17 Years Later, Marchers Retrace the Bloody Route of History News Clipping

Press

February 18, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. 17 Years Later, Marchers Retrace the Bloody Route of History News Clipping, 1982. b9fc3824-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79baf523-154b-422b-9345-cc0be034c178/17-years-later-marchers-retrace-the-bloody-route-of-history-news-clipping. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

J

A2 T~u,.dov. f,.hruorv 18. 1082 THE WASHINGTON POST

17 Years Later, Marchers Retrace the Bloody Route of ·History

By Art Harris

Wa.<hingU>n Post SIMI Writer

HAYNEVILLE, Ala., Feb. 17-

The civil rights marchers were com

ing his way again, but there was

nothing the old man couJd do about

it this time. A squad of state troop

ers was riding shotgun, shepherding

the weary marchers through the roll

ing farmland of Lowndes County,

notorious for its bloody past. The

only heckling had come from truck

ers over CB radios, with a few ob

scene gestures from passing pickups.

Tom Coieman, 72, hunched for

ward in a living room chair, leaning

close to the police scanner that

crackled with news of 70 demonstra

tors trekking along Highway 80 on

the final Selma-to-Montgomery leg

of a march to protest voting discrim

ination in the South.

It was 17 years after the Voting

Rights Act had been signed into law,

and the bedraggled marchers were

retracing the- steps of the historic

1965 march that left three civil

rights workers dl)ad and many

bklodied, but helped give birth to

the landmark legislation.

"There's no need for a march,"

said Coleman, a retired-state high

way engineer. "They got a four-to

one [black] majority in Lo\vndes

County now. Nobody's turned down

to vote any more."

The Voting Rights Act has

worked miracles In Lowndes County,

Ala., where Coleman h~ lived qui

etly ever since he stood trial for the

shooting of two civil rights workers

17 years ago jwt off the town

square. An all-white jury acquitted

him of charges that he killed Jona

than Daniels, 26, an Episcopal sem

inary student, and wounded a priest.

The trial took place in the same

courthou..<;e where three Ku Klux

Klansmen were acquitted of murder

ing Viola Liuzzo, a civil rights work

er and Detroit mother, just up the

road. The Klansmen were convicted

of her murder in federal court.

A week after Liuzzo's death, on

March 25, 1965, President Johnson ·

signed the Voting Rights Act into

law. At the time, Lowndes County

was 80 percent black, but had no

blacks on its jury rolls or in any

county office.

Now a black sh4'riff, John Hullett,

rides the back .roads. F'our out of five

county commissioners are black. So

are the tax assessor, tax collector,

sc~ board superintendent and

other officials.

"It was the last county in Alabama

to register blacks," Charles Smith,

the black county commissioner, rem

inisced. "Blacks couldn't use the

public schools they were taxed to

pay for. Now we have the key to the

schools and the jailhouse. In fact, the

jail is the most hospitable place in

Lowndes County."

But civil rights leaders say there

are places all across the South where

blacks are discouraged from flexing

their political muscle in 1982,

through tactics more subtle than

bullets. They point to Pickens Coun

ty, where Maggie Bozeman, 51, and

Julia Wilder, 69, were convicted of

illegally helping elderly blacks fill

out absentee ballots in a 1978 coun

ty election. An all-white jilly gave

the two black women what is be

lieved to be the stiffest sentences

ever handed down in an Alabama

voting fraud case.

The Rev. Joseph Lowery, presi

dent of the Atlanta-based Southern

Christian Leadership Conference,

organized this march to protest their

sentences, urge Gov. Fob James to

lean on the pardons and paroles

board to free them and urge Con

gress to extend the Voting Rights

Act. The marchers set out from

Pickens County Feb. 6, and are ex

pected to walk into Montgomery

Thursday for a rally at the Capitol.

The marchers have sparked none

of the violence that marked the 1965

voting registration march from Sel

ma, only the grumblings of ghosts

from that era. Any black who wants

to vote, says Coleman, "ought . to

know how to read .and write. Ought

to at least know who they're voting

for." Most blacks here don't hold

grudges ag8inst men like Tom .Cole

man.

"We're gonna let the good Lord

take care of him," said Frank Miles,

50, a black county commissioner.

"We've learned not to try to pay

back what they've done to us. We

don't have enough time."

To some old-timers, Coleman re-

Auto Dealers' Money

Adds Octane to Drive

Against FTC Regulation

By Paul Taylor

W:ll>hmgton Post Starr Wrili!r

As recently as eight years ago the

political action committee of the Na

tional Automobile Dealers Associa

tion was raising and doling out about

$40,000 per congressional election:

In the 1980 election it contributed

$1,034,875 ·to congressional candi

·dat.es, making it fourth-largest

among the nation's 2,901 PACs.

At least one reason for this Jack

and-the-beanstalk growth is a used

car regulation the Federal Trade

Commission adopted last year, and

which the NADA wants Congress to

kill.

The rule, adopted by the FTC /

after a five-year study of misrepre

sentations by used car dealers, wouJd

require a sticker listing "known de

fects" to be placed on all dealer-sold

used cars.

The dealers say such a require

ment would be the height of "bu

reaucratic arrogance," in the words

of Wendell Miller, president of their

19,000-member association.

Two years ago Congress voted it

self the power to scuttle FTC reg

ulations with the two-house veto.

NADA is now asking members to

make the used car rule the first test

of that procedure. Other industry

groups are watching closely to see if,

as many say they believe, legislators

will prove more sympathetic to busi

ness than to regulators.

PACs are one rea5on for this be

lief. NADA's 1980 campaign contri

butions of more than $1 million has

assured it at least an attentive hear

ing on Capitol Hill, where it claims

that the FTC's rule wouJd put a

crimp in the only part of the de

pressed car m~ket now keeping

many dealerships alive.

No one suggests that .the political

contributions, typically given in

chunks of $1,000 to $5,000, have

bought any votes, but a clear corre

lation exists between the dealers'

campaign giving and congressional

opposition to the FTC rule.

In the House, of 216 co-sponsors

of a veto resolution, 180, or 84 per

cent, reeeived c.ontributions in the

1980 campaign and the first six

months of 1981 from NADA.

Members of Congress who got

money from the NADA were three

times u likely to have co-sponsored

the resolution as those who got none,

according to flgUl'es compiled by

Congress W at.ch, the consumer ad

vocate group founded by Ralph

Nader.

The correlation is even more dis

tinct within the House Energy and

Commerce Committee, which ap

proved the veto resolution in Decem

ber. Of the 27 membl)rs ~bo sup-

ported the veto, 26 received a total

of $87,600 in campaign contributions

from NADA. Of the 14 who voted

no, six received a total of $8,350 in

NADA money.

. · A similar though less distinctive

pattern holds in the Senate, where a

veto resolution has 46 co-sponsors.

"This is one issue where I'm afraid

it looks like campaign contributions

just have had an impact," said Sen.

Slade Gorton (R-Wash.), one of a

group of llilpublicans in the Senate

op~ing the industry position.

Gorton, a former state attorney

general who often grappled with con

sumer complaints about used cars,

said he thinks the dealers lobby has

skillfully taken advantage of the ac

cess that comes with campaign con

tributions.

For its part, NADA prides itself

on its aggressiveness.

''We're not trying to influence pol

icy, we're trying to influence elec

tions," said Frank E. McCarthy,

NADA executive vice president. "We

just want to get the right objective

players here in Washington so our

grass-roots efforts can have an im

pact."

NADA is careful to aid both Dem

ocrats and Republicans, and that

policy has paid off. Despite their

general tilt toward the consumer side

of issues, Democrats, with the nota

ble exception of Rep. James J. Florio

(D-N.J.), have chosen not to make

much of an issue of the used car con

sumer protection bill.

In the Senate Commerce, Science

and Transportation Committee, all

eight Democratic members sup

ported the industry position in a 14-

to-4 vote in favor of the veto.

The ranking Democrat on that

committee is Wendell H. Ford of

Kentucky, who received $5,000 from

NADA and who, as chairman of the

Democratic Senatorial Campaign

Committee, is responsible for seeing

to it that his party's Senate cam

paigns are adequately funded.

Committee Chairman Bob Pack

wood (R-Ore.), who . heads the Na

tional Republican Senatorial Com

mittee, got $3,000 from NADA. But

he was a staunch opponent of the

veto resolution, and wed a parlia- ·

mentary device in December that

kept the issue from reaching the

floor. His strategy was designed to

give the consumer lobby some time

to build a head of steam.

The two lead spOnsors of the res

olution, Gary A. Lee (R-N.Y.) in the

House and Larry Pressler (R-S.D.)

in the Senate, have reintroduced

their veto resolutions, and say they

have detected no slackening of sup

port. Congress has 90 legislative days

to act.

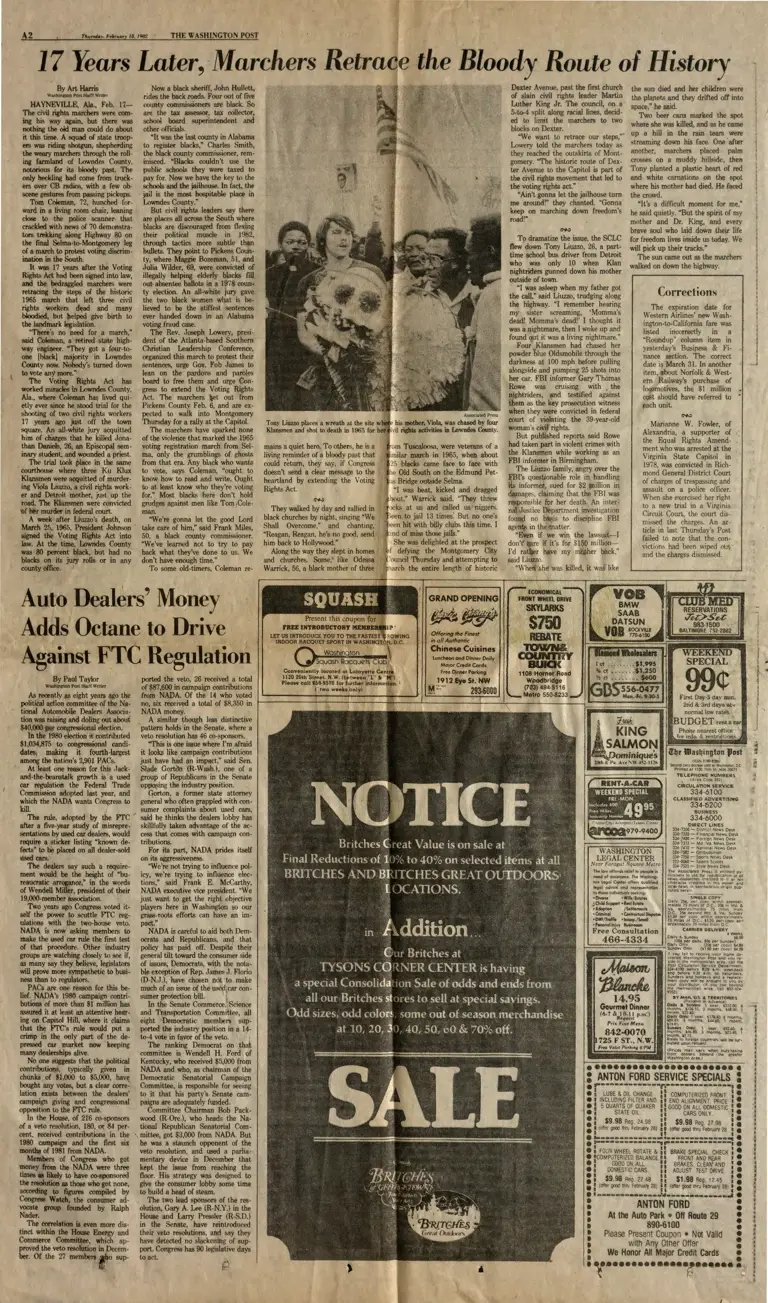

Tony Liuzzo places a wreath at the site

Klansmen and shot to death in 1965 for her

mains a quiet hero. To others, he is a

living reminder of a bloody past that

could return, they say, if Congress

doesn't send a clear message to the

heartland by extending the Voting

Rights Act.

c-#..:J

They walked by day and rallied in

black churches by night, singing "We

Shall Overcome," and chanting,

"Reagan, Reagan, he's no good, send

him back to Hollywood."

Along the way they slept in homes

and churches. Some, like Odessa

Warrick, 56, a black rnother of three

As.<ac1at.ed Press

his mother, Viola, was chased by four

rights activities in lAwndes Coonty.

Tuscaloosa, were veterans of a

Jar march in 1965, when about

blacks came face to face with

Old South on the Edmund Pet-

Bridge outside Sebna.

"I was beat, kicked and dragged

" Warrick said. "They threw

ocks at us and called us niggers.

en to jail 13 times: But no one's

een hit with billy clubs this time. I

.ind of miss those jails."

She was delighted at the prospect

f defying the Montgomery City

. ouncil Thursday and attempting to

h the entire length of h~storic

SQUASH ~~

~,s .. ·

GRAND OPENING

~~ Present th1s coupon for

FREE INTRODUCTORY MEMBER

LET US INTRODUCE YOU TO THE FASTEST ROWING

INDOOR RACQUET SPORT IN WASHJNGT .. -D.C.

Offering the Finest

in all Authentic

Chinese Cuisines

luncheon ond Dinner Doily

Major Credit Cords

free Dinner Parking

1912 Eye St.·NW

M~:·:-

Dexter Avenue, past the first church

of slain civil rights leader Martin

Luther King Jr. The council, on a

5-to-4 split along racial lines, decid

ed to limit the marchers to two

blocks on Dexter.

the sun died and her children were

the planets and they drifted off into

space," he said.

Two beer cans marked the spot

where she was killed, and as he came

up a hill in the rain tears were

streaming down his face_ One after

another, marchers placed palm

crosses on a muddy hillside, then

Tony planted a plastic heart of red

and white carnations on the spot

where his mother had died. He faced

the crowd.

"We want to retrace our steps,"

Lowery told the marchers today as

they reached the outskirts of Mont

gomery. "The historic route of Dex

ter Avenue to the Capitol is part of

the civil rights movement. that led to

the voting rights act."

"Ain't gonna let the jailhouse turn

me around!" they chanted. "Gonna

keep on marching down freedom's

road!"

"It's a difficult moment for me,"

he said quietly. uBut the spirit of my

mother and Dr. King, and evNy

brave soul who laid .down thei.r life

for freedom lives inside us today_ We

will pick up their tracks."

c-#..:J

To dramatize the issue, the SCLC

flew down Tony Liuzzo, 26, a part

time school bus driver from Detroit

who was only 10 when Klan

nightriders gunned down his mother

outside of town.

The sun came out as the marchers

walked on down the highway.

"I was asleep when my father got

the call," said Liuzzo, trudging along

the highway. "I .remember hearing

my sister screaming, 'Momma's

dead! Momma's dead!' I thought it

was a nightmare, then I woke up and

found out it was a living nightmare,"

Corrections

The expiration date for

Western Airlines' new Wash

ington-to-California fare was

listed incorrectly in a

"Roundup" column item in

yesterday's Business & Fi

nance section. The correct

date is March 31. In another

item, about Norfolk & West

ern .Railway's purchase of

locomotives, the $1 million

cost should have referred to •

each unit.

Four Klansmen had chased her

powder blue Oldsmobile through the

darkness at 100 mph before pulling

alongside and pumping 25 shots into

her car. ·FBI informer Gary Thomas ·

Rowe was cruising with . the

nightriders, and testified against

them as the key prosecution witness

when they were convicted in federal

court of violating the 39-year-old

woman's civil rights.

c-#..:J

Marianne W. Fowler, of

Alexandria, a supporter of

the Equal Rights Amend

ment who was arrested at the

Virginia State Capitol in

1978, was convicted in Rich

mond General District Court

of charges of trespassing and

assault on a police officer.

When she exercised her right

to a new trial in a Virginia

Circuit Court, the court dis

missed the charges. An ar

ticle in last Thursday's Post

failed to note that the con

victions had been wiped out

and the charges dismissed .

But published reports said Rowe

had taken part in violent crimes with

the Klansmen while working as an

FBI informer in Birmingham.

The Liuzzo family, angry over the

FBI's questionable role in handling

its informer, sued for $2 million in

damages, claiming that the FBI was

responsible for her death. An inter

nal Justice Department investigation

found no basis to discipline FBI

agents in the matter.

"Even if we win the lawsuit- !

don't care if it's for $150 million

l'd rather have my mother back,"

said Liuzzo.

"When she was killed, it was like

ECONOMICAL

FRONT WHEEL ORIVE

SKYlARKS

$750

REBATE

~

BUICK

11081Ho.n:ter Road

Wooabrldge

(703) 494·5116

Metro 550·8233

SPECIAL

99¢··

First Day-3 day mm.

2nd & 3rd days at

normal low rates.

! _~G

~~~~?u~ m~r RJas~ington Post

20th & Pa. A" l'oiW 4S2-11 26 HSSN 0190·87861

~;:~~~~~~~~ Secono c1a1s oostaoe oaid 11 Na~n~~010t1, OC. Printed at 11SO 15th St. NW 20071

TELEPHONE NUMBE RS

(Area Code 202)

CIRCUL A'T10N SERVICE

334-6100

CLASSIFIE D ADVE RT ISING

334-6200

BUSIN E SS

334-6000

DIRECT LIN ES

334-7300 - D"lricl News Desk

334-7320- Financ•al News Desk

334-7400- Foreion News Desk

334-7313- Md./Va News Desk

WASHINGT ON ii::;~: ~~~~:i~:;s Des<

LEGAL CENTER ~~~:~g~: ~:;:~ ~~o~!sDesk

Near Faragut Square Metro 334-7535- Slvle ~ews Desk

The law affords relief to people in The Associated Pres.s Is. enhtled ex~

need of assistance. The Washing · ~~~~~~~rs~~~~:s'o;,~~~~~~~~:f"o~'~':

ton leQol Center affen qualified otnerw•se cred•ted 1n lh•s paper and

legal odv;ce and representation local news of spontaneous origin Pub·

to those individuals seeking: hshed hcre_in_. __ _

• Divot<t • Wills/EslaiOi $INGLE COPY

;-Child Suppcwt • Real &tate ~:i:;,/r!• m~~s ~~PC') C.' 1~ i~~~-x~

• Adoption / Settlements Va. approximatelv 7S miles from

• Criminal • Controd\lal Disputes ~~~ ~ ~~~"~[;i,~n ~P~~Ox~~~~!1~

•OWl/Traffic •lncorp./Smolf 75 miles of DC.; Sl.25 per .copv aP-

' PtrSOnallnjuy Butineues proxlmatelv 75 miles from 0 C.

Free Consultation cARRIER oeLtVE RY4 W<eks

466-4334 °01\';~ ~~~"a'itv, SO. oer Sundavl

8 00

~IP.!!!!~!!!!!!~~~· oa•tv on1v <20¢ orr co;)vJ u eo Sundey Only (Sl 00 oer coov) u 00

If vou fa1l to receive vour home de-

livered Washington Post and vou re·

side in the metrooofllan area , call the r,.J • ..,.. ' Post C•rculalion Service Det:~artment ,

1Mt8f.JIU 334· 6100 before 8:30 a m. wcekd~vs

" ~~~d~~o~~d9~1id1a~· a~d :~~~~~:;:~

. , ' ment COPY w•ll be brought to vou bv

vour distributor (If vo1.1 live bevond

~~~)etrOQOii,an area , call 800-11241·

14.95 IIY MAIL U.S. & TERRITORIES

CPava ble m Advance)

Gourmet Dinner ~~hs~ ~~~~s~= 31 ,;:::,~,. '~~~·-~: ~

(6.7 •\~~~!.~ fl . m~ ) ~~ho:J;;~·vur, $178.40, 6 month>,

Prix f ixe M•!lu m·~~; l monlh$, w 60. 1 month,

· Sunday Ontv: 1 vear. <93 60 6 842-0070 month>. S46.80, 3 months, m 40, 1

month, S7.75

725 F ST., N·. W. ~~~~~~ ~~~~e::~u;~~ntrles w ilt be fur ..

Frtt Vol" Por~tnt 6 PM IPricu mav varv when PurchaSing

from dealers be\lond fhe greater

Washln~uon area.)

••••••••••••••••••••••••

: ANTON FORO SERVICE SPECIALS :

.~----·--------r~-------------·•

e : LUBE & OIL CHANGE :: COMPUTERIZED FRONT : e

e I INCLUDING FILTER AND 11 ENO ALIGNMENT PRICE I e

e : 5 QUARTS OF QUAKER I: GOOD ON ALL DOMESTIC I e

e 1 STATE OIL . :1 CARS ONLY : •

: : $9.98 Reg. 24.98 :: $9.98 Reg. 27 98 : :

• I (oNer good 1hru February 28) 11 (offer good lhru Fellrwry 28 1 e

I II I . .._ _____________ ·-------------.. ·• ...... ------------. .------------,..-, .

e : FOUR WHEEL ROTATE & :: BRAKE SPECIAL CHECK : •

e : cOMPUTERIZED BALANCE. II FRONT AND REAR I e

e 1 GOOD ON ALL 11 BRAKES, CLEAN' AND 1 •

e 1 DOMESTIC CARS :: ADJUST. TEST DRIVE : •

:: $9.98 Reg 22 48 :: $1 .98 Reg 12 45 ::

• I (offer good 1hru February 28) II (offer good 1hru February 281 I e

I I I I

··-------------J~-------------~. : ANTON FORO :

: At the Auto Park • OH Route 29 :

• 890-6100 •

: Please Present Coupon • Not Valid :

1 with Any Other Offer •

: We Honor All Major Credit Cards :

'\··············~······· l •

I -

I'

I

I

' l

I

' ! !

1 • • I

I

..

l

i

I

I

1 •

•

' t r

I

I

I

t

l

J

..

"'

~ -

It

~

..

• i

:

I

I

~ • • • ..

' •

= • • • • .;

;

• I

•

i

I • i

I

• ~

• ' w

:

I

)

.