Harrison v. NAACP Brief and Appendix on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 13, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. NAACP Brief and Appendix on Behalf of Appellants, 1958. ea8f4c83-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79d8c76e-ae4f-45f7-85b6-62945826b85e/harrison-v-naacp-brief-and-appendix-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

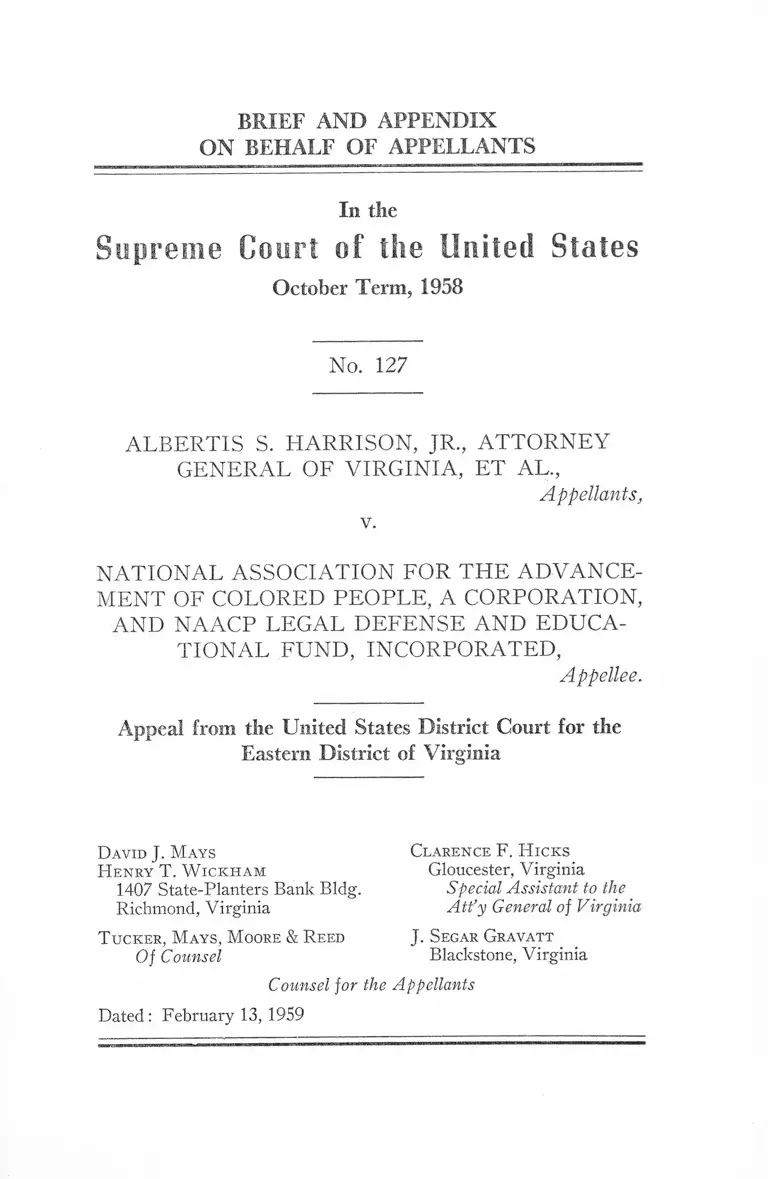

BRIEF AND APPENDIX

ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

In the

Supreme Court of the United Slates

October Term, 1958

No. 127

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, A CORPORATION,

AND NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCA

TIONAL FUND, INCORPORATED,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

D avid J. M ays

H enry T . W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

T u c k er , M ays, M oore & R eed

Of Counsel

Clarence F. H ic k s

Gloucester, Virginia

Special Assistant to the

A tt’y General of Virginia

J. S egar Gravatt

Blackstone, Virginia

Counsel for the Appellants

Dated: February 13, 1959

Opinion of the Court Below ...................................................... 1

J urisdiction of the Court........................................ -..... ............ 2

Statutes Involved ......................................................... -............... 2

Questions Presented................... .................................................. 2

Statement of Case............... ................................ ......................... 3

Operation of the NAACP ........................................ -................ 5

Operation of Legal Defense F u n d ...................................... ....... 7

Necessity for Chapters 31 and 3 5 ................................................ 9

Necessity for Chapter 32 ................. .... ...................................—. 12

Motives of Legislature __ _____ __-....................... -............... 14

Economic Reprisals ............... .... ................................................. 14

S ummary of Argument............. ............ .... ................................... 17

I. Court Below Should Have Declined to Exercise Its Equity

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... - 17

II. Registration Statutes Do Not Restrict Freedom of Asso

ciation in Such a Manner as to Violate the Due Process

Clause ................................. 19

III. Chapter 35 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause

or the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment 21

Argument .................................. ..... .... ........... ..........................— 22

I. The Court Below Should Have Declined to Exercise Its

Equity Jurisdiction ...................... 22

A. The Three-Judge District Court Should Not Have Re

strained Enforcement of Criminal Statutes of the Com

monwealth of Virginia.................................................... 22

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Page

B. The Court Below Erred in Holding That Proceedings

Should Be Stayed Only When Statutes Involved Are

Vague and Ill-defined .................................................... 29

C. The Majority Below Erred in Holding That the Stat

utes in Question Were So Free from Ambiguity as to

Need No Definite Adjudications in State Courts......... 37

II. The Registration Statutes Were Enacted Under the Valid

Exercise of the State's Police Power ........ .......................... 41

III. Chapter 35 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause

of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment 60

Co nclusio n ...................... .................... ..... ............. ...................... . 63

A ppe n d ix I :

Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia (Extra Session,

1956) :

Chapter 31 .................................................................... App. 1

Chapter 32 ................... ........................... ............. ....... App. 4

Chapter 35 .... ...... .......................... .............................. App. 9

A ppe n d ix II :

North Carolina Statute ...................................................... App. 11

A ppe n d ix I I I :

Alabama Statute .................................................. ............. App. 13

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

A. F. of L. v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582 ............ ........... ............ . 30, 31

Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 ............. .................. . 18, 30, 31

ii

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 323 U. S. 250 ...................................... 20,

Bradwell v. Illinois (16 Wall.) 130..................................................

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 ............................... ............ 31,

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 ............. 21, 51, 52, 54, 55,

Buck v. Gibbs, 34 F. Supp. 510........................................................

Burroughs v. United States, 290 U. S. 534 ............................... 21,

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296......... .................................. -

Daniel v. Family Security Life Insurance Co., 336 U. S. 220

Doud v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 ........................................................

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157..... ..................................... 18,

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315.................................... . 20,

Fletcher v. Peck, 6 Cranch 87 .......... ...... ....................................—

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464 .............................................. 42,

Government and Civil Employees v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364

18, 32, 33,

Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. Huffman, 319 U. S. 293 .........

Hannabass v. Maryland Casualty Co., 169 Va. 559 ........................

In re Issermen, 345 U. S. 286 .................................................... 62,

In re Lockwood, 154 U. S. 116........................................................

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92, cert. den. 355 U. S. 834 ....... 20,

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268..........................................................

Lassiter v. Taylor, 152 F. Supp. 295 ...............— ..........................

Lewis Publishing Company v. Morgan, 229 U. S. 288...................

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107.......................................... 21,

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .......................................... 21, 55, 56,

47

62

32

56

27

52

51

44

29

28

46

43

43

35

29

37

63

62

49

37

32

52

61

60

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People v.

Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 .............................................. ............... 1

Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176______ _____ ______ __ 22

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496 .. 18, 36

Sonzensky v. United States, 300 U. S. 506 ............................... 21, 52

Spillman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 296 U. S. 8 9 ................... 18, 27

Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 8 9 ............... 18, 36

Stefannelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117......... ................ .................... 28

Steiner v. Mitchell, 350 U. S. 247 ............................................... . 38

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197.............................................. 28

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516.............. ...................................... 51

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 ................... 18, 23

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612..................... 19, 20, 40, 44,

45, 50, 52

United States v. McKesson & Robbins, 351 U. S. 305 .................. 38

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178........................................ 44

Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 ....................... 18, 23, 24, 27, 28, 37

Statutes

Code of Virginia:

Section 19-265 ...................................... ....................................... 25

Sections 18-238 - 18-239 ...................................................... 25, 26

Sections 8-578 - 585 .................................................................... 36

United States Code:

2 U. S. C. Section 261 ............................................................... 45

2 U. S. C. Section 241 ............................................................... 52

26 U. S. C. Section 1132............................................................. 52

28 U. S. C. Section 1253 ......... 2

Page

iv

In the

Supreme Court of the United Slates

October Term, 1958

No. 127

ALBERTIS S. HARRISON, JR., ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, ET AL,

Appellants,

v.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, A CORPORATION,

AND NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCA- ’

TIONAL FUND, INCORPORATED,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

OPINION OF THE COURT BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond

Division, is reported at 159 F. Supp. 503 (1958) as

National Ass’n. for Advancement of Colored People v.

Patty.

2

THE JURISDICTION OF THE COURT

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U. S. C., Sec

tion 1253.

The final decree of the court below was filed on April 30,

1958 (R. 122). The notice for appeal was filed on May 22,

1958 (R. 124).

THE STATUTES INVOLVED

The validity of three state statutes is involved. Chapters

31 and 32, pp. 29-33, Acts of the General Assembly of

Virginia, Extra Session, 1956 (respectively codified as Sec

tions 18-349.9 et seq. and 18-349.17 et seq. of the Code of

Virginia, 1956 Additional Supplement, pp. 32-36) are reg

istration statutes. Chapter 35, pp. 36-37, Acts of the Gen

eral Assembly of Virginia, Extra Session, 1956 (codified as

Section 18-349.25 et seq. of the Code of Virginia, 1956

Additional Supplement, pp. 36-37) relates to the crime of

barratry. Due to the length of these statutes they are not

here set out verbatim. Their text is set forth as Appendix I

to this brief.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Under the facts of these cases, did the court below

err in restraining the enforcement of criminal statutes of

the Commonwealth of Virginia ?

2. Did the court below err in holding that proceedings

should be stayed only when state statutes under attack are

vague and ambiguous ?

3. Did the court below err in holding that the provisions

of the statutes in question were so free from doubt as to

not require definite adjudications in state courts?

3

4. Did the court below err in holding that all oi the

provisions of the registration statutes (Chapters 31 and 32)

violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment?

5. Did the court below err in holding that the barratry

statute (Chapter 35) deprived the appellees of rights guar

anteed by the Fourteenth Amendment ?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, hereinafter referred to as the NAACP, is a

membership corporation organized under the laws of the

State of New York (R. 498). It has local units or branches

which have been organized as unincorporated associations in

most of the states and the District of Columbia (R. 168).

The branches in Virginia are grouped into an association

called the Virginia State Conference and these branches

support the NAACP and the State Conference by the pay

ment of membership dues (R. 169-170).

Roy Wilkins heads the staff of the NAACP which is

responsible to a board of directors. The staff members

“preside over the functioning of the local branches through

out the country and the state conferences of branches” (R.

167). For all practical purposes the branches and the State

Conference are constituent parts of the NAACP (R. 505).

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Incorporated, hereinafter referred to as “Legal Defense

Fund”, is a New York membership corporation organized

for the following purposes as stated in its charter:

“ (a) To render legal aid gratuitously to such Ne

groes as may appear to be worthy thereof, who are

suffering legal injustice by reason of race or color and

4

unable to employ and engage legal aid and assistance

on account of poverty.

“ (b) To seek and promote the educational facilities

for Negroes who are denied the same by reason of race

or color.

“ (c) To conduct research, collect, collate, acquire,

compile and publish facts, information and statistics

concerning educational facilities and educational oppor

tunities for Negroes and the inequality in the educa

tional facilities and educational opportunities provided

for Negroes out of public funds; and the status of the

Negro in American life” (R. 28).

There is only a small number of members of the Legal

Defense Fund and no membership dues are required. Its

income is derived mainly from contributors who are solic

ited by letter and telegram from New York City (R. 293,

294).

The Legal Defense Fund has been approved by the State

of New York to operate as a legal aid society because of the

provisions of the barratry statute of New York (R. 314).

Thurgood Marshall is Director and Counsel of the Legal

Defense Fund and it is his duty to carry out the policies of

the board of directors (R. 278). He has under his direction

a legal research staff of six full time lawyers who reside in

New York City but who may be assigned to places outside

of New York (R. 279).

In addition to the full time staff, the Legal Defense Fund

has lawyers in several sections of the country on a retainer

basis and, in addition, approximately one hundred volunteer

lawyers throughout the country who come in to assist when

ever needed (R. 278). Spottswood W. Robinson, III, is

the Southeast Regional Counsel for the Legal Defense Fund

on an annual retainer. The southeast region includes the

Commonwealth of Virginia (R. 288, 303). The Legal De

5

fense Fund also has at its disposal social scientists, teachers

of government, anthropologists and sociologists, especially

in school litigation (R. 286).

The Operation of the NAACP

Speaking of the legal activity of the NAACP, Roy

Wilkins testified:

“Well, under legal activity we have sought to assist in

securing the constitutional rights of citizens which may

have been impaired or infringed upon or denied. We

have offered assistance in the securing of such rights.

Where there has been apparently a denial of those

rights, we have offered assistance to go to court and

establish under the Constitution or under the federal

laws or according to the federal processes, to seek the

restoration of those rights to an aggrieved party.” (R.

170,171)

Wilkins further testified that in assisting plaintiffs “we

would either offer them a lawyer to handle their case or to

help to handle their case and pay that lawyer ourselves, or

we would advise them, if they had their own lawyer, would

advise with them or assist in the costs of the case” (R. 177).

No money ever passes directly to the plaintiff or litigant

(R. 177).

The NAACP says publicly that it believes that a certain

law is invalid and should be challenged in the courts. Ne

groes are urged to challenge such laws and if one steps

forward, the NAACP agrees to assist (R. 179).

Although it is not in the regular course of business, pre

pared papers have been submitted at NAACP meetings

authorizing someone to act in bringing law suits and the

people in attendance have been urged to sign (R. 180).

Robert L. Carter, General Counsel for the NAACP, is

6

paid to handle legal affairs for the corporation. Repre

sentation of the various Virginia plaintiffs falls within his

duties. The NAACP offers “legal advice and assistance

and counsel, and Mr. Carter is one of the commodities”

(R. 203, 204).

The State Conference has a legal staff composed of thir

teen members and in every instance except two plaintiffs

have been represented by members of such staff in cases in

which assistance is given (R. 153).

All prospective plaintiffs are referred to the Chairman of

the Legal Staff, Oliver W. Hill, and counsel for such plain

tiffs makes his appearance when Hill has recommended that

they have “a legitimate situation that the NAACP should

be interested in” (R. 152).

The State Conference assists in cases involving discrim

ination and the Executive Board formulates certain policies

to be applied in determining whether assistance will be given.

Hill then applies these policies and when he decides that the

case is a proper one, it is taken “automatically” with the

concurrence of the President (R. 156).

Members of the Legal Staff of the State Conference

attend meetings held by the branches in their capacity as

counsel for the Conference and either the particular branch

or the State Conference pays the traveling expenses in

curred (R. 164).

Oliver W. Hill testified that he is not compensated as

Chairman of the Legal Staff. It is his duty to advise Ne

groes who come to him voluntarily “or directly from some

local branch, or after having been directed there by Mr.

Banks” whether or not he will recommend to the State Con

ference that their case will be accepted (R. 207).

After a case is accepted, Hill selects the lawyer (R. 209).

He refers the case to a member of the Legal Staff residing

7

in the particular area from which the complaining party

came. For the Richmond area, “one of us would frequently

handle the situation” (R. 208). A bill for the legal services

is submitted to Hill who approves it with the concurrence

of the President of the State Conference (R. 210).

Hill further stated that no investigation is made as to

the ability of the plaintiffs to pay the cost of litigation. He

feels that irrespective of wealth, a person has the right “to

get cooperative action in these cases” (R. 222).

The Operation of the Legal Defense Fund

Thurguod Marshall testified that it is the policy of the

Legal Defense Fund before sending assistance in a legal

case that the case must be referred to it by either the party

directly in interest or the party’s attorney. When aid is

given, the party’s attorney is controlled solely by the canons

of ethics and “by nothing or anybody else” (R. 280).

In the words of its Director and Counsel, the Legal

Defense Fund operates in the following manner:

“* * * If the investigation conducted either from the

New York office or through one of our local lawyers

reveals that there is discrimination because of race or

color and legal assistance is needed, we will furnish

that legal assistance in the form of either helping in

payment of the costs or helping in the payment of law

yers fees, and mostly it is legal research in the prepa

ration of briefs and materials of that type. We are

getting calls all the time.” (R. 279)

However, upon being examined concerning the meaning

of a letter received from the southwest regional counsel of

the Legal Defense Fund, Marshall stated that he assumed

that there were particular plaintiffs requesting aid when

it was stated that “Proposed legal action will include * * *

8

(c) Suits against strategically chosen school boards in

Eastern Louisiana contiguous to Mississippi” (R. 308, 309,

637).

In the same letter to which reference is made above the

following statement is found:

“* * * We have a statute making racial segregation

mandatory in the thirty-odd state owned and operated

parks in Texas. We shall undoubtedly strive to test

that law in 1956. In the past we have found it extreme

ly difficult to get persons to undertake to use the sensi

tive facilities such as restaurants, swimming pools,

dance facilities, and the like. We shall continue to press

that issue.” (R. 638, 639) (Italics supplied)

The Legal Defense Fund does not cooperate if a case is

referred by an organization including the NAACP (R.

280). However, the lawyer who has already been retained

by the party receiving aid from the Legal Defense Fund

is always on the legal staff of the State Conference of the

NAACP (R. 289).

When a so-called client comes to a member of the legal

staff of the State Conference, he may then receive aid, not

only from the full legal staff of the State Conference, but

also from the full legal staff of the Legal Defense Fund,

including the services of its southeastern regional counsel

(R. 292).

The testimony of Thurgood Marshall on cross-examina

tion indicated that the Legal Defense Fund represented

only those people who cannot afford to pay for litigation

(R. 314). However, he stated that he knew of no instance

in which an investigation was made to find out whether or

not any of the plaintiffs could pay the cost of the school

litigation in Arlington, Charlottesville, Newport News or

Norfolk (R. 315).

9

Marshall further admitted that if a plaintiff owned real

estate with a fair market value of $15,000.00, free and clear,

he would be in pretty good shape to finance his own law suit

(R. 316).

B. B. Rowe testified as to the fair market value of the

real estate owned of record by the plaintiffs in Newport

News school segregation case, the total value being in excess

of $280,000 (R. 453-456).

Robinson, on being examined as an adverse witness by

the defendants, stated that his duties do not require him to

obtain a credit report or look extensively into the financial

situation of the parties who may request assistance of the

Legal Defense Fund (R. 334). As to the type of investi

gation conducted he stated:

“I do not make an investigation beyond the point of

looking at the client, if the client comes into the office,

exercising judgment as to appearances as they do ap

pear, and considering those in the light of what I am

requested to do * * *” (R. 334)

Robinson further testified that the Legal Defense Fund

would represent all of the plaintiffs in a class action even

though all but one could afford the cost of the litigation

(R. 341).

The Necessity for Chapters 31 and 35

Five witnesses who were plaintiffs in the Prince Edward

County school segregation case testified on behalf of the

appellants. All of them admitted signing a paper that reads

in part as follows:

10

“ ‘AUTHORIZATION

To Whom It May Concern:

“ ‘I (we) do hereby authorize Hill, Martin and

Robinson, attorneys, of the City of Richmond, Vir

ginia, to act for and on behalf of me (us) and for and

on behalf of my (our) child (children) designated be

low, to secure for him (her, them) such educational

facilities and opportunities as he (she, they) may be

entitled under the Constitution and laws of the United

States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and to

represent him (her, them) in all suits, matters and

proceedings, or whatever kind or character, pertaining

thereto.” (R.422)

However, all of them also testified:

1. They did not know that they were plaintiffs in the

Prince Edward County school segregation case, which was

filed in 1951, until 1956.

2. When they signed papers they thought only that they

would obtain a better or new school for their children.

3. They have had no communication from Hill, Martin

or Robinson concerning the law suit (R. 346-374).

Another witness who was a plaintiff in the Charlottesville

school segregation case stated that he has had no conver

sation or written correspondence with Hill or Robinson, all

of his contacts having been through the NAACP (R. 374).

Moses C. Maupin, who was also a plaintiff in the Char

lottesville case, testified that he signed an authorization

paper at a meeting of the NAACP at which time no lawyers

were present (R. 377).

Otis Scott, also a plaintiff in the Prince Edward case,

said that he was told by Hill and Robinson that “they

wouldn’t take the case up for segregated schools. If they

11

taken the case at all it would be on a non-segregated basis”

(R. 476).

Viola Neal testified that she was a plaintiff in the Prince

Edward case and authorized her attorneys, Hill and Robin

son, to do what they thought best. She desired to end segre

gation in the public schools. On cross-examination she

stated:

1. She did not talk to Hill or Robinson between the time

of the school strike on April 23, 1951, and April 26 at which

time she signed the authorization papers1 (R. 479).

2. The authorization was signed before she had a con

ference with Hill or Robinson (R. 480).

3. Hill and Robinson had not discussed the Prince Ed

ward case with her until they came to see her about testi

fying in this case (R. 480).

George P. Morton, a Prince Edward resident, stated

that Hill and Robinson told him that the only way equal

facilities could be obtained was to have a non-segregated

school (R. 488).

vSarah B. Brooks, a plaintiff in the Charlottesville case,

testified on cross-examination that speakers at a public

meeting said “for all children and mothers who wanted

children to go to a better school to sign up.” She did not

know she was authorizing a law suit and no one explained

the authorization which she signed (R. 242-243).

Julian A. Sherman, a witness on behalf of the appellants

testified as follows:

1. He was the Eastern Representative of the Claims

Research Bureau of the Law Department of the Associ

1 The meeting at which Hill and Robinson were present and told the

Negroes that they were prepared to file suit to end segregation was

held on May 3 (R. 491).

12

ation of American Railroads, and participates in investi

gations of claims arising from personal injuries under the

Federal Employer’s Liability Act (R. 464-465).

2. Solicitation of personal injury claims is widespread

in Virginia, as well as in the rest of the country, and di

vision of fees is also widespread as well as offering of finan

cial inducements to solicit business. Running and capping

is indulged in by unethical attorneys and by laymen in their

employ (R. 464-465).

3. The information required by Chapter 31 would help

alleviate these conditions by supplying proof of the division

of fees and of maintenance, thus enabling more effective

prosecution (R. 465-466).

The Necessity for Chapter 32

Dr. Francis V. Simkins, professor of American History

at Longwood College, Farmville, Virginia, testified that he

has made a special study of Southern history. As to the

history of secret societies, he stated that the Union League,

formed in 1862 to promote patriotism in the North, spread

to the South where it became an organization of Negroes

and carpetbaggers. Its membership list was secret and

under that cloak of secrecy its members committed acts of

violence (R. 415-416).

The Ku-Klux Klan was the most important secret society

in the South. It was notorious for its secrecy and also ulti

mately became notorious for the crimes it committed (R.

415-416). The Klan has had the tendency to reappear

periodically and it exists today because of racial tensions

(R. 419). Statutes requiring the disclosure of membership

lists help curb the harmful activities of such organizations

(R. 419).

13

John Patterson, the Attorney General of Alabama, re

counted instances of racial disturbances and violence occur

ring in the State of Alabama, including the so-called “Mont

gomery bus boycott situation”, instances in Birmingham,

the towns of Maplesville, Marion and Tuskegee. General

Patterson then pointed out that such a registration law as

Chapter 32 “would help the authorities to enforce the law,

catch the offenders, and possibly help us identify organiza

tions that are working in certain areas so that we could take

preventive measures to prevent the things from happening

before they do” (R. 471-472).

The Superintendent of the Virginia State Police and four

county sheriffs testified that Chapter 32 would be of help in

law enforcement (R. 378).

The Sheriffs generally stated that an order to integrate

the public schools would cause more racial tension, possibly

bloodshed, and would raise difficult law enforcement prob

lems. Secret organizations would antagonize the situation

and in their opinion, the provisions of Chapter 32 would aid

in crime detection, the prevention of violence and would be

helpful in selecting additional deputies who may be needed

in time of racial disturbances (R. 384-411).

Sheriff C. F. Coates, on cross-examination, further testi

fied that a colored man had just complained to him that the

NAACP placed pressure on him to join its local Branch.

The testimony is as follows:

“A colored man in my community came to me, on

yesterday, and told me that the NAACP had put pres

sure on him to try to make him join the NAACP. He

refused to join. They instructed him that he had to

join and he had to vote like they said to vote, and if

there was any bloodshed in that community from inte

gration of the school that the NAACP was going to

be in the middle of it. He refused to join it. The head

14

of this organization, so he said, on account of him re

fusing to join their organization, had sent a bunch of

thugs around to his place to tear it up.” (R. 403)

The Motives of the Legislature

Harrison Mann, a member of the House of Delegates

from Arlington County, testified that he was the chief

patron of Chapters 31, 32, 33, 35 and 36 and was responsible

for the drafting of Chapters 32 and 35 prior to the special

session of the General Assembly held in 1956 (R. 430-431).

Mann’s reasons that prompted him to strive for the en

actment of the statutes in question were:

1. The Autherine Lucy incident in Alabama and the

violence ensuing therefrom (R. 428).

2. John Kasper was beginning his operations in Wash

ington, right across the Potomac River (R. 428-429).

3. Existing racial tension in Virginia (R. 428-429).

4. The Prince Edward plaintiffs’ ignorance of the fact

that they had brought a law suit (R. 431).

5. The actions of the NAACP in Texas in soliciting and

paying litigants (R. 436-437).

6. Charges of certain Arlington lawyers that the

NAACP was engaged in practicing law (R. 431).

7. Certain white organizations were commencing suits

in Maryland, Kentucky, Louisiana and elsewhere (R. 431).

8. The organization of the Defenders in Virginia and

the recurrence of the Ku-Klux Klan in Florida (R. 434).

Economic Reprisals

The appellees, in an attempt to substantiate their allega

15

tions of harassment, abuse and economic reprisals against

its members and contributors, called eight witnesses, two

being colored. Their testimony falls into two categories,

those who told of social reprisals and threats and those who

told of economic reprisals.

Jack C. Orndoff, a white plaintiff in the Arlington school

segregation case, withdrew from the case because of

abusive and threatening telephone calls and some letters

received after a newspaper listed the names of all of the

plaintiffs. No testimony was introduced to indicate that

Orndoff was a member of or contributor to the NAACP

or Legal Defense Fund (R. 230-233).

Mildred D. Brown, a resident of Charlottesville, testified

that she was a member and officer of the Charlottesville-

Albemarle Chapter of the Virginia Council on Human Re

lations. She started receiving threatening phone calls after

her name appeared in a newspaper in connection with the

organization of the said chapter on Human Relations in

August, 1956. She has received no such calls since Decem

ber, 1956 (R. 249). A cross was also burned in front of her

house on September 6, 1956. Mrs. Brown attributed the

cross-burning and some of the telephone calls at least in

directly to the activities of John Kasper and his White

Citizens Council (R. 249). Since August, 1956, Mrs.

Brown also has been shunned by some of her friends and

their children have been forbidden to play with her children.

There is no evidence that she is a member of or contributor

to the NAACP or the Legal Defense Fund.

Sarah Patton Boyle is an author who has been advocating

integration since 1951. Her articles in the field of race re

lations have been published as letters to the editor in the

Norfolk-Virginia Pilot, the Richmond Times-Dispatch and

the Charlottesville Progress. Mrs. Boyle also published

16

an article in the Christian Century and one in the Saturday

Evening Post. Since 1951 she has received over two hun

dred letters, the contents of which vary from being reason

able to extreme insults and threats of violence (R. 265).

The maker of one phone call threatened to have her husband

fired, and a cross was burned about fifteen feet from her

house (R. 265). The cross-burning is attributed, at least

in part, to the activities of John Kasper and his followers

(R. 268). Mrs. Boyle also stated that she has suffered pub

lic embarrassment and that her presence is now objection

able in certain social circles, all of which is a personal dis

tress to her (R. 266). The harrassment which she has

received in great volume was contributed to the article pub

lished in the Saturday Evening Post (R. 268). The evi

dence does not indicate that she is a member of or con

tributor to the NAACP or the Legal Defense Fund.

Mrs. Edith Burton, a member of the NAACP from

Arlington, wrote to the newspapers attacking the activities

of the Defenders, a pro-segregation organization. After

that time she received anonymous communications in the

form of letters and telephone calls. The phone calls have

now stopped (R. 251).

Mrs. Margaret I. Finner, a white member of the NAACP,

testified that she became a plaintiff in the Arlington school

segregation case because of Orndoff’s withdrawal. After

her name was published in the newspapers as being a plain

tiff, she received distressing anonymous communications

(R. 252).

Barbara S. Marx was one of the white plaintiffs in the

Arlington school segregation case, and she received dis

agreeable, obscene and threatening communications when

ever her name gets in the newspapers (R. 260). It was not

a secret that she was a member of the NAACP, and she

17

was well-known as a person promoting and advancing the

integration cause in Virginia long before the school case

(R. 262).

Robert D. Robertson, a Negro, stated that he was the

President of the Norfolk Branch of the NAACP. After

publicity was given to the fact that he requested the officials

of Norfolk County to protect those people living in a sub

division called “Coronado,” he received ugly and threaten

ing telephone calls. He also got similar calls whenever

Negroes got favorable court decisions such as in the Sea

shore State Park case and the Norfolk school segregation

case (R. 234, et seq.).

As to economic reprisals, Sarah B. Brooks, a cleaning

woman doing day work, testified that one of her employers

dismissed her after her name appeared in the newspaper as

being one of the plaintiffs in the Charlottesville school

segregation case (R. 239-241). There was no evidence

that she was a member of or contributor to the NAACP or

Legal Defense Fund. Furthermore, it was stipulated by

counsel that she has been fully employed by white employers

since the discharge mentioned aforesaid (R. 492).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The Court Below Should Have Declined to

Exercise Its Equity Jurisdiction

A. The exceptional circumstances necessary for a court

of equity to enjoin the enforcement of state criminal statutes

were not present in these cases. A real threat of prosecu

tion must be coupled with danger of great and irreparable

injury before a federal court, in the exercise of its equity

jurisdiction, will interfere with a state in the execution of

18

its criminal statutes. Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 (1941)

and Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943).

A general threat by state officials to enforce laws which

they are charged to administer ( United Public Workers v.

Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75, 88 (1947)) and the possibility of a

fine (Spillman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 89, 96

(1935)) are not sufficient for the exercise of equity juris

diction.

B. A federal court of equity should not decide that a

state statute is constitutional or unconstitutional until defi

nite determinations have been made by a state court. The

doctrine of equitable abstention is in furtherance of well

established policies of comity between state and federal

courts and of the principle that constitutional questions will

not be decided by federal courts unless they are unavoidable.

Government & C. E. 0. C., C.I.O. v. Windsor, 353 U. S.

364 (1957) ; Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S. 242 (1953) ;

Spector Motor Service, Inc. v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101

(1944) and Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co.,

312 U.S. 496 (1941).

While it is true that one of the reasons for declining to

exercise equity jurisdiction is that a particular statute is

vague and ambiguous, the court below erred in holding that

proceedings should be stayed only when the statute is vague

and ill-defined. The vast majority of the decisions of this

court make no such affirmative assertion. Compare the dis

sent in Albertson v. Millard, supra.

C. Even assuming that the court below properly stated

the doctrine of abstention, the provisions of the statutes in

volved in these cases are not so free from ambiguity as to

need no definite adjudications in the state courts.

19

The court below stated that Chapter 35, the barratry

statute, forbids the appellees to defray the expenses of

racial litigation. A careful reading of the definitions con

tained in Section 1 thereof leads the appellants to believe

that stirring up litigation must be coupled with the payment

of expenses of litigation before there is a violation of

Chapter 35.

Likewise, certain provisions of Chapter 32 were held to

be too broad or too vague to be constitutional. It is not

proper for a federal court of equity to predict that a state

court could not save the statute by construction. This Court

so construed the Federal Lobbying Act in United States v.

Harriss, 347 U. S. 612 (1954) as to overcome the objection

of unconstitutional vagueness.

Chapter 31 was declared unconstitutional for the same

reasons as Chapter 32. Again, assuming the reason of the

court below to be correct as to the applicability of the rule

of abstention, the provisions of the statutes before this

Court are not so definite, or so plainly unconstitutional that

a state court, by no interpretation, could find them consti

tutional, in whole or in part.

II.

The Registration Statutes Do Not Restrict Freedom of

Association in Such a Manner as to Violate the Due

Process Clause.

While the court below has declared that certain clauses

of Section 2 of Chapter 32 were either too broad or too

vague to meet constitutional requirements and has refused

to construe them in a constitutional manner, the primary

constitutional objection to the registration statutes appear

20

to be the requirement of the disclosure of membership lists

of the appellees.

The first clause of Section 2 of Chapter 32 provides for

the registration of persons who lobby “in any manner”.

Certainly, the state courts are able to construe this clause

to meet any constitutional objections that may be raised.

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612 (1954).

The facts disclosed in the record of these cases justify

the requirement, found in the second clause of Section 2 of

Chapter 32, that persons whose activities include “the advo

cating of racial integration or segregation” must register.

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250 (1952); Feiner v.

New York, 340 U. S. 315 (1951) and Kasper v. Brittain,

245 F. (2d) 92, cert. den. 355 U. S. 834 (1957).

The language, “cause or tend to cause racial conflicts or

violence” found in the third clause of Section 2 of Chapter

32 was condemned for vagueness. Again, could not a state

court, under the authority of United States v. Harriss,

supra, construe this language to meet the charge of uncon

stitutional vagueness? Further, this court in Beauharnais

v. Illinois, supra, did not condemn the phrase, “productive

of breach of the peace or riots” found in an Illinois criminal

statute. To the contrary, this Court approved of the state

court’s ruling characterizing the words prohibited by the

statute as those “liable to cause violence or disorder.”

Clause 4 of Section 2 of Chapter 32 and the provisions

of Chapter 31 provide generally for the registration of

those who solicit funds from the public for use in litigation.

Such persons are further required to file with the State

Corporation Commission a list of contributors and of mem

bers of organizations whose dues may be used to finance

litigation. Similar provisions or “restrictions” have been

approved in such cases as United States v. Harriss, supra;

21

Sonsensky v. United States, 300 U. S. 506 (1937); Bur

roughs v. United States, 290 U. S. 534 (1934).

The appellants contend also that the case of Bryant v.

Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 (1928), is in point and that this

Court’s decision on the due process question contained there

in was not based on the illegal aims of the organization.

The appellants further urge that this Court’s recent de

cision in N AACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958), may

be distinguished on the grounds that the facts in the record

in these cases clearly show that the enactment of the regis

tration statutes was justified as being in the public interest.

Finally, the court below erred in considering the legis

lative history of these statutes to determine the motives or

purposes of the state legislature, and in this “setting” in

passing upon their constitutionality.

III.

Chapter 35 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause

or the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

The court below misconstrued the provisions of Chapter

35 by holding that they prohibited the appellees from de

fraying the expenses of litigation. It is the appellants’

contention that the appellees must be shown to be guilty

of stirring up litigation before the defraying of expenses

of litigation becomes a crime. Based on this construction

no case has been found that holds that the exemption of

legal aid societies is an unreasonable classification. Chap

ter 35 is substantially similar to the common law offense

of barratry and does not violate the Due Process Clause.

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107 (1920).

22

ARGUMENT

I .

The Court Below Should Have Declined to

Exercise Its Equity Jurisdiction

The attendant facts of these cases require discussion of

three separate principles or rules of equity. The first is the

time-honored equity principle that courts ordinarily will

not enjoin the enforcement of a criminal statute. The sec

ond is based upon public policy and is well stated by Mr.

Justice Stone in Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176,

185 (1935):

“It is in the public interest that federal courts of

equity should exercise their discretionary power to

grant or withhold relief so as to avoid needless ob

struction of the domestic policy of the states.”

The third rule or principle to be discussed is that federal

courts are loath to pass on a federal constitutional question

when there is another non-constitutional question which may

well dispose of the case in a state court. An authoritative

construction of a state statute by a state court may void the

necessity for determining a federal constitutional question.

A.

T h e T h r e e - J udge D ist r ic t Court S h ou ld N ot H ave

R e str a in ed t h e E n fo r c em en t of Cr im in a l S ta t

u tes of t h e C o m m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia .

The record in these cases does not show that the appellees

were threatened with prosecution under the provisions of

Chapters 31, 32 or 35. Further, it has been uniformly held

that a general threat by state officials to enforce laws which

23

they are charged to administer is not sufficient for the exer

cise of equity jurisdiction. United Public Workers v. Mitch

ell, 330 U.S. 75, 88 (1947).

Certain facts in Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387 (1941),

are strikingly similar to circumstances surrounding these

cases. There, the American Society of Composers, Authors

and Publishers (ASCAP) together with individual com

posers, authors and publishers of music controlled by

ASCAP brought suit to restrain the Attorney General of

Florida and all state prosecuting attorneys, who were

charged with the duty of enforcing certain parts of two

Florida statutes, from enforcing a 1937 statute and certain

sections of a 1939 statute. The complaint alleged that the

defendants “had threatened to—and would, unless restrained

—enforce” the statutes in question. The defendants in their

answer specifically denied that they have made any threats

to enforce the statutes but admitted as to the 1939 law that

they would perform all duties imposed upon them by such

law. This Court made the following observation concern

ing the question of threats of prosecution in the Watson

case at page 399:

“* * * The most that can possibly be gathered from

the meager record references to this vital allegation of

complainants’ bill is that though no suits had been

threatened, and no criminal or civil proceedings in

stituted, and no particular proceedings contemplated,

the state officials stood ready to perform their duties

under their oath of office should they acquire knowledge

of violations. * * *”

The appellees in the instant cases merely alleged in their

complaints that the appellants were charged with the en

forcement of Chapters 31, 32 and 35. In response, the

appellants stated that their duties and responsibilities were

24

fixed by law. No evidence was introduced to the effect that

the appellants had threatened to prosecute suits against the

appellees or take action against anyone under the statutes.

It must be concluded, then, that the language of this Court,

quoted above, is applicable to the facts of these cases.

This Court concluded in Watson v. Buck, supra, at p. 401,

that “neither the findings of the court below nor the record

on which they were based justified an injunction against the

state prosecuting officers” and said:

“* * * The clear import of this record is that the

court below thought that if a federal court finds a

many-sided state criminal statute unconstitutional, a

mere statement by a prosecuting officer that he intends

to perform his duty is sufficient justification to warrant

the federal court in enjoining all state prosecuting offi

cers from in any way enforcing the statute in question.

Such, however, is not the rule. ‘The general rule is that

equity will not interfere to prevent the enforcement of

a criminal statute even though unconstitutional. . . .

To justify such interference there must be exceptional

circumstances and a clear showing that an injunction

is necessary in order to afford adequate protection of

constitutional rights. . . . We have said that it must

appear that ‘the danger of irreparable loss is both great

and immediate;’ otherwise the accused should first set

up his defense in the state court, even though the valid

ity of a statute is challenged. There is ample oppor

tunity for ultimate review by this Court of federal

questions.’ Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295

US 89, 95, 96, 79 L ed 1322, 1325, 1326, 55 S Ct 678.”

(313 U. S. 400-401)

The court below appeared to recognize that in the absence

of danger of great, immediate and irreparable injury, a

federal court, in the exercise of its equity jurisdiction, will

not interfere with a state in the execution of its criminal

25

statutes. However, it concluded that the facts “abundantly”

justified the exercise of its equitable powers. What are such

facts ? They may be placed under four headings and, as

stated in the words of the court below, are:

' - - r ■ '

1. The penalties prescribed by the statutes are heavy

and under Chapter 32 each day’s failure to register consti

tutes a separate offense ;

2. The deterrent effect of the statutes upon the acquisi

tion of members;

3. The deterrent effect of the statutes upon the lawyers

of the appellees under the threat of disciplinary action; and

4. The danger of immediate and persistent efforts on the

part of state authorities to interfere with the activities of

the appellees f 159 F. Supp. 521).

Persons violating the provisions of Chapters 31, 32 and

35 are deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and Section 19-265

of the Code of Virginia, 1950, reads as follows:

“A misdemeanor, for which no punishment or no

maximum punishment is prescribed by statute, shall be

punished by fine not exceeding five hundred dollars or

confinement in jail not exceeding twelve months, or

both, in the discretion of the jury or of the trial justice,

or of the court trying the case without a jury.”

Certainly it cannot be held that a misdemeanor penalty

is so “heavy” as to be deemed “exceptional circumstances”

for enjoining the enforcement of a state criminal statute.

Further, the provisions of Chapters 31 and 32 to the effect

that persons who knowingly make a false or fraudulent

affidavit shall be guilty of a felony and punished as provided

by Sections 18-238 and 18-239 of the Code of Virginia,

26

1950, cannot be said to be so unusual or heavy as to warrant

the interference of a court of equity. Sections 18-238 and

18-239 read, respectively, as follows:

“If any person commit or procure another person to

commit perjury, he shall be confined in the penitentiary

not less than one nor more than ten years; or, in the

discretion of the jury, be confined in jail not exceeding

one year, or fined not exceeding one thousand dollars,

or both.”

“He shall, moreover, on conviction thereof, be ad

judged forever incapable of holding any post mentioned

in §2-26, or of serving as a juror.”

Since, of course, corporations are not jailed, a fine not to

exceed ten thousand dollars, as provided by the provisions

of Chapters 31, 32 and 35, cannot be considered excessive

or “heavy”. Also, placing individual responsibility upon

the officers and directors of a corporation to see that a fine

for violation of Chapters 31 and 32 is paid is not unusual

under our jurisprudence.

Chapters 31 and 35 provide that foreign corporations

violating the provisions thereof shall have their certificates

of authority to transact business in Virginia revoked by

the State Corporation Commission. Again, such a penalty

is not foreign to our system of laws.

Chapter 32 does provide that each day’s failure to regis-

f ter shall constitute a separate offense. However, can it be

j *

} prophesied that a jury or trial court would place an excessive

fine on a corporation which in good faith did not register

because it was advised, for example, that the provisions of

Chapter 32 were not applicable to it ? Conceding that such

a penalty is not usually found in many criminal statutes it is

not unknown. Furthermore, assuming that it is too “heavy”

and necessitates interference by a court of equity as the

27

court below found, does it follow that the enforcement of

a barratry statute and a registration statute, with normal

criminal provisions, should likewise be enjoined? The cases

decided by this Court answer this question in the negative.

The possibility of a fine is a consequence hardly demand

ing the interference of any court of equity. Spillman Motor

Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S. 89, 96 (1935).

As to the deterrent efifect of the statutes upon the acqui

sition of members, it is to be noted that the complainants

in Watson v. Buck, supra, claimed that the Florida laws

were “confessedly aimed at ASCAP and its constituent

members” and would virtually destroy them. Buck v. Gibbs,

34 F. Supp. 510, 513-514 (1940). Even this was not enough

to warrant the interference of a federal court of equity.

Moreover, the court below was not justified in implying

that the appellees could not obtain relief from the “deterrent

effect” in a state court. It should also be pointed out that

this “deterrent effect” could be applicable only to Chapters

31 and 32. The barratry provisions of Chapter 35 could

have no effect on the acquisition of members.

As to the fact that the statutes had a deterrent effect upon

the lawyers of the appellees “under the threat of disciplinary

action”, it has already been pointed out that the record in

these cases does not justify such a finding of fact. The

lawyers have been threatened by no one. Again, such a fact,

if indeed true, could not justify an interference with the

registration provisions of Chapters 31 and 32. The lawyers

of the appellees, of course, stand in danger of disciplinary

action if they are guilty of stirring up litigation. All other

members of the Virginia bar stand in like danger.

Finally, there is nothing in the record to show that state

authorities have made persistent efforts to interfere with

the activities of the appellees. To repeat, there have been

no threats of prosecution.

28

In Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943), this Court

held that the facts of the case did not justify the restraint

of threatened criminal prosecutions of members of Jehovah’s

Witnesses. The complaint was dismissed even though the

challenged ordinance was (1) unconstitutional; (2) convic

tions and threats of convictions had occurred under the

ordinance; and (3) there were numerous members of a

class threatened with prosecution.

Assuming for sake of argument that the penalties show

great and irreparable injury to the appellees, the court below

has ignored the principle that such injury must be coupled

with actual threats of prosecution. Such threats are not

present in these cases. Language in Watson v. Buck, supra,

is again material and controlling. There, this Court said at

page 400:

“* * * The imminence and immediacy of proposed

enforcement, the nature of the threats actually made,

and the exceptional and irreparable injury which com

plainants would sustain if those threats were carried

out are among the vital allegations which must be

shown to exist before restraint of criminal proceed

ings is justified. * * *”

Compare Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197 (1923),

where the plaintiff would have had to risk confiscation of

his real property in order to test the validity of a state stat

ute in a criminal prosecution.

To conclude, it is appropriate to quote the following lan

guage from Stefanelli v. Minord,, 342 U. S. 117, 120 (1951),

which dealt with the discretion of federal courts in enjoining

state criminal proceedings:

“* * * Here the considerations governing that dis

cretion touch perhaps the most sensitive source of fric

29

tion between States and Nation, namely, the active

intrusion of the federal courts in the administration of

the criminal law for the prosecution of crimes solely

within the power of the States.”

B.

T h e Court B elow E rred in H olding T h a t P roceed

in g s S h ou ld B e S tayed O n ly W h e n t h e S ta tu tes

I nvolved A re V ague and I l l -d e f in e d .

The doctrine of equitable abstention is here involved. It

is invoked by a federal court of equity, even though a show

ing of danger of great and immediate injury is present, in

the furtherance of well established public policies, namely:

1. Proper comity between state and federal courts re

quires scrupulous regard for the rightful independence of

state governments and their courts, and

2. The principle that federal courts should refrain from

decision on constitutional questions unless it is unavoidable.

The exhaustive dissenting opinion of the court below on

the question here presented, found at 159 F. Supp. 540-548,

ably expresses the views of the appellants. There, the

dissenting judge concluded that the decisions of this Court

do not support the holding that proceedings should be

stayed only where an ill-defined statute is involved.

The appellants do not disagree with the decision in Doud

v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 (1956), cited by the majority below,

to the effect that the three-judge district court had jurisdic

tion of these cases. The withholding of equitable relief under

the doctrine of absention is not a denial of the jurisdiction

which Congress has conferred on the federal courts. Great

Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. v. Huffman, 319 U. S. 293, 297

(1943).

30

The following language found in the majority opinion

below is also approved by the appellants:

“See also A. F. of L. v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582, 599,

66 S. Ct. 761, 90 L. Ed. 873, where, in directing a dis

trict court to retain a suit involving the constitutionality

of a state statute pending the determination of pro

ceedings in the state courts, the Supreme Court said

that the purpose of the suit in the federal court would

not be defeated by this action, since the resources of

equity are adequate to deal with the problem so as to

avoid unnecessary friction with state policies while

cases go forward in the state courts for an expeditious

adjudication of state law questions.” (159 F. Suop. at

p. 522)

Furthermore, A. F. of L. v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582

(1946), does not stand for the proposition that federal

courts of equity should stay proceedings only where it is

reasonably possible for a state statute to be given an inter

pretation which will render it constitutional. Such does not

appear as an affirmative assertion. In the late Mr. Justice

Murphy’s dissent at page 606 he stated:

“* * * ]3ut there are federal constitutional issues in

herent on the face of this provision that do not depend

upon any interpretation or application made by Florida

courts. Those issues were raised and decided in the

court below. And they should be given appropriate

attention by this Court.”

A federal court of equity should not decide that a state

statute is constitutional or unconstitutional until definite

determinations have been made by a state court. This is true

even though the provisions of such statute appear to be free

of doubt or ambiguity. Albertson v. Millard, 345 U. S.

242 (1953).

31

In the Albertson case, the Communist Party of Michigan

and its Executive Secretary brought suit in a federal court

to enjoin the enforcement of the Michigan Communist

Control Bill, requiring the registration of Communists, the

Communist Party and Communist front organizations, on

the ground that it was unconstitutional vague. The three-

judge district court held that the statute was constitutional

and this Court vacated the judgment with directions to hold

the proceedings in abeyance pending state court construction

of the statute. While it is true that a state court proceeding

on the statute was pending at the time of this Court’s deci

sion, it was brought after the proceeding began in the

federal courts. This fact is not decisive in view of this

Court’s directive at page 245 “to hold the proceedings in

abeyance a reasonable time pending construction of the stat

ute by the state courts either in pending litigation or other

litigation which may be instituted.”

As in vl. F. of L. v. Watson, supra, the dissent in the

Albertson case makes it clear that this Court approves the

application of the doctrine of equitable absention even

though a statute is not ill-defined in the view of a three-

judge federal court. In the latter dissent, Mr. Justice Doug

las felt that the case should be disposed of on its merits since

there were no abstract questions or ambiguities involved and

since it was plain beyond argument that the complainants

were covered by the statute.

The majority of the court below cited three other decisions

of this Court, without analysis, and apparently based its

decision mainly upon a dissenting opinion of the late Chief

Judge Parker in Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (D.C.

E.D.S.C., 1957), in holding:

“The policy laid down by the Supreme Court does

not require a stay of proceedings in the federal courts

32

in cases of this sort if the state statutes at issue are

free of doubt or ambiguity. * * *” (159 F. Supp. 503,

533)

However, in the later case of Lassiter v. Taylor, 152 F.

Supp. 295 (D. C. E.D. N.C., 1957), a three-judge federal

court of which Chief Judge Parker was also a member

handed down a per curiam opinion involving a statute pre

scribing a literacy test for voters.2 The only question in the

case was whether the statute should be declared void on the

ground that it was violative of the complainants’ rights

under the Federal Constitution. The action was stayed on

the following ground:

“Before we take any action with respect to the Act

of March 27, 1957, however, we think that it should be

interpreted by the Supreme Court of North Carolina

in the light of the provisions of the State Constitution.

Government and Civic Employees Organizing Com

mittee etc. v. S. F. Windsor, 77 S. Ct. 838. * * *”

(152 F. Supp. at p. 298)

The case of Government & C. E. O. C., CIO v. Windsor,

353 U. S. 364 (1957), relied upon in Lassiter v. Taylor,

supra, was decided by this Court after Bryan v. Austin,

supra, and it must be assumed that chief Judge Parker, him

self, recognized that the Windsor case did not stand as

authority for the rule that a federal court of equity should

stay an action only when the state statute involved was

vague and ambiguous. In other words, the majority below,

relying upon the dissenting opinion in Bryan v. Austin,

committed error by ignoring the later case of Lassiter v.

Taylor and misconstruing the Windsor decision.

In the Windsor case this Court held that a three-judge

2 For the text of the statute, see Appendix II of this brief.

33

district court must neither decide that a state statute is

constitutional nor decide that it is unconstitutional until

after definite determinations had been made by the state

courts.

An examination of the factual background of the Wind

sor case leads to the inescapable conclusion that the merits

of these cases should not have been reached by a three-judge

federal court at this time. There, a labor organization and

one of its members who was employed by the Alabama

Alcoholic Beverage Control Board (A. B. C. Board) filed

suit in a federal district court seeking a declaratory judg

ment and an injunction to restrain the enforcement of a

statute referred to as the Solomon Bill.3 The defendants

were officials of the A. B. C. Board. Section 2 of the statute

provides:

“Section 2. Any public employee who joins or par

ticipates in a labor union or labor organization, or who

remains a member of, or continues to participate in,

a labor union or labor organization thirty days after

the effective date of this act, shall forfeiture all rights

afforded him under the State Merit System, employ

ment rights, re-employment rights, and other rights,

benefits, or privileges which he enjoys as a result of this

public employment.”

Although no employee of the A. B. C. Board had been

threatened with deprivation of his rights under the pro

visions of Section 2, quoted above, officials had informed

the union that the statute would be enforced in the same

manner as other pertinent laws.4

3 The full text of the Alabama Statute is set forth as Appendix III

of this brief.

4 It is also to be noted that two hundred and fifty employees of the

A. B. C. Board were members of the union before the passage of the

statute while only one or two continued membership after passage.

(78 So. (2nd) 646, 649).

34

The complainants urged that the Solomon Bill was sub

ject to no possible construction other than that of uncon

stitutionality under the Due Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment since the Alabama legislature had used

“unmistakably simple, clear and mandatory language”. The

district court applied the doctrine of equitable abstention

and withheld the exercise of its jurisdiction pending an

exhaustion of state judicial remedies. It observed that the

statute could be construed to meet the challenge of uncon

stitutionality (116 F. Supp. 354). This Court affirmed the

judgment (347 U. S. 901).

The union then filed suit in a state circuit court praying

for a declaratory judgment to determine its status under

the Solomon Bill. The Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed

the final decree of the circuit court which had held that the

statute was applicable to the union, its activities and its

members. (262 Ala. 785, 78 So. (2nd) 646).

At this stage of the proceedings, the state court had made

a determination that the Solomon Bill was applicable to the

complaining union and its members. The other sections of

the statute could not be termed vague and ambiguous. Ac

cordingly, when the case was again submitted to the three-

judge district court for final decree, it was dismissed with

prejudice on the ground that the Alabama court had not

construed the statute in such a manner as to render it un

constitutional (146 F. Supp. 214).

This Court reversed the second judgment of the three-

judge district court “with directions to retain jurisdiction

until efforts to obtain an appropriate adjudication in the

state courts have been exhausted”. In so doing, this Court

said:

35

“* 5,1 * In an action brought to restrain the enforce

ment of a state statute on constitutional grounds, the

federal court should retain jurisdiction until a definite

determination of local law questions is obtained from

the local courts. * * * The bare adjudication by the

Alabama Supreme Court that the union is subject to

this Act does not suffice, since that court was not asked

to interpret the statute in light of the constitutional

objections presented to the District Court. If appel

lants’ freedom-of-expression and equal-protection argu

ments had been presented to the state court, it might

have construed the statute in a different manner. * * *”

(353 U. S. at page 366)

The similarity of the facts in the Windsor case with the

facts of these cases is striking. In both, constitutional ques

tions concerning the alleged abridgements of freedom of

speech and association were presented to the three-judge

district courts. The effect of the passage of the Alabama

statute and two of the Virginia statutes here involved was

found by the courts below to have brought about a loss of

members and a resulting reduction of the revenues of the

complainants. The penalties prescribed by the Alabama

statute were of as great, if not greater, severity. Finally,

there had been no actual enforcement of the statutes in

either state. It should also be noted that there is nothing

in the record of these cases to uphold the majority’s state

ment that a multiplicity of suits would be prevented by the

exercise of the court’s equity jurisdiction.

In these cases, the majority below clearly should have

withheld a decision on the merits under the authority of

the Windsor case. By doing otherwise, it has made a tenta

tive answer which may be displaced tomorrow by a state

adjudication. “No matter how seasoned the judgment of the

district court may be, it cannot escape being a forecast

36

rather than a determination”. Railroad- Commission of

Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496, 499 (1941).

The appellees could have proceeded in a state court under

Virginia’s Declaratory Judgment Act (Sections 8-578-585

Chapter 25, Title 8, Vol. 2, pp. 407-411, Code of Virginia,

1957 Replacement Volume), as indeed they have as to Chap

ters 33 and 36, Acts of Assembly of Virginia, Extra Ses

sion, 1956, in accordance with the directions of the Court

below. If the majority of the Court below had so directed,

the rights of the appellees would have been fully protected

and a state court would have had the opportunity to con

sider the statutes here involved in light of the constitutional

questions raised below. This would have been in accord

with the Windsor case. Further, the majority below would

have avoided forecasts of local laws which the decisions of

this Court condemn. Spector Motor Service, Inc. v. Mc

Laughlin, 323 U. S. 101 (1944).

Finally, it must be emphasized that the majority below

declared Chapters 31, 32 and 35 unconstitutional in toto.

The Virginia legislature expressed a purpose directly con

trary to this finding as to Chapter 32 by the enactment of

Section 8 hereof. It reads:

“If any one or more sections, clauses, sentences or parts

of this act shall be adjudged invalid, such judgment

shall not affect, impair or invalidate the remaining

provisions thereof, but shall be confined in its operation

to the specific provisions held invalid, and the inapplica

bility or invalidity of any section, clause or provision

of this act in one or more instances or circumstances

shall not be taken to affect or prejudice in any way its

applicability or validity in any other instance.”

As to Chapters 31 and 35, the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia has repeatedly applied the test of separability,

37

even in the absence of a saving provision. Hannabass v.

Maryland Casualty Co., 169 Va. 559 (1938).

There are many clauses and sections of the statutes before

this Court and the majority below made no attempt to save

any parts thereof. Similar action was condemned by this

Court in Watson v. Buck, supra, at pp. 395-396.

If a state court struck down the requirements of revealing

lists of contributors and members to the public, could it be

said beyond doubt that the remaining provisions of Chap

ters 31 and 32 would abridge free speech and association

or fall by reason of legislative intent ? At the least, questions,

of law remain undecided which should be first considered by

the state courts.

C.

T h e M a jo r it y B elow E rred in H olding T h a t t h e

S t a tu tes in Q u e st io n W ere S o F ree from A m b i

g u it y as to N eed N o D e f in it e A d ju d ic a t io n s in

S ta te Co urts.

The appellants contend that even under the lower court’s

application of the doctrine of equitable abstention decision

in these cases should have been stayed at that time.

The majority below discussed at great length what was

claimed to be the legislative history of the statutes in these

cases. It was asserted in a footnote that this is necessary

and “of the highest relevance” when a claim of unconsti

tutionality is put forward. The case of Lane v. Wilson, 307

U. S. 268 (1939) is relied upon to uphold such an assertion.

However, a perusal of that decision does not reveal that

such a rule was announced therein.

The appellants do not believe that mere assertion of a

claim that a statute is unconstitutional could change long

established rules of statutory construction. The legislative

38

history of a statute is immaterial when its language is un

ambiguous. United States v. McKesson & Robbins, 351 U.

S. 305 (1956) and Steiner v. Mitchell, 350 U. S. 247

(1956).

While disclaiming the need for interpretation on the

ground that the state statutes are free of doubt, the majority

below has proceeded to interpret the statutes and to base

such interpretation, in part at least, upon legislative history.

This assumption of power to interpret speaks eloquently

for the fact that, even under the limited application of the

doctrine of abstention adopted by the majority below, de

cision on the constitutionality of the state statutes should

not have been reached.

The barratry statute (Chapter 35) under consideration

in these cases denounces as a crime the offense of stirring

up litigation. Definitions are set forth in Section 1 and

read, in part, as follows:

“ (a) ‘Barratry’ is the offense of stirring up litiga

tion.

“ (b) A ‘barrator’ is an individual, partnership, asso

ciation or corporation who or which stirs up litigation.

“ (c) ‘Stirring up litigation’ means instigating or at

tempting to instigate a person or persons to institute

a suit at law or equity.

“ (d) ‘Instigating’ means bringing it about that all

or part of the expenses of the litigation are paid by the

barrator or by a person or persons (other than the

plaintiffs) acting in concert with the barrator, unless

the instigation is justified.”