Court Voids Extended Terms for County Commissioners

Press Release

April 26, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Court Voids Extended Terms for County Commissioners, 1966. b25d3df0-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79b56fe7-3f08-4d6d-b517-20be2c18f981/court-voids-extended-terms-for-county-commissioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

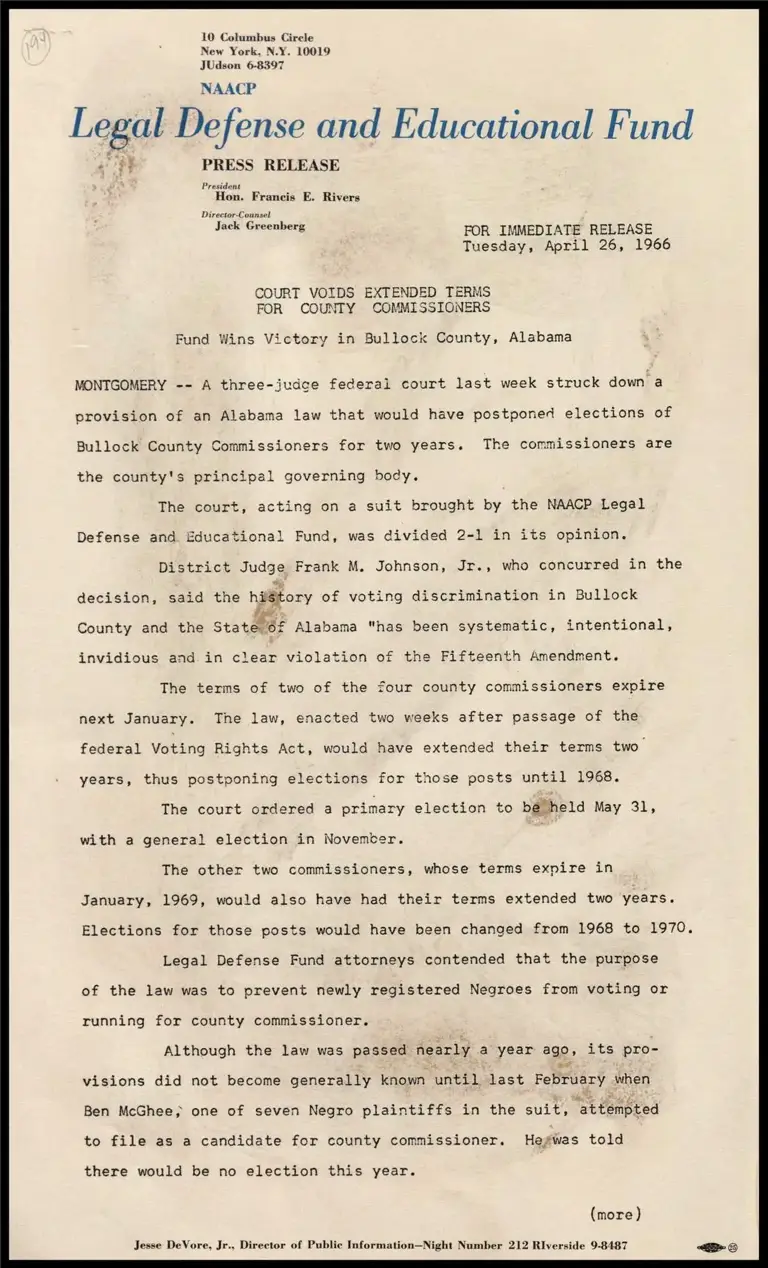

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Lega? Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President

Hon. Francis E. Rivers

Director-Counsel

Jack Greenberg FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Tuesday, April 26, 1966

COURT VOIDS EXTENDED TERMS

FOR COUNTY COMMISSIONERS

Fund Wins Victory in Bullock County, Alabama

MONTGOMERY -- A three-judce federal court last week struck down a

provision of an Alabama law that would have postponed elections of

Bullock County Commissioners for two years. The commissioners are

the county's principal governing body.

The court, acting on a suit brought by the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, was divided 2-1 in its opinion.

District Suds 4 Frank M. Johnson, Jr., who concurred in the

decision, said the hitory of voting discrimination in Bullock

County and the states Alabama "has been systematic, intentional,

invidious and in clear violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.

The terms of two of the four county commissioners expire

next January. The law, enacted two weeks after passage of the

federal Voting Rights Act, would have extended their terms two.

years, thus postponing elections for those posts until 1968.

The court ordered a primary election to be held May 31,

with a general election in November.

The other two commissioners, whose terms expire in

January, 1969, would also have had their terms extended two years.

Elections for those posts would have been changed from 1968 to 1970.

Legal Defense Fund attorneys contended that the purpose

of the law was to prevent newly registered Negroes from voting or

running for county commissioner.

Although the law was passed nearly a year age. its pro-

visions did not become generally known until last February when

Ben McGhee, one of seven Negro plaintiffs in the suit, “attempted

to file as a candidate for county commissioner. Hegwas told

there would be no election this year.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Publie Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487

aoe

Court Voids Extended Terms

For County Commissioners

The county has nearly twice as many voting age Negroes

as white, but only since passage of the Voting Rights Act have

Negro registered voters outnumbered whites.

Circuit Judge Richard T. Rives wrote the court's opinion.

He held that extension of the terms of incumbenetor fici als violated

a provision of the Voting Rights Law that forbids changes in the

voting qualifications and procedures that were in effect November

1, 1964. 4

Judge Johnson disagreed with Judge Rives that there was

no racial discrimination involved in the extension of the com-

missioners] terms. The history of discrimination against Negro

voters led him to "the firm conclusion" that the extension of

terms "was racially motivated," Judge Johnson said.

District Judge H. Hobart Grooms dissented.

Legal Defense Fund attorneys involved in the case were

Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg, Fred Wallace and Michael J.

Henry of New York and Fred Gray of Montgomery.

~/306=