Defendant-Intervenors' Notice of Appeal

Public Court Documents

March 13, 2000

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Defendant-Intervenors' Notice of Appeal, 2000. 74509ab6-e70e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7975e5e2-2509-4530-9ab9-54b3ebe896f9/defendant-intervenors-notice-of-appeal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

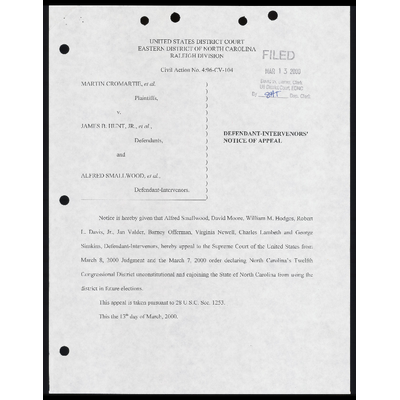

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4:96-CV-104

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.

Plaintiffs,

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et al.,

DEFENDANT-INTERVENORS’

Defendants, NOTICE OF APPEAL

ALFRED SMALLWOQOD, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Notice is hereby given that Alfred Smallwood, David Moore, William M. Hodges, Robert

L. Davis, Jr., Jan Valder, Barney Offerman, Virginia Newell, Charles Lambeth and George

Simkins, Defendant-Intervenors, hereby appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States from

March 8, 2000 Judgment and the March 7, 2000 order declaring North Carolina’s Twelfth

Congressional District unconstitutional and enjoining the State of North Carolina from using the

district in future elections.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sec. 1253.

This the 13" day of March, 2000.

.@ ®

Respectfully Submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel and President

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

TODD A. COX

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 1 Street, N.W., 10th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

ADAM STEIN

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins

® Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

312 West Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27516

(919) 933-5300

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that true and correct copies of Defendant-Intervenors’ Notice of Appeal

have been served by first-class mail, postage prepaid to the following:

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.

Chief Deputy Attorney General

Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602-0629

Robinson O. Everett

Everett & Everett

Post Office Box 586

Durham, North Carolina 27702

This 13th day of March, 2000.

° JZ Th

rg

Adam'Stein