Milliken v. Bradley Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1974. b40213b8-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/794678bb-3682-4381-bdd6-33025a7e95b9/milliken-v-bradley-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

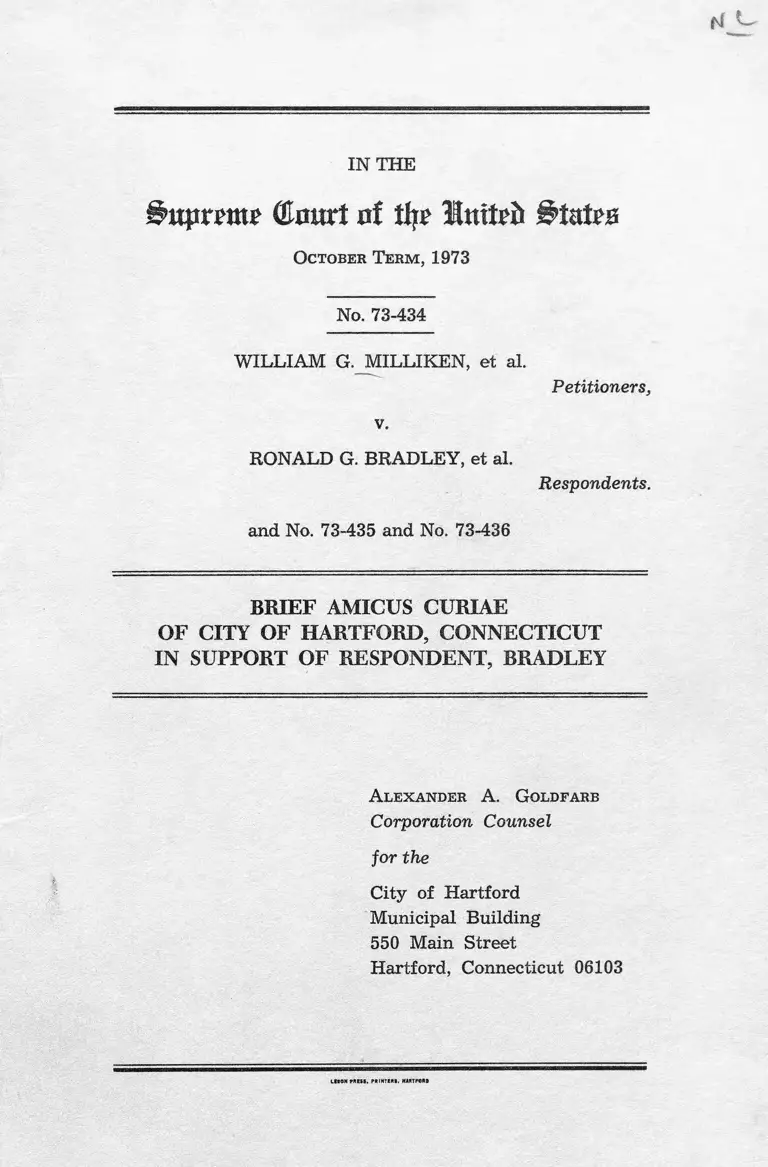

IN THE

&upmttp (&mvt of tty Inttpft BUUb

October Term , 1973

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.

Petitioners,

v.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.

Respondents.

and No. 73-435 and No. 73-436

BRIEF AM ICUS CURIAE

OF CITY OF H ARTFORD, CO N N EC TIC U T

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT, BRADLEY

A lexander A. Goldfarb

Corporation Counsel

for the

City of Hartford

Municipal Building

550 Main Street

Hartford, Connecticut 06103

LESON PRESS. PRINTERS. MRTPORS

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page

AMICUS CURIAE AUTHORITY..............................................1

INTEREST OF THE CITY OF HARTFORD............................1

QUESTION PRESENTED...................................................... 3

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTORY BACKGROUND ................. 3

A. The Structure of Changes in Detroit and

Hartford fit into a Pattern of Development

in the Nation’s Metropolitan Areas. ......... 3

II. STATE SCHOOL AUTHORITIES, FOR THE

STATE OF MICHIGAN AND ELSEWHERE IN

THE COUNTRY, THROUGH AFFIRMATIVE

ACTS, HAVE FOSTERED, NURTURED, AND

PROMOTED THE USE OF SCHOOL DIS

TRICT BOUNDARY LINES TO ACCOM

PLISH THE SEGREGATION OF PUBLIC

SCHOOL CHILDREN ON THE BASIS OF

RACE AND ARE, THEREFORE, IN CLEAR

VIOLATION OF E Q U A L PROTECTION

GUARANTEES AS ESTABLISHED UNDER

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT OF THE

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES. 5

A. Policies and Instruments of Segregation

Existed Prior to Brown 1............................. 5

B. This Court’s Holdings in Brown I and II

Altered The Pattern of State Segregatory

Practices in Public Schools........................ 6

C. Affirmative Acts of Public Authorities

Provided A Segregation Environment for

Both School and Residential Location

Decisions......................................................... 8

D. State School Officials, in Michigan and

Elsewhere in the Nation, Through Affirm

ative Actions, Not Only Adapted to The

Effects of Demographic Change, But More

Significantly, Determined and Structured

The Course of Metropolitan Development. 10

III. THE SCOPE OF THE CONSTITUTIONALLY

ADEQUATE REMEDY TO SEGREGATED

SCHOOLS IN URBAN AREAS IS NOW

METROPOLITAN. A REMEDY PRESCRIBED

ONLY FOR CENTRAL CITY SCHOOL DIS

TRICTS WOULD CREATE “SEPARATE BUT

ii

EQUAL” SCHOOL SYSTEMS........................... 13

A. The Relevant School Community In The

Nation’s Metropolitan Areas In 1954 Was

the Municipal School District.................... 14

B. The Relevant School Community For

Purposes of Desegregation Is Now Metro

politan, Not Municipal. .............................. 16

C. Re-segregation Within the Central City

School Districts Is a Symptom of Regional

de jure Segregation....................................... 18

D. The Nature of the Constitutional Violation

in the Instant Case Compels the Affir

mation and Adoption of a Metropolitan

Remedy. ....................................................... 20

IV. THERE IS AN INHERENT AND ESSENTIAL

UNITY BETWEEN THE INTEREST OF

CENTRAL CITIES AND THEIR SUBURBAN

iii

TOWNS FORGED BY DOMINANT LONG

TERM FORCES WITHIN THE ECONOMY..... 22

A. Developments in Technology and the

Economy Accelerated Suburban Resi

dential Growth............................................. 24

B. The Increasingly Complex Socio-Economic

Interlock Between City and Suburbs al

tered the Balance Between the Interests

of Individual Communities and Those of

the Larger Metropolitan Region as a

Whole.............................................................. 25

C. Metropolitan Community of Interest Was

Legitimized and Made Formal by Private

Citizens and All Levels of Government. .. 26

D. The Growth of Metropolitan Areas Has

Been Subverted by Divisive Forces.......... 29

CONCLUSION ....................................................................... 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO APPENDIX.......................... la

APPENDIX 2a

IV

TABLE OF CITATIONS

CASES Page

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483;

74 S. Ct. 686; 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954) ............................ 4

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 301;

75 S. Ct. 753; 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955) .......................... 4

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430; 88 S. Ct. 1689; 20 L. Ed. 2d 716 (1968) ............. 7

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1; 91 S. Ct. 1267; 28 L. Ed. 2d 554 (1971) 8

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189; 93 S. Ct. 2686; 37 L. Ed. 548 (1973) ........... 8

FEDERAL STATUTES

20 USCA 1602 ....................................................................... 28

20 USC A 1608 ....................................................................... 28

AMICUS CURIAE AUTHORITY

The City of Hartford, a political subdivision of the State

of Connecticut, is filing this Brief Amicus Curiae sponsored

by its chief law officer, the Corporation Counsel, as duly

authorized by formal vote of the Court of Common Council

of the City of Hartford, pursuant to Rule 42 (4) of the Rules

of the Supreme Court of the United States.

INTEREST OF THE CITY OF HARTFORD

The City of Hartford, a political subdivision of the State

of Connecticut with a population of 155,000, has a vital, direct

and immediate interest in this case, more particularly as to

the nature and extent of the desegregation remedy this

Court may prescribe. The decision here will have an enduring

and critical effect upon metropolitan areas in this country

and will shape and structure the future relationships be

tween city and suburb, between black and white, between

poverty and wealth.

The District and Appellate Courts have held that the co

terminous boundaries of the city and the school district of

Detroit do not have a racially neutral effect upon school sys

tems in the Detroit metropolitan area; rather, that the exist

ence of said boundaries, coupled with certain affirmative acts

of State school authorities, has caused and continues to cause

and promote racial segregation between schools located in

Detroit and those located in its surrounding suburbs. The

Petitioners argue not only that school district lines in the

Detroit metropolitan area delineate geographically separate

entities, but also, that said districts are legally, socially and

politically unrelated and independent units. Following this

rationale, the Petitioners suggest that the proposal that sub

urban school districts be included in the desegregation plan

was erroneous and contrary to law, and further that a

2

“Detroit only” plan of desegregation is the constitutionally

adequate and the only permissible remedy.

The 27,000 public school students of the City of Hart

ford are confronted with conditions similar to those in

Detroit in that, within the context of school district lines

having been geographically established on a town-by-town

basis, segregation exists to such an extent as to create racially

identifiable schools within the city and between the city and

its surrounding suburbs. In Detroit, however, no systematic

congruence between town and school district is found.

In a suit presently pending in the United States District

Court for the District of Connecticut, instituted by the Mayor

and the members of the Court of Common Council, the City

of Hartford alleges, on behalf of its citizens, that the Connect

icut State Department of Education has created and main

tained racially-identifiable schools and that through its offi

cial policies and administrative actions, has licensed and

sanctioned the containment of minority student concentra

tions in the city proper.

Further, it is alleged that said acts have contributed to

and promoted the white identity of suburban schools, thereby

creating a dual school system which violates the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. (City of Hartford et al. v. Thomas Mes-

kill, et al., Civil Action No. 15074, D. Conn. May 30, 1972.)

The Board of Education of the City of Hartford and the

Connecticut State Department of Education are also parties

Defendant in a school desegregation suit instituted in 1970.

(Kenyetta Lumpkin, et al. v. Thomas Meskill, et al, Civil

Action No. 13,716, D. Conn. Feb. 20, 1970.)

The desegregation remedy determined by this Court will

tangibly and gravely affect the scope of any remedy to be ap

3

plied in either or both of the pending Hartford cases. The dual

school system existent in the Hartford region is similar to

that in the Detroit region. In both metropolitan areas the sys

tems are constitutionally obstructive and should be dis

mantled, or made permeable on a metropolitan area basis

commensurate with the scope and extent of the harm inflicted

upon their respective public school students.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is a metropolitan remedy to de jure segregation as found

in Detroit constitutionally adequate, appropriate and feasible

under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and under the decisions of this Court?

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTORY BACKGROUND

A. The Structure of Changes in Detroit and Hart

ford fit into a Pattern of Development in the Nation’s

Metropolitan Areas.

The involvement of both the Hartford School District and

the Detroit School District in Federal District Court desegre

gation suits is not an adventitious circumstance. To the con

trary, correlative to developments in their respective public

school systems over the past two decades, patterns of economic

and social interdependence have acted to create conditions

within each city which are, today, essentially similar.

In the early 1950’s, the public school population of both

cities was predominantly white-dominated. Each of these

cities was fiscally sound and had no difficulty providing

needed public services for all its citizens; and each continued

to attract new business investment within its municipal

boundaries.

4

By 1970, these conditions had been dramatically re

versed. Detroit and Hartford, like scores of other United

States cities, fit into a national pattern of metropolitan devel

opment which has left the central cities in a state of crisis and

decay. Over the past twenty years, a methodical, pervasive

and continuous depletion of affluent white households from

the central cities, resulting in part from racial segregation in

the schools accompanied by the in-migration of blacks

and low-income households, upset the population balances

needed to maintain the stability and vitality of these urban

communities. This exodus to the suburbs of the economically-

advantaged households and of the business community which

serves them precipitated an erosion of the tax base which,

concurrent with the increased costs of providing needed pub

lic services, contributed greatly to the phenomenon which is

now known as the “ Urban Crisis” .1 The forces which shaped

the emerging structure of legal, political and socio-economic

relations are complex and protean and need not be chronicled

here. There is, however, one salient factor which, because of

its importance, merits attention of this Court in its delibera

tions of the instant case.

A major contributory cause of the spiral of urban decay

which has characterized the central cities of this nation in

the intervening years since 1954, has been the concerted,

evasive and illegal policies and administrative actions of state

school authorities to circumvent, subvert, and neutralize this

Court’s mandate as established in the historic decisions, Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483; 74 S. Ct. 686;

98 L. Ed. 873 (1954); Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U.S. 301; 75 S. Ct. 753; 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955).

5

II. STATE SCHOOL AUTHORITIES, FOR TH E

STATE OF M IC H IG A N AN D ELSEW H ER E IN TH E

COUNTRY, TH R O U G H AFFIRM ATIVE ACTS, H AVE

FOSTERED, NURTU RED , AN D PROM OTED TH E

USE OF SCHOOL DISTRICT BOUNDARY LINES TO

ACCOM PLISH TH E SEGREGATION OF PUBLIC

SCHOOL C H ILD R EN ON TH E BASIS OF RACE A N D

ARE, TH EREFORE, IN CLEAR VIO LATIO N OF

E Q U A L PROTECTION GUARANTEES AS ESTAB

LISH ED U N D ER TH E FO U R TEEN TH A M E N D M E N T

OF TH E CONSTITUTION OF TH E U N ITED STATES.

A. Policies and Instruments of Segregation

Existed Prior to Brown I

In the historical period previous to 1954, the policy of

segregating and isolating public school children on the basis

of race was usually accomplished within school districts. In

some instances, all black districts were operated as separate

administrative units. The instruments for achieving racial

segregation in public schools differed by region of the country.

Southern states were direct and perhaps more forthright in

their discrimination, while Northern states effected racial

segregation of school children by more subtle and hypocritical

means.

In the Southern regions of the country, state systems of

public education, as administered through local school boards,

operated within a context of state laws which explicitly

provided for the separation of races within the confines of

each school district. In the North, absent such state laws,

racial segregation within school district boundaries was

achieved by a variety of administrative decrees, by school

6

construction, and by drawing school attendance zones in

conformance with segregated housing patterns.

Since in a growing, mobile society, the housing patterns of

these racially-identifiable communities did not remain demo-

graphically stable, an increase in the numbers of children re

siding within existing school attendance zones and shifts in

the geographic distribution of minority housing were accom

modated through two mechanisms which had the effect of

affirming or re-establishing racial segregation within school

districts. Such increase in the numbers of public school chil

dren within school attendance zones were absorbed through

a policy of allocating funds for the construction and place

ment of new school facilities on the basis of race. In response

to shifts in housing patterns which threatened to alter the

racial identity of school attendance zones, local school author

ities adopted a pattern of optional attendance zones, transfer

policies, and the gerrymandering of zones to achieve max

imum racial segregation.

In summary, the pattern of public school segregation

which emerged from the pre-1954 period was one of racially

separate school attendance zones in the North and racially

separate schools in the South. Each system effectively created

racially identifiable schools, thereby yielding a similar result.

B. This Court’s Holdings in Brown I and II Altered

The Pattern of State Segregatory Practices in Public

Schools.

In the years immediately following Brown I, the imple

mentation of this Court’s order through the creation of uni

tary, non-discriminatory school systems within certain muni

7

cipal school districts, did not take place to any substantial de

gree. What token or piecemeal changes did take place were

not sufficient to counteract the effects of increasing numbers

of minority children in the center city and an intensified

racial exclusion of blacks from most suburban areas.

School district lines ceased to function merely for the

purposes of state administrative convenience, but rather as

sumed a new meaning which, with the passage of time, would

come to have broad socio-economic and legal implications.

Already under pressure from demographic changes and,

having been denied the freedom from judicial scrutiny or

constraint which it had historically enjoyed, intra-district

segregation evolved with the growing black population to seg

regation between central city school districts and those of the

suburbs.

While school district boundary lines had historically sep

arated suburban school children from their urban counter

parts prior to 1954, they did not have the effect, nor were

they generally used as a device, to contain and separate mi

nority children from their white school counterparts. With

the increasing threat of the actualization of desegregation

of central city schools, and as administrative devices within

cities failed to keep certain schools white, these legal, poli

tical, and geographic boundaries began to intrude upon

and contribute more substantially to the residential location

decisions of mobile, white families.

Within the period since Brown I and II, through its

subsequent decisions, this Court has elaborated, extended and

defined its intent and the methods to be used to eliminate all

vestiges of state-imposed segregation from the public schools.

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430; 88 S. Ct. 1689; 20 L. Ed. 2d 716 (1968);

8

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1; 91 S. Ct. 1267; 28 L. Ed, 2d 554 (1971).

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189, 93 S. Ct. 2686; 37 L. Ed. 2d 548, (1973);

It should be borne in mind that, with the erosion of the power

of school attendance zones within school districts to sepa

rate geographically white from minority students, white

families with sufficient income could seek sanctuary

from changing school enrollments by establishing residence in

white suburbs from which blacks were generally excluded.

Just as the scope and extent of school segregation had been de

termined in the Northern states by fixed school attendance

zones within school districts in the pre-1954 period, in the

years following Brown I, the scope and extent of segregation

between school districts throughout the nation was predicated

upon the boundary lines between school districts.

A critical element which, both before and after 1954, con

tributed to and shaped the residential location decisions of

relatively affluent white households was their expectation

that the effects of public racial segregation and private preju

dice and low income would effectively restrict and contain the

residence of black families to the ghetto areas of the central

cities.2

C. Affirmative Acts of Public Authorities Provided

A Segregation Environment for Both School and Residen

tial Location Decision.

The decisions of literally millions of white households

to reside in the suburbs contributed to and shaped the pat

terns of segregation which presently exist between city and

suburban school districts3. The actions of individuals, however,

in their private capacities are not at issue in the instant case.

An important distinction exists beween the right of an indi

vidual to choose his or her place of residence, which is

afforded the protection of the United States Constitution, and

9

actions taken by public officials which have the known and

foreseeable consequence of denying another class of indi

viduals their constitutional rights. Whereas a wide latitude

of permissible behavior is afforded and sanctioned for indi

viduals, the Constitution requires that government officials,

in representing the interests of all people, conform with and

adhere to the highest principles and standards of human con

duct. This precept has been explicitly recognized with res-

spect to the obligations and responsibilities of school officials

in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294;

75 S. Ct. 753; 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955). II.

During the intervening period from 1954 to the present,

state boards of education in Michigan, Connecticut and else

where in the nation acted under a policy of complicity and

neglect.4 Having failed, post Brown, to eliminate school segre

gation in central cities at a time when it was possible to do so,

the official acts of state school authorities had the foreseeable

effect of reinforcing and aggravating existing school and hous

ing segregation. This led directly to a metropolitan community

best described as an expanding core of black schools sur

rounded by a ring of white public schools. Cognizant of the

increasing percentage of minority students within the center

cities, and with full knowledge that classroom construction in

suburban schools was planned for white students, state school

authorities affirmed and permitted school district lines to

function between city and suburbs in the same manner that

school attendance zones had functioned prior to 1954. This

policy of state boards and their local agents cannot, however,

be characterized as one of benign neglect.

State school officials have not merely acted to sanction

and passively condone inter-district segregation; rather, state

boards have fostered, promoted, and actively participated in

the establishment of racially dual systems of public schools

within the metropolitan areas of this nation.

10

The states, therefore, because of their failure to act, are

now faced with the fact that what must be done today will

require student assignment across district boundaries.

D. State School Officials, in Michigan and Elsewhere

in the Nation, Through Affirmative Actions, Not Only

Adapted To The Effects of Demographic Change, But

More Significantly, Determined and Structured The Course

of Metropolitan Development

Since 1950, dramatic demographic changes had to be

planned for, and accommodated by school authorities.

1. Population increased in the nation’s metropolitan

areas by 44.8 million from 1950 to 1970 (47.4%). (See Table

D, Appendix).

2. The population in central cities increased by 10 mil

lion from 1950 to 1970; the major increase taking place in the

earlier decade. (See Table D, Appendix).

3. Suburban population increased over the period 1950

to 1970 by 85.4%; an absolute increase of 34.8 million (from

40.8 to 75.6 million) (See Table D, Appendix).

4. In 1950, 34.6% of the total white population lived

in central cities, but by 1970 the figure had decreased to

27.8%. Net decrease of 2 million. The comparable figures for

the black population registered an increase from 44.1% in

1950 to 58.2% in 1970. (See Table D, Appendix).

5. In 1970, 59.4% of the white population in the metro

politan areas was suburban, while 78% of the black metro

politan residents lived in central cities. (See Table D, Ap

pendix).

6. For the white population in central cities, children

under 13 years old and adults between the ages of 25 and 44

11

years were the major age groups which lost population be

tween 1960 and 1970.5

Selective subsidies to urban and suburban school districts

for the transport of children to and from public schools, varied

planning assistance programs, the discretionary administra

tion of federal education grants, and a variety of other activi

ties constitute affirmative actions by state school authorities

which have shaped and fashioned their respective systems of

education. Paramount among such actions has been state par

ticipation in and responsibility for the construction of new

school facilities to adapt to, accommodate and plan for

changes in the patterns of residence which have character

ized our growing, mobile society.

As this Court has noted, decisions of school officials in

determining the geographic location of new schools will, in

conjunction with school assignment techniques, not only

“determine the racial composition of the student body in

each school in the system” , but will also act to determine and

structure the course of metropolitan development.

“People gravitate toward school facilities, just as schools

are located in response to the needs of people. The loca

tion of schools may thus influence the patterns of resi

dential development of a metropolitan area and have

important impact on composition of inner-city neghbor-

hoods.”

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S., ot 20-21; Keyes v. School District No.

1, 413 U.S., at 202.

The Petitioners would have this Court believe that school

districts are separate, unrelated and dissociated from one

another. Far from being unrelated to one another, school

districts in the suburban towns and that of the central city are

12

welded together in a relationship predicated on the racial and

economic prejudice of the affluent white families who leave

one center city so that their children might attend majority

white schools in the suburbs. The operation and presence of

a minority urban school district, by its very existence, implies

and affirms the existence of its white suburban counterparts

and is thus intrinsic to the patterns of intrametropolitan

migration. As legal and political subdivisions of a greater

whole, each element in this relationship necessarily functions

to separate school children by race. Just as urban implies sub

urban, so their relationship implies a prejudicial result.

Separate school districts, in close geographic proximity

to one another, having been created and maintained through

state action, are elements in and produce the conditions for a

process of state-supported racial segregation which, if allowed

to run its full course, will result in a geographically dual

society, divided by race, in this nation’s metropolitan areas.

This is Darwinism of another sort, wherein income

levels and racial prejudice intertwine to produce the perverse

result which now confronts public officials and private citizens

in Detroit, Hartford and other central cities in the Nation.

The selection process and the socio-cultural advance of one

class of citizens at the expense of another is predicated and

founded, not on biological supremacy, but rather on a malig

nant racism and the income differences which discrimination

has produced. What is all the more reprehensible and ab

horrent is that this selection process is ratified and legitimized

by the policies and administrative actions of state officials.

The result of this process is a metropolitan structure which

divides one sector of society against another and, as such, is

an aberrant form, a mutation, which stands contrary to the

Fourteenth Amendment and to the highest and best interests

of this nation and its citizens.

13

III. THE SCOPE OF THE CONSTITUTION

ALLY ADEQUATE REMEDY TO SEGREGATED

SCHOOLS IS NOW METROPOLITAN. A REMEDY

PRESCRIBED ONLY FOR CENTRAL CITY SCHOOL

DISTRICTS WOULD CREATE “SEPARATE BUT

EQUAL” SCHOOL SYSTEMS.

Two decades ago this Court noted the importance of

education as a function of state and local governments and

ruled that there was no place therein for the doctrine of

“separate but equal.” Brown I at 495.

In a recent decision, this Court reiterated that:

“ The constant theme and thrust of every holding from

Brown I to date is that state enforced separation of races

in public schools is discrimination that violates the Equal

Protection Clause. The remedy commanded was to dis

mantle dual school systems.”

Swann, 402 U.S., at 22.

In the difficult problem of practically dismantling dual

school systems, the Federal Courts are faced with two prob

lems. The first is to identify the community of school children,

minority and white, who have been harmed by state segre

gative practices; thereby, the Courts define the nature of the

constitutional violation. That is, the Courts must first discern

the geographic and social extent of the pattern of state segre

gation before it can frame an appropriate remedy.

The existence of state-created, racially identifiable schools

implies the segregation of minority students from the domi

nant society which is white. Segregation is a relation, and as

such, the very presence of a separated minority implies and

affirms its opposite — the presence of a majority. In deter

mining the nature of the constitutional violation, it is not

14

enough for the Courts to distinguish those schools which are

racially identifiable on a minority basis, but rather it is

incumbent upon the Courts to determine the extent to which

minorities have been actively separated, through state action,

from their white counterparts within and between school

districts.

Having so defined the community of school children

harmed, the second problem facing the Courts is the framing

of a remedy which would meet the criteria of being both con-

stitutionally-adequate, as well as being “practically flexible”

in its application. This Court has made explicit note, however,

that in the framing of a remedy the overriding consideration

is the constitutional adequacy of any plan of desegregation.

In 1955, when it rendered its decision in Brown II, the

Court recognized that differing fact situations might require

a variety of remedies depending on the relevant school com

munity. This Court expressly noted that to eliminate state-

imposed segregation it might be necessary to change school

district boundaries. In most metropolitan areas, however,

segregation could have been sharply reduced if prompt action

had been taken by limiting it to the central cities. What could

have been done was not done. That is why we are here today.

A. The Relevant School Community In The Nation’s

Metropolitan Areas In 1954 Was the Municipal School

District,

The racial geography of schools in the Topeka region at

the time of the Brown decision was congruent with that found

in most metropolitan regions elsewhere in the United States.

In 1954 most of the nation’s metropolitan regions were

characterized by the racial domination of white school child

ren both within the central cities and in their traditionally

white suburbs. The implications of this demographic pattern

15

for court-ordered desegregation were far-reaching and ex

tensive.

Although in the subsequent two decades the minority

concentrations would increase universally within central

cities, in 1954 only certain of the nation’s cities had any

appreciable minority representation. However, in 1954, signi

ficant variation could be found in the degree of concentration

between regions and cities; witness, other selected cities ap

pearing in Table I.

TABLE I MINORITY STATUS IN CENTRAL CITY

SCHOOLS 1954

(PER CENT ENROLLMENT IN SCHOOLS)

Atlanta 43.7 Newark 31.0

Baltimore 36.4 New Haven 15.3

Beaumont 33.2 New Orleans 41.6

Buffalo 10.1 New York City 15.2

Charlotte 40.8 Oakland 28.0

Chicago 20.7 Philadelphia 31.2

Cincinnati 30.0 Pittsburgh 21.6

Cleveland 29.1 Richmond 44.1

Dayton 21.9 St. Louis 30.5

Detroit 27.2 San Francisco 20.9

Gary 39.4 Topeka 9.6

Harrisburg 21.3 Trenton 25.2

Hartford 17.1 Washington, D.C. 57.2

Memphis 42.8 Wilmington 27.9

* Representative selection of cities with high minority population

concentrations chosen from the Report of the Commission on Civil

Rights and from Metropolitan Area Statistics. The methodology

employed to derive the data for the year 1954 is outlined in

Table II. In interpreting the data, it is necessary to assume a minority

representation in all schools within each school district which

approximates the percentage level of minority students within the

school district as a-whole. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 25.

The data presented in Table I substantiates that, even in

those metropolitan areas which had high concentrations of

minority school children resident in their central cities, it was

possible in 1954 to establish unitary non-discriminatory school

districts within the central cities.

16

B. The Relevant School Community For Purposes

of Desegregation Is Now Metropolitan, Not Municipal.

Although the relevant school community within which to

dismantle dual school systems was the central school district

in 1954, quite the opposite was true by the end of the decade

of the 1960’s.

The data depicted in Table II, when compared with

Table I, substantiates that, had the courts mandated the

abolition of dual school systems in 1970 solely within existing

central city school districts, the resulting increase in the

number and percent of minority-identified schools would

have produced nothing short of the establishment of a geo

graphically expanded dual system of public schools between

districts in most metropolitan regions.

Over those intervening years from 1954 to 1970, the in

crease in resident white population in central cities subsided

and, from 1960 to 1970, even declined by 600,000. Correlative

decreases in the number of white children attending public

schools in central cities were even greater due to the expanded

enrollment of white children in private schools. In essence,

the numerical and the proportional increase of minority child

ren in central city school systems passed a critical threshhold,

whereby the magnitude of the minority school population in

central cities came to overwhelm the dominant white majority.

The state school boards, having accommodated the initial

increases in the number of white children within suburban

school districts, discouraged further in-migration to the central

cities and, in the process, set the parameters within which

took place the subsequent exodus of young families with

children to the suburbs.

Just as state support of dual school systems shifted from

within, to between school districts, so too, the community of

children harmed by state segregative actions also shifted and

17

TABLE 2 MINORITY STATUS IN CENTRAL CITY

SCHOOLS 1950-1970 * 11

(PER CENT ENROLLMENT IN SCHOOLS)

1 2 3 4

1950 1954 I960 1970

Atlanta 41.1 43.7 43.9 65.7

Baltimore 27.2 36.4 50.1 65.7

Beaumont 33.1 33.2 33.3 40.4

Buffalo 7.6 10.1 29.4 39.0

Charlotte 53.4 40.8 32.4 33.1

Chicago 15.5 20.7 28.5 63.8

Cincinatti 27.9 30.0 33.1 44.9

Cleveland 18.8 29.1 44.5 60.8

Dayton 16.6* 21.9 29.9 43.8

Detroit 16.7 27.2 42.9 64.2

Gary 32.9* 39.4 49.1 73.3

Harrisburg 15.2* 21.3 30.4 20.3

Hartford 15.3 17.1 25.7 64.6

Memphis 41.6 42.8 44.5 50.7

Newark 34.4 31.0 54.2 79.5

New Haven 7.9* 15.3 26.3 56.1

New Orleans 38.4 41.6 46.4 67.3

New York City 14.7 15.2 21.1 53.5

Oakland 26.4 28.0 34.5 66.4

Philadelphia 20.8 31.2 46.7 61.1

Pittsburgh 14.5 21.6 32.2 38.3

Richmond 42.0 44.1 42.0 55.8

St. Louis 18.7 30.5 48.3 59.1

San Francisco 12.9 20.9 32.8 46.4

Topeka 9.2 9.6 10.2 17.4

Trenton 15.4* 25.2 39.8 70.5

Washington, D.C. 43.6 57.2 77.5 94.1

Wilmington 18.2* 27.9 42.5 75.8

* Approximation

Sources: 1. U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population 1950.

Vol. II, Characteristics of the Population, Parts 5, 7, 8, 9,

11, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 30, 32, 33, 35, 38, 42, 43, 45,

Table 34, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1952.

2. Straight line interpolation.

3. U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population:. 1960.

1 2 , 1 5 * 2 4 , 3 2 , 3 4 , 3 5 , 3 7 , 4 0 , 4 4 , 4 5 / 4 7 ,

Tables 73, 77.

U.S. Bureau of the Censusy Census of Population: 1970. .General

Social and Economic Characteristics. Final Report PC(1)-C, 8,

9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 32, 34, 35, 37, 40, 44, 45,

47, Tables 83, 91, 97.

4.

18

expanded geographically to include white suburban school

children.

C. Re-segregation Within the Central City School

Districts Is a Symptom of Regional D e Jure Segregation.

In formulating a remedy in the instant case, involving a

community of children in the Detroit region, the District

Court and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals confronted the

same two basic issues which this Court adjudicated in

Brown I and II. The first issue, that of defining the nature of

the constitutional violation, calls upon the courts to ascertain

the geographic and social extent of state-imposed segregation

of white from minority children. Because de jure segregation

is a dual relation which effects a separation of white from

minority as well as minority from white, the critical dis

tinction for the courts in defining the community of children

harmed, both minority and white, is not the quantitative

enumeration of the visible minority which have been segre

gated from the surrounding white society. To the contrary,

the issue is to distinguish and separate the surrounding white

society into two parts — (1) that part of the white majority

circumscribed by the de jure actions and policies of the state

and (2) that exurban sector of the white majority which is

segregated de facto from the suburban white and the urban

minority. More specifically, the problem the Courts have to

resolve is the identification and separation of those particular

white-dominated schools influenced by state action and which,

therefore, fit into the total pattern of de jure segretation.

With the nature of the constitutional violation defined,

the second major issue, that of practical implementation,

admits of no easy solution. The process of dismantling dual

school systems has been complicated, and in some cases

thwarted entirely, by the shifts which have taken place in the

racial composition of those neighborhoods and schools affected

19

by court orders. This problem has nowhere been more severe

than in the central city school districts. This Court, in Swann,

has acknowledged the difficulties associated with attempts

to establish unitary school systems:

“This process has been rendered more difficult by changes

since 1954 in the structure and patterns of communities,

the growth of student population, movement of families,

and other changes, some of which had marked impact on

school planning, sometimes neutralizing or negating

remedial action before it was fully implemented.”

Swann, 402 U.S., at 14.

In this era of “evolving remedies” subsequent to Brown,

the courts often precipitate demographic change through the

implementation of a remedy which is bounded within too

narrow a geographic area. By not embracing the entire region

in which the process of segregation has taken place when

establishing unitary school systems, the courts run the risk of

increasing the long-run minority concentrations in court-

affected areas through a process of resegregation. The “white

flight” to the suburbs which acts as a parameter and facili

tates resegregation within the central cities is, however,

founded upon a larger underlying pattern of de jure segre

gation.

A rapid transition of a school district from majority-white

status to a preponderance of minority students, such as that

which has taken place in Detroit (See Tables I and II), implies

a relation between minority and majority which traverses and

extends beyond the school district boundaries. The racial

displacement of white with minority students within a central

city school district would not be possible were it not for the

receptive environment created within contiguous suburban

towns which absorb white out-migration. It is only because of

the relative attractiveness created in the suburbs, coupled

with prejudice, that individual household decisions to relocate

20

can combine to produce a total pattern of racial segregation

which is regional.

Such a pattern of out-migration is contingent upon four

factors which support the white exodus and which, obversely,

contain minority households in the central cities: (1) the

higher income levels of white households; (2) the freedom of

social mobility within the larger society; (3) the geographic

proximity of suburb to city to the extent that traveling time

and distance from the new location allows the out-migrant

household to maintain employment and social contacts within

the region, and (4) the existence of new residential and school

construction in the suburbs. The salient and essential charac

teristics common to the out-migrants is that they remain

constituents of the regional economy and society.

D. The Nature of the Constitutional Violation in the

Instant Case Compels the Affirmation and Adoption of a

Metropolitan Remedy.

In order to delineate a pattern of de jure segregation

which is regional, it is necessary to specify state policies and

administrative actions which have separated the whites who

have out-migrated from the minorities remaining in the

central cities. Both the record herein and the data in Tables

I and II indicate that the collective effect of individual

location decisions has been to structure the economic and

social geography of the City of Detroit and its surrounding

region. The record, then, reveals a pattern of regional segre

gation which has two distinct aspects: (1) effective segrega

tion has taken place within the school system of the City of

Detroit, and (2) segregation has increased and continues to

increase between the school system of the City of Detroit

and that of its surrounding suburbs.

The State of Michigan, through its local agent, the Detroit

School Board, has admitted and the Courts have found that,

21

de jure segregation existed within the School District of

Detroit. The State, having admitted to only one aspect of the

regional pattern of de jure segregation, does not thereby limit

the extent of its responsibility for creating inter-district

segregation in the Detroit region.

Over the years since Brown, the School Board of the State

of Michigan and its local agents have undertaken a massive

school construction program, the segregative consequences

of which were known and foreseeable. Over the period from

1954 to the present, well over 400,000 students have been

accommodated in suburban school districts in the Detroit

region6. And from 1967 to the present, the school Boards

in the Detroit region have reported the racial compo

sition of their student body both to the federal government

and to the Michigan State Board of Education7. In light

of these facts, the complicity and active participation of

the School Board of the State of Michigan, in determining the

pattern of segregation within and between districts, cannot

be ignored or denied. The Petitioner’s contention, therefore,

that the nature of the constitutional violation is defined

+6,within, and contained and restricted^ segregative acts of

school authorities within the school district of Detroit, is

transparent and tenuous and should be discarded as being

without basis in fact or in law.

The Respondents reasoned, to the contrary, that in

light of the high and increasing concentrations of minority

children in Detroit’s schools, the pattern of de jure segregation

extended to white schools in the suburban townships and,

therefore, required a metropolitan remedy to assure the

establishment of a unitary school system. At each step of

the progress of the instant case the courts found in favor

of the Respondents and took steps toward the implementation

of an inter-district remedy.

22

Essentially the courts found a pattern of state education

in the metropolitan area which was one of an expanding core

of black schools with a ring of white suburban schools. Again,

the blackness of the schools is directly related to the whiteness

of other schools in the area. The courts simply examined the

entire area affected by the remedy in light of the Swann

limitation of “time and distance” . No governmental structure

has been upset. Rather, state authorities have suggested, and

Respondents agreed, that pupils and staff could be exchanged

by contract (a not unfamiliar governmental arrangement).

The question of redrawing districts when necessary has been

left, just as in reapportionment cases, with the State Legis

lature.

The central and critical issue here is that of student

assignment. In arguments in the record, and in those put

forth by the City of Hartford herein, it has been amply

shown that the nature of the constitutional violation is

regional and is in no way contained solely within the school

district of Detroit. Therefore, this Court can do no other than

uphold and affirm the finding of the Sixth Circuit Court of

Appeals that, in dismantling the dual school system, a

metropolitan remedy is constitutionally required. To do other

wise, and to order a “Detroit-only” solution as has been argued

by the Petitioners, would re-instate, re-establish, and give

sanction to a “ separate but equal” system of schools in the

Detroit region.

IV. THERE IS AN INHERENT AND ESSENTIAL

UNITY BETWEEN THE INTEREST OF CENTRAL

CITIES AND THEIR SUBURBAN TOWNS FORGED

BY DOMINANT LONG TERM FORCES WITHIN THE

ECONOMY.

The structure of metropolitan areas has been formed by

a myriad of factors among which the technologies of modern

production and distribution are probably most significant.

23

Prior to the turn of the century, reliance on horse and

rail transportation, on telegraph and messenger service, on

multi-storied manufactories, and on small-scale retail outlets

combined to contain and circumscribe the limits within which

urban economic activity could efficiently function. Early pro

duction technologies were simple, requiring only a modicum

of land and capital. As new technologies were developed and

integrated, more and larger units of capital were required,

and as a result, the suburbs became relatively more attractive

than the city for the location of new manufacturing activity.

The advent of high rise office buildings simultaneously trans

formed the profile and character of the city.

America entered the 20th century with an industrial

economy which attracted even more activity and greater

numbers of people to its already flourishing central cities. In

the South, Midwest and West these industrial and residen

tial increases were accommodated through the creation and

rebuilding of entire cities; e.g., Atlanta, Phoenix and Los

Angeles. As manufacturing activity continued its growth,

these cities faced the identical space constraints endemic to

the older, Northern urban areas. The density of industrial

activity within all cities reached critical levels and spilled

over existing city boundaries. Suburbs became the necessary

adjuncts to the industrial activity situated within the cities

of metropolitan areas throughout the nation.

This new structural balance in metropolitan areas al

tered the functional relationship between city and suburb. As

new manufacturing enterprises were accommodated in the

land-rich suburbs, central cities expanded their role as the

regional base for corporate headquarters, financial institu

tions and the various other professional services required in

the movement of goods from their point of production to their

final destination. The re-allocation of economic activity be

tween city and suburb was accompanied by greater economic

24

efficiency and higher levels of productivity. A synergistic

effect was created wherein producers, although locationally

discrete and physically removed from all others, became in

creasingly interdependent in order to meet the needs of

regional residents and the demands of national and inter

national markets.

The hegemony of the central city declined as the level of

regionwide economic activity increased. These changes were

reflected by a shift in regional commutation patterns and a

marked increase in the degree of interaction between city and

suburb. Town lines in the metropolitan complex were being

traversed not only by suburban commuters working in the

central city, but by city residents as well, seeking the employ

ment opportunities offered within the suburban ring.

A. Developments in Technology and the Economy

Accelerated Suburban Residential Growth.

While technological changes were transforming the spa

tial allocation of production activities, a metamorphosis in

the pattern of residential land use was taking place as well.

Prior to the turn of this century, American society was an

amalgam of rural and urban places. The suburbs had not yet

developed to significant proportions and, consequently, the

majority of metropolitan area residents lived and worked in

the central city. Technological developments in the early part

of the century, however, soon altered this pattern. The ubiq

uity of the private automobile, telephone, and television en

abled individuals to live at increasingly distant locations from

their places of employment, recreation, and shopping, while

continuing to interact with the central city. The inexpensive

land in rural and suburban areas, coupled with easily obtained

mortgages, and the rising income levels generated by the

increasingly productive metropolitan economy, allowed fam

ilies to enjoy less crowded living quarters than those available

to urban residents.

25

In the post World War I period, the accelerating demand

for low-density residential housing quickly outstripped the

available supply of land within the city boundaries. During

this period of expansion, the ability of the city to annex con

tiguous residential areas was precluded by the existence of

political boundaries. Where boundaries did not previously ex

ist, the new suburban expansion necessitated their creation.

In other cases, existing rural towns near the city were simply

engulfed by residential development. The result was an eco

nomically integrated metropolitan region fragmented by a

variety of jurisdictional lines.

B. The Increasingly Complex Socio-Economic In

terlock Between City and Suburbs Altered the Balance

Between the Interests of Individual Communities and

Those of the Larger Metropolitan Region as a Whole.

In the early period of suburbanization, the suburban

towns were distinct communities, each with its own particular

flavor and, as a group, decidely different in structure and

function from the central city. The undeveloped open spaces

and the strictly residential character of most of these towns

created a life style altogether different from that of their ur

ban counterparts. Their governmental structures were

simpler, their finances less complicated, and their problems

primarily local community issues easily resolved with active

participation by all interested parties. During this formative

period, while each unit of the metropolitan community evol

ved and extended its own local identity, the central city re

mained the nexus of all intercommunity activity — economic

political, social, cultural and educational — and thus em

braced and represented the metropolitan identity.

As the technological shifts and economic exigencies gave

impetus to the urbanization of the suburbs, the residents of

the suburban towns and their representative governments

26

were confronted with the problems of resolving the multi

faceted issues arising from the existence of large industrial

and commercial establishments within their jurisdictions. The

regional interlock of these large firms, resulting from their

employment of workers and their purchase of supplies from

firms in other metropolitan towns, as well as their use of ser

vices located in the central city, forced a shift in the scope of

local decision-making away from local autonomy and towards

regionalism.

C. Metropolitan Community of Interest Was Legit

imized and Made Formal by Private Citizens and All

Levels of Government.

As the city and its suburbs evolved into an economically

integrated region, narrowly defined parochial interests could

no longer dominate the thinking of community leaders. The

shift towards metropolitanism, as above described, was a

result of increasing regional interlock and growing similari

ties in the economic and social structure of city and suburb.

This growing community of interest has manifested itself in

the increasing number of co-operative agreements entered

into by both the representative bodies and administrative

agencies of these municipalities and by private citizens alike.

The following are examples of the institutionalization of the

regional community of interest (See Appendix III).

LOCAL:

1. The municipal governments of suburbs and cities

have created numerous authorities to provide public ser

vices on a regionwide basis in such areas as planning,

public health, public safety, mass transit, water and

sewer systems, as well as in special educational services;

and

2. Private citizens of these communities have set

up co-operative agencies to meet the diverse needs of

27

regional residents. Chambers of commerce, councils of

churches, centers for the treatment of drug abuse and

alcoholism, and sundry other business and social service

organizations are examples of these private and non

profit co-operative institutions.

Parallel to these changes, officials at state and federal

levels have recognized the community of interest between

city and suburb by assigning regional bodies the responsibility

for carrying out, and the authority for overseeing, the ad

ministration of a variety of State and Federal programs.

STATE:

1. The creation of state administrative districts with

in regions in order to facilitate governmental functions

adheres to the intrinsic unity of city and suburb. Judicial

districts, environmental regions, welfare districts, police

units, tax districts, and civil defense areas are exemplary

of these administrative districts.

2. State-approved and funded regional planning

agencies, which exist in every state in the nation, are

assigned the responsibility for coordinating growth and

for providing public planning services within their

jurisdictions.

FEDERAL:

1. The central city and its surrounding region, be

cause they are viewed as an important socio-economic

unit, constitute the main focus of much of the statistical

activity of the federal government. The two major geo

graphical loci of information-gathering are the Standard

Metropolitan Statistical Area of the Bureau of the Census

and the Labor Market Area of the Bureau of Labor

Statistics, both of which are defined on the basis of

2 8

interaction between central city and its contiguous area.

Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area is defined by

the Bureau of Census as containing one or more central

cities with a combined population of at least 50,000

inhabitants, and with contiguous towns in “the region

which are socially and economically integrated with the

central city.”8

2. Metropolitan regions, because they have evolved

to the point wherein they are functionally unified, are

eligible for, and are prime targets of, federal funds for

economic development. Most outstanding among these

are the HUD 701 Comprehensive Planning Grants,

Economic Development Agency Grants and Manpower

Administration Training Funds.

Not only has the Federal government recognized the

economic and social community of interest between city and

suburb through numerous economic development grants, but

it has also explicitly acknowledged the metropolitan di

mension of the racial isolation of central city school children.

The 92nd Congress of the United States appropriated sub

stantial public funds under Title VII of the Educational

Amendments of 1972 for the purpose of “dealing with con

ditions of segregation by race in the schools of local education

al agencies of any State without regard to the origin or cause

of such desegregation” (20 U.S.C.A. § 1602). Provision has

been expressly made for the joint development, by a group of

local educational agencies located in a Standard Metropolitan

Statistical Area, “of a plan to reduce and eliminate minority

group isolation, to the maximum extent possible, in the public

elementary and secondary schools in the SMSA.” (20 U.S.C.A.

§ 1608).

29

D. The Growth Of Metropolitan Areas Has Been

Subverted By Divisive Forces.

During this century, the cities and suburbs in the nation’s

metropolitan areas have experienced an unprecedented eco

nomic growth predominantly influenced and shaped by the

forces of a new technology. The essential unity between the

interests of central cities and their suburban towns has been

forged by these salutary economic trends.

Since 1954, however, an ominous and antagonistic social

force, has surfaced to disrupt and stifle the heretofore pre

vailing forces of a progressive economy. This unsettling force

is, significantly, the pattern of population shifts caused by the

effects of school segregation and school district fines on res

idential location. The complicity of state school authorities

in giving shape to this antagonistic force is amply recited

above.

The balance between city and suburb has been adversely

affected by the accelerated out-migration of white families

and economic activity in the post Brown I era. The combined

cumulative effect of the location decisions of people and

business have led to rising social and economic costs both in

the suburbs and the city. The sprawling overdevelopment of

the suburbs stands in contrast to the disinvestment, poverty

and virtual bankruptcy of urban governments engulfing the

cities in an inexorable spiral of decay.

It is noteworthy, however, that what began as a mere

disruptive influence has now come to threaten and subvert

the equilibrium and unity between city and suburb to the

point where it will corrode and blight the body politic of our

metropolitan areas.

30

CONCLUSION

In light of the foregoing, we respectfully urge this Court

to affirm the decision of the en banc Sixth Circuit Court of

Appeals as the only sound, feasible and effective course to

meet the controlling standards established by Brown I and II.

The nature and scope of the remedy are defined by the nature

and scope of the injury. It is impossible, in any meaningful

sense, to desegregate a racially homogeneous, large core-city

school district such as Detroit or Hartford, The empirical

realities compel a regional remedy to redress an essentially

regional harm to both white and nonwhite students.

The insular course advanced by the Petitioners is not a

proper judicial corrective. A “Detroit-only” remedy cures

nothing. It contravenes the Brown mandate by invidiously

polarizing the races. Indeed, it well exacerbates and accentu

ates the proscribed dual system by resegregation. Above all,

it ineluctably portends a 100% minority “unitary” Detroit

school district.

If such narrow remedy were adopted and followed, it

would dilute, if not nullify, the great desegregation principal!

enunciated by this Court since 1954. It would revive the

discredited “separate but equal” doctrine and, ironically,

recreate and re-establish within our core-cities the very sepa

rate and unequal system of public education long outlawed

by this Court. In short, the intra-district remedy represents a

regression to the dead doctrines and rigid provincialism of the

of the Nineteenth Century. If the federal courts are restricted

in providing an adequate remedy for a federal wrong by

virtue of state law, we will have returned not to the Consti

tution but to the Articles of Confederation.

We ask this Court to fashion an inter-district plan of

student assignment wholly consistent with the existing spec

trum of federal, state and local laws prescribing and approving

31

governmental policies and programs on a regional basis.

Having encouraged and reaped the gains of regional growth

and development, the State and its suburban surrogates cannot

tenably claim that school districts are unrelated and inde

pendent of one another. Such facile rationalization cannot be

used to circumvent their clear responsibilities to eliminate

racial discrimination in public education. It ill behooves those

who have profited from the new regionalism to repudiate the

city — the source of their profits — by suggesting that the

city look to itself for its own remedy. It is indefensible that

Petitioners now assume a righteous posture, insensitive to the

segregated plight and loss of the urban and suburban school

child — a plight and loss which they helped to create and

sustain.

The public school children of the metropolitan Detroit

and Hartford regions, of whatever race or circumstance, must

in fact be guaranteed the equal educational opportunity to

know and achieve the society of their peers and, in turn, the

respect for and understanding of themselves and others. Thus,

will their legal rights be secured, their human dignity be

maintained, and the true meaning and purpose of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment be fullfilled.

Thus, can this Court alone, in its commanding power and

wisdom, secure such rights, maintain such human dignity and

fullfill such meaning and purpose of the Constitution of the

United States.

Respectfully submitted,

A lexander A. Goldfarb

Corporation Counsel

for the

City of Hartford

550 Main Street

February 1, 1974 Hartford, Connecticut

la

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO APPENDIX

Page

I. NOTES TO TEXT .......................................................... 2a

II. STATISTICAL TABLES

A Racial Census-Hartford Public Schools,

1965 to 1972 ............................................................... 6a

B Racial Segregation in Hartford Public

Schools, 1965-1972.......................................................7a

C Minority Population In Central Cities

(1950-1970) ............................................................... 8a

D National Population Trends For Metropolitan

Areas, 1950-1970 ....................................................... 9a

E Income Characteristics In 1969 And 1959

Of Families By Sex And Race Of Head

And Metropolitan Residence: 1970 And 1960 ...... 10a

F Distribution Of Persons Below The Poverty

Level In 1969 And 1959 By Race And

Metropolitan Residence: 1970 And 1960 ............... 11a

G Employment In All SMSA’S And Central

Cities, 1958 and 1967 ................................. 12a

III. HARTFORD REGION AS AN EXAMPLE OF

COMMUNITY INTERLOCK WITHIN A

METROPOLITAN REGION........................................... 13a IV.

IV. FOOTNOTES TO APPENDIX 19a

2a

NOTES TO TEXT

“As a result of the population shifts of the post-war period,

concentrating the more affluent parts of the urban population in

residential suburbs while leaving the less affluent in the central

cities, the increasing burden of municipal taxes frequently falls

upon that part of the urban population least able to pay them.

Increasing concentrations of urban growth have called forth

greater expenditures for every kind of public service education,

health, police protection, fire protection, parks, sewage disposal,

sanitation, water supply, etc. These expenditures have strikingly

outpaced tax revenues.”

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders, Chairman Otto Kerner (1968) p. 393

“The central cities, particularly those located in the industrial

Northeast and Midwest, are in the throes of a deepening fiscal cri

sis. On the one hand, they are confronted with the need to satisfy

rapidly growing expenditure requirements triggered by the rising

number of “high cost” citizens. On the other hand, their tax re

sources are increasing at a decreasing rate (and in some cases

actually declining), a reflection of the exodus of middle and high

income families and business firms from the central city to sub

urbia.”

Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, "Urban

and Rural America: Policies for Future Growth” , A-32, p. 26

“The income disparity between central city and suburban fam

ilies has increased during the past decade. In 1959, the median fam

ily income for central city families ($7,420) was about $930 less

than that for suburban families ($8,350). By 1969, about $1,850

separated the median family incomes for these two groups ($9,160

and $11,000, respectively). The median income of central city

families decreased from 89 percent of that of suburban families in

1959 to about 83 percent in 1969.”

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series

P-23, No. 37, “ Social and Economic Characteristics of the Pop

ulation in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas: 1970 and

1960” , P (23) No. 37, p. 2.

1 .

2.

“The number of Negroes residing in suburban rings has in

creased by about 1.1 million persons during the decade. However,

the proportion of the metropolitan Negro population living in sub

urban rings has not increased significantly between 1960 and 1970,

remaining at about one fifth. Negroes comprised only about 5 per

cent of the suburban population in 1970.”

Ibid, p. 2.

“Thousands of Negro families have attained incomes, living

standards, and cultural levels matching or surpassing those of

whites who have “upgraded” themselves from distinctly ethnic

neighborhoods. Yet most Negro families have remained within pre

dominantly Negro neighborhoods, primarily because they have been

effectively excluded from white residential areas.”

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders,

Chairman Otto Kerner, (1968) at 244.

“Negro families continue to have incomes far below those for

white families. In 1969, the median income for Negro families in

metropolitan areas was $6,840 compared to $10,650 for their coun-

3a

terparts. The comparable figures for 1959 were $4,770 and $8,200,

respectively. Even though the ratio of Negro to white family in

come increased from 58 percent in 1959 to about 64 percent in 1969,

the dollar difference between their respective medians has increased

from $3,430 in 1959 to 3,810 in 1969.”

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series

P-23, No. 37, “ Social and Economic Characteristics of the Pop

ulation in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas: 1970 and

1960” , P(23) No. 37, p. 2.

“While the proportion of the total metropolitan population liv

ing in central cities decreased during the past decade, to a point

where the majority (56 percent) of metropolitan residents now live

in suburban areas, the metropolitan poverty population has re

mained concentrated in central cities. About five-eighths of the

metropolitan poor lived in central cities in both 1959 and 1969.

“The poverty rates for both white and Negro persons have de

creased in all residence categories between 1959 and 1969. How

ever, the poverty rates for Negroes continue to be significantly

higher than those for white persons. In metropolitan areas, the pov

erty rate for white persons was about 7 percent compared to 24

percent for Negroes in 1969. Outside metropolitan areas, the poverty

rate for whites was about 14 percent, while about half of Negroes

were poor. In central cities, about one in ten white persons was poor,

in 1969, as compared to one in four for Negroes. In suburban areas,

the poverty rate for whites was about 5 percent, while the rate for

Negroes was not significantly different from that in central cities.”

Ibid, p. 7.

“ In large part, the separation of racial and economic groups

between cities and suburbs is attributable to housing policies and

practices. The practices of private industry — builders, lenders,

and real estate brokers — often have been key factors in excluding

the poor and the nonwhite from the suburbs and confining them to

central cities. Practices of the private housing industry have been

rigidly discriminatory, and the housing it has produced — largely

in the suburbs ■— has been at a price that only the relatively afflu

ent can afford.”

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, A Report: Racial Isolation in

the Public Schools, (1967) p. 20.

“Private industry is not alone responsible, however, for the

growth of virtually all-white, middle-class suburbs surrounding the

urban poor. Government at all levels has contributed to the pattern.

“In addition, the authority of local government to decide on

building permits, building inspection standards, and the location of

sewer and water facilities, has sometimes been used to discourage

private builders who otherwise would be willing to provide housing

on a nondiscriminatory basis.”

Ibid, p. 21.

3.

“The rich variety of the Nation’s urban population is being

separated into distinct groups, living increasingly in isolation from

each other. In metropolitan areas there is a growing separation

between the poor and the affluent, between the well educated and

the poorly educated, between Negroes and whites. The racial, eco

nomic, and social stratification of cities and suburbs is reflected in

similar stratification in city and suburban school districts.”

Ibid, p. 17.

4a

“Thus there is a parallel between population and school enroll

ment trends within metropolitan areas. In both cases, Negro pop

ulation increases are almost entirely absorbed in the central cities.

In both cases, the isolation of Negroes in residential ghettos and

Negro schools is growing. The Nation’s Capital — Washington, D.C.

— already has a majority-Negro population. Other cities are expe

riencing rapid increases in Negro population. City school enroll

ments more sharply reflect the trend. A substantial number of cities

have elementary school enrollments that already are more than

half Negro. In these cities, at least, the problems of racial isolation

in the schools can no longer fully be met in the context of the city

alone.’’

Ibid, p. 13.

“The causes of racial isolation in city schools are complex and

the isolation is self-perpetuating. In the Nation’s metropolitan areas,

it rests upon the social, economic, and racial separation between

central cities and suburbs. In large part this is a consequence of the

discriminatory practices of the housing industry and of State and

local governments.”

Ibid, p. 70.

4.

“Although residential patterns and nonpublic school enrollment

in the Nation’s cities are key factors underlying racial concentrations

in city schools, the policies and practices are seldom neutral in

effect. They either reduce or reinforce racial concentrations in the

schools.”

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, A Report: Racial Isolation in

the Public Schools, (1967) p. 39.

“Although purposeful school segregation resulting from legal

compulsion or administrative action is not often found now in the

North, apparently neutral decisions by school officials frequently

have had the effect of reinforcing the racial separation of students,

even where alternatives were available which would not have had

that result.”

Ibid, p. 44.

5.

“While the majority of both the white and Negro populations

resided in metropolitan areas in 1970 (64 percent and 71 percent,

respectively), they exhibited widely different residence patterns.

The white metropolitan population was largely suburban (60 per

cent), while their Negro counterparts were primarily residents of

central cities (78 percent). The white population in central cities

has, in fact, decreased by about 2.6 million during the past decade.

For the white population in central cities, children under 13 years

old and adults between the ages of 25 and 44 years were the major

age groups which lost population between 1960 and 1970 (Table 1).

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series

P-23, No. 37, “ Social and Economic Characteristics of the Pop

ulation in Metropolitan Areas.” 1970 and 1960,” 1971 p. 2.

6 .

U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population, 1950, Vol. II.

Characteristics of the Population, Part 22, Tables 34, 42. U.S. Bureau

of the Census, Census of Population: 1970. General Social and

Economic Characteristics, Final Report PC(1) 24, Tables 83, 120.

7.

Report Required by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and by

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Section 80.6(b) of

5a

HEW Regulations (45 CFR 80) issued to carry out the purposes of

Title VI of Civil Rights Act (20 USCA $ 1609; 42 USCA 2000 (d).

8.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population: 1970 General

Social and Economic Characteristics, Final Report PC(1)-C8 Con

necticut. Page App.-4.

6a

TABLE A RACIAL CENSUS - HARTFORD PUBLIC SCHOOLS

An Eight-Year Comparison

(1965-1972) of Minority-

Students*

SCHOOL 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972

Arsenal 99 .3 99 .4 99 .5 99..4 99 .2 99,.7 99.,4 99,.4

Barbour 96 .2 95..7 97 .0 95,.6 97 .0 97..5 97,.1 99 .4

Barnard/Brown 98,.0 98 .5 98 .8 99..3 99 .5 99,.6 99 .0 99 .5

Batchelder 6,.2 6..2 8,.2 14..7 15..0 13,.6 21,.2 24 .2