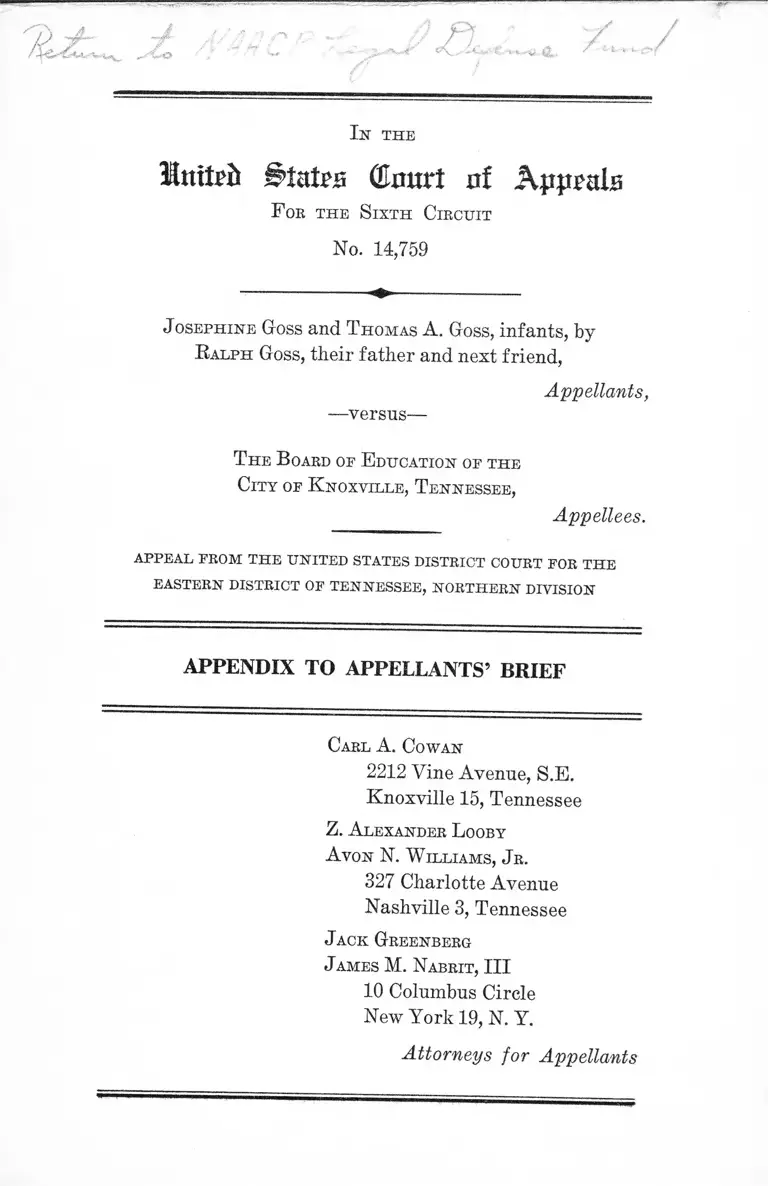

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1961. 5754acf0-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79de6e87-ada1-461a-a4ef-b4d7834f3309/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Ittttein &tnt££ (Emtrt at Appeals

F ok the S ixth Circuit

No. 14,759

J osephine Goss and T homas A. Goss, in fan ts , by

R alph Goss, th e ir fa th e r and next friend ,

—versus—

Appellants,

T h e B oard op E ducation op the

City of K noxville, T ennessee,

Appellees.

appeal prom the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NORTHERN DIVISION

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville 15, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiams, J r.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Defendant’s Vocational and Technical Training Plan

for Negro Students............................... ..................... 4a

Plaintiffs’ Objections to Plan for Vocational and Tech

nical Training ....................................... ...................... 9a

Excerpts From Hearing of June 15, 1961 .... ............. 15a

Testimony of T. N. Johnston

Direct........................... 15a

Cross .................. 27a

Opinion of the District Court Dated June 19, 1961 ...... 38a

Defendants’ Statement in Response to Court’s Opinion

of June 15, 1961 ....... ..... .......... ........... ..................... 46a

Plaintiffs’ Statement in Opposition to Defendants’

Statement in Response to Court’s Opinion of June

15, 1961 ..... 51a

Excerpts From Hearing of September 14, 1961 ....... 55a

Testimony of T. N. Johnston

Direct....... ................................... 55a

Cross .............. 67a

Redirect.................. 81a

Relevant Docket Entries ......... ....................................... la

IX

PAGE

Opinion of the District Court Dated September 20,

1961 ............................................................................. 82a

Judgment of the District Court Dated September 20,

1961 ............................................................................. 87a

Notice of Appeal Filed September 21, 1961 ..... 89a

Mnitrfr Stairs liHtrirt Court

Civil Docket 3984

J osephine Goss and T homas A, Goss, infants, by

R alph Goss, their father and next friend,

Plaintiffs,

-v.-

T h e B oard of E ducation of the

City of K noxville, T ennessee,

Defendants.

Relevant Docket Entries

1961

Mar. 31 Plan to provide vocational and technical train

ing facilities for Negro students similar to

those provided for white students at Fulton

High School, filed.

# # # # « =

Apr. 10 Specification of objections to plan filed by de

fendants to provide vocational and technical

training, etc., filed.

.y,'Tv’ w ■fr ^

June 14 Memorandum on behalf of defendants dealing

with objections of plaintiffs to the Plan filed

for vocational and technical training at Fulton

and Austin High Schools, filed.

* # # # *

2a

Relevant Docket Entries

June 15

June 19

July 14

July 27

Court approves plan submitted, with one ex

ception; Board of Education ordered to sub

mit further Plan on the exception.

-If. -V- .V. -V- -V.•if w w w *

Memorandum opinion of Robt. L. Taylor that

the Board of Education has made a good faith

effort to submit a supplemental plan that

meets the requirements of the Constitution

and that deals justly with the school children

of Knoxville, and with the sole reservation as

indicated the Court approves the plan as sub

mitted: the Court requests the Superinten

dent and the Board of Education to restudy

this one phase of the problem and try to pre

sent a plan that will meet the difficulty, if it

is a real difficulty, which the Court has tried

to point out; The Board of Education is

charged with the responsibility of operating

Pulton and Austin high schools, and this

Court will not interfere except where neces

sary to protect Constitutional rights, filed.

# * # # #

Statement filed on Behalf of Board of Educa

tion of Knoxville in Response to Court’s

Opinion of June 15, 1961, filed.

Statement filed on behalf of Plaintiffs in op

position to the statement filed on behalf of

the defendant, Board of Education of Knox

ville, in response to the Court’s Opinion of

June 15,1961, filed.

# # # #

3a

Relevant Docket Entries

Sept. 14

Sept. 20

Sept. 20

Sept. 21

Sept. 21

Plaintiffs’ motion for modification of Court’s

Judgment of June 15, 1961, heard and over

ruled by the Court.

# # # # #

Memorandum Opinion of Judge Kobert L.

Taylor, District Judge, that the plan of the

Board filed on March 31, 1961 to provide tech

nical training facilities for negro students

similar to those provided for white students

at Fulton High School is approved, and order

to be presented in conformity with the views,

filed.

# # * * #

Judgment that the plan of the Board of Edu

cation of the City of Knoxville provide Voca

tional and Technical Training facilities for

negro students similar to those provided for

white students at Fulton High School filed

March 31, 1961 is approved, and the Board of

Education is hereby ordered to put said plan

into effect; jurisdiction of the action is re

tained during the period of transition; and

to the foregoing action of the Court the plain

tiffs except.

# * * # #

Notice of Appeal by plaintiffs filed.

# * # # #

Cost Bond of Appeal filed.

*= # * # *

4a

Plan to Provide Vocational and Technical Training

Facilities for Negro Students Similar to Those

Provided for W hite Students at

Fulton High School

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POE THE E aSTEKN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

N obthebn D ivision

[ same title]

Pursuant to the judgment of the Court entered in this

cause on August 26, 1960, the defendant Board of Edu

cation of the City of Knoxville herewith attaches and files

a plan to provide vocational and technical training facili

ties for Negro students similar to those provided for white

students at Fulton High School. As shown by the Certifi

cate attached at the end of the plan, this plan has been

unanimously approved by the Knoxville City Board of

Education.

S. F bank F owlee

Attorney for Defendants

Two copies hereof and of the attached plan have been

today mailed or delivered personally to counsel for the

plaintiffs. This March 31,1961.

S. F . F owlee

Attorney for Defendants

5a

A S uggested P lan to P rovide V ocational and T echnical

T raining F acilities for Negro Students S imilar to

T hose P rovided for W hite Students at F ulton H igh

S chool

1. Continue present general policy of providing voca

tional facilities at Austin High School and at Fulton

High School when it is shown that fifteen or more

properly qualified students are interested in the

training.

2. When a course cannot be established at either Austin

High School or Fulton High School because of lack

of a sufficient number of qualified students, and the

course is already available at the other school, the

student or students may request and obtain transfer

upon the terms as set out in the transfer policy now

in effect in the Knoxville City Schools for vocational

students, same being a part of this plan.

3. When a vocational facility is not already available

at either Austin High School or Fulton High School,

but a sufficient number of qualified students are avail

able through a combination of students from the

two schools, the new facility may be established at

either school.

4. Factors to be used in deciding whether or not a new

course is established.

(a) Number of qualified students as determined by

Bulletin No. 1—“Administration of Vocational

Education,” Federal Security Agency, Office of

Education. These a re:

1. “The desire of the applicant for the voca

tional training offered:

Plan to Provide Vocational and

Technical Training Facilities

6a

2. His probable ability to benefit by the instruc

tion given; and

3. His chances of securing employment in the

occupation after he has secured the training,

or his need for training in the occupation in

which he is already employed.”

(Enrollment in vocational classes is limited

to students who have reached their four

teenth birthday.)

(b) Availability of space to take care of the maxi

mum as provided by the State Board of Voca

tional Education.

(c) Cost as determined by the Board of Education

based upon availability of funds.

5. In the continued promotion of the vocational pro

gram in the Knoxville City Schools, the Board of

Education will follow the rules and regulations as

set forth from time to time by the State Board for

Vocational Education.

6. The principals of the schools involved, the Director

of Vocational Education, and the Superintendent

acting on behalf of the Board of Education will be

responsible for carrying out this plan consistent with

sound school administration and without regard to

race.

7. This plan is to become effective at the beginning of

the school year, September, 1961.

Plan to Provide Vocational and

Technical Training Facilities

7a

T ransfer P olicy—V ocational D ivision—K noxville

City S chools— “P rocedures”

1. The student must indicate an interest in taking a

vocational course.

2. The student fills out Form #235 in triplicate at

least four weeks before the end of a school semester.

(Copy of Form #235 is attached and made a part

of this plan.)

3. The principal is responsible for seeing that at least

one standardized vocational aptitude test is given

the student and that the results are recorded on

Form #235.

4. Parents will be furnished a description of the voca

tional courses. A copy of Form #235 (the trans

ferring document) must be approved by the parents.

A statement that the student transferring intends

to remain in the new school for a period of at least

one school semester, contingent upon the student

being able to profit by the course offered, must also

be approved by the parents.

5. If the parent signs Form #235 approving the trans

fer, the principal will review the application, confer

with the attendance worker and either approve or

disapprove the transfer, writing into the record his

reason, or reasons, for disapproval.

6. The student is required to fill out Form #206 (the

official Enrollment Card), omitting only the schedule

section of said card. (Copy of Form #206 is at

tached and made a part of this plan.)

7. Forms #206 and #235, along with the student’s

cumulative card shall be sent to the Attendance

Department for endorsement.

Plan to Provide Vocational and

Technical Training Facilities

8a

8. Forms #206 and #235, along with the student’s

cumulative card, will then he forwarded to the re

ceiving principal.

9. The principal of the receiving school, after review

ing the student’s record, either accepts or rejects

the transfer, setting out in writing the reason or

reasons, for rejection.

10. An appeal from the decision of the sending princi

pal or of the receiving principal may be made to the

Superintendent by the student requesting the trans

fer. An appeal from the decision of the Superin

tendent may be made to the Board of Education.

Said appeal to the Superintendent shall be filed in

writing with the Superintendent within four weeks

after the student has received notice of the decision

of the principal from which the appeal is taken. The

appeal from the Superintendent’s decision must be

filed in writing with the secretary of the Board of

Education within two weeks after the student re

ceives notice of the Superintendent’s decision.

11. No student will be accepted at either Austin High

School or Fulton High School without following the

above transfer procedure. (The requirement in Item

# 2 above shall not apply to a new student who be

comes a legal resident of the City of Knoxville after

deadline referred to in said item.)

I hereby certify that the above plan was unanimously

approved by the Knoxville City Board of Education at a

special meeting on Thursday, March 23, 1961.

J ohn I. B uekhart M.D. B oy E. L inville

President Secretary

Plan to Provide Vocational and

Technical Training Facilities

9a

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or the E astern D istrict of T ennessee

N orthern D ivision

Specification o f Objections to Plan Filed by Defendants

to Provide Vocational and Technical Training, etc.

[ same title]

The plaintiffs, Josephine Goss, et ah, respectfully ob

ject to the plan to provide vocational and technical training

facilities for Negro students similar to those provided for

white students at Fulton High School, filed in the above

entitled cause on or about the 1st day of April, 1961, by

the defendant, Knoxville Board of Education, and, without

waiving their objections to the original plan filed in this

cause on or about 8 April, 1960, or their appeal now

pending in the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit from the decision of this Court approving

said original plan, now specify as grounds of their ob

jection to the present plan filed by defendants, the fol

lowing :

1. The plan does not provide for elimination of racial

segregation in technical and vocational training in the

public schools of Knoxville “with all deliberate speed”

as required by the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2. The plan does not take into account the period of

nearly seven (7) years which have elapsed during which

the defendant, Knoxville Board of Education, has com

10a

pletely failed and refused, either in its technical arid

vocational schools or any of its other schools, to comply

with the said requirements of the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States; except for the limited

desegregation in the first grade, approved and ordered

by this Court in August, 1960.

3. The plan affords no relief to any of the plaintiffs,

or the class they represent in this cause, who are or may

be above the first grade in school, against defendants’

policy and practice of racial segregation in the public

technical and vocational schools of Knoxville, unless the

particular course of training they seek is either: (a) al

ready available at either, but not both, the Negro or the

White High School, and cannot be established, on a racially

segregated basis, at the other school because of lack of

sufficient qualified students of the same race or color; or

(b) is not available at either the Negro or White High

School, and is sought by less than a sufficient number of

qualified students of either race to permit establishment

of same, on a racially segregated basis, at both the Negro

and White High School. This deliberate continuance by

defendants of their policy and practice of racial segrega

tion in technical and vocational training, except for said

narrow and restricted exceptions based on absolute ne

cessity, for an additional period of eleven (11) years, is

not “necessary in the public interest” and is not “con

sistent with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date” in accordance with the said requirement of the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Specification of Objections to Plan to

Provide Vocational and Technical Training

11a

4. The defendants have not carried their burden of

showing any problems related to public school administra

tion arising from:

a. “the physical condition of the school plant” ;

b. “the school transportation system” ;

c. “personnel” ;

d. “revision of school districts and attendance areas

into compact units to achieve a system of deter

mining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis” ;

e. “revision of local laws and regulations which may be

necessary in solving the foregoing problems” ;

as specified by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of

Education (May 31, 1955), 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 653, which necessitate the additional time con

templated by their plan, in regard to technical and voca

tional training, for compliance with the constitutional re

quirement of a racially unsegregated public educational

system.

5. The plan forever deprives the infant plaintiffs and

all other Negro children now enrolled in the public schools

of Knoxville above the first grade, of their rights to a

racially unsegregated public education in technical and

vocational subjects, except for the narrow and restricted

exceptions mentioned hereinabove, and for this reason

violates the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Specification of Objections to Plan to

Provide Vocational and Technical Training

12a

6. The plan, as well as said original plan approved by

the Court, fails to take into account the rights of the infant

plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly situated and

forever deprives them of their rights to enroll in and

attend summer courses, special education classes and

schools, and other forms of special education above the

first grade, which are not classified as technical and voca

tional schools or training, and as to which enrollment is

not based on location of residence.

7. Insofar as the plan incorporates by reference, or

contemplates the use of, the transfer provisions contained

in Paragraph six (6) of the said original plan approved

by this Court, the same violates the due process and equal

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States in that said paragraph

provides racial factors as valid conditions to support

requests for transfer, and further in that the racial factors

therein provided are manifestly designed and necessarily

operate to perpetuate racial segregation.

8. Paragraph four (4) of the plan authorizes the de

fendants, in determining whether a student is a qualified

student within the meaning of the plan, to utilize vague

and subjective criteria or factors, with no safeguard pro

vided against defendants’ past policy and practice of racial

discrimination; and also permits defendants to use for

this purpose criteria or factors which are closely related

to racial discrimination and segregation in job opportunities

in the community; in violation of the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

Specification of Objections to Plan to

Provide Vocational and Technical Training

13a

9. The plan establishes an elaborate and burdensome

“Transfer Policy” or procedure for vocational and tech

nical training, which has not been applicable to those

students already registered and enrolled in such courses

at Austin High School and Fulton High School on a

racially segregated basis; but does apply to plaintiffs and

all others similarly situated who now seek to enroll in

said courses, and without any safeguards against racially

discriminatory application against plaintiffs and the class

they represent; thereby placing unwarranted burdens and

restrictions upon plaintiffs and those similarly situated,

in obtaining even the narrow and restricted relief afforded

them under the plan, solely because plaintiffs seek a

desegregated education. Said burdens are not borne by

children now and heretofore enrolled in said courses on a

segregated basis. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated

are thereby deprived of due process of law and the equal

protection of the laws, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Wherefore, the Plaintiffs j)ray:

That the said plan now proposed by defendants relating

to vocational and technical training be disapproved, and

that the injunctive relief prayed for in the Complaint be

granted as to all technical and vocational schools or courses,

summer courses and educational training of a specialized

nature as to which enrollment is not based on location of

residence, in the public school system of Knoxville, said

injunctive relief to be effective not later than the beginning

of the Fall Semester or Term of the City Schools of Knox

ville in September, 1961 as to any courses which are not

Specification of Objections to Plan to

Provide Vocational and Technical Training

14a

carried during the summer, and not later than the be

ginning of the Summer Term, 1961 as to summer courses.

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S. E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lexander L ooby and

A von N. W illiams, J r .

327 Charlotte Av.

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood Marshall and

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Copy of the foregoing Specification of Objections has

been either mailed or delivered to the office of S. Frank

Fowler, Esq., Attorney for Defendants, Hamilton National

Bank Building, Knoxville, Tennessee, this the ...... day of

April, 1961.

Specification of Objections to Plan to

Provide Vocational and Technical Training

15a

Excerpts From Hearing o f June 1 5 ,1 9 6 1

4̂ ^ ^

T. N. J ohnston, a witness on behalf of the defendants,

after having been first duly sworn, was examined and testi

fied as follows:

Mr. Fowler: We will just put him on to answer

any question.

The Court: I wish you would take, in a general

way, each paragraph of this plan and let him ex

plain it to me in school language.

Before doing that, I would like to know how many

students are in the vocational school at Austin, and

what they study generally, and how many are in the

vocational school at Fulton, and what they study

generally, and what is the difference between the

two schools, if any, and how this plan affects the

students in each school separately and combined.

Remember, that you gentlemen on both sides have

— 10—

grown up with this supplemental plan and the Court

knows nothing about it except what it has learned

from reading the plan itself and the objections and

the briefs in response to the objections, and I would

like to get the picture a little better in my mind.

Direct Examination by Mr. Fowler:

Q. Mr. Johnston, please state how many students in the

vocational educational program there are at Fulton High

School as of the close of last school year last month, and

the same thing for Austin High School. A. At the close of

the school year, there were, out of an enrollment of 1300—

—9—

16a

that is in round numbers—at Fulton High School, there

were 500 vocational students, or approximately 40 percent

of the total enrollment.

At Austin High School, out of an enrollment of a little

better than 600, there were 355 in some phase of voca

tional work, or approximately 53 percent of the total enroll

ment.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

The Court: What was the percentage at Fulton?

The Witness: 40 percent and 53 percent at Austin.

— 11—

The Court: All right.

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. Now the Court indicated a desire for some informa

tion, I think, comparing the respective—the scope of the

respective education, the one at Fulton High School and

the one at Austin High School.

Mr. Fowler: That may be, by way of reminding

his Honor, of some reference that was in the last

time. I think the reason for this special supple

mental plan is because Austin was deficient.

The Court: I just want a thumbnail description

of the schools. I know you went into that in detail

at the other hearing.

A. At Austin High School there are nine courses offered

in the vocational field, and at Fulton High School there

are fifteen courses offered in the vocational field.

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. What courses were offered at Fulton that were not

offered at Austin? A. Machine shop, which is one, sheet

metal work, radio, television, printing—

17a

The Court: What was the last one ?

A. (Continuing) Television, repair and maintenance, print

ing, drafting—

—12—

The Court: Printing?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: All right. What was the next one?

A. (Continuing) Drafting, commercial photography, com

mercial art, electricity, refrigeration and air conditioning,

and distributive education.

Q. What courses were offered at Austin that were not

offered at Fulton? A. Brick masonry, shoe repair, tailor

ing, and industrial electricity. That is all.

Q. Mr. Johnston, will you explain, as simply as possible,

how, under the plan now under investigation, equal oppor

tunity is accorded Negroes with whites in vocational and

technical education in these two schools. And if you want

to, you may take the Plan One and go through it paragraph

by paragraph, and so that the record may be complete,

read each paragraph before discussing it. A. May I give

you a summary? I ’ve tried to reduce this to actually three

main points.

Q. Yes, sir. A. The total plan, then I can go back and

take each item in the plan.

Q. Whatever will give us the meaning as it really is,

—13—

unencumbered by words. A. All right. The first basic

point, in my opinion, is this. If a course is available at

Austin, Negro students will continue to attend Austin. If

the course is available at Fulton, white students will go

to Fulton for the course.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

18a

No. 2. If a Negro student wants a vocational or tech

nical course that is not available at Austin but is available

at Fulton, the Negro student may request and obtain the

course at Fulton under the terms of the transfer policy.

The white student may do the same under similar cir

cumstances.

No. 3. A course which is not being offered at either

Austin or Fulton is desired by a few Negroes and a few

white students, when that situation exists, then a course

may be established at either school for the benefit of both

white and Negro students.

I think those three points are basic to the plan and in

brief pretty well spell out the plan.

Now, in No. 1, in our suggested plan here, “Continue

present general policy of providing vocational facilities

at Austin High School and at Fulton High School when it

is shown that 15 or more properly qualified students are

interested in the training.”

That is the policy which the Board of Education has

—14—

followed for years and years. If there were a sufficient num

ber of qualified students at Austin High School, they had

the space available, the Board would set up the course for

them.

If there were a sufficient number of students at Fulton

and they had the space, they would set up the course.

That is the general policy they have followed.

Q. Let me ask you this. If this plan is approved and

goes in effect in September, if a student now attending

Austin High School and there studying a vocational or

technical subject which is also available at Fulton, desires

to transfer to Fulton, will that transfer be granted and

what will be the handling of that!

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

19a

I am talking about where you have got the present situa

tion of students already in Austin and got a student body

already at Fulton too. A. I will give an example which

may better illustrate this.

They have auto mechanics at Austin. They have auto

mechanics at Fulton. Now if there are a sufficient number

of students to maintain the course at Austin, they would

continue to go to school at Austin.

Q. Is that because of a racial condition or fact, or is it

—15—

because they are already in school? A. They are already

in the school—

Mr. Williams: We object to leading questions, if

your Honor please.

Mr. Fowler: It is hard to lead this man, Mr.

Williams.

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, the more

intelligent the witness, the more easily he is led, I

would say.

A. This follows the general policy that the Board has been

following. The students are there, the equipment is there,

a sufficient number of qualified students, and there is where

they go to school.

In the auto mechanics program at Fulton High School,

if there is a sufficient number of students, the equipment

is already there, that is where they go to school.

Now if the capacity of the facilities at Austin High

School should not be adequate for the number of Negro

students qualified to take auto mechanics at Austin High

School and there is space available at Fulton, those stu

dents may transfer to Fulton and take up the space there.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

20a

And similarly, if they are crowded at Fulton, and there

are five or six spaces available at Austin High School,

—16—

the white student may apply to transfer to Austin to take

up the space.

Q. All right. Proceed. A. Now then, No. 2: “When a

course cannot be established at either Austin High School

or Fulton High School because of lack of a sufficient num

ber of qualified students and the course is already avail

able at the other school, the student or students may re

quest and obtain transfer upon the terms as set out in the

transfer policy now in effect in the Knoxville City schools

for vocational students, said being a part of this plan.”

That is basic. If the course is established at Austin,

already operating, it is not at Fulton, there is room at

Austin, there are four or five white students properly

qualified, they may request transfer to go over and take

the work at Austin, and the same would work going back

toward Fulton.

If the course is already going at Fulton and it is not at

Austin and Austin has some qualified students and they

desire this program, they may transfer to Fulton High

School to take the course.

No. 3 in the plan: “When a vocational facility is not

already available at either Austin High School or Fulton

High School but a sufficient number of qualified students

are available through a combination of students from the

- 1 7 -

two schools, the new facilities may be established at either

school.”

Now to me that simply means this: That we might have

seven or eight or nine Negro students who desire a par

ticular course. We may have seven or eight white stu

dents who desire the same course.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

21a

We would not be justified in setting up a course at Aus

tin for seven or eight students and going over to Fulton

and setting up another course for seven or eight students,

so we could combine those two and set it up at Austin or

at Fulton wherever we had the space and the facilities.

Q. What is the next ground there? A. No. 4: “Factor

to be used in deciding whether or not a new course is estab

lished.”

The first part: “The number of qualified students as

determined by Bulletin No. 1.”

And that Bulletin No. 1 is a little bulletin that is put

out by the Federal Security Agency, Office of Education,

entitled “Administration of Vocational Education,” and it

is sort of the Bible of vocational education for the United

States, and our State Department follows this very closely

and it is passed on to us here in the local community, and

we must follow the minimum standards set out in this

bulletin in order to get the funds from the State and Fed-

—18—

eral Government on a reimbursable basis which runs 50

percent up to 75 percent reimbursable, matching funds.

As I said, “the number of qualified students as deter

mined by Bulletin No. 1”—what are these items?

First: “The desire of the applicant for the vocational

training offered.”

It has been more or less standard for years and years

in this country as being No. 1—there must be the desire on

the part of the student to enter into a program of voca

tional training.

No. 2: “His probable ability to benefit from the instruc

tion given.”

The theory being that it is a waste of the student’s time

and of your facilities and money if there is no probability

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

22a

that the student can benefit or profit by the instruction

ottered. That is No. 2.

No. 3: “His chances of securing employment in the occu

pation after he has secured the training, or his need for

training in the occupation in which he is already employed.”

I should point out that for many years the Vocational

Division of the State Department of Education advocated

that courses set up on a vocational basis should be done

—19—-

so as to meet the needs of the local community. That is, the

employment needs. If we set up a course in auto mechanics

or television, or in some particular field, then there should

be a chance to absorb those people in our community, jobs

locally, and that has been characteristic in all plans for

vocational education, as I say, throughout the United

States. We don’t limit that to the local community because

communications and transportation has brought us all

closer together throughout the country and as long as we

feel there are employment opportunities anywhere in a

field, we feel justified if the sufficient number of students

are interested.

We may find a student in a particular field and he will

get a good job in Toledo, Ohio, or Los Angeles, California.

Of course, again we would train them particularly within

the needs of our local community.

I would like to point out, too, that under the vocational

program, students to be eligible must be at least 14 years

of age or over.

Now some other factors that would determine the estab

lishment of a course—that is, new courses.

“Availability of space to take care of the maximum as

provided by the State Board of Vocational Education.”

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

23a

I would like to explain that the State Board of Voca-

—20—

tional Education and the administration of the policies

set by that Board have to be very carefully followed by a

local school system developing a vocational program in

order to get funds.

Now in occupations or in vocations that are somewhat

dangerous and hazardous, they set a limit on the number

of students that one instructor can properly handle and

supervise without them getting hurt. One of those shops

is electricity, and the limit is 22. Machine shop is another

one and the limit is 22—feeling that one teacher does a

pretty good job if he can look after 22 students with all of

that dangerous equipment without some of them getting

hurt.

By the Court:

Q. Is there any available space at Fulton now? A. No,

sir.

Q. Is there any available space at Austin? A. No, sir.

That comes and goes, your Honor, with the enrollments. I

say at the moment, no.

In 90 days or six months there may be a little shift and

one course may be out completely because of an insuffi

cient number of students, and in that case, we can intro

duce a new course that students may desire, either at

Austin or at Fulton.

Q. What I mean, you say there are 1400—1300 students

—21—

at Fulton? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, how many—as an example, one of the schools

in the East—I think it is Vassar—three or four years ago,

they had applications, at least they said they did, and a

new educator there and they were getting hard to deal with,

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

24a

turning these students away because they could get others,

but when I went to school it was just a question of paying

tuition, but now you have to be a double-A student—at least

it has been my experience with my children—a double-A

student, and you have to have tuition and you have to have

all those things. Now Vassar, I believe, three years ago,

maybe four years ago, the president allegedly stated, in

substance, to a person in Louisville, that they had space,

available space, for 400 freshmen and they had had 1400

applicants.

What I am trying to get is, do you have any available

space left out at Fulton for any additional students, or

do you have any available space left at Austin? A. Fulton

High School was built to accommodate a maximum of 1500

students, and there are actually two divisions of the school.

The shop division and the general or academic division.

We think of the school as all one school, try to treat the

—22—

children as though they are one, but we do have these

shops, and there is no available space to create new shops

in that building. We can crowd in some other students in

the general classes throughout the school up to 1500.

Q. Am I correct in the understanding that at present

there is no available space for additional students either

at Austin or Fulton? A. No. I am thinking about the

physical—

Q. I am too. A. —space occupied by the shops.

Q. I am too. A. I have no way at this moment of tell

ing how many students will be involved in the shop sec

tion at Fulton in September, the day after Labor Hay, nor

at Austin.

I would assume that if the last year holds up this year,

there would be a little space in four or five of the shops.

In other words, we could take a few more students.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

25a

Q. At the maximum number, what would you say? A.

Possibly 40 or 50.

Q. In each school? A. Yes, sir.

Q. That is what I wanted to know. A. I don’t have the

—2 3 -

figures, the breakdown, and these shop classes are normally

organized during the summer based on the applications

from the students so we will know what kind of shop pro

gram to plan for September, so I must give you an ap

proximate figure.

The Court: All right.

A. (Continuing) And then the next item, of course, would

be “cost as determined by the Board of Education based

upon availability of funds.”

By Mr. Fowler:

Q. That has no racial significance. If it hasn’t racial

significance perhaps the Court is not interested in it. A.

This applies to both schools.

No. 5: “In the continued promotion of the vocational

program in the Knoxville City schools, the Board of Educa

tion will follow the rules and regulations as set forth from

time to time by the State Board of Vocational Education.”

They change regulations occasionally, but that would

have nothing to do with race. It would apply equally re

gardless of race, but we must follow those if we are to

expect funds from the State.

No. 6: “The principals of the schools involved, the Direc

tor of Vocational Education, and the Superintendent act-

—24—

ing on behalf of the Board of Education will be responsible

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

26a

for carrying out this plan consistent with sound school ad

ministration and without regard to race.”

No. 7: “This plan is to become effective at the beginning

of the school year, September, 1961.”

The rest of this is the method of transferring students.

Shall I go over that ?

Q. Mr. Johnston, I don’t think that it will help us unless

there is something in there that is capable of being inter

preted in a double way or misinterpreted to prejudice

Negroes.

Is there any difference between these transfer provisions

here as stated in this supplemental plan and as you have

applied them in the past? A. No, sir. We use the same

transfer cards we have used for the past ten years.

Q. Those are Forms 206 and 235? A. That is correct.

Q. They are both under one transfer policy? A. That

is right. This one here we used as an exhibit, it says,

“Knoxville Public Schools, Knoxville, Tennessee, Applica

tion for Transfer to the Vocational Division of Fulton High

School.”

Q. You are going to probably amend that to put in Ful-

_ 2 5 -

ton and Austin? A. Yes. We had a supply on hand.

We saw no need to reprint that immediately, but it will

be changed to apply to both because we have been using

it for ten years.

This is a normal enrollment card that every high school

student uses in the spring to fill out what he would like

to take next September. Been using it for 20 years.

Q. In the light of your remark just made about the

transfer policy and Forms 206 and 235 and in the absence

of any specific criticism in the objections filed of the lan

guage of the transfer policy or those forms, I think maybe

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Direct

27a

I should just ask you one or two questions generally to

get to the heart of whether any discrimination is going to

occur.

There is one question I asked you in conference the other

day, Mr. Johnston. Suppose that a Negro student located

close, we will say, to Fulton High School desires to take

a vocational or technical course and applies to Fulton High

School. If he is otherwise qualified, will he be accepted

there? A. Yes, but he is first obligated to check with

his principal at Austin.

The Court: Wait just a minute. Read that ques-

—26—

tion again.

(The question was read by the reporter.)

A. (Continuing) He won’t be accepted until he has cleared

with the school to which he would normally belong, which

is Austin High School. That is the one school that reaches

out all the way to the City limits. That is the school he

would normally attend, and the principal is responsible for

knowing where the student is, and he simply clears with

his principal and that is all he has to do.

He would be accepted, but the record would have to be

cleared through the principal of Austin High School so

he knows where his student is. He is at Fulton.

The same would apply to a white student.

Mr. Fowler: Your Honor, I have no further ques

tions.

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. Mr. Johnston, in your answer to that question, why

did you indicate that a Negro student would be required

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

28a

to clear with the principal of the school at which he would

normally belong, and you mentioned Austin? A. In this—

Q. Why would he normally belong at Austin? A. Well,

there is one senior high school in this City for Negro high

—2 7 -

school students.

Q. So that your answer to that question is he would

normally belong to Austin because he is a Negro and

Austin is still a segregated Negro high school; that is

correct, isn’t it? A. I am just repeating what I said, that

this City has one modern, up-to-date Negro high school

for high school students. The zone extends to the City

limits. The principal must know where his students are.

Q. Yes, sir, and that is true both as to academic and

vocational education pursuits for Negro children in Nash

ville—Knoxville? A. The Austin High School has gen

eral education courses and vocational courses for Negro

high school students.

Q. There are no white students at Austin, are there? A.

Not that I know of.

Q. Austin then still is a segregated school; a segregated

Negro school; that is true, is it not? A. That is right. It

is as of now. Yes, sir.

Q. And except for the single possibility that there may

be some instance where a particular white student wants

to take tailoring and you don’t have 15 students who want

tailoring out at Fulton, except for that type of situation

—28—

Austin will remain a segregated Negro high school, will it

not? A. Possible.

Q. Well, isn’t that true as a matter of fact under your

plan, sir? A. Well, if no white students apply to take a

course there that is not given at Fulton, then it would

still be all Negro students in Austin.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

29a

Q. No, sir, I don’t believe I am making myself clear,

Mr. Johnston.

I stated that except for the single instance which you

have explained to the Court, where there may be some

white student who wants a course that is not offered at

Fulton and for some reason it isn’t offered at Austin either

and there aren’t enough of them to make up segregated

courses at the two schools, or there aren’t enough students

at Fulton to make up a segregated course, except for that

situation Austin, under your plan, will remain a segregated

high school both as to its academic and its vocational

aspect; that is true? A. I think that is true.

Q. And so, then, your plan does not contemplate, as able

counsel has expressed it, the immediate total elimination

of segregation in vocational high schools in the two voca

tional schools beginning next fall; it does not contemplate

—29—

that? A. Complete?

Q. Yes, sir. The immediate total desegregation of Fulton

and Austin High Schools come next fall? A. Not com

plete and total.

Q. And, as a matter of fact, the only integration that

this plan does contemplate is a situation where you just

can’t possibly, by reason of the fact that there aren’t

enough students to do it, set up segregated courses at both

schools; that is true, is it not? A. No, sir.

Q. Well, will you explain how under any other circum

stances under this plan any integration at all could occur

in Austin or Fulton? A. We have been asked to provide

facilities for the Negro students that are now being given

at Fulton that are not being given at Austin. And we

have worked out a plan to make it work both ways.

White students may take a course at Austin if it is not

given at Fulton and vice versa.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

30a

Q. And that is the only situation, that is the only situa

tion where this plan contemplates any integration at all

where—incidentally, there is one additional factor—it isn’t

just where a course is offered, but where the course can

not be established at Fulton for want of a sufficient number

—30—

of students, isn’t it; isn’t that true under your plan? A.

No.

Q. Sir? A. I don’t agree. There is the possibility of a

combination of students between the two schools and the

course may be established at either.

Q. Sir? A. The plan provides for courses to be estab

lished at either Austin or Fulton if through a combination

of white students and Negro students there are a sufficient

number.

Q. That is correct, but if there are enough white students

to establish a course at Fulton, then a white student will

stay at Fulton, won’t he? A. That is correct.

Q. And if there are enough Negro students to establish

a course at Austin, then the Negro student will remain

at Austin? A. That is the general policy.

Q. And he does not have any right to transfer under

this plan? A. He can transfer if he can’t get a course

at Austin and he can get it at Fulton.

Q. Yes, sir, but he would not have—he first has to estab-

—31—

lish that there are not 15 students who want that same

course at Austin before he becomes eligible to transfer

to Fulton; is that correct? A. I would say so.

* * * * *

—33—

* * * * *

Q. I see I am not making myself clear, Mr. Johnston.

I am assuming that the requisite number apply at Austin,

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

31a

that 15 apply so that you will proceed to set up a course

at Austin. A Negro student who wants to take a course

which is available at both Austin and Fulton next fall,

would not be eligible to apply at Fulton, would he! A.

If we have a sufficient number at Austin in the course?

Q. Yes, sir. A. That is correct.

Q. And, moreover, if you do not have the course at

Austin at the present time and you have it at Fulton, then

this Negro student who wants to take the course must

first ascertain by some means or other that you cannot set

up the course—that you cannot find 14 other Negro students

to set up the course at Austin before he will be eligible

under your transfer procedure to apply over at Fulton;

that is correct also, is it not? A. You say the student

would have to ascertain ?

Q. Well, he would, either lie—he would have to ascer

tain himself or whether he would just have to wait while

—34—

the Board ascertained it, he— A. I think—

Q. Pardon me? A. That is somewhat of a reflection on

the people that we have to administer the schools.

Q. I assure you I did not intend— A. We will know

whether or not we will be able to establish a course here

or there a little ahead of time. We will not put any student

to any great disadvantage because, and it may surprise

you, but we are interested in students regardless of race.

Q. That does not surprise me at all. But, Mr. Johnston,

whether he would have to wait or not, he could not apply to

Fulton if the Board could find 15 Negro students to create

a new course at Austin? A. That is correct. But you

are implying that we would deliberately search around

and try to find 15 students.

Q. No, sir. All I am simply trying to establish, and I

am trying to establish this because for some reason I

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

32a

apparently did not make myself clear to you, except in

these two narrow instances where the course is available

at Fulton and is not available at Austin, or in the other

instance where the course is not available at either place

and there are an insufficient number of students to estab-

—35—

lish it on a segregated basis at both places, and the Board

might decide to establish it at Fulton rather than Austin,

except in these two instances the Board, under this plan,

does continue its policy of segregated education—racially

segregated education in the vocational schools; am I mak

ing myself clear, Mr. Johnston? A. Yes, but you are try

ing to get me to say something that I am not going to say.

Q. Well,— A. The Board of Education is proposing to

follow its general policy but it is now going to be applied

to all the students, without regard to race.

Q. Now will you explain what you mean by that in terms

of abolition of segregation in the vocational schools? A.

We were requested, Mr. Williams, to make facilities avail

able for these students that we had at Fulton and did not

have at Austin and vice versa. We propose to do that.

Q. So that under this plan the Board does not even pro

pose to be eliminating segregation in the vocational schools

except as it proposes in these narrow restricted instances

that are set forth in paragraph 2 to provide facilities for

Negroes or whites where it is physically impossible to set

—3 6 -

up segregated facilities. That is true, isn’t it, Mr. John

ston? A. I don’t think it is a narrow situation.

Q. Except for my discussion of the two factors set

forth in paragraph 2, that is true, is it not? The Board

—what I am saying, the Board is not attempting here to

eliminate segregation in the two vocational high schools?

A. Well, not completely.

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

33a

The Court: I will let you ask him.

Q. No, sir, except for the instances that you set forth

in paragraph 2 of your plan, segregation will remain in

the vocational high schools, compulsory racial segrega

tion? A. I don’t agree.

Q. Well, in what respect will it not remain?

Mr. Fowler: Your Honor, isn’t this sort of a

re-asking? We can argue between counsel and it

may go on forever.

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, I am sort

of like the Court, I would like to know exactly what

the Board means by this plan.

A. Under this plan, the Board of Education intends to

make available facilities that are in existence at Fulton

High School that are not now in existence at Austin, and

- 3 7 -

vice versa.

By Mr. Williams:

Q. In the fashion that is set forth in paragraph 2 of your

plan? A. Well, as set forth in this plan.

Q. Will you explain to me what is meant by paragraph

1 of the plan. A. “Continue present general policy of pro

viding vocational facilities at Austin High School and at

Fulton High School when it is shown that 15 or more

properly qualified students are interested in the training.”

Q. Has that general policy in the past had race involved

as a factor? A. In the past?

Q. Yes, sir. A. If we had in the past 15—as a matter of

fact, it used to be 10 under the State regulations—if we

had the sufficient number of students at Austin High School

interested in courses, and if there were at all possible space,

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

34a

money, and so forth, available, the coarse was set np. The

same thing was done for the white students.

Q. Then that policy has had, necessarily as a factor in

that part of these schools, segregated schools, one for

Negro and one for white? A. Austin High School is the

normal high school that serves the City for Negroes.

—38—

Q. Exclusively for Negro and Fulton for white? A.

Yes.

Q. And then under paragraph 1 you intend to continue

that? A. Well, it says continue the present general policy.

It is pretty plain.

if1 ̂ ̂ ̂ ^

—41—

Q. Of the 500 that you estimate over at Fulton, how many

of those are already enrolled in past years? In other words,

how many of those were in school as of last year?

Did I understand you to say that as of school in Sep

tember about 500 students? A. I didn’t say that.

Q. You don’t know how many you expect over there?

A. If I left the impression that I knew, that was a wrong

impression. I didn’t intend that.

I have no way of knowing. I can only estimate.

I would say that last year we had 500 students in the

vocational division of Fulton, or 40 percent of the total of

around 1300.

Q. But your estimate is based on initially accepting and

assigning white students to Fulton and assigning Negro

students to Austin; that is correct, is it not? A. That is

all we have had to go by. This plan has not been in effect

yet. How else could we do it?

Q. Well, I won’t argue that point, but that is your inten

tion under this plan? A. Under this plan, we are simply

—4 2 -

asking students to let us know their intentions four weeks

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

35a

before the end of a school semester, which we have been

asking students to do that on a segregated basis for ten

years, to my personal knowledge, and that helps us to

organize the shop program.

Q. Yes, sir. A. I might explain to you, and you can

cut me off, if you think it would not be helpful, but we

have to enter into a contract, sign a contract with the

State Department for Vocational Education for the shops

which we propose to operate for the school year coming

up, say, 1961-62, so that the State can figure out how much

money they are going to have to figure on giving us.

We start planning this always in the spring, and we work

on it some during the summer. We follow up the appli

cants to see if they change their minds, to see if they are

really wanting to go into it, to see if they are really quali

fied, so that when we do sign a contract that we will operate

a certain number of shop courses, that we will have a

minimum number of changes after school starts.

Q. But now, of course, you have already received your

applications for the school from the white students four

months before the end of this— A. Four weeks.

Q. You have already received those, have you not? A.

- 4 3 -

Yes. I don’t know how many, I haven’t cheeked. But that

has been a usual custom.

Q. And you, I think, propose to allow a Negro student

who wants to apply for these courses to apply within two

weeks of next school term; is that correct! A. Since school

is already out and it would be physically impossible for

a student to apply four weeks before the end of the term,

we think under the circumstances that if we are given two

weeks, we could plan and go ahead with this.

Q. Now you stated that most of these courses are rea

sonably skilled and technical. Some of them are actually

highly skilled and specialized, are they not, such as elec-

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

36a

ironies? A. Yes, if you want to give specimens I will

agree with you. Yes, sir.

Q. And I believe for that reason it was limited to 22

students; that is correct, is it not? A. There are limita

tions, that is right, on various courses.

Q. Suppose for the moment, that course is filled up

with white students who applied last spring, and then some

Negro student comes in and wants the same course, he

can’t get, or you can’t find, 15 Negro students at Austin

—44—

who want it, what is going to happen to him? A. We

might have enough students left over to take that student

and start a new course.

Q. But if you don’t, then what is going to happen to

him? A. I don’t know. We can cross that bridge when we

get to it.

Q. You would not be prepared to state at this point

you would go back and put him at the head of this list in

the spring, would you, sir? A. We have always operated

on a first come, first served basis.

Q. Yes, sir, so that he would be on the tail end of the

list? A. Not necessarily. There might be circumstances

that would cause us to fit the student in the course.

* # # # *

—47—

* * # * *

Q. You don’t deny that there are present inequities in

the programming at the two institutions? A. We have

inequities in programs within the Fulton High School;

—48—

we have inequities at Austin, and every other high school

we have.

Q. I think you would agree that a substantial inequity

exists regarding the 11 courses that are offered at the

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

37a

white school and not offered at the Negro high school?

A. Well, isn’t there a difference in the enrollments, 500

against 355 ?

# * # # *

—68—

# # * # #

Q. Even where you have got the same courses at both

schools, you have got plenty of Negro students living out

in the Fulton area who come right by Fulton High School

and come all the way over to Austin? A. What do you

mean by plenty?

Q. You have quite a few. A. Only 27 children live out

in this section and Chicamauga—the northwest section,

let’s call it.

Q. Mr. Johnston, regardless of a white child’s place of

residence, he can g-o to Fulton; that is true, isn’t it? A.

Regardless of his residence?

Q. Regardless of the place of residence, he can go to

Fulton? A. If he lives within the corporate limits and he

qualifies, he can be transferred to Fulton.

Q. Regardless of a Negro child’s residence, he cannot

go to Fulton unless he falls within paragraph 2 of this

—6 9 -

plan? A. That is his school.

Q. That is his school because he is a Negro; that is true,

is it not? A. Well, you can say that. I don’t care to say

that.

Q. You would not deny the truth of what I stated? A.

Austin High School is the senior high school for Negro

children.

Q. Because he is a Negro? A. Austin High School is

the high school that serves the Negro high school students

in the City of Knoxville.

# * * * *

T. N. Johnston—for Defendants—Cross

38a

Opinion Dated June 19, 1961

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the E asteen D isteict of T ennessee

N oetheen D ivision

[ same title]

Opinion as R endeeed F eom the B ench

The Court filed a written memorandum opinion in this

case on August 19, 1960 after hearing two or three days

of evidence. That hearing involved a plan for desegrega

tion, submitted by the Board of Education which the Court

approved with the single reservation that pertained to the

vocational section of the Fulton High School.

In that opinion, the Court said in part:

“In his deposition, Superintendent Johnston was

asked about the industrial courses given at Austin

High School, the colored school, and at Fulton High

School, the white technical school. It appeared from

his testimony that Fulton High gives a course in tele

vision, a course in advanced electronics, some in air

conditioning, refrigeration, commercial art, commer

cial photography, distributive education, drafting,

machine shop, printing and sheet metal which are not

offered at Austin High School. Certain courses, he

testified, such as brick masonry, tailoring, etc., are

offered at Austin which are not offered at Fulton.

“Colored students are not admitted to these courses

at the present time at Fulton High School because of

the segregated schools.

“Generally, the testimony of Superintendent John

ston was that the school facilities and teaching level

39a

at both the colored and white schools are equal. He

pointed out that the colored teachers are paid at the

same salary level as those in the white schools and

that the work done is equivalent. These facts were

also stipulated.

“The conclusion the Court draws from this evidence

is that students including plaintiffs now in school who

would not, if Plan Nine were adopted, be permitted to

go to an integrated school, would still have equal op

portunities for an education in the line colored schools

with their excellent teaching staffs.

“This conclusion is not true of the special technical

courses offered at the Pulton High School. Under Plan

Nine colored students now in school and desiring these

courses would be barred from taking these courses.

They would have to complete their scholastic education

without the opportunity of taking these courses. Super

intendent Johnston testified that he had talked to the

teachers in the Fulton High School and they were of

the opinion that to admit colored students to these

courses would cause trouble and disciplinary prob

lems, an opinion in which he joined.

“Nevertheless, the Court feels that despite the great

merit of Plan Nine, it is deficient in that it precludes

colored students now in school from ever participating

in these specialized courses.” (Pages 15 and 16.)

Again: “The Court finds that the Plan submitted by

the Board is not only supported by the preponderance

of the evidence, but by all of the evidence, with one

exception. With reference to the technical courses

offered in the Fulton High School to which colored

students have no access, it directs that the defendants

in this cause restudy the problem there presented and

Opinion Bated June 19,1961

40a

present a plan within a reasonable time which will

give the colored students who desire those technical

courses an opportunity to take them.” (Page 19.)

The Board of Education submitted a plan for Fulton

vocational high school on March 31, 1961, in response to

the direction of the Court. It is stated by the Board through

its counsel that this plan in the main continues vocational

and technical courses at both Fulton and Austin high

schools, and provides unimpeded transfers where a course

is provided at only one school, maintains the present

courses, establishes new courses when 15 or more students

want them whether they be white or black or mixed, sets

up criteria for the establishment of new courses, which

criteria are not related to race, and, finally, expressly for

bids racial discrimination.

Plaintiffs have filed objections to the plan consisting of

nine separate paragraphs.

In the first paragraph it is stated that the plan does not

eliminate segregation in vocational and technical training.

It is the insistence of the Board that the plan does elimi

nate segregation. This paragraph provides that the gen

eral policy at Austin High and Fulton High of providing

vocational facilities when 15 or more properly qualified

students are interested shall continue.

The second paragraph provides that either Austin High

or Fulton High, lacking a sufficient number of qualified

students for a course and the course is available at one or

the other schools, student or students may request and

obtain transfers upon the terms as set out in the transfer

policy now in effect in the Knoxville schools for vocational

students, the same being part of this plan.

Plaintiffs say that this plan fails to take into account

the delay of nearly seven years which has occurred since

Opinion D ated June 19,1961

41a

the Brown decision. Defendants’ answer to this contention

is that the plan is effective September 1961 and the objec

tion is without substance.

Paragraph three provides that when a vocational facility

is not already available at either Austin High School or

Fulton High School, but a sufficient number of qualified

students are available through a combination of students

from the two schools, the new facility may be established

at either school.

Plaintiffs assert that this paragraph continues segrega

tion in effect except in the two instances indicated in this

paragraph and paragraph two. In response to this objec

tion, the defendants say that the plan is broadly phrased

and contains no language whatever having the limited effect

which plaintiffs claim result from the language of the plan;

moreover, the plan expressly forbids racial discrimination.

Paragraph four deals with the factors to be used in

deciding whether or not a new course is established.

In response to this paragraph, plaintiffs say that the

Supreme Court enumerated five specific factors which

would justify the delay of desegregation in a community,

and the delay of effective desegregation of the vocational

and technical training which would result in this plan is not

founded upon any of the enumerated reasons set out by

the Supreme Court.

The defendants reply to this objection by saying, first,

there is no limiting factor; second, the Supreme Court’s

mention of these factors justifying delay was merely illus

trative and not conclusive.

Paragraph five states that in the continued promotion

of the vocational program in the Knoxville City Schools,

the Board of Education will follow the rules and regula

tions as set forth by the State Board for Vocational Educa

tion.

Opinion Dated June 19,1961

42a

Plaintiffs object to this paragraph upon the ground that

negro children above the first grade are forever denied

desegregation by the plan. Defendants’ answer to this

objection is that the plan provides complete desegregation

with respect to all qualified students and the reference to

the children in the first grade and above is meaningless

and irrelevant.

Paragraph six provides that the principals of schools

involved, the director of vocational education, and the

superintendent acting on behalf of the Board of Education,

will be responsible for carrying out this plan consistent

with sound school administration and without regard to

race.

Plaintiffs’ objection to this paragraph is the same as

objection number five, except they specifically make ob

jection number six for themselves and all other negroes

similarly situated. Defendants say that the objection is

irrelevant for the purpose of this hearing.

Paragraph seven provides that this plan shall become

effective at the beginning of the school year, September

1961.

Plaintiffs object to the enforcement or effectiveness in

respect to vocational and technical training of the provi

sions of paragraph six of the general step-by-step plan of

desegregation heretofore under examination by the Court,

paragraph six being the paragraph in which certain

grounds for transfer were referred to. In the original

hearing, plaintiffs took the position that paragraph, six

was illegal and defective.

Defendants, in response to this objection, say: First,

that this Court has held paragraph six of the general plan

valid; second, since Fulton and Austin are not schools of

district-wide jurisdiction, but are schools whose areas ex

Opinion Dated June 19,1961

43a

tend to the limits of the City boundary lines, and either

may admit students from any section of the City, the pro

visions of paragraph six of the general plan may not be

pertinent to any transfer problem under the vocational and

technical plan.

Plaintiffs also object to the plan upon the ground that

the standards are vague with respect to how a student is

to be regarded as a qualified applicant for technical train

ing, and that this vagueness may result in racial discrimi

nation. Defendants answer this objection by asserting

that the standards are not vague, and even if they were,

discrimination on the ground of race is expressly forbidden

and that it must be presumed that the school authorities

will enforce their plan in a legal manner.

The final objection made by plaintiffs to the plan is that

the transfer provisions which are incorporated in the Ful

ton plan have not previously applied to vocational and

technical students at either Fulton or Austin High Schools

but will apply to negro children in the future. Defendants

answer that contention by saying that the transfer provi

sions will not only apply to negro children in the future but

equally well to white children.

The Court has heard Superintendent Johnston testify

today with respect to the merits of the plan. Mr. Johnston

stated that there were 500 vocational students in Fulton

High Schools last year with about 15 vocational teachers;

that there were 355 vocational students at Austin High

School with about 10 teachers. Nine vocational courses

offered at Austin High School and 15 vocational courses

offered at Fulton; Austin offering courses that Fulton did

not offer, and Fulton offering courses that Austin did not

offer.

Under the present plan, all courses that are offered at

Austin will likewise be offered at Fulton, but if Fulton

Opinion Dated June 19,1961

4.4a

fails to offer any course that is offered at Austin, white

children may attend these courses at Austin. Likewise, if

Fulton offers courses that are not offered at Austin, negro

children may attend Fulton in order that such courses

may be available to them.

Mr. Johnston stated, in substance, that all of the chil

dren in Knoxville will be treated alike with respect to

vocational courses, or, to put it in another way, no child

because of color will be deprived of an opportunity to get

a high school vocational education in the Knoxville schools.

The Court is of the opinion that the Board has made a

good faith effort to comply with the Court’s directions

contained in its memorandum dated August 19, 1960 and

heretofore mentioned.

The Court is further of the opinion that the supple

mental plan is a feasible plan and meets Constitutional

requirements with possibly one exception, which may be

illustrated in this manner. A student who lives near Ful

ton and who possesses the necessary vocational qualifica

tions to enter Fulton should not be required to travel

across town to attend Austin when Fulton is much nearer.

The Court, in this proceeding, on its own motion, ques

tioned counsel for the defendants and counsel frankly

stated that he could see no reason why the colored student

in that situation should not be permitted to take vocational

courses in Fulton.

The Court recognizes the principle in law that it should

not substitute its judgment for the.judgment of the Board

of Education unless necessary to enforce Constitutional

rights. The operation of these schools addresses itself

primarily to the Board of Education.

The Board of Education is charged with the respon

sibility of operating Fulton and Austin high schools, and

Opinion Dated June 19,1961

45a

this Court will not interfere except where necessary to

protect Constitutional rights.

As previously indicated, the Court is of the opinion that

the Board has made a good faith effort to submit a supple

mental plan that meets the requirements of the Constitu

tion and that deals justly with the school children of Knox

ville, and with the sole reservation heretofore indicated

the Court approves the plan as submitted.

In this connection, the Court requests the Superintendent

and the Board of Education to restudy this one phase of

the problem and try to present a plan that will meet the

difficulty, if it is a real difficulty, which the Court has

tried to point out by the foregoing illustration.