Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. c79290c8-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79750ecd-0378-4fbb-8fbd-a423e5cc6e70/kelley-v-metropolitan-county-board-of-education-of-nashville-and-davidson-county-tn-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

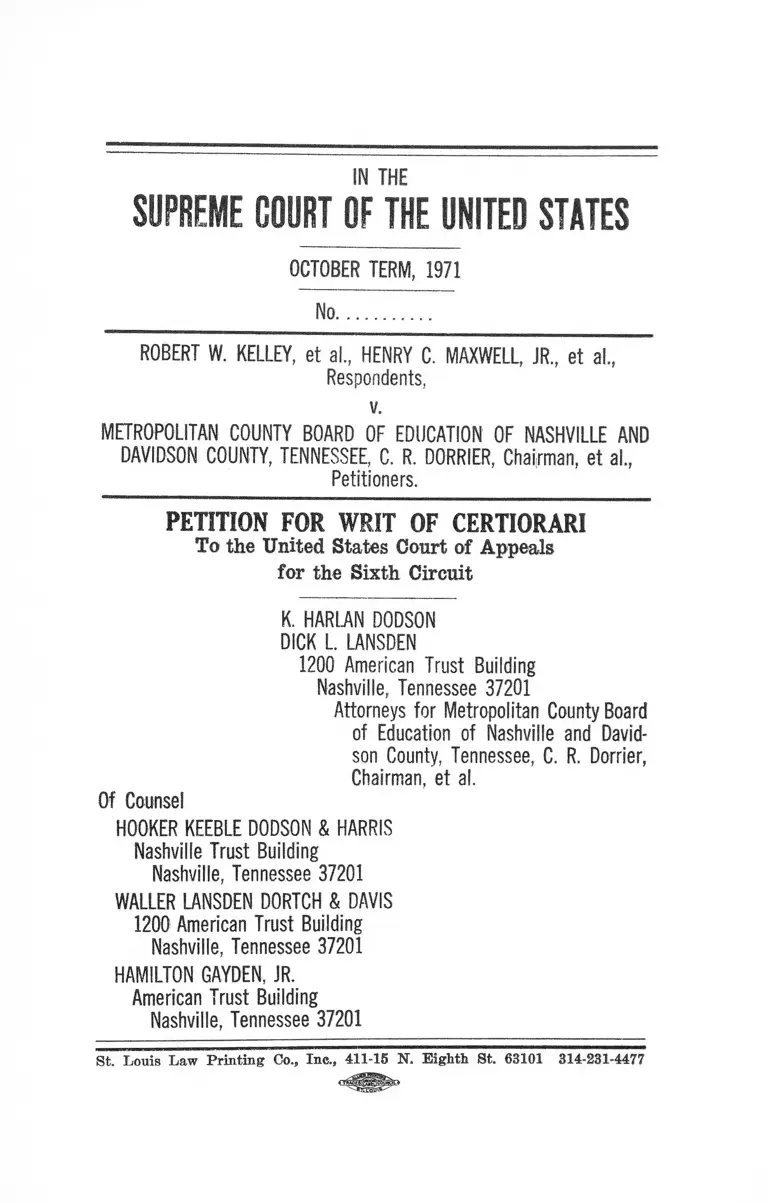

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No.............................

ROBERT W. K ELLEY, et al., HENRY C, MAXW ELL, JR ., et al.,

Respondents,

v.

METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF NASHVILLE AND

DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, C. R. DORRIER, Chairman, et al.,

Petitioners.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

K. HARLAN DODSON

DICK L. LANSDEN

1200 American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Attorneys for Metropolitan County Board

of Education of Nashville and David

son County, Tennessee, C. R. Dorrier,

Chairman, et al.

Of Counsel

HOOKER KEEBLE DODSON & HARRIS

Nashville Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

W ALLER LANSDEN DORTCH & DAVIS

1200 American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

HAMILTON GAYDEN, JR.

American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

St. Louis Law Printing Co., Inc., 411-15 N. Eighth St. 63101 314-231-4477

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions Below ............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 2

Questions Presented...................................................... 2

Statutes Involved................. 3

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Involved................ 3

Statement .................................................................. 3

Argument, Question 1 .................................................. 5

Argument, Question 2 .................................................. 7

Argument, Question 3 .................................................. 8

Conclusion .............................................................. 10

Appendix “ A”—Opinion of the District C ourt......... A-l

Appendix “ B ”—Opinion of the Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit ...................................................... A-25

Appendix “G”—Order of the Court of Appeals Deny

ing Stay .....................................................................A-66

Appendix “ D”—Report of Director of Metropolitan

Public Schools ............................................................ A-67

Table of Cases

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 ............................................ 2,5,6,7,10

Winston-Salem, etc. v. Catherine Scott et al., No. 71-

274, Oct. Term, 1971 ................................................ 6,7

Miscellaneous

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23—Class

Actions ....................................................................3, 8,9

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United S ta tes............................................................. 3

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No.

ROBERT W. K ELLEY, et al„ HENRY C. MAXWELL, JR., et a!.,

Respondents,

v.

METROPOLITAN COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF NASHVILLE AND

DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, C. R. DORRIER, Chapman, et al.,

Petitioners.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

To the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit:

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is not yet officially

reported, but is set out in its entirety as Appendix “B” to

this petition at pages A-25-A-6'5. The opinion of the Dis

trict Court likewise has not yet been officially reported in

sofar as we can ascertain, but is set out as Appendix “ A”

at pages A-l-A-24.

JURISDICTION

The opinion and order of the United States Court, of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit was entered on May 30, 1972.

A petition for stay pending the filing of a petition for cer

tiorari to this Honorable Court was denied by the Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit on July 25, 1972 (Appendix

“ C” , p. A-66).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. The District Court made no finding that assignment

of children to the school nearest their home would not ef

fectively dismantle the city’s dual school system to the ex

tent that it was state-imposed. Nevertheless, the District

Court ordered cross-town busing with some bus rides as

long as three hours, necessitating staggered openings of

schools (from 7 A. M. to 10 A. M.) and staggered closings

(from 1:30 P. M. to 4:30 P. M.), with the result that in

winter months young children walked to pick-up points be

fore daylight, and walked home after dark, along streets

sometimes unlighted and sometimes without sidewalks.

Did the Court of Appeals err in affirming the judgment

despite the absence of any finding by the District Court

that such busing was necessary to eliminate state imposed

segregation1?1

2. The District Court approved a plan for the desegrega

tion of schools which fixed a definite percentage of racial

mix for each school and directed no deviation therefrom

which would lessen the degree of fixed racial mix. Was

the Court of Appeals in error in affirming the District

Court on the theory that Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U. S. 1, permitted (required) such

as a matter of substantive constitutional law?

— 2 —

1 This obviously creates situations where working mothers with

three or more school children are forced to leave for work before

the children leave for school and children can be unattended for

as much as two and a half hours before school,

3. Without compliance with Rule 23 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, the District Court entered a judgment

requiring the busing of children of a class of which none

of the plaintiffs was a member. Did failure of the parties

to invoke Rule 23 prior to judgment constitute a waiver

which relieved the Court of its duty of compliance and

thereby validated the judgment!

STATUTES INVOLVED

This petition for certiorari involves no statute, but

involves Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case originated in 1955 when suit was instituted

by Robert W. Kelley et al., seeking desegregation of the

Nashville school system only. In 1960 the Henry C. Max

well, Jr., et al., case was filed and it sought desegregation

of the Davidson County schools. Subsequently, the gov

ernments of the City of Nashville and of Davidson County

were consolidated, and in September, 1963, the two cases

were likewise consolidated. Prior to September, 1963, the

Court had approved plans for the desegregation of each

of the two school systems which were substantially iden

tical. After the consolidation of the governments of

Nashville and Davidson County there was only one school

board and it was known as the Metropolitan County Board

of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, Ten

nessee, which is the petitioner here.

Following petitions in the consolidated desegregation

cases based upon the insistence that the school system

was not complying with new concepts for desegregation

as announced by this Honorable Court, and hearings be

fore the then district judge, the Honorable William E.

Miller, the petitioning school board submitted plans and

hearings were had before Judge Miller and his successor,

Judge L. Clure Morton, which began in March of 1971,

and continued, though not continuously, through June 9,

1971. The hearing before Judge Morton was predicated

upon pleadings filed by some of the original plaintiffs and

some additional plaintiffs, and alleged that the original

plaintiffs had either graduated or were enrolled in schools

which were desegregated, and sought leave for additional

students of Cameron High School to intervene and be

come plaintiffs, which was allowed. The only named

plaintiff or intervening plaintiff remaining in school at

the time of the hearing and at the time of the decision

in the District Court was a student in senior high school.

At the hearing the Court rejected the plan submitted

by the school board and the plan submitted by plaintiffs.

The Court requested the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare to submit a plan and adopted the plan sub

mitted with minor variations. Basically, the plan con

templated cross-town busing of black students to formerly

white schools in grades one through six and the trans

portation of white students to formerly all black or pre

dominantly black schools in the other grades so that the

nonelementary grades would occupy the space vacated by

the elementary grades during the school day. As a part

of the plan the District Judge adopted the charts appear

ing at pages A-21 through A-24 of Appendix ‘‘A” , which

charts fixed a definite percentage of racial mix for each

school, and the District Court in its opinion, at page A-ll

of Appendix “ A” , authorized the board of education to

make minor alterations in the boundaries, provided such

alterations did not lessen the degree of segregation in the

plan.

After the plan adopted by the District Court was im

plemented, the director of schools filed a report attached

as Appendix “ D” to this petition, which report reflects

the hardships encountered in the execution of the plan.

— 4 —

5

ARGUMENT

Question 1

This Court has previously pointed out in its opinions,

and especially Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of

Education, supra, that the hardships of the plan adopted

on the students being transported, the danger to the health

and safety of the children and the extreme difficulty of

complying with the plan, as exemplified by the staggered

hours and opening and closing of the schools, are all mat

ters which should be considered in determining whether

the plan or remedy adopted by the District Court is erro

neous. The anticipated hardships suggested to the Dis

trict Court became apparent when the plan was imple

mented, as shown by report filed with the District Court

by the director of schools, attached hereto as Appendix

“ D”. In the late fall and winter, according to the weather

bureau, the report shows the sun ries at 6:39 A. M. on

December 1 and sets at 4:32 P. M. In order to comply

with the plan formulated by the District Court it was

necessary that 133 school openings be staggered to begin

at thirty minute intervals from 7 A. M. to 10 A. M., and

closings staggered at thirty minute intervals with the lat

est schools let out at 4 P. M. and 4:30 P. M. Buses serv

ing schools opening at 7 A. M. begin their routes at 6:05

A. M., which is thirty-four minutes before sunrise on De

cember 1. Children must walk from their homes to desig

nated pick-up points, and consequently those picked up at

the beginning of the route may be on the street as much as

an hour before sunrise. Children who live within a mile

and a half of the school to which they are assigned (and

for whom buses are therefore not available) have to leave

home in time for 7 A. M. openings, necessitating many of

— 6 —

them walking to their designated school in darkness, and

of those attending schools opening at a later time some

will return home from school walking in darkness. In

many instances the report shows these children are walk

ing along streets without either street lights or sidewalks,

or street lights and no sidewalks or sidewalks and no

street lights (Appendix “ D”, pp. A-67-A-74).

The average time of a student on a bus transported

across town is forty-five minutes each way and the longest

period of time required for cross-town transportation is

one and one-half hours each way. Thus the average time

of a student on a bus transported across town is a total

of one and one-half hours of riding time and the longest

three hours of riding time. Twenty-eight thousand stu

dents are transported from the suburbs to the inner city

or vice versa each day, and approximately 400 round trips

are required across town daily by the 211 buses.

It thus results that the plan adopted by the District

Court and approved by the Court of Appeals has resulted

in substantial hardship to the children, both from the

point of view of time required to be on the bus and the

point of view of health and safety, and thus trespasses the

limits on school bus transportation indicated by this Hon

orable Court in the opinion on the application to stay in

the case of Winston-Salem etc. v. Catherine Scott et al.,

filed by the Honorable Chief Justice as the Circuit Justice

on August 31, 1971, and further the opinion of this Court

in the Swann case, 402 IT. S. 29-31.

Since Swann the test of a plan of integration is whether

it is feasible, workable, effective and realistic. A plan

which exposes children to the hardships enumerated above

cannot possibly meet any of these criteria.

7

Question 2

The plan formulated by the District Court and approved

by the Court of Appeals, as shown by the tables attached

to the District Court’s opinion (Appendix “ A” ), clearly

shows that the Court fixed a definite percentage of racial

mix, at least for elementary school children (Appendix

“ A ”, pp. A-21, A-24), from which there could be no de

viation lessening the percentage of mix. Apparently such

was predicated upon the same misconception of the hold

ing of this Honorable Court as was noted by Chief

Justice Burger in the Winston-Salem opinion on the ap

plication to stay, where the Chief Justice in referring to

the Swann case quoted in part as follows:

“ If we were to read the holding of the District Court

to require, as a matter of substantive constitutional

right, any particular degree of racial balance or mix

ing, that approach would be disapproved and we

would be obliged to reverse. The constitutional com

mand to desegregate schools does not mean that

every school in every community must always reflect

the racial composition of the school system as a

whole. ’ ’

Although the opinion of the District Court shows un

mistakably by its frequent reference to the Swann opinion

that the Court was attempting to be guided by it, the

result is that the: Court finds in formulating the plan and

order based thereon, especially with the elementary

schools, that a particular degree of racial balance or mix

was required as a matter of substantive constitutional

right.

This error was compounded, we respectfully submit, by

the Court of Appeals in affirming the District Court’s

judgment.

Question 3

It is the petitioner’s insistence that it is the duty of

the plaintiff in an alleged class action to sustain the ac

tion in compliance with Rule 23. Upon failure of the

plaintiff to do so, the defendant may challenge the action

as a class action. But whether either the plaintiffs or

the defendants challenge the action as a class action, or

the appropriateness of the class, Rule 23 requires a find

ing by the Court prior to judgment that the plaintiffs

will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class.

There was no such finding by the District Court, nor was

there a finding of who constituted the class.

This Honorable Court, on Monday, February 28, 1966,

entered its order approving amendments and additions to

the Rules of Civil Procedure which were to take effect

July 1, 1966, and were to govern all proceedings in actions

brought thereafter and in all further proceedings in ac

tions then pending, except to the extent that in the opin

ion of the Court application in a particular action then

pending would not be feasible or would work an injus

tice. Among the amendments and additions is the new

Rule 23 relating to class actions, subsection (c) of which

requires the District Court as soon as practicable after

the commencement of an action brought as a class action

to determine by order (emphasis ours) whether it is to be

so maintained. Such determination would require the

trial court to make findings contemplated by Rule 23(a),

(b) and (c), or a finding to the effect that the applica

tion of Rule 23 to a pending action was not feasible or

would work an injustice. No such order was entered in

these cases and no finding was in fact made, even though

only one named plaintiff remained in school at the time

of the trial of the cases in 1971, and this named plaintiff

was in senior high school. There was no plaintiff at the

time of the trial in 1971, representing the elementary

— 8 —

school grades or children, and none representing the

junior high school grades or children. There was no find

ing by the trial court of who constituted the class for

whose benefit the action was brought or that plaintiff

would adequately and fairly represent the interest of the

class, as required by Buie 23(c), but the relief ordered

was substantially different for the kindergarten and ele

mentary grades from that ordered for the junior and

senior high schools.

For example, at the elementary grade level the plan

required the cross-town transportation of black children

to white or predominantly white schools. The plan did

not require transportation of white children, at the ele

mentary grade level. The only plaintiff remaining in

school at the time of the trial of this case was in senior

high school. So it is that the elementary grades had no

representative before the Court to speak for them, not

withstanding the fact that the decree was to be binding

on the elementary grade students and res adjudicata of

their rights.

The District Court and the Court of Appeals, without

passing upon the validity of this requirement, simply

held that the same was waived by the plaintiff, whereas

the rule is directed to the duty of the Court and not the

duty of the parties. It is respectfully submitted that the

Court of Appeals erred in affirming the District Court’s

total disregard of Buie 23.

10 —

CONCLUSION

This petition for certiorari should therefore be granted

so that the meaning of Swann can be further clarified

and the application of Rule 23 to this proceeding be de

termined for the protection of the class in the future.

Respectfully submitted

K. HARLAN DODSON

DICK L. LANSDEN

1200 American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Attorneys for Metropolitan County

Board of Education of Nash

ville and Davidson County, Ten

nessee', C. R. Dorrier, Chairman,

et al.

Of Counsel

HOOKER KEEBLE DODSON & HARRIS

Nashville Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

WALLER LANSDEN DORTCH & DAVIS

1200 American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

HAMILTON GAYDEN, JR.

American Trust Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

APPENDIX

APPENDIX “ A”

MEMORANDUM OPINION

(Filed June 28, 1971)

History of Litigation

The original action seeking school desegregation of the

Nashville school system was filed in September, 1955.1

Finally, on July 16, 1970, after the gradual evol vein exit of

the present status of the law, this United States District

Court, speaking through the Honorable William E, Miller,

held that the local school hoard had not met its affirmative

duty to abolish the dual school system in three categories:

pupil integration, faculty integration, and site selection

for school construction. Kelley v. Metropolitan County

Board of Education, 317 F. Supp. 980 (M.D. Tenn. 1970).

The approval and implementation of a plan to correct the

adjudicated wrongs was delayed until the Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals ordered immediate hearings for that

purpose.

Background Data

The Metropolitan school system consists of three di

visions. The elementary schools accommodate students

from kindergarten through the sixth grade. Junior high

accommodates grades seven through nine. Senior high

consists of grades nine through twelve.

In the 1970-71 school year a total of 94,170 students at

tended the Metropolitan schools. Of this number, 33,485

were transported by the Metropolitan school system. Of

1 Reference to the separate and later consolidated actions re

garding the City of Nashville and Davidson County systems is

omitted for brevity.

A-2

tlie total transported, less than 4,000 were black and ap

proximately 30,000 were white.

One hundred forty-one schools were operated in the

Metropolitan school system during the 1970-71 school year.

The racial breakdown of the students was:

black ........................ . . . 23,533

white ......................... . . . 71,754

other ......... ......... . . . 237

The percentage breakdown was:

black ........................,.. 24.63%

white ......................... . .. 75.12%

other .........................,.. .25%

Plans Submitted for Court Approval

School Board Plan

The Board of Education submitted a plan for pupil in

tegration in August, 1970. Included in this plan was a

policy statement that the school board “ accepts as an

ideal student racial ratio of an integrated school as one

which is 15% to 35% black.”2

The August, 1970 plan made 49 minor geographic zone

changes, and provided for the transportation of an addi

tional 1162 pupils.3 The result of the plan was to leave

the elementary schools significantly unchanged. Six of

the 38 high schools and junior high schools would remain

at least 50 per cent black. Fifty-seven per cent of the

black high school and junior high school students would

2 The testimony of expert witnesses indicates that the ac

cepted and satisfactory norm is a range from 10 per cent below

-to 10 per cent above the percentage of black students enrolled

in a school system.

3 McGavock, a recently erected high school, was not included

in the August, 1970 plan.

— A-3

attend these six schools. The racial composition of two

schools would be at least 95 per cent black and four other

schools would be at least 90 per cent black. This would

result in 47 per cent of the black students attending

schools where the composition would be above 90 per cent

black. Eight schools, accommodating 20 per cent of the

black students, would operate with 15-35 per cent black

students. Fifteen schools would operate with 95 per cent

or above white students.

On the last day of the hearings, which were held on

several days over a three-month period, the school board

submitted an amendment providing for the selection of

students for McGavock School by paring.

Plaintiffs’ Plan

Elementary Schools. Plain tiffs, through clustering and

pairing, using both contiguous and non-contiguous zoning,

proposed to effect in most elementary schools, through two

alternate plans, a mathematical ratio in the range of 15-35

per cent black. Plan I would require the transportation

of 25,500 elementary students, and Plan II would require

the transportation of 27,000 pupils. Eighty-two of 100

schools would fall within the ideal ratio under Plan I,

while under Plan II, 91 schools would attain the indicated

ratio.

Secondary Schools. A model was submitted which in

cluded sectoring, clustering and pairing to attempt to at

tain 15-35 per cent black in the junior and senior high

schools. In both the elementary and secondary school

plans there is not a satisfactory description of grade

organization, structuring of the schools, the assignment of

the pupils, or definite zone description. The plans propose

the mathematical result indicated, but delegate to the

school board the actual assignment of pupils and imple

mentation of the plan.

— A -4—

HEW Plan A as Amended4

At the request of the Court, the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare submitted a plan with two alter

nates. The principal plan was designated as Plan A.

This plan incorporates geographic zone changes, cluster

ing, pairing (both contiguous and non-contiguous), and

grade restructuring.

Elementary Schools, Five schools would be closed.5 Sev

enty-four schools would have a racial percentage of 16-41

per cent black. Twenty-two schools which are located in

the far reaches of the county would have a racial percent

age of 0-11 per cent black. Three of those 22 would have

no blacks. Under Plan A there would be no elementary

school in the system with a black student enrollment of

more than 41 per cent. Fifty-nine per cent of the black

students in the system would attend schools with a black

student enrollment of between 35 and 41 per cent. Three

per cent of the black students in the system would attend

schools with a black student enrollment of less than 15

per cent. Twenty-four per cent of the total number of

white students in the system would attend schools in which

black enrollment is less than 5 per cent. One per cent of

the total black student enrollment in 16 schools, or 125

students, would be enrolled in schools with less than 5

per cent black student enrollment.

Under this plan, approximately 22,000 elementary school

students would be eligible for school-provided transporta

tion. This is approximately 10,500 more than the Board

4 Adjustments were made to shorten transportation routes,

to incorporate the school hoard plan for McGavoek School, to

adjust the student makeup of Pearl High School.

5 Three of the five schools to he closed are rated unsatisfac

tory by the consultants hired hy the school board. The other

two are listed as inadequate.

transported in 1970-71, and 9,700 more than those who

would be transported under the Board’s proposed plan.

Three thousand five hundred fewer students would be

transported under HEW Plan A than under the plaintiffs’

Plan I, and some 5,000 fewer than would be transported

under plaintiffs’ Plan II.

Junior High Schools. This plan incorporates the school

board amendment to the August, 1970 plan. Eighteen of

25 schools would have a racial composition of 20-40 per

cent black. Seven schools would have a composition rang

ing from 0-5 per cent black. These seven schools are in

the outer reaches of the county. Some former senior high

schools would be changed to junior high schools. Two

high schools would be closed.

Senior High Schools. This plan incorporates the school

board amendment to the August, 1970 plan. Central High

School would be closed. MaGavock High School is to be

opened. Of the 18 schools, 11 would have 18-44 per cent

black. One would have an 11 per cent enrollment of

blacks and six would be virtually all white. These all-

white schools are located in the outer reaches of the

county.

An analysis of the HEW amended plan with regard to

the secondary schools reflects that:

(1) no school would operate with more than 44 per cent

black;

(2) 29 of the 43 schools would operate within the range

of 15-44 per cent black, with one additional school having

11 per cent black;

(3) 13 schools, primarily in the outer reaches of the

county, would have 95 per cent or more white;

(4) 67 per cent of the schools, housing 90 per cent of

the black students, would operate ip the 15-44 per cent

black range;

— A-6 —

(5) transportation would be required for 26,673 junior

and senior high school students; and

(6) including the transportation necessary for Mc-

Gavoek School, 2,838 more secondary pupils would re

quire transportation than were transported in the 1970-71

school year.

Objective, Test, and Methods

Objective

“ The objective today remains to eliminate from

public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segrega

tion.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Ed

ucation, .. . U.S. . . . , 28 L.Ed.2d 554, 566 (April 20,

1971).

The Supreme Court has stated that “ [t]he objective is

to dismantle the dual school system,” Swann, supra, at

573, “ . . . to eliminate invidious racial distinctions,”

Swann, supra, at 568, and “ . . . t o achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation, taking into ac

count the practicalities of the situation.” Davis v. Board

of School Commissioners, . . . U.S. . . . , 28 L.Ed.2d 577,

581 (April 20, 1971),

Test

A plan “ that promises realistically to work, and prom

ises realistically to work now” is required. Davis, supra,

at 581, quoting Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S.

430 (1968). A plan “ is to be judged by its effectiveness.”

Swann, supra, at 572; Davis, supra, at 581. A plan “ is

not acceptable simply because it appears to be' neutral.”

Swann, supra, at 573.

Methods to Accomplish Objective

The following methods have been acknowledged by the

United States Supreme Court: (1) restructuring of at

tendance zones, both contiguous and non-contiguous; (2)

A-7 -

restructuring of schools; (3) transportation; (4) sector

ing; (5) non-discriminatory assignment of pupils; (6)

majority to minority transfer; and (7) clustering, group

ing and pairing. Swann, supra-, Davis, supra.

Discussion of Plans Submitted

The pupil integration plan submitted by the school

board, viewed in the most favorable light, constitutes

mere tinkering with attendance zones, and represents only

a token effort. It clearly falls short of meeting the ob

jectives and tests set out in the decisions of the United

States Supreme Court. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, supra-, Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners, supra-, Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430 (1968). In effect, the defendant has made no

effort to meet its affirmative duty to establish a unitary

school system “ in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.” 6 * 8 Green v. County School

6 Based on defendants’ school statistics for 1969-70, the stu

dent enrollment was 95,789. The total majority to minority re

zoned under this plan is:

Elementary

whites gained in black schools 301

blacks gained in white schools 457

758 majority to minority

transfer in

elementary

Junior High

whites gained in black schools 430

blacks gained in white schools 400

830 majority to minority

transfer in junior

high

Senior High

whites gained in black schools 73

blacks gained in white schools 735

808 majority to minority

transfer in senior

high

— A-8

Board, supra, at 437-38; quoted in McDaniel v. Barresi,

. . . U.S. . . 2 8 L.Ed.2d 582, 585 (April 20, 1971).

Since the defendants have, in effect, failed to submit a

constitutionally sufficient plan, the Court must examine

the other plans. The plaintiffs’ plans as to elementary

schools are adequate in one respect. Under Plan I, 82

out of 100 schools would be within the indicated range

of 15-35 per cent black, which was set by the school

board. Plan II would satisfy this standard in 91 out of

100 schools. This plan, however, has two features which

are objectionable to the Court., The first is that actual

assignment of student, i.e., the locations from which they

come, is left to the school board. The historical reluc

tance by the school board to solve this problem instills

a lack of confidence in their implementation of this aspect

without close supervision. The second objection is that

some schools in the outer reaches of the county are in

cluded. The Court finds that costs and other problems

incident to transportation make this feature of plaintiffs’

plan impractical and not feasible.

Each and every school is not required to be integrated.

The test is a unitary school system. Swann, supra. The

practicality and feasibility of a plan is a material con

sideration. Swann, supra.

The cost of the transportation of students and the un

necessary disruption of the students are proper consid

erations. The Court finds that distance and transporta

tion difficulties make the integration of these schools

highly impractical.

Plaintiffs plan for the desegregation of secondary

schools, as in their elementary plan, was a model using

sectoring, zoning (contiguous and non-eontiguous), and

pairing to accomplish the indicated racial balance. In

neither the elementary plan nor the secondary model is

there a description of grade organization, structuring of

— A-9 —

the schools, the assignment of pupils, or proper descrip

tion of zoning. For the reasons set forth as to the ele

mentary school programs, the secondary school plan of

the plaintiffs is rejected.

The plans of the plaintiffs and defendants being re

jected for the reasons stated, the HEW plan is the only

realistic plan remaining before the Court. As a result

of the evidence produced at the hearing, the HEW plan

was amended to effect the following changes:

(1) adjustment of the black percentage of North High

School from 65 per cent black to 44 per cent black, and

the reduction at Pearl High School to 33 per cent black,

with corresponding adjustments in Stratford, Maplewood,

and other schools;

(2) shortening the time of transportation of certain

pupils; and

(3) incorporation of the McGavoek High School phase

of the defendants’ amended plan.

On the last day of the hearings the defendants pre

sented an amendment to its August, 1970 plan. This

amendment provided that McGavoek would be a compre

hensive high school serving an area where several junior

high schools are located. Although this amendment ap

plied only to a small sector of the secondary school sys

tem, it reflected the beginning of an awareness by the

defendants of their affirmative constitutional responsibil

ity. The defendants indicate a desire to make similar

proposals in the future, which desire the Court wishes

to encourage. If the Board of Education had genuinely

wished to establish a unitary school system, it had avail

able to it the superior resources and assistance to do so.

The realistic and effective approach of the defendants

to the McGavoek School area was incorporated as an

amendment to the HEW plan, despite the fact that it

A-10 —

requires more transportation, over longer distances, than

was required by the original HEW plan. The Court feels

that where administrative goals can be satisfied without

hampering the constitutional objectives to be accom

plished, such goals should control.

Action of the Court

The Court hereby adopts the HEW Plan A as to ele

mentary schools. This plan utilizes all of the methods

previously enumerated. The map showing the geographic

zones is on file with the clerk. This map also reflects the

zoning, pairing and clustering to be employed. The charts

appearing at pages 34 through 41 of the HEW plan, as

filed with the clerk, are adopted as a part of said plan

and will be followed in the implementation thereof.

Simultaneously with this Memorandum Opinion, the

Court has filed maps showing the geographic zones of the

junior and senior high schools. Likewise, charts are filed

titled Table 1, Senior High Schools, and Table 2, Junior

High Schools. These charts will be followed in the im

plementation of the plan.

Li the implementation of the plans, the transparent

maps can be placed as overlays on the student locator

map. Thus the geographic boundaries of the zones be

come clear. In effect, the Court is providing the defend

ant school board a map overlay for each of the grade di

visions, namely the elementary schools, the junior high

schools, and the senior high schools. These overlays indi

cate grade and school groupings, where such are made,

and approximate areas for attendance. Accompanying

tables show the approximate numbers of pupils involved.

The responsibility for determining the precise boundary

lines is placed upon the defendant Board of Education.

A written description of such boundaries, together with

tables showing approximate numbers of pupils by race in

A -U —

each school, shall be filed with this Court by August 1,

1971. The defendant Board of Education may make minor

alterations in boundaries provided such alterations do not

lessen the degree of desegregation in the plan, ordered by

the Court.

The Court is aware that the cost of implementing any

plan is a major concern,. Much proof was introduced as

to the financial impact of any plan which requires trans

portation. Since the defendants have consistently trans

ported large numbers of students to promote segregation,

some adjustment must be made to reverse this unconsti

tutional practice. Practical solutions are available, such

as the multiple use of buses, staggered hours for school

opening, and staggered hours for individual grades.

“ We do not read Swann and Davis as requiring

the District Court to order the Board to provide ex

tensive transportation, of pupils to schools all over

the city, regardless of distances involved, in order

to establish a fixed ratio in each school.” Northcross

v. Board of Education, Civil Nos. 20,533, 20,539 (6th

Cir., filed June 7, 1971).

This order does not contemplate cross-transportation of

pupils within a grade level in implementation of this

order. If such crossing occurs, the Board may make

minor adjustments in, zones or may make application to

the Court for reconsideration of the zones. It is further

contemplated that the transportation routes in the plan

implemented by this order permit uninterrupted trans

portation of children from home pickup points to and

from the school attended. This is not to preclude the

Board in the exercise of administrative discretion and

consideration of transportation economics, from establish

ing transfer routing and collection points.

The Court is aware that some “ all-white” schools re

main in the outlying areas of the county. However, based

A-12

upon practical considerations, common sense and judg

ment dictate that they should not be integrated. Inte

gration of those particular schools would not be feasible,

both from a distance and a cost standpoint. However, to

prevent the use of these schools as an avenue of resegre

gation, certain restrictions on their use will be herein

after set forth.

Special Provisions

Majority to Minority Transfer Policy

After this plan is implemented, there will be no schools

which have a majority of black students. Because of

population changes or other circumstances, however, this

situation might occur in the future. Therefore, the fol

lowing policy shall be a part of the plan to be imple

mented.

Whenever there shall exist schools containing a ma

jority of black students, this school board shall permit

a student (black or white) attending a school in which

race is. the majority to choose to attend the closest school

where his race is a minority. The Board of Education

will provide all such transferring students free transpor

tation and will make space available in the school to

which he desires to move. The Board will notify all

students of the availability of such transfers.

Faculty Integration

On July 16, 1970, Judge Miller in this case stated:

“ It is well recognized that faculty and staff inte

gration is ‘an important aspect of the basic task of

achieving a public school system wholly free from

racial discrimination.’ United States v. Montgomery

County Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225, 89 S.Ct.

1670, 23 L.Ed.2d 263 (1969); see Bradley v. School

Board of City of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103, 86 S.Ct, 224,

A-13

15 L.Ed.2d 187 (1965). In order to implement this

mandate, the Court concludes that in the instant case

faculties must he fully integrated so that the ratio

of black and white faculty members of each school

shall be approximately the same as the ratio of black

to white teachers in the system as a whole. Robinson

v. Shelby County Board of Education, supra-, Nesbit

v. Statesville City Board of Education, 418 F.2d 1040

(4th d r . 1969); Stanley v. Darlington County School

District and Whittenberg v. Greenville County School

District, 424 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1970); Pate v. Dade

County School Board, 307 F. Supp. 1288 (S.D. Fla.

1969); contra, Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education,

supra. But see Goss v. Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville, 406 F.2d 1183 (6t,h Cir. 1969).”

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education,

supra, at 991.

% # # * * # #

“ It is the conclusion of the Court that the present

policy of faculty desegregation, applied by defendant

is constitutionally inadequate. That policy must be

altered to comply with the standards set forth above.

A similar policy also must be applied to all other

personnel employed by defendant school board.”

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education,

supra, at 992.

The court-required ratio for teachers in each school

was fixed at that time to be 80 per cent white to 20 per

cent black. Approximately 94 schools are not currently

operating at this ratio. In most schools, this ratio could

be accomplished by moving one or two teachers. Upon

the implementation of the plan presently adopted by the

Court, there should be no difficulty in meeting the court

order of 1970. Therefore, the defendants are required to

effect said ratios for the next school year beginning on

or about September 1, 1971.

The school board shall immediately announce and im

plement the following policies':

1. The principals, teachers, teacher-aides, and other

staff who work directly with children at a school

shall be so assigned that in no case will the racial

composition of a staff indicate that a school is in

tended for black students or white students. The

school board shall, to the extent necessary to carry

out this desegregation plan, direct members of its

staff to accept new assignments as a condition to

continued employment.

2. Staff members who work directly with children,

and professional staff who work on the administra

tive level will be hired, assigned, promoted, paid,

demoted, dismissed, and otherwise treated without

regard to race, color, or national origin.

3. If there is to be a reduction in the number of

principals, teachers, teacher-aides, or other profes

sional staff employed by the school system which will

result in a dismissal or demotion of any such staff

members, the staff member to be' dismissed or demoted

must be selected on the basis of objective and reason

able non-discriminatory standards from among all the

staff of the school system. In addition, if there is any

such dismissal or demotion, no staff vacancy may be

filled through recruitment of a person of a race, color,

or national origin different from that, of the individual

dismissed or demoted, until such displaced staff mem

ber who is qualified has had an. opportunity to fill the

vacancy and has failed to accept an offer to do so.

Prior to such a reduction, the school board will de

velop or require the development of nonracial objec

tive criteria to be used in selecting the staff member

who is to be dismissed or demoted. These criteria

— A-14 —

A-15 —

shall be available for public inspection and shall be

retained by the school board. The school board also

shall record and preserve the evaluation of staff mem

bers under the criteria. Such evaluation shall be

made available upon request to the dismissed or de

moted employee.

“ Demotion” as used above includes any reassign

ment (1) under which the staff member receives less

pay or has less, responsibility than under the assign

ment he held previously, (2) which requires a lesser

degree of skill than did the assignment he held previ

ously, or (3) under which the staff member is asked to

teach a subject or grade other than one for which he

is certified or for which he has had substantial ex

perience within a reasonably current period. In gen

eral, depending upon the subject matter involved,

five years is such a reasonable period.

Construction, Renovation and Location of Schools

On July 16, 1970, the United States District Court

stated:

“ The constitutional requirement of desegregation

also finds application in the area, of construction,

renovation, and location of schools. School boards are

required consciously to plan school construction and

site location so as to prevent the reinforcement or

recurrence of a dual educational system. See, e.g.,

Felder v. Harnett County Board of Education, 409

F.2d 1070 (4th Cir. 1969); Swarm, v. Charlotte-Meck-

lenburg Board of Education, 306 F. Supp. 1291, 1299

("W.D. N.C. 1969); Pate v. Dade County School Board,

307 F. Supp. 1288 (S.D. Fla. 1969). Courts may prop

erly restrain construction and other changes in the

location or capacity of school properties until a show

A-16

ing is made that such changes will promote rather

than frustrate the establishment of a unitary school

system. This Court in the past has stated that school

boards may be enjoined from planning, locating or

constructing new schools or additions to existing

schools in such manner as to conform to racial resi

dential patterns or to encourage or support the growth

of racial segregation in residential patterns. Such

operations, rather, are to be conducted ‘in. such man

ner as to affirmatively promote and provide for both

the present and future an equitable distribution of

racial elements in the population of each School Sys

tem. ’ Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson

County, Civ. No. 3107 (M.D. Te-nn., Oct. 16, 1969).

“ Looking to the facts of the instant case, it be

comes apparent that defendant’s decisions, on the site

selection and construction of its newest schools were

not designed to promote desegregation. Since 1963,

defendant has built four new elementary schools

(Dodson, Cranberry, Lake View, and Paragon Mills),

eight new junior high schools (Apollo, Bass, Ewing

Park, McMurray, John T. Moore, Neely’s Bend, Bose

Park, and Wright), and one new high school (Du

pont). Of these 13 schools, Bose Park, with an en

rollment of 527 black students and 11 white students,

is virtually all-Negro. The remaining twelve schools,

however, are, on the average, 97% white, with some-

having a black enrollment as high as 10%. Three

elementary schools (Cora, Howe, Fall-Hamilton, and

H. G. Hill) and. one- high school (McGavock) are- cur

rently under construction. Enrollment estimates indi

cate that all of these schools will be predominately

white.

“ Seven elementary schools, two high schools, and

one school for the physically handicapped, are cur-

A-17 —

rently in the planning stage. The two high schools

are being planned for predominantly black student

bodies. Five of the seven elementary schools are to

be constructed in virtually all-white residential areas,

while the remaining two are projected for location

in all-black or predominantly black residential areas.

Thus, from the foregoing, it is apparent to the Court

that defendant must consider making substantial al

terations in its school construction policies in order

to comply with constitutional requirements.

“ The Court is of the opinion that the following

course of action must be taken by defendant. First,

those new schools on which construction work was

actually in progress as of November 6, 1969,13 may be

completed. Though this action may not produce an

ideal result in light of the goal of integration, it will

prevent unnecessary economic waste. Also, since,

these new schools will be subject to the same zoning

policies prescribed above, their segregative influences

should be lessened. Second, in instances where actual

construction had not begun as of November 6, 1969,

defendant must revise its plans where necessary in

relation to these proposed schools so as to find a loca

tion that will maximize student integration. Finally,

in the future all construction plans as well as plans

for closure of old schools must be governed by the

principles stated herein. The purpose of the Court in

making such a requirement is to insure that such plans

will serve the purpose of establishing a unitary school

system. See Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson

County, supra.” (Footnote omitted.) Kelley, supra,

at 992-93.

“ !3 This is the date of the Temporary Restraining Order

issued by this Court to enjoin defendant from further con

struction, expansion, or closure of schools pending the out

come of this suit.”

A-18 —

New Construction. The Board has proposed for approval

the erection of two comprehensive senior high schools, one

in the Joelton school area, and the other in the Goodletts-

ville area.

In connection with future planning, the Board employed

a team of consultants to evaluate the existing school

structures and to project the location of new structures.

Prior to the submission of these recommendations, the

Court requested, and two administrators of the Board lo

cated on a map, the ideal locations for comprehensive

schools. When the team of consultants later made its re

port, their projections generally agreed with those of the

school administrators. They found that new comprehen

sive schools should be located in the general area of the

proposed inner-city expressway loop known generally as

“ Briley Parkway.” The reason for this agreement is

obvious when the pupil locator map is examined. Briley

Parkway is generally the divider between the inner-city

pupils and the outer-county pupils. It is roughly the half

way division. By the establishment of schools in this

area, the integration of schools would be effected naturally

and thereby minimize transportation.

Therefore, the Court finds that the erection of a compre

hensive school in the Joelton area, with geographic zones

drawn in accordance with the testimony in court, will

maximize student integration. Upon submission of proper

zoning and pupil assignment, this construction will be

approved.

The proposed Goodlettsville school, a comprehensive

high school, is located in an all-white community and is

not located near the dividing line between inner-city popu

lation and outer-county population. By referring to the

pupil locator map, it clearly appears that the erection of

this school would tend to promote segregation. Thus the

erection of this school in its proposed location is hereby

A-19

enjoined. If the Board desires to establish another com

prehensive high school, subsequent court approval may be

obtained by submitting an appropriate location and proper

geographic zones, which will achieve and perpetuate inte

gration.

Another proposal is the erection of a school for the

physically handicapped at 2500 Fairfax Avenue. This

facility is to be erected near Vanderbilt University. The

availability of professional services from Vanderbilt Uni

versity and Vanderbilt Hospital is stressed. The plaintiffs

assert that said project should be located in a “ halfway”

position between Vanderbilt University, Meharry Medical

College, and Fisk University.

The Court feels that the facility will have little, if any,

effect on achieving a unitary school system. This Court

will not substitute its judgment for that of the Board, and

the Board’s proposal is approved.

Additions and Renovations. An application has been

made for permission to acquire additional property for

Hillsboro School so as to transform Hillsboro into a com

prehensive high school. This application is denied for

the same reasons that the Goodlettsville school was not

approved.

Portable classrooms, referred to generally as “ port

ables,” have been used by the Board to house students in

schools which were all-white or had received only token

integration when there were vacant rooms in predomi

nantly black schools. In effect, portables have been used

to maintain segregation. In the future, portables shall be

used only to achieve integration and the Board is hereby

so enjoined.

In the plan adopted by the Court, certain schools in the

outlying areas of the school district remain virtually all

white. By reason of the past conduct of the Board the

— A-20 —

Court hereby sets forth the following restrictions to pre

vent these schools from becoming vehicles of resegrega

tion. It is ordered that the schools, which have less than

15 per cent black pupils after the implementation of the

plan, shall not be enlarged either by construction or by

portables, and shall not be renovated without prior court

approval. Furthermore, no additional schools shall be

erected without prior court approval.

By making the above restrictions, this Court does not

imply that it will make “ year-by-year adjustments of the

racial composition of student bodies once the affirmative

duty to desegregate has been accomplished and racial dis

crimination through official action is eliminated from the

system.” Swann, supra, at 575.

The parties will draw and submit an order to the Court

within fifteen (15) days. However, without said order

this Memorandum Opinion is self-executing and must be

implemented for the school year beginning on or about

September 1, 1971. The Court will retain jurisdiction of

this case. No stay will be granted by this Court. Swann,

supra, at 570; United States v. Board of Public Instruc

tion. 395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968); Brewer v. School Board,

397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

L. CLURE MORTON

United States District Judge

A-21

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Date.......................

Students

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS. W N T %B

McKissack 5-6 990 516 482 373 955 39

McCann 1-4 690 108 417 273 690 39

Cockrill 1-4 510 0 241 36 277 36

Charlotte Park 1-4 870 164 556 306 862 36

Riehland 1-4 510 136 241 136 377 36

Park Avenue 5-6 420 272 277 111 388 29

Sylvan; Park 1-4 660 164 340 157 497 32

Vaught 1-4 360 114 212 114 326 35

Head 5-6 1080 350 329 211 540 39

Ransom 1-4 390 202 252 154 406 38

Eakin 1-4 570 130 238 145 383 38

Woodmont 1-4 360 205 204 128 332 38

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Students

%BName! of School Grades CAP. TRANS. W N T

W averly-Belmont 5-6 450 294 310 160 470 34

Stokes 1-4 390 67 157 91 248 37

Burton 1-4 540 316 234 137 371 37

J. Green 1-4 390 128 251 90 341 34

Percy Priest 1-6 660 519 471 188 659 28

Robertson Academy 5-6 210 126 138 55 193 28

Glendale 1-4 420 246 263 99 362 27

C.; Lawrence 6 1020 283 308 160 468 34

Murrell 5 510 272 279 161 440 37

Fall-Hamilton 1-4 480 86 245 168 461 36

Berry 1-4 450 114 207 115 322 36

Woodbine 1-4 510 144 248 143 391 36

Turner 1-4 630 139 247 129 376 34

Glenelifi 1-4 480 133 254 129 383 34

Comments

Contiguous

Contiguous

306-b from A

136-8 from B

Contiguous

114-b from C

153 b from D

Contiguous

128 b from E

Comments

Contiguous

18w-137b from H

16w-90-b from G

12-w-188-b from F

Contiguous

l-w-113b from L

l-w-143-b from J

8w-129b from I

4-w-128bi from K

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Date.......................

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS. W

Students

N T %B Comments

Napier 6 780 289 289 183 472 39

Johnson 5 720 333 328 192 520 37

Allen 1-4 540 585 319 196 515 38 Contiguous

Glennview 1-4 630 241 371 235 606 39 6w-235b from M

Glengarry 1-4 360 146 211 140 351 39 140-b from N

Whitsitt 1-4 600 390 390 244 634 38 64-w-244b from 0

Early 5-6 840 367 370 188 558 34 N. C.

H. G. Hill 1-4 600 401 304 199 503 39 N. C.

Brookmeade 1-4 570 371 335 198 533 37 N. C.

Ford Green 5-6 1050 437 428 259 687 38 N. C.

Parmer 1-4 540 316 223 154 377 40 N. C.

West Meade 1-3 510 367 294 180 474 38 N. C.

Binkley 1-4 510 367 305 184 489 38 N. C.

P Mills

Date.......................

Name of School Grades

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Students

CAP. TRANS. W N T

FORM

%B Comments

Wharton 5-6 1590 426 429 179 608 29 N. C.

Binkley 1-4 840 248 486 224 710 32 N. C.

Crieve Hall 1-4 540 125 275 125 400 31 N. C.

Buena Vista 5-6 660 415 448 184 632 29 N. C.

McGavock 1-4 600 358 395 193 588 33 N. C.

Hickman 1-4 660 217 444 182 626 29 N. C.

Fehr 5-6 360 211 236 92 328 28 N.C.

Stanford 1-4 630 358 391 184 575 32 N. C.

Kirkpatrick 5-6 540 20 305 126 431 30

Warner 1-4 1020 0 663 302 965 31

Caldwell 5-6 1110 375 390 219 609 36 N. C.

Lockeland 1-4 630 252 397 238 635 38 238-b-14-w from

Rosebank 1-4 600 200 306 180 486 38 N.C.

A-23 —

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS.

Ross K-6 360 13

Howe K-6 720 1

Dan Mills 5-6 540 191

Dalewood 3-4 660 51

Inglewood 1-2 720 191

Cotton K-6 420 0

Glenn 5-6 630 324

Baxter 3-4 690 475

Tom, Joy 1-2 720 375

Haynes 5-6 900 280

Shwab 1-4 480 115

Gra-Mar 1-4 420 188

W

Students

N T % B Comments

195 89 284 31 No change

474 127 601 21 No change

325 115 440 26

400 116 516 22

408 147 555 27

315 114 429 26

411 238 649 37

434 245 679 36

408 240 648 37

293 173 466 87

359 133 492 27 Contiguous

265 110 375 29 (Illegible)

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS.

Kings Lane 5-6 660 409

Brick Church 1-4 690 302

A, Green 1-4 300 112

Bellshire 1-4 570 132

Bordeaux 1-6 690 153

Jordonia 4-6 240 160

Wade 1-3 240 155

*Chadwell 1-6 480 212

*Stratton 1-6 780 212

Students

W N T %B Comments

405 229 634 36

417 295 715 41 Contiguous

187 109 296 37 106-b-7-w from W

221 129 359 37 128-b-2-w from X

494 186 680 27 No Change

155 46 201 23

171 41 212 19

405 135 540 25 * These schools include

694 129 823 16 former enrollment from

Jones in: grades 1-4

divided equally. Two-3

portables will be needed

at each school.

— A-24

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Date....................................................

Students

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS. W N T %B

Harpeth Valley K-6 600 460 555 15 570 3

Granberry K-6 660 402 569 37 606 6

Tusculum 1-6 630 0 601 19 620 3

Cole 1-6 780 273 693 13 706 2

Haywood 1-6 600 84 477 64 541 11

Paragon' Mills 1-6 930 366 851 1 852 .1

Una K-6 630 486 623 20 643 3

Lakeview 1-6 840 258 778 24 802 2

Dodson K-6 690 586 695 53 748 7

Hermitage 1-6 810 0 826 0 826 0

A. Jackson K-6 570 161 359 72 431 16

Pennington K-6 600 171 586 4 590 .6

N eely’s Bend 1-6 480 300 404 39 443 8

Donelson K-6 570 154 427 3 430 .6

DuPont 1-6 780 310 634 19 653 3

Table 4

COMPOSITE BUILDING INFORMATION FORM

ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

Date............................. ......................

Students

Name of School Grades CAP. TRANS. W N T %B

Amqui 1-6 660 100 673 3 676 .4

Old Center K-6 540 228 443 1 434 .2

Gateway 1-6 300 202 508 2 510 .4

Goodlettsville K-6 540 221 520 30 550 5

Union Hill 1-6 210 145 190 0 190 0

Joelton 1-6 390 346 398 0 398 0

Narny 1-6 330 150 189 0 189 0

Social (Illegible) Schools Unchanged

Total Transported.......................22,065

(Illegible)

(Illegible)

(Illegible)

Pearl Discontinued

Penard Discontinued

Siemens Discontinued

Elliott Discontinued

Jones Discontinued

Comments

Comments

A-25 —

APPENDIX “ B”

Nos. 71-1778-79

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

Robert W. Kelley, et al., Henry '

C. Maxwell, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

Metropolitan County Board of Ed

ucation of Nashville and David

son County, Tennessee, C. R.

Dorrier, Chairman, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

A p p e a l , from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Middle District of

Tennessee, Nash

ville Division.

Decided and Piled May 30, 1972

Before: E dwards, Celebeezze and McCbee, Circuit Judges

E dwards, Circuit Judge. In this case we do not write on

a clean slate. What follows describes an incredibly lengthy

record and settled law pertaining to segregated schools.

We start with this latter, as recited in the United States

Constitution and in three historic, unanimous decisions of

the United States Supreme Court—the last dated 1971.

“ [N]or shall any State . . . deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.” U.S. Const, amend. XIY, § 1.

— A-26

We conclude that in the field of public education the

doctrine of “ separate but equal” has no place. Sepa

rate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others simi

larly situated for whom the actions have been brought

are, by reason of the segregation complained of, de

prived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954).

[A] plan that at this late date fails to provide

meaningful assurance of prompt and effective dis

establishment of a dual system is also intolerable.

“ The time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out,”

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 IT. S. 218, 234;

“ the context in which we must interpret and apply

this language [of Brown II] to plans for desegrega

tion has been significantly altered.” Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U. S. 683, 689. See Calhoun v. Lati

mer, 377 U. S. 263. The burden on a school board

today is to come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work, and promises realistically to

work now. Green v. County School Board of Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 438-39 (1968).

All things being equal, with no history of discrimi

nation, it might well be desirable to assign pupils to

schools nearest their homes. But all things are not

equal in a system that has been deliberately con

structed and maintained to enforce racial segregation.

The remedy for such segregation may be administra

tively awkward, inconvenient, and even bizarre in some

situations and may impose burdens on some; but all

awkwardness and inconvenience cannot be avoided in

the interim period when remedial adjustments are

being made to eliminate the dual school systems.

— A-27 —

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 28 (1971).

After 17 years of continuous litigation the Metropolitan

County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson

County, Tennessee, appeals from a final order of the

United States District Court for the Middle District of

Tennessee requiring the School Board to take the neces

sary steps to end the racially separated school systems

which it had previously been found to be operating. This

order was a direct result of an order of this court approv

ing the District Court’s findings of violations of equal pro

tection and vacating a stay of proceedings. In it we had

noted:

[T]he instant case is growing hoary with age. It is

actually a consolidation of two cases. The first case,

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

Civ. A. No. 2094, was filed in September of 1955; and

the second case, Maxwell v. County Board of Educa

tion of Davidson County, Civ. A. No. 2956, was filed

in September of 1960. A whole generation of school

children has gone through the complete school system

of Metropolitan Nashville in the intervening years

under circumstances now determined to have been

violative of their conditional rights. A second gener

ation of school children is now attending school un

der similar circumstances—and the remedy is not in

sight. Kelley v. Metropolitan Board of Education of

Nashville, Tennessee, 436 F.2d 856, 858 (6th Cir.

1970).

The order of the District Judge is the first comprehen

sive and potentially effective desegregation order ever

entered in this litigation. The District Judge tells us that

now the remedy is at least in sight.

— A-28 —

THE APPELLATE ISSU ES

On appeal defendants contend 1) that the District Court

had no jurisdiction to hear and determine this case be

cause of failure to comply with Rule 23 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure and because of changes in the

status of the original party plaintiffs since the commence

ment of these suits; 2) that the District Court’s order is

invalid because it requires integration of schools accord

ing to a fixed racial ratio, in violation of the rules set out

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education,

supra at 23, 24; and 3) that the plan ordered into effect

should be reconsidered because of what the defendant

School Board claims to be adverse effects on the health

and safety of school children involved.

Plaintiffs as cross-appellants claim 1) that the District

Court erred in adopting the Department of Health, Edu

cation and Welfare plan when the plan proposed by

plaintiffs would have achieved a g r e a t e r degree of inte

gration; and 2) that the HEW plan should have been

rejected because it places the burden of desegregation

disproportionately upon Negro children.

HISTORY OF THE NASHVILLE-DAVIDSON

COUNTY CASE

The history of school desegregation from Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, to date can be traced in this

case in the proceedings in the District Court, in this Court,

and in the United States Supreme Court: Kelley v. Board

of Education of City of Nashville, 139 F.Supp. 578 (M.D.

Tenn. 1956) (Dissolution of three-judge court) • Kelly v.

Board of Education of City of Nashville, 159 F.Supp. 272

(M.D. Tenn. 1958) (Disapproval of integration plan and

grant to Board of additional time to file a new plan); Kel

A-29 —

ley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, 8 R.R.L.R.

651 (M.D. Term. 1958) (Approval of 12-year plan); Kelley

v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, 270 F.2d 209

(6th Cir. 1959) (Upholding District Court order); Kelley

v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, 361 U.S. 924,

80 S.Ct. 293, 4 L.Ed.2d 240 (1959) (Denial of certiorari);

Maxwell v. County Board of Education of Davidson

County, 203 F.Supp. 768 (M.D. Tenn. 1960); Maxwell v.

County Board of Education of Davidson County, 301 F.2d

828 (6th Cir. 1962), reversed in part and remanded sub

nom, Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683, 83 S.Ct. 1405, 10 L,Ed.2d 632 (1963); Kelley v. Board

of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, 293 F.

Supp. 485 (M.D. Tenn. 1968) (Further proceedings in a

consolidation of Maxwell, supra, and Kelly, supra); Kelley

v. Metropolitan County Board of Education, 317 F.Snpp.

980 (M.D. Tenn. 1970); Kelley v. Metropolitan Board of

Education of Nashville, Tennessee, 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir.

1970) (Memorandum opinion (filed June 28, 1971); Judg

ment (filed July 15, 1971)).

This case began in 1955 on the heels of the United States

Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra, holding that “ separate educational facilities

are inherently unequal,” supra at 495. Plaintiffs in a

class action sought invalidation of the Tennessee school

laws, T.C.A., § 49-3701, et seq., which in specific terms re

quired segregation of school pupils by race. (See Appen

dix A) In 1956 a three-judge federal court which had

been convened to pass on the constitutionality of the state

statute was dissolved when the defendant Board of Edu

cation conceded the unconstitutionality of the state statute

by which it had previously been governed. Kelley v. Board

of Education of City of Nashville, 139 F.Supp. 578 (M.D.

Tenn. 1956). The case was then remanded to the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Tennes

see. The District Judge determined that the case was an

— A-30

appropriate class action under Rule 23 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure (Record, Min. Book 19 at 683).

He ordered the defendant School Board to prepare and

present a plan for desegregation of the Nashville schools.

Before judgment was entered, the State of Tennessee

in January 1957 adopted a Parental Preference Law, TCA

§ 49-3704, Pub. Acts 1957, cc 9-13, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 215

(1957). (See Appendix A) This statute provided for sep

arate white, black, and mixed schools, with attendance to

be determined by parental preference. The District Court

in September of 1957 held this statute to be unconstitu

tional on its face. 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 970 (1957).

The defendant School Board thereupon (and nonethe

less) presented a parental preference plan for white,

black, and mixed schools substantially the same as that

called for by the unconstitutional state law.

In February of 1958 the District Court held the School

Board plan to be unconstitutional.

Later in the same year a grade-a-year desegregation

plan was submitted by defendant School Board, approved

by the District Court and the Court of Appeals, with

certiorari denied by the United States Supreme Court.

In 1960 a suit was filed to desegregate the Davidson

County schools. Maxwell v. County Board of Education

of Davidson County, supra. It was brought on behalf of

Negro children alleged to he denied their constitutional

rights to equal education in the county school system.

Again the suit was brought as a class action and recog

nized as such by the District Court under Rule 23, F ed. R.

Civ. P. (Record, Min. Book 24 at 114.) The Davidson

County school Board proposed a free transfer plan and

it was approved by the District Court. On appeal Max

well’s free transfer plan was invalidated by the United

States Supreme Court, sub nom., Goss v. Board of Edu

cation of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963).

A-31 —

In 1963 the school systems of Nashville and Davidson

County were then consolidated as part of a general con

solidation of the City of Nashville and County of David

son into one metropolitan government. Petitions for fur

ther relief, including an order to desegregate the Nash-

ville-Davidson County schools and to enjoin further school

construction pending such an order, were filed in the

consolidated case, with additional plaintiffs intervening.

In 1968 the United States Supreme Court took further

note of how the Brown II phrase “ deliberate speed” was

being employed to delay rather than to implement school

desegregation.

For purposes of reemphasis, we again quote the unani

mous opinion:

[A] plan that at this late date fails to provide

meaningful assurance of prompt and effective dis

establishment of a dual system is also intolerable.

“ The time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out,”

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234;

“ the context in which we must interpret and apply

this language [of Brown II] to plans for desegrega

tion has been significantly altered.” Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 683, 689. See Calhoun v. Latimer,

377 U.S. 263. The burden on a shool board today is

to come forward with a plan that promises realisti

cally to work, and promises realistically to work now.

Green v. County School Board of Kent County, 391

U.S. 430, 438-39 (1968). (Emphasis added.)

. On the heels of these deisions plaintiffs sought relief

consistent with them and lengthy hearings followed. In

1970 the District Judge entered findings of fact which

were subsequently reviewed and given effect by this court.

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of

Nashville, Tennessee, 436 F.2d 856 (1970). In its opinion

this court said:

— A-32

It would be well for those in authority in Nashville

and Davidson County to read the able opinion [Dis

trict Court opinon entered July 16, 1970] whch we

now revitalize by our present order. The emphasis

in the quotation which follows is that of this court:

“ [I]t is the Court’s view that in the area of

school zoning, school boards will fulfill their af

firmative duty to establish a unitary school sys

tem only if attendance zone lines are drawn in

such way as to maximize pupil integration. In

drawing such lines, the defendant school board

may properly consider in the total equation such

factors as capacities and locations of schools,

physical boundaries, transportation problems, and