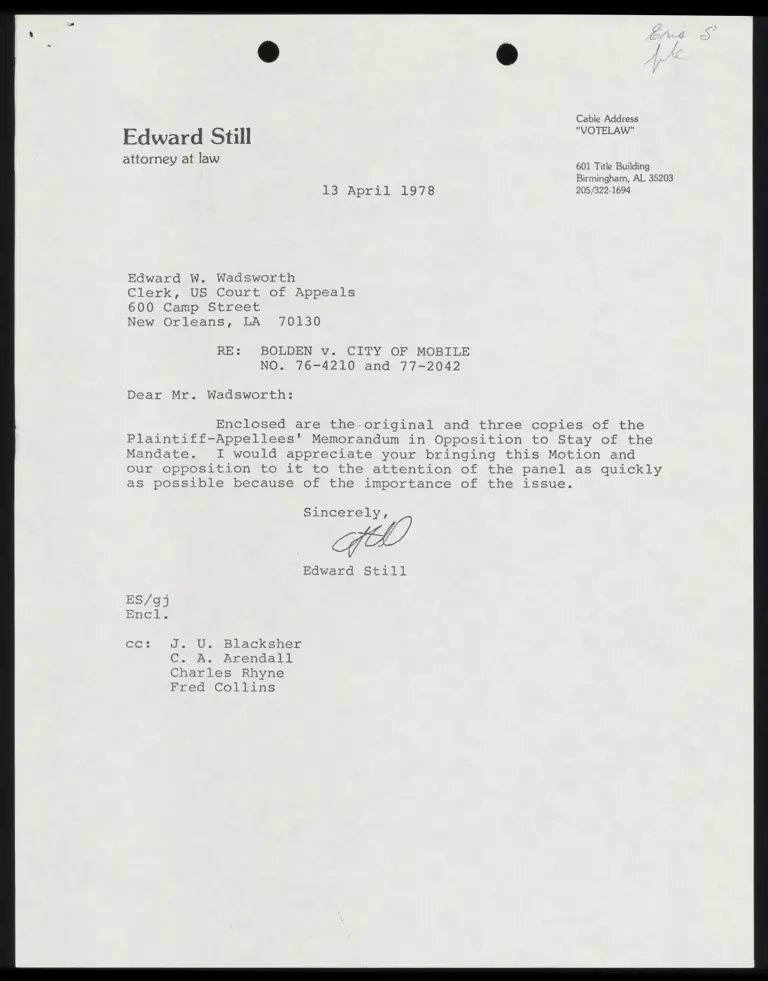

Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Motion for Stay of Mandate with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

April 13, 1978

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Motion for Stay of Mandate with Cover Letter, 1978. abab37eb-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/787cbe43-0e3d-4ad2-8b31-6a8edd4fd270/plaintiffs-memorandum-in-opposition-to-motion-for-stay-of-mandate-with-cover-letter. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

Cable Address

Edward Still “VOTELAW”

aiiorney at law 601 Title Building

Birmingham, AL 35203

13 April 1978 205/322-1694

Edward W. Wadsworth

Clerk, US Court of Appeals

600 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

IBF: BOLDEN v. CITY OF MOBILE

NO. 76-4210 and 77-2042

Dear Mr. Wadsworth:

Enclosed are the original and three copies of the

Plaintiff-Appellees' Memorandum in Opposition to Stay of the

Mandate. I would appreciate your bringing this Motion and

our opposition to it to the attention of the panel as quickly

as possible because of the importance of the issue.

Sincerely,

oy /

f/

/

Edward Still

ES/g9j

Encl.

CC: J." UU, Blacksher

C. A. Arendall

Charles Rhyne

Fred Collins

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-4210

NO. 77-2042

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al,

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

VS.

CITY OF MOBILE, et al,

DEFENDANT-APPELLANTS

MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION

FOR STAY OF MANDATE

Delay Favors the Incumbents

A stay of the mandate is not necessary to allow the

City Commissioners to seek a writ of certiorari before the

special election for a city council that will be ordered by

the Digtrict Court. In fact, the stay will serve only the

interests of the City Commissioners, and not the interests

of the white or black citizens of Mobile.

A brief review of the origin of the present stay is

helpful in understanding the Commissioner's request for a

further stay. After the District Court entered its order

requiring the city of Mobile to reorganize its government

into a mayor-council form, the City Commissioners appealed

and asked for a stay of the injunction. The District Court

entered a stay of its injunction under F.R.Civ.P. 62{(c).

The practical effect of this stay was to allow a regularly

scheduled at-large city commission election to occur in

August 1977. The Plaintiffs-Appellees moved this Court to

dissolve the District Court stay so that a city council

election would be held in August under the District Court

order or, in the alternative, to stay all elections pending

a resolution of the appeal 1/. The Court chose the latter

alternative and the City Commissioners, whose terms would

have ended on the first Monday in October 1977, have been

continued in office for 6 months beyond their normal terms

by this Court's order.

If the Commission takes the full 90 days 2/ allowed to

seek certiorari (and they indicate they will, Motion for

Stay of Mandate at 4), their petition for writ of certiorari

will not be filed until 28 June. Even ignoring the time

necessary for the Plaintiffs-Appellees to respond to the

petition, the Supreme Court will have no time to consider

the petition because it generally ceases to hold conferences

on cases in mid-June. The petition would be held until the

October Term began and the stay granted by this Court would

remain in effect. FRAP 41.

l/s he considerations which led this Court to grant

the stay of all elections no longer exist. Between the time

of the District Court opinion (22 Oct. 1976) and the order

staying elections (13 June 1977), Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp, 429 US 252 (1977),

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 US 144 (1977), and

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert. denied 98 S.Ct. 512 (1977), had been decided.

This court could rightly feel that it should review the

complex facts and law of this case in light of these intervening

decisions. The City Commissioners can point to no such

intervening decisions now which cast doubt on the validity

of this Court's decision.

2/: FRAP 41(b) provides: "The stay [of the mandate]

shall not exceed 30 days unless the period is extended for

cause shown." No such cause has been shown.

Thus a stay of 90 days will assure the Commissioners of

tenure unitl January 1979, even if they are denied the writ

of certiorari 3/.

On the other hand, the denial of the stay will encourage

the City Commissioners to file their petition with dispatch.

The Commissioners could submit their petition by the end of

April, the plaintiffs could reply by mid-May, and the Supreme

Court could consider the petition in late May or early June.

This would still be sufficient time to stay the election if

the Supreme Court felt it was warranted. Plaintiffs—-Appellees

will suggest to the District Court that the election be held

on 5 September (the date of the primaries) to avoid the

expense of a special election. If the District Court

chooses that date, qualifications for mayor and council

positions would be open from 15 June till 25 July.

The City Commissioners are trying to delay the inevitable.

Their interest thus conflicts with that of the City's residents

who are being denied their state statutory right to elect a

city government every four years. The black residents have

an even stronger interest in expeditious elections because

they have been denied access to the political process for so

long.

3/: If the Supreme Court denied certiorari on 2 October

(the first Monday), an election could not be held for 82 days

at a minimum, under the procedure established by the District

Court order. This would put the election two days before

Christmas, 1978. This does not take into account the delay caused

by a motion for reconsideration in the Supreme Court.

Mootness and Irreparable Harm

The City Commissioners allege that the case will become

moot if an election of the new city council is held. Motion

For Stay of Mandate at 2-3. In numerous cases, this Court

and the Supreme Court have set aside elections improperly

held, e.g. Hadnott v. Amos, 394 US 358 (1969); City of Phoenix

Vv. Kolodziejski, 399 US 204 (1970); Hamer v. Campbell, 358

F.24 215 {5th Cir. 1966), cert. denied 385 US 851 (1966);

Bell v. Southwell, 376 F.24 659 (5th Cir. 1967). Even if

they chose to do so, the newly-elected City Council could

not moot the lawsuit. There are four defendants: the City,

and its three commissioners sued "individually and in their

official capacities," Appendix at 1. The The individual

defendants continue to confuse themselves with "the City."

This "don't-moot-our-suit" argument is a variation on

the theme of continuing the Commissioners in office. Suppose

this Court had not granted a stay of election or had dissolved

the District Court stay and the whole City Commission campaign

had revolved around whether to continue to spend money on

the appeal. Could the incumbents have sought an injunction

to prevent the election because the election of at least two

commissioners who wanted to drop the appeal would "moot the

suit"? If the City Commissioners are so sure they embody

"the City," why are they afraid that a democraticly chosen

City Council will not likewise effect the will of the people

(as expressed in September 1978) 7?

A decision by a City Council to drop the appeal on

behalf of the City of Mobile would leave the three Commissioners

in the same position as the plaintiffs: without public

funds to pursue the appeal. The prospect of a lack of

monetary support from the public purse has not deterred at

least one of the Commissioners from vowing his desire to

continue the appeal 4/.

The sole basis for the Commissioners' contention that

an irreparable harm will befall the City of Mobile is Justice

Powell's stay order in Wise v. Lipscomb, 98 S.Ct. 15 (1977).

We submit that Justice's Powell's concern in Wise was not so

much the irreparable harm to Dallas but what he perceived as

a clear violation of Supreme Court precedents. 98 S.Ct. at

17-18.

The usual test applied by a Supreme Court Justice when

considering an application for a stay is a two-part one:

the likelihood of four Justices granting certiorari (or

agreeing to hear the appeal) and the irreparable harm that

can be done absent a stay. In cases in which the opinion

below 1s not perceived in such sharp discord with Supreme Court

precendents, elections following reapportionment have not

taken on such an "irreparable" character.

4/: In response to the question whether he would

continue the appeal if he were not in office, Lambert Mims,

one of the Mobile City Commissioners, answered that "his

convictions would be the same. In or out of office Mims

said he would still feel U.S. Judge Virgil Pittman's decree

was unconstitutional because the judge assumed legislative

responsibility." Mobile Register, 12 April 1978, page 1,

section B.

In Mahan v. Howell, 404 US 1201 (1971) (Black, Acting

Circuit Justice), Justice Black held,

The case is difficult; the facts are complicated; the

four district judges [on two three-judge courts] deciding

the case had no difficulty in reaching their conclucion

on the constitutional questions or in devising a plan

to correct the deficiencies found; the delay incident

to review might further postpone important elections to

be held in the State of Virginia should the stay be

granted.

In Graves v. Barnes, 405 US 1201 (1972) (Powell, Circuit Judge),

Justice Powell first decided that review was unlikely 5/, and

then never mentioned the "irreparable harm" of legislative

elections. In fact, there is more danger of irreparable change

when reapportioning a state legislature than a city government.

A court-reapportioned legislature can repeal the old law under

which their predecessors were apportioned and thus grant the

plaintiffs the victory they sought even if the Supreme Court

reverses. See, e.g., Sims v. Frink, 208 F.Supp. 431 (MD Ala.

1962) (three-judge court), aff'd sub nom Reynolds v. Sims, 377

US 533 (1964), in which the District Court was interested in

breaking the strangle-hold of the small counties by its order

so that the legislature could reapportion itslef. The City

Council of Mobile could do no more than propose a referendum to

the voters to select or reject a commission form of government.

5/: Of course, he was wrong. White v. Regester, 412

Us 755 (1973).

It could not call a referendum on the adoption of a different

form of mayor-council government because there is no statute

allowing such a referendum 6/. Thus there is no chance that

the new city council could moot the lawsuit by adopting an

ordinance.

The Commissioners' Rehashed Arguments

The facts and the law have been explicated in briefs,

reply briefs, supplemental briefs, and amicus briefs, not to

mention the arguments and briefs of the parties in the

companion cases. Despite the thorough opinion of the District

Court and the detailed examination of the facts by this

Court and the quartet of opinions outlining the law, the

City Commissioners seek to replow the same ground. Their

Motion for Stay of Mandate and the supporting Memorandum

offer the same arguments the Court found "unpersuasive."

Bolden, ms. 1.

The Commissioners contend that blacks enjoy a

vote in city elections -- and cite their own brief as authority.

Memorandum at. 3. Yet the District Court found that blacks'

success at electing favorable white candidates was precarious

because too-obvious black support would cause a white backlash.

Appendix 39.

Next the Commissioners accuse the Court of equating the

"difficulty of black voters in electing black officials with

6/: There is no statute allowing the mayor-councel

form to be adopted. Instead, all cities start out with

mayor-council form, Ala. Code, §11-43-40 (1975), and may

adopt a commission form. The only way to "adopt" the mayor-

council form is to "abandon" the commission form, Ala. Code,

§§ 11-44-150 et seq (1975), which means that the City must

have a commission form at the time of the referendum.

6

I

the existence of a constitution violation," Memorandum at 3,

when this Court actually held, "Although the failure of

black candidates because of polarized voting is not sufficient

to invalidate a plan, *** jt is an indication of lack of

access to the political processes." Bolden, ms. 6. The

Commissioners continue the tactic they used in their first

briefs: to take each componet of proof and announce it is

insufficient and ignore the "aggregate."

The Commissioners attack the Court's requirement of

intent -- not because the Court did not require proof of

intent but because the Court did not require proof of initial

intent. This is the same "immaculate conception" argument

they made in their brief and that the Court rejected.

Bolden, ms. 11-13.

The Commissioners state "the District Court below did

not [hold] that proof of invidious racial purpose is an

essential element of proof in voting dilution cases," Motion

at 3. This Court noted in its opinion that it was affirming

the District Court's finding of intent in the maintenance of

the racially discriminatory form of city government. Bolden,

ns. 12.

At base, the Commissioners are really arguing that the

City of Mobile's system of government is immune from constitutional

attack because the Court's order "would have required not

merely redistricting but a complete restructing of Mobile's

existing system of government," Memorandum at 6. The

Commissioners emphasize the change in the form of government

that will take place and forget the oft-gquoted dictum, "The

[Fifteenth] Amendment nullifies sophisticated as well as

simple-minded modes of discrimination," Lane v. Wilson, 307

US 268 (1939), which is equally applicable to the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Court has already considered and rejected

this argument. Bolden, ms. 13-14.

Every factual and legal argument the Commissioners make

in their Motion has been made to, and rejected by, this

Court.

Likelihood of Certiorari

The City Commissioners argue that the Supreme Court is

likely to grant a writ of certiorari because (a) this Court

and the District Court were wrong about the facts; (b) this

Court and the District Court were wrong on the law of proof

Of intent; and (c) this is an important case involving

"every local government with the need or traditional preference

for at-large elections," Memorandum in Support of Motion for

Stay of Mandate at 6. If the doom of the commission form is

sealed by Bolden, why did this Court remand BULL v. Shreveport?

The position of the City Commissioners seems to be that

the Supreme Court will grant certiorari because "the Supreme

Court has recently found it necessary to accept numerous

cases turning upon this important issue [intent] ," Motion

for Stay of Mandate at 3-4. Just because the Supreme Court

has previously heard or remanded cases in which intent was

not considered by the courts below that is no sign that the

Supreme Court will grant certiorari to hear a case in

which proof of intent was required by this Court. The mere

invocation of Washington v. Davis, 426 US 229 (1976), has

not moved the Supreme Court to grant certiorari in the

following cases in which the Court of Appeals had utilized

an intent standard to test the sufficiency of the evidence:

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F.2d 1042 (6th Cir.

1977), cert. denied 98 S.Ct. 631 (1977); United States v. School

District Of Omaha, 541 F.28 708 (8th Cir. 1976), vac. and

remanded 97 S.Ct. 2905 (1977), reconsidered 565 F.2d 127

(8th Cir. 1977), cert. denied 46 USLW 3526 (21 Feb. 1978);

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied 98 S.Ct. 512 (1977); and Harkless v. Sweeney

Independent School District, 554 F.24 1353 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied 98 S.Ct. 508 (1977).

Washington v. Davis is not the "open sesame" to the

doors of the Supreme Court. We submit that the Supreme

Court 1s not likely to grant certiorari to review this

Court's holding in this case.

As noted above, the City Commissioners are arguing that

the Court below or this Court made incorrect factual findings.

The Supreme Court is not going to "grant a certiorai to

review evidence and discuss specific facts," United States v.

Johnston, 268 US 220, 227 (1925), especially "to review

concurrent findings of fact by two courts below in the

absence of a very obvious and exceptional showing of error."

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 336 US

271,:275 (1949).

Conclusion

The best way for this Court to insure that the City

Commissioners are expeditious in submitting their petition

for certiorari is to deny the Stay of the Mandate. There is

ample time for both sides to brief the questions involved in

the certiorari petition before the Supreme Court recesses.

Then if certiorari is denied, single-member district elections

can be held in September. On the other hand, if a stay is

granted, the Commissioners will have no incentive to expedite

their petition, the Supreme Court will not be able to consider

the petition before October, and the incumbent, unconstitutionally-

elected officials will be retained in office until next

year.

Alternatively, 1f the Court decides to grant a stay,

plaintiffs urge it be limited to 30 days with no extensions.

ray 24 4

Sr AW = a

EDWA RD STILL

601 Title Building

Birmingham, AL 35203

J. U. Blacksher

Larry Menefee

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, AL 36603

Jack Greenberg

Eric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, NY 10019

10

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, the undersigned attorney, do hereby certify that,

prior to or immediately after filing the foregoing with the

Court, I mailed or delivered a copy to the following:

Charles A. Arendall, William C. Tidwell, III, Travis M.

Bedsole, Jr., P. 0. Box 123, Mobile, AL 36602,

Charles S. Rhyne, William W. Rhyne, Donald A. Carr,

Martin W. Matzen, Suite 800, 1000 Connecticut Avenue,

NW, Washington, DC 20036, Fred Collins, City Attorney,

City Hall, Mobile, AL 36602. 2

DATE: / 3 Apnid [57% AY

7 OF COUNSEL

11