Appellants' Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

July 6, 1998

238 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Appellants' Jurisdictional Statement, 1998. 6e426e34-d90e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79bbd8b2-6c24-4112-b76b-22332caf251c/appellants-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Ny - . . y =

2 Ne aii » a “¥ 3 VE 3 > I — ] vee Sy RTE ge ; TENT DW OY YT TN I TR

M J wo

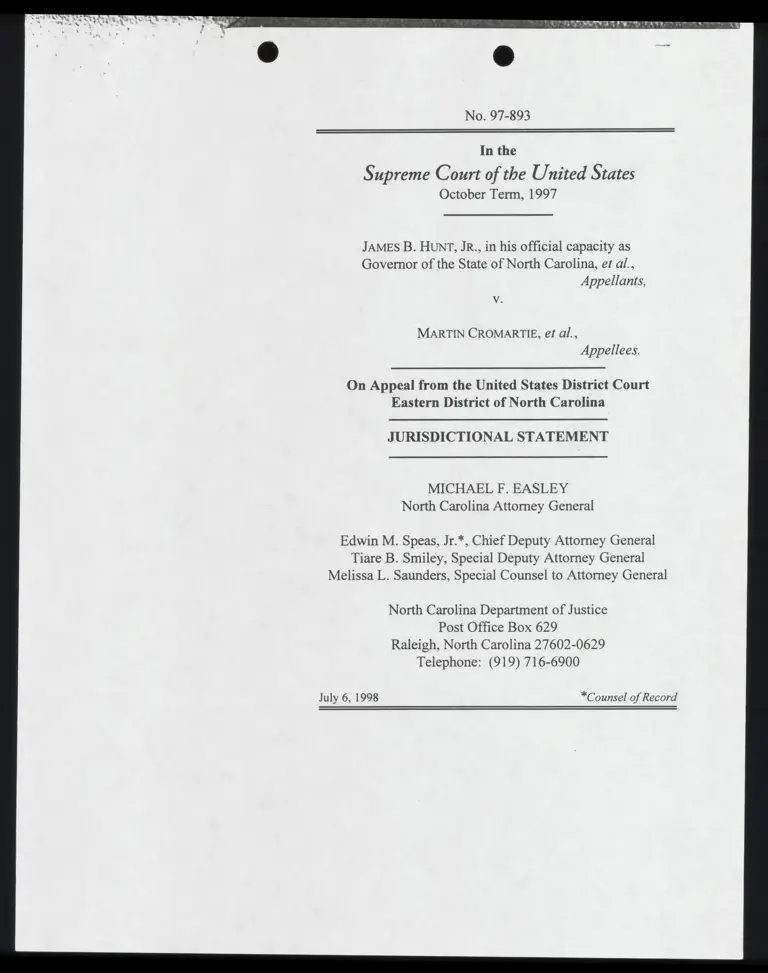

No. 97-893

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

North Carolina Attorney General

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.*, Chief Deputy Attorney General

Tiare B. Smiley, Special Deputy Attorney General

Melissa L. Saunders, Special Counsel to Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602-0629

Telephone: (919) 716-6900

July 6, 1998 *Counsel of Record

¥

f

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. In a racial gerrymandering case, is an inference drawn from

the challenged district’s shape and racial demographics,

standing alone, sufficient to support summary judgment for

the plaintiffs on the contested issue of the predominance of

racial motives in the district’s design, when it is directly

contradicted by the affidavits of the legislators who drew the

district?

2. Does a final judgment from a court of competent jurisdiction,

which finds a state’s proposed congressional redistricting

plan does not violate the constitutional rights of the named

plaintiffs and authorizes the state to proceed with elections

under it, preclude a later constitutional challenge to the same

plan in a separate action brought by those plaintiffs and their

privies?

3. Is a state congressional district subject to strict scrutiny under

the Equal Protection Clause simply because it is slightly

irregular in shape and contains a higher concentration of

minority voters than its neighbors, when it is not a majority-

minority district, it complies with all of the race neutral

districting criteria the state purported to be following in

designing the plan, and there is no direct evidence that race

was the predominant factor in its design?

This page intentionally left blank.

iii

LIST OF PARTIES

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as Governor of the

State of North Carolina, DENNIS WICKER in his official capacity

as Lieutenant Governor of the State of North Carolina, HAROLD

BRUBAKER in his official capacity as Speaker of the North Carolina

House of Representatives, ELAINE MARSHALL in her official

capacity as Secretary of the State of North Carolina, and LARRY

LEAKE, S. KATHERINE BURNETTE, FAIGER BLACKWELL,

DOROTHY PRESSER and JUNE YOUNGBLOOQOD in their capacity

as the North Carolina State Board of Elections, are appellants in this

case and were defendants below;

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE, R. O.

EVERETT, J. H. FROELICH, JAMES RONALD LINVILLE,

SUSAN HARDAWAY, ROBERT WEAVER and JOEL K.

BOURNE are appellees in this case and were plaintiffs below.

1v

This page intentionally left blank.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED... 5. oitsainy dahe ts vassiviinins i

LISTOF PARTIES mo i. coos sis pidgin s 4's 24a ii

TABLEOF AUTHORITIES ......... 0... si vii

OPINIONS BELOW .. ovo vi cnissninanan ns sn sin 1

JURISDICTHON citi cdi bens vi ts Paro aays bal 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED .....i i... caniinainns 2

STATEMENTOFTHE CASE ........ 00 a0. caidas 2

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTINGPROCESS. ........cr0iiu 2

B.. THETI9TPLAN. oo. hs viviviniscs sas sails o vivian yon 3

C. LEGAL CHALLENGES TO THE 1997 PLAN. ............ 6

1. The Remedial Proceedings in Shaw. ............ 6

2. The Parallel Cromartie Litigation .............. 8

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION . ...... 9

E. THEIOOSINTERIMPLAN. .. ...... ioscan ninninns 11

vi

ARGUMENT . ode. oii oid Anis i Pe ss 12

1. SUMMARY JUDGMENT ISSUE...............%. 12

NH: PRECLUSIONISSUE. .... cin. vaenise eave nns 16

Hi. PREDOMINANCE ISSUE. “.. viv vivic evs vinvies sinks 20

CONCLUSION... ...... 000 fied unails widein does 30

Vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Ahng v. Allsteel, Inc., 96 F.3d 1033 (7th Cir. 1996) ......... 17

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242

(1986) ........ooiviiiiiiiiii 13,14,15,16

Bushy. Vera, S17 U.8.952(1996) ........ ven. vy passim

Celotex Corp. v. Catrent, 477 U.8. 317(1986) ............. 13

Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A. v. Celotex Corp.,

S6F.3d343QdCir. 1995)... 0. ci ae 17

Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U.S. 351 (1876) ............ 18

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1987) ............ 14,16

Federated Dep't Stores, Inc. v. Moitie,

452 U.S. 304 (F081). Tv. oi. Je sincnr cnn vena 18,19

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735(1973) ............... v4

Gonzalez v. Banco Cent. Corp., 27 F.3d 751

CIstCI. JO0Y ov oh as a ae a 17

Hlinoisy. Krull, 480 U.S. 340 (1987) ......ccocuvi inne vns 12

Jaffree v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461 (11th Cir. 1988) ......... 17

Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529 (1995) ........... 15

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725(1983) ........ huevos 22

Lawyer v. Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186 (1997) ...... 21,24,25,27,28

viii

McDonald v. Board of Election Commr’s of Chicago,

3940S. 802¢1089) ....... a. A a Aaa 12

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995) .............. passim

Mueller v. Allen, 463. U.S. 3881983) ....... cco vunnnnn 12

Nordhorn v. Ladish Co., 9 F.3d 1402 (9th Cir. 1993) ....... 17

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) ...... 14,28

Quilter v. Voinovich, 981 F. Supp. 1032

(N.D. Ohio 1997), affd, 118 S. Ct. 1358

CTOOBY: oie 0 Pte carom wun v0 a 24,25,26,27,28

Reynolds. Sims, 377U.8.533 (1964) .............. 5+. 22

Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S.57(1981) ..........c0nuu. 12

Royal Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L Capital Corp.,

960.F.2d 1286 (5th Cir, 1992)%. . ou ve viii 17

Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899(1996) .............. 2,15,21,26

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) ......... 3,15,20,24,25,28

Starceski v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 54 F.3d 1089

ACI, 1995) he i Ted wr aos Buns eh is 14

United States v. Hays, S15 U.S. 737(1995) .............. 4 !

Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146 (1993) ................ 25

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.8.535(1978) ........ 00.004, 25

1X

STATUTES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

BUS. C BI28 tii rai at aE A NO

BUS.C. 82284)... oh oat em 19

1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, ch. 2.8 1.1 <a, coca coi aiia 11

18 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE’S FEDERAL

PRACTICE § 131.40[3][e][I][B] (3d ed. 1997) ...... .. 19

18 C. WRIGHT, ET AL., FEDERAL PRACTICE AND

PROCEDURE 84457 (1981) «vcs... vat ln 19

This page intentionally left blank.

No. 97-893

In the

S upreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1997

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as

Governor of the State of North Carolina, ef al.,

Appellants,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Governor James B. Hunt, Jr., and the other state defendants below

appeal from the final judgment of the three-judge United States

District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, dated April

6, 1998, which held that the congressional redistricting plan enacted

by the North Carolina General Assembly on March 31, 1997, was

unconstitutional and permanently enjoined appellants from

conducting any elections under that plan.

OPINIONS BELOW

The April 14, 1998, opinion of the three-judge district court,

which has not yet been reported, appears in the Appendix to this

jurisdictional statement at 1a.

2

JURISDICTION

The district court’s judgment was entered on April 6, 1998. On

April 8, 1998, appellants filed an amended notice of appeal to this

Court. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §

1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, Summary Judgment. See App. 169a & 171a-173a.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTING PROCESS.

In Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (Shaw II), this Court held

that District 12 in North Carolina’s 1992 congressional redistricting

plan (“the 1992 plan”) violated the Equal Protection Clause because

race predominated in its design and it could not survive strict scrutiny.

On remand, the district court afforded the state legislature an

opportunity to redraw the State’s congressional plan to correct the

constitutional defects found by this Court, and the legislature

established Senate and House redistricting committees to carry out

this task.

In consultation with the legislative leadership, the committees

determined that, to pass both the Democratic-controlled Senate and

the Republican-controlled House, the new plan would have to

maintain the existing partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegation (a six-six split between Democrats and Republicans).

Toward that end, the committees sought a plan that would preserve

the partisan cores of the existing districts and avoid pitting

incumbents against each other, to the extent consistent with the goal

of curing the constitutional defects in the old plan. To craft

“Democratic” and “Republican” districts, the committees used the

results from a series of elections between 1988 and 1996.

In designing the plan, the committees of course sought to comply

with the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, as well as the

constitutional requirement of population equality. Acutely conscious

of their responsibilities under Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993)

(“Shaw I’), and its progeny, however, they sought a plan in which

racial considerations did not predominate over traditional race-neutral

districting criteria. Toward this end, they decided to emphasize the

following traditional race-neutral districting principles in designing

the plan: (1) avoid dividing precincts; (2) avoid dividing counties

when reasonably possible; (3) eliminate “cross-overs,” “double cross-

overs,” and other artificial means of maintaining contiguity; (4) group

together citizens with similar needs and interests; and (5) ensure ease

of communication between voters and their representatives. The

committees did not select geographic compactness as a factor that

should receive independent emphasis in constructing the plan.

The committees’ strategy proved successful. On March 31, 1997,

the North Carolina legislature enacted a new congressional

redistricting plan, 1997 Session Laws, Chapter 11 (“the 1997 plan”),

the redistricting law at issue in this case. The plan is a bipartisan one,

endorsed by the leadership of both parties in both houses.

B. THE 1997 PLAN.

The 1997 plan creates six “Democratic” districts and six

“Republican” districts. The new districts are designed to preserve the

partisan cores of their 1992 predecessors, yet their lines are

significantly different: they reassign more than 25% of the State’s

! In North Carolina, as in most of the southeastern states, it is virtually impossible

to design a congressional map that does not split any of the State’s 100 counties,

given the constitutional mandate of population equality and other legitimate

districting concerns.

4

population and nearly 25% of its geographic area. The most dramatic

changes are in District 12, which contains less than 70% of its

original population and only 41.6% of its original geographic area.

The 1997 plan respects the traditional race-neutral districting

criteria identified by the legislature: it divides only two of the State’s

2,217 election precincts (and then only to accommodate peculiar local

characteristics); it divides only 22 of the State’s 100 counties (none

among more than two districts); all of its districts are contiguous, and

it does not rely on artificial devices like cross-overs and double cross-

overs to achieve that contiguity.? Though the legislature did not

emphasize geographic compactness for its own sake in designing the

1997 plan, its districts are significantly more geographically compact,

judged by standard mathematical measures of geographic

compactness, than their predecessors in the 1992 plan.

The 1997 plan is racially fair, but race for its own sake was not

the predominant factor in its design or the design of any district

within it. Indeed, 12 of the 17 African-American members of the

House voted against the plan because they believed it did not

adequately take into account the interests of the State’s African-

American residents.

District 12 is one of the six “Democratic” districts established by

the 1997 plan. Seventy-five percent of the district’s registered voters

are Democrats, and at least 62% of them voted for the Democratic

candidate in the 1988 Court of Appeals election, the 1988 Lieutenant

Governor election, and the 1990 United States Senate election.

District 12 is not a majority-minority district by any measure: only

46.67% of its total population, 43.36% of its voting age population,

2 In contrast, the 1992 plan this Court invalidated in Shaw II divided 80 precincts;

divided 44 of the State’s 100 counties (seven of them among three different

districts); and achieved contiguity only through artificial devices.

5

and 46% of its registered voter population is African-American.’

While it does rely on the strong demonstrated support of African-

American voters for Democratic candidates to cement its status as one

of the six Democratic districts, partisan election data, not race, was

the predominant basis for assigning those voters to the district.

District 12 respects the traditional race-neutral redistricting

criteria identified by the legislature. It divides only one precinct (a

precinct that is divided in all local districting plans as well); it

includes parts of only six counties; and it achieves contiguity without

relying on artificial devices like cross-overs and double cross-overs.*

It creates a community of voters defined by shared interests other than

race, joining together citizens with similar needs and interests in the

urban and industrialized areas around the interstate highways that

connect Charlotte and the Piedmont Urban Triad. Of the 12 districts

in the 1997 plan, it has the third shortest travel time (1.67 hours) and

the third shortest distance (95 miles) between its farthest points,

making it highly accessible for a congressional representative. District

12 is significantly more geographically compact than its 1992

predecessor.

District 1 is another of the six “Democratic” districts established

by the 1997 plan. Unlike District 12, District 1 is a majority-minority

district by one measure: 50.27% of its total population is African-

American. Like District 12, District 1 respects the traditional race-

neutral redistricting criteria identified by the legislature. It contains no

divided precincts; it divides only 10 counties; and it achieves

contiguity without relying on artificial devices like cross-overs and

’ In contrast, 56.63% of the total population, 53.34% of the voting age

population, and 53.54% of the registered voter population of District 12 in the 1992

plan was African-American.

* In contrast, District 12 in the 1992 plan divided 48 precincts; included parts of

ten counties; and achieved contiguity only through artificial devices.

6

double cross-overs.’ It creates a community of voters defined by

shared interests other than race, joining together citizens with similar

needs and interests in the mostly rural and economically depressed

counties in the State’s northern and central Coastal Plain.

Because 40 of North Carolina’s 100 counties are subject to the

preclearance requirements of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the

legislature submitted the 1997 plan to the United States Department

of Justice for preclearance. The Department precleared the plan on

June 9, 1997.

C. LEGAL CHALLENGES TO THE 1997 PLAN.

1. The Remedial Proceedings in Shaw.

Equal protection challenges to the 1997 plan were first raised in

the remedial phase of the Shaw litigation, when the State submitted

the plan to the three-judge court to determine whether it cured the

constitutional defects in the earlier plan. Two of the plaintiffs who

challenge the 1997 plan in the instant case -- Martin Cromartie and

Thomas Chandler Muse -- participated as parties plaintiff in that

remedial proceeding, represented by the same attorney who represents

them in this case, Robinson Everett.

In that proceeding, Cromartie, Muse, and their co-plaintiffs (“the

Shaw plaintiffs”) were given an opportunity to litigate any

constitutional challenges they might have to the 1997 plan, a plan

which the State had enacted under the Shaw court’s injunction, as a

5 In contrast, District 1 in the 1992 plan split 25 precincts and 20 counties, and

achieved contiguity only through artificial devices.

® The original plaintiffs in Shaw were five residents of District 12 as it existed

under the 1992 plan. On remand from this Court’s decision in Shaw II, Cromartie

and Muse sought and obtained the district court's leave to join them as plaintiffs, in

order to assert a claim that District 1 in the 1992 plan was an unconstitutional racial

gerrymander -- a claim which this Court had just held that the original Shaw

plaintiffs lacked standing to assert.

proposed remedy for the plan this Court had just declared

unconstitutional.” They elected not to avail themselves of that

opportunity. They did inform the Shaw court that they believed the

1997 plan to be “unconstitutional” because Districts 1 and 12 -- the

same districts they now challenge in this action -- had been “racially

gerrymandered.” App. 183a-186a. At the same time, however, they

asked the court not to decide their constitutional challenges to the

proposed remedial plan. The reason they gave was somewhat curious:

that the court lacked authority to entertain these claims, because none

of them had standing to challenge the proposed plan under United

States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (1995).} For this reason, they asked the

court “not [to] approve or otherwise rule on the validity of” the new

plan, and to “dismiss this action without prejudice to the right of any

person having standing to maintain a separate action attacking [its]

constitutionality.” App. 186a. The state defendants actively opposed

plaintiffs’ effort to reserve their constitutional challenges to the 1997

plan for a new lawsuit.

The three-judge court rejected the Shaw plaintiffs’ argument that

it lacked jurisdiction to entertain their constitutional challenges to the

State’s proposed remedial plan. App. 166a-168a. The court then went

7 App. 181a-182a (directing the Shaw plaintiffs to advise the court “whether they

intend[ed] to claim that the [1997] plan should not be approved by the court because

it does not cure the constitutional defects in the former plan” and, if so, “to identify

the basis for that claim”).

* App. 186a (“Because of the lack of standing of the Plaintiffs, there appears to

be no matter at issue before this Court with respect to the new redistricting plan”).

The Shaw plaintiffs based this argument on the assertion that none of them resided

in the redrawn District 12. App. 185a-186a. The argument was somewhat

disingenuous, for at least two of their number -- Cromartie and Muse -- resided in

the redrawn District 1 and thus had standing to assert a racial gerrymandering

challenge to the 1997 plan, even under their own bizarre reading of the Hays

decision.

8

on to rule that the plan was “in conformity with constitutional

requirements” and that it was an adequate remedy for the

constitutional defects in the prior plan “as to the plaintiffs and

plaintiff-intervenors in this case.” App. 160a, 167a. On that basis, the

court entered an order approving the plan and authorizing the state

defendants to proceed with congressional elections under it. App.

157a-158a. The Shaw plaintiffs took no appeal from that order.

2. The Parallel Cromartie Litigation.

Having forgone an opportunity to litigate their constitutional

challenges to Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997 plan before the three-

judge court in Shaw, Cromartie and Muse immediately sought to have

those same claims adjudicated by a different three-judge court. They

did so by amending a complaint in a separate lawsuit they had

previously filed against the same defendants, a lawsuit in which they

were also being represented by Robinson Everett. In that amended

complaint, Cromartie, Muse, and four persons who had not been

named as plaintiffs in Shaw (“the Cromartie plaintiffs”) asserted

racial gerrymandering challenges to Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997

plan, the very plan the three-judge court in Shaw had just approved

over their objection.

On January 15, 1998, the Cromartie case was assigned to a three-

judge panel, consisting of one judge who had served on the three-

judge panel in Shaw -- Judge Voorhees, who had dissented from the

panel’s decisions in Shaw I and Shaw II -- and two new judges. On

January 30, 1998, the Cromartie plaintiffs moved for a preliminary

injunction halting all further elections under the 1997 plan. Several

days later, they also moved for summary judgment. The state

defendants responded with a cross-motion for summary judgment.

On March 31, 1998, before it had permitted either party to

conduct any discovery, the three-judge court heard brief oral

arguments on the pending motions for preliminary injunction and

summary judgment. Three days later, the court, with Circuit Judge

9

Sam J. Ervin, 111, dissenting, entered an order granting the Cromartie

plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment, declaring District 12 in the

1997 plan unconstitutional, and permanently enjoining the state

defendants from conducting any elections under the 1997 plan.’ The

court’s order did not explain the basis for its decision, stating only

that “[mJ]emoranda with reference to [the] order will be issued as soon

as possible.” App. 45a-46a.

The state defendants immediately noticed an appeal to this Court.

Since the elections process under the 1997 plan was already in {ull

swing, they asked the district court to stay its April 3rd order pending

disposition of that appeal. The district court declined to do so. The

state defendants then applied to Chief Justice Rehnquist for a stay of

the same order. The Chief Justice referred that application to the full

Court, which denied it on April 13, 1998, with Justices Stevens,

Ginsburg, and Breyer dissenting. When this Court acted on that stay

application, the district court had yet to issue an opinion explaining

the order and permanent injunction in question.

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION.

On April 14, 1998, the three-judge court issued an opinion

explaining the basis for its order of April 3, 1998. At the outset, the

court ruled that “the September 12, 1997, decision of the Shaw three-

judge panel was not preclusive of the instant cause of action, as the

panel was not presented with a continuing challenge to the

redistricting plan.” App. 3a-4a. The court then held that the

Cromartie plaintiffs were entitled to summary judgment on their

challenge to District 12, because the “uncontroverted material facts”

9

The order made no reference to District 1, though the Cromartie plaintiffs also

had moved for summary judgment on their claim that it was an unconstitutional

racial gerrymander. Not until the memorandum opinion was filed on April 14, 1998,

did the court explain that it was denying summary judgment as to District 1. App.

22a-23a, 53a.

10

established that the legislature had “utilized race as the predominant

factor in drawing the District.” App. 21a-22a. Unlike the lower courts

whose “predominance” findings this Court upheld in Miller, Bush,

and Shaw 11, the court did not base this finding on any direct evidence

of legislative motivation; instead, it relied wholly on an inference it

drew from the district’s shape and racial demographics. The court

reasoned that District 12 was “unusually shaped,” that it was “still the

most geographically scattered” of the State’s congressional districts,

that its dispersion and perimeter compactness measures were lower

than the mean for the 12 districts in the plan, that it “include[s] nearly

all of the precincts with African-American population proportions of

over forty percent which lie between Charlotte and Greensboro,” and

that when it splits cities and counties, it does so “along racial lines.”

The court concluded that these “facts,” which it characterized as

“uncontroverted,” established -- as a matter of law -- that the

legislature had “disregarded traditional districting criteria” and

“utilized race as the predominant factor” in designing District 12.

App. 19a-22a.

Finally, the court held that the Cromartie plaintiffs were not

entitled to summary judgment on their challenge to District 1, the

only majority-minority district in the 1997 plan. The court did not

explain the basis for this holding, except to say that the Cromartie

plaintiffs had “failed to establish that there are no contested material

issues of fact that would entitle [them] to judgment as a matter of law

as to District 1.” App. 22a. In denying the state defendants’ cross-

motion for summary judgment on the same claim, however, the court

stated that the “contested material issue of fact” concerned “the use

of race as the predominant factor in the districting of District 1.” App.

23a.

Judge Ervin dissented. App. 25a. In his view, the majority’s

conclusion that the evidence in the summary judgment record was

sufficient to establish -- as a matter of law -- that race had been the

predominant factor in the design of District 12, was strikingly

11

inconsistent with its conclusion that the same evidence was not

sufficient to establish that race had been the predominant factor in the

design of District 1, given that the two districts were drawn by the

same legislators, at the same time, as part of the same state-wide

redistricting process. The inconsistency was even more striking, he

noted, “when one considers that the legislature placed more African-

Americans in District 1 . . . than in District 12.” App. 38a.

E. THE 1998 INTERIM PLAN.

On April 21, 1998, the court entered an order allowing the

General Assembly 30 days to redraw the State’s congressional

redistricting plan to correct the defects it had found in the 1997 plan.

App. 55a. On May 21, 1998, the General Assembly by bipartisan

vote enacted another congressional redistricting plan, 1998 Session

Laws, Chapter 2 (“the 1998 plan”), and submitted it to the court for

approval. The 1998 plan is effective for the 1998 and 2000 elections

unless this Court reverses the district court decision holding the 1997

plan unconstitutional." The Department of Justice precleared the

1998 plan on June 8, 1998.

On June 22, 1998, the district court entered an order tentatively

approving the 1998 plan and authorizing the State to proceed with the

1998 elections under it. App. 175a-180a. The court explained that

the plan’s revisions to District 12 “successfully addressed” the

concerns the court had identified in its April 14, 1998 opinion, and

that it appeared, “from the record now before [the court],” that race

had not been the predominant factor in the design of that revised

district. The court noted that it was not ruling on the constitutionality

of revised District 1, and it directed the parties to prepare for trial on

1 See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, ch. 2, § 1.1 (“The plan adopted by this act is effective

for the elections for the years 1998 and 2000 unless the United States Supreme

Court reverses the decision holding unconstitutional G.S. 163-201(a) as it existed

prior to the enactment of this act.”).

12

that issue. It also “reserve[d] jurisdiction” to reconsider its ruling on

the constitutionality of redrawn District 12 “should new evidence

emerge.” App. 177a-179a.

ARGUMENT

I. SUMMARY JUDGMENT ISSUE.

The district court’s application of the Rule 56 summary judgment

standard in this context presents substantial questions that warrant

either plenary consideration or summary reversal.

The threshold inquiry for deciding whether a district is subject to

strict scrutiny under Shaw, turning as it does on the actual motivations

of the state legislators who designed and enacted the plan, is

peculiarly inappropriate for resolution on summary judgment. This

Court has repeatedly affirmed its “reluctance to attribute

unconstitutional motives to the states.” Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S.

388, 394 (1983). When a federal court is called upon to judge the

constitutionality of an act of a state legislature, it must “presume” that

the legislature “act[ed] in a constitutional manner,” Illinois v. Krull,

480 U.S. 340, 351 (1987); see McDonald v. Board of Election

Comm rs of Chicago, 394 U.S. 802, 809 (1969), and remember that

it “is not exercising a primary judgment but is sitting in judgment

upon those who also have taken the oath to observe the Constitution.”

Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57, 64 (1981) (internal quotation

omitted). In Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995), this Court made

clear that these cautionary principles are fully applicable in Shaw

cases. See 515 U.S. at 915 (“Although race-based decisionmaking is

inherently suspect, until a claimant makes a showing sufficient to

support that allegation, the good faith of a state legislature must be

presumed.”) (citations omitted). Indeed, they have even greater force

in Shaw cases, given the sensitive and highly political nature of the

redistricting process and the “serious intrusion” on state sovereignty

that federal court review of state districting legislation represents. 515

13

U.S. at 916 (admonishing lower courts to exercise “extraordinary

caution” in adjudicating Shaw claims) (emphasis added).

Ignoring this Court’s directives, and oblivious to the fact that the

invalidation of a sovereign state’s duly-enacted electoral districting

plan is not a casual matter, the court below resolved the contested

issue of racial motivation -- and with it, the issue of the plan’s validity

-- on summary judgment. On the basis of a brief hearing, at which it

heard no live evidence but merely argument from counsel, it

concluded that plaintiffs had established -- as a matter of law -- that

race had been the predominant factor in the construction of District

12. App. 21a-22a. In so doing, it committed clear and manifest error.

The district court’s decision is flatly inconsistent with this Court’s

decision in Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986).

There, this Court made clear that a motion for summary judgment

must be resolved by reference to the evidentiary burdens that would

apply at trial. Id. at 250-54. Where, as here, the party who seeks

summary judgment will have the burden of persuasion at trial, he can

obtain summary judgment only by showing that the evidence in the

summary judgment record is such that no reasonable factfinder

hearing that evidence at trial could possibly fail to find for him. /d. at

252-55. In other words, he must demonstrate that the evidence,

viewed in the light most favorable to his opponent, is “so one-sided”

that he would be entitled to judgment as a matter of law at trial. /d. at

249-52.

In this case, plaintiffs had the burden of persuasion at trial on the

predominance issue. Miller, 515 U.S. at 916. The district court utterly

ignored this critical fact in concluding that they were entitled to

summary judgment on their claim challenging the constitutionality of

District 12. Indeed, the court appeared to be analyzing their motion

for summary judgment under the standard that applies to parties who

will not have the burden of persuasion at trial. App. 21a (citing

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 324 (1986)).

14

Had the district court applied the standard this Court’s precedents

direct it to apply, it could not have justified the conclusion that

plaintiffs were entitled to summary judgment on their claim

challenging the constitutionality of District 12. To obtain summary

judgment on that claim under Liberty Lobby, plaintiffs were required

to show that no reasonable finder of fact, viewing the evidence in the

summary judgment record in the light most favorable to the state

defendants, could possibly find that race had nor been the

predominant factor in its design. 477 U.S. at 252-55. The only

evidence in the record tending to show that race had been the

predominant motivation in the construction of District 12 was an

inference the plaintiffs asked the court to draw from their evidence of

the district’s shape and racial demographics.'' There was absolutely

no direct evidence? of such an improper motivation before the district

court: no concessions to that effect from the state defendants, and no

evidence of statements to that effect in the legislation itself, the

committee hearings, the committee reports, the floor debates, the

State’s § 5 submissions, or the post-enactment statements of those

who participated in the drafting or enactment of the plan. Compare

''' Plaintiffs presented various maps and demographic data as well as the affidavits

of several experts who relied on the same evidence of shape and racial demographics

to opine that race was the predominant factor used by the State to draw the

boundaries of the congressional districts. Such postenactment testimony of outside

experts “is of little use” in determining the legislature’s purpose in enacting a

particular statute, when none of those experts “participated in or contributed to the

enactment of the law or its implementation.” Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578,

595-96 (1987).

12 While the distinction between “direct” and “circumstantial” evidence is “often

subtle and difficult,” Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 291 (1989)

(Kennedy, J., dissenting), most courts define “direct evidence” of motivation as

“conduct or statements by persons involved in the decisionmaking process that may

be viewed as directly reflecting the alleged [motivation).” Starceski v. Westinghouse

Elec. Corp., 54 F.3d 1089, 1096 (3d Cir. 1995)

15

Miller, 515 U.S. at 918; Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 959-62, 969-71

(1996) (plur. op.); Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 906. This evidence was

legally insufficient, even if uncontradicted, to permit a reasonable

finder of fact to conclude that plaintiffs had discharged their burden

of persuasion on the predominance issue. A court must “look further

than a map” to conclude that race was a state legislature’s

predominant consideration in drawing district lines as a matter of law.

Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529, 1565 (1995) (Hatchett, :.,

dissenting)."

By contrast, the summary judgment record contained substantial

direct evidence that race had not been the predominant factor in the

design of District 12. This evidence consisted of affidavits from the

legislators who headed the legislative committees that drew the 1997

plan and shepherded it through the General Assembly. See App. 69a-

84a. These legislators testified under oath that they and their

colleagues were well aware, when they designed and passed the 1997

plan, of the constitutional limitations imposed by this Court’s

decisions in Shaw I and its progeny, and that they took pains to ensure

that the plan did not run afoul of those limitations. They also testified

under oath that the boundaries of District 12 in the plan had been

motivated predominantly by partisan political concerns and other

legitimate race-neutral districting considerations, rather than by racial

considerations. At the summary judgment stage, the district court was

obligated to accept this testimony as truthful. See Liberty Lobby, 477

U.S. at 255 (“The evidence of the nonmovant is to be believed, and

all justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his favor.”). The district

court did precisely the opposite: it assumed that these state legislators

had lied under oath about the factors that motivated them in drawing

'» While the combination of a map and racial demographics may, under certain

extraordinary circumstances, be sufficient to state a claim that race was the

predominant factor in a district’s design, see Shaw I, there is a vast difference

between stating a claim and proving it.

16

the lines of District 12. That assumption was one this Court’s

precedents simply did not permit it to make at this stage of the

litigation. See id.; Miller, 515 U.S. at 915-16.

The district court’s application of the Rule 56 standard was so

irregular that summary reversal is warranted, even if this Court

concludes that the case does not present issues warranting plenary

consideration. “Striking down a law approved by the democratically

elected representatives of the people is no minor matter,” and this

Court’s precedents do not permit it do be done “on the gallop.”

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578, 626, 611 (1987) (Scalia, J.,

dissenting).

II. PRECLUSION ISSUE.

This case also raises important issues concerning the effect of a

final judgment from a court of competent jurisdiction holding a state’s

proposed redistricting plan constitutional on the ability of the parties

to that judgment and their privies to challenge the same plan again in

a later lawsuit before a different court.

Two of the plaintiffs herein -- Cromartie and Muse -- participated

as parties plaintiff in the remedial proceedings in Shaw. In those

proceedings, the court offered them a full and fair opportunity to

litigate any constitutional challenges they might have to the 1997

plan, which the State had proposed as a remedy for the constitutional

defects found in the earlier plan. They elected not to avail themselves

of that opportunity, and the Shaw court entered a final judgment

finding the plan constitutional and authorizing the State to proceed

with elections under it. Under elementary principles of claim

preclusion, that final judgment extinguished any and all claims

Cromartie and Muse had with respect to the validity of the 1997 plan,

including the claim they now assert in this action, which challenges

the plan’s District 1 as a racial gerrymander. That Cromartie and

Muse elected not to assert that particular claim in Shaw will not save

it from preclusion here; indeed, the very purpose of the doctrine of

17

claim preclusion is to prevent plaintiffs from engaging in this sort of

strategic claim-splitting.

The final judgment entered in Shaw also bars the claim plaintiffs

Everett, Froelich, Linville, and Hardaway assert in this action, which

challenges the 1997 plan’s District 12 as a racial gerrymander.

Though these individuals were not formally named as parties in Shaw,

they are bound by the final judgment entered in that case because

their interests were so closely aligned with those of the Shaw

plaintiffs as to make the Shaw plaintiffs their “virtual representatives”

in that earlier action."

Ignoring fundamental principles of claim preclusion, the district

court held that the final judgment entered in Shaw did not bar the

claims appellants assert here. App. 3a-4a. The court based this

conclusion on its understanding that the Shaw court “was not

presented with a continuing challenge to the redistricting plan.” App.

4a. To the extent the court meant that the Shaw court did not resolve

“A party may be bound by a prior judgment, even though he was not formally

named as a party in that prior action, when his interests were closely aligned with

those of a party to the prior action and there are other indicia that the party was

serving as the non-party’s “virtual representative” in the prior action. See Ahng v.

Allisteel, Inc., 96 F.3d 1033, 1037 (7th Cir. 1996); Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A. v.

Celotex Corp., 56 F.3d 343, 345-46 (2d Cir. 1995); Gonzalez v. Banco Cent. Corp.,

27 F.3d 751, 761 (1st Cir. 1994); Nordhorn v. Ladish Co., 9 F.3d 1402, 1405 (9th

Cir. 1993); Royal Ins. Co. of Am. v. Quinn-L Capital Corp., 960 F.2d 1286, 1297

(5th Cir. 1992); Jaffree v. Wallace, 837 F.2d 1461, 1467-68 (11th Cir. 1988). The

relationship between the Shaw plaintiffs and the four plaintiffs who challenge

District 12 in this action has many of the classic indicia of “virtual representation’:

close relationships between the parties and the nonparties, shared counsel,

simultaneous litigation seeking the same basic relief under the same basic legal

theory, and apparent tactical maneuvering to avoid preclusion. See Jaffree, 837 F.2d

at 1467.

18

the issue of the 1997 plan’s constitutionality, it was mistaken." To the

extent the court meant only that the Shaw plaintiffs chose to assert no

challenge to the 1997 plan in those earlier proceedings, it missed the

central point of the doctrine of claim preclusion, which bars claims

that were or could have been brought in the prior proceedings. The

district court’s holding on the preclusion issue presents substantial

questions warranting either plenary consideration or summary

reversal.

The district court’s decision conflicts directly with this Court’s

cases defining the preclusive effect of a prior federal judgment. As

those decisions make plain, when a federal court enters a final

judgment, that judgment stands as an “absolute bar” to a subsequent

action concerning the same “claim or demand” between the same

parties and those in privity with them, “not only as to every matter

which was offered and received to sustain or defeat the claim or

demand, but [also] as to any other admissible matter which might

have been offered for that purpose.” Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94

U.S. 351, 352 (1876).

The district court’s decision also conflicts with Federated Dep't

Stores, Inc. v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394 (1981). In that case, this Court

15 The Shaw court did not expressly reserve the claims in question for resolution

in a later proceeding. Though the Shaw plaintiffs asked it to “dismiss the action

without prejudice to the right of any person having standing to bring a new action

attacking the constitutionality of the [1997] plan,” App. 1864, the court declined to

do so. While the court stated that its approval of the plan was necessarily “limited

by the dimensions of this civil action as that is defined by the parties and the claims

properly before us,” and that it therefore did not “run beyond the plan’s remedial

adequacy with respect to those parties,” it specifically held the plan constitutional

“as to the plaintiffs . . . in this case.” App. 167a, 160a. The only claim the court

dismissed “without prejudice” was “the claim added by amendment to the complaint

in this action on July 12, 1996,” in which the Shaw plaintiffs “challenged on ‘racial

gerrymandering’ grounds the creation of former congressional District 1.” App.

158a. (emphasis added.) As the court recognized, this claim was mooted by its

approval of the 1997 plan. App. 165a, 168a.

19

made clear that a federal court may not refuse to apply the doctrine of

claim preclusion simply because it believes the prior judgment to be

wrong. Id. at 398. As this Court explained, the doctrine of claim

preclusion serves “vital public interests beyond any individual judge’s

ad hoc determination of the equities in a particular case,” including

the interest in bringing disputes to an end, in conserving scarce

judicial resources, in protecting defendants from the expense and

vexation of multiple duplicative lawsuits, and in encouraging relianc=

on the court system by minimizing the possibility of inconsistent

judgments. Id. at 401. The district court’s decision here -- a

transparent attempt to correct a perceived error in an earlier judgment

that the losing party failed to appeal -- flies in the face of this bedrock

principle of our civil justice system."

The policies behind the doctrine of claim preclusion are at their

most compelling when the claims in question seek to interfere with a

state’s electoral processes. The strong public interest in the orderly

administration of the nation’s electoral machinery requires efficient

and decisive resolution of any disputes regarding these matters." In

this case, the district court’s disregard of basic principles of claim

preclusion has resulted in the entry of two dramatically inconsistent

'® In addition, the district court’s decision conflicts, at least in principle, with the

decisions of at least six federal circuit courts applying the “virtual representation”

theory of privity. See cases cited supra note 14. This conflict is illustrative of the

widespread confusion in the lower federal courts as to the proper scope of the

“virtual representation” doctrine. See 18 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE'S

FEDERAL PRACTICE § 131.40[3][e][I][B] (3d ed. 1997) (collecting cases); 18

C. WRIGHT, ET AL., FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 4457 (1981) (same).

'7 Precisely for this reason, Congress has provided for a right of direct appeal to

this Court from any order of a three-judge court granting or denying a request for

injunctive relief in any civil action challenging the constitutionality of the

apportionment of congressional districts or the apportionment of any statewide

legislative body. See 28 U.S.C. § 1253; 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a).

20

judgments -- one ordering the State to go forward with its

congressional elections under the 1997 plan and the other enjoining

it from doing so -- which have left the State’s electoral process in

disarray. It has significantly prolonged final resolution of the legal

controversy over the constitutionality of North Carolina’s

congressional districts, wasting judicial resources, diverting the state

legislature from the business of governing, and causing the State’s

taxpayers to incur significant additional expense. It is difficult to

imagine a greater affront to the policies behind the doctrine of claim

preclusion, to core principles of state sovereignty and federalism, and

to the very integrity of the federal system of justice itself.

The district court’s resolution of the preclusion issue is so flatly

inconsistent with this Court’s precedents that summary reversal is

warranted, even if this Court concludes that the case does not present

issues warranting plenary consideration.

III. PREDOMINANCE ISSUE.

In Shaw I, this Court first recognized that a facially race-neutral

electoral districting plan could, in certain exceptional circumstances,

be a “racial classification” that was subject to strict scrutiny under the

equal protection clause. 509 U.S. at 642-44, 646-47, 649. Two years

later, in Miller, this Court set forth the showing required to trigger

strict scrutiny of such a districting plan: “that race for its own sake,

and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant

and controlling rationale in drawing its district lines.” 515 U.S. at

913 (emphasis added). To satisfy this standard, a plaintiff must prove

that the legislature “subordinated traditional race-neutral districting

principles . . . to racial considerations,” so that race was “the

predominant factor” in the design of the districts. Id. at 916; see id. at

928-29 (O’Connor, J., concurring) (strict scrutiny applies only when

“the State has relied on race in substantial disregard of customary and

traditional [race-neutral] districting practices”).

21

In Miller, this Court recognized that “[f]ederal court review of

districting legislation represents a serious intrusion on the most vital

of local functions,” that redistricting legislatures are almost always

aware of racial demographics, and that the “distinction between being

aware of racial considerations and being motivated by them” is often

difficult to draw. 515 U.S. at 915-16. For these reasons, this Court

directed the lower courts to “exercise extraordinary caution” in

applying the “predominance” test. Id. at 916; see id. at 928-29

(O’Connor, J., concurring) (stressing that the Miller standard is a

“demanding” one, which subjects only “extreme instances of [racial]

gerrymandering” to strict scrutiny)

In its various opinions in Bush, this Court made clear that proof

that the legislature considered race as a factor in drawing district lines

is not sufficient, without more, to trigger strict scrutiny. See 517 U.S.

at 958 (plur. op.); id. at 993 (O’Connor, J., concurring); and id. at

999-1003 (Thomas, J., joined by Scalia, J., concurring in judgment).

Nor is proof that the legislature neglected traditional districting

criteria sufficient to trigger strict scrutiny. See id. at 962 (plur. op.);

id. at 993 (O’Connor, J., concurring); id. at 1000-001 (Thomas, J.,

Joined by Scalia, J., concurring in judgment). Instead, strict scrutiny

applies only when the plaintiff establishes both that the State

substantially neglected traditional districting criteria in drawing

district lines, and that it did so predominantly because of racial

considerations. See id. at 962-63 (plur. op.) and at 993-94 (O’ Connor,

J., concurring) (emphasis added). Accord Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 906-

07; Lawyer v. Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186, 2194-95 (1997).

In this case, the North Carolina legislature, exercising the State’s

sovereign right to design its own congressional districts, selected a

number of traditional -- and race-neutral -- districting criteria to be

used in constructing the 1997 plan: contiguity, respect for political

subdivisions, respect for actual communities of interest, preserving

the partisan balance in the State’s congressional delegation,

preserving the cores of prior districts, and avoiding contests between

22

incumbents. All of these criteria were ones that this Court had

previously approved as legitimate districting criteria." The legislature

did not, however, select geographic compactness as a criterion to

receive independent emphasis in drawing the plan. The 1997 plan as

drawn does not neglect any of the traditional race-neutral districting

criteria the legislature set out to follow; to the contrary, it substantially

complies with all of them.

The district court nonetheless concluded that the legislature

“disregarded traditional districting criteria” in designing District 12,

because it failed to comply with two race-neutral districting principles

that it never purported to be following -- specifically, the criteria of

“geographical integrity” and “compactness.” App. 21a-22a. The court

believed the legislature’s apparent disregard of these two districting

principles in drawing District 12, together with evidence that the

district “include[s] nearly all of the precincts with African-American

population proportions of over forty percent which lie between

Charlotte and Greensboro,” and that it “bypasse[s]” certain precincts

with large numbers of registered Democrats, established that race,

rather than partisan political preference, had been the predominant

factor in the design of District 12. App. 19a-21a. This extreme

misapplication of the threshold test for application of strict scrutiny

in a case of such importance to the people of North Carolina warrants

plenary review for at least four reasons.

First, the district court’s reliance on District 12’s relative lack of

geographic compactness and geographical integrity was based on a

fundamental misunderstanding of the nature and purpose of the

18 See Miller, 515 U.S. at 916 (contiguity, respect for political subdivisions, and

respect for communities defined by shared interests other than race); Gaffney v.

Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 751-54 (1973) (preserving partisan balance); Karcher v.

Daggett, 462 U.S. 725, 740 (1983) (preserving the cores of prior districts and

avoiding contests between incumbents); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 580 (1964)

(ensuring “access of citizens to their representatives”).

23

“disregard for traditional districting criteria” aspect of the Miller

test.'” As this Court has explained repeatedly, a state’s deviation from

traditional race-neutral districting criteria is important in this context

only because it may, when coupled with evidence of racial

demographics, serve as “circumstantial evidence” that “race for its

own sake, and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s

dominant and controlling rationale in drawing district lines.” Miller,

515 U.S. at 913; see id. at 914 (“disclose[s] a racial design”); Bus/.,

517 U.S. at 964 (plur. op.) (“correlations between raci:l

demographics and [irregular] district lines,” if not explained “in terms

of non-racial motivations,” tend to show “that race predominated in

the drawing of district lines”). The notion is that when a state casts

aside the race-neutral criteria it would normally apply in districting to

draw a majority-minority district, it is very likely to have done so for

predominantly racial reasons. For this inquiry to serve its purpose, it

must focus not on the degree to which the challenged district deviates

from some set of race-neutral districting principles that a hypothetical

state -- or a federal court -- might find appropriate in designing a plan,

but rather on the precise set of race-neutral districting principles that

the particular state would otherwise apply in designing its districts,

' Indeed, this misunderstanding of the “traditional race-neutral districting criteria”

to which Miller refers drove the district court to the otherwise inexplicable

conclusion that plaintiffs had established -- as a matter of law -- that race was the

predominant factor in the design of District 12, but that they had not established --

as a matter of law -- that it was the predominant factor in the design of District 1.

App. 17a-22a. The evidence that racial considerations had played a significant role

in the line-drawing process was much stronger with respect to District 1 than to

District 12, for it was undisputed that District 1 is a majority-minority district

enacted to avoid a violation of § 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The only conceivable

explanation for the district court’s conclusion that District 12 was a racial

gerrymander as a matter of law, but District 1 was not, was its perception that

District 1 was not as “irregular” as District 12 and had better “comparative

compactness indicators.” App. 13a-14a.

24

were it not pursuing a covert racial objective. See Quilter v.

Voinovich, 981 F. Supp. 1032, 1045 n.10 (N.D. Ohio 1997), aff'd

118 S. Ct. 1358 (1998) (characterizing the inquiry as “designed to

identify situations in which states have neglected the criteria they

would otherwise consider in pursuit of race-based objectives”).

In this case, the district court evaluated District 12°s compliance

with traditional race-neutral districting criteria by reference to two

such criteria that the people of North Carolina have not required their

legislature to observe in districting: “geographic compactness” and

“geographical integrity.” In so doing, the district court apparently

relied on this Court’s frequent references to compactness as a

traditional race-neutral districting criteria. See, e.g., Shaw I, 509 U.S.

at 647; Miller, 515 U.S. at 916; Bush, 517 U.S. at 959-66 (plur. op.).

But this Court has never indicated that the race-neutral districting

criteria it has mentioned in its opinions are anything but illustrations.

See, e.g., Miller, 515 U.S. at 916 (describing “traditional race-neutral

districting principles” as “including but not limited to compactness,

contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions or communities

defined by actual shared interests’) (emphasis added). Nor has this

Court ever indicated that a state’s deviation from abstract numerical

measures of compactness has any probative value whatsoever when

the state in question does not have a stated goal of drawing compact

districts.”

2 Indeed, this Court’s recent decision in Lawyer suggests precisely the opposite.

In Lawyer, the plaintiffs presented evidence that the challenged state legislative

district encompassed more than one county, crossed a body of water, was irregular

in shape, and lacked geographic compactness. 117 S. Ct. at 2195. The district court

found this evidence insufficient to establish that traditional districting principles had

been subordinated to race in the district’s design, because these were all “common

characteristics of Florida legislative districts, being products of the State’s

geography and the fact that 40 Senate districts are superimposed on 67 counties.”

Id. (emphasis added). This Court upheld that finding, on the ground that the

“unrefuted evidence show(s] that on each of these points District 21 is no different

25

The district court’s decision effectively requires all states with

racially-mixed populations to comply with “objective” standards of

geographic compactness in drawing their congressional and

legislative districts. Such a requirement is flatly inconsistent with this

Court’s repeated statements that geographic compactness is not a

constitutionally-mandated districting principle. See Bush, 517 U.S. at

962 (plur. op.); Shaw I, 509 U.S. at 647. It also conflicts directly with

this Court’s long-standing recognition that the Constitution accords

the states wide-ranging discretion to design their congressional and

legislative districts as they see fit, so long as they remain within

constitutional bounds. See Quilter, 507 U.S. 156; Wise v. Lipscomb,

437 U.S. 535, 539 (1978). Surely this means that the states are

entitled to decide which particular race-neutral districting criteria they

will emphasize in drawing their districts, without worrying that strict

scrutiny will apply if a federal judge disagrees with their choices.”

Second, the district court’s decision conflicts directly with this

Court’s decision in Bush. There, a majority of this Court made clear

that a district is not subject to strict scrutiny simply because there is

some correlation between its lines and racial demographics if the

evidence establishes that those lines were in fact drawn on the basis

of political voting preference, rather than race. 517 U.S. at 968 (plur.

op.) (“If district lines merely correlate with race because they are

drawn on the basis of political affiliation, which correlates with race,

there is no racial classification to justify”); see id. at 1027-32

(Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting); id. at

from what Florida's traditional districting principles could be expected to produce.”

Id. (emphasis added).

2! This is not to suggest, of course, that a state could avoid the strict scrutiny of

Shaw and Miller simply by choosing to establish “minimal or vague criteria (or

perhaps none at all),” so that “it could never be found to have neglected or

subordinated those criteria to race.” Quilter, 981 F. Supp. at 1081 n.10. But that is

not what happened here.

26

1060-61 (Souter, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting).

Contrary to the district court’s suggestion, this is not a situation like

that in Bush, where the state has used race as a proxy for political

characteristics in its political gerrymandering. Instead, the undisputed

evidence in the summary judgment record showed that the State used

political characteristics themselves, not racial data, to draw the lines.

The legislature’s use of such political data to accomplish otherwise

legitimate political gerrymandering will not subject the resulting

district to strict scrutiny, “regardless of its awareness of its racial

implications and regardless of the fact that it does so in the context of

a majority-minority district.” Id. at 968 (plur. op.); see id. at 1027-32

(Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting); id. at

1060-61 (Souter, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting).

Third, the district court’s decision raises substantial, unresolved

questions concerning the circumstances under which a plaintiff can

satisfy the threshold test for strict scrutiny based solely on an

inference drawn from a district’s shape and racial demographics.

Miller held that a plaintiff can prove the legislature’s predominantly

racial motive with either “circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape

and demographics or more direct evidence going to legislative

purpose.” 515 U.S. at 916. In all of its prior cases finding the

threshold test for strict scrutiny met, however, this Court has relied

heavily on substantial direct evidence of legislative motivation. See

id. at 918 (relying on the State’s § 5 submissions, the testimony of the

individual state officials who drew the plan, and the State’s formal

concession that it had deliberately set out to create majority-minority

districts in order to comply with the Department of Justice’s “black

maximization” policy); Bush, 517 U.S. at 959-61, 969-71 (plur. op.)

(same); id. at 1002 & n.2 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment)

(same); Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 906 (same). As a result, this Court has

never confronted the question of how much circumstantial evidence

is enough to satisfy the Miller predominance standard, in the absence

27

of any direct evidence of racial motivation. See Miller, 515 U.S. at

917 (specifically reserving this issue).

The plaintiffs in this case, unlike those in Miller, Bush, and Shaw

11, base their claim that race was the predominant factor in the design

of Districts 12 solely on circumstantial evidence of shape and racial

demographics. Yet their circumstantial evidence is decidedly less

powerful than that presented by their counterparts in Miller, Bush,

and Shaw II. First, and most fundamentally, the district they challenge

is not a majority-minority district, as were the districts at issue in

those cases. This Court’s recent decision in Lawyer, which rejected

a claim that a challenged Florida state senate district was a racial

gerrymander, makes clear that this is an important distinction. 117 S.

Ct. at 2191, 2195 (emphasizing that the challenged district was not

majority-black and noting that “similar racial composition of different

political districts” is not “necessary to avoid an inference of racial

gerrymandering in any one of them.”). In addition, the shape of the

district challenged here, though somewhat irregular, does not reveal

“substantial” disregard for traditional race-neutral districting

principles.” Finally, the undisputed evidence here established that the

racial data the legislature used in designing these districts was no

more detailed than the other demographic data it used. Compare

Bush, 517 U.S. at 962-67, 969-71, 975-76 (plur. op.) (finding

22 In sharp contrast to former District 12, which this Court invalidated in Shaw II,

current District 12 is contiguous, respects the integrity of political subdivisions to

the extent reasonably possible, and creates a community of interest defined by

criteria other than race. While it has relatively low dispersion and perimeter

compactness measures, this is insufficient to support a finding that the legislature

“substantially” disregarded traditional districting criteria in designing it, even if

geographic compactness can be considered one of the State’s “traditional districting

criteria.” See Quilter, 981 F. Supp. at 1048 (expressing “doubt” that a state’s neglect

of one of its many traditional districting criteria “would be sufficient to show the

kind of flagrant disregard that would indicate that traditional districting principles

were subordinated to racial objectives”).

28

legislature’s use of racial data that was significantly more detailed

than its data on other voter demographics strong circumstantial

evidence that race had been its predominant consideration in

designing the challenged districts).

On this record, there is a substantial question whether plaintiffs’

evidence of shape and racial demographics is sufficient to support an

inference that race was the predominant factor in the design of

District 12. Indeed, the evidence of shape and demographics here

closely resembles that offered by the plaintiffs in Lawyer, which this

Court found insufficient to support an inference of racial

gerrymandering. See 117 S. Ct. at 2195. In addition, the state

defendants rebutted any such inference with substantial direct

evidence that partisan political preference, and not race, had been the

predominant factor in the district’s design. Under this Court’s

decisions, that should have been sufficient to avoid strict scrutiny, in

the absence of any direct evidence of racial motivation. See Shaw I,

509 U.S. at 653, 658 (indicating that State can avoid strict scrutiny by

“contradicting” the inference of racial motivation that arises from

plaintiffs’ evidence of shape and racial demographics); Miller, 515

U.S. at 916 (strict scrutiny does not apply where the state establishes

that “race-neutral considerations are the basis for redistricting

legislation, and are not subordinated to race”).

Finally, the district court’s decision sets far too low a threshold

for subjecting a state’s districting efforts to strict -- and potentially

fatal -- constitutional review. Under its reasoning, a private plaintiff

can trigger strict scrutiny of a state redistricting plan simply by

2 In an analogous “mixed motives” situation -- the individual disparate treatment

case under Title VII -- four members of this Court have endorsed a rule that would

require plaintiff to produce “direct evidence” that the impermissible criterion was

a substantial motivating factor in the challenged decision in order to prevail. Price

Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 275-76 (1989) (O’Connor, J., concurring),

290 (Kennedy, J., joined by Rehnquist, C.J. and Scalia, J., dissenting).

29

showing that its districts are somewhat irregular in shape and that

some of them have heavier concentrations of minority voters than

others. If strict scrutiny is this easily triggered, the states, particularly

those subject to the preclearance requirements in § 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, will find themselves in an impossible bind. If they take

race into account in districting, in order to avoid violating the Voting

Rights Act, they face private lawsuits under the Equal Protection

Clause; but if they do not, they face both denial of preclearance under

§ 5 of the Voting Right Act and private lawsuits under § 2. See Bush

517 U.S. at 990-95 (O’Connor, J., concurring) (noting the tension

between the Voting Rights Act, which requires the states to consider

race in districting, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which requires

courts “to look with suspicion on the[ir] excessive use of racial

considerations”). Nearly every plan they draw will be subject to

challenge on one ground or the other, nearly every plan will be the

subject of protracted litigation in the federal courts, and the federal

courts will become the principal architects of their congressional and

legislative districting plans. This Court should not tolerate such an

unprecedented intrusion by the federal judiciary into this “most vital”

aspect of state sovereignty. Miller, 515 U.S. at 915.

The district court’s extreme misapplication of the threshold test

for strict scrutiny illustrates the need for this Court to provide

additional guidance on its proper application in cases where there is

no direct evidence of racial motivation, the district in question is not

a majority-minority district, and it does not disregard the State’s stated

race-neutral districting criteria. This situation will arise with some

frequency in the next round of Shaw cases, particularly in states like

North Carolina, which remain subject to a realistic threat of liability

under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act if they do not pay close attention

to racial fairness in districting. As Justice O’Connor recognized in

Bush, these states -- and the lower courts -- are entitled to “more

definite guidance as they toil with the twin demands of the Fourteenth

30

Amendment and the VRA.” 517 U.S. at 990 (O’Connor, J.

concurring).

CONCLUSION

For the forgoing reasons, this Court should summarily reverse the

April 6, 1998 judgment of the district court and remand the case for

trial. In the alternative, this Court should note probable jurisdiction of

this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

North Carolina Attorney General

Edwin M. Speas, Jr.*

Chief Deputy Attorney General

Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

Melissa L. Saunders

Special Counsel to the Attorney General

July 6, 1998 *Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions of United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, April 14, 1998

Memorandum Opinion... ........ ..u. 5 Pid

DISSEAt si, i de eae

Order and Permanent Injunction of United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

North Caroling, April 3.1998 ........s iui

Notice of Appeal, April 6,1998 ...................

Judgment of United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, April 6, 1998 . . ..

Amended Notice of Appeal, April 8,1998 .........

Judgment of United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, April 14, 1998 ...

Order of United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, April 21, 1998 . ...

North Carolina 1997 Congressional Plan (map) ......

North Carolina 1992 Congressional Plan (map) ......

997C-27N of the Section 5 Submission Commentary,

Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett (CD47) .............

* Civil Docket

Affidavit of Senator Roy A. Cooper, III

(without attachments} {CD 47)... ue ie a 69a

Affidavit of Representative W. Edwin McMahan

(without attachment (CD 47) .5. .oiiitiivinin ing 79a

Affidavit of David W. Peterson, PhD

(withont attachment {CD 47) .... 0. vu vi ibn 85a

Affidavit of Dr. Alfred W. Stuart

(without attachments} (CD 47Y . ..... .oii livin. 101a

“An Evaluation of North Carolina’s 1998

Congressional Districts” by Professor

Gerald R. Webster (without maps) (CD 47) ......... 107a

Shaw, et al. v. Hunt, et al.,

CA No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, Order of United States

District Court for the Eastern District of

North Carolina, September 12,1997 ............... 157a

Shaw, et al. v. Hunt, et al.,

CA No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, Memorandum Opinion

of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina,

September 12,1997 crs or Tae 159a

U.S.CoNST.amend. XIV, 31... union a 169a

PED. RICIV. PASO 0. Jo ol eis on oa se oe 171a

Order of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, June 22, 1998 .. ... 175a

Shaw, et al. v. Hunt, et al.,

CA No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, Order of

United States District Court for the Eastern District

Of North Carchna, June 9, 1997... . 0. ci viii én 181a

Shaw, et al. v. Hunt, et al.,

CA No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR, Plaintiffs’ Response to

Order of June 9, 1997, June 19,1997 .............. 183a

[This page intentionally left blank]

la

OPINIONS OF UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, APRIL 14, 1998

[Caption Omitted in Printing]

MEMORANDUM OPINION *

This matter is before the Court on the Plaintiffs’

Motions for Preliminary Injunction and for Summary Judg-

ment, and on the Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment.

The underlying action challenges the congressional redistrict-

ing plan enacted by the General Assembly of the State of North

Carolina on March 31, 1997, contending that it violates the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and

relying on the line of cases represented by Shaw v. Hunt, 517

U.S. 899, 116 S. Ct. 1894, 135 L. Ed. 2d 207 (1996) (“Shaw

Ir’), and Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900,904, 115 S. Ct. 2475,

2482, 132 L. Ed. 2d 762 (1995). Ww :

Following a hearing in this matter on March 31, 1998,

the Court took the parties’ motions under advisement and

thereafter issued an Order and Permanent Injunction (1) finding

that the Twelfth Congressional District under the 1997 North

Carolina Congressional Redistricting Plan is unconstitutional,

and granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment as to

the Twelfth Congressional District; (2) granting Plaintiffs’

Motion for Preliminary Injunction and granting Plaintiffs’

request, as contained in its Complaint, for a Permanent Injunc-

tion, thereby enjoining Defendants from conducting any

2a

MEMORANDUM OPINION, CONTINUED. ..

primary or general election for congressional offices under the

redistricting plan enacted as 1997 N.C. Session Laws, Chapter

11; and (3) ordering that the parties file a written submission

addressing an appropriate time period within which the North

Carolina General Assembly may be allowed the opportunity to

correct the constitutional defects in the 1997 Congressional

Redistricting Plan, and to present a proposed election schedule

to follow redistricting which provides for a primary election

process culminating in a general congressional election to be