Coralluzzo v. New York Parole Board Judgment

Public Court Documents

August 5, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coralluzzo v. New York Parole Board Judgment, 1977. 1c70986c-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7968e6e9-04e9-403f-87c9-03aa35e554c0/coralluzzo-v-new-york-parole-board-judgment. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

^ e v -

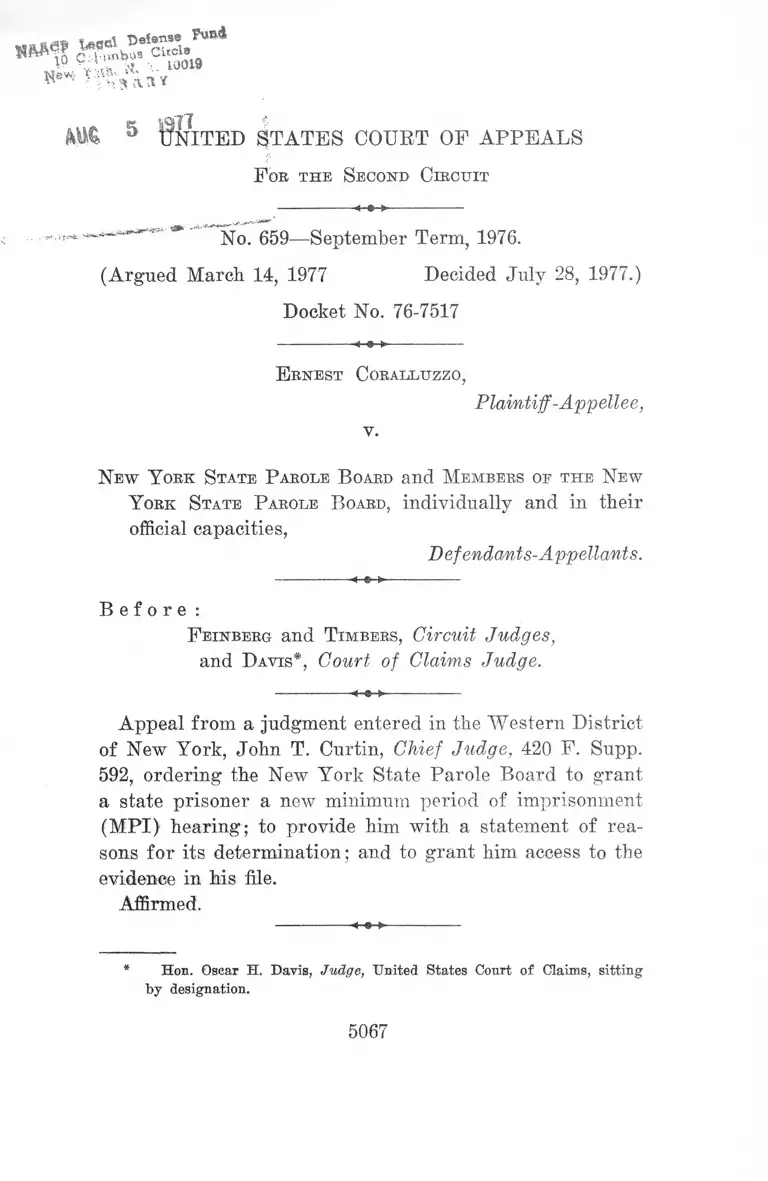

Mte 5 Un i t e d s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

P oe the Second Circuit

' No. 659—September Term, 1976.

(Argued March 14, 1977 Decided July 28, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-7517

E rnest Coralluzzo.

Plaintiff-Appellee,

V.

New Y ork State P arole B oard and Members oe the New

Y ork State Parole B oard, individually and in their

official capacities,

Appeal from a judgment entered in the Western District

of New York, John T. Curtin, Chief Judge, 420 P. Supp.

592, ordering the New York State Parole Board to grant

a state prisoner a new minimum period of imprisonment

(M PI) hearing; to provide him with a statement of rea

sons for its determination; and to grant him access to the

evidence in his file.

Affirmed.

Hon. Oscar H. Davis, Judge, United States Court o f Claims, sitting

by designation.

Defendants-Appellants.

B e f o r e :

F einberg and T imbers, Circuit Judges,

and Davis*, Court of Claims Judge.

5067

M a r k C. R u t z i c k , Deputy Asst. Atty. Gen., New

York, N.Y. (Louis J. Lefkowitz, Atty. Gen.

of the State of New York, Samuel A. Hir-

showitz, First Asst. Atty. Gen., and Kevin

J. McKay, Deputy Asst. Atty. Gen., New

York, N.Y., of counsel), for Defendants-

Appellants.

P h i l i p B. A b r a m o w i t z , Buffalo, N.Y. (Robert C.

Macek, Buffalo, N.Y., of counsel), for Plain

tiff-Appellee.

T i m b e r s , Circuit Judge:

This appeal by the New York State Parole Board and

its members from an order entered in the Western District

of New York, John T. Curtin, Chief Judge, 420 F. Supp.

592, in a civil rights action by a state prisoner, presents for

review under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment another procedural aspect of the New York

State parole system.

The procedure in question is the minimum period of im

prisonment (MPI) hearing conducted pursuant to N.Y.

Correction Law §212(2) (McKinney Supp. 1976).1 We hold

that the New York MPI procedure is subject to the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; that the

New York State Parole Board must provide a statement of

1 We previously have held subject to the due process clause New York’s

parole release procedure, see United States ex rel. Johnson v. Chairman,

New York State Board of Parole, 500 F.2d 925 (2 Cir.), vacated as

moot, 419 TT.S. 1015 (1974), and its procedure for conditional release o f

prisoners serving sentences o f less than one year. See Zuralc v. Began,

550 F.2d 86 (2 Cir.), cert, denied,------ - TJ.S. ------- (1977), 45 TJ.S.L.W.

3841 (U.S. June 27, 1977). We also have clarified the requirements of

the due process clause as applied to New York’s parole revocation proce

dure. See United States ex rel. Carson v. Taylor, 540 F.2d 1156 (2 Cir.

1976).

5068

reasons when it determines a MPI which exceeds the

statutory minimum; and that under the particular circum

stances of this case the prisoner must be granted access to

the evidence in his file. We affirm.

I.

For those prisoners subject to it, the MPI hearing is the

threshold stage of the parole release process. Depending

on the individual case, it results either in immediate release

or in the scheduling of consideration for parole at some

fixed date in the future. Specifically, when there has been

imposed on a prisoner an indeterminate sentence but no

minimum term, N.Y. Correction Law §212(2) requires the

New York State Parole Board to meet with him and review

his file between nine and twelve months from the date he

commenced Ms sentence. The Board then must “make a

determination as to the minimum period of imprisonment

to be served prior to parole consideration.” Under the stat

ute, in the case of a prisoner sentenced to an indeterminate

term with no minimum, the Board may provide for a min

imum period of incarceration as short as one year. Should

it decide to set a longer minimum period, it subsequently

may reduce the period initially fixed.

A MPI hearing was held in the instant case pursuant to

the statutory directive. On February 28, 1975, upon a plea

of guilty in the Supreme Court, Bronx County, to one count

of criminal sale of a dangerous drug in the second degree

in violation of N.Y. Penal Law §220.35 (McKinney 1967),

Ernest Coralluzzo was committed to the New York State

Department of Corrections to serve an indeterminate sen

tence not to exceed fifteen years. N.Y. Penal Law §70.00(1)

(McKinney 1975). On January 15, 1976, he met with three

members of the Parole Board at a MPI hearing. He re

quested release upon the expiration of the one year statu-

5069

tory minimum. After the hearing he received a form notice

from the Board informing him that his MPI had been set at

five years and that he would appear before the Parole

Board in February 1980 for release consideration. No rea

sons for the decision were stated on the form notice. On

March 3, 1976, twelve days after Coralluzzo commenced

the instant action, the Board sent him a second notice which

stated the following reasons for its decision:

“ The case history makes it reasonable to conclude that

this man’s involvement in narcotics traffic is deep-

rooted and high level. Permanent separation from

drugs seems improbable for five years.”

Coralluzzo contends that his involvement in the narcotics

traffic was far from “deep-rooted and high level” , and that

the Board extrapolated this from erroneous statements in

his prison file which asserted that he was involved with

organized crime. We cannot say that this contention is al

together speculative. Coralluzzo obtained from the state

court at the time he was sentenced an order striking from

his probation report an unsupported reference to his con

nections with certain families of organized crime.

On February 20, 1976, Coralluzzo commenced the instant

civil rights action pursuant to 42 TJ.S.C. §1983 (1970). He

sought a declaratory judgment that the MPI procedure had

violated his due process rights and an order directing the

Board to reconsider his application for release in a man

ner consonant with due process requirements, tie con

tended, inter alia, that the Board improperly had failed to

inform him of the reasons for its decision and the evidence

upon which it had relied, and that the Board should have

given him an opportunity to examine the evidence in his

file. In an opinion filed August 6, 1976, as amended Octo

ber 6, 1976, Chief Judge Curtin held that the Board’s post

5070

facto statement of reasons was an insufficient remedy for

its initial due process violation; he ordered the Board

to grant a new MPI hearing to he followed with a state

ment of reasons; and he ordered the Board to “ disclose

to the plaintiff all of the evidence, in unabridged form,

which may be considered against him, absent a showing

of good cause for keeping the information secret.” 420 F.

Supp. 592, 596. From that order, the Board and its mem

bers have appealed.

II.

In view of the claims of the parties and the decision of

the district court, we are presented with the threshold

question whether the prisoner has an interest at stake in

the MPI determination sufficient to warrant due process

protection. We hold that he does. This holding follows as

a sequel to our decision in United States ex rel. Johnson v.

Chairman, New York State Board of Parole, 500 F.2d 925

(2 Cir.), vacated as moot, 419 TJ.S. 1015 (1974). There, in

light of the Supreme Court’s decision applying the due

process clause to parole revocation proceedings, Morrissey

v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972), we held that prospective

parole entails a liberty interest commanding due process

recognition. We stated, “Whether the immediate issue be

release or revocation, the stakes are the same: conditional

freedom versus incarceration.” 500 F.2d at 928. See

Zurak v. Regan, 550 F.2d 86 (2 Cir.), cert, denied,------ U.S.

------ (1977), 45 U.S.L.W. 3841 (U.S. June 27, 1977); cf.

Williams v. Ward, ------ F.2d —— , — — (2d Cir. 1977),

slip op. 3829, 3859-61 (May 27, 1977). The same interest

in conditional freedom is at stake at a MPI hearing. As

we said in Walker v. Oswald, 449 F.2d 481 (2 Cir. 1971),

the MPI proceeding is “ an integral part of the parole re-

5071

lease process.” 2 Moreover the statutory scheme holds out

the possibility of immediate release at the MPI stage. At

least with respect to the preliminary question of the ap

plicability of due process, the MPI and parole release de

terminations are distinguishable in immaterial degree only,

not in kind.

The Board contends that the MPI proceeding is ma

terially different from the various parole release situations

dealt with in our prior decisions because the prisoner,

having no reason to expect “ imminent liberty” , presents

only a “very tenuous” liberty interest. To be sure, the

principal purpose of the §212(2) procedure is to facilitate

the scheduling of a later parole release hearing and as an

incident of that to establish a minimum period of im

prisonment. Depending on the individual case that mini

mum period may exceed one year. But we find no indica

tion either in Johnson or in the Supreme Court’s recent

decisions dealing with liberty interests of prisoners, see

Meachum v. Fano, 427 U.S. 215, 224-25 (1976); Wolff v.

McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 555-58 (1974); Morrissey v.

Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 480-82 (1972), that a substantial pos

sibility of immediate release is the sine qua non of a cog

nizable liberty interest. To draw the constitutional line

where the statistics show it to be more likely than not that

the particular proceeding will result in immediate release

could risk insulating from due process protection those

stages of the parole release process which as a practical

matter most seriously affect a prisoner’s liberty interest.

The MPI hearing strikes us as involving precisely this

type of liberty interest. It results in an effective minimum

period of imprisonment. The statute provides the prisoner

with no practical method of obtaining reconsideration by

2 In WaXker, we equated parole release and M PI hearings for the pur

pose of holding that no right to counsel attaches at a M PI hearing.

5072

the Board until the date it has set for the parole release

hearing arrives. The MPI hearing therefore may be the

crucial component in the series of judicial and administra

tive decisions which combine to determine how long the

prisoner remains incarcerated.

In view of these considerations, as -well as the statutory

possibility of immediate release, we hold that the MPI

hearing affects a prisoner’s liberty interest sufficient to

warrant due process protection.3

III.

We turn next to the two questions here presented re

garding MPI hearing due process requirements: (1)

whether the prisoner must be given a statement of the rea

sons for the Board’s decision, including the essential facts

upon which the Board’s inferences are based; and (2)

whether the prisoner must be given access to the evidence

in his file.

(A) Statement of Reasons

The district court correctly required the Board to fur

nish a statement of reasons and facts, 420 F. Supp. at 596,

in compliance with the standards we enunciated in John

son, supra, 500 F.2d at 934. Here, as in a parole release

determination, the inmate has a strong interest in the pro

ceeding and the burden on the Board is comparatively in

significant. As we recently reemphasized in Zurab, supra,

550 F.2d at 95, “ a requirement of a statement of reasons

and facts is necessary to protect against arbitrary and

capricious decisions or actions grounded upon impermis-

3 In so holding we reiterate the ruling o f the state court in Festus v.

Megan, 50 App. Div. 2d 1084, 376 N.Y.S.2d 56 (4th Dept. 1975) (mem.).

5073

sible or erroneous considerations.” See also Haymes v.

Regan, 525 F.2d 540, 544 (2 Cir. 1975).

The district court also correctly declined to accept the

Board’s related statement of reasons, 420 F. Supp. at 595-

96, as an effective cure for the constitutional deprivation

committed by its initial act of summarily imposing a five

year minimum period of incarceration. Johnson stressed

that requiring a statement of reasons promotes thought on

the decider’s part and compels him to cover the relevant

points and to eschew irrelevancies. 500 F.2d at 931. The

belated statement here, a verbatim repetition of an internal

communication made by the Board at the time of its

initial decision, does not comply with the standard of

thorough consideration suggested in Johnson.

The statement furnished here would have been inade

quate even if it had not been belated. True, it did set forth

the grounds of the Board’s decision—that Coralluzzo was

involved heavily in drug traffic. But applying here the

standards we formulated in Johnson, supra, 500 F.2d at

934, and Haymes, supra, 525 F.2d at 544, we hold that the

Board was required to take the further step of stating the

essential facts upon which it relied in reaching its decision.

It is impossible to determine from the statement furnished

by the Board whether it relied upon independent evidence

of Coralluzzo’s connections with organized crime or upon

activities on the part of Coralluzzo aside from such a con

nections.4

4 This omission is particularly significant under the circumstances of

this case. Coralluzzo obtained from the state court an order striking from

his probation report an unsupported reference to his connections with

organized crime. Any reliance by the Parole Board on this information

in setting his M PI plainly was improper. Vet on the basis o f the state

ment o f reasons given a reviewing court would not be in a position to

determine whether the Board had relied on such information.

5074

(B) Access To Evidence In File

Applying the three-pronged test formulated by us in

Haymes, supra, 525 F.2d at 543, the district court held that

the Board must disclose to the prisoner the actual evidence

in his file at all MPI hearings. 420 F. Supp. at 595 n.3,

596-99.

In so holding the district court did not have the benefit

of our subsequent decision in Holup v. Gates, 544 F.2d 82

(2 Cir. 1976), cert, d en ied ,------TJ.S. -------- - (1977), 45

U.S.L.W. 3634 (U.S. March 21, 1977). There the prisoner

claimed that “ as a matter of constitutional law, any parole

procedure which fails to allow every prospective parolee

an inspection of his file in advance of that hearing . . . is

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. . . .” 544 F.2d

at 85. Under our Haymes test resolution of that claim re

quired a comparative assessment of the prisoner’s need to

see the materials and the burden on the State of examining

and redacting the file of each prisoner. But the record in

Holup lacked the facts necessary for that assessment.

There was no showing of the extent to which the State’s

files were inaccurate or of the extent of materiality of any

inaccuracies to the parole decision. As a result it was

doubtful whether the disclosure demanded would be of any

real use to the prisoners, 50% of whom received parole

upon their first hearing in any event. Nor was it clear as

to what administrative burden disclosure would place upon

the State. Accordingly, since the record lacked “ sufficient

hard evidence” to permit application of the due process

balancing test, we remanded for further proceedings. 544

F.2d at 87.

I f we were disposed to formulate a general rule regard

ing a prisoner’s access to evidence in his file in connection

with MPI hearings, the record in the instant case would be

no more suitable than that in Holup. Although Coralluzzo’s

5075

claim of a factual error in his own file might be probative,

544 F.2d at 86, it is an unsatisfactory substitute for a

showing of the frequency and gravity of the State’s past

errors. As for the State’s interest, the instant record is

barren of any hard facts regarding the burdens of under

taking disclosure and of redacting sensitive information.

With respect to the particular plaintiff, Coralluzzo, how

ever, this case is distinguishable from Iiolup. There, by the

time the case reached us only one of a number of initial

plaintiffs remained to present a justiciable controversy and

that plaintiff had not had a parole hearing. In the mooted

eases, parole decisions had been made after notice had been

given of the evidence upon which the parole board intended

to rely and there were no claims of prejudice from any al

leged lack of disclosure. Here, by contrast, Coralluzzo as

serts a substantial claim that the Board relied upon er

roneous information which had been stricken from Ms

probation report by a state court order.

Due process is flexible and calls for such procedural pro

tections as the particular situation demands, see, e.g.,

Morrissey v. Brewer, supra, 408 TJ.S. at 481; it often is

“ sensitive to what proves necessary in practice to a fair

procedure. . . .” (emphasis in original) Williams v. Ward,

- — F .2d------, ------- (2 Cir. 1977), slip op. 3829. 3863 (May

27, 1977). Pursuant to this principle, we suggested in

Williams that “there may . . . be circumstances where an

inmate plausibly contends that the only way he can demon

strate reliance on an impermissible factor or can show a

particular allegation concerning his record to be false . . .

is by obtaining access to the detailed evidence in Ms file,

albeit in a redacted form.” ------ F,2d a t ------ , slip op. at

3864-65. We were not confronted with that situation in

Williams because the prisoner there had not “ suffered any

prejudice from the lack of access to his files.” Id. at 3865.

5076

He had known prior to his parole release hearing that his

file contained the information which he later alleged to he

false hut had taken no steps to rebut at the hearing before

the Board the facts in the file. Moreover, the Board in

cluded in its statement of reasons two substantial inde

pendent grounds for its decision. Id. at 3865-66.

This is an entirely different case. Ooralluzzo has taken

the initiative to purge his file of the information which he

contends is false. The Board’s statement of reasons per

mits the inference that the state court’s order to strike the

reference to organized crime in the probation report was

disregarded. As a result, Ooralluzzo presents a substantial

factual contention regarding the basis for the Board’s de

cision. Since disclosure of the file’s contents is the only way

this issue can be resolved, see Williams, supra, slip op. at

3864-65, Coralluzzo’s interest in disclosure is substantial

enough to remove him from the undifferentiated class of

prisoners subject to the MPI process and to grant him ac

cess to his file. Moreover, there will be no prejudice to the

state in accommodating Ooralluzzo. He apparently already

has seen much of the material in his file. The Board, if

necessary, can withhold material under the “good cause”

exception in the district court’s order. 420 F. Supp. at 596,

599.

We emphasize the narrow scope of our holding that the

State must grant this prisoner access to Ms file. In applv-

ing the exception suggested in Williams to the peculiar

facts of this case, we note that those facts have come to

light only because the State, in however defective a man

ner, already has conducted a MPI proceeding. We join

with Judge Friendly in Williams in “not wishfing] to

prejudge the issues left for examination in the Holup re

mand. . . .” ------F.2d a t ------- , slip op. at 3864.

Affirmed.

5077

480— 8-1-77 . USCA— 4221

ME11EN PRESS INC, 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177

219