Copeland v. Marshall Memorandum Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees' Motion for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Copeland v. Marshall Memorandum Amicus Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees' Motion for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, 1977. a4d27560-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/78a67d6e-00b0-4fc5-beff-757c4a605205/copeland-v-marshall-memorandum-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellees-motion-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

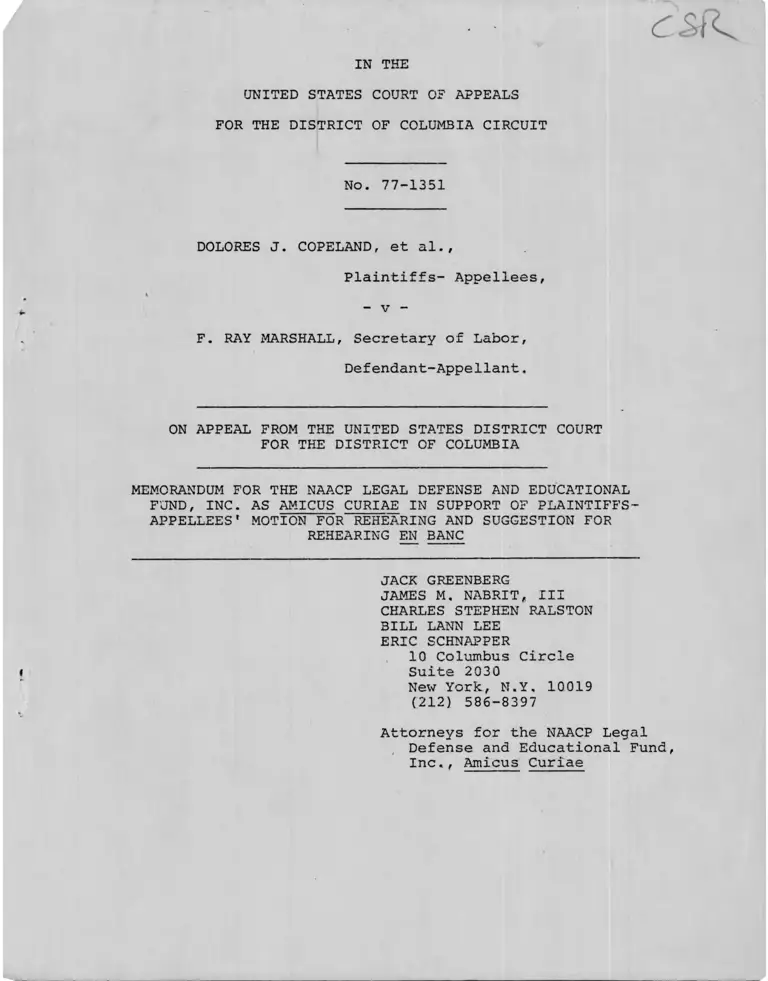

IN THE

esK

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 77-1351

DOLORES J. COPELAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs- Appellees,

- v -

F. RAY MARSHALL, Secretary of Labor,

Defendant-Appellant,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

MEMORANDUM FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-

APPELLEES' MOTION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION FOR

REHEARING EN BANC

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y, 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc,, Amicus Curiae

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 77-1351

DOLORES J. COPELAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

- v -

F. RAY MARSHALL, Secretary of Labor,

Defendant-Appellant.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE

ON BEHALF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

AND MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. Amicus Curiae

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 77-1351

DOLORES J. COPELAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

- v -

F. RAY MARSHALL, Secretary of Labor,

Defendant-Appellant.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE MEMORANDUM AMICUS CURIAE

ON BEHALF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

respectfully moves the court, pursuant to Rule 29 F.R.A. Proc.

for permission to file the attached Memorandum amicus curiae,

for the following reasons. The reasons assigned also disclose

the interest of the amicus.

(1) Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York in 1939. It

was formed to assist Blacks to secure their constitu

tional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its

charter declares that its purposes includes rendering

i

legal aid gratuitously to Blacks suffering injustice

by reason of race who are unable, on account of pov

erty, to employ legal counsel on their own behalf.

The charter was approved by a New York Court, author

izing the organization to serve as a legal aid society.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF)

is independent of other organizations and is supported

by contributions from the public. For many years its

attorneys have represented parties and has participated

as amicus curiae in the federal courts in cases involv

ing many facets of the law.

(2) Attorneys employed by movant have represented

plaintiffs in many cases arising under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, e,g., McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) ; Albemarle Paper

Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). They have appeared before

this Court in a variety of Title VII cases involving

agencies of the federal government both as counsel for

plaintiffs, e.g., Foster v. Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C

Cir. 1977), and as amicus curiae, Hackley v. Roudebush,

520 F. 2d 108 (D.C. Cir. 1975) .

(3) Amicus has also participated in many of the

leading cases involving attorneys' fees questions, both

-2-

a counsel, e'.g., Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises , 390 U.S. 400 (1968); Bradley v. School

Board of the City of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974);

Hutto v. Finney, ___U.S._____, 57 L.Ed 2d 522 (1978) ;

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express Co., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974); Foster v. Boorstin, supra; and as

amicus curiae, e.g., Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

Equal Employment Opportunity Comm., 434 U.S. 412

(1978). In addition we have prepared and litigated

counsel fee applications in numerous other cases

arising under the various civil rights laws. In

these cases we have been associated with private

members of the civil rights bar, most of whom are

with small firms (up to 10 lawyers) or are single

practitioners. Therefore, we believe that our views

on the practical impact of the decision in this case

on civil rights practitioners will be helpful to the

Court in determining whether a rehearing or rehearing

en banc should be granted.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons amicus moves that

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. be given leave to

file the attached memorandum amicus- curiae.

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

(212)586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

INDEX

Page

Introduction ............................................... 1

I. THE PANEL DECISION'S STANDARDS FOR CALCULATING

ATTORNEY'S FEES ARE INCONSISTENT WITH THE ACT'S

PURPOSE OF ENCOURAGING CIVIL RIGHTS LITIGATION . . 2

II. THE PANEL DECISION CONFLICTS WITH THE DECISION

IN EVANS V. SHERATON PARK HOTEL AND DECISIONS

OF THE SUPREME COURT AND OTHER CIRCUITS ........ 6

Conclusion ....................................... . . . . . 10

Certificate of Service.................. ..................11

CITATIONS

Cases:

Bell v. Brown, 557 F.2d 849 (D.C. Cir. 1977) . . . . . 7

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425 U.S,

820 (1977).............. .................... .. . 7

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1977).......... 7

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) 7

Copeland v. Usery, 13 E.P.D. 1[ 11,434 (D.D.C. 1976) . . 8

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1[ 94 4 4

(C.D. Cal. 1974)...................................9

Day v. Matthews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976) . . . 7, 8

Evans v. Sheraton Park Hotel, 503 F.2d 177 (D.C. Cir,

1974).......................................2, 5, 6, 9

Foster v. Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977) . . . 7

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir, 1975) . . . . 7

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108 (D.C, Cir. 1975) . , 7

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express Co,, 488 F.2d 714

C5th Cir. 1974)........ .. , 3, 5, 9

i

Cases-continued page

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 32Q (JD,C, Cir, 19.771 , ,8, 9

Sperling v. United States, 515 F,2d 465 (3rd Cir,

1975)..................................... .. , , 8

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal.1974)........................................... 9

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975) .................... 9

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1 * 8 8 ................... 9

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(d) 6

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) - C k ) ......................... 7

Miscellaneous;

94th Cong. 2d Sess. 6 (1976).................... .. , 9

S. Rep. No. 94-1011............................ .. . 9

U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News, 1976 Vol. 5, p. 5913 . 9

li

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 77-1351

DOLORES J. COPELAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

F. RAY MARSHALL, Secretary of Labor,

De fendant-Appe1lant.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

MEMORANDUM FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-

APPELLEES' MOTION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION FOR

REHEARING EN BANC

Introduction

This Memorandum amicus curiae is filed by the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., in support of the motion of

plaintiffs—appellees Dolores J. Copeland, et al., for rehearing

and suggestion for rehearing en banc from the panel opinion of

October 30, 1978. We urge that the panel opinion establishes

special "standards and procedures to be followed in awarding

attorney's fees to a party prevailing in litigation against an

agency or department of the United States under the employment

discrimination provisions of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964," slip opinion at p. 2, that are inconsistent with the

governing standards previously established for the award of

reasonable attorney's fees in this Circuit by Evans v. Sheraton

Park Hotel. 503 F.2d 177, 186-189 (D.C. Cir. 1974). In Part II

of this Memorandum we will outline the reasons why we believe

the panel opinion is erroneous as a matter of law. First, how

ever, we wish to discuss the practical effects of the decision

on civil rights practitioners.

I.

THE PANEL DECISION'S STANDARDS FOR CALCULATING

ATTORNEY'S FEES ARE INCONSISTENT WITH THE ACT^S

PURPOSE OF ENCOURAGING CIVIL RIGHTS

__________________ LITIGATION__________________

As set out in the motion for leave to file this memorandum,

the Legal Defense Fund has been involved in Title VII litigation

and in cases involving counsel fees under various civil rights

statutes since 1965. In all of its cases the Fund works with co

operating attorneys who serve as local and lead counsel. These

attorneys, both in the District of Columbia and nationwide, are

1/predominantly single practitioners or practitioners in small firms.

The application of the standards set out in the panel decision to

organizations such as the Legal Defense Fund and to the attorneys

on whom it relies will penalize the very persons whose efforts

Congress meant to encourage when it enacted the attorney's fees

provision.

_l/ The examples given in this Memorandum are based on our experiences

with such practitioners.

2

The problem with the formula described in the panel de

cision is that it would result in fees that would be determined

by the type of law practice that happened to be carried on by

plaintiffs' attorneys, and not by the nature, quality, or value

of the legal work done. Thus, a large firm, with the high over

head, large salaries, and profit margin typical of such a practice,

would receive large fees. A solo practitioner whose practice is

entirely or predominantly civil rights, and who thereby may have

particular expertise in such cases, on the other hand, would re

ceive diminished fees for a number of reasons.

First, the formula does not take account of the contingent

nature of civil rights litigation. Compare, Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714, 718 (5th Cir. 1974). Unlike a

large firm having a varied commercial practice based substantially

on retainer agreements and a docket of matters which assures steady

income based on hourly rates or negotiated fixed fees, the civil

rights practitioner must in making calculations, include a signi

ficant contingency factor because of the risk of losing cases.

For example, a civil rights attorney may agree with a client upon

a fee of $75.00 per hour. But the client actually may be billed

at $20-$40 per hour, or not billed at all, because the client,

who is most likely at the GS-7 to GS-11 level, will not be able

to pay any more. Alternatively, a private civil rights practitioner

may obtain support, in the form of costs and a nominal fee, from

a civil rights organization. If the case is won, the attorney

expects to obtain the balance from a court reward. If the case

is lost, the attorney will never be paid fully. This fact affects

the hourly rate sought in cases that are won. Moreover, there is

usually a two to three-year (or longer) period from initially

3

undertaking the matter to final award of fees. Inflation, loss

of interest, costs of borrowing must be part of the calculation.

Second, the typical small practitioner operates on low

overhead. And, lacking long-term clients and retainers, such

an attorney must operate at a high level of efficiency. For the

fee to be dependent on overhead, therefore, would penalize economy

and efficiency. Conversely, if the panel decision were to be the

law, practitioners would be encouraged to increase overhead and

to spend more time on cases than they warrant.

Third, the concept of "reasonable" profit in the case of

a small civil-rights practitioner is inappropriate. There are no

commercial clients whose fee payments may be compared. On the

other hand,toalarge firm fees obtained in occasional civil rights

cases are such a small portion of total income that they will not

appreciably affect partners' shares or associates' salaries. But

if an experienced single practitioner grosses $50,000/year based

on an hourly rate of from $60-$75 per hour, and has expenses of

$20,000, the net will be $30,000. That amount is that person's

income — significantly less than that of an associate with com

parable experience in a large firm. Whether a "profit margin"

of 60% ($30,000 net from $50,000 gross) is "reasonable" is, there

fore, not a meaningful question in such circumstances. Should

the courts decide that such an attorney should be content with

$20,000 a year, or less, and discourage lawyers from engaging

in civil rights practice? What factors is a court to weigh when

it takes upon itself the task of deciding the appropriate income

level of an attorney who has dedicated his or her career to socially

valuable work? And should a court have that power at all?

4

The factors set out by the panel are no less inappropriate

and unworkable when applied to an organization such as the Legal

Defense Fund. Again, its overhead is significantly less than

than of a large law firm. As a charitable organization, the Fund

would be derelict in its duty to the public that supports it if

contributions were used for opulent surroundings. For the same

reason, staff salaries do not match those of large law firms. The

Fund does not make a profit in any sense of the word, so that there

is nothing that could be appropriately used for comparison purposes.

Thus, using the factors set out in the panel decision, the

Legal Defense Fund and similar organizations could receive fees

significantly below those which a large firm would. The attorneys

employed by such organizations, however, are expert and experienced

in Title VII, civil rights law, and federal court litigation.

In sum, the formula devised by the panel would have a

harmful impact on the portion of the bar with the greatest expertise

in civil rights litigation — civil rights organizations and the

civil rights bar that consists primarily of solo or small-firm

practitioners. The result would be to penalize and discourage

attorneys from pursuing a career in civil rights work, thereby under

mining the purpose of counsel fees legislated. For these reasons,

we urge that the Court should return to the Johnson-Evans approach

discussed below, viz, determine an hourly rate based on prevailing

rates in the community related to experience, expertise, and work

done in comparable types of litigation. Thus, fee awards would be

based on the appropriate considerations of quality and value of

work done and not on irrelevant factor of the type of practice

— large-firm, small-firm, or single-practitioner — the attorney

5

happens to be engaged in

THE PANEL DECISION CONFLICTS WITH THE DECISION IN EVANS

V. SHERATON PARK HOTEL AND DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME

_______________COURT AND OTHER CIRCUITS________________

II.

Amicus respectfully submits that the panel opinion erroneously

burdens private enforcement of Title VII. The holding that "the

considerations enumerated by this court in Evans v. Sheraton Park

Hotel for the determination of attorneys' fees in an action against

a private party are applicable generally to Title VII cases against

a federal agency, but that special caution must be shown by the trial

court in scrutinizing the claims of attorneys for fees against a

federal agency in such litigation" (emphasis added), slip opinion,

p. 12, in fact, results in an unprecedented rule which, contrary

to the panel's disavowal, "overburden[s plaintiffs and] the trial

court with the task of compiling and processing massive amounts of

billing data [and] set[s] a standard of proof in reporting charges

that is so high as to discourage attorneys from pursuing litigation

in the public interest," slip opinion, p. 20. More fundamentally

the purpose of an award to compensate plaintiffs as the prevailing

party for litigation expenses is completely frustrated by a rule

that makes the amount of an award turn not on the quantity and

quality of the legal representation, but on whether the defendant

is a federal agency.

First, the lesser right to recover attorney's fees as part

of the costs in federal employee Title VII cases violates express

2/statutory language that private Title VII standards govern and

2/ 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (d).

- 6 -

that "the United States shall be liable for costs the same as a

3/

private person" (emphasis added). This Court and the Supreme

Court have rejected claims by the government that federal employees

have lesser rights than private company and state or local govem-4/

ment employees under Title VII on a wide range of issues, and

5/

the rule for counsel fees should be no.different. Last term a

unanimous Supreme Court, in Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC.

434 U.S. 412 (1978), rejected just an effort to have a different

fees standard for government and private parties, in the context

of fees against a Title VII plaintiff party, for the very reason

asserted by the panel, i ,e., "the Government's greater ability

to pay adverse fee awards compared to a private litigant." After

discussing "equitable considerations on both sides of this question,

the Court ruled that:

3/ 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k).

4/ See, e .g.. Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975) (re

mand for administrative proceedings); Hackley v. Roudebush, 520

F.2d 108(1975)(trial de novo); Day v. Matthews. 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C.

Cir. 1976)(burden of proof standards); Bell v. Brown. 557 F.2d 849

(D.C. Cir. 1977)(timely filing of civil action); Foster v. Boorstin,

561 F .2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977)(prevailing party for award of attor

ney's fees). Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1977).

5/ The Supreme Court has ruled that " [s]ections 706 (f) through

(k), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) through 2000e-5(k), which are incor

porated 'as applicable' by §717(d), govern such issues as . . .

attorneys' fees," Brown v. General Services Administration, 425

U.S. 820, 832 (1977); See also, Foster v. Boorstin. supra, 561 F.2d

at 340, n. 1.

7

Yet §706 (k) explicitly provides that "the

Commission and the United States shall be liable

for costs the same as a private person." Hence,

although a district court may consider distinc

tions between the Commission and private plaintiffs

in determining the reasonableness of the Commission's

litigation efforts, we find no grounds for applying

a different general standard whenever the Commission

is the losing plaintiff."

434 U.S. at 423, n. 20 (emphasis added). This Court has also

noted that the application of a lesser standard in counsel fee

cases where a federal agency is the defendant is particularly

inappropriate since private litigation is the only means of en

forcing Title VII against the government. Parker v. Califano,

561 F.2d 320, 321 (D.C. Cir. 1977). Finally, the Attorney general

himself has disclaimed any argument that different standards should

' 6/

be applied to it in deciding an amount of attorney's fees*

6/ See, Memorandum For United States Attorneys and Agency General

Counsels, Re: Title VI Litigation. Aug. 31, 1977, p. 2;

In a similar vein, the Department will not urge

arguments that rely upon the unique role of the

Federal Government. For example, the Department

recognizes that the same kinds of relief should

be available against the Federal Government as

courts have found appropriate in private sector

cases, including imposition of affirmative action

plans, back pay and attorney's fees. See Copeland

v. Userv. 13 EPD 511,434 (D.D.C. 1976); Day v.

Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976); Sperling

v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3d Cir. 1975). Thus,

while the Department might oppose particular remedies

in a given case, it will not urge that different

standards be applied in cases against the Federal

Government than are applied in other cases.

8

Second, the restrictive standards are specifically

contrary to the standards developed by this Court in Evans v.

Sheraton Park Hotel, supra, and by other courts in order to------------------- 7/

promote private enforcement of Title VII in a line of cases

which Congress subsequently embraced in the Civil Rights

Attorney's Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.SC,§1988, see, Parker

v. Califano, 561 F.2d at 338. Thus, the Senate Report states

that:

It is intended that the amount of fees

awarded under [the Act] be governed by the

same standards which prevail in other types

of equally complex Federal litigation, such

as antitrust cases and not be reduced

because the rights involved may be nonpe-

cuniary in nature. The appropriate standards,

see Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488

• f .2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974), are correctly

applied in such cases as Stanford Daily v.

Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Davis

y. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1[ 9444

(C.D. Cal. 1974); and Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D, 483

(W.D.N.C. 1975)" These cases have resulted in

fees which are adequate to attract competent

counsel, but which do not produce windfalls to

attorneys. In computing the fee, counsel for

prevailing parties should be paid, as is tra

ditional with attorneys compensated by a fee

paying client, "for all time reasonably ex

pended on a matter." Davis, supra; Stanford

Daily, supra, at 684.

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 6 (1976), U.S. Code

Cong. & Admin. News, 1976, Vol. 5, p. 5913.

7/ e .g., Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F .2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974).

9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the panel decision should be

vacated and the decision of the district court affirmed.

Respectfully submitted

VCK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE and EDUCATIONAL FUND,

As Amicus Curiae INC .

10

P O K E R G A M E

V ♦ * A

Friday, April 18, 1997

285 St. Nicholas Avenue

Apt. 55

Food and Refreshments

Hosted by

OSCAR FAMBRO

8:00 p.m.

© © ©