deny freedom of speech and assem

bly in order to achieve its goal, and in this case has taken

the extraordinary step of conditioning the exercise of the

privilege of public employment upon abandonment of the

250, 252, Senate Bill 350, Const. Art. X IX , § 26, 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 728, 943, 944, 942, 927, 776 (1956); House Concurrent

Resolution No. 9, 1956 Session, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 755 (1956).

Mississippi: House Concurrent Resolution No. 21, Regular

Session 1956, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 423 (1956) ; Proposed House

Bill No. 30, Regular Session, 1956 (vetoed by Governor), 1 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 448 (1956); House Bills No. 31, 119, 880 (1956),

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 422, 449, 592 (1956).

North Carolina: Chs. 1-7, 1956 Extra Session, 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 928-940 (1956); Act 336, 1955, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

240 (1956), see Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell

County, 227 F. 2d 789 (4th Cir., 1955) and Carson v. Warlick,

238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir., 1956), cert. den. — U. S. — , 1 L. ed.

2d 664.

Tennessee: Chs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Laws of Tennessee (1957),

2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 220, 222, 215, 220, 215.

Virginia: Ch. 70, Extra Session 1956, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1109 (1956) held unconstitutional in Adkins v. The School

Board of the City of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430 (E. D.

Va., 1957); Chs. 56-71 (1956). 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1091-1111

(1956).

3 Act of February 14, 1956, Calendar No. S. 514 of the South

Carolina Legislature, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 443 (1956).

4 Act 329 (1955), 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 241 (1956) (appropria

tions for operation of a public school system shall cease for a school

from which, and for a school to which, any pupil may transfer pur

suant to order of court). Acts of 1956 : 662 (providing administra

tive remedies for those aggrieved by school assignment) ; 676 (pro

viding that boards of trustees of school districts may prescribe rules

and regulations) ; 677 (making similar provision for county boards

of education) ; 712 (authorizing sheriffs to remove children from

schools) ; 813, § 3 (restricting expenditures of funds to institutions

of higher learning where racial integration is not practiced). 1 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 586, 588, 730, 731.

10

constitutional right of free speech and assembly—in this

case the right to belong to a lawful organization, the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

well-known as the principal organization opposed to racial

segregation.5 It is manifestly of substantial importance

that such a legislative maneuver which flatly denies free

speech and assembly for the purpose of insulating uncon

stitutional segregation from, attack be reviewed and con

demned by this Court.

5 “ Private Attorneys-General: Group Action in the Fight for

Civil Liberties,’ ’ 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949); Ashmore, The Negro

and the Schools 30, 35, 38, 73, 97, 124, 131 (1954); Williams and

Ryan, Schools in Transition 38-39, 52, 55, 60, 71, 73, 79, 92, 96-

106, 127, 130, 137, 139, 161, 179, 182, 202, 222, 224 (1954); W ood

ward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow 110-111 (1955) ; Rose,

The Negro in America 242, 259, 263-267 (1956 ed.) ; Robison,

“ Organizations Promoting Civil Rights and Liberties” , 275 Annals

18, 20 (1951).

Other states opposed to desegregation have attacked this organi

zation in different ways:

Arkansas: Laws of 1957, Acts Nos. 83, 84, 85.

Georgia: Williams v. National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, Inc., unreported, No. A-58654 (Sup. Ct.

Fulton County).

Louisiana: Louisiana ex rel. LeBlanc v. Lewis, unreported,

No. 55899 (D . C., 19th Jud. Dist.), app. dismissed sub nom.

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc., unreported (La. App.

First Cir.) “ since the cause was removed to the United States

District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana, on March 28, 1956

[No. 1678] * * *,” 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 571, 576 (1956).

Mississippi: House Bill No. 33, Regular Session 1956, 1 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 451 (1956).

Tennessee: Public Chapter Nos. 104, 151, 152 (1957).

Texas: Texas v. N. A. A. C. P., Inc. (and N. A. A. C. P.

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.).

Virginia: Chs 31-37 Extra Session 1956; Ordinance adopted

by Board of Supervisors of Halifax County, August 6, 1956,

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 958 (1956).

11

5. Appellants should not have been remitted to state courts

The trial court was patently wrong in relegating plain

tiffs to the state court on the ground that “ to declare an act

of the state legislature unconstitutional should be left to

the state court.” (R-. 96, App. p. 8a). Judge Williams relied

upon this Court’s decision in Railroad Commission of Texas

v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496 and cited other cases in the

same vein, American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327

U. S. 582; Albertson Millard, 345 D. S. 242; Government

and Civic Employees Organising Committee, CIO et al. v.

Windsor, 347 U. S. 901. The majority interprets these

decisions as requiring state courts to pass first upon cases

involving the constitutionality of state legislation. How

ever, those cases hardly stand for such a proposition. As

was pointed out in Alabama Public Service Commission v.

Southern Railroad Company, 341 U. S. 341, 344 (1951),

proceedings in a federal trial court should he stayed only

where there is involved “ construction of a state statute so

ill defined that a federal court should hold the case pending

a definitive construction of that statute in the state courts.”

Indeed in Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385, in which the

district court had upheld the constitutionality of a state

statute this court reversed without staying proceedings for

action by the state courts. In Government and Civic Em

ployees Organising Committee, CIO et al. v. Windsor, 116

F. Supp. 354, 357 (N. D. Ala. 1953) a ff’d 347 U. S. 901, it

was held in the trial court that “ the Act [in question] could

be construed by the state courts simply as prohibiting a

public employee from being a member of or participating

in such an organization for the purpose of collective bar

gaining with the State and as so construed, meet the chal

lenge of unconstitutionality.”

The purpose and effect of Act Ho. 741 are unquestion

able. It contains no ambiguity which could affect its appli

cability or constitutionality. Judge Williams in making his

ruling assumed that the meaning of the statute was “ clear

and unequivocal.” (R. 96, App. p. 8a). None of the counsel

12

for the defendants nor the Attorney General of the State

of South Carolina have suggested a construction of this

statute which could render it constitutional.

Judge Parker wrote below:

“ . . . The rule as to stay of proceedings pend

ing interpretation of a state statute by the courts

of the state can have no application to a case, such

as we have here, where the meaning of the statute is

perfectly clear and where no interpretation which

could possibly be placed upon it by the Supreme

Court of the state could render it constitutional.”

(R. 114, App. p. 30a).

As was held in Propper v. Clark, 337 U. S. 472, 492:

“ The submission of special issues is a useful

device in judicial administration in such circum

stances as existed in the Magnolia Case, 309 US

478, 84 L ed 876, 60 S Ct 628, 42 Am Bankr NS

216; Speetor Case, 323 US 101, 89 L ed 101, 65

S Ct 152; Pieldcrest Case, 316 US 168, 86 L ed

1355, 62 S Ct 986, and the Pullman Case, 312 US

496, 85 L ed 971, 61 S Ct 643, all supra, but in the

absence of special circumstances, 320 US at 236,

237, 88 L ed 14, 15, 64 S Ct 7, it is not to be used

to impede the normal course of action where federal

courts have been granted jurisdiction of the con

troversy.

“ We reject the suggestion that a decision in this

case in the federal courts should be delayed until the

courts of New York have settled the issue of state

law. ’ ’

See also, Public Utilities Comm. v. United Fuel Gas Com

pany, 317 U. S. 456, 468-469; Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d

399 (9th Cir., 1955); Cf. Hillsboro Township v. Cromwell,

326 U. S. 620, 628-9.

13

6. Appellants should not have been relegated to so-called

administrative remedies

Moreover, there was absolutely no justification for

the court below to have remitted plaintiff to a so-called

administrative remedy. It will be noted that the court’s

order does not state what this “ administrative remedy” is.

Section 3 of Act No. 741 (App. p. 46a) perhaps pur

ports to confer an administrative remedy, but mere inspec

tion of this provision indicates that it remits plaintiffs to

the circuit courts of the state. This is a judicial remedy

and not administrative and clearly need not be exhausted.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. 8. 268.®

7. The District Court abused its discretion

The court below manifestly abused its discretion in

remitting plaintiffs to state judicial and administrative

remedies and in not entering the relief requested on the

uncontradicted facts and the clear requirements of the

8 It was suggested by defendants in the court below that elsewhere

in the statutes of South Carolina there is an administrative remedy,

with particular reference to Code of 1952, Section 21-103 (Appen

dix B, p. 47a). Act No. 741 was passed subsequent to Section 21-103

and presumably supersedes it. As Act No. 741 is specifically appli

cable to this case it would appear that plaintiffs have only a state

judicial remedy which need not be exhausted under Lane v. Wilson,

307 U. S. 268. But in any event there is no issue in this case as to

the construction or administration of the school laws which is the

scope of review under 21-103. The only issue is one of constitution

ality which the county board is powerless to adjudicate as Judge

Parker points out. A board perhaps could find that plaintiffs had

actually answered the questionnaire in full or that plaintiff Fulton

(R. 86-87) was not a member of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, but such findings would be absurd,

for this entire proceeding is based upon the fact that plaintiffs had not

filled out the questionnaire and that plaintiff Fulton is a member of

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

It would be futile for plaintiffs to go to a board without authority to

render the relief they require. Montana National Bank v. Yellow

stone County, 276 U. S. 499; Waite v. Macy, 246 U. S. 606; United

States Alkali Export Ass’n v. United States, 325 U. S. 196.

14

United States Constitution. It is an abuse of discretion

for a court to enter an interlocutory injunction when there

is evident want of jurisdiction, United States v. Corrick,

298 U. S. 435. Since, as Judge Parker pointed out below, a

court has “ no more right to decline the exercise of juris

diction which is given, than to usurp that which is not

given” , citing Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheaton 264, 404, in

this case it was an abuse of discretion not to exercise

jurisdiction. The exercise of discretion “ implies conscien

tious judgment, not arbitrary action.” Burns v. United

States, 287 U. S. 216, 222-223, and as Mr. Justice Brandeis

has written, “ does not extend to a refusal to apply well-

settled principles of law to a conceded state of facts” ,

Union Tool Company v. Wilson, 259 U. S. 107, 112. As on

the uncontradicted facts and the clear law the statute in

volved is patently unconstitutional and as there was abso

lutely no justification in remitting plaintiff to state courts

and to non-defined so-called administrative remedies, a pre

liminary injunction should have been entered. As full

testimony had been taken, argument had and briefs sub

mitted, the preliminary injunction should have also been

made final.

We believe therefore that the questions presented by

the appeal are substantial and that they are of public

importance.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood M arshall ,

R obert L . Carter,

J ack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r .,

1107% Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellants.

la

(Opinion of United States District Court, Eastern District

of South Carolina)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E astern D istrict of S outh Carolina

Civil Action No. 5792

Appendix A

o

Ola L . B ryan , E ssie M. D avid, Charles E. D avis, R osa D.

D avis, V ivian V. F loyd, B ee A. F ogan, H attie M.

F u lton , R u th a M. I ngram , M ary E. J ackson , F razier

H. K eitt , L u th er L ucas, J ames B . M ays, L aura P ickett ,

H oward W. S h efton , B etty S m it h , L eila M. S u m m er

and Clarence V. T obin ,

Plaintiffs,

versus

M. Gr. A u stin , Jr., as Superintendent of School District

No. 7, of Orangeburg County, the State of South Caro

lina, and W. B. B ookhart, H arold F elder, T. T. Mc-

E ach ern , E lmo S huler and U lm er W eeks , as the

Board of Trustees of School District No. 7, of Orange

burg County, the State of South Carolina,

Defendants.

— _--------------- o-----------------------

On Application for Injunction.

(Argued October 22, 1956. Decided Jan. 22, 1957.)

Before:

P arker, Circuit Judge, and T im m erm an and W illiam s ,

District Judges.

2a

L incoln G. J e n k in s , J k ., T hurqood M arshall and

J ack Greenberg, Attorneys for Plaintiffs;

A. J. H ydrick , Jr., M arshall W illiam s , R obert M cC.

F igg, Jr., P. H . M cE a c h in , I). W . R obinson , T . C.

Callison , Attorney General of South Carolina and

D aniel R . M cL eod and J ames 8 . V erner, Assistant

Attorneys General of South Carolina, for defendants.

Appendix A

W illiam s , District Judge:

This is an action by Negro school teachers against the

School Superintendent and the Board of Trustees of a

school district in South Carolina. Its purpose is to ob

tain a declaratory judgment that the South Carolina stat

ute making unlawful the employment by the state, or by

a school district of the state, of any member of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People is

unconstitutional and void and to enjoin the enforcement

of the statute in violation of their constitutional rights. As

the defendants are engaged in the enforcement of a statute

of state wide application and injunction is asked against

them, a court of three judges is appropriate for the hear

ing of the case. City of Cleveland v. United States, 323

U. S. 329. Such a court has accordingly been convened,

the parties have been heard, the Attorney General of the

State has been heard orally and by brief, and the parties

after the hearing have been allowed to file additional briefs,

which have been received and considered.

There is no dispute as to the facts. Plaintiffs are

seventeen Negro school teachers, who had been employed in

Elloree Training School of School District No. 7 of Orange

burg County, South Carolina, prior to June 1956 for vary

ing periods of time, one for as long as ten years. There is

evidence to the effect that they were competent teachers

and there is no evidence that their service was unsatis

3a

factory in any way. In March 1956 the Legislature of

South Carolina passed the act here complained of, one of

the provisions of which authorized the board of trustees of

any school to demand of any teacher that he submit a state

ment under oath as to whether or not he was a member of

the National Association for Advancement of Colored Peo

ple, and provided that anyone refusing to submit such

statement should be summarily dismissed. Other sections

of the act made it unlawful for any member of that asso

ciation to be employed by any school district and imposed

a fine of $100 for employing any individual contrary to the

provisions of the Act. When plaintiffs in May of 1956 were

given blank applications by the School Superintendent to

be filled out and sworn to, which contained questions as

to their membership in the Association and their views as

to the desirability of segregation in the schools, they de

clined to answer these questions. Only one of the plain

tiffs, however, was a member of the Association. Upon

being told that they would have to fill in the answers or

tender their resignations, they chose the latter course and

were not elected as teachers for the ensuing year. Three

questions are presented by the case: (1) Is the statute

unconstitutional as plaintiffs contend? (2) Are plaintiffs

in position to raise the question as to its unconstitutional

ity? And (3) Can the court grant plaintiffs any relief in

view of the fact that plaintiffs have resigned as teachers

and others have been elected to their places!

We think we should use our discretion in refusing to

pass on the issues in this controversy at this time. It does

not appear that the statute in question has been inter

preted by a state court, and it is not proper to pass upon

the controversy presented herein until a South Carolina

court has first heard the case and passed upon the consti

tutionality of the Act in question.

In 1941 the United States Supreme Court had before it

the case of Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co.,

Appendix A

4a

312 U. S. 496. This case involved a regulation by a state

commission authorized by statute, and it was contended

that the regulation was in violation of the Equal Protection,

the Due Process and the Commerce Clauses of the Consti

tution. The United States Supreme Court had the fol

lowing statement to make with reference to the three-judge

District Court’s decision which enjoined the enforcement

of the regulation:

“ * * * But no matter how seasoned the judgment

of the district court may be, it cannot escape being

a forecast rather than a determination. The last

word on the meaning of Article 6445 of the Texas

Civil Statutes, and therefore the last word on the

statutory authority of the Railroad Commission in

this case, belongs neither to us nor to the district

court but to the supreme court of Texas. In this

situation a federal court of equity is asked to decide

an issue by making a tentative answer which may be

displaced tomorrow by a state adjudication. Glenn

v. Field Packing Co., 290 U. S. 177; Lee v. Bickell,

292 U. S. 415. The reign of law is hardly promoted

if an unnecessary ruling of a federal court is thus

supplanted by a controlling decision of state court.

The resources of equity are equal to an adjustment

that will avoid the waste of a tentative decision as

well as the friction of a premature constitutional

adjudication. ’ ’

# # #

In the case of American Federation of Labor v. Watson,

327 U. S. 582, 66 S. Ct. 761, 90 L. ed. 873, the Court held

that the bill had equity, but the trial court erred in ad

judicating the merits of the controversy, saying:

“ * * * The crux of the matter is the allegation

that there is an imminent threat to an entire system

Appendix A

5a

of collective bargaining, a threat which, if carried

through, will have repercussions on the relationship

between capital and labor as to cause irreparable

damage. We conclude for that reason that the bill

states a cause of action in equity.

“ As we have said, the District Court passed on

the merits of the controversy. In doing so at this

stage of the litigation, we think it did not follow the

proper course. The merits involve substantial con

stitutional issues concerning the meaning of a new

provision of the Florida constitution which, so far

as we are advised, has never been construed by the

Florida courts. Those courts have the final say as

to its meaning. When authoritatively construed, it

may or may not have the meaning or force which ap

pellees now assume that it has. In absence of an au

thoritative interpretation, it is impossible to know

with certainty what constitutional issues will finally

emerge. What would now be written on the consti

tutional questions might therefore turn out to be

an academic and needless dissertation.” 327 U. S.

at pages 595-596, 66 S. Ct. at page 767.

# # *

Plaintiffs in this case claim that the act in question is

so clear that it should be construed by us and that we

should decide all of the issues. In the case of Albertson v.

Millard, 345 17. S. 242, the issues were equally clear and

free from ambiguity. The appellants challenged the defi

nitions in the act as being void for vagueness. Mr. Justice

Douglas in a dissenting opinion said:

“ * # * There are no ambiguities involving these

appellants. The constitutional questions do not turn

on any niceties in the interpretation of the Michigan

law. The case is therefore unlike Rescue Army v.

Appendix A

6a

Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549, and its forebears

where the nature of the constitutional issue would

depend on the manner in which uncertain and am

biguous state statutes were construed. See especially

A. F. of L. v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582, 598. Here there

are but two questions:

“ (1) Can Michigan require the Communist

Party of Michigan and its Executive Secretary to

register ?

“ (2) Can Michigan forbid the name of any Com

munist or of any nominee of the Communist Party

to be printed on the ballot in any primary or general

election in the state?”

However, the opinion of the Court in this case states:

“ We deem it appropriate in this case that the

state courts construe this statute before the District

Court further considers the action. See Rescue Army

v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549 (1947); American

Federation of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582 (1946);

and Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S.

101 (1944).

“ The judgment is vacated and the cause re

manded to the District Court for the Eastern District

of Michigan with directions to vacate the restrain

ing order it issued and to hold the proceedings in

abeyance a reasonable time pending construction of

the statute by the state courts either in pending

litigation or other litigation which may be insti

tuted.”

The case of Government and Civic Employees Organiz

ing Committee, CIO, et al. v. Windsor, et al., 116 P. Supp.

354, affirmed in a per curiam decision without opinion, 347

U. S. 901, is even stronger than the Albertson case supra.

Appendix A

7a

This case involved a statute prohibiting state public em

ployees from belonging to labor unions or organizations

and provided for forfeiture of certain rights of those who

joined a labor union or organization. The statute was

clear and free from ambiguity. Plaintiffs there took the

same position as the plaintiffs in the case at bar as indi

cated in the district court’s opinion at page 357:

“ Plaintiffs contend that the challenged statute is

self-executing* and that it lends itself to no possible

construction other than that of unconstitutionality

under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. They insist that they do not have to

wait longer before seeking relief in a federal court,

because they think that ‘ Alabama’s Legislature has

used unmistakably simple, clear, and mandatory

language’ and that ‘ there is neither need for inter

pretation of the statute nor any other special cir

cumstance requiring the federal court to stay action

pending proceedings in the State courts.’ Toomer

v. Witsell, 334 U. S. 385, 392, 68 S. Ct. 1156, 1160, 90

L. Ed. 1460. The defendants assert among other

grounds that plaintiffs have not exhausted available

state administrative and judicial remedies and that

consequently this court, as a matter of sound, equi

table discretion, should decline to exercise jurisdic

tion.

# # #

“ The exercise of jurisdiction under the Federal

Declaratory Judgment Act is discretionary and not

compulsory. Smith v. Massachusetts Mutual Life

Ins. Co., 5 Cir., 167 F. 2d 990; Brillhart v. Excess

Ins. Co., 316 17. S. 491, 62 S. Ct. 1173, 86 L. Ed. 1620.

The remedy by injunction is likewise discretionary.

Peay v. Cox, 5 Cir., 190 F. 2d 123.”

Appendix A

8a

The district court withheld exercise of jurisdiction and

retained the case to permit the exhaustion of state admin

istrative and judicial remedies as might be available.

In every case in which the question was raised since

the Pullman ease in 1941, the United States Supreme Court

has held that a district court should not pass on the merits

of a controversy in a case such as the one before us until

the highest court of the state has interpreted the state

constitutional provision, statute, or regulation in question.

City of Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, 316 U. S. 168; Spector

Motor Service v. McLaughlin, Tax Commissioner, 328 U. S.

101; A. F. of L. v. Watson, supra; Shipman v. Dupre, 339

U. S. 321; Albertson v. Millard, supra; Government and

Civic Employees Organising Committee, CIO, et al. v.

Windsor, et al., supra.

In the instant case, there is no question that the Su

preme Court of South Carolina is in a better position than

the federal court to interpret the state statute. The fact

that there might be delay, inconvenience and cost to the

parties does not call for a different conclusion. We are

here concerned with a much larger issue as to the appro

priate relationship between state and federal authorities

functioning as an harmonious whole.

It may be true that the statute in question is clear and

unequivocal but this does not prevent us from exercising

our discretion in requiring that it be submitted to the state

court for interpretation. Government and Civic Employees

Organising Committee, CIO, et al. v. Windsor, et al., supra.

It appears to us that the Michigan and Alabama Acts were

clear and free from ambiguity. The Supreme Court, how

ever, held that the district court should refrain from tak

ing any action until the highest state court had passed upon

the constitutionality of the Act. The state and federal

courts of South Carolina have always worked in perfect

harmony. To declare an act of the state legislature uncon

Appendix A

9a

stitutional should be left to the state court. This, of course,

would not, apply to statutes and constitutional provisions

which have already been declared unconstitutional by the

United States Supreme Court in the school segregation

cases. We hold that the federal court should stay pro

ceedings and permit the state court to pass upon the con

stitutionality of the Act in question. It is only by doing

this that we avoid conflict between state and federal courts

and preserve harmonious relationships which have hereto

fore existed between them.

The case should not be dismissed but should he retained

and remain pending to permit the plaintiffs a reasonable

time for the exhaustion of state administrative and judicial

remedies as may be available; but thereafter such further

proceedings, if any, will be had by this court as may then

appear to be lawful and proper.

I t is so ordered .

Appendix A

A True Copy,

Attest,

E rnest L. A lden

Clerk of U. S. District Court

East. Dist. So. Carolina

(Seal)

Appendix A

(Opinion of United States District Court, Eastern District

of South Carolina, Charleston Division)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E astern D istrict op S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

Civil Action No. 5792

Ola L . B ryan , E ssie M. D avid, C harles E . D avis, R osa D .

D avis, V ivian V. F loyd, B ee A. F ogan, H attie M.

F u lton , R u t h a M . I ngram , M ary E . J ackson , F razier

H . K eitt , L u th er L ucas, J ames B . M ays, L aura P ickett ,

H oward W . S heeton , B etty S m it h , L eila M . S u m m er

and Clarence V. T obin ,

Plaintiffs,

versus

M. G. A u stin , J r ., as Superintendent of School District

No. 7, of Orangeburg County, the State of South Caro

lina, and W . B. B ookhart, H arold F elder, T. T. M c-

E ach ern , E lmo S h u ler and U lm er W eeks, as the

Board of Trustees of School District No. 7, of Orange

burg County, the State of South Carolina,

Defendants.

---------------------- o------------------ .—

On Application for Injunction.

(Argued October 22, 1956. Decided .)

Before:

P arker , Circuit Judge, and T im m erm an and W illiam s ,

District Judges.

11a

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r ., T hubgood M arshall and J ack

Greenberg, Attorneys for Plaintiffs;

A. J. H ydrick , Jr., M arshall W illiam s , R obert M cC. F igg,

J r ., P . H . M cE a c h in , D . W. R obinson , T . C. Callison ,

Attorney General of South Carolina and D aniel R .

M cL eod and J ames S. V erner, Assistant Attorneys

General of South Carolina, for Defendants.

Appendix A

T im m e r m a n , District Judge:

It is to be regretted that the members of this three-judge

Court are not in agreement. In a general way, the order

to be filed herein at the time that the separate opinions of

the members of this Court are filed will correctly state the

differences existing among the members of the Court. As

will be seen by what shall follow, I am. in disagreement

with my colleagues on the main issues in this case.

This action was originally brought by eighteen negro

plaintiffs, former school teachers, against the defendants,

the Superintendent and Board of Trustees of School Dis

trict No. 7, Orangeburg County, South Carolina, in which

Elloree Training School is situate. As stated in plaintiffs ’

brief, the purpose of the action is to enjoin the defendants

from “ (1) refusing to continue plaintiffs’ employment as

school teachers solely because of their membership in the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple; (2) requiring plaintiffs to supply information con

cerning their beliefs and associations particularly with re

spect to membership in said association as a condition

of continued employment; (3) refusing to continue plain

tiffs’ employment because they have refused to disclose

whether or not they are members of said association.”

(Emphasis added.) Plaintiffs’ case is based on the allega

tion that defendants acted in derogation of their rights

12a

under an unconstitutional State statute; and, upon that

allegation, a court of three judges was convened pursuant

to 28 L . S. C. A., Sections 2281 and 2284. When the cause

came on for hearing, the Court was informed that the plain

tiff Carmichael had withdrawn from the case.

Plaintiffs allege that defendants deprived them of con

stitutional rights in the enforcement of the State statute.

See Act No. 741, Acts and Joint Resolutions of the General

Assembly of South Carolina, 1956. Plaintiffs claim that

this statute is unconstitutional, in that defendants (a) re

quired them to file written applications for employment,

and (b) refused to re-employ them as school teachers when

they failed to complete and file applications for employ

ment on required forms. By their answer, defendants ad

mit that plaintiffs were not re-employed because they

failed to file completed application forms. They deny that

plaintiffs had a legal right to be employed as teachers; that

there was anything wrongful in their failure to re-employ

plaintiffs; or that they in any way acted in the enforce

ment of the cited State Statute.

I agree that “ [tjhere is no dispute as to the facts.”

And such being the case, it is essential that all of the es

tablished and uncontradicted facts be considered, and that

those “ facts” which are the product of guess or surmise be

eliminated.

Prior to the school year 1956-1957, all of the plaintiffs

had been employed as school teachers in the Elloree Train

ing School. They had no tenure. All teacher contracts

were entered into between the teachers and the school offi

cials for terms of nine or ten months (a single school year)

terminating at the close of each term. The practice in the

School District, one adopted many years prior to the en

actment of the challenged State statute, was for applicants

for employment or re-employment as teachers to submit

written applications to the Superintendent of Schools in

Appendix A

13a

the District. Prior to May, 1955, an application was not

required to be in any prescribed form and was usually a

letter addressed to the Superintendent. In May, 1955,

however, defendants instituted the practice of providing

applicants with printed forms for use in making applica

tions. These forms contained a variety of questions to be

answered by applicants pertaining to the applicant's per

sonal as well as professional qualifications. For the school

term 1955-1956, all applicants, including plaintiffs, com

pleted such forms and submitted them to the Superintend

ent. From the applications submitted, defendants selected

plaintiffs and others for employment for the school term

1955-1956. For the 1956-1957 school term defendants con

tinued providing a form application for employment as

teacher to any person requesting one. In essential detail

the form used in 1956-1957 was identical with the form

used in 1955-1956. Some of the plaintiffs submitted incom

plete applications which the Superintendent returned to

them for completion and filing. The plaintiffs never there

after filed applications for employment, whether completed

or not and, consequently, plaintiffs were not considered by

the defendant-trustees as applicants. Some of the plain

tiffs submitted so-called “ resignations” . Others were not

heard from again. Thereafter, all teaching positions at

the Elloree Training School for the current school term

were filled from among other negroes who did apply for

such employment. It is now proposed, as one may reason

ably surmise from all that has been said, that plaintiffs

wish the Court to turn the clock back to May, 1956, and

enjoin the defendants from refusing to consider plaintiffs

as applicants for teacher jobs.

As no plaintiff occupied the status of employee of the

School District for the 1956-1957 school term, having en

tered into no contract for that term, the mentioned ‘ ‘ resig

nations” were idle gestures. If they served any purpose

Appendix A

14a

at all, it was to inform defendants that the so-called re

signers were not seeking re-employment.

The evidence or, strictly speaking, the lack of it, leaves

in doubt which of the questions on the application form

plaintiffs were unwilling to answer. A form application,

which defendants admit is genuine, is attached to the com

plaint, but the applications submitted by plaintiffs and

which were returned to them for completion were not of

fered in evidence, although the plaintiffs presumably had

possession of them. The only testimony having any pos

sible bearing on the questions that plaintiffs were unwilling

to answer was supplied by the plaintiff Davis, who, pre

suming to speak for the others, stated that plaintiffs ob

jected to answering all questions on the form other than

those asking for “ professional information” . Viewing the

agreed form attached to the complaint in the light of this

statement, it would appear that plaintiffs at least left the

following questions unanswered:

“ Religious preference ................. Are you a mem

ber! ................. I f so, state church of which you

are a member ................. List any clubs, organiza

tions, or fraternities to which you belong..................

Do you belong to the NAACP ? ................. Does any

member of your immediate family belong to the

NAACP? ................. Do you support the NAACP

in any way (money or attendance at meetings)!

................. Do you favor integration of races in

schools?..................Are you satisfied with your work

and the schools as they are now maintained?

Y e s ................. N o ..................... If yes, comment on

Back. Do you feel that you would be happy in an

integrated school system, knowing that the parents

and students do not favor this system? Y e s ..............

N o .............. (Check one and give reason for your

answer) ................. Do you feel that an integrated

Appendix A

15a

school system would better fit the colored race for

their life ’s work? Yes .......... No ..................

(check one and give reason for your answer) ..........

Do you think that you are qualified to teach an in

tegrated class in a satisfactory manner? Y e s .........

No .......... (check one and give reason for your

answer) ......... Do you feel that the parents

of your school know that no public schools will be

operated if they are integrated?' Yes ...............

No ................. Do you believe in the aims of the

N A A ( I P ? ................. I f you should join the NAACP

while employed in this school, please notify the

superintendent and the chairman of the board of

trustees. Y e s ................. N o ....................Do you de

sire a position in the Elloree Training School for

the 1956-1957 session?”

Plaintiffs contend that defendants’ refusal to accept

their incomplete applications for employment denied them

rights, privileges, immunities, due process of law and the

equal protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution, and that the challenged

statute, as to them, constitute a bill of attainder proscribed

by Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 of the Constitution.

The record in this case does not bear out the assump

tion that defendants acted under the challenged statute.

Hence the issue of the statute’s constitutionality is not

properly before the Court. Section 1 of the statute makes

unlawful the employment of a member of the National As-

sociation for the Advancement of Colored People by a

school district, and further provides that the prohibition

against such employment shall continue so long as mem

bership in such organization is maintained. There is an

utter failure of evidence that plaintiffs were refused em

ployment because of membership in any organization. In

deed, so far as the record discloses, only the plaintiff Ful

Appendix A

16a

ton is in fact a member of the NAACP, and she testified

that she never told any of the defendants that she was a

member; and there is no evidence that any of the defend

ants otherwise knew that she was a member. Hence, it is

ridiculous to say that defendants were enforcing Section 1

of the statute in refusing to employ plaintiffs as teachers

The best that can be said of this frivolous contention is

that one might, if he was so disposed, surmise that defend

ants would have denied plaintiffs employment if the es

sential facts upon which to rest such action had existed

elsewhere than in the imaginations of the plaintiffs.

Section 2 of the statute reads as follows:

“ Section 2. The hoard of trustees of any public

school or State supported college shall he authorised

to demand of any teacher or other employee of the

school, who is suspected of being a member of the

National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, that he submit to the board a written

statement under oath setting forth whether or not

he is a member of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, and the immediate

employer of any employee of the State or of any

county or municipality thereof is similarly author

ized in the case any employee is suspected of being

a member of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People. Any person refusing

to submit a statement as provided herein, shall he

summarily dismissed.” (Emphasis added.)

It is apparent that section 2 applies only to employees,

not to one who wants to be an employee, and the penalty

authorized by the section is dismissal. The section, there

fore, could have had no application to plaintiffs. No plain

tiff was an “ employee” of the Elloree Training School for

the 1956-1957 school term with which we are here con-

Appendix A

17a

eerned; and no plaintiff was “ dismissed”. They simply

declined to become applicants for employment, and, in

consequence of their failure to do so they were not em

ployed. It is a distortion to classify plaintiffs as

“ employees” . They were not employees at any tithe here

relevant; and the ipse dixit of this Court cannot make them

such. The practice of defendants in providing form appli

cations for the use of those desiring employment as teach

ers for the 1956-1957 school term was nothing more than

a continuation of the previous year’s practice, which was

not objected to by plaintiffs then. To say now that de

fendants adopted the application form as a means to the

enforcement of the challenged statute would be to deal

carelessly with the truth. It is an unchallenged fact that

the adoption of the application form antedated the statute

by ten months. Thus there is a total failure of evidence

to support the jurisdiction of this Court.

Section 2281, Title 28 USCA, is as follows:

“ An interlocutory or permanent injunction restrain

ing the enforcement, operation or execution of any

State statute by restraining the action of any officer

of such State in the enforcement or execution of such

statute or of an order made by an administrative

board or commission acting under State statutes,

shall not be granted by any district court or judge

thereof upon the ground of the unconstitutionality

of such statute unless the application therefor is

heard and determined by a district court of three

judges under section 2284 of this title.” (Emphasis

added.)

As pointed out, plaintiffs were not in such a position

that the defendants could have enforced the statute against

them had they wanted to do so. The cited jurisdictional

section does not give, nor was it intended to give, this

Appendix A

18a

Court jurisdiction to pass upon the constitutionality of a

State statute simply because some person here, or else

where, might be dissatisfied with its terms. Before a per

son can properly invoke the jurisdiction of a three-judge

Court to hear an attack on the constitutionality of State

statute, such person must not only allege, he must prove

that the statute has been wrongfully enforced against him

to his detriment, or that there is an impending threat to

enforce it against him to his detriment. Otherwise, he has

no right to vindicate and no interest to protect. Moreover,

to claim the protection of a court of equity, a person must

allege and prove that no legal remedy is available to him

and that he will suffer irreparable injury if a court of

equity does not grant relief.

_ As has been pointed out, on the authority of Cohens v.

Virginia, 6 Wheaton 264, 404, “ We have no more right to

decline the exercise of jurisdiction which is given, than to

usurp that which is not given.” We are here concerned

with the last of the two propositions; and I must decline to

become a party to usurping power which this Court legally

does not have. I also must refuse to classify the issues of

the instant case as falling within the comprehension of the

constitutional guarantees of the freedoms of speech and

assembly, as claimed by plaintiffs. No plaintiff has testi

fied in this case that the defendants have denied him or

any of the others the right of free speech, or the right of

free assembly; nor has any other witness done so. This

Court, therefore, is without evidence of a denial of the

lights of free speech and of free assembly; and clearly it

has no right by tortuous deductions or unfounded assump

tions to supply a seeming basis for such an issue.

The leal issue in this case is whether or not public

school authorities, acting on their own initiative, are con

stitutionally forbidden to inquire of applicants for teach

ing positions eoncernng their associations and beliefs.

Appendix A

19a

This case in many respects is similar to Garner v. Board of

Public Works of Los Angeles, 341 U. S. 716, 720, where

one of the issnes before the Court was stated as follows:

“ 1. The affidavit raises the issue whether the

City of Los Angeles is constitutionally forbidden to

require that its employees disclose their past or

present membership in the Communist Party or the

Communist Political Association. Not before ns is

the question whether the city may determine that an

employee’s disclosure of such political affiliation jus

tifies his discharge.”

Because of the admitted factual background of the in

stant case, there could not have arisen the issue of what

the Court would do if defendants had in fact discharged

plaintiffs because of membership in the NAACP. To the

knowledge of defendants no plaintiff was a member and,

therefore, no one of them could have been discharged for

that reason.

The answer to the stated issue was given by the Court

as follows:

“ We think that a municipal employer is not disabled

because it is an agency of the State from inquiring of

its employees as to matters that may prove relevant

to their fitness and suitability for the public service.

Past conduct may well relate to present fitness; past

loyalty may have a reasonable relationship to pres

ent and future trust. Both are commonly inquired

into in determining fitness for both high and low

positions in private industry and are not less rele

vant in public employment. The affidavit require

ment is valid.” 341 IT. S. at 720.

This position was reaffirmed in Adler v. Board of Edu

cation of the City of New York, 342 TJ. S. 485, 493, a case

Appendix A

20a

even more closely in point than the Garner case. There

the Court said:

“ We adhere to that case [Garner v. Board of Public

Works of Los Angeles, supra]. A teacher works in

a sensitive area in a school room. There he shapes

the attitude of young minds toward the society in

which they live. In this, the state has a vital con

cern. It must preserve the integrity of the schools.

That the school authorities have the right and duty

to screen the officials, teachers, and employees as

to their fitness to maintain the integrity of the

schools as a part of ordered society, cannot be

doubted. One’s associates, past and present, as well

as one’s conduct, may properly be considered in de

termining fitness and loyalty. From time immemorial

one’s reputation has been determined in part by

the company he keeps. In the employment of offi

cials and teachers of the school system, the state

may very properly inquire into the company they

keep, and we know of no rule, constitutional or oth

erwise, that prevents the state, when determining

the fitness and loyalty of such persons, from con

sidering the organizations and persons with whom

they associate.”

The Garner and Adler eases cannot be distinguished in