Jinks v. Mays Brief for Defendants-Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jinks v. Mays Brief for Defendants-Appellees, 1972. b9a518fc-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/78fa795d-1287-465f-97da-2320701e9134/jinks-v-mays-brief-for-defendants-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

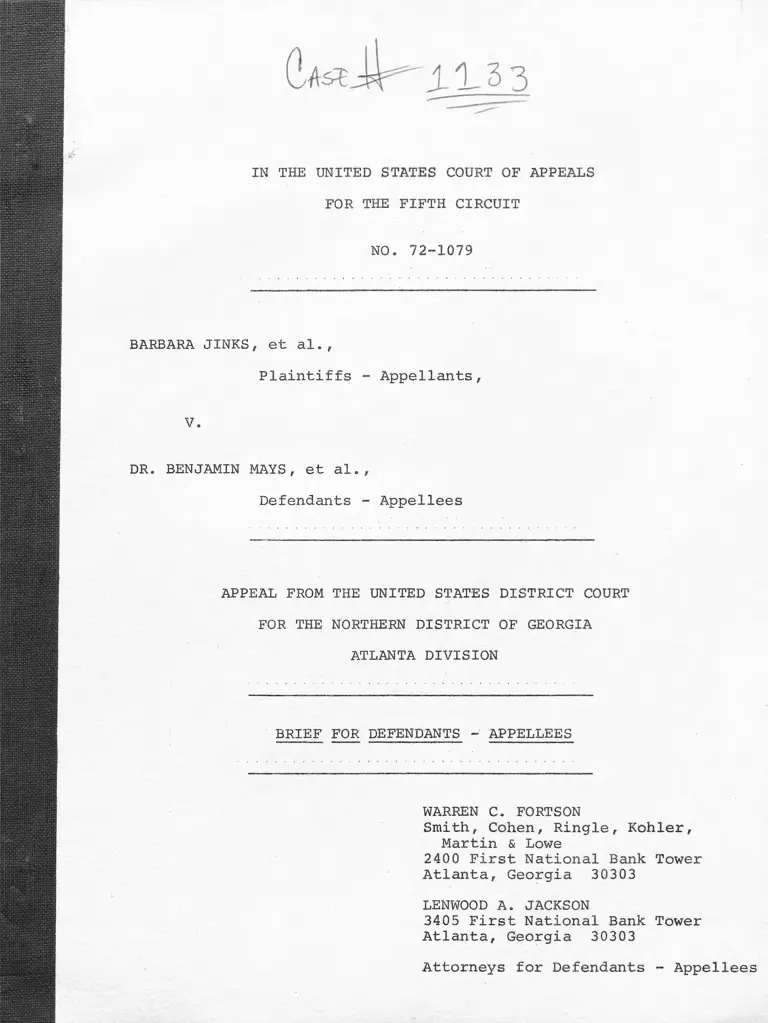

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-1079

BARBARA JINKS, et al.f

Plaintiffs - Appellants,

V.

DR. BENJAMIN MAYS, et al..

Defendants - Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ATLANTA DIVISION

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS - APPELLEES

WARREN C. FORTSON

Smith, Cohen, Ringle, Kohler,

Martin & Lowe

2400 First National Bank Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

LENWOOD A. JACKSON

3405 First National Bank Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Attorneys for Defendants - Appellees

I N D E X

Page

Subject Index:

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS 2

ARGUMENT 5

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Clark v . American' Marine' Corp. ,'

320 F. Sllpp. 709 (E.D. La. 1970)

aff’d per curiam 437 F .2d 959

(5th Cir. 1971) 15

Harkness v. Sweeny' independent' 'School' District,,

7£TTF .2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970) ~ ~ “ ‘ 11,12

Horton v'. Lawrence County Board of Education,

~ 449 F.2d"”9T7~'(5th Cir. 1971) “ " 11,12,16

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.,

444 F .2d 143, (5th Cir. 19 71) 15

McF'erren v. County School Board,

4 EPD 91-7652 10,11

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite' Co. ,

~ 3 9F15TsT~T7rTl9W 14,15

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,' The. ,

390 U.S. 400 (19687 ” 14

United States v1. Hayes International Corp. ,

4 FEP Cases 411 (5th Cir. 1972) 10

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. 1983 13,14

Miscellaneous:

6 Moore’s Federal Practice 1352 (1966 ed.) 15

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 72-1079

Barbara Jinks, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

V.

Dr. Benjamin Mays, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

On Appeal from The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Georgia

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiffs-Appellants filed this action in the

United States District Court for The Northern District of

Georgia, Atlanta Division, on July 22, 1970. On September

28, 1971, the District Court issued an order granting

Plaintiffs-Appellants' motion for summary judgment and ruling

that Defendants-Appellees! policy denying maternity leave

to nontenued teachers violated the Equal Protection Clause

of the United States Constitution. Plaintiffs-Appellants on

October 7, 1971, filed their motion to alter or amend, or in

the alternative to reconsider that portion of the District

Court's Order of September 28, 1971, denying appellant back

pay* The District Court, on November 3, 1971, denied

Plaintiffs-Appellants1 motion to alter or amend its order

of September 28, 1971, and Plaintiffs-Appellants have filed

this appeal seeking to recover back pay and reasonable

attorney’s fees.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The appellant, Barbara Jinks, is a married female,

who for three years was employed as a probationary teacher in

the Atlanta Public Schools. Sometime in the Spring of 1970,

she was offered a contract to continue teaching which she

accepted on May 28, 1970. On July 24, 1970, counsel for Mrs.

Jinks wrote to the principal of the school in which she had

been teaching to inform him that Mrs. Jinks was pregnant and

expected to deliver her child in October. The letter further

stated that "Mrs. Jinks has commenced a law suit in federal

court to compel the Board of Education to grant her and other

non-tenured teachers maternity leave, and looks forward to

rejoining you after the birth of her child." (A. 20a)

On July 28, 1970, Dr. John W. Letson, Superintendent

of Atlanta Public Schools, wrote counsel for Mrs. Jinks and

2.

informed him that since Mrs. Jinks was a probationary teacher

she was not eligible for maternity leave and that her employ

ment status would therefore be listed as "resigned". The

letter also stated that if following the delivery of her child,

Mrs. Jinks wished to return to a teaching position in the

Atlanta Public Schools, she should contact the personnel office

and request re-employment. The letter from Dr. Letson further

stated that Mrs. Jinks’ request for re-employment would be

given consideration in terms of the needs of the system at that

time. (A. 21a) Counsel for Mrs. Jinks was also informed that

even if Mrs. Jinks had been eligible for maternity leave, such

leave would not have assured her return to the same school.

(A. 21a).

According to Appellees' policy existing at that time,

non-tenured or probationary teachers who became pregnant, were

not eligible for maternity leave status. Probationary teachers,

who because of their pregnancy were required to take leave from

their position, were listed as having resigned. If, however,

their services in the past were satisfactory, their applications

for re-employment were given very careful consideration.

Probationary teachers re-elected after resignation for maternity

reasons were granted years of service and the previous status

enjoyed at the time of their resignation. (A. 35a)

3.

Appellees' policy existing at the time of this law

suit and its present policy with respect to teachers who have

attained tenure status is that they were and are eligible for

maternity leave status. (A. 35a) When a tenured teacher who

has taken the necessary steps to acquire maternity leave

status has given birth to her child and is ready to return to

work, she must notify the personnel office of her desire and

readiness to return to work. The personnel office will then

at the first opportunity find her a job in the system. A

tenured teacher is not guaranteed the same position or the

same school upon their return to the system since the ability

to place these returning teachers is based on the normal

turnover in personnel. (A. 120a)

Appellant, Barbara Jinks, brought this action on

her own behalf and on behalf of all those similarly situated

non-tenured female teachers alleging that Appellees' policy of

not granting maternity leaves to probationary teachers was

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The District Court found Appellees' policy to be

arbitrary and in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court, however, denied

Appellants' prayer for back pay on the ground that Appellant

failed to show that she had notified Appellees of her desire

to return to work and Appellees had refused to re-employ her.

4.

The Court did order that Appellant recover costs of the

action but did not award reasonable attorney's fees as

Appellant had requested.

ARGUMENT

I.

Appellant Is Not Entitled to Back Pay

Clearly, this is not a case in which back pay should

be awarded. The facts do not warrant the awarding of back pay

and the evidence does not establish Appellant's right to back

pay. Moreover, there simply is no basis for a determination

of any amount of back pay due.

The District Court's finding that Appellant had not

alleged in her complaint or in any of her responsive pleadings

that she attempted to return to the school system after her

pregnancy is well supported by the record and is definitely

not contrary to the evidence as Appellants assert. Appellants

erroneously interpret the District Court's decision as

denying Mrs. Jinks back pay because her responsive pleadings

did not allege that she wished to return to the school system

after her pregnancy. In its Order of September 27, 1971, the

District Court held:

"In her complaint plaintiff prayed for back

pay in case defendants refused to re-employ

her on the ground that her position had been

filled by a new employee. The Court has not

5.

been informed by plaintiff that this has

occurred and no facts have been presented

upon which this court might award back pay.

Plaintiff's prayer for back pay will there

fore be denied.” (A. p. 157a)

It is clear from reading this portion of the Court's

order that it was not based upon the failure of Appellant to

allege that she wished to return to the school system after her

pregnancy. The Court's order is based on the fact that there

is absolutely no evidence in the record or elsewhere that

Appellees refused to re-employ Appellant on the ground that

her position had been filled by a new employee.

Appellants go through great pain in their brief to

show that Mrs. Jinks evidenced an interest and expressed a

wish to return to the school system after her pregnancy. First

Appellants contend that the fact that Mrs. Jinks signed a

contract with Appellees for the 1970-71 school year showed that

she was interested and wished to return to the school system.

Next, Appellants rely on the letter dated July 24, 1970, in

which Mrs. Jinks, through counsel, stated that she "would

return to her teaching position after the child's birth."

(Appellants' Brief p. 5). Finally, Appellants rely on their

6.

answers to Appellees' first interrogatories in which Mrs.

Jinks stated that she would accept her position as a non-

tenured teacher for the 1970-71 school year as being evidence

of her interest to return to the school system. Conceding

that all these facts established an interest and desire on

Mrs. Jinks' part to return to the school system after the

birth of her child, the Appellant has still missed the issue

by a wide mark. The issue, as the District Court correctly

decided, was and is not whether Appellant evidenced an interest

or expressed a desire to return to the school system after the

birth of her child, but rather, whether Appellant attempted

to return to the school system and was refused.

The District Court's order of November 3, 1971,

states:

"Although her complaint prayed for back pay

in the event the court determined she was

entitled to maternity leave, plaintiff did

not allege in the complaint or in any of

her responsive pleadings that she attempted

to return to the school system after the

birth of her child and defendants refused

to rehire her. (A. 170a) (Emphasis supplied)

7.

It is very clear that the District Court did not

deny Appellant, bade pay because she failed to establish that

she had expressed an interest and desire to return to the

school system, but rather, because she did not allege and

the evidence does not establish that she attempted to return

to the school system and Appellees refused to hire her.

In this appeal and in their brief, Appellant is

apparently attempting to establish a special class in which

no one belongs except Mrs. Jinks. Not even tenured teachers

are entitled to pay during the time they are on maternity

leave. (A. 35a) Nor are they guaranteed immediate return

to the system the moment they decide that they are ready to

return. (A. 120a) Yet Appellant is demanding that she be

awarded pay during the time she was away from her job for

maternity reasons. Appellants could not possibly be demanding

back pay because there simply is no criterion upon which to

base such a demand. Back pay is appropriate only where a party,

who would ordinarily be entitled to pay, has been deprived of

that right by the actions of another. In the instant case,

Appellant has not been deprived of any pay at all. Maternity

leave is a leave without pay. Even tenured teachers are not

entitled to pay for maternity leave and this holds no matter

how long the teachers are required to stay off either because

they are not ready to return or because no place has been

found for them. (A. 35a) By demanding back pay in this case,

8.

Appellant is seeking special treatment which no other teacher

receives.

If it were shown that Appellant had attempted to

return to work after the birth of her child and she was refused

because she was a probationary teacher, then a good argument

could be made that she was entitled to back pay. But that

simply is not the case here. The District Court has found, and

the record supports the fact that Appellant neither alleged nor

proved that she attempted to return to work and was refused by

Appellees. Therefore, it is mere speculation whether there

were positions open for which Appellant was qualified. Likewise

it is mere speculation whether Appellant would have been rein

stated since there is nothing to show that there were vacancies

for which Appellant was qualified.

The Appellees were not obligated to initiate an offer

of reinstatement to Appellant. This is not done with respect

to any other teacher on maternity leave whether the teacher be

tenured or probationary. The regulations governing maternity

leave put the burden on the maternity leave teacher to notify

the school system when she is ready to return to the system.

(A. 36a) It should also be noted that the District Court did

not order Appellees to offer Appellant reinstatement. The

District Court enjoined Appellees from refusing to re-employ

Appellant should she choose to resume teaching, on condition

9.

that there is at such time a vacancy within the school

system. (A. 157a)

The cases relied upon by Appellant as establishing

her right to back pay are simply not applicable to the facts

and circumstances of the instant case. Appellants' reliance

on United States V. Hayes International, 4 FEP Cases 411,418

(5th Cir. 1972) is misplaced as the District Court's order

denying back pay was not based upon the fact that it was not

requested in the pleadings. Indeed the Court's order

specifically states that Appellant's complaint prayed for back

pay. (A. 157a, 170a) The District Court simply refused to

speculate whether Appellant would have been rehired had she

applied since there was no allegation that she had applied

and been refused.

McFerren V. County School Board, 4 EPD 91-7652 (6th

Cir, 1972), was a case dealing with Negro school teachers who

were discharged because of their race. The appellate court

held that the District Court could properly award back pay for

the earnings the teachers lost without the need for a jury

trial on the question of damages where the back pay award is

made in connection with their equitable remedy of a reinstate

ment order.

McFerren can be distinguished on the basis of the facts.

McFerren, first of all, deals with Negro teachers who were

discharged. Appellant is a pregnant teacher who has not been

10.

discharged. Appellant did not lose any earnings as the

teachers did in McFerren. Teachers on maternity leave do

not receive pay so it is clear that, at least during the

period Appellant was with child, she was not, under any

circumstances, entitled to pay. After, the birth of her child,

it could not be said that Appellant was entitled to pay since,

as the District Court found, it would be mere speculation as

to whether there were positions open for which Appellant was

qualified. Moreover, unlike the McFerren case where the

District Court refused to rule on the question of back pay as

a part of the equitable remedy, the District Court in the

instant case made a specific ruling on back pay and denied it

on the equitable ground that it would involve too much

speculation. Finally, the McFerren case relies heavily on

Harkness v. Sweeny 'Independent School District, 427 F.2d 319

(5th Cir. 1970) where this court stated "An inextricable part

of restoration to prior status is the payment of back wages

properly owing to the plaintiffs, diminished by their earnings,

if any, in the interim." (Emphasis added) The key words in

this statement are "properly owing." As has already been

pointed out, there are no earnings properly owing to Appellant

in this case.

In Horton' v. Lawrence County Board of Education,

449 F .2d 793 (5th Cir. 1971), this court stated:

"Back pay is normally an integral part of the

equitable remedy of reinstatement used by

the federal courts to restore aggrieved

11 .

litigants to the position they should have

occupied had it not been for the unlawful

deprivation of their constitutional rights."

See Harkness v. Sweeny Independent School

District, 427 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970)

Neither this case, nor any of the other cases cited

by Appellant, stands for the proposition that in all civil

rights cases, the plaintiff is entitled to back pay. The

court states that back pay is normally an integral part of the

equitable remedy which must necessarily imply that the awarding

of back pay must depend on the facts of each case. And on the

facts of the instant case, back pay is simply not warranted.

Moreover, the court indicated in Horton, that the purpose for

back pay is to restore aggrieved litigants to the position they

should have occupied had it not been for the unlawful deprivation

of their constitutional rights. Under the facts of this case,

had it not been for Appellees' policy of denying maternity leave

status to probationary teachers, Appellant would have been

allowed maternity leave without pay. The order of the District

Court enjoining Appellees from refusing to hire Appellant

should she attempt to return to work had the effect of restoring

her to the position she should have occupied had it not been

for Appellees' rule. Appellant would not have been entitled to

12.

pay during maternity leave, and it has not been alleged that

Appellees refused to rehire her. Moreover, Appellant

returned to work on January 3, 1972, which was the earliest

date a position was open for which she was qualified.

The District Court in this case, sitting as a

court of equity, heard all of the evidence from both sides

and passed on all the allegations. Exercising its equity

jurisdiction, the court granted Appellant relief in the form

of an order permanently enjoining Appellees from denying

maternity leave to her and the. class she represented. The

Court found that Appellant had not alleged that she had

attempted to return to the school system and had been refused.

The record supports this finding, and the order of the district

court should be affirmed.

II.

Reasonable Attorney's Fees are' not a proper part

of the cost of this Action.

This action was brought under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983

and the District Court held it to be a denial of equal

protection of the laws for the Appellees to deny maternity

leave to Appellant and the class she represents. Section 1983

of Title 42 U.S.C. does not authorize the allowance of attorney's

fees. In fact, nothing at all appears in that section with

13.

respect to attorney's fees. Congress, in its wisdom, saw fit

not to include within Section 1983 any provision for the

allowance of attorney's fees and it is not within the province

of the courts to amend legislative enactments. In his

dissenting opinion in Mills V. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396

U.S. 375 (1970), the late Mr. Justice Black stated: "The

courts are interpreters, not creators, of legal rights to

recover and if there is a need for recovery of attorney's fees

to effectuate the policies of the act here involved, that

need should in my judgment be met by Congress, not by this

court."

None of the cases cited by Appellant construed

Section 1983 of Title 42 U.S.C., and none of these cases hold

that attorney's fees are allowable under Section 1983. In

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968),

a class action was brought under Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, Section 204 (a), 78 Stat. 244, 42 U.S.C. Section

2Q00a-3(a). Under the foregoing sections, Congress had enacted

provisions for attorney's fees and the Court held that the

successful litigants were entitled to attorney's fees to

encourage individuals injured by racial discrimination to seek

judicial relief under Title II. Unlike Sections 204 (a) and

2000a-3(a) of 42 U.S.C., where attorney's fees are expressly

allowed, there is no similar provision under Section 1983.

14.

It has long been held that a federal court may

award counsel fees to a successful plaintiff where a defense

has been maintained in bad faith, vexatiously, wantonly, or

for oppressive reasons. 6 Moore's Federal Practice 1352

(1966 ed.). However, there is no evidence that Appellees

acted in bad faith, vexatiously or wantonly in this case.

The action in Lee' v. Southern Home' Sites Corp. ,

444 F.2d 123 (5th Cir. 1971} was brought under 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982 and its holding is not applicable in the present

case since this case was brought under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983.

Similarly, the action in Clark, v. American' Marine Corporation,

320 F. Supp. 709 (E.D. La., 1970)., a'ff 'd per curiam, 437 F. 2d

959 (5th Cir. 1971), was brought under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, and the provisions of that act allows

attorney's fees. Finally, the rationale for awarding attorney's

fees in Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970)

does not enter into this case. In Mills, the Court stated that

attorney's fees were awarded to impose the expense upon the

class that benefited from the results and that would have had

to pay the expenses had it brought the suit. If the Mills

case is applicable at all, it is authority for the proposition

that the class appellant represented, i.e., probationary

teachers, benefited from the litigation and should be liable

for attorney's fees.

15.

The law in this circuit is that federal district

courts may, at their discretion, award attorney's fees in

civil rights litigation where the actions of the defendants

are unreasonable and obdurately obstinate. Horton v. Lawrence

County Board of Education, 449 F.2d 793 (5th Cir. 1971). It

was therefore, well within the discretion of the District Court

to deny Appellant attorney's fees especially since there was

no allegation that Appellees were unreasonable or obdurately

obstinate.

For the foregoing reasons, it is urged that the

order of District Court be Affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Lenwood A. Jackson

3405 First National Bank Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Warren C. Fortson

2400 First National Bank Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Attorneys for Defendants-

Appellees

16.

This is to certify that I served copies of the

Brief for Defendants-Appellees on Elizabeth R. Rindskopf,

Moore, Alexander & Rindskopf, 1154 Citizens Trust Bank

Building, 75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E., Atlanta, Georgia; Jack

Greenberg, William L„ Robinson, 10 C .'Lumbus Circle, New

York, New York; Harriet Rabb, 435 West 116th Street, New

York, New York, this ' ' ' day of March, 19 72, by depositing

same in the United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

Attorney’ for"Defendants-Appellees

17.