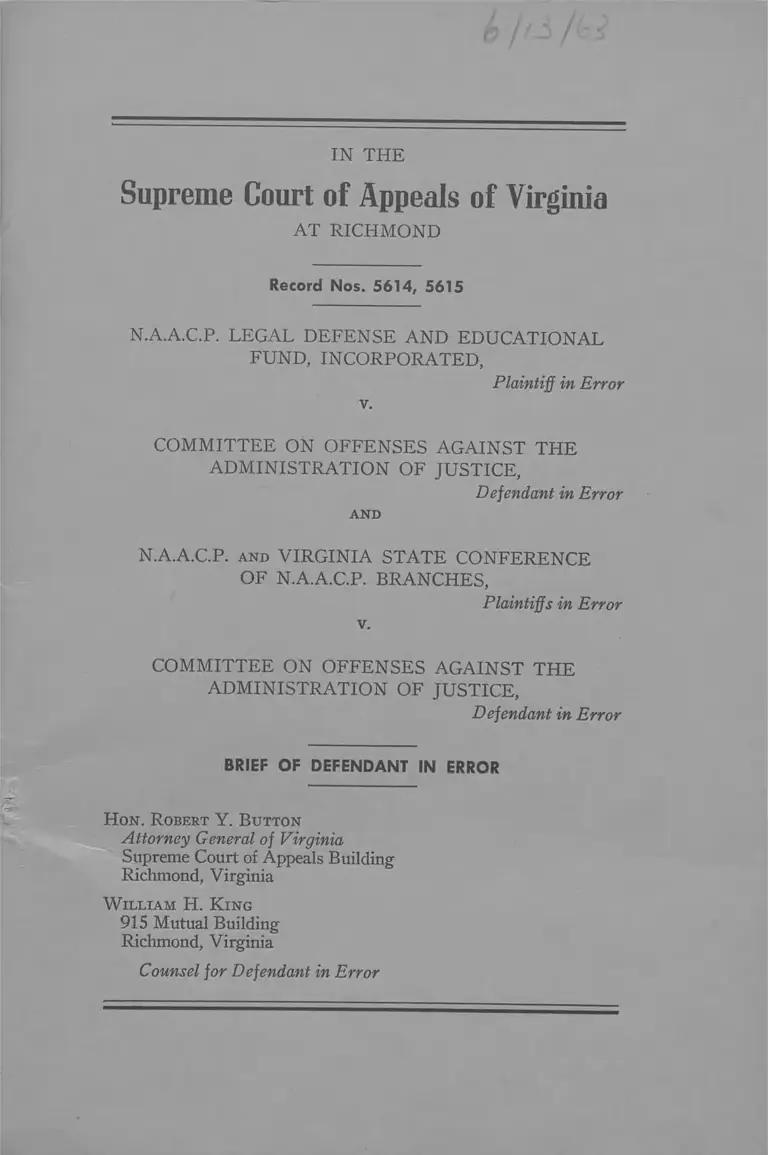

NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Brief of Defendant in Error

Public Court Documents

June 12, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Brief of Defendant in Error, 1963. 2ffd5134-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/795bbe3e-f3de-441a-952c-18505474d4ea/naacp-v-committee-on-offenses-against-the-administration-of-justice-brief-of-defendant-in-error. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

A T RICHMOND

Record Nos. 5614, 5615

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED,

v.

Plaintiff in Error

COM M ITTEE ON OFFENSES AGAIN ST THE

AD M IN ISTRATIO N OF JUSTICE,

Defendant in Error

AND

N.A.A.C.P. an d VIRGIN IA STATE CONFERENCE

OF N.A.A.C.P. BRANCHES,

Plaintiffs in Error

v.

COM M ITTEE ON OFFENSES AGAIN ST THE

AD M IN ISTRATIO N OF JUSTICE,

Defendant in Error

BRIEF OF DEFENDANT IN ERROR

H o n . R obert Y. B u tton

Attorney General of Virginia

Supreme Court of Appeals Building

Richmond, Virginia

W il l ia m H . K in g

915 Mutual Building

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel for Defendant in Error

S t a t e m e n t of t h e C ase a n d of t h e P o in ts I n v o l v e d ......... 2

S t a t e m e n t of t h e F a c t s .......................................................... 3

A rg u m en t .............................................................................. g

I. Section 30-42(b) of the Code Clearly Authorizes the

Interrogatories .................................................................. g

II. The Interrogatories Clearly State the Purpose of the

Committee’s Investigation and the Relevancy of the

Information Sought .................................................... 9

III. Answering Interrogatory 1(a) Will Not Deny the

Movants or Their Contributors Their Rights of “ Free

dom of Association” or Rights of “ Property” ............... 10

IV. The Committee Seeks the Names of Contributors in

Keeping with a Valid Legislative Purpose....................... 11

V. Evidence Was Properly Excluded by the Lower Court 19

VI. No Inquiry May Be Made Into Motives Prompting the

Committee’s Creation, Nor Motives Prompting Its In

vestigation ................................. 21

VII. Other Matters Advanced by the Plaintiffs in E rror..... 24

(a) Equal Protection........................................................ 24

(b) Constitutionality of Section 58-84.1 ........................ 24

(c ) The Attorney General’s Representations in Harri

son v. N.A.A.C.P................. .................................... 25

C o n clu sio n ............................................................................. 26

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

American Communications Associations v. Douds, 339 U S 382

94 L. Ed. 925 (1950) .......................................................’ 12

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Page

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 4 L. Ed. 2d 480 (1960)

11, 14, 17,

Burch v. Grace Street Bldg. Corp., 168 Va. 329, 191 S. E. 672

(1937) ........................................................................................

Communist Party v. S.A.C. Board, 367 U. S. 1, 6 L. Ed. 2d 625

(1961) ..._.................................................................. .................

Daniel v. Family Security Life Insurance Company, 336 U. S.

220, 93 L. Ed. 632 (1949) ........................................................

Fletcher v. Peck, 6 Cranch 87, 3 L. Ed. 162 (1809) .................

Gange Lumber Co. v. Henniford Co., 185 Wash. 180, 53 P. 2d

743 (1936) .................... ..................- ............................... ........

Gibson v. Florida Investigation Committee, 372 U. S. 539, 9 L.

Ed. 2d 929 (1963) .............................................................. 11,

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464, 93 L. Ed. 163 (1948) .........

Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries and W. Co., 251 U. S. 146,

64 L. Ed. 194 (1919) ...............*................. ..............................

Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. Ed. 1152 (1959)

Hubbard v. Mellon, 5 Fed. 2d 764 (D.C. Cir. 1925) .................

Louisiana, ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366 U. S. 293,

6 L. Ed. 2d 301 (1961) ..................................................... 11,

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. (17 U. S.) 316, 4 L. Ed.

579 ................................................................................. _ ......

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1488

(1958) .............................................. .................... 10, 14, 20,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 9 L. Ed. 2d 405 ...............

N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee, 199 Va. 665, 101 S. E. 2d 63 (1958)

N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee, 201 Va. 890, 114 S. E.2d 721 (1960)

N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison, 202 Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55 (1960) 5

a

20

27

13

23

22

18

13

23

22

25

17

16

10

26

6

22

24

i, 9

New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63, 73 L.

Ed. 184 (1928) ......................................................................... 12

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479, 5 L. Ed. 2d 231 (1960)

11, 15, 18

Shenandoah Lime Company v. Governor, 115 Va. 865, 80 S. E.

753 (1914) ................................................................................ 21

Telephone Company v. Newport News, 196 Va. 627, 85 S. E.

2d 345 (1955) .................................................................... 21, 22

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U. S. 367, 95 L. Ed. 1019 (1951) .... 23

Uphaus v. Wyman, 360 U. S. 72, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1090 (1959) 12, 13

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178, 1 L. Ed. 2d 1273

(1957) ............................................. 23

Other Authorities

Constitution of the United States:

Amendment X IV ............................................................... 3

Constitution of Virginia:

Section 11 ............................................. 3

Section 12 ..................... 3

Acts of Assembly, 1956 Extra Session:

Chapter 31 ......................................................... 25

Chapter 3 2 .................................................................................. 25

Chapter 3 3 ..................................................................... 25

Chapter 3 4 ....................................... 20

Chapter 3 6 ................................................... 25

Chapter 37 .......................................................................... 20, 21

Acts of Assembly, 1958:

Chapter 373 ...............................

Hi

Page

21

Page

Code of Virginia:

Section 30-42(b) ............

Section 54-44 ....................

Section 58-81 (m ) (2) .....

Section 58-84.1 ........ ........

Rules of Court 5:1, Section 4 .

Annotation, 103 A. L. R. 513

2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 24

............. .............. 9

....................... 6, 25

........... 6, 8, 24, 25

25

18

iv

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

A T RICHMOND

Record Nos. 5614, 5615

N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INCORPORATED,

Plaintiff in Error

v.

COM M ITTEE ON OFFENSES AGAIN ST THE

ADM IN ISTRATION OF JUSTICE,

Defendant in Error

AND

N.A.A.C.P. an d VIRG IN IA STATE CONFERENCE

OF N.A.A.C.P. BRANCHES,

Plaintiffs in Error

v.

COM M ITTEE ON OFFENSES AGAIN ST THE

AD M IN ISTRATIO N OF JUSTICE,

Defendant in Error

BRIEF OF DEFENDANT IN ERROR

These two cases having been heard together in the

Hustings Court of the City of Richmond, the resulting

records are virtually identical. Because of this, and consid

ering it a matter of convenience to the Court, we have

prepared and filed but one brief in response to those of

the several plaintiffs in error.

2

W e will hereinafter refer to the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People as the “ N.A.A.

C.P.,” to the Virginia State Conference of N.A.A.C.P.

Branches as the “ Conference,” and to the N.A.A.C.P.

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Incorporated as

the “ Fund.” Also, at times we will refer to these three

parties together as “ movants,” that being a designation

they assigned themselves in the court below. The Com

mittee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice

will be referred to as the “ Committee.” References to

pages of the brief of the Fund will be indicated as (F ..... ),

references to the pages of the joint brief o f the N.A.A.

C.P. and the Conference will be indicated as (N ..... ), and

references to pages of the printed record will be indicated

as (R ......).

STA TE M E N T OF TH E CASE AND

OF TH E POINTS IN V O L V E D

The Fund’s statement of material proceedings in the

lower court is accurate. However, the several statements

made by the appealing parties of the questions involved

are exceedingly diverse; and, especially in the case of the

Fund, beg the question.

Accordingly, we here state briefly what we consider

the basic questions involved:

1. Did Section 30-42(b ) o f the Code o f Virginia

authorize Interrogatory No. 1(a) ?

2. Did the Interrogatories sufficiently inform the

movants of the purpose for which the answers were

requested, and the purpose of the Committee’s inves

tigation ?

3

3. Will the answering of Interrogatory No. 1 (a )

violate movant’s rights of “ freedom of association”

or rights in “ property” guaranteed by Sections 11

and 12 of the Constitution of Virginia and by the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States?

4. Did the trial court err in excluding certain evi

dence as being either “hearsay” or “ irrelevant” ?

STATEM EN T OF TH E FACTS

The statements in the movants’ briefs respecting the

purposes of the N.A.A.C.P.,the Fund, and the Conference

substantially accord with the evidence. Most of their

other statements of fact are, however, based upon hearsay

evidence stricken by the trial court. Moreover, their state

ments based on evidence which was admitted contain

numerous unwarranted inferences. Because of this we

recite, in correct perspective, those facts shown by the

evidence.

Stated simply, Section 30-42(b ) of the Code of V ir

ginia provides that the Committee investigate the manner

in which the laws of the Commonwealth relating to its

income and other taxes are being observed by those who

seek to promote or support litigation to which they are not

parties, contrary to law. Pursuant to this provision, the

Committee issued the following interrogatories to the

plaintiffs in error:

“ 1. (a ) State the name and address of each resi

dent of Virginia and of each firm, corporation and

enterprise situated or doing business therein who or

which, since December 31, 1957, has made a donation

of $25.00 or more to the Legal Defense Fund;

4

“ (b ) State the time and the amount of each such

donation.

“ 2. (a ) State the name and address of each recip

ient of sums paid by the Legal Defense Fund since

December 31, 1957 for legal services rendered it or

any other in the Commonwealth of Virginia; and

“ (b ) State the time and the amount of each such

payment, and the nature of the services for which

each payment was made.

“ The word ‘donation’ as used in interrogatory

No. 1 shall be deemed to include, but shall not be lim

ited to, each payment of $25.00 or more received by

the Legal Defense Fund as a membership charge or

fee, it being understood that the Legal Defense Fund

in answering the interrogatory is not required to

state the purpose of any donation.

“ These interrogatories are propounded pursuant

to §30-42(b) of the Code of Virginia, and answers

thereto are required to aid the Committee in deter

mining what donors, if any, have wrongfully record

ed their donations as allowable deductions in their

income tax returns filed with the Commonwealth of

Virginia, and what recipients, if any, have wrong

fully failed to show as income in such returns fees

for legal services rendered in the Commonwealth of

Virginia.” (R. 8)

Although the interrogatories we have quoted are ad

dressed to the Fund, interrogatories directed to the N.A.

A.C.P. and to the Conference are identical excepting only

that their names were appropriately substituted for that

of the Fund, and the year designated in questions 1(a)

and 2 (a ), was changed to “ 1956” rather than “ 1957.”

It is indeed significant that the Fund fully answered

Interrogatories 1 (b ) , 2(a) and 2(b) (R. 17-23), yet the

N.A.A.C.P. and the Conference answered nothing. Ac

5

cordingly, the Fund has moved to quash only Interroga

tory 1 (a ), while the N.A.A.C.P. and the Conference have

moved to quash the interrogatories in their entirety.

Due to the particular attention directed to Interroga

tory 1 (a ), it is appropriate to consider those laws and

facts which make clear the propriety of the information

there sought.

The pertinent statute under which the Committee pro

pounded its interrogatories to the plaintiffs in error is

Section 30-42(b ) of the Code of Virginia, which pro

vides :

“ (b ) The joint committee is further authorized

to investigate and determine the extent and manner

in which the laws of the Commonwealth relating to

State income and other taxes are being observed by,

and administered and enforced with respect to, per

sons, corporations, organizations, associations and

other individuals and groups who or which seek to

promote or support litigation to which they are not

parties contrary to the statutes and common law per

taining to champerty, maintenance, barratry, run

ning and capping and other offenses of like nature.”

It is clear that an unauthorized practitioner directing

or controlling litigation is guilty of “ other offenses” speci

fied in this Section. In N . A . A . C . P e t al. v. Harrison,

202 Va. 142, 155-157, 116 S. E. 2d 55 (1960), this Court

found that the movants were engaged in the unauthorized

practice of law. This finding was not reversed on the ap

peal taken to the Supreme Court of the United States,

that Court limiting its decision to a finding that these

organizations were not improperly soliciting legal busi

ness for those lawyers forming their respective staffs.

6

See, N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 9 L. Ed. 2d

405 (1963).

That contributors to the Fund, or the N.A.A.C.P., or

the Conference are “ persons” who “ support” litigation to

which they are not parties cannot be denied. Among ac

knowledged purposes of these organizations is the support

of litigation (see Exhibits 1, 2, 3, D and E ). Indeed, the

support of litigation is the primary purpose of the Fund,

according to the testimony of its former Director and

Chief Counsel, now Judge Thurgood Marshall (R. 70).

And W . Lester Banks, Executive Secretary of the Con

ference, gave like testimony concerning the support of

litigation by the N.A.A.C.P. and the Conference (R . 80-

81). Also these organizations state that their work is

financed entirely by contributions and “ membership fees”

which are in the nature of contributions (see Exhibit 6,

p. 67, and R. 70-71). It necessarily follows, therefore,

that an individual who contributes funds to an organiza

tion for use in its program of litigation is “ supporting”

litigation within the terms of Section 30-42(b ) of the

Code o f Virginia.

Further, no person making a contribution to any of

the plaintiffs in error may deduct such contribution in

computing income taxes payable to the Commonwealth of

Virginia. Such deduction is prohibited by Section 58-84.1

and Section 58-81 (m ) (2 ) of the Code of Virginia.

The movants have contended that information as to

whether such deductions have been improperly made can

be obtained by the Committee from information within

the knowledge of the Department of Taxation of V ir

ginia. However, as testified by Mr. Edgar G. Hobson of

that Department, it would take the 26 members o f the

7

staff of his office two years to audit the returns involved

here (R. 107-108). Although admittedly a full audit

would not be necessary to check the deduction items of the

returns, each return would have to be individually exam

ined since all returns are filed together without regard

to whether the short or long form is used (R. 113). Mak

ing the gratuitous assumption that the returns could be

checked for deductions at the rapid rate of 120 per hour,

it would take approximately 42,000 man hours to check

the 5,000,000 returns on hand from 1957 to the time of

the interrogatories. At a pay rate of but one and three-

fourths dollars per hour, therefore it would cost the Com

monwealth of Virginia more than $70,000 to do what

movants have suggested the Committee undertake as an

alternative to the present interrogatories.

The plaintiffs have asserted that their disclosing to the

Committee the names of those who contribute more than

$25.00 in any one year would cause such contributors to

suffer economic reprisals and other harm. The evidence

before the lower court did not support this assertion. Al

though on the hearing below there appeared local and

national leaders of the N.A.A.C.P. and the Fund, includ

ing the Executive Secretary of the Conference (R. 77),

the President of a local branch of the N.A.A.C.P. and a

former member of the Executive Board, Vice-President,

and President of the Conference (R. 104), and the Na

tional Director and Chief Counsel of the Fund (R. 68),

not one of these could testify to ever having himself suf

fered any reprisal or other harrassment by reason of his

known association with the N.A.A.C.P. or the Fund. The

movants did produce one witness, Sarah Patton Boyle of

Albemarle County, Virginia, and a member o f the white

8

race, who testified that she had worked actively in the

white community on behalf of the N.A.A.C.P. and as a

result had been given “ deep freezes” by her social ac

quaintances (R. 100). She also testified that “ threats” did

not bother her (R. 103).

However, the full answer to this assertion of “ fear” of

economic and other harm was given by the testimony of

Senator Joseph C. Hutcheson, Chairman of the Com

mittee. Senator Hutcheson testified that the Rules of the

Committee make private all information obtained through

its investigations, that such information is not made pub

lic, and that it is only released to proper lawful authorities

in those instances where wrongs had been committed (R.

116-117). Thus, any disclosure to be made by the Com

mittee as a result of information given it in response to

Interrogatory 1 (a ), would concern only known violators

of Section 58-84.1 of the Code o f Virginia, and such dis

closure would be made only to appropriate enforcement

authorities. Most certainly, this could not involve eco

nomic or other harm to the plaintiffs in error, or to any

law abiding member or contributor.

A R G U M E N T

L

Section 30-42(b) of the Code Clearly

Authorizes the Interrogatories

The movants assert that Interrogatory No. 1 (a ) is not

authorized by Section 30-42(b ) of the Code, first, be

cause neither the Fund, the Conference, nor the N.A.A.

C.P. support litigation “ contrary to” any law of Virginia.

9

As previously stated, this Court found in N.A.A..C.P. v.

Harrison, 202 Va. 142, 155-157, that each of the parties

was engaged in the unauthorized practice of law. The

unauthorized practice of law is plainly the “ promoting”

and “ supporting” of litigation contrary to the laws of

Virginia (see Section 54-44 of the Code of Virginia).

The movants next say that their contributors are not

“ supporting” litigation within the meaning of Section 30-

42(b). This position is untenable. As we have shown, the

plaintiffs in error publicly champion their interest and

participation in litigation to which they are not themselves

parties. It necessarily follows that any individual who

contributes funds to either of the movants for use in aid

of such purposes is “ supporting” litigation within the

terms of Section 30-42(b ) of the Code of Virginia.

All this falls clearly within the authority granted the

Committee by Section 30-42(b ).

II.

The Interrogatories Clearly State the Purpose of the

Committee’s Investigation and the Relevancy of the

Information Sought.

The movants next object to the interrogatories on the

asserted ground that their purpose has not been made

clear (F. 18, 19). We submit, however, that such purpose

and relevancy was plainly stated by the last paragraph of

the interrogatories themselves. As previously shown, that

paragraph says:

“ These interrogatories are propounded pursuant

to Section 30-42(b ) of the Code of Virginia, and

10

answers thereto are required to aid the Committee in

determining what donors, if any, have wrongfully

recorded their donations as allowable deductions in

their income tax returns filed with the Common

wealth of Virginia, and what recipients, if any, have

wrongfully failed to show as income in such returns

fees for legal services rendered in the Commonwealth

of Virginia.”

Moreover, an analysis of the detailed motion to quash

made by the N.A.A.C.P. and the Conference (R.

10) and the examination of Mr. Hobson by counsel for

the movants (R. 64-68, 111-113) demonstrates that the

movants knew exactly the purpose for which the names

were sought, and how they would be relevant to an in

quiry into the tax returns of contributors to, and lawyers

receiving fees from, the plaintiffs in error.

III.

Answering Interrogatory 1(a) Will Not Deny the M o

vants or Their Contributors Their Rights of “Freedom

of Association” or Rights of “Property.”

Our adversaries rely upon several cases recently decided

by the Supreme Court of the United States in support of

their contention that answers to Interrogatory 1(a) would

violate their rights o f freedom of association and rights

of property as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution o f the United States and by Sections

11 and 12 of the Constitution of Virginia.

The cases so relied on are:

1. N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 2 L. Ed. 2d

1488 (1958).

11

2. Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 4 L. Ed. 2d

480 (1960).

3. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479, 5 L. Ed. 2d 231

(1960).

4. Louisiana, ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366

U. S. 293, 6 L. Ed. 2d 301 (1961).

5. Gibson v. Florida Investigation Committee, 372 U.

S. 539, 9 L. Ed. 2d 929 (1963).

In each of these cases, there was an uncontroverted

showing that general public disclosure would be made,

and that harm could be expected to result from such

disclosure (cases 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 ) ; or that the informa

tion was not sought pursuant to a valid legislative purpose

(case 1 ); or that the information sought was broader

than reasonably necessary, or had no relevance, to the

legislative purpose (cases 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

By contrast, no public disclosure is here threatened, nor

will the giving of such answers cause economic or other

harm. Further, and as shown, the answering of Interrog

atory 1(a) will be narrow in scope and will serve a valid

legislative purpose.

The five cases just mentioned will be dealt with more

fully later in this brief, as will the “ violations of right”

asserted by the plaintiffs in error.

IV .

The Committee Seeks the Names of Contributors in

Keeping with a Valid Legislative Purpose

That the interests of an individual to “ freedom of asso

ciation” must give way to overbalancing public interests

is firmly established. It is where the State has failed to

12

show that information sought is relevant to a valid legis

lative purpose that disclosure has been denied.

As was said by Chief Justice Vinson in American Com

munications Associations v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382, 94 L.

Ed. 925, 944 (1950):

“ We have never held that such freedoms (freedom

of speech and association as guaranteed by First and

Fourteenth Amendments) are absolute. The reason

is plain. As Mr. Chief Justice Hughes put it, ‘Civil

liberties, as guaranteed by the Constitution, imply

the existence of an organized society maintaining

public order without which liberty would be lost in

the excesses of unrestrained abuses.’ * *

Similarly, in New York ex rel. Bryant v. Zimmernmn,

278 U. S. 63, 73 L. Ed. 184, 189 (1928), wherein it was

held that members of the Ku Klux Klan had no absolute

right to keep secret their membership, the Court said:

“The relators’ contention under the due process

clause is that the statute deprives him of liberty in

that it prevents him from exercising his right of

membership in the association. But his liberty in this

regard, like most other personal rights, must yield to

the rightful exertion of the police power. There can

be no doubt that under that power the state may pre

scribe and apply to associations having an oath bound

membership any reasonable regulation calculated to

confine their purposes and activities within limits

which are consistent with the rights of others and the

public welfare. * * *”

More recently, in Upliaus v. Wyman, 360 U. S. 72, 3 L.

Ed. 2d 1090 (1959), it was held that State interests in

13

investigating possible subversive activities outweighed an

individual’s right to “ freedoom of association.” In that

case there was compelled a disclosure to a New Hamp

shire legislative committee a guest list of a summer camp

used as a mecca by intellectuals whose views were said to

be “ unpopular” or “unorthodox.”

Of special significance is Communist Party v. S.A.C.

Board, 367 U. S. 1, 6 L. Ed. 625 (1961), wherein the

Court held that a federal statute requiring registration

and the filing of membership lists by the Communist

Party involved information sought for a valid legislative

purpose, and could not, therefore, be kept secret on

grounds of “ freedom of association.” The Court ex

plained its holdings in cases relied upon by movants as

being based upon findings that in those cases the infor

mation bore no relation to a valid legislative purpose (see

6 L. Ed. 2d at page 684 et seq.).

In contrast to the foregoing cases where disclosure

was compelled, the Supreme Court has denied the right

of the States to compel disclosure only where it has found

that such disclosure would result in harm, was not sought

in connection with a valid legislative purpose, or was “ too

broad” or without relevance to the purported purpose for

which disclosure was sought.

The case most strongly relied upon by movants is Gib

son v. Florida Investigation Committee, 372 U. S. 539,

9 L. Ed. 2d 929 (1963). There the N.A.A.C.P. was

being subjected to investigation, and the President of its

Miami Branch was called upon by the Committee to

testify at a public hearing from membership lists with

respect to the membership of certain persons alleged to

14

be subversives. The Court held that there was no rele

vance of the questions to the purpose of the investigation,

since there was no suggestion that the Miami Branch of

the N.A.A.C.P., or the national organization, were sub

versive, or that they were communist dominated or influ

enced. This again was an application of the principle that

the information sought must be relevant to the purpose

of the investigation. There, it was found that information

with respect to the membership lists had no relevance to

the subject under inquiry.

Similarly, in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449,

2 L. Ed. 2d 1488 (1958), the State’s Attorney General

sought the names o f N.A.A.C.P. members— “ in order to

determine whether petitioner [N.A.A.C.P.] was conduct

ing intrastate business in violation of the Alabama For

eign Corporation registration statute” (2 L. Ed. 2d at

page 1501). There the Court refused disclosure, because:

“ * * * Without intimating the slightest view upon

the merits of these issues, we are unable to perceive

that the disclosure of the names of petitioners rank

and file members has a substantial bearing on either

of them.” [i.e., the purposes for which the informa

tion was sought].

In Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 4 L. Ed. 2d

480 (1960), the Court struck down a clause in a muni

cipal licensing tax ordinance which required disclosure of

membership lists o f certain organizations. Recognizing

the purpose of the statute (i.e., taxation) to be valid, the

Court struck down the disclosure clause only because it

found that the names of members had no relation to the

taxes imposed. As the Court reasoned:

15

“ It was as an adjunct of their power to impose

occupational license taxes that the cities enacted the

legislation here in question. * * *

“ In this record we can find no relevant correlation

between the power of the municipalities to impose oc

cupational license taxes and the compulsory disclosure

and publication of the membership lists of the local

branches of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People. The occupational li

cense tax ordinances of the municipalities are square

ly aimed at reaching all the commercial, professional,

and business occupations within the communities.

The taxes are not, and as a matter of state law can

not be, based on earnings or income, but upon the

nature of the occupation or enterprise conducted.”

(4 L. Ed. 2d at pages 486-7)

Later, in Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479, 5 L.

Ed. 2d 231, 235-6 (1960), the Court explained its rea

sons for refusing to allow disclosure in the two last cited

cases, saying:

“ This controversy is thus not of a pattern with

such cases as National Asso. for Advancement of

Colored People v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 2 L. Ed.

2d 1488, 78 S. Ct. 1163, and Bates v. Little Rock,

361 U. S. 516, 4 L. Ed. 2d 480, 80 S. Ct. 412. In

those cases the Court held that there was no sub

stantially relevant correlation between the govern

ment interest asserted and the State’s effort to compel

disclosure of the membership lists involved. * * *”

The Court then held unconstitutional a statute of the

State of Arkansas which compelled every teacher, as a

condition of employment in a State-supported school or

college, to file annually an affidavit listing without limi

16

tation every organization to which he or she had belonged

or regularly contributed within the preceding five years.

Such annual listings were to be of public record.

The Court stated that the statute was so unlimited and

indiscriminate in its sweep that it unconstitutionally re

quired disclosure of associations which could have no rea

sonable relation to an individual’s qualifications as a teach

er. A response to Interrogatory 1(a) can carry with it no

disclosure of such unlimited, indiscriminate and irrelevant

proportions.

In Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366 U. S.

293, 6 L. Ed. 2d 301 (1961), also relied upon by movants,

the Court approved a temporary order restraining en

forcement o f a Louisiana general registration law requir

ing the N.A.A.C.P. to list, as matters of public record,

all its members with the Louisiana Secretary of State.

However, the Court did not determine the validity of the

statute. The Court said only: “ While hearings were held

before the temporary injunction issued, the case is in a

preliminary stage and we do not know what facts further

hearings before the injunction becomes final may dis

close.” (6 L. Ed. at 304)

It is important to recall that the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia, or any other government, has a vital interest in the

administration of its tax laws. As was early said by Chief

Justice Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat.

(17 U. S.) 316, 428, 4 L. Ed. 579, 607:

“ * * * It is admitted that the power of taxing the

people and their property is essential to the very ex

istence of government, and may be legitimately exer

17

cised on the objects to which it is applicable, to the

utmost extent to which the government may choose

to carry it * *

Similarly, in Bates v. Little Rock, supra, relied upon by

movants, the Court said at page 486 of 4 L. Ed. 2d:

“ It cannot be questioned that the governmental

purpose upon which the municipalities rely is a fun

damental one. No power is more basic to the ultimate

purpose and function of government than is the pow

er to tax. (Citing cases) Nor can it be doubted that

the proper and efficient exercise o f this essential gov

ernmental power may sometimes entail the possibility

of encroachment upon individual freedom.” (Citing

cases)

Moreover, governments have traditionally had unusual

power, as a matter of necessity, to inquire into private

matters where taxation is concerned. As was said in Hub

bard v. Mellon, 5 Fed. 2d 764, 766 (D. C. Cir. 1925), a

case cited with approval by the Supreme Court in Bates v.

Little Rock, supra:

“ . . . Congress had the power to provide for the levy

and collection of an income tax. It undoubtedly had

authority to compel natural persons and corporations

to make disclosures of matters of a distinctly private

character, so that each could be dealt with justly and

that the law might be properly enforced.”

Legislative investigation into the observance and adminis

tration of tax laws, such as the present Committee makes,

18

are likewise traditional. See, Gauge Lumber Co. v. Hen-

niford Co., 185 Wash. 180, 53 P. 2d 743 (1936), 103 A.

L. R. 513, and annotation following.

A comparison o f the cases above referred to in which

compelled disclosure has been upheld, with those wherein

disclosure has been refused, makes clear the consideration

upon which disclosure turns. As was stated by Mr. Jus

tice Harlan in Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479, 5 L. Ed.

2d 231, 243 (dissenting opinion) :

“ The legal framework in which the issue must be

judged is clear. The rights o f free speech and asso

ciation embodied in the ‘liberty’ assured against state

action by the Fourteenth Amendment (citing cases)

is not absolute, (citing cases) Where official action

is claimed to invade these rights, the controlling in

quiry is whether such action is justifiable on the basis

of a superior governmental interest to which such

individual rights must yield. When the action com

plained of pertains to the realm of investigation, our

inquiry has a double aspect: first, whether the inves

tigation relates to a legitimate governmental purpose;

second, whether, judged in the light of that purpose,

the questioned action has substantial relevance there

to. (citing cases)”

We submit that the case before this Court falls squarely

within the principle of those cases wherein compelled dis

closure has been approved. For the Committee has clearly

demonstrated that the information is sought in connection

with a legitimate governmental purpose, i.e., taxation.

Moreover, only a limited, and non-public, disclosure is

sought. And the relevancy of the information sought is

apparent and well understood by all concerned.

19

V.

Evidence Was Properly Excluded by the

Lower Court

Objections have been made to the lower court’s ruling

upon the admissibility o f certain evidence. First, the

plaintiffs in error assert that the lower court erred in

excluding an expression o f opinion of the Executive Sec

retary o f the Conference that legislation providing for

public disclosure of memberships had adversely affected

membership and fund raising campaigns of the movants

( F. 31). It being apparent from the record that any state

ment with respect to the effect o f certain unrelated laws

upon the amounts received by the movant organizations

would merely be a conclusion on the part of the witness

as to cause and effect, the lower court properly excluded,

as neither material nor competent, such statement of opin

ion. Whether the so-called “detrimental effect” upon fund

raising activities resulted from legislation was clearly a

matter o f speculation.

Secondly, the plaintiffs in error object to the lower

court’s having excluded hearsay testimony that persons

would suffer reprisals if identified publicly with the N.A.

A.C.P. or the Fund. Initially we say that disclosures to

the Committee are not divulged except where violations

o f the law appear. Further, the Fund’s own argument

betrays the weakness o f its point. As it says in its brief:

“ In excluding this evidence as irrelevant or as

hearsay, the court rejected the only means by which

the plaintiff in error could demonstrate the adverse

20

effect of disclosure of the information sought on both

the property rights o f the organization and the asso-

ciational rights o f its contributors.” (Emphasis ours)

(F . 32)

It will be recalled that the plaintiffs in error produced

as witnesses two o f their Virginia officials (one a dentist

of the City of Fredericksburg) and one official of national

prominence. Despite their public notoriety, none of these

witnesses could testify as to having personally suffered

any economic or other harm because o f their association

with the movants. Instead, they sought to testify only as

to what had been told them by others. Such testimony

was obviously hearsay and was properly excluded.

The movants further assert that there is one “ hearsay

rule” for ordinary cases and another for those cases where

constitutional principles are asserted (F. 32, 33). W e sub

mit that the law makes no such distinction.

In both N.A-.A.C.P. v. Alabama, supra, and Bates v.

Little Rock, supra, relied upon by the Fund as establish

ing this anomalous proposition, there was direct evidence

that public identification with the movants had resulted

in reprisals.

Finally, the movants object to the trial court’s refusal

to admit in evidence their tendered Exhibits A and B

(N. 26, 27, F. 41). Exhibit A was the report o f a com

mittee created by Chapter 34 o f the Acts o f Assembly of

1956, Extra Session, which committee had the same name

as the defendant in error. That committee ceased to exist

by the terms of its authorizing statute upon the convening

of the 1958 session o f the General Assembly. Exhibit B was

the report of the Committee on Law Reform and Racial

Activities created by Chapter 37 o f the Acts o f Assembly,

21

1956 Extra Session. That committee was abolished by

Chapter 373 of the Acts o f Assembly, 1958. Thus, neither

o f the committees whose reports were offered as exhibits

existed at the time o f the trial in this case. Moreover their

reports did not relate in any respect to the activities o f the

present Committee. Clearly, they were not relevant under

any theory of the case.

There is another, and compelling, reason why these

exhibits were properly refused. Each of the documents

was offered in an effort to show that the motives o f the

Committee in issuing the present interrogatories were

improper (N . 27, F. 42). As we show elsewhere in this

brief, no inquiry into the motives of the General Assem

bly in creating the Committee, or o f the Committee in

making its investigations, may judicially be made.

V I.

No Inquiry May Be Made Into Motives Prompting the

Committee’s Creation, Nor Motives Prompting Its

Investigation.

The Fund devotes nine pages (F. 33-41), and the N.A.

A.C.P. six pages (N . 20-25), to an attack upon the mo

tives of the Committee and of the General Assembly in

creating it. That such motives are not a proper subject

for judicial inquiry, and cannot be used as a basis for

attack, either upon a committee’s action or the statute cre

ating it, is a principle long settled.

This Court has often held that the motives of the Gen

eral Assembly are not relevant in determining the consti

tutionality of a statute. See Shenandoah Lime Company

v. Governor, 115 Va. 865,80S. E. 753 (1914); Telephone

22

Company v. Nezuport News, 196 Va. 627, 85 S. E. 2d

345 (1955); N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee, 199 Va. 665, 678,

101 S. E. 2d 631 (1958). The same doctrine was long

ago recognized, and has been consistently followed, by

the Supreme Court o f the United States. In Fletcher v.

Peck, 6 Cranch. 87, 131, 3 L. Ed. 162, 176 (1809), an

act o f the Georgia legislature was attacked on the ground

that it had been secured by wholesale bribery. Chief Jus

tice Marshall, expressing the Court’s decision that it

should not inquire into the motives of the legislature,

said:

“ . . . If the title be plainly deduced from a legisla

tive act, which the legislature might constitutionally

pass, if the act be clothed with all the requisite forms

o f a law, a court, sitting as a court o f law, cannot sus

tain a suit brought by one individual against another

founded on the allegation that the act is a nullity, in

consequence o f the impure motives which influenced

certain members o f the legislature which passed the

law.”

Later, in Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries and W . Co.,

251 U. S. 146, 161, 64 L. Ed. 194, 202 (1919), Mr. Jus

tice Brandeis said:

“ No principle o f our constitutional law is more

firmly established than that this court may not, in

passing upon the validity of a statute, inquire into the

motives of Congress (citing cases). Nor may the

court inquire into the wisdom of the legislation (cit

ing cases). Nor may it pass upon the necessity for

the exercise o f a power possessed, since the possible

abuse o f a power is not an argument against its exist

ence.”

23

Equally well established is the principle that a court

may not inquire into the motives o f a committee or its

individual members in a court test o f the validity o f their

actions. In Tenney v. Brand hove, 341 U. S. 367, 377, 95 L.

Ed. 1019, 1027 (1951), Brandhove brought an action

against a California legislative committee engaged in

investigation o f communist activities. He alleged that

an investigative session, at which he testified, was de

signed to intimidate, silence and deter him from the exer

cise o f the his rights of “ freedom of speech.” Rejecting

this contention, the Court said:

<<* * * The holding 0f fhis Court in Fletcher v.

Peck * * * that it was not consonant with our scheme

of government for a court to inquire into the motives

o f legislators, has remained unquestioned. * * *

“ Investigations, whether by standing or special

committees, are an established part of representa

tive government. Legislative committees have been

charged with losing sight of their duty of disinter

estedness. In times of political passion, dishonest or

vindictive motives are readily attributed to legislative

conduct and as readily believed. Courts are not the

place for such controversies. Self-discipline and the

voters must be the ultimate reliance for discouraging

or correcting such abuses.”

See to the same effect, Watkins v. United States, 354 U.

S. 178, 1 L. Ed. 2d 1273, 1291 (1957); Goesaert v.

Cleary, 335 U. S. 464, 466, 93 L. Ed. 163, 166 (1948);

and Daniel v. Family Security Life Insurance Company,

336 U. S. 220, 224, 93 L. Ed. 632, 636 (1949).

24

V II.

Other Matters Advanced by the Plaintiffs in Error

The plaintiffs in error advance so many diverse theories

in an effort to thwart the Committee’s Interrogatories

that to respond to each at length would require a brief

o f unjustifiable length. However, we will here reply as

briefly and concisely as we may to each o f those theories.

(a)

Equal Protection

The Fund asserts that Section 30-42(b ) was enacted

to single out the plaintiffs in error for special investiga

tion. Such is not the case.

Section 30-42(b ) directs investigation with respect to

all who promote or support litigation to which they are

not parties. Known to be included within this category

are labor unions, trade associations, groups such as the

American Civil Liberties Union, and others.

Moreover, movants’ own exhibit (Exhibit C, pages 8

and 9) shows that this Committee has investigated other

groups having no connection with either the movants or

the colored race. And this Court has previously found

that the Committee has investigated, not only the N.A.A.

C.P. and its affiliates, but other “unrelated persons and

organizations.” See, N.A.A.C.P. v. Committee, 201 Va.

890, 894, 114 S. E. 2d 721 (1960).

(b )

Constitutionality of Section 58-84.1

The Fund now asserts that Section 58-84.1, denying

tax deductibility of contributions to groups supporting

litigation, is unconstitutional. No such argument was

25

made in the lower court, nor was error so assigned on

this appeal. Thus, the issue may not now be raised. Rules

o f Court 5:1, Section 4.

Despite this, we point out that their argument is clearly

frivolous. If denial of a tax deduction for contributions

to any organization which operates within areas o f “ free

speech” is invalid, as they assert, then the long established

denial, under both Federal and State law, of such deduc

tions for contributions to groups disseminating propa

ganda would likewise be unconstitutional (see Section 58-

81 (m ) (2 ) of the Code of Virginia). It is plain that Sec

tion 58-84.1 is merely a legislative recognition of the fact

that groups so supporting litigation are not “ charitable”

in nature, as is contemplated by Section 58-81 (m ) (2 ).

(c)

T he A ttorney General’s Representations

in Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P.

In Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. Ed. 2d

1152 (1959), the Attorney General of Virginia represent

ed to the Supreme Court o f the United States that he

would not enforce Chapters 31, 32, 33 or 36 of the Acts

o f Assembly, 1956 Extra Session, until they had been

construed by the courts of Virginia. This representation,

says the Fund (F. 47), precludes the Committee from

pursuing its investigations under Chapter 373 o f the Acts

of Assembly o f 1958. It is obvious that the Attorney

General, an officer of an executive branch of government,

could not and would not make representations purporting

to bind a legislative body. Aside from this, a comparison

o f the statute authorizing the Committee’s investigation

with those statutes involved in N.A.A.C.P. v. Harrison,

26

supra, makes clear that no representations affecting this

Committee were intended; and this so because the Com

mittee is directed to investigate with respect to all laws

relating to the administration of justice, including the

common law. Suspending the enforcement or considera

tion of those laws could hardly have been contemplated.

C O N C LU SIO N

As earlier mentioned, the Fund has answered Interrog

atories 1 (b ), 2 (a ) and 2 (b ), and is contesting only its

duty to answer Interrogatory 1 (a ). The N.A.A.C.P. and

the Conference, on the other hand, have filed no answers

whatever.

It is plain that Interrogatories 1 (b ), 2 (a ) and 2 (b )

(and we think also 1 (a ) ) inquire into the activities o f the

plaintiffs in error in Virginia. The N.A.A.C.P. has earlier

conceded its obligation to inform of its activities in any

given State. Thus, in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S.

449, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1488, 1500 (1958), the N.A.A.C.P. ad

mitted that they were entitled to no special immunity

respecting their activities within a State, and that they

had no right to disregard a State’s laws. This concession

was approved by the Supreme Court o f the United States

when it said:

“ It is important to bear in mind that petitioner

[N A A C P] asserts no right to absolute immunity

from state investigation, and no right to disregard

Alabama’s laws. As shown by its substantial com

pliance with the production order, petitioner does not

deny Alabama’s right to obtain from it such infor

mation as the State desires concerning the pur

poses o f the Association and its activities within the

State.” (Emphasis ours)

27

In this proceeding, the plaintiffs in error (most par

ticularly the N.A.A.C.P. and the Conference) take the

position that the Commonwealth of Virginia has no right

to inquire into either their own or their contributors’ fiscal

affairs. Having taken the position before the Supreme

Court in the Alabama case that a State had a right “ to

obtain from it (N .A .A .C .P.) such information as the

State may desire concerning * * * its activities within

the State,” they may not now take the inconsistent posi

tion that a duly created Committee of the General Assem

bly o f Virginia has no such right. See, Burch v. Grace

Street Bldg. Corp., 168 Va. 329, 340, 191 S. E. 672

(1937).

We submit that the decision of the Hustings Court of

the City of Richmond was plainly right and should be

affirmed.

W e certify that copies of this brief were duly mailed

to all other counsel of record on the day on which the

originals were filed with the Clerk o f this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Committee on Offenses A gainst

T he A dministration of Justice

Hon. Robert Y. Button

Attorney General o f Virginia

Supreme Court of Appeals Building

Richmond, Virginia

W illiam H. K ing

915 Mutual Building

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel for Defendant in Error

June 12,1963

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R 1 N T I N O C O M P A N Y • R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N I A