Wellington Hereford v. Huntington Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 14, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wellington Hereford v. Huntington Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1974. 4748e41d-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/792bbd2d-e5bd-445b-aea7-85a8fd5c1e6d/wellington-hereford-v-huntington-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

sgrjxqux^xa Jog: sAsuaoq.q.V

6T00I XZOA M9N 'qxoA A\aN

apa-xxo sn q u in xo o o i

NIHHOVHD T NVWHON

o a a a N a a a o > io v r

£ 0 2 S£ Bu req^xv 'u re q B u x u u x a

qqaojx s n u a A V q q q B x g X2T2

£ 0 2 S £ BureqBXY 'u r sq B u x u a x a

qqaojsl e n u sA V q q a n o j 0£9T

AaasoNiTTie Tiazao

[saaaaaaav] saauaiiYria aoa aaiaa

UOTSIAId

U J a q se sq q a o N ''e u req^xY JO q.Dx;rq.sxa uxaqqxojsi aq i,

x o a q x n o o qD T jrq sxa s a q a q s p a q xu fi aq i, u icua x ^ ^ Y

* saaxx9<5<5v-s quapuagaa

i .-[-•e

j3 'Noiiivonaa ao oavoa aaaiASiimH

'voiyawv ao saa,vis aaj.ian

'sg:g:xq.uxx>xa

/*x^ J3'ai 'crHoaaaaH noj.oniti3m aiNNOS

£9££-^Z. *ON

■imoaio Hiaia am aoa

NOiwaN *o snimawaa

SA

'qtrexX^dY

--iouaAaaqui-g:jxqux'ex<J

savaaav ao ianoo sa>ivis aa^im am ni

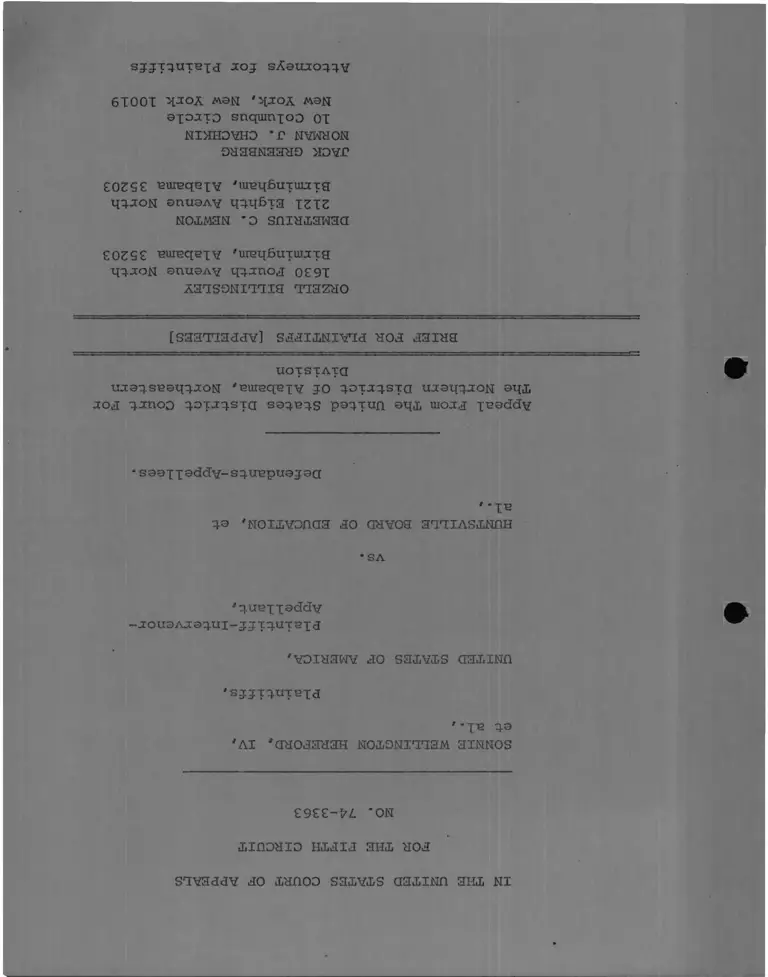

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TIIE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-3363

SONNIE WELLINGTON HEREFORD, IV,

et al. ,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-

Appellant,

vs.

HUNTSVILLE BOARD OF EDUCATION, et

al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for the plaintiffs

[appellees], certifies that the following listed parties have

an interest in the outcome of this case. These representations

are made in order that Judges of this Court may evaluate possible

disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local Rule 13 (a):

1. The original plaintiffs who commenced this action in

1963 are Sonnie Wellington Hereford IV, by his father and next

friend, Sonnie Wellington Hereford III; Herman Barley, by his

father and next friend Howard Barley; Rodney Monk, by his father

and next friend Luther Monk; John Anthony Brewton, by his mother

and next friend Sidney Ann Brewton; Veronica Terrell pearson, by

her mother and next friend Odelle Lacy Pearson; James Bearden, Jr.,

by his mother and next friend Georgia Bearden; and David C. Piggie,

by his father and next friend Rev. Cleveland A. Piggie.

2. The original plaintiffs above-named commenced and main

tained this action as a class action pursuant to F.R.C.P. 23 on

behalf of other Negro children and. their parents in Huntsville,

Alabama.

3. The United States of America intervened in this action

in 1966.

4. The defendants are the school Board of Huntsville,

Alabama and its members, and the Superintendent of Schools of

Huntsville, Alabama.

■- V / j

NORMAN J. CHA.CHKIN

2

TABLE OF CASES

Acree v. County Bd. of Educ., 336 F. Supp. 1275

(S.D. Ga. 1972) ....... .......................... 4n

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction, 432 F.2d

36 2 (5th Cir. 1970) ............................. 6

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 409

F. 2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1969) .... ................... 7

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School Dist.,

446 F . 2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1972) ................... 7

Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Educ., 457 F.2d

1091 (5th Cir. 1972) ............................ 3,4

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 317 F. Supp.

555 (E.D. Va. 1970) ............................. 4n

Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943

(4th Cir.), cert. denied, 406 U.S. 905 (1972) .... 9n

Page

Brown v. Board of Education of Bessemer, 464

F. 2d 382 (5 th Cir.), cert. denied, 409 U.S.

981 (1972) ......... ...................... ....... 9n

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413

U.S. 920, 922 (1973) ................ ............ 6u

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734

(E.D. Mich. 1970), aff'd 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971) ............... 8,9

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction, 465 F.2d

878 (5th Cir. 1972) ............................. 5

Flax v. Potts, 404 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 1002 (1972) ........... ................. 7

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F .2d 801

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969).... 5

Table of Cases (Continued)

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463

F . 2d 73 2 (6th Cir.)., cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1001 (1972) .................................... 7

Kelly v. Cuinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973) ........... . 8,9

Page

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746

(5th Cir. 1971) ................................. 7

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 446 F.2d

911 (5th Cir. 1971) ................... ......... 5

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 427 F.2d

874 (5th Cir. 1970) ................ ............ 8

Medley v. School Board of Danville, 482 F.2d 1061

(4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1172

(1974) 3

Miller v. School Board of Gadsden, 482 F.2d 1234

(5th Cir. 1973) 8

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 427 F.2d 1005

(6th Cir. 1970) 7n

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, 489

F. 2d 18, 19 (6th Cir. 1973) .................. . 9n

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis, Civ.

No. 3931 (W.D. Tenn., Jan. 12, 1972) ........... 4n

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educ., 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) .............. . 8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................. 1,3,4n

United States v. Board of Educ., Tulsa, 429 F.2d

1253 (10th Cir. 1970) 8

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 417 F.2d

852 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied. 396 U.S.

1032 (1970) 7n

Table of Cases (Continued)

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d

848 (5th Cir. 1972) ........................... 6

Weaver v. Board of Public Instruction, 467 F .2d

473 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S.

982 (1973) ............. ........ .............. 4,5,9

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction,

448 F. 2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971) ..... ............ 5

Page

w

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-3363

SONNIE WELLINGTON HEREFORD, IV,

et al.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-

Appellant,

vs.

HUNTSVILLE BOARD OF EDUCATION, et

al. ,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Northern District Of Alabama, Northeastern Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS [APPELLEES]

Introduction

This brief is submitted on behalf of the original plain

tiffs, Sonnie Wellington Hereford, IV, et al., and the class

of black children whom they represent in this litigation.

Plaintiffs were the appellants in the earlier post-Swann

review of this case, No. 71—2641. Because of a misunderstanding

among counsel, plaintiffs did not participate in the evidentiary

hearing on July 10-12, 1974 in this case, following which

the Order which is the subject of this appeal was entered.

For that reason, plaintiffs did not file a separate Notice of

Appeal from that decree. Plaintiffs' counsel have been furnished

with a copy of the Record by counsel for the United States, and

file this Brief in order that the Court may be cognizant of

their views.

Plaintiffs agree fully with and support the excellent

Brief for the United States, and we shall accordingly attempt

to be as succinct as possible and to avoid any duplication

of the thorough discussion and well-reasoned analysis in the

government's brief.

Statement of the Case

The government's Statement is accurate and basically

complete. Plaintiffs would emphasize that when the zoning plan

(Plan A) for Cavalry Hill and Terry Heights was approved by

fc.

the district court and this Court in 1971, there was little

focus upon some of the practical problems which have contributed

to the subsequent failure of the plan, such as the difficulty

of access to the school from the predominantly white portion of

1/

the enlarged zone (see Tr. 450-53), and the board's cancellation

1/ References are to the transcript of the July 10-12, 1974

proceedings.

2

of student transportation to the school (Tr. 236).

The 1971 appeal presented to this Court the abstract

question, without an extensive factual record of the sort now

before the Court, whether the projected enrollments at Cavalry

Hill and Terry Heights (under Plan A) were so substantially

disproportionate that, without allowing a period of actual

implementation within which to judge its resu3.ts, the case

should have been returned to the trial court with instructions

to adopt a new scheme. The relevant Swann language was novel

and uninterpreted; the plan as a whole projected significant

changes in the racial composition of many Huntsville schools.

Under these circumstances, this Court in a short per curiam

opinion said that it found no error in the district court's judg

ment that Plan A should be given an opportunity to work.

The present appeal involves new facts and legal issues,

neither debated nor resolved in the 1971 proceedings. Whatever

the Court's view of the "substantial disproportion[ality]" of

two 65% black schools in a system of Huntsville's size which is

but 17% black, cf. Medley v. School Board of Danville, 482 F.2d

1061 (4th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 414 U.S. 1172 (1974), we

submit that the insufficiency of a plan which, in that system,

projects the continued operation of two contiguous schools

respectively 72% and 97% black, is now apparent. See Boykins v.

3

Fairfield Board of Education, 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir. 1972);

Weaver v. Board of Public Instruction, 4G7 F.2d 473 (5th Cir.

1972), cert. denied, 410 U.S. 982 (1973). Additionally, while

the district court was reluctant in 1971 to require implemen

tation of Plan B in part because it would require the institu

tion of new grade structure patterns in the Huntsville system,

this year the board itself has proposed a multi-year transition

to a new system-wide pattern, presenting an appropriate opportunity

to make changes which further desegregation.

ARGUMENT

The District Court Should Require Prompt

Desegregation Of Cavalry Hill and Terry

Heights niementary Schools by The Most

Efficacious Means Available

This case is governed by principles now settled in this

and other Circuits. Like Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Educ.,

supra, it is a case in which a desegregation plan, which had

<0

received prior judicial approval based upon its "paper" pro

jections, turned out in practice to be far less effective than

2/

had been anticipated by its designers. Under these circum-

2/ It is in fact likely that Plan A was fashioned by HEW prior

to the decision in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)[see Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants in No. 71-

2641, at pp. 2-3] and under artificial constraints with respect

to technique, see Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F. Supp.

555, 563-66 (E.D. Va. 1970); Acree v. County Bd. of Educ., 336 F.

Supp. 1275 (S.D. Ga. 1972); Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis,

Civ. No. 3931 (W.D. Tenn., Jan. 12, 1972). Whatever its defects in

design, however, it is now clear that the plan did not work.

4

stances, and particularly within the three-year period during

which district courts retain jurisdiction for the purpose of

insuring that fully unitary school systems are actually

established, e .3 ., Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction,

448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971), new initiatives to eliminate

schools which remain substantially disproportionate in racial

composition are required by the Constitution in order to extirpate

the last vestiges of the dual system. As this Court has noted

in other contexts, good faith implementation of a plan adequate

as conceived, but ineffective in practice, cannot substitute

for constitutional compliance, Hall, v. St. Helena Parish School

Board, 417 F .2d 801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904

(1969); unitary status is not achieved by a plan which does not

prove itself over time. Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board,

446 F.2d 911 (5th Cir. 1971); and plans which once received the

judicial imprimatur may fail to withstand subsequent scrutiny

in the light of more recent decisions, Ellis v. Board of Public

Instruction, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972).

The fact that desegregation issues in Huntsville have

narrowed to the continued existence of two disproportionately

black elementary schools does not make the constitutional

problem de minimis. Cf. Weaver v. Board of Public Instruction,

supra. Cavalry Hill was a state-imposed black school under the

dual system, and it has remained a black school throughout the

years of litigation and the variety of plans in this case.

5

Without question, the three-year attempt to desegregate by

rezoning a minority of white students (in this heavily white

system) into the school, has failed. Hornbook law in this

3/

Circuit requires that alternatives other than zoning be

utilized. Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 427 F.2d

874 (5th Cir. 1970); Allen v. Board of Public Instruction, 432

F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970); see United States v. Texas Educ. Agency,

467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972); Cisneros v. Corpus Christi

Independent School District, 467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, 413 U.S. 920, 922 (1973).

Implementation of an effective plan cannot await the

predicted three-year success of locating a 4th and 5th grade

career education program at Cavalry Hill, Miller v. School Board

4/

of Gadsden, 482 F.2d 1234 (5th Cir. 1973). Nor can desegregation

3/ The existence of a deep and wide ditch as a physical barrier

between the predominantly black and predominantly white residen

tial sections of the 1971 Cavalry I-Iill zone (see Tr. 450-53)

indicates not only part of the reason for the failure of the 1971

plan, but also a weakness in any rezoning plan involving Cavalry

Hill. It is precisely where factors such as this, and location

of the school in the middle of a virtually all-black residential

comples (Tr. ), are found, that this Court has traditionally

required the use of pairing and non-contiguous pupil assignment

methods.

4/ The testimony showed that the school system had conducted no

surveys of general white student interest in the "exemplary"

program to be established at Cavalry Hill (Tr. 97). The Super

intendent thought white students wou3.d not attend the school even

if rezoned into it as a 70% majority (Tr. 99-100) but he maintained

that the career education program would nevertheless be drawing

more whites to Cavalry Hill within three years (Tr. 133.) . The

principal of the school, however, did not anticipate any increased

enrollment of whites as a result of the program (Tr. 538-39).

6

of Cavalry Hill be ignored because of projections of white

5/

flight. Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education, 409

F.2d 1287 (5t:h Cir. 1969). Cfh Bell v. West Point Municipal

Separate School District, 446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1972); Lee

v . Macon County Board of Education, 448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971).

It is also well established that formerly white schools

which shift in racial composition, for whatever reason, before

§/

the desegregation process has been completed, may not be

exempted from conversion to unitary, nonracial status as required

by the Constitution. Flax v. Potts, 404 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1002 (1972); Kelley v. Metropolitan

County________Board of Education, 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972). This principle clearly

applies to a school which is now as substantially disproportionate

5/ This is true in spite of the system's claim that its fears

of white non-attendance are based upon actual experience, cf.

United States v. Hinds County School Board, 417 F.2d 852 (5th

Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1032 (1970); Monroe v. Board

of Commissioners, 427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir. 1970); in any event,

it seems doubtful that the Cavalry Hill experience furnishes an

appropriate base from which to project the results of a plan which

would seek to assign pupils to the school in such a way as to make

its racial composition more typical of the entire system (see Tr.

410) .

6/ Even if the construction of a project by the local housing

authority, with the support of the United States Department of

H.U.D., were shown to be a primary factor in altering the racial

composition of the attendance zone established prior to 1970 for

the Terry Heights school, that would hardly insulate the Board of

Education from responsibility for its determination to maintain

7

in racial composition as is Terry Heights; it was implicitly

recognized by the board and by the trial court in altering

the board's proposal to reassign middle school students from

Cavalry Hill to Stone, which would have significantly increased

the concentration of minority students at the latter. Indeed,

the board's willingness to undertake widespread alteration of

grade structiire, or repeated attendance zone changes (e.c£.,

Tr. 280-81) while carefully eschewing changes which would reduce

the degree of segregation throughout the system, resembles the

sort of conduct which has been held to violate the Fourteenth

Amendment in cases arising outside this Circuit. E.cp , Kelly v.

Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 9.19

(1973); Spangler v. Pasadena City Bcu of Ecluc ■ , 311 F. Supp.

501 (C.D. Cal. 1970); Davis v. School Dist, of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970), aff‘d 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971); United States v. Board of

Education, Tulsa, 429 F.2d 1^53 (10th Cir. 1970). As the Courtw

6/ (Continued)

that zone, unaltered, despite increasing racial concentration,

while regularly reshaping nearby attendance zones for other

purposes. As the district court in the Pontiac case aptly put

it,

The question is no longer where the first move

must be made in order to accomplish equality

within our society; the question has become,

and possibly has always been, who has the power

and. duty to make those moves so as to advance

the accomplishment of that equality. [309 F.

Supp., at 742]

8

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit has held, inconsistent

application of educational criteria which produces significant

racial segregation is a powerful indicator of intentional

discrimination by the official agency. Davis v. School Dist.

of Pontiac, supra; see also, Kelly v. Guinn, supra.

Fortunately, this case presents no great practical

difficulties. There are numerous alternatives for desegregating

Cavalry Hill and Terry Heights — many considered and rejected

1/

by a school board intent upon rejecting "busing for desegregation"

(see Brief for the United States, at 18-20) and others which were

developed at trial (Tr. 287-89, 292-94) which are practical,

indeed classically simple in design and execution. Cf. Weaver

v. Board of Public Instruction, supra. The case should, therefore,

7/ The system's avowed aversion to the use of "busing" to assist

in the desegregation of Cavalry Hill and Terry Heights is almost

ludicrous in view of the extensive pupil transportation, including ,

routes many times the length of those projected under the

alternative plans (Tr. 500-02, 508, 518), presently operative in the

Huntsville system. Certainly the district court could ensure

adequate transportation provision by the city council and city

transit company should the school board encounter any difficulty

in arranging suitable bus service to carry out an effective

desegregation plan. See, <2.g. Northcross v. Board of Education,

489 F.2d 18, 19 (6th Cir. 1973); cf. Brewer v. School Board of

Norfolk, 456 F .2d 943 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 905

(1972); Brown v. Board of Education of Bessemer, 464 F.2d 382

(5th Cir.), cert. denied, 409 U.S. 981 (1972).

9

- ox -

sq q x q u x sp a ^oq sA ou uoqqv

6T00I a MSN 'quoA M3N

opo^TO snqiunxoo oi

NIHHDVHD T NVWHON

D H aaN aaH9 >td v j?

£0ZS£ s u i s q s i v 'u is q B u x u u x a .

qq^O N sn u o A V q q q B x a TZTZ

nto.t mo’nt * p\ SHITHZHH3G

£02S£ Bursqsxv 'ureqfiuxuiixg

qquoN snu3AV qqunog 0£9T

Aaa'SDNiaaia tih^ho^ nrT.-

'paqqxuiqri.s Axxnjqoedsa'a

*spooqos

Ausquouispa sqqBxan /xt-xarr, p a s xiTH AxpsABO jo suoxqxsoduioo [exosx

o q su o xq jro d o ad sxp oqq soqsuxuixxs qoxqM sxxxA squ n H qo sp o o q o s

A xsq u su io xs xoq uspd u o x q sB sJcB sse p m©u b 'a q x p opqxssod qssxp^so

aqq. qs ‘ qu01110pduix p u s OAOxdds 'o s x A a p 04 iopxo ax p e i in b a a

e q Abui s s sB u xp o e o o xd q o n s oqox.duioo p u s sfiuxxseq qous ppoq oq

suoxqonuq-sux q x o x x d x o qqxM qxnoo q oxx:qsxp eqq oq pspu su isx oq

IT

Z0Z9£ 'Euieq'eTY 'u re q b u x u n x g

e s n o q q a n o o x0:i:0P 3 d £9Z

AaujoqqY saqBqs paqxun

•xajrzraiJS ugutAb m - u o h

0£90Z *0 *a ‘'uoqbuxqsBM

aoxqsnr jo quauq.;tGdaa

uoxsTAia sqqbxg XTAT0

•bsg ' s s o j d •q qaBW

T08££ aumqBXY 'aXTTAS3-unH

LZ9 x o g *o *<3

•bsg 'suA-eg *q aor

:sa\oxtox sg passaa'ppB

'pxBdaad abBqsod ' s s b x o qs^xj 'XT'0111 s a q a q s paqxun 0 tH- UT 0ur®s

buxqxsodap Aq 'oqaaaq saxqjrad aqq J05 x0SunoD uodn [saaxx0ddv]

sjjxqxiXBXd ^oj qaxjrg buxobaaog: aqq jo saxdoo (g) OMq paA.xas 1

' I7Z.6T ' J a q o q o o 5 0 Aap qqx-x sxqq uo q0 qq Ajxqzrao Aqaaaq I

aoiAgas ao ajjvoidiiLHaD